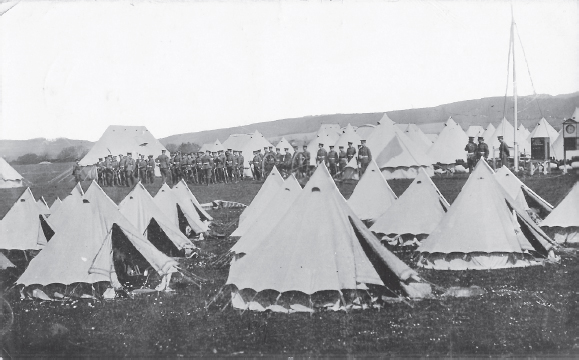

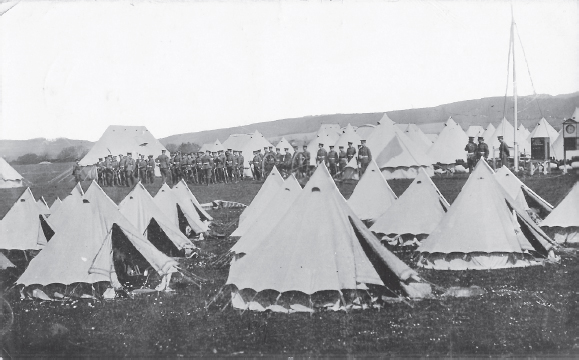

St Martin’s Plain, Shorncliffe Camp

St Martin’s Plain, Shorncliffe Camp

THE SPRING OF 1915, one of the bloodiest periods on the Western Front, was followed during the balance of the year without a major battle involving the Canadians.

OUR YOUNG SOLDIERS LOOKED FORWARD to their summer rest periods: they called them “glorious picnics,” which were often quite exciting. They built huts and tents. André, with his friend Stewart, built a very comfortable shelter. They swam in the Lys, a small lazy river that wasn’t bothered by the war and continued to flow peacefully towards the Escaut, and they played games in the fields, now dried by the good weather.—(BB)

9 August 1915

My dear mother,

I want first of all to reassure you about our security. Here we are in the trenches, but everything is so quiet that one feels almost at home. In fact, everything is organized for the best. I think that you can also count on us not to expose ourselves unnecessarily to a bombardment, but even in a relatively quiet Front there can be accidents. You will have heard about the death of Bill Lester. It was a terrible shock for all of us, as he was one of the most loved in the company, always so jovial, and in good humour, and he is up until now the only one who has received even a scratch. But I think that, if I were to die, like him, I would be ready. I am counting on the Lord’s pardon.

You will be happy to know that André and I are together, and both of us perfectly well. We do our little cooking with Bruneau and Stewart and with the addition of what we have bought in town before leaving, and a few surprises from Tante Julia, we are coping very well.

Etienne

10 August 1915

Dear Jacques,

We are thinking of you during your birthday, while hearing the “Wisbangs” whistling over our heads.

It’s not something that one likes to tell his mother, but we are a little flearidden, which is not very pleasant for those not used to it. We wash in water, which is not of a quality even equal to the contents of the pail under the kitchen sink, but what can you do, that’s life in the trenches! It’s quite funny to be there after having heard so much about it.

André

PPCLI A.10963 19 August 1915

My dear mother,

We have had a lot of rain these last few days, and we naturally enjoy the inevitable mud in our sleeping holes. However, since we don’t sleep very often nor for very long, having had only two hours of rest last night, and the two hours weren’t all in a row, you can imagine that I was in a great mood, while cooking our breakfast with wet wood and kneeling in the mud!

We are completing our period in the saphead, a kind of passageway leading towards the German trenches. The other night when I was on guard, I almost thought that I was at 16 Island Lake, as the machine guns looked so much like speedboats. The German machine guns are absolutely like Millette’s speedboat, while the British ones look like an old two-cylinder motorboat.

If you think that you are the only ones who eat well, you are completely wrong. How would you like a good dish of potatoes, cooked in bacon grease and topped up with cheese, or an excellent dish of roast potatoes cooked in bacon and sprinkled with tomatoes?

André

My dear mother,

Here is André returning from the rear. He hadn’t been feeling well, and the doctor sent him there for two days. He’s come back with a flourishing expression, on foot, with a bag on his back and gun on his shoulder, saying that he had enjoyed a little rest in a nearby village schoolroom, surrounded by a nice garden and a few trips in a motorized ambulance to distract him. Let’s hope he doesn’t have to go to a hospital for something more serious.

Like the last time, André and I are in an advanced position, a “sap,” which is about sixty metres ahead of the first-line trenches. We get a little less sleep than in the other positions. With twelve men and a corporal, we need to furnish two guards all night long for three positions, but on the other hand we have more time to rest during the day. While the others spend a good part of the day digging and filling sand bags, all we have to do is deliver these two guards, while the others read, write, cook, and sleep. Sydney Bruneau, André, and I have adopted the system of two meals a day at about 10 a.m. and 5 p.m. We prefer to have a good sleep from sunrise to about 9 o’clock. That’s when one of us gets up to prepare the 10 a.m. meal. The first problem is water. We need to walk ten minutes zigzagging in the trenches right up to the yard of a ruined farm to procure the precious liquid. In addition, it looked as though the Germans would cut our water supply for good when one day we saw that they had located a machine gun there to protect it. Fortunately, they moved on, so we can once again go there to get the water for our coffee and cocoa. The chef’s second problem is to find wood. Our rations are received raw, and all that we get to cook them is coke that doesn’t burn in an open fire. We have to steal what we can, maybe a box, or a board, or a fence post. In the evening, the same process to prepare the dinner. The rations consist of bacon, bread, cheese, jam, tea, sugar, and from time to time condensed milk, butter, or tinned stew. I’m not counting the boxes of meat from Chicago, the “bully beef” that no one eats if he can find something else.

The morning and evening meals are interrupted by two inspections that we could well do without. In the morning it’s the sanitary service, “Corporal Chloride” as we call him. He passes with a pail of chloride that he spreads amply on the floor of the trenches and the dugouts, and is furious with a red face when he sees uncovered food or dirty plates. The poor guy, I think we frustrate him. In the evening, it’s the inspection of the rifles. An officer comes along with the sergeant major and a sergeant. Each rifle must shine both inside and out, and horrors for someone whose rifle is not absolutely clean, even if it’s one speck of dust.

Etienne

My dear father,

Our battalion has left the trenches and here we are once again all reunited at the rest camp where we had rejoined our regiment six weeks ago. In our absence they have built many new tents, which means that we can all be sheltered, as well as the 2nd University Company, who have joined us here.

Yesterday afternoon, André and I and two others got a leave to go to the nearby village. As we went by the old Gothic church, the sound of the organ attracted us, and we sat and listened for a few minutes to the old Highlander playing the organ. Afterwards, I continued alone right up to the next town. The town is almost abandoned by the civilians as a result of the bombardment, but I think that the absent are more than replaced by the British soldiers.

I have just heard that my name was mentioned in Shorncliffe’s promotion announcements.

Etienne

6 September 1915

My dear parents,

Briefly, our battalion spent the month in trenches quite close to Armentières, in an especially secure section of the Front. The Germans are more than three hundred metres from our trenches at this place, and don’t seem to want to do anything much. After a fifteen-day rest, the Patricias have to enter other trenches nearby. I don’t think that they will be more dangerous or more uncomfortable than the last ones. Since the arrival of the 2nd Company the regiment has been reorganized. André is in the 2nd platoon of the 2nd Company. His lieutenant is M. Trevin, who we have had since the beginning, and his sergeant McClean, who you will have seen at the departure in Montreal. McClean is a much-loved sergeant. He is firm and soft, a combination that you don’t often find. Unfortunately, the reorganization has divided our section. They have put some new men and some veterans in the four sections of the platoon. However André is still in the same section as Stewart, and is never very far from his former friends of the old Section 5.

Etienne

7 September 1915

My dear mother,

We are still the two of us together, and nothing indicates that we are to be separated soon. You seem to think, dear mother, that it’s only at La Clairière that one can have beautiful quiet evenings, but one couldn’t imagine a countryside as charming as this old farm in the midst of the wheat fields, where the golden bunches are waiting to be picked, and with these tall poplars along the side of the roads that zigzag through this fertile plain. Only the sound of an airplane circling overhead and the spanking new reserve trench, which hopefully will never be used, reminds us that we are fighting a war.

Etienne

ONE MORNING, Etienne and three mates are called by the warrant officer. The command is to leave immediately for an officer training school in England. Mostly good news, but it isn’t without some regret that the two brothers leave in different directions from the small train station in Steenwerck. Being together was like being at home away from home!

The officer school is in Shorncliffe, and everything seemed quite charming to a private coming from the trenches: a dry and stylish uniform rather than the wet khaki, a ceremonial mess replacing a dirty shelter, clean, comfortable beds after the mud and the vermin over there, intellectual stimulation instead of passive obedience. It was new, stimulating, and was to last five months that went by quickly, as the days were full with the theory, the exercises, the equitation, then, during the breaks, with sports and walks in the lovely English countryside in all its autumn glory. There were also the charming visits to the Penrose-Fitzgerald cousins in Folkestone, and some interesting weekends in London. The clubs, the theatres, the friends, the welcome at the Swiss church, all of it attracted Etienne.—(BB)

Folkestone, 8 September 1915

My dear father,

I can’t believe my eyes, but here I am in a hotel room in Folkestone, instead of waking up in my tent corner near Armentières. You will have learned from the telegram that I sent you that I have finally gotten this famous promotion, but it seems as though it’s not in the artillery. I need to meet this morning with the colonel.

Yesterday morning at 9:30 we were all lined up in the camp’s exercise field for the inspection of our equipment when the sergeant major called my name and asked me to see the adjutant. There, I met three others who had been called in the same way. He tells us that he has the order to send us immediately to England to receive our promotion.

André accompanied me right up to the Steenwerck station.

Etienne

10 September 1915

My dear mother,

I have a nice little room in one of the huts reserved for officers. It has a galvanized tin roof, quite nice furniture, and varnished white wood walls. I have a batman to shine my shoes, do my room, prepare my morning bath, etc. You can imagine, my dear mother, how funny this seems to me.

At 6:30 p.m. the bugle blows for dinner. It is a fairly formal gathering: the officers are placed in order of rank around a big table of a T-shape and sit when the colonel has said grace. The meal is very good and well served, but beware about arriving late, as one has to excuse oneself to the colonel. After dessert there is always a toast to the king, made by the colonel.

Thursday morning, my friend H.S. and I went to London, with only a three-day leave to order our uniforms and all that we need. The government is generous for that, but it seems to me that it’s the tailors and the stores who profit the most. We receive £50 for our equipment. That seems to be a lot of money when one needs to spend £1 for a cap, and £4 for a tunic.

As I left the Paymaster’s office and walked down Whitehall, I saw a familiar face, and sure enough it was Sergeant H. Mathewson, who had just come from Shorncliffe for a few days in London. He is one of those that joined the so-called Mounted Rifles, an infantry regiment who are currently in Shorncliffe.

Etienne

17 September 1915

My dear father,

I’ll try to send you one or two photographs of our huts. There are four huts for sleeping, divided into little rooms of about thirteen feet by nine, and a larger hut for the mess and the kitchen. They are set in a half-circle on the edge of a plateau covered with soldiers’ huts and overlooking the sea. Wednesday afternoon I went to have tea at the Fitzgeralds’, who were surprised to see me back so soon from the Front. While I have time I will go and see a few of my friends in the nearby camps. The Montreal Rifles, with Paul Black and Nicholson, are very close to here. Jean also asks me to see Arthur Mathewson at the Highlanders, who are in the same section of Shorncliffe as us.

Etienne

BLANCHE’S FIRST COUSIN had married Admiral Charles Fitzgerald, and they lived in Folkestone, a few miles from the Shorncliffe Camp. Etienne developed a close relationship with them during his long visits to Shorncliffe.

Admiral Charles Fitzgerald was for many years second-in-command of the Admiralty’s China Station. He is best known for the controversy that arose following a poorly translated version of an article he wrote for the Deutsche Review. The Germans interpreted it as saying that Britain would be better served by a war sooner rather than later, when the German navy would be larger. Partly in order to regain his image in Britain, he organized a group of women in Folkestone to distribute white feathers to men not in uniform. It was reported in the press and rapidly spread across the country.

26 September 1915

My dear mother,

I am very lucky to be able to take this course that is both complete and interesting, but I think that at the end of the three months I will have had enough of this easy life here, and that I will look forward to going back to the Front and to doing something useful as soon as possible. I wonder when my turn will come up. There are so many officers ahead of me on the list that something would need to happen if my turn was ever to materialize.

Etienne

15 October 1915

Dear Philippe,

André wrote about how the French took the German prisoners and replaced them with men from his battalion in the trenches and how they were bombarded by German shells of poor quality that for the most part didn’t explode.

My day starts at 6:15 a.m. when my batman comes to wake me. He also takes my shoes to shine them and my belt to burnish it. At 9 we must be on our horses and lined up in front of the stables of the cavalry school. During an hour and a half we do equitation exercises. We have then two courses until 12:30. The afternoon courses are from 2 to 5:30, and from time to time a course of topography in the field.

On Sunday I attended a service at the small Anglican church. The clergyman was an amusing old man who told us quietly that he would read us the sermon he had prepared eleven years ago!

Etienne

20 October 1915

My dear Philippe,

Saturday afternoon, Robertson, one of the officers in our battalion, and I had the good idea to ride for more than three hours, right up to the Otter Pool camp, about five miles from here, and had tea in a well-kept little inn on the side of the road. Robertson, who was leading, wearing a raincoat, looked like a major or a colonel, followed by a lieutenant carrying an order. In any case that’s how we interpreted the salute that we received from the officers that we passed.

Etienne

25 October 1915

My dear mother,

You ask if I have some good friends? ... Yes, certainly. I see mostly the ten that are at the military school with me. They may not all have the same ideas as me, but there are many great guys amongst them, and I have good relations with everyone.

You then tell me that, according to Mr Roussel, one finds in France that the English officers could have a more complete and more scientific preparation. That’s absolutely true and quite inevitable in a completely new army. But, since we have the opportunity to spend a little time to prepare, it’s up to us to make sure that we don’t merit this reproach.

I’m sure that you will be happy to receive these few letters received in Jean’s last letter. It’s curious that a French officer had the right to give such complete details of the operation of his battery as described in Cousin Emile’s letter.

As reported by various people who have come back from the trenches, I hear that André is now in the rear, at a rest camp about twelve miles behind the lines. The regiment certainly deserves a little rest after three weeks in the trenches.

Etienne

31 October 1915

My dear father,

Yesterday we had to stay inside and waste the greater part of the day. But Thursday and Friday of last week, we were building bridges across the Hythe Canal, like those built by the English at the time of Napoleon’s projected invasion, where he could have easily landed on a dry lowland. First of all we built two sections of a bridge of about the same style as Caesar’s bridge across the Rhine, and then a gangway for the pedestrians, lying on barrels. It’s an interesting job, but I don’t think that we would ever have to build such bridges at the Front.

Etienne

AT THE BEGINNING OF THE AUTUMN, when Etienne left for England, it seemed as though there was adversity in all directions. In the trenches, during the endless bombardments, the soldiers began living like cavemen. There were vermin attacks, continuous rain that soaked them from head to foot, and greasy sticky mud from the waist down. Night-time brought little relief, with only a wet blanket to protect them from the cold and damp environment. The sunny carefree days were few and far between. We guess about all this in reading between the lines of André’s letters. However, he doesn’t exaggerate the dangers and deprivations, trying on the contrary to show the acceptable sides of the situation.—(BB)

10 September 1915

My dear parents,

I have just received your good letter of 21 August that made me very happy, especially as a replacement for the sudden departure of my secretary, Etienne, who was suddenly called back to England. This was very sad for me, but I was expecting it.

We are finishing our rest camp, and will go back to the trenches next week. We each received a blanket the other day, which I can assure you wasn’t too much, as we have had to continually get up and run in the fields to warm up.

Mother sends some lovely descriptions of your sitting room, which must be very pleasant and comfortable, but that doesn’t approach the standards in our small huts. It is true that one can’t stand up in them, and that there are more holes than canvas at both ends, but in the evening we aren’t so badly off, lying on the hard ground or, when it’s raining, in the mud, with a candle on the lunch box to read, or one of the veterans telling us stories about his various wars. We also discuss this war, which isn’t always very pleasant, except today where we have had rumours about victory in Russia.

The local villagers are very amusing with their strange accents and expressions, some blacks from Africa, and the usual French and English, many of whom are talented singers. The old Negro ballads from their ancient wars are great.

André

BACK AT THE HOSPITAL, Jean is busy in the registrar’s office …

Army Post Office S/L BEF France 27 October 1915

My dear mother

Half our wards are closed, as we needed the workers outside to prepare for winter, and in any case the ones that are still open are not close to being full. Last Friday we received two hundred wounded and sick, and since then, none.

Wake-up time here is at 6 a.m., and I usually head for my office at 7:30, where I await the arrival of my captain. I currently spend the day at the Corps Office, where I’m involved in a multitude of tasks. You will have seen that, according to the correspondent of the Star, what annoys Colonel Birkett, the commanding officer of the hospital, the most is the huge quantity of French administrative paperwork. For example, every Saturday we need to send five lists of the Corps’s officers with their different qualifications. We work until 6 p.m., and twice a week I am on duty in the evening. In addition, obviously, we need to work at night when the ambulance trains arrive, etc.

I have, naturally, less opportunity to see the wounded than those that work in the hospital. I have often talked to them when I saw them in the camp. Most of them like to talk about their exploits at the Front, but they rarely talk about what they did themselves. There haven’t been any attacks for some time, so almost half the men that are sent to us are sick and not wounded.

The staff at the administration hut. Colonel Birkett (centre) and Jean (second from left at the rear)

The administration hut

I’m very sad not to be able to send you photos of our camp, but as I think I already told you, all those who were found to have cameras after our arrival in France were punished and had their cameras confiscated.

We will here on in only be given one leave per week. That’s too bad, because I very much enjoyed the opportunity to visit the area.

I have just torn the little wreath that you have sent me. I don’t know any of these young people nor the Miss? They don’t interest me a lot. I don’t collect photographs of young girls that I know and even less of young girls that I only know by name.

Jean

IN OCTOBER 1915, the Princess Pats, were sad to leave the Armentières region, where they had enjoyed several pleasant months in the company of the local residents. From there they took the train to a small town in the Somme valley called Guillancourt.

AT THE BEGINNING OF OCTOBER, the long column advances towards the Somme. The weather is beautiful and cold. André, with his friends, Malcolm Stewart, Jim Mosley, Bill Calder, and Sydney Bruneau, make some important archaeological excavations in the ruins of a village. They discover a stove, some bed frames, and some excellent wool mattresses in the ruins of a bombarded house. Their shelter becomes very comfortable! Bruneau even finds many pictures and interesting books in a collapsed farmhouse. To what rustic intellectual would they have belonged? André meanwhile chooses an oak plate in the ruins of a chapel … Then, sitting on the bank of a canal, with only his penknife and his agile hands, he sculpts for us the crest of the Princess Pats, almost perfect in every detail. This first present from the Front was a sensation in Westmount.—(BB)

FROM GUILLANCOURT the Patricias marched along the banks of the Somme Canal to a hut bivouac near Bray, where the British Third Army was headquartered. They then went into front-line trenches lying south of the River near Frise, with supports at Eclusier-Vaux and reserves at the village of Cappy. The trenches were excellent, as the marl sub-soil of Picardy was ideal for the construction of trenches and other fortified earthworks. It was a particularly pleasant stay, without otherwise anything special to report.

L’Eclusier Somme, 23 September 1915

My dear mother,

We have travelled a great deal this week and we are located in a very beautiful part of France, a countryside that is much more mountainous than Flanders. You asked me about the meals. In the trenches we cook the meals ourselves, with bacon, cheese, corned beef, and potatoes sometimes, and what we bring ourselves: Quaker Oats, chocolate, condensed milk, and dried fruit. But when we aren’t in the trenches we are in reserve, and there the chefs cook the meals in their mobile kitchens.

I’m pleased to say that I have some good friends that are replacing Etienne.

André

2 October 1915

My dear parents,

We are very happy when at dawn we can go into our dugouts, light our little stove (found on a lot where there had been a house, in a big village that we occupy), and make some tea, and our meal, before having a sleep on the pile of straw at the bottom of the trench, almost until lunch, or in one of the dugouts where we have installed some real beds with springs and very comfortable wool mattresses that we found in a nearby ruin.

Before entering these trenches we lived in a village with only three inhabitants, an old couple of about ninety years of age and a young girl who received the Legion of Honour and the Military Medal for having opened the dam and flooded the Germans when they were here.

Last night the Germans set fire to some hay bales with their shells, and it was magnificent to see them burn, with the steeple of an old church illuminated in the distance.

We rarely shoot, and the Germans even less, and it’s very quiet, other than for the artillery duels. I am annoyed at not being able to give you a more complete breakdown of our day, but during the day we have about four hours of sentry duty and one at night, with hours of rest, until the morning.

During the day, between sentry duties, we need to dig trenches and do various other jobs.

At around four o’clock in the morning we receive our rations for the day: a piece of bacon, a piece of frozen meat, a half a pound of bread, a little jam, and some cigarettes.

André

5 October 1915

Dear Etienne,

Our trenches aren’t too bad, and we have a few very big dugouts, with a stove in almost all of them. There are even some with doors and windows, all of that picked up from the village right behind us; all the wonderful bed springs are obviously used.

We have been bombarded this morning with about ten shells, and about half didn’t explode, which shows the quality of the German munitions. We have a super Captain. He’s very active and intelligent, and a very good sniper. He has already killed a German with a new rifle with a periscope that he brought with him. I understand that we are now going to do longer trench periods, of about fifteen days. I’m quite pleased, as this will result in less marching, and the opportunity to improve our set-up.

You haven’t yet told us what battalions were in Shorncliffe, or where you will probably be transferred? Don’t forget to tell your riding instructor that you have a lot of riding experience, since you rode a pony in Dorset! I envy your position a little, but as you seem to envy mine, we should be satisfied where we are. Tell me your thoughts about the advances on the Western Front, and whether this will affect the end of the war. I don’t know if I told you that when we arrived in this district I saw my first Germans. They weren’t very dangerous, as they were prisoners of the French that we were replacing. These poor guys looked as though they had had enough of the war, especially one seventeen or eighteen years old that had a pretty depressed expression.

André

7 October 1915

My dear mother,

You ask me to describe one of my days. There are so many different types that it’s difficult to say. On some days, when we have worked all night, we don’t do anything the next day. Other times they ask us to do drill and parades for hours. Finally, from time to time we try to finish the war!

André

15 October 1915

My dear family,

When I’m on guard duty during the day, and I look through the periscope (that has about the same dimensions as a photo), I see the two lines of the Germans cut out of the chalk. In the foreground is our barbed-wire fence, about ten yards wide, which looks impenetrable. All this accompanied by the thunder of the terrible bombardment of Arras. And then I glance for a couple of minutes at these wonderful photographs of La Clairière, especially the one of the dining room with its cups, tablecloths, and the comforting smile of all those faces, and that makes me feel good. Meanwhile, I tell myself that the quicker we cut the Kaiser’s, and little Willy’s, heads off, and stopped this terrible destruction, the better it will be.

Here’s my usual day: between 5:30 and 6 we receive our rations for the day. The rations include meat, bread, jam, sometimes butter, cheese, tea, sugar, and a half-inch candle per week. As soon as we receive the rations, we have our breakfast: bacon, tea, bread, jam, and a little something extra from our parcel. After breakfast, which finishes at about eight, we sleep for two or three hours. From the moment we get up right up to supper, at about 3:30, there’s lots to do, including fetching water and wood. The water is quite close, from a pump in a beautiful ruined farm, and the farmer wasn’t just anybody, judging by his library. Bruneau had even found a number of books that would have had considerable value at McGill. In a pile of rubble I found a lovely collection of prints of Rome and its ruins. With regard to the wood, the best I could find I ripped off the old Gothic pulpit in the church. There were some beautiful pieces of oak, engraved and sculpted. Having done all that, a quick wash is required. We take what the British call a sunbath; I don’t know if the British sector has an influence here. As well as the bath, soldiers can be seen sitting in the sun, doing a very thorough inspection of their shirts. I don’t want to go on and on with these details, but it is a fact that this process takes about an hour and that the victims add up to over fifty. For supper, we prepare a meat-and-potato stew, accompanied by chocolate and cake given by you. Following the washing up and the cleaning of the dugout, it’s 5:30, and the twelve hours of night work begin. I am usually able to sleep uninterrupted for three hours. The rest of the time we search in the darkness of no man’s land, to make sure that the Germans don’t take us by surprise.

The other day it was dark at around six o’clock, and all of a sudden we got the order to put on our gas masks. You should have seen how fast the order was executed. Everyone climbs up on the shooting platform with his bayonets clipped on. We even started to shoot towards the German trenches, until we were told that it was a false alarm. We had felt sure that the Germans were about to attack.

We were bombarded a little the other day, and a few people were wounded. The Germans attempted revenge, after three of our bombers trapped one of their squads as they marched four-by-four ... all those that could, scattered.

André

1 November 1915

My dear mother,

The other day McKeeken, the one that was in the Niagara group, and I, went to visit the town, the first one that I have visited since Boulogne that isn’t a ruin, or about to be one. We left after lunch through some beautiful, very French, woods, with all the branches and logs neatly piled, and the little woodcutters huts were like the ones near Paris. Two hours across woods, fields, and roads brought us to the end of the line of the electric tram, with drivers who either had white beards or were fourteen or fifteen years old. Twenty minutes zigzagging along small, winding streets, and through some lovely modern squares, brought us to what I believe is the most beautiful thing I have ever seen in my life: the Amiens Cathedral. It was too bad that all of the base was encased in sandbags as a protection from the German bombs, but fortunately they weren’t piled high enough to cover the saints lined up about halfway up, and the incredible mosaic, which is reputed to be the most beautiful in the world. The interior was even better than the exterior, and it was the great height that impressed me the most. After another visit in town, we went to a restaurant and sat down at a table with plates, knives, forks, and the whole works; it was the first time that I had eaten at a table in four months. I think that I did all right, and I’m not ashamed to say that we ate everything that there was on the menu, right to the last crumb.

André

THE PRINCESS PATS LEFT THE SWAMPS of the Somme and marched westwards through Amiens to Flexicourt. They remained there for several weeks, where they taught fresh British recruits that had been sent to reinforce the Third Army.

IN THE ARMY ONE KEEPS MOVING. In Anglo-Black slang it was: “always walking.” Soldiers ignore the passing of time as they move from Flanders to the Somme, from the Somme to Artois or to Picardy, only knowing that somewhere there’s a need for their bodies as a shield, or for their courage as a tank. Sometimes, at the end of the road it is hell, and sometimes a rather pleasant stop, like at Flexicourt, where the company had the good fortune to stay in a ballroom, behind closed doors, gaily decorated by the village artist, and with the opportunity to tinkle on one of the three pianos and play billiards. Except when they were training Kitchener’s new army.—(BB)

9 November 1915

Dear Etienne,

I don’t know if I told you that my friend Stewart and I are in the machinegun section. We are given several training sessions per week, and the work is very interesting.

Since I wrote to you last, we have moved again. We are now in a big village where they manufacture canvas. We are here as a teaching battalion for some new battalions of Kitchener’s army.

I wish that you could come and visit our lodging! It’s not an old barn surrounded by rocks, with almost no walls. It is a first-class café, and we are housed in the ballroom. There are two or three pianos and a very colourful decor done by the village painter! We have taken advantage of the situation to have a concert this evening, and I must rush to finish, as it will soon start.

André

Flexicourt, 21 November 1915

Dear Philippe,

I congratulate you for having played on your class team; you must have had a very good time. We have a corporal in our platoon who played for the Hamilton Tigers last year, and he was telling me the other day that he was more interested in reading about Canadian football than any war stories in any of the world papers.

We are here as battalion instructors for one of Kitchener’s new army’s NCO schools. We have lots of ceremonies and parades with our flag unfurled, three sergeants and one lieutenant to guard it. I was on guard duty the other day, and I can tell you that it wasn’t warm between midnight and 2 a.m., with snow on the ground since last week.

André

TOWARDS THE END OF 1915, there were some modifications within the structure of the military organization in the Western Front. General Joffre remained the supreme commander of the French forces, and Lt General Douglas Haig was named Commander-in-Chief of the British Army, replacing General Sir John French. The Canadian Expeditionary Force was created, with Lt General Anderson as Commanding Officer. The fast-rising Major General Arthur Currie was promoted to Commanding Officer of the 1st Canadian Division, and, on 27 November, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was merged with the 7th Brigade, under the helm of the 3rd Canadian Division.

Christmas 1915 was quiet, prior to their move to the Front at Kemmel, at the south end of the Ypres Salient.

ANDRÉ WAS SENT TO ROUEN and Harfleur for several weeks, on sick leave.—(BB)

26 November 1915

My dear mother,

Here I am in the hospital for a few days, with some pains in my back. With the application of hot compresses, they are now almost cured. About twenty-five of us are lodged in a big tent, with a coal-burning stove and electric lights. We don’t do much all day long. We sit around the stove to read and chat; there is with us a funny old English tramp, who tells us about his adventures on the road and in jail!

André

11 December 1915

My dear parents,

Address my letters here, as I will be at the convalescent camp for a while before returning to the regiment. I thank Dad a lot for his letter and for his word of introduction to the wife of the Amiens pastor, but the letter unfortunately arrived too late, because there are several other towns with cathedrals in France, in addition to Amiens.

I am sending you a little present of no great value.

André

25 December 1915

My dear mother,

I was released from the hospital, as I was almost completely recovered from my problem. I arrived at the convalescent camp in the evening and the next day, after an inspection by the doctor, they told me to leave that evening for Le Havre, which is our base.

We sleep in round tents that aren’t at all what could be called waterproof. It might interest you to know how I spent my Christmas. As one of the old boys, I was free for the rest of the day. We had an excellent lunch, served by the sergeants: ham and potatoes, turkey with pudding, roast beef, cake, and candies. At dessert, the colonel entered with a bunch of officers, and drank to our health.

André

Canadian Base Depot Le Havre, 10 January 1916

My dear mother,

Life is quite monotonous here: we get up at five or six, depending on the days, and the days are spent sometimes in repairing the roads or other jobs in the training camp. It seems quite peculiar to be walking in a French town; everything is so different! If Canada wasn’t so far away, I would love to send you a little bit of that wonderful French pastry that I tasted in one of these “patisseries.”

André

BEF France, 24 January 1916

My dear mother,

Here I am, as you can see from my address, back with my battalion. Despite the fact that there is more mud and other minor inconveniences, I am glad to be back and to find my friends.

André

4 February 1916

My dear mother,

My comrades did finally get their parcels, as well as mine. In that I wasn’t there, rather than sending it back, they consumed it. I am quite well, although I have a cold, but I’m not the only one: the lack of heating is of not much help.

You talk about my long period of inactivity. I don’t really know what that’s like since my arrival in France. Don’t talk to me about a diet, that’s of no interest, and in any case it isn’t useful. I can assure you that no one presents me with a menu before each meal.

André

22 November 1915

My dear mother,

You can imagine my surprise, and obviously my joy, when the director of the military school, during the Saturday-morning exams, hands me a typewritten note that I need to sign. It’s an order for my departure to France, Wednesday next week, for fifteen days of on-site instruction. I couldn’t imagine what brought me this unexpected opportunity. Twentyone of us out of a class of fifty are going. It’s strange that they chose me, who has already been to the Front. In any case, don’t worry. Things have been very calm these days, and in fact I don’t think I’ll be in the trenches for long. I’ll probably already be back here when you receive this letter. I hope to be able to see Jean, but I don’t dare hope to go and do a tour as far as the Princess Patricias.

Etienne

29 November 1915

My dear father,

I’m writing to you from my dugout somewhere along the firing line. It’s about the only place where one can escape from this terrible mud. I don’t have time to send a long letter today, as I’m quite busy here. I’m at the Canadian 27th Battalion for a few days. At our arrival near the firing line, Fife and I were sent to this battalion. We were first of all invited for supper by the quartermaster, who fed us and found us a bed. Then we left the next morning for the trenches, he in one company and me in another. I was well-received by the captain and the officers of my company. It’s a pleasure to work with them. The first night I didn’t have much to do other than to have a good sleep, but last night, I was up all night. I was asked, with a sergeant, to do the rounds of the guards, at regular intervals, and to make sure everything was going well. It seemed to me at first to be rather incredible to be alone in charge of the whole trench, but it went much better than I had imagined.

I was telling you that the mud was terrible. I think that someone who hasn’t seen the trenches during a rainy day could not imagine the reality. It’s only by wearing a huge pair of leather boots of over a foot above the knee that one can risk it. But the mud is not the only problem during this rainy weather. The rain soaks the trench walls, which collapse into the trenches, and the men are rebuilding them from morning till night. However, according to the letters that I censored last night, they don’t seem to be complaining at all, taking all the little problems in their stride.

N.B. It’s nonsense to remind you at the end of a letter like this one, but now that I think about it, I could get into some serious trouble if ever you allowed the publication of any part of this letter.

Etienne

10 December 1915

My dear mother,

I can at last settle a little bit more comfortably to write a letter. We are now in some huts a few miles behind the lines. The six officers of our company have a big hut with a good fire, bunks that are a little hard, but dry, where we don’t have the company, more or less desirable, of rats and mice (the rats and mice have found a way to share the leather buttons of my vest while I was in the trenches). It was during some awful weather that we left the trenches. The battalion that was taking our place arrived only one hour after nightfall. Once they were settled in, we zigzagged along the communication trench. Despite having worked all week on the draining, we had water right up to our calves. After the trench, a muddy road, then the big paving stones of the Belgian roads. Finally, after maybe a two-and-a-half-hour walk, we arrived here. Fortunately, one of our officers was here in advance to see to it that the company found a good fire and straw on the bunks on arrival.

This morning it is the same wet weather as yesterday, with a fine rain that makes you appreciate the spot next to the fire. Most of the men went down to the nearby village to take a bath. I hope to do the same this afternoon, but it’s not always easy to get permission to leave one’s lodging, as the battalion can be called at any time. While we are here, we will have to take the men a little bit in every direction to do all sorts of work in the trenches. The mud, the water, as well as the German shells destroy everything, and one has to continuously rebuild and repair, as well as starting new projects.

I hope to see André. He mustn’t be very far from here. I haven’t had any news from him for quite a long time. I hope that he has completely recovered. The letter from Jean told me that he hadn’t been well.

Etienne

19 December 1915

My dear mother,

It seems that Philippe also wants to leave, to join us here. I can only tell him that I would be very happy to be in his place, sitting by the fire at Les Colombettes. Is it his friend Gordon Nicholson who enrolled in the 5th University Company?

It was Thursday morning that I left the Front, a little sad to leave this regiment where I had made some good friends. We got on the bus that was to take us to Boulogne, taking with us pieces of shells, German barbed wire, etc., souvenirs to send from England to our parents and the friends of a few officers. They even wanted to load us with a German drum that fortunately wasn’t wrapped at the time of our departure.

On my arrival in Boulogne at 5 p.m., I dash over to the hospital to inquire about Jean. A disappointing result: he’s still at Dannes-Camiers. I have two friends who were transferred to the artillery, and I think that the colonel of the reserve brigade would admit me also. I would much prefer to be in the artillery, and I think that I would be more useful there.

Etienne

1 January 1916

My dear father,

I see that Gordon Nicholson has enlisted. Tell Philippe that it’s not necessary for him to follow. Tommy Dunton, the son of the former Montreal notary, with whom I am here, was telling me this morning when we were talking about Philippe: “There is no need of his enlisting. There are enough of you fellows here already!”

Etienne

IT WAS THEN THAT ETIENNE HEARD THE GOOD NEWS: that in view of his proficiency in mathematics, he was to be given a position in the artillery. Intensive and rapid preparations were required, as they were looking for artillery to be in place at the Front within four weeks.—(BB)

11 January 1916

My dear mother,

As you can see, here I am finally transferred to the artillery. You know that I had always wanted to join the artillery, but I didn’t know that it was possible. It was on the 30th of December that I made my request. The adjutant announced to me on Sunday afternoon that I was transferred. Monday afternoon I met my new colonel, and I was taken by the adjutant to my new quarters.

Obviously, artillery is not learnt in one day, and I have several months of hard work prior to being sent to the Front. We are divided into groups of six, one group per gun, and under the direction of a sergeant major we get the gun into position, load, unload, etc. Each person has a specific task, and everything is done absolutely systematically.

Etienne

20 January 1916

My dear father,

Has Philippe then enlisted? Or is that only a prediction? Here I am well established in the Ross Barracks. It seems that I will find some excellent friends. I had my first exam this afternoon. It was topography. One of the questions consisted of translating certain French terms often shown on maps, including: auberge, barrière, and nacelle!

Etienne

30 January 1916

My dear mother,

One mustn’t only lead the men, like in the infantry, but also the horses, and a lot of equipment. My colonel, from the imperial artillery, Colonel Battiscombe, who gives the main part of our courses, told us the other day: “It takes a lifetime to learn all there is to know about a horse, and if you were to get another lifetime after, you could spend it profitably on the same subject.”

What a surprise I had, to read the McGill Daily and see, “A fourth son of Professor Bieler enlists!” How is it that you didn’t tell me that Philippe was going to enlist in the 5th University Company? Anyway, one had to expect it, as Gordon Nicholson had already enlisted. I am wondering when I will see Philippe here at Shorncliffe? I guess he should be arriving soon.

I had a letter from Jean this week, asking me if I could inquire about a promotion for him in the Army Service Corps. I went to see the colonel, and he told me that he couldn’t do anything for Jean here.

Etienne