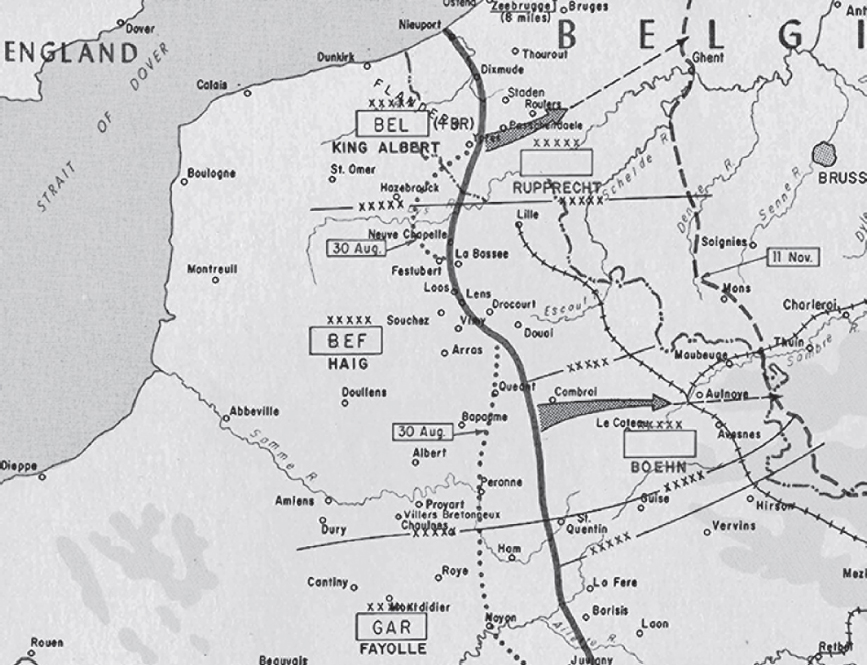

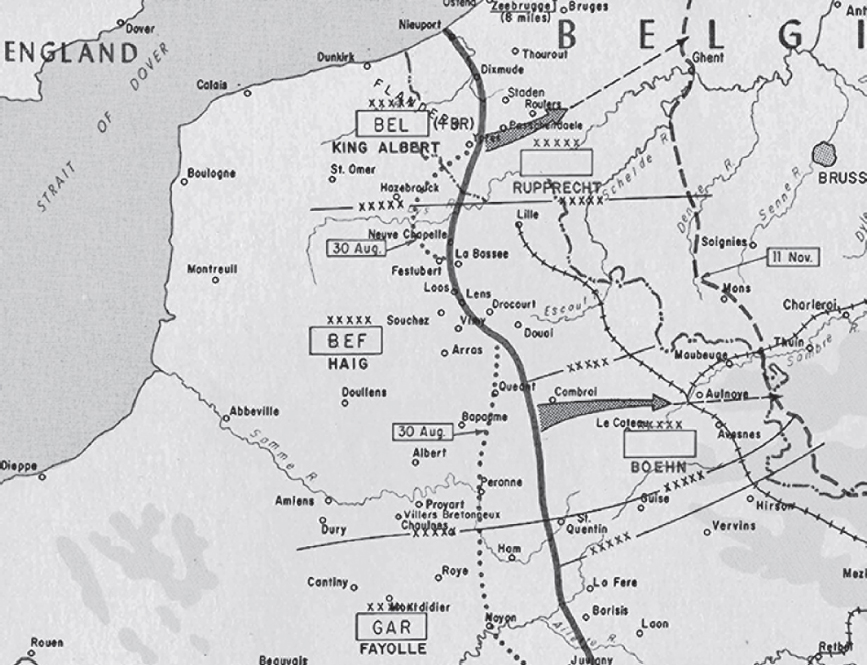

Map of the final Allied offensives on the Western Front, 1918

Map of the final Allied offensives on the Western Front, 1918

GENERAL FOCH INVITED THE ALLIED MILITARY LEADERS, Haig, Pétain, and Pershing, to his headquarters on 24 July, a few days after the Germans cancelled their major Flanders attack. They were pleased with the developments. The rout of the Germans’ Rheims offensive had been extremely costly for them, both in numbers of casualties and in their confidence. For the first time since earlier in the year, the Allies had a superiority in manpower, and each month twenty-five thousand additional US recruits joined the ranks. It was time for the Allies to take the offensive. He proposed that the British assume the offensive in the extreme north, the French in the centre, and the Americans in the south. Haig requested, however, that they should first attack the Amiens Front, in order to free the railways from there. Foch agreed.

ONE DAY AN OFFICER from the High Command asked André to accompany him and several other officers to a meeting where maps and documents were to be exchanged with a French corps that the Canadians were to relieve in Amiens. He describes it as a quite pleasant expedition, involving a trip in a convertible and the eager reception of the topographic data by some doddering French specialists with their long beards, in their splendid villa. The majority were apparently art teachers in the secondary-school system. While the high-ranking officers were having their meeting, André had lunch with the professors, and they celebrated an “entente cordiale.” The meeting took place on 24 July at Maréchal Foch’s headquarters in the village of Sarcus, ten miles south of Amiens.—(BB)

HAIG PROMPTLY INITIATED the Amiens strategy. He named Currie, once again, to mastermind the attack and ensure that the Canadian troops played a prominent role. As the Germans were conscious that a move of the Canadians to a new sector usually indicated an imminent attack, Currie took extreme measures to keep utmost secrecy. Troop transfers were done at night, and a deception operation was created to misrepresent and conceal the Canadians’ position. Much as in Vimy, the Canadian Corps were placed in the middle of the battlefield, with the Patricias at the centre. They would be responsible for striking the critical blow.

A FEW DAYS LATER, another high-ranking officer asked André to undertake an important and very secret mission. He was to go that night by motorcycle, carrying maps and a sealed file. Arriving at a certain crossroad, he found an entire Canadian Brigade waiting for him. He had been asked to then open the file, read the directions he was to follow, locate the route from one of the maps, and guide the troops right up to the indicated destination. This was the secret transfer of the 7th Infantry Brigade from their billets in the concentration area towards their battle assembly positions, on 6 August. The program was carried out perfectly, and André reconfirmed his quite unique reputation.—(BB)

THE BATTLE OF AMIENS BEGAN precisely at 4:20 a.m. on 8 August, in the midst of dense fog. The Canadians’ 7th Brigade, with the Patricias in the centre, filed over the Luce River on duckboard bridges. The way had been cleared by six hundred British tanks that had cut through the enemy’s barbed wire and attacked their positions. The Patricias marched forward in high spirits, as they met an everincreasing flow of enemy prisoners. By the end of the day, they were eight miles from the start. They went on for three more days, but not with the ease of the first day, as the supporting artillery wasn’t able to maintain the pace. Then, only a few weeks later, they were back to Arras to join the Allies’ advance to the Hindenberg Line.

German prisoners carrying Canadian wounded to the rear, passing a tank on the Amiens-Roye road during the Battle of Amiens.

By 10 August, the Germans were forced to retreat from the huge salient that they had so brilliantly conquered a few months before. General Erich Ludendorff, commander of the German forces, called it “the Black Day of the German Army.” It was an important psychological moment for the Allies. The faith in victory, which had supported the German morale during these last few months, was shattered. The soldiers were exhausted, and both the politicians and the generals began to quarrel, with some recommending that an armistice be negotiated.

18 August 1918

My dear mother,

You will see in the newspapers what we are doing these days. We are currently camped outside, and we can’t complain, with the beautiful weather we are now having. We have an excellent chef, who makes us some magnificent dishes on an old stove found in a nearby village in ruins. We also have a Ford to fetch the groceries. It’s fun the way she crosses the fields as easily as she runs along the roads. While our officer was on leave, I had quite a lot of responsibility, and I think I did all right.

I will go to England during my next leave. I need to go there to settle certain matters, and I am also very anxious to see Etienne. Unfortunately the leave is not yet scheduled. It is very difficult to get them these days.

Fruit and vegetables are extremely rare around here this year. The farmers didn’t plant anything this spring, because of the Germans. They are sad not to be able to make any cider, as there are no apples.

André

AS THE SUCCESSES OF 1918 started to accumulate, the Canadian Divisions began moving northward to rejoin the British Army’s march towards the east. On 26 August the Battle of the Scarpe took place. The 2nd and 3rd Divisions pushed the Germans another five miles, but the casualties were heavy, including Jean’s good friend Major Georges Vanier, who lost his leg. Then, the Drocourt-Quéant line, which was viewed as one of Germany’s most powerful defence systems, fell into the Allied hands after a very vicious battle.

La Clairière, 29 August 1918

My dear boys,

We will read a few short verses from the big Bible, and pray for the victory that may follow the uninterrupted march that we have just read about, and we pray also for the European families that we love so much, and especially for our soldiers. We are presuming that the Canadian advance is giving the topographers so much work that André finds it impossible to write.

Blanche

Les Colombettes, 17 September

My dear boys,

The memorable events at La Clairière are not as important as the apparently decisive ones in the European battlefields. They can include a successful mushroom-picking expedition, or an unproductive wild-gameshooting expedition.

However, we have had several more important events. On 7 September we raised a slightly creased Swiss flag to salute the arrival of Mr Isele, the official federal representative of Switzerland, who came to spend twentyfour hours with us, along with his wife and son. They seem to be enjoying the countryside, as they have had to spend all summer in town to settle a number of different matters, amongst which is the internship of Germans in Canada.

Charles

My dear parents,

Let’s Go! We aren’t yet there, however, but everything is moving and there is nothing more encouraging. The topographic service is always on the lookout and moves often.

At the time of the victorious pressure on Quéant, we had to pack our bags rapidly in order to keep in contact with the great advance. We march, and in the destroyed villages, now evacuated by the enemy, we see refugees wandering, having come on foot from far away, to look in the ruins for the location of the houses where the family had lived for several generations! Groups of poor uprooted people search in the rubble for some revealing item, and are delighted if they find a latch or a window bar that could serve to establish the whereabouts of their property. They think that it will take fifty years to rebuild the village and its gardens.

André

25 September 1918

My dear father,

Your letter of 4 September didn’t arrive, because there is no sergeant major to receive it. If I don’t write often, don’t put all the blame on the torpedoes but more on the insufficient non-military news, and a job as routine as civilian life.

I went to visit my old battalion the other day. Most of my old friends are gone, a few officers, but that’s all!

Our greatest privilege is our mess. We have found an excellent chef that helps us to remember our meals at home. Imagine the surprise this evening when we saw on a table with a lovely white wax tablecloth (which cost us thirty francs): two magnificent homemade pies!

It’s strange that many of my friends are getting married these days. They must be seeing the approaching end of the war!

André

Then it was the Canal du Nord, perhaps the most formidable barrier on the road to the east. In what was perhaps General Currie’s most audacious plan, he proposed to construct a bridge that would have to be built by engineers while under fire. Covered by a massive artillery bombardment, on 27 September, the entire Canadian army crossed the bridge. From there the Corps captured the critical Bourlon Woods. Having lost these many key miles, including the Hindenburg Line, the German army accelerated its retreat. General Ludendorff called Prince Max of Baden, newly appointed German Chancellor, on 29 September to suggest that they negotiate a conditional surrender. The chancellor refused.

Les Colombettes, 6 October 1918

My dear boys,

I wanted to attend a commemoration service for the Westmount soldiers killed in the last year, but the weather was so bad that the ceremony was cancelled. It is also possible that the real reason for the cancellation was the Spanish flu that is beginning to ravage the city. One doesn’t want, with reason, to frighten the population, and the newspapers are not very clear on this point, but we are taking precautions.

The news from Europe is incredibly interesting these days. We vibrate with you as we read about these marvellous details of the advance all along the line, when for so long we were marking time. And Bulgaria! What a collapse! And what about Turkey? The people here are complaining that there’s a shortage of turkeys for thanksgiving dinner!

Charles

Cambrai was captured on 9 October, after another difficult and costly Canadian offensive. It was to be General Currie’s final battle in the series that had begun in Arras six weeks before. He had an imposing record: he had fought forward twenty-three miles and liberated fifty-four towns and villages, but at the horrific cost of over thirty thousand casualties.

The further Allied victories in October, and more recent bad news from the Western Front, had badly shaken the Germans. On 4 October, Germany wrote to President Wilson, requesting an armistice. Wilson conferred with his colleagues, and they insisted that it be an unconditional surrender. The Germans refused.

THE EARLY SIGNS of the victory to come, gave both heart and energy to the soldier. The leaves are beginning to fall, the days are getting shorter, and the cold autumn wind is blowing on the backs of the fleeing German army.—(BB)

HRH THE PRINCE OF WALES, General Currie, and the officers of the 3rd Division attended the burial of its former commander, Major General Lipsett, on 15 October. A few days later, the Canadians liberated the town of Denain, and the group took the occasion to celebrate with the population. They were given a heroes’ welcome and were greeted with cheers and shouts of “Vive la France.” French tricolours, long hidden, appeared as if by magic along the route of the marching troops. The Prince of Wales, General Currie, and the others later attended a triumphant celebration that was held in the town square.

HRH The Prince of Wales (second left) with General Currie (left) and the Canadian divisional general whose men captured Denain, standing outside the town’s church, 19 October 1918

2 November 1918

My dear father,

What do you think of the news – an armistice may be signed as you receive this letter! It’s wonderful that the four-year effort has finally come to an end.

We are lodging in a house belonging to a lady who only a few weeks ago was lodging Germans in our room. She has talked to me in detail about the suffering they had endured under the helm of the Germans. The women had to work in the fields for the Germans, and in several instances, she had seen the German officers slap her neighbours for insignificant trivialities. She hasn’t seen any meat for three years, and the American flour was blended with sawdust before being distributed to the population.

Last Sunday, 20 October, I assisted at the mass and great celebration in honour of the liberation of Denain, a small town near here. We had a beautiful drive by car through the village, decorated with French flags, hidden and sewn into their mattresses since the beginning of the war. What joy there was reflected in every face!

We arrived much too late to go into the church, but saw the distribution of flowers to the generals that were there. Then we walked in the streets, when all of a sudden a lovely lady runs after us and invites us to her house. The hot chocolate is on the stove, and she does everything possible to show us her appreciation, despite telling more terrible martyr stories.

She had a great sense of humour, in the classical French style. She showed off her patriotism by crying “Vive la France! Down with the enemy!” ... and she was proud to say that she had hidden the hens, and the Germans hadn’t had one single egg!

Then she showed us the small dirty stable where she had lived for five long winter months while the Germans occupied her house. The French newspaper was stuck onto the front door, and the crowd read thoroughly every word with surprise. It no longer mentioned the great German victory that they had been accustomed to read about.

There’s a procession in the main street, the troops march in an impeccable formation, the civilians raise their hats, but they have suffered too much to be able to shout their cries of joy. A gap in the procession, and here marching are ten old veterans, at least seventy years old, carrying their dear flag, which had been buried for many years. The crowd welcomes them and applauds them with great gusto. At the foot of the statue to Maréchal de Villars, officers of all ranks are grouped around General Currie and the Prince of Wales. Then the mayor gives his speech. Or, in fact, he is supposed to speak, but in reality it’s Madam the mayor’s wife who does and says everything, while the mayor, a little bit behind, approves by nodding his head.

Lots of love to all. Haven’t yet received the pipe, but thanks for the birthday package.

André

THE CANADIANS COULDN’T be delayed by the festivities. They then resume their march, constantly pestered by the stubborn enemy, and the topographers followed. On 10 November, they arrive at Valenciennes, that former lace-manufacturing centre, now the city of steel. The soldiers are lodged as best they can be in the municipal buildings, and André’s office is in a deserted school, humid and freezing. The next day, André, feeling the first shivers of the flu, all the same joins in to the wild rejoicing that bursts in every direction as the liberation is announced. He wrote: “Celebrations, parades, speeches, flag presentations, nothing was missing at the ceremony where the civil authorities were given back the governing of their town. It was a magnificent victory day.” The Canadians then crossed the Belgian border and advanced towards Mons, where an unforgettable reception was waiting for them.—(BB)

GERMANY FINALLY ACCEPTED President Wilson’s conditions for a military armistice on 20 October. It was received with dismay by many in Germany, and it was only on 8 November that General Foch met with the German Armistice Commission in a railway carriage parked in the woods of Compiègne. The Canadian troops meanwhile had marched to Mons, in Belgium, where the war had started in 1914.

On 11 November at 6:30 a.m., a message was sent to the Canadian Corps Headquarters, announcing that hostilities would cease at 11 a.m. that day. The world rejoiced, and work stopped for the rest of the day for all who had heard the good news.

AT THE BEGINNING OF SEPTEMBER 1918, Etienne had once again the pleasure of working a little while as a technical consultant in a naval station near Boulogne, and to see Jean, before going to the hospital to have a further operation on his inadequately healed leg. On 11 November, it’s from his bed in Camberwell that Etienne sees the waving of the hats, the light of the torches, and the joyous sound of cries, songs, and band music. Despite the flu that dominated the room, despite this annoying quarantine, the sick were just as joyous, but less noisy than those on the street.—(BB)