CHAPTER 1

A Peek into the Human Mind 1

‘The world is a looking-glass, and gives back to every man the reflection of his own face. Frown at it, and it will in turn look sourly upon you; laugh at it and with it, and it is a jolly kind companion; and so let all young persons take their choice.’

—William Makepeace Thackeray 2

The mind supreme

If you were a teenager in the 1990s, you may remember En Vogue’s chart-topping song which went: ‘Free your mind and the rest will follow.’ Western philosophy has celebrated the past three centuries or so—the modern era, if you will—as an era dedicated to the freeing of the human mind. (The eighteenth century, for instance, is known as the Age of Enlightenment or the Age of Reason.) Indeed, this time period has been dominated not only by the rise of Western democracies but also, in parallel, by the rise of scientific thought and technological progress—most spectacularly embodied in the Industrial Revolution.

Even with the benefit of hundreds of years of hindsight, the mind boggles at the sheer number of inventions produced by this revolution—the steam engine, the internal combustion engine, the telegraph, the light bulb, the sewing machine and much more.

The human mind created all this, and therefore it stands to reason that the human mind must be a supercharged supercomputer powering the progress of civilization. Baruch Spinoza, the Dutch philosopher, said in proposition twenty-three of Ethics, ‘The human mind cannot be absolutely destroyed with the body, but there remains of it something which is eternal.’ 3 His exaggerated faith in the human mind was symptomatic of the era he lived in (1632–77).

And what of our brain—that physical human organ which is closely related to our intangible mind? The mind might truly be without limits, but psychologists have shown us over the past ten years that there is a gulf between our perception of how powerful our brains are and their true abilities. One manifestation of this gulf is our vision. As a reader, you will confidently claim that you can see this page in its entirety. You are utterly convinced that all of the 300-odd words on this page are clearly visible to you. And yet your confidence is misplaced; eye-tracking software has conclusively shown that when we read a book, our eyes can see only twelve to fourteen letters at a time. The perception that we can see the whole page is actually a visual illusion—we can only see specific points on this page. In fact, while our eyes are focused on this specific word, if the rest of this page were to be altered, we would not be able to notice it. Although in the context of reading a book this visual illusion can be harmless, in other spheres of life—say, professional sport or aviation or warfare or surgery—not coming to terms with the limited abilities of the human eye can have devastating consequences. 4

The irrational mind

The first people to openly question the idea of a rational mind were two brilliant Israeli psychologists, Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman and his friend and collaborator, the late Amos Tversky. In what is the most popular paper written on behavioural economics, titled ‘Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases’ 5, the two psychologists showed how three biases have a bearing on how our brains assess probabilities and predict values:

- Representativeness: We tend to judge or evaluate things based on stereotypes. For example, when introduced to chartered accountants, people assume that accountants can’t think beyond debit and credit, whereas in reality accountants are able to surprise us with occasional bouts of humour as well. In fact, we know a few doctors and accountants in Mumbai who moonlight as performing artists.

- Availability: We take decisions based on instances or occurrences that are first and most easily brought to our mind. For example, we might steer clear of trees on the road after reading in the news that a man walking on the road died when a tree fell on him.

- Anchoring: We get fixated or anchored on the first (or initial) thing we see and use that as a reference point for decisions. For example, when the Nifty hits 10,000 Anupam sells his stocks because 10,000 is optically a very large number that the Nifty has hit for the first time. Therefore, Anupam expects the Nifty to fall after hitting this threshold, and hence sells his investments.

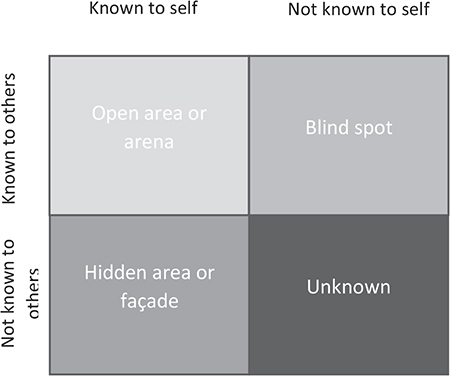

What psychologists like Kahneman and Tversky did was focus on the top-right box of the Johari window (see Exhibit 1), the one that represents blind spots, or that part of our mind which we cannot see but others can. For example, Saurabh does not realize it but everyone else can see that he suffers from ‘anchoring’ when it comes to his travel habits—in the month following a plane crash anywhere in the world, he avoids all air travel (because his mind is now anchored on the crash).

While Kahneman was felicitated with the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002, the validity of his work came into question. In response to a February 2017 post titled ‘Reconstruction of a Train Wreck: How Priming Research Went off the Rails’ by Ulrich Schimmack, Moritz Heene, and Kamini Kesavan, Kahneman admitted 6 that some studies that he relied on were ‘significantly weaker’ than he believed them to be when he co-wrote his 1974 paper. However, Kahneman said that he still believed that ‘actions can be primed, sometimes even by stimuli of which the person is unaware.’

While we view the debate around Kahneman’s work to be a healthy one, we believe that most of us can benefit from the core of his teachings on the limits of the human mind. In fact, as we explain further on in this chapter, the more we understand the human mind, the more keenly we appreciate the pioneering work of Kahneman and Tversky.

Exhibit 1: The Johari window 7

The knowledge illusion

Donald Rumsfeld, the former US defence secretary, was famous for saying, ‘There are known knowns. There are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns. That is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know.’ 8

That is quite a mouthful. There is a simpler and older way to depict this. Created by psychologists Joseph (Jo) Luft and Harrington (Hari) Ingham in 1955, the Johari window is an approach that helps us understand how we see ourselves and how others see us.

This two-by-two grid looks decidedly plain, but delving into these four boxes is the start to better understanding ourselves and harnessing our capabilities.

It plots what we know of ourselves against what others know about us. Each box reveals something different about us. The first box, on the top left, contains the things we know about our own minds that others also know—straightforward enough. The second box, on the top right, contains things about ourselves we don’t know, but others do. The third, on the bottom left, has those things that we know but are hidden from others.

But the most interesting box of them all is the last one, on the bottom right—what we don’t know about our minds and which no one else knows either. The unknown unknown.

Thanks to new technology, the current generation of psychologists are using techniques such as MRI imaging, eye tracking and novel experiments to focus on this box. For example, eye-tracking software revealed that we do not always read text in a linear manner but instead tend to focus only on certain areas.

Not only are they showing the world that the box is far bigger than what anyone else had imagined, they are also identifying some of the reasons which underpin our inability to understand our own abilities (or lack thereof).

In particular, psychologists and cognitive scientists such as Nick Chater, Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach are telling us that we suffer from the following two ‘illusions’. 9

The knowledge illusion: We think we know far more about the world than we actually do. In fact, most of us don’t even understand how basic things like bicycles, toilet flushes and zippers work, let alone understand complex things like global warming, genetically-modified foods, what is inside an iPhone and how Reliance Industries Limited makes money. Anupam once talked to his son’s paediatrician completely convinced that he had become an expert of children’s healthcare. Expectedly, the paediatrician shut Anupam down. Twitter is full of ordinary people ignorantly taking on established subject experts. For example, astrophysicist Dr Katie Mack has become famous for her calm handling of climate change deniers, who are usually people with no qualifications whatsoever in science but with strong opinions on climate change (or the lack thereof). 10

The grand illusion: We perceive our senses to have a richer picture of the world than they actually do. We cannot multitask because our brain can only do one thing at a time and our memory is extremely fallible. In fact, we actually remember the past only in bare-bones outlines but because our mind fills in the gaps with colours and sounds (which often have no bearing with the real world). We often mistakenly believe that we can recall the past in vivid detail.

Let us delve further into these illusions to understand why our minds struggle to understand the world around us even as we struggle to comprehend the scale of the illusion that is deceiving us.

The hubris of the free mind

Everyone agrees that traffic sucks. But here is the problem: over the past fifty years, urban planners across the world have struggled to predict traffic flows. In spite of sustained efforts to address the problems of traffic jams, we still lack a proper understanding of the dynamic behaviours of urban traffic. The difficulty stems from two distinct factors: the lack of systematic and accurate data on traffic flows across entire cities and the diversity of drivers’ self-adaptive decisions with regard to the routes they take.

To complicate matters further, the advent of GPS has made these decisions even more self-adaptive. In December 2018, we took the Western Express Highway to go to IIT Bombay for the Mood Indigo festival because Google Maps had told us so. But Google Maps had also told the same thing to another 150 people. The result? By the time we reached the college, our friends, who had taken the Eastern Express Highway, reached earlier than us.

Complex traffic flows are like the complex neural networks in our mind. Vanilla or chocolate ice cream, mid-cap or small-cap stocks, route one or route two—there is a battle royale raging in the different factions of your brains over simple decisions. Understanding this chaotic complexity of the brain—and abandoning the computer-related analogies of the brain—is central to coming to terms with its strengths and weaknesses. Neuroscientist David Eagleman describes these neural wars vividly in his 2015 book The Brain: The Story of You 11:

Imagine you’re making a simple choice, standing in the frozen-yogurt store, trying to decide between two flavours you like equally. Say these are mint and lemon. From the outside, it doesn’t look like you are doing much . . . But inside your brain, a simple choice like this unleashes a hurricane of activity.

By itself, a single neuron has no meaningful influence. But each neuron is connected to thousands of others, and they in turn connect to thousands of others, and so on, in a massive, loopy, intertwining network . . .

Within this web, a particular constellation of neurons represents mint. This pattern is formed from neurons that mutually excite each other. They’re not necessarily next to one another; rather, they might span distant brain regions involved in smell, taste, and your unique history of memories involving mint . . .

At the same time, the competing possibility—lemon—is represented by its own neural party. Each coalition—mint and lemon—tries to gain the upper hand . . . They fight it out until one triumphs in the winner-takes-all competition. The winning network defines what you do next.

If choosing an ice-cream flavour stresses so many neurons, do you actually think you can understand this text while responding to pings on WhatsApp? In fact, research has now conclusively shown that the brain cannot multitask—we can only think one thought at a time.

In his path-breaking book The Mind is Flat, Chater shows that while doing something routine and well-practised, humans can do two things at once, like driving and talking. But when anything non-routine is introduced (such as driving and thinking through the budget for your next holiday), then multitasking becomes really difficult. Chater was quoted in a newspaper article as follows:

Most of the things that we find reasonably challenging we can only do one at a time. We think we are multi-tasking but in fact we are jumping from one task to the next quite rapidly, something we don’t have to do if we practice. If we practice we get very fluent at something and it requires almost no mental effort, like driving while listening to the radio . . . We can’t keep mental processes entirely separate from each other. If we are doing routine things that is fine, but if we do something non-routine suddenly other parts of the brain start to engage and interfere with routine things like walking. 12

So the next time you try to respond to an email on your smartphone while listening to your colleague talk about his latest achievement, you should stop and ask yourself which of the two mental processes you really want to engage in. Your brain is better equipped at handling one complex process instead of two. So isn’t it more practical to respond to that email with your undivided attention? Remember the destructive potential of ‘reply all’? When you accidentally used it to declare your undying love for Arijit Singh to the entire sales team instead of just one colleague?

On top of the limitations of the brain, our memories are also fallible. Anupam was absolutely sure that his child’s first movie was Kung Fu Panda (2008), until his wife showed him the photo she had clicked next to an Iron Man (2008) cut-out at the multiplex.

These mental limitations would not have restricted us so much had our memories been powerful. A highly retentive brain would allow us to remember, for example, all our previous choices with regard to ice-cream flavours in, say, the month of September at 9 p.m. in Bandra. It would then retrieve those memories and reduce the amount of neural perturbation involved in choosing a flavour here and now. Unfortunately, our memory is weaker—much weaker—than we perceive it to be. Professor Chater illustrates this using a brilliant thought experiment involving a Royal Bengal tiger, in Chapter 4 of The Mind is Flat.

Visualize a tiger. Surely, you have seen tigers in the zoo, on TV and in books dozens of times. Hence you would have no trouble visualizing this majestic animal. Now ask yourself whether the stripes on the tiger’s body flow vertically or horizontally? Write down your answer on a sheet of paper. How about the stripes on the tiger’s tail—how do they flow? Finally, ask yourself whether the stripes on his leg flow vertically or horizontally? Once you have written down all three answers, Google the image of a tiger and compare your answers with the image. If you have written ‘vertical, horizontal, horizontal’, you either work in a zoo or have superior memory. Hardly anybody gets these basic questions about a tiger right (we didn’t either). By the way, the tiger’s front legs don’t have stripes at all—something which we had never spotted until we went through this thought experiment.

Like the flawed and incomplete image of the tiger we have in our head, most of our memories are manufactured by us—they have a lot less to do with what really happened than what we would like to believe. We imagine our past to a significant extent and in so doing, we invent memories and invent feelings such as nostalgia. Forget the number of stripes on a tiger, sometimes we can’t even remember the combination of the number lock on our bicycles. And we won’t even get into how we have faulty memories of what our spouses wore on special occasions.

The practical implications of the mind’s limitations

There are two clear implications of the limitations of our minds and the fallibility of our memories: first, we are bad decision-makers; and second, our minds can be manipulated easily.

Let us consider the first one. We are prone to making some bad, even random, decisions without fully thinking things through. Faced with the same choices in the same circumstances on two consecutive days, we might take two totally different decisions. On one day, we took Tulsi Pipe Road from Bandra to Lower Parel, and on the next day, we took the Bandra–Worli Sea Link. Both decisions make perfect sense to us and we have the same goal—reaching work on time. And yet, we didn’t have any reason for taking the different routes.

The Indian government’s ever-changing rationalization for the demonetization of Indian currency in 2016 (black money, terrorism, corruption, counterfeiting, etc.), extensively documented in the Indian press, is a public demonstration of post-facto rationalization of a policy decision which must have arisen from a neural storm in our policymakers’ heads. 13

Legendary trader and philanthropist George Soros’s son, Robert, claimed that his illustrious father’s trades weren’t based on grand theories of reflexivity but rather on his back pain. George Soros admitted as much in the book Soros on Soros: Staying Ahead of the Curve 14, in a section on how he found out when things were going wrong: ‘I feel the pain. I rely a great deal on animal instincts. When I was actively running the Fund, I suffered from backache. I used the onset of acute pain as a signal that there was something wrong in my portfolio. The backache didn’t tell me what was wrong—you know, lower back for short positions, left shoulder for currencies—but it did prompt me to look for something amiss when I might not have done so otherwise. That is not the most scientific way to run a portfolio.’

Which brings us to the second issue: our vulnerability to manipulation. As our brain reaches almost every meaningful decision through neural war, it is highly prone to suggestion and manipulation (without realizing that it is being manipulated).

In his book The Brain: The Story of You, Eagleman describes an interesting experiment to illustrate this vulnerability. Alvaro Pascual-Leone, a professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, used transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), i.e. a magnetic pulse which excites a part of the brain, to initiate movement in either the left or right hand. Participants sat in front of a computer screen and were told to raise their right or left hand as the screen cued the colours red, yellow and green. At red, participants made their choice of right or left hand and activated this decision when the lights turned green.

Then, a twist was introduced. A TMS pulse was used when the colour changed to yellow. The pulse was specifically designed to make participants more likely to lift their right hand. Interestingly enough, the participants thought that they changed their decision on their own free will, even though the TMS was influencing their decision. As Eagleman says, ‘The conscious mind excels at telling itself the narrative of being in control.’ In fact, psychologists have shown that the illusion of being in control is even stronger than the visual and knowledge illusions which we have discussed earlier in this chapter.

The susceptibility of the human mind to external suggestion obviously creates the risk of brainwashing not just at the level of the individual but also at the collective level. Followers of cults who commit mass suicide (for example, the more than 900 followers of the Reverend Jim Jones who committed suicide together in 1978 by drinking poisoned fruit punch 15) and ordinary people who become a murderous mob (for example, the people who lynch members of a minority community, or ordinary Germans who ganged up to send six million Jews to their death in Nazi concentration camps) are extreme manifestations of this. Less extreme manifestations are faddish games such as Tamagotchi 16 (all the rage in Japan in 1996), social media like Instagram, and the latest, hottest, must-buy apparel designs.

The same stimulus can provoke different responses in different people

So absorbed are we in our internal world that we often don’t see and hear what’s right in front of us. Why? Because all vision and hearing involves inference and perception, implying that each of us can perceive the same thing differently depending on what our brain has been exposed to before. For example, the language that you are exposed to as an infant refines your ability to hear the particular sounds of your language and, in parallel, reduces your capacity to hear the sounds of other languages. At birth, a baby born in a Bengali family and a baby born in a Punjabi family can hear and respond to all the sounds in both languages. As she ages, the baby raised in the Bengali family will lose the ability to distinguish between the ‘s’ and ‘sh’ sounds—two sounds that aren’t separated in Bengali. (So in Bengali there is no ‘Saurabh’; there is only ‘Shourobh’.)

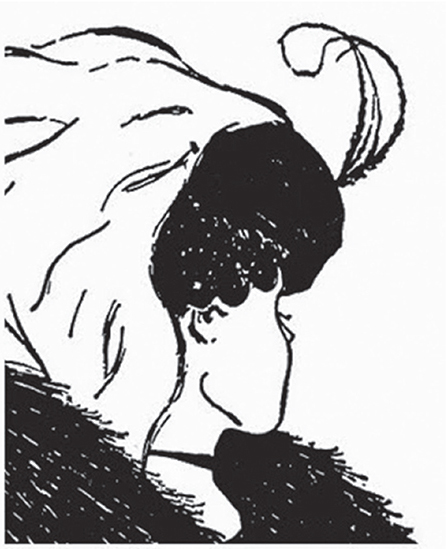

How we are primed in life also has a bearing on not just what we can hear but also what we can see. Many of you would have seen the picture 17 given below. What do you see when you see this picture?

Saurabh usually sees an old woman with a beak-like nose. Saurabh’s wife, Sarbani, sees the profile of a young woman staring into the distance. This phenomenon—where the same image evokes two different responses—is called perceptual bistability. Saurabh and Sarbani see the same image completely differently because their brains have been primed differently during the course of their lives. However, in a further illustration of priming, now that Sarbani has shown Saurabh how the picture also represents a young woman’s profile, Saurabh too can see the young woman!

This phenomenon of the same thing being perceived differently by different people was immortalized by legendary Japanese film director Akira Kurosawa in his 1950 movie Rashomon. In this movie, a murder is described in four mutually contradictory ways by its four witnesses. Since then the term ‘Rashomon effect’ is used to refer to contested interpretations of the same event, subjectivity versus objectivity in human perception, in memory and in reporting. The Rashomon effect arises from, both, differences in our perception of the same event (perceptual bistability) and the weakness of our memory in remembering exactly what happened (especially what happened in complex and/or ambiguous situations). A famous example of such a situation is US President John F. Kennedy’s assassination on 22 November 1963 in Dallas, Texas. While it is clear that former US Marine Lee Harvey Oswald shot and killed the American President, what observers present on the scene still cannot agree upon is whether there was another gunman who also fired a bullet at the president. As a result, half a century on from the tragic event, there are still numerous unresolved questions around this infamous assassination.

Taking shortcuts

So far, we have shown that our brains have limited power and our memories are fallible. The fallout of this is that we are lousy decision-makers and prone to manipulation. If you’re wondering how we survive despite these limitations, the answer is by using heuristics, shortcuts that our brains use to simplify the world for us.

There is nothing inherently wrong with this. These shortcuts or mental rules of thumb help us make decisions and solve simple problems quickly. The problem is that heuristics can also manifest as biases or even delusions.

As toddlers, we loved hearing stories; as grown-ups, we love believing them. Our brain indulges us in our desire to see the world in black and white, just as our body indulges us in our desire to have junk food and skip gym sessions. Unfortunately, many of our stories are based on heuristics as mental illusions and biases.

Cultural stereotypes, for example, reduce our understanding of different people to superficial traits. For a country as diverse and as culturally rich as India, we do a disservice to our own countrymen when we limit our understanding of them to generalities. For example, the stereotype of Marwaris and Gujaratis as being great at business totally ignores the huge amounts of wealth created by entrepreneurs elsewhere, such as in the south. And in Mumbai’s stock market, the ‘Delhi discount’ was denigratingly used to ascribe lower valuations for stocks of companies belonging to promoters from north India.

So what remedies can this book provide?

What can we do to deal with the fact that the human mind is not a computer, the fact that faced with an identical decision in identical circumstances on two consecutive days the brain can make different choices? What can we do to mitigate the fact that even when faced with simple decisions our brain goes into a tizzy? How do we live with the fact that even the same image can be interpreted differently by different people? What can we do to cope with the fact that our brain creates heuristics or shortcuts which are often faulty?

Repetitive practice allows us to reduce the amount of neural processing activity and generate more consistent outcomes. Science has shown that we are able to, quite literally, mould our brains through practice and intense application. Our brains are plastic—not just in childhood but right through adulthood, our brains change physically. Prolonged practice and persistent skill improvement has a marked impact on our brains.

Let us go back to our example of driving. We talked about how we often make suboptimal decisions with regard to routes or brainlessly rely on GPS. The men and women who drive the famous black cabs of London are specifically trained to avoid both of these behaviours. They spend years memorizing every street and back alley in the city. Then they have to sit for and pass a torturous exam called The Knowledge 18, as part of which they are repeatedly given two obscure points in the city and have to immediately come up with the best route.

As we discuss in more detail in the next chapter, neural imaging (or imaging of the brain and its functioning) has allowed psychologists to see how the brains of these taxi drivers change as they go through the long process of memorizing thousands of routes, then passing The Knowledge and then—even more interestingly—becoming experts in the decade after they have passed the test.

The next couple of chapters are centred on techniques similar to these which can be applied to a broader range of professions, techniques which help one build focused specialisation. Then from Chapter 4 onwards we focus on a different set of techniques to increase our efficiency and our effectiveness. Chapters 4 and 5 focus on how to declutter our minds while reducing stress and anxiety. Chapters 6 and 7 delve into juicing up our ability to come up with original ideas at a rapid clip in the context of the highly competitive industries in which most of us have to work. Chapters 8 and 9 then provide case studies of how these techniques have been applied in the real world.

* * *

Key takeaways from this chapter

- Psychologists have shown us over the past ten years that there is a gulf between our perception of how powerful our brains are and their true abilities. We suffer from the knowledge illusion (i.e. we think we know everything) and the grand illusion (i.e. we think our faculties are stronger than they actually are).

- Research has conclusively shown that the brain cannot multitask—we can only think one thought at a time. And most of our memories are manufactured by us; they have a lot less to do with what really happened than what we would like to believe happened.

- Given the above, we are bad decision-makers and our minds can be manipulated easily. How do we survive despite these shortcomings? By using heuristics—shortcuts that our brains use to simplify the world for us.

- What remedies does this book provide? We start with the concepts of simplicity, specialization and spiritualization. We then move on to specific behaviours, namely clutter reduction, creativity and memory, and collaboration. Finally, we provide applications where the solutions and behaviours provide actual results.

Navigating Modern India’s Mental Health Issues with Dr Sharmila Banwat

Dr Sharmila Banwat is an occupational therapist and clinical psychologist practising for more than nineteen years in the bustling suburbs of Mumbai. She believes in and propagates preventative interventions for all age groups of individuals. We met Dr Banwat on 25 May 2019 at her clinic in Andheri, a western suburb in Mumbai, and spoke with her about a wide range of topics, starting with her education and training and how she began her practice. Hailing from a typical middle-class Indian family, Dr Banwat graduated in occupational therapy from Topiwala National Medical College in Mumbai.

During the course, she became interested in psychiatry and psychology and decided to pursue the subjects. After completing her post-graduation in clinical psychology, Dr Banwat worked under Mumbai’s eminent psychiatrists for a year, before opening her own clinic at the turn of the century. Since then she has been testing and counselling a cross section of people who typically live in and around the western suburbs of Mumbai. In 2012, Dr Banwat completed her PhD (in psychology and management) from SNDT Women’s University.

Until about a decade ago, psychiatrists and paediatricians would refer patients to psychologists for psychometric evaluation, therapy or counselling. There were hardly any walk-in patients into clinics then. But everything has changed over time. As mental health awareness has risen, the idea of treating mental health issues, challenges and disorders under the guidance of specialist mental health professionals such as clinical psychologists has also increased manifold. Now, Dr Banwat tells us, there are more walk-ins into her clinic. People check online for psychologists and as word spreads, recommendations from old patients, friends and family have also become a source of patient referrals.

Dr Banwat has an extensive experience of working with children and adults. In the first ten years of her practice, she worked as a child psychologist. Through this period, she gained insights into the family dynamics of children and incorporated family psychology into her practice. As her interest in the subject grew, she underwent training in counselling techniques to equip herself as a psychotherapist and counsellor to treat adult cases as well.

Dr Banwat now sees patients across all age groups: infants for developmental screening; children for cognitive and temperamental issues; adolescents for addressing teenage angst, life-skill training, personality evaluation etc.; adults for mental health check-ups, marital counselling; senior citizens for neuro-psychological assessment and screening for cognitive impairment, dementia or will-making.

The western suburbs of Mumbai have upmarket schools and colleges and from these come children with multifold issues. Of late, she has been seeing many adolescents who are undergoing a range of emotional, behavioural, academic and drug-abuse problems. We are talking serious drugs here—not just marijuana—which are becoming extremely common substances now. Next on the list of problems are relationship breakdowns, because kids even at a young age are in and out of many relationships, leaving them very vulnerable. In some cases, children experience angst because of their family going through distress, their parents’ marital discord or their extravagant social life. Dr Banwat’s experience suggests that addressing unhealthy family dynamics yields good and enduring results. As she says, ‘We need to nip it in the bud.’

Among adults, Dr Banwat sees many people who cannot figure out how to strike a work-life balance. They understand it conceptually but can’t implement it practically—for example, everyone knows they want to leave office at 7 p.m. but find it impossible to do so. Some take sabbaticals to think it through, others switch from one job to another. Everybody has their own trajectory. Some can’t even articulate their problem and reach the psychologist in a state of confusion and distress. Some don’t know what’s happening and where their life is taking them; they see no purpose or meaning, while some have figured out that something is not right but are not able to place a finger on it. Especially in the corporate sector, very few adults accept that they’re going through a mental crisis and understand the need to address it.

And then there are certain stressors or triggers, either at the workplace or at home, such as not being able to do justice to your role as a father, as a spouse, as an employer, or as a boss to one’s juniors. Increasingly, midlife crisis has become a well-recognized issue in India. But how we respond to it is still evolving. In many cases, people just let it pass, expecting that time will heal it. Some people feel that their job is not their calling and that they ended up doing things that were different from what they wanted to do. Some people want to figure out midway through their careers what exactly life has to offer, and this becomes a quest for self-discovery.

These mental issues have ballooned in the past decade. It is tough to pinpoint a single reason. Anecdotally, India is a rapidly developing country. As a society we seem to be moving from a joint family to a nuclear-family system. As a result, not only is the family constitution changing but the support systems available to families and their children have also changed. Add to that the overexposure of children to media and the uncensored availability of a plethora of information at a much younger (and, arguably, inappropriate) age.

Not all of this is bad news though. For the children, there is a lot of hope. Greater exposure to the broader world at a younger age means that children today are more emotionally aware than their parents were at a comparable age. So if we work on the emotional intelligence part and make them stable, then these children can thrive. We can work at a preventative level by teaching teenagers about mental well-being in schools (especially in the age band of twelve to eighteen), in colleges and in awareness talks and group therapies.

For adults, Dr Banwat believes that things need to change at the corporate level. Since companies are now more aware than ever about the impact of stress on work performance, they should be willing to invest in solutions. Such solutions do not just entail making counsellors available for stressed employees but also involve providing ongoing emotional coaching to: (a) help employees become aware of the stressors which characterize contemporary urban life, (b) improve stress management skills, and (c) build resilience.

Dr Banwat repeatedly stresses the importance of emotional coaching because in an upwardly-mobile society, the ‘fear of missing out’ on the best schools, tuition teachers, tutorial classes, activity classes, colleges, jobs, etc. is a big factor. Education has become commercialized and this generation of kids is paying the price for that.

Physical health has a big role to play in mental health too. Dr Banwat believes that three changes in lifestyle can contribute significantly to mental wellness: adequate (seven to eight hours) sleep, healthy food eaten as per a schedule (instead of erratic meals) and regular physical exercise. There is a fourth tip as well: at the end of each day, give yourself ten minutes to self-reflect and evaluate your day—what were the highlights, what were the positive and negative events. This helps break what she calls the ‘compare and despair’ cycle. Instead of comparing our lives to others and despairing over our deficits, we could take time to see how we grow in our own individual lives.

Finally, while explaining how therapy works, Dr Banwat told us about how the rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) approach separates rational and irrational belief systems and works at disputing irrational beliefs (which tend to further creep in when stress preoccupies the human mind) to achieve realistic solutions. When her patients walk in, they don’t have insights into what and how these irrational beliefs are affecting their lives. REBT therapy is aimed at increasing their awareness, their coping skills, and at building resources to strengthen the rational belief systems. Since she believes in preventive measures, she propagates individual- and group-therapy programmes for children starting in grade-I until adolescence, so that they become happy, self-accepting and well-functioning and ready to face the world. Today’s children face not only normal developmental problems but also a myriad of potentially overwhelming stressors unimaginable in previous generations. As mental health professionals, parents and educators, we need all the resources we can muster to help safeguard our children from self-doubt, irrational thinking, debilitating emotions and self-defeating behaviours.

While emotional intelligence must be instilled in children, the good news is that it can also be developed among adults through psychotherapy. Yet another psychotherapy modality used by Dr Banwat is eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for trauma cases. She has found that EMDR delivers faster and more durable results in challenging cases.

At the end of our interview, she told us that work on mental health is not optional but necessary to improve the quality of life by psychologically engineering your mind through objective and empirically-tested methods.