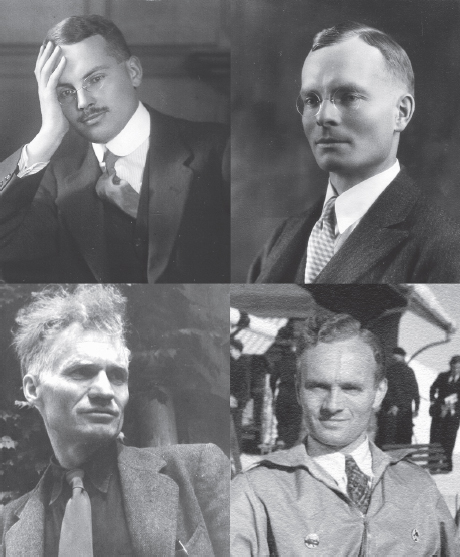

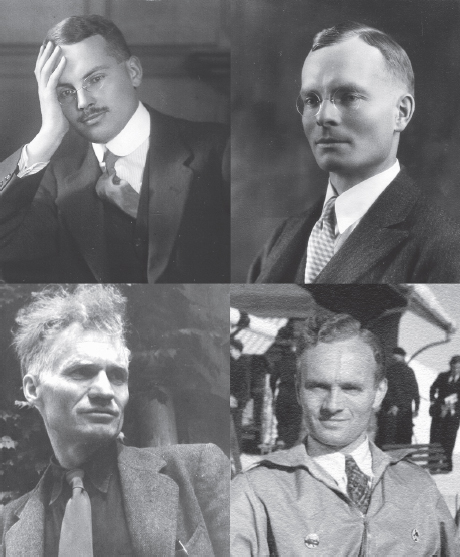

Montage of (clockwise from upper left) Jean, Etienne, Jacques, and André Bieler

Montage of (clockwise from upper left) Jean, Etienne, Jacques, and André Bieler

JEAN SELDOM TALKED about his professional life, but finally, urged by his two brothers, he typed up a brief life story a few years before his death in 1976. This is the part dealing with his years at the League of Nations between 1919 and 1941.

AT MY RETURN HOME IN August 1919, my mother announced that she had a big secret that she would only divulge at the end of the meal! It was that Sir Herbert Ames, the Member of Parliament for Westmount, was looking for a bilingual secretary to accompany him overseas. I met with Sir Herbert, and he explained rather coolly that it was a job in the League of Nations administration, but that I wouldn’t be qualified because of my lack of stenographic competence. I was very much surprised a few days later, to hear that Sir Eric Drummond, Secretary General of the League of Nations, had wired that it was a private secretary that he required, not a stenographer. I accepted their offer.

In hindsight it’s difficult to describe my most vivid impressions during these first and most-important phases of my career. The meetings of the League of Nations, structured in a strict and unchanging fashion, fade in my memory. I assisted probably at the opening and the closing of all of the sessions and a great many council meetings. I was present during the historic sessions, during which the procedures were adopted, Germany was elected to the League, the Disarmament Conference was created, China was left to its own future, the sanctions against Italy were voted, and finally the USSR was excluded from the Institution. I can remember the moving speech when Guiseppe Motta, during the first meeting in the Reformation Hall, called for the universalization of the League and the admission of Germany; of the forceful calls by Ramsay MacDonald and Edouard Herriot presented in the same Hall in favour of the procedures; the conciliatory speech from Gandhi at the opening of the Disarmament Conference; the unconvincing explanations by Sir John Simon to justify the negative attitude of the Leading Nations towards China; and the noisy entry of Goebbels, at the Electoral Palace, surrounded by bodyguards, during the 1933 Assembly. I was also always present at the debates between Albert Thomas and Carl Hambro in the cramped and overheated chamber at the Quai Wilson, where the Finance Commission met. I remember the great discouragement resulting from the world crisis presented by Albert Thomas at the Control Commission, three days before the death of the director of the Bureau International du Travail; the courteous and always satisfying meetings with Sir Eric Drummond in his plain office in the old building, and much more frightening ones with his successor, Joseph Avenol, in his luxurious office in the New Palais des Nations.

I also remember a trip to Rome in May 1920, for the Council’s fifth session, which had been delayed by the Wagons Lits strike, and we had been forced in the waiting room to join the dignitaries of the Church on their way to the beatification of Jeanne d’Arc. We arrived in Rome the next day, where the revolution seemed about to erupt. We were nevertheless able to create the secretariat, ratify the nominations, and sketch the organization of the Justice Department prior to meetings at the Senate and at the Agricultural Institute. On Sunday it was the beatification at St Peter’s and a magnificent reception at the French Embassy, where I wore a white tie borrowed from a hotel clerk!

League of Nations, Geneva, 1921. Front row, left to right: Dr. Nansen, Secretary, Refugee Affairs; Sir Herbert Ames, Finance Secretary. Back row, left to right: Sir Eric Drummond, Secretary General; Jean Bieler, Deputy Finance Secretary

League of Nations session. Jean Bieler, fourth from left at the head table

On 14 February 1930, I married Raymonde de Candolle, a descendant of the botanist, Augustin Pyramus de Candolle.

Time went on, and the League grew. The Quai Wilson building became too small, and plans were made to build something more substantial. My pessimism was such that I found the plans too grandiose and too ambitious. However, in my capacity of Deputy Treasurer and a member of the building committee, I was involved with all the complications. We moved in 1936, but it wasn’t until 1938 that the final Assembly Hall was finished. The inauguration was particularly depressing. Bruno Walter directed the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande for the opening concert, where the various pieces, particularly “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik,” will remain imprinted in the memory of the audience. Two days later, the Agha Khan, the president of the Assembly, whose candidacy depended on his extreme wealth, received the guests in the Great Green Marble Gallery. The fifteen hundred guests were in a state of anxiety, and were thinking more about Hitler’s Machiavellian plans than the questions listed in the Assembly’s agenda. During the dinner given by the British Delegation, we were shocked to hear about a visit to Berchtesgaden, and relieved to talk about one at Godesberg. The anxiety and concerns increased as the session terminated in a spirit of intense pessimism. The few diplomats still in Geneva were preparing to leave, and we were already assuming that, in the days ahead, Paris would be flattened by German bombs.

The 1939 Assembly was held under the auspices of war. Help for Finland was the main subject on the agenda, and Switzerland was granted her wish that the European conflict would not be discussed on its neutral territory. A massive reduction of employment in the secretariat was also voted.

The months go by; Holland, Belgium, and France are invaded. The secretariat prepares to move to Vichy. But despite the Germans’ rapid advance, the decision is taken to leave the secretariat in Geneva. Mr. Avenol, devastated by the fall of his country, quits after some unpleasant discussions, in which I am involved. The direction of the secretariat is given to Sean Lester, who is instructed to manage the transition of the League, as agreed in the Versailles Agreement, and the new organization that will be born from the United Nations victory. Given my position of secretary of the Finance Commission, I was asked to partake in the closing meetings of the League of Nations. Reduced to a minimum, the secretariat did its best. The meeting that was to be held in Lisbon to settle a few problems was blocked by the Germans, and I returned to Geneva to manage the secretariat. In April 1941, my old friend Arthur Mathewson asked me to come to Quebec and assist him with the finances of the Province. I accepted, and resigned from the League of Nations in 1941.—(Jean)

JEAN SERVED, AS DEPUTY MINISTER OF FINANCE OF THE PROVINCE OF QUEBEC, under five premiers: Adélard Godbout, Maurice Duplessis, Paul Sauvé, Antonio Barrette, and Jean Lesage.

ETIENNE RETURNED TO CANADA IN FEBRUARY 1919, and immediately went back to McGill, as both a student and an assistant in the Physics Laboratory, under the able guidance of Dr L.V. King. Since the family had sold Les Colombettes, and as Blanche was leaving for Florida with André, Etienne moved in with Jacques in his basement lodgings at the Presbyterian College. At the end of the semester, Etienne was awarded an MA in Science, with distinction.

Meanwhile, in 1920, Sir Ernest Rutherford had been appointed to the Chair of the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge, and was looking for some of his former students to join him. One was James Chadwick, with whom he had worked during his tenure at Manchester University. Another was Etienne, whom he had known at the British Admiralty. The Chancellor at McGill conveniently helped to arrange for Etienne to receive the “1851 Exhibition” Scholarship, with which he entered Caius College, Cambridge, and became a Research Student at the Cavendish Laboratory. It was a time when the inner citadel of the atom was assaulted by bombardment with the alpha particles of radium, and Rutherford had shown that the mass or weight of an atom is concentrated in a relatively small nucleus.

James Chadwick, who was later to prove the existence of neutrons, and was a key player in the US’s Manhattan Project, had this to say about his colleague:

Etienne joined me in an investigation of the collisions of alpha particles with hydrogen nuclei, which I had just begun. From our observations, Bieler and I were able to show that at large distances the force between the particles was given by Coulomb’s law, and to fix with fair accuracy the point of departure from this law. Bieler then took over the natural development of these experiments. I think that the chief conclusions eventually reached by Bieler may be put thus: that the collisions of alpha particles with light atoms disclose the complex structure of the nuclei and that the effective sizes of the nuclei may be determined in this way; and that at very small distances the force between two charged particles is no longer given by Coulomb’s Law, but a new force, varying very rapidly with the distance, comes into action.

It is perhaps unnecessary to point out the importance of Bieler’s contribution to our knowledge of the atomic nucleus.

Cambridge 1929

In his spare time Etienne enjoyed the company of his colleagues and quite often his brothers, whether it was André in Paris or Jean in Geneva. At Cambridge he ran with the “Hare and Hounds Club.” This group of geniuses would sprint through the fields and the woods, sliding under the hedges, leaping over streams and fences, and at dusk, soaking wet, covered in mud, and out of breath, they would arrive at an old inn and have a big meal in a jolly atmosphere filled with laughter and singing.

His trips were sometimes more serious. He had worked with Bohr, Bragg, and Rutherford, who introduced him to the Duke of Broglia, to whom he talked about his relationship with the Noailles and the d’Aubignés, and the problems of Theoretical Physics. On one occasion he met Madame Currie. She was in mourning and looked worn-out. One would not have guessed that this little woman was the great lady who had been heaped with honours. “She spoke,” wrote Etienne, “in a soft, unassuming voice, as she introduced me to one of her technicians, who was in the process of condensing radium residues for hospitals.”

Etienne’s research, with Rutherford and Chadwick at his side, was timeconsuming, particularly as he was concurrently preparing his PhD thesis. In June 1923, he presented his thesis, “The Law of Force in the immediate Neighbourhood of the Atomic Nuclei,” and was awarded a PhD. He returned to Montreal in the summer of 1923 and was appointed Assistant Professor of Physics at McGill. His new assignment was to be director of studies of the faculty of Physics.

University administration began to absorb most of his time, so that it was only in the evening and weekends that he could tend to his beloved research. Having become an authority on radioactivity, he began to be interested in the theory of magnetism. It was during this time that he also began to think that practical applications of scientific discovery might in the long term be more useful than pure theory. He thought of the untapped resources of Canadian geography. McGill had been approached by the Alderson and MacKay mining company about finding a physicist who might be interested in inventing a piece of equipment to generate better information on the location of ore bodies. They suggested it to Etienne and H.J. Watson.

This was Etienne’s opportunity to explore the field of geophysics. Watson and he evolved a scheme for exploration within a large insulated loop laid on the ground, through which passed an alternating current of a few amperes. By induction, the conducting ore bodies out of sight beneath the ground responded with a secondary current, allowing for the joint electro-magnetic field to be explored with suitable receiving coils and headphones. This work took them to some of the famous mines in the Rouyn district in northern Quebec. The outdoor life, the stimulation of a new problem, and the association with mining men and geophysical prospectors brought a new zest to life, and produced a conflict between his love of pure physics and the attraction of a lively practical problem.

IN 1916, the chairman of the Australian Development and Migration Commission made inquiries in London, which led to an agreement being arrived at between the Empire Marketing Board and the Commonwealth government for an Imperial geophysical survey to be conducted in Australia over a period of two years from 1928. McGill was approached, and Dr. Eve was consulted. Eve was quite keen to be involved but, following conversations with McGill’s chancellor, Etienne was chosen as the candidate to direct the survey, to be supervised by Broughton Edge, a London physicist. The object was to try out the best physical methods as thoroughly as possible in the course of two years’ fieldwork, and at the same time to instruct young Australian scientists in the theory and practice of the methods and in the correct use of the various delicate instruments involved. The primary purpose of the survey was to test the methods, rather than to open new fields.

Etienne, as Deputy Director of the Imperial Geophysical Experimental Survey, arrived in Australia in July 1928. He had complete charge of the work in the absence from the country of Mr Broughton Edge. He came armed with his magnetoelectric device, now called the Bieler–Watson Radiometer, which was to be compared with the various other current devices.

To supervise teams spread out not just in a province, nor a country, but also over an entire continent, is quite different than going down the stairs to McGill’s lecture hall and into the students’ laboratory. In addition, due to the differences in the gauge of the rails, he had to change trains six times while travelling across the country. In the deserts it was usually on foot through soft sand, dragging a caravan, carrying tents, equipment, and all other items required by nomads. After each of these long trips, he faced the extensive administrative details, as well as side trips to the University of Melbourne to analyze and prepare reports and conclusions. In March 1929, he wrote: “As time goes by, we begin to realize the immensity of the job that we need to squeeze into these two years. The practical work will finish at the beginning of 1930, and we still have several far-off regions to explore. Then we will have to coordinate this mass of information and prepare the final report.”

In Tasmania in the early summer of 1929, he wrote to his mother about the evolution of his religious beliefs: “You are right, I am not in a religious atmosphere on this continent, but that fact allows me perhaps to think out these questions more independently. As I study the modern scientific viewpoint, with its confirmation of the organic unity of creation, and of the gradual evolution of inanimate nature towards life, as one of the natural results of the laws of matter and energy, some of the old biblical beliefs fail to satisfy me, and I tend towards a conception of God that is less personal, but no less real, and certainly not less noble. And still, when I think of the personalities whose lives and actions are inspired by biblical ideas, when I think of the legacy, which they have left behind, a heritage of noble example and sturdy moral traditions, I realize that conceptions can never replace convictions, and I ask myself how this treasure can be preserved for our descendants. I see two sides to the revelation of God in the world, one involving the physical the other involving the soul: it seems to me that it should be possible to find a synthesis of these two.”

In July in Australia Etienne headed for the Western beaches, where his team was waiting for him. He started to shiver during the train journey. They would have liked him to stay in Perth, but he insisted on going on to the setting sun. At Geraldton, a tiny port on the shores of the Indian Ocean, the fever halted him. He was transported to the hospital, where the doctor concluded that it was pneumonia and worked hard to save him. After thirty-two hours of great despair, Etienne, who has already conquered the hearts of all those around him, says that he’s feeling better and appears to want to sleep. When the nurse came in a little later, Etienne’s dear face appeared illuminated, but he was very pale and strangely immobile.

Portrait of Ernest Rutherford (left); General Currie, Commander of the Canadian troops in France (right)

In Geraldton, not only the geophysical team, but also the church and the civic leaders, deeply touched at the thought of the sacrifice of this young life, led him to his last home, and erected a monument on his grave. At McGill, on 27 October, the hall was jammed for a solemn service in his memory.

(An excerpt from a letter Sir Ernest Rutherford wrote to Blanche Bieler in October 1929)

His work with me in Cambridge was of fundamental importance and gave us the first evidence of the laws of force around a nucleus.

Sir Ernest Rutherford

(An excerpt from a letter General Sir Arthur Currie wrote to Blanche Bieler in October 1929)

I was drawn to him first when I recognized in him a comrade in the great adventure. When I came to know more about him, to learn his gentleness, his kindly nature, his love of the good and the beautiful, his attachment to his home and his family, I realized that he, for one, had not been dazzled, even momentarily, by what some may call the glamour of war, that it was only his strong sense of duty, his just appreciation of the issues involved, for he had a mind above his fellows and could detect those issues clearly, his hatred of shams and hypocrisies, his sense of what was at stake, that led him to enlist when freedom’s trumpet called her sons to battle.

General Sir Arthur Currie

ANDRÉ WAS VERY ILL when he finally arrived back in Canada in April. His lungs had been badly burnt by the gas. He was classified as a war invalid, with a pension, who could not begin any professional activity. It was summertime at La Clairière, where his family and the Laurentian air compensated for his constant pains. Come the fall, the most important next step was to go to a warm climate.

André and Blanche left for Daytona Beach in October, equipped with a suitcase full of artist’s supplies. Blanche was a talented lady, but by year-end she had taught him everything she knew about art. She enrolled him at Stetson University, where he pursued his education with a more qualified teacher. From there, he wandered northward, staying for a while at a US veterans’ hospital, prior to enrolling at the Woodstock Summer School. It was an important moment for André. There he met his future art teacher, Charles Rosen, and was surrounded with an enthusiastic group of fellow artists, many also veterans. On his return to Montreal, in the family’s new house, located in downtown Montreal, just across the street from McGill, André’s health declined.

In February 1921, Blanche and André left for Bermuda. It was a relaxing and beautiful few months. He was anxious to get back to the Woodstock Summer School, while Blanche was actively planning his future. She felt that he should go back to his roots in Switzerland, where he could work with his uncle, the wellknown Valais artist Ernest Bieler, and perhaps spend some time in the warm climate of Provence. André sailed to Europe in late 1921, and headed for “Courmette,” a convalescent home in the Provençal Alps. Blanche and Etienne joined him there in April 1922, and they travelled together in Italy prior to his joining Oncle Ernest in the Valais.

Oncle Ernest had a major commission to paint a fresco in a church a few miles from Sion in the Valais. André joined in, and, in the following three years, he spent the majority of his time with his uncle, learning the intricacies of his profession. At one point Oncle Ernest suggested that he study in Paris. He spent five months in the spring of 1923 at the Académie Ranson, and the École des Beaux Arts. He was excited by the atmosphere and the people, sometimes seeing some of the greats, like Gauguin. Unfortunately, the climate didn’t suit him, and he returned to Oncle Ernest, Lac Leman, and the Valais. There were several trips: one with Etienne to Italy, where he admired the classics as well as the scenery, and of course the people. He had seen many specialists about his health, and with their help, and considerable patience on his part, he began to feel better. In December 1925 he joined Jean in his new apartment at the Cour St Pierre in Geneva. He was painting actively and, as usual, making many friends. He had his first oneman show in Montreal, and then one also in Geneva. In the summer of 1926, André began to show a real sense of joyous anticipation of his return to Canada. There was a greater self-confidence in his work, but he was eager to find the right milieu, where he could relate his humanist interest to the Canadian habitant. He returned to Canada on 26 September 1926.

After so many trips back and forth across the ocean, it was heartening to witness a reconstitution of at least a part of the Bieler family: Etienne seemed to be in Montreal permanently, André was setting up a kind of studio in the annex to the Methodist College, and Jacques was soon to return from England. André, however, was keen to find a place in the relative isolation of a community where he could continue the sort of creative exploration of the land and the people that he had found so rewarding in Switzerland. He sought it first of all in the Gaspé, but soon discovered the ideal location: the village of Ste-Famille, on the Île d’Orléans. It seemed perfect in every sense, the population with their ancient customs, a virginal countryside, the gracious hills, and the distant views of the St Lawrence and the mountains. He didn’t hesitate, and rented an old house at the edge of the village.

Montreal art critic Robert Ayre said of André, “Humanity is André Bieler’s subject … he isn’t any kind of missionary: he is a painter.” André did just that during his four years on the Île d’Orléans. He painted the churches, he painted the landscapes, but his main subject was always the people. In many ways, he carried on with his uncle’s tradition, where he had specialized in portraits that the Canadian artists of the day avoided. André felt that a landscape with no figures was often incomplete.

Wanting to rejoin the mainstream of art and renew friendships, André decided to return to Montreal in 1930. His return was to a city already scarred by the Depression. The unemployed used to flow like two rivers along St Catherine Street; artists were to struggle equally against apathy and the prevailing attitude that art was a luxury. The artists all knew each other, and all thought that they were going to change the world. André was nicknamed “the artist.”

In 1931, André married Jeanette Meunier, who was in charge of Eaton’s “l’intérieur Moderne.” Together, they designed modern steel furniture that wasn’t known in North America. With a few of their artist friends, they created the “Atelier,” an art school that they were forced to close in 1933. André made posters for the Canadian Celanese Company. He was recognized for several unique achievements in the early 1930s, including what was probably the first true fresco in Canada. It is a striking portrait of St Christopher carrying the infant Christ on his shoulders, painted on the outside wall of a house owned by André’s brother Jacques.

In 1936, Queen’s University established a Chair of Fine Arts. Later that year, André was appointed as resident artist. At that time, only two other universities in Canada offered courses in art for degree credit. In 1940, curious to discover more of his country, André obtained a position to teach painting at the Banff Summer School. But during these years, André’s paintings remained centred on the life and land of rural Quebec, to which he returned in the summer for sketching sessions,

In October 1940, F.P. Keppel, president of the Carnegie Corporation, visited R.C. Wallace, principal of Queen’s and together they made an unexpected call on André in his studio. They invited him to sketch out his idea of a meeting between artists of the east and west, to discuss their mutual problems and to learn about modern developments in the profession. Following a series of talks, moredetailed plans were drawn up, and Keppel concluded that this could be a really significant meeting, and that he would help to fund it.

The structure of the conference was André’s plan. His concern for the position of the artist in society in North America had some basis in his experiences in Switzerland, when he worked with his uncle on the fresco in Le Locle. The conference was open to all Canadian artists of professional standing, to art critics, and to educators. The National Gallery arranged for an exhibition of Canadian art. The conception of the conference was both idealistic and practical. It was attended by over 150 delegates; the list of participants read like a catalogue of Canadian art history of the early twentieth century. It was the instigator in the establishment of the Canada Council in 1957.

In 1969 André was awarded an honorary doctor of laws degree by Queen’s University at the convocation on 31 May, and was invited to give the convocation address. Earlier he had been awarded the Order of Canada

BACK IN MONTREAL, in the spring of 1918, the YMCA had launched a farming program for young students, and Jacques had convinced his principal to schedule the exams early so that he and his mates could enrol. He endured long and tiring hours of farm labour, then, in the fall of 1918, as Jean and Etienne were making their final contribution to World War I, Jacques entered McGill. This was a year devoted to pre-engineering, and Jacques was not impressed with the courses or the professors.

During the summer of 1920, he began more serious occupations. As a junior engineer, he helped to supervise the construction of a new factory for the Canadian Fur Company, which was conveniently located near La Clairière. Two years later, he spent his holidays in Cleveland at the Bailey Motor Company, prior to receiving his engineering degree. With his degree in hand, while wondering what he should do, he got an offer from the Bailey Company, and he moved to a pleasant suburb of Cleveland. Mr. Bailey was a hard-working Puritan, and the privilege of working on his projects demanded a type of slavery, but Jacques recognized the value of the apprenticeship, and was devastated when US immigration forced him to return to Canada.

A friend then told him, “Go and see the International Paper Company.” He followed the advice, and was soon in the Gatineau helping to survey the limits of a huge dam and reservoir the size of Lake Geneva. It was a great opportunity to be in a lovely corner of the Laurentians, working with a team of colourful lumberjacks. He remembers that Christmas Eve, when they left in a long line of red sleds on a layer of white snow, shaken by the holes and the ruts, along narrow roads towards a lunch stop, only to take off again at great speed to a wonderful Christmas feast at home.

As the winter activities were less exciting, and he longed to be in Europe, he decided to join his old friends at the Bailey Company in London. He enjoyed his work there as a junior engineer involved in various foreign operations, although he found that the English engineers lacked the culture of the Germans and the French. There was some wonderful compensation during his travels. On one occasion he joined Etienne and André in a few hilarious days in Paris, and on another occasion he spent time in Italy with his friend Crawford Wright.

On his return to Montreal in 1929, given his experiences at the Bailey Company, he had little trouble in landing a job at the Dominion Oilcloth Company. During the Depression, Jacque’s activities were reduced and became somewhat monotonous. However, as business picked up, everything changed, and he played a key role as a senior engineer in charge of implementing the installation of a new power plant. He was to work there for almost twenty years.

Jacques Bieler in 1935

During his university years, Jacques had been active in the Student Christian Movement, and he and his friends had been influenced by J.S. Woodsworth, whose theme was “Socialism, the Gospel of the Working Class.” Later, in London, he was active in the International Club, where Anglo-Saxons, Latins, Germans, and others discussed world affairs. Then, back in Montreal, a group of young professors and intellectuals, including Jacques, created the League for Social Reconstruction. Their goal was to create a society where production and distribution were more equally shared. Frank Scott, Eugene Forsey, and others got together and published a manifesto. Jacques joined his friends at regular evening meetings to study how Canada could build, on the ruins of the war and the Depression, a more just and less selfish society. It wasn’t a political party or a revolutionary cell, but simply a study group looking for ways to replace “laissez-faire” with a measure of progress. The league itself eventually disappeared, but was an instigator of the formation of the CCF Party, forerunner of the NDP, in which Jacques became quite active.

Unlike his brothers, Jacques had been too young to participate in the horrors of World War I, and he was almost forty in 1939, when the last hopes for peace with the Nazis crashed. As soon as war was declared, he decided to offer his engineering knowledge to the Allied cause. He moved to Ottawa and was the organizer and director of the Department of Munition’s rocket-manufacturing division. It was there that he met Zoe Brown-Clayton, his future wife, and a future editor of the Montreal Star.

But it wasn’t only work and politics. Jacques was an avid outdoorsman, and particularly enjoyed skiing. He was one of the founders of the Red Bird Ski Club, which produced a number of the leading Canadian Olympic skiers in the 1930s and 1940s. In conjunction with that, he and André rebuilt La Maison Rose, that well-known landmark in St Sauveur, with André’s fresco of St Christopher painted on the wall facing main street.