Getting Familiar

To start, go ahead and try these five Logical Reasoning questions. Give yourself no more than eight minutes total. We'll revisit these questions later on in the chapter.

PT7, S4, Q5

The government provides insurance for individuals’ bank deposits, but requires the banks to pay the premiums for this insurance. Since it is depositors who primarily benefit from the security this insurance provides, the government should take steps to ensure that depositors who want this security bear the cost of it and thus should make depositors pay the premiums for insuring their own accounts.

Which one of the following principles, if established, would do most to justify drawing the conclusion of the argument on the basis of the reasons offered in its support?

(A) The people who stand to benefit from an economic service should always be made to bear the costs of that service.

(B) Any rational system of insurance must base the size of premiums on the degree of risk involved.

(C) Government backed security for investors, such as bank depositors, should be provided only when it does not reduce incentives for investors to make responsible investments.

(D) The choice of not accepting an offered service should always be available, even if there is no charge for the service.

(E) The government should avoid any actions that might alter the behavior of corporations and individuals in the market.

PT7, S1, Q1

Before the printing press, books could be purchased only in expensive manuscript copies. The printing press produced books that were significantly less expensive than the manuscript editions. The public's demand for printed books in the first years after the invention of the printing press was many times greater than demand had been for manuscript copies. This increase demonstrates that there was a dramatic jump in the number of people who learned how to read in the years after publishers first started producing books on the printing press.

Which one of the following statements, if true, casts doubt on the argument?

(A) During the first years after the invention of the printing press, letter writing by people who wrote without the assistance of scribes or clerks exhibited a dramatic increase.

(B) Books produced on the printing press are often found with written comments in the margins in the handwriting of the people who owned the books.

(C) In the first years after the printing press was invented, printed books were purchased primarily by people who had always bought and read expensive manuscripts but could afford a greater number of printed books for the same money.

(D) Books that were printed on the printing press in the first years after its invention often circulated among friends in informal reading clubs or libraries.

(E) The first printed books published after the invention of the printing press would have been useless to illiterate people, since the books had virtually no illustrations.

PT7, S1, Q15

Eight years ago hunting was banned in Greenfield County on the grounds that hunting endangers public safety. Now the deer population in the county is six times what it was before the ban. Deer are invading residential areas, damaging property and causing motor vehicle accidents that result in serious injury to motorists. Since there were never any hunting related injuries in the county, clearly the ban was not only unnecessary but has created a danger to public safety that would not otherwise exist.

Which one of the following, if true, provides the strongest additional support for the conclusion above?

(A) In surrounding counties, where hunting is permitted, the size of the deer population has not increased in the last eight years.

(B) Motor vehicle accidents involving deer often result in damage to the vehicle, injury to the motorist, or both.

(C) When deer populations increase beyond optimal size, disease and malnutrition become more widespread among the deer herds.

(D) In residential areas in the county, many residents provide food and salt for deer.

(E) Deer can cause extensive damage to ornamental shrubs and trees by chewing on twigs and saplings.

PT7, S1, Q14

Marine biologists had hypothesized that lobsters kept together in lobster traps eat one another in response to hunger. Periodic checking of lobster traps, however, has revealed instances of lobsters sharing traps together for weeks. Eight lobsters even shared one trap together for two months without eating one another. The marine biologists’ hypothesis, therefore, is clearly wrong.

The argument against the marine biologists’ hypothesis is based on which one of the following assumptions?

(A) Lobsters not caught in lobster traps have been observed eating one another.

(B) Two months is the longest known period during which eight or more lobsters have been trapped together.

(C) It is unusual to find as many as eight lobsters caught together in one single trap.

(D) Members of other marine species sometimes eat their own kind when no other food sources are available.

(E) Any food that the eight lobsters in the trap might have obtained was not enough to ward off hunger.

PT10, S1, Q5

Some people have questioned why the Homeowners Association is supporting Cooper's candidacy for mayor. But if the Association wants a mayor who will attract more businesses to the town, Cooper is the only candidate it could support. So, since the Association is supporting Cooper, it must have a goal of attracting more businesses to the town.

The reasoning in the argument is in error because

(A) the reasons the Homeowners Association should want to attract more businesses to the town are not given

(B) the Homeowners Association could be supporting Cooper's candidacy for reasons unrelated to attracting businesses to the town

(C) other groups besides the Homeowners Association could be supporting Cooper's candidacy

(D) the Homeowners Association might discover that attracting more businesses to the town would not be in the best interest of its members

(E) Cooper might not have all of the skills that are needed by a mayor who wants to attract businesses to a town

The Assumption Family of Questions

Each of the five problems on the previous pages seems to be asking a different type of question, right? Yes, it's true that the question stems are a bit different, but our goal in this chapter is to illustrate that these five questions are actually birds of a feather: they require the same thought process and the same skills. Each one of these questions requires that you identify a core argument being made, and furthermore, that you recognize the assumptions within that core. Each of these questions falls into a broader category that we refer to as the Assumption Family.

The following question types, each to be discussed in greater detail in later chapters, are what we categorize as Assumption Family questions. Combined, these questions make up more than half of all Logical Reasoning questions on the exam:

- Assumption questions

- Flaw questions

- Strengthen questions

- Weaken questions

- Principle Support questions

In this chapter, we will outline the keys to understanding and answering Assumption Family questions. We'll finish by revisiting the questions you've just completed.

The first step is to establish a reading perspective.

Reading from a Perspective

Kennedy-Nixon

The first ever nationally televised presidential campaign debate took place in September of 1960. Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy and Republican incumbent Vice President Richard Nixon squared off in what would become one of the most famous debates in history. The idea of relevant experience had become a major issue in the campaign; the Republicans had cited inexperience as the main reason why Senator Kennedy was unqualified to lead from the White House. The first question of the evening was directed to Senator Kennedy (quoted from debate transcripts):

MODERATOR: Senator, the Vice President [Richard Nixon] in his campaign has said that you were naïve and at times immature. He has raised the question of leadership. On this issue, why do you think people should vote for you rather than the Vice President?

MR. KENNEDY: Well, the Vice President and I came to the Congress together in 1946; we both served in the Labor Committee. I've been there [in Congress] now for fourteen years, the same period of time that he has [referring to Nixon's six years in congress and eight years as Vice President], so that our experience in, uh, government is comparable….

MODERATOR: Mr. Nixon, would you like to comment on that statement?

MR. NIXON: I have no comment.

Perhaps it was a calculated move, but Vice President Nixon seemed to have bought into Kennedy's argument. He didn't even respond.

Most of the time, we tend to go along with people's arguments without much thought. If they speak forcefully enough, or with enough passion (as Senator Kennedy most likely did during the debate), we end up wanting to go along. Let's face it: we're easily convinced and gullible, especially when politicians are talking!

Kennedy's argument above sounds great. It makes sense: 14 years equals 14 years, right? However, there are some inherent gaps in his logic. We'll get to these momentarily.

Assumption Family questions are all about reading an argument, such as the one given by Kennedy above, deconstructing the argument, and identifying any gaps or weaknesses in the logic used to form the argument. Complacency won't cut it. Giving the benefit of the doubt won't work. In order to be successful in this endeavor, you must be super-critical of everything you read, and in order to properly focus your critical eye, you must read with a purpose.

Perspective and Purpose

Have you ever read a paragraph in a book or a magazine and then realized that you can't remember anything that you've read? That sort of situation is perhaps unavoidable in life, but it is something that you can and should make sure to avoid on the LSAT. On the Logical Reasoning section, you will find yourself confronted with arguments and passages on topics that you're not familiar with and not particularly interested in. If you're not entirely sure what parts of the passage are important and what parts are not, the risk of “spacing out” is particularly high. When this happens, you'll find yourself rereading certain sentences two or three times as you struggle to concentrate. You might even decide to start over from the top and read the whole thing over again! This is obviously not a good use of time. So, how can you avoid this?

Research shows that the best readers, and the most efficient readers, all read with a clearly defined purpose. Having a clear sense of why you are reading something, and what is most important to understand about what you read, will help you avoid losing focus. However, there are often situations in life, such as when you take standardized exams, when it can be very difficult to know what your specific purpose should be as you read.

An effective way to define purpose is to consider the perspective of a reader. Here are a few examples to illustrate this point:

| From the Perspective of… | Purpose |

| a beach lounger reading a novel | pure entertainment…no real purpose |

| a mother of two, dinner time, a pound of leftover ground beef in the freezer, reading a cookbook | find recipes that use ground beef (how much time do you think she'll spend trying to absorb the details of a chicken recipe?) |

| a Robert Frost scholar, preparing to give a lecture on Frost's use of “nature's ritual,” reading an anthology of poems by Robert Frost | connect different poems using the ritualism of nature as a theme |

| a sports show host, getting ready to interview Tiger Woods, reading the New York Times the morning after the biggest golf tournament of the year | scan for Tiger's tournament results, look for inexplicable events that Tiger might be able to shed light on in a live interview |

In each of these real-life situations, we can see that the reader's perspective is what determines the purpose of his or her read. For each of these situations, we can say that perspective drives purpose.

Many students read LSAT arguments with a vague or incorrect sense of purpose. Some read LSAT arguments with no purpose at all. This leads to slow reading and low comprehension. To better your chances of success on Logical Reasoning, you need to read quickly, efficiently, and with a high level of comprehension. Having a clearly defined sense of purpose is the key to this, and an effective way to ensure that your purpose is sound is to read from the right perspective.

Reading Like a Debater

Let's revisit the Kennedy-Nixon excerpt in order to define the perspective that will drive your purpose when reading Logical Reasoning arguments. Consider Kennedy's argument one more time:

MR. KENNEDY: Well, the Vice President and I came to the Congress together in 1946; we both served in the Labor Committee. I've been there [in Congress] now for fourteen years, the same period of time that he has [referring to Nixon's six years in congress and eight years as Vice President], so that our experience in, uh, government is comparable….

There are many different perspectives from which Kennedy's argument can be heard or read. Here are some:

1. Reporter. Someone listening or reading from the perspective of a reporter would listen or read with the purpose of accurately transcribing the comments. He or she would listen closely for details (1946, 14 years, etc.) to be sure they were noted accurately.

2. Historian. Someone listening or reading from the perspective of a historian might listen or read with the purpose of connecting the comments to similar arguments made in historical debates, perhaps attempting to draw out comparisons with the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates.

3. Debater. Someone listening or reading from the perspective of a debater (in this case Vice President Nixon) should listen or read with the purpose of analyzing the logic of the argument and attempting to uncover the logical gaps or flaws. You may have guessed it…

This is the best perspective to use for the Logical Reasoning section.

Assumption Family questions will ask you to evaluate the logic of an argument, or to identify flaws in an argument. If you are reading these arguments through the critical eye of a debater, your purpose will be to actively seek out the inherent gaps and flaws. So, as you read, put yourself in the shoes of a debater. Prepare yourself for an effective rebuttal, and when your chance comes, don't be caught flat-footed like Richard Nixon was!

Let's take a closer look at specifically what it is that you need to attend to as you read from the perspective of a debater.

The Structure of Arguments

Imagine yourself in Nixon's shoes. In order to effectively rebut Kennedy's argument, you first need to figure out what the main point of his argument is. What exactly is he trying to say? What is his conclusion?

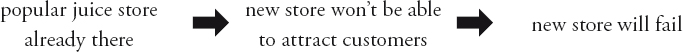

CONCLUSION (main point): “…so that our experience in, uh, government is comparable….”

The conclusion of the argument is the main point, final claim, or main opinion. It is always the most important part of the argument; you must identify the conclusion if you are to have any chance at understanding, evaluating, or attacking the argument. The conclusion is sometimes triggered by words such as so, thus, therefore, and consequently.

Next, you must consider how the conclusion is drawn. Why is this conclusion made? What support is given for this conclusion? What are the supporting premises?

SUPPORTING PREMISE (supporting fact): “…we both served in the Labor Committee.”

SUPPORTING PREMISE (supporting fact): “I've been there [in Congress] now for fourteen years, the same period of time that he has [referring to Nixon's six years in congress and eight years as Vice President]….”

Supporting premises are stated facts or claims that are meant to provide support for the conclusion. Premises are sometimes triggered by words such as “because” or “since” (more on trigger words, or language cues, later).

Once you've identified the conclusion and the supporting premises, you'll be in a good position to be critical of the argument. In this case, the argument is suspect because Kennedy makes a few questionable assumptions.

ASSUMPTION (unstated): Two people who serve on the same committee necessarily gain the same experience.

ASSUMPTION (unstated): The amount of time spent in Congress is a good measure of experience.

ASSUMPTION (unstated): The work of a Senator provides the same relevant experience as the work of a Vice President.

Assumptions are the underlying, unstated elements of the argument that need to be true in order for the argument to work. Almost all LSAT arguments have underlying assumptions. Your job is to actively uncover these assumptions as if you were devising your counter response in a debate. We'll discuss the nature of assumptions more carefully in a later chapter, so don't worry if you weren't able to see the ones above initially.

Assuming Nixon had (1) understood Kennedy's conclusion, or main point, (2) attended to the premises that Kennedy used to support his conclusion, and (3) actively used this understanding to uncover the gaps inherent in Kennedy's argument, he could have responded much more forcefully.

Let's rewrite history:

MR. KENNEDY: Well, the Vice President and I came to the Congress together in 1946; we both served in the Labor Committee. I've been there [in Congress] now for fourteen years, the same period of time that he has [referring to Nixon's six years in congress and eight years as Vice President], so that our experience in, uh, government is comparable….

MODERATOR: Mr. Nixon, would you like to comment on that statement?

MR. NIXON: Yes, I would like to comment. Senator Kennedy assumes that his work as a Senator provides the same relevant experience as my work as Vice President. This assumption is flawed. The executive experience I have gained as Vice President is much more relevant to the executive work that we all know to be the primary work of the President. In fact, our experience is not comparable. I am much better prepared to be President.

When you read a Logical Reasoning passage, take on the perspective of a debater. Perspective gives you purpose, and purpose gives you focus, speed, and comprehension. Make it your purpose to be critical of the argument at hand. Actively search for conclusions, the supporting premises, and the underlying assumptions. Challenge the language that's used, including absolute or extreme words or phrases. In the same way that you would be skeptical of an opponent's argument in a debate, be skeptical of the author's argument in an LSAT passage.

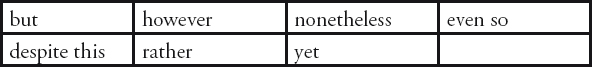

The Argument Core

Definition

Thus far, we've discussed the core elements of an argument. An argument is a premise, or set of premises, used to arrive at a claim (conclusion). From this point forward, we will refer to this simple relationship as the argument core, and we will diagram the argument core using a “therefore” arrow:

Argument Core: A premise, or set of premises, used to arrive at a conclusion.

Let's look at a quick example of an argument core:

| The sun rises only on Mondays. |  |

The sun does not rise on Fridays. |

We would read this argument core as follows:

The sun rises only on Mondays. THEREFORE, The sun does not rise on Fridays.

In this argument, the premise that the sun rises only on Mondays is used to support the claim that the sun does not rise on Fridays.

Do you think this is a valid argument? Does it make any assumptions? Take a few seconds to think about it before reading on.

Evaluating the Logic of the Core

On Assumption Family questions, your job will be to evaluate the logic of the argument core. When doing so, it's important that you have the right mind-set. Let's look at the argument core again:

| The sun rises only on Mondays. |  |

The sun does not rise on Fridays. |

Here are two ways to think about it:

1. The real-world approach.

“No way! Terrible argument! We all know that the sun rises every day, not just on Mondays.”

2. The logical approach.

“Well, if we take the premise as a given truth, that the sun rises ONLY on Mondays, is this enough to substantiate the claim that the sun does NOT rise on Fridays? Yes. Logically speaking, this argument is sound.”

Now, most likely you haven't been studying for the LSAT for very long, but you've probably figured out that the LSAT folks aren't very interested in testing your ability to make evaluations of whether real-world facts are true or untrue. They are, however, very much interested in testing your ability to evaluate logic, the manner in which elements of an argument connect to one another.

In evaluating an argument, your job is NOT to evaluate the truth of its parts. Your job is to evaluate the logic: does the evidence given validate the conclusion? In this case, it does.

Let's try another one:

| Everyone in the room is wearing a jacket. |  |

Jim must be wearing a jacket. |

Remember, the arrow means “therefore.” We would read this argument core as follows:

Everyone in the room is wearing a jacket. THEREFORE, Jim must be wearing a jacket.

As you evaluate the logic of this argument core, you want to ask yourself if the premise allows you to draw the conclusion without any problems. Does the premise substantiate the conclusion? In this case, it doesn't. In fact, the argument makes a pretty big assumption—it assumes that Jim is one of the people in the room! Notice how the assumption, when inserted into the argument, actually strengthens the argument:

Everyone in the room is wearing a jacket. (Jim is in the room). THEREFORE, Jim must be wearing a jacket.

The assumption functions as a connecting bridge between the premise and the conclusion.

So, to this point, we've seen an argument core that was rock solid, and one that needed an assumption. Almost all LSAT arguments have cores that require an assumption or assumptions in order to be sound. Sometimes the assumption is easy to spot, but other times it's more difficult. You'll get better and better at recognizing and defining these gaps as you continue your study, but here is some advice to get you started.

Beware of Implicit Connections

Tendency #1: Real-world synonymous

LSAT arguments will often include assumed connections between concepts that we generally see as being synonymous in real life. In real life, it is often helpful to focus on how these concepts are similar. However, for the LSAT, it is critical that you pay attention to the differences. Take this, for example:

| Hiroshi always does what is right. |  |

Hiroshi is a moral person. |

This seems to make good sense, doesn't it? If you heard this argument at the dinner table, you wouldn't bat an eye. However, on the LSAT, this argument is flawed. It assumes that doing what is right and being a moral person are equivalent concepts. Don't take this for granted. Let's insert the assumption into the core to see how it strengthens the argument:

Hiroshi always does what is right. (Always doing what is right is the same as being a moral person.) Hiroshi is a moral person.

Ah. Now it's airtight. Remember, real-world synonymous is not necessarily the same as LSAT synonymous.

Tendency #2: Subtle wording changes and modifiers

Sometimes the LSAT will make an implicit connection between two things that are subtly different based on just one word. Try this:

| Great writers always imbue their writing with their own personal experiences. |  |

It's clear, then, that the most popular writers use personal experiences in their stories. |

This may seem like a good argument at first, but notice the difference between “great” in the premise and “the most popular” in the conclusion. To be great, and to be the most popular, are not the same. The argument assumes that the “most popular writers” are “great writers.” Notice how much stronger the argument becomes when we insert this assumption:

Great writers always imbue their writing with their own personal experiences. (The most popular writers are great writers.) It's clear, then, that the most popular writers use personal experiences in their stories.

Beware of Other Paths to the Conclusion

Many LSAT arguments will be faulty because the author will assume that one path to a certain outcome is the only path to that outcome.

Have a look at this one:

| Bert lost 15 pounds last summer. |  |

Bert must have been on a diet last summer. |

Sure, that's one possibility, but are we able to conclude for certain that a diet was the reason for the weight loss? Of course not. Maybe he had a health issue that led to a drop in weight, or maybe he exercised each day over the summer. This argument assumes that nothing else, aside from a diet, could have accounted for Bert's weight loss. Let's insert it:

Bert lost 15 pounds last summer. (Nothing else, aside from a diet, could have contributed to Bert's weight loss.) Bert must have been on a diet last summer.

Much better.

Notice that this assumption helps the argument by eliminating every other possible explanation, but note that some assumptions can help the argument by partially bridging the gap, or by eliminating just one of the alternative possibilities.

Bert lost 15 pounds last summer. (Exercise did not account for Bert's weight loss.) Bert must have been on a diet last summer.

Is this assumption enough on its own to make the argument valid? No, but it's certainly necessary to make the argument valid.

Don't worry at this point if you feel unsure of your ability to spot gaps in the logic. Later on in the chapter, and for the next four chapters, you'll have a chance to work on identifying assumptions. For now, let's move on to discuss the task of finding the argument core.

Identifying the Argument Core

At this point, you've learned about the argument core, and you've had some practice evaluating the logic of the core. This is a crucial skill that you'll need to answer Assumption Family questions. Unfortunately, evaluating the logic of the core is only one piece of the process. Before you can evaluate the logic, you need to correctly identify the core. Sometimes it'll be easy to spot, as it was in the Kennedy/Nixon example from earlier. Kennedy stated a premise…

“I've been there [in Congress] now for fourteen years, the same period of time that he has [referring to Nixon's six years in Congress and eight years as Vice President]…”

and then finished with his conclusion…

“…so that our experience in, uh, government is comparable….”

The LSAT won't always make it this easy on you. Let's discuss some of the challenges that you'll be faced with.

One quick note: we are NOT suggesting you write out argument cores during the LSAT. This mostly will be an internal process.

Organizational Structure

The LSAT will often change the organizational structure (order) of the argument components to make things a bit trickier. Here are two different ways that the same argument can be ordered:

1. PREMISE-CONCLUSION

This is the ordering that Kennedy used in his argument. It's the simplest of the possible orderings:

I will be out of town more this month than I was last month. Thus, my electricity bill will be less this month than it was last month.

[By the way, if you're thinking about the inherent assumptions made in this argument, you're reading like a debater!]

2. CONCLUSION-PREMISE

The LSAT will often construct arguments that place the support after the conclusion:

My electricity bill will be less this month than it was last month because I will be out of town more this month than I was last month.

These two arguments are identical. The thing to notice here is that organizational structure has nothing to do with logical structure. Regardless of how we arrange the pieces, we still have the same argument core:

| out of town more this month than last |  |

electricity bill will be less this month than it was last month |

Getting a handle on an argument's organization becomes more challenging as the argument is lengthened and other parts added. Let's continue this discussion after we've looked at these other argument components.

Background Information

Sometimes you'll see argument components that don't seem like supporting premises or conclusions. Often, the LSAT will include neutral background information in an attempt to orient (or disorient) the reader before the real argument starts. Don't let this confuse you, though. We're still looking for the argument core. Take this one:

Next week, our school board will vote on a proposal to extend the school day by one hour. This proposal will not pass. A very similar proposal was voted down by the school board in a neighboring town.

Here's a breakdown of the argument, point by point:

BACKGROUND: Next week, our school board will vote on a proposal to extend the school day by one hour.

CONCLUSION: This proposal will not pass.

SUPPORTING PREMISE: A very similar proposal was voted down by the school board in a neighboring town.

Maybe you correctly identified the conclusion, but had trouble figuring out which sentence, the first or the last, was the supporting premise. When this happens, identify the conclusion and then ask “Why?” The proposal will not pass. Okay, why does the author believe this? Is it because the board will vote on the proposal? No. Is it because a similar proposal failed in a nearby town? Ah, yes. This must be the supporting premise.

When looking for the argument core, you want to consider just the premise  conclusion relationship:

conclusion relationship:

| similar proposal voted down in nearby town |  |

proposal will not pass |

The rest of the information is background information to provide context for the argument core. Context is important, but remember that it's only there to help you understand the core.

Intermediate Conclusions and the Therefore Test

A chain of logic will often contain an intermediate conclusion that supports the final conclusion. This adds further complexity. Take a look at the example below. Notice anything different?

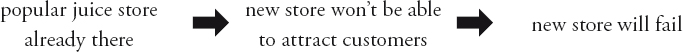

A new lemonade stand has just opened for business in the town square. The stand will surely fail. A popular juice store already sells lemonade in the town square, so the new lemonade stand will not be able to attract customers.

You can see that as more and more complicating elements are added in, the argument core becomes more difficult to track. In this case, there seem to be two possible conclusions, or opinions: (1) the stand will surely fail, or (2) the new lemonade stand will not be able to attract customers. Remember, before you can answer any question related to such an argument, you MUST know what the main point, or final conclusion, is. There can be only one. Let's use what we call “The Therefore Test” to identify the final conclusion. We'll propose two possible P  C relationships between our two candidates:

C relationships between our two candidates:

Case #1: The new lemonade stand will surely fail. THEREFORE, the new lemonade stand will not be able to attract customers.

Case #2: The new lemonade stand will not be able to attract customers. THEREFORE, the new lemonade stand will surely fail.

The first case doesn't make a whole lot of sense. In the second case, however, the first part of the statement clearly supports, or leads into, the second part of the statement. Because the stand will not be able to attract customers, it will surely fail. (If you're having trouble, try thinking about it in terms of chronology—what happens first? The stand doesn't attract new customers, and this leads to the failure of the stand.) Thus, the final conclusion, the main conclusion, is that “The stand will surely fail.” Any conclusion that supports the final conclusion is called an intermediate conclusion. Intermediate conclusions are always supported by a premise.

Let's break this argument down:

BACKGROUND: A new lemonade stand has just opened for business in the town square.

CONCLUSION (final opinion): The stand will surely fail.

SUPPORTING PREMISE (fact): A popular juice store already sells lemonade in the town square,

INTERMEDIATE CONCLUSION (opinion): so the new lemonade stand will not be able to attract customers.

Here it is in argument core form: (P) premise  (IC) intermediate conclusion

(IC) intermediate conclusion  (C) conclusion.

(C) conclusion.

Notice that we actually have two embedded arguments in this complex core: (1) P  IC, and (2) IC

IC, and (2) IC  C. In the context of the real exam, we would need to evaluate both arguments for potential issues. However, the LSAT tends to base questions on the gap between the intermediate conclusion and the final conclusion.

C. In the context of the real exam, we would need to evaluate both arguments for potential issues. However, the LSAT tends to base questions on the gap between the intermediate conclusion and the final conclusion.

Opposing Points

Think about the arguments that you make on a daily basis (you probably make more than you realize). Sometimes you can add to your argument by conceding a point or two to the other side. In doing so, you show that you've considered alternate viewpoints, and you also steal the thunder of the person who might be arguing against you! The LSAT does this all the time. Let's revisit the lemonade argument with an added twist:

A new lemonade stand has just opened for business in the town square. The price per cup at the new stand is the lowest in town, but the store will surely fail. A popular juice store already sells lemonade in the town square, so the new lemonade stand will not be able to attract customers.

In this case, the fact that “the price per cup at the new stand is the lowest in town” is an opposing point; it is a counter premise that would seem to support the opposite claim (that the lemonade stand will NOT fail). Notice that the contrast with the main conclusion is set up with the word “but.” Here's another, slightly different example:

A new lemonade stand has just opened for business in the town square. The columnist in the local paper writes that the stand will succeed, but it will surely fail. A popular juice store already sells lemonade in the town square, so the new lemonade stand will not be able to attract customers.

Notice again the contrast word “but.” In this case, the opposing point (“the columnist in the local paper writes that the stand will succeed”) is actually a counterclaim. It is directly opposed to the claim made by the author (that the stand will surely fail).

Again, the LSAT often uses opposing points to add more texture (and confusion!) to a passage. Some opposing points are counter premises, others are counterclaims. Regardless, it'll be important that you separate the opposing points from the elements of the argument core. Don't confuse the sides! In this case, the argument core is still:

Multiple Premises

The LSAT often presents arguments that seem to contain multiple premises. In these cases, it can be difficult to figure out what the real core of the argument is. There are a few ways that the LSAT structures multiple-premise arguments.

1. Complementary Premises

Last year, Karina spent 20% of her income on rent. This year, she spent 30% of her income on rent. Thus, Karina spent more money on rent this year than last year.

Here's a breakdown of the argument structure:

SUPPORTING PREMISE: Last year, Karina spent 20% of her income on rent.

SUPPORTING PREMISE: This year, she spent 30% of her income on rent.

CONCLUSION: Thus, Karina spent more money on rent this year than last year.

Notice that the author uses the two premises in a complementary way in order to arrive at the conclusion. One premise is no more important than the other, and both are needed to arrive at the conclusion. One way to tell that both premises are going to be important is to notice that the conclusion makes a relative comparison between two things (money spent on rent last year vs. money spent on rent this year). In a case like this where such a relative comparison is made, supporting information generally comes from two premises (in this case, one stating a fact about last year and one stating a fact about this year). We can think of the argument core as follows: P + P  C:

C:

| last year 20% on rent + this year 30% on rent |

|

more rent money spent this year |

(By the way, are you seeing the issue with this argument? What assumption is made? Hint: I spend 50% of my income on rent. Donald Trump spends 40% of his income on rent. Therefore, I spend more money on rent than Donald Trump does. Hmmm.)

2. Duplicate Premises

In recent years, global sales of so-called “smartphones” have skyrocketed. In increasing numbers, people from all over the world are purchasing devices that have the capability to play music, snap photos, surf the internet, and receive incoming phone calls. It must be the case that smartphone manufacturers are making huge profits.

Here's a breakdown of the argument structure:

SUPPORTING PREMISE: In recent years, global sales of so-called “smartphones” have skyrocketed.

SUPPORTING PREMISE: In increasing numbers, people from all over the world are purchasing devices that have the capability to play music, snap photos, surf the internet, and receive an incoming phone call.

CONCLUSION: It must be the case that smartphone manufacturers are making huge profits.

Wow. Lots of information! How do we know what the argument core is? Should we use the first premise or the second? Maybe the two premises complement each other as in the example we saw previously? Look closely and note that the two supporting premises actually say the same thing in slightly different words. From a logical perspective, the premises are duplicates, not complements. In essence, the argument core is this:

| increasing sales of smart phones |  |

manufacturers must be making huge profits |

(Again, be sure you're thinking about the assumption that is made in this argument. Are sales figures the only important factor in determining profit levels?)

Here's another, slightly different example:

Some people claim that a low-carbohydrate diet is essential to maintaining a healthy body weight. This is simply not true. Many Europeans regularly eat foods that are very high in carbohydrates. Italians, for instance, eat lots of breads and pastas.

What's the conclusion? What's the supporting premise? Think about it before reading on.

OPPOSING POINT: Some people claim that a low-carbohydrate diet is essential to maintaining a healthy body weight.

CONCLUSION: This is simply not true.

SUPPORTING PREMISE: Many Europeans regularly eat foods very high in carbohydrates.

SUPPORTING PREMISE: Italians, for instance, eat lots of breads and pastas.

Okay, so we have the conclusion, but what's the premise that supports this conclusion? Both of the premises seem to support the conclusion, but note that the second premise is simply an example of the first! The second premise doesn't really say the same thing (it's more detailed), but it doesn't add any crucial additional information. Our core would simply be:

| many Europeans eat lots of carbs |  |

low-carb diet NOT essential to maintaining healthy body weight |

(What is this argument assuming about Europeans? It assumes that they maintain a healthy body weight!)

Borrowed Language

Take another look at the argument core above. Notice that we reworded the conclusion from “this claim is simply not true” to “low-carb diet NOT essential to maintaining healthy body weight.” The LSAT will often try to make things difficult on you by using borrowed language to hide or disguise the argument core. It sounds complicated, but it's really not. If you know your English grammar rules, you're already familiar with the concept of borrowing information from other parts of the sentence or from other sentences. Here's an example:

Jack spends his Saturday afternoons driving his Porsche on the mountain roads. He loves doing that.

This short paragraph has two sentences. The second sentence borrows information from the first. “He” borrows the “Jack” from the first sentence, and “that” borrows the “driving his Porsche on the mountain roads” from the first sentence.

In Logical Reasoning arguments, premises and conclusions sometimes borrow information from other parts of the passage. When this happens, it's easy to get things confused and end up with a misinterpretation of the core. Take this simple example:

Some doctors recommend taking aspirin to relieve the symptoms of a fever. This is bad advice. A fever is part of the body's natural defense against illness.

Here's a breakdown of the argument structure:

OPPOSING POINT: Some doctors recommend taking aspirin to relieve the symptoms of a fever.

CONCLUSION: This is bad advice.

SUPPORTING PREMISE: A fever is part of the body's natural defense against illness.

The core of the argument is:

| fever part of body's natural defense against illness |  |

this is bad advice |

Hmm. Read that again. Taken on its own, this argument core makes no sense because we don't know what “this” is. What is bad advice? Here, the conclusion borrows language from the opposing point! “This” refers to the recommendation to take aspirin to relieve the symptoms of a fever. In order to correctly analyze the logic of the core, we need to know exactly what that advice is. Thus, when we consider the core argument, we need to consider it as follows:

| fever part of body's natural defense against illness |  |

shouldn't take aspirin to relieve symptoms of a fever |

Now we're in a position to evaluate the logic of this core. Does the premise validate the conclusion? Are any assumptions made? Yes. For one, the argument assumes that relieving the symptoms of a fever hinders the fever's ability to provide defense against illness.

Here's another, more difficult example of language borrowing:

Teacher: Many of our students think that the earth is further from the sun in the winter than in the summer. This erroneous thinking shows that our science curriculum has not been effective.

What's the core of the argument? Go ahead and think about it for a moment before reading on.

It's very difficult to classify the parts of this passage. We always need to start by finding the conclusion, and in this case we can use a word/phrase cue to help us. The phrase “This…shows that…” is the same as saying, “this demonstrates X” or “this supports X.” So, the conclusion will likely be the X. This is the main point, or primary opinion of the argument:

CONCLUSION: Our science curriculum has not been effective.

Now we need to ask ourselves “why?” What supports this claim? Well, “This erroneous thinking” shows that the science curriculum has failed. What is “this erroneous thinking?” The word “this” borrows information from the first sentence. The erroneous thinking is believing that the earth is further from the sun in the winter. We have the conclusion, and we now have the supporting premise, so we've got our core:

| students erroneously believe earth is further from sun in winter |  |

our science curriculum has not been effective |

We've covered a host of issues that increase the challenge when it comes to identifying the argument core. Most of the information above is meant to illuminate common patterns and argument structures so that you can more easily identify the pieces of the text that matter most. In this last example, we used a language cue (“this shows that”) in order to help us find the core. Let's take a closer look at language cues.

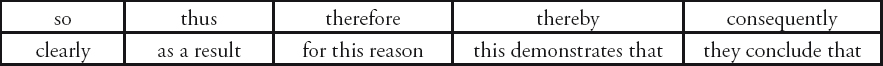

Language Cues

The English language is full of cue words or phrases that are designed to serve as signposts for the listener or reader. Below, we will list the most common of these cues. That said, please note that the LSAT is on to you. They know that when you see the word “thus” you will automatically be thinking “conclusion!” Sometimes, the LSAT will attempt to fool you. All of this is to say that these cues are good helpers, but they are tendencies, NOT absolutes. Below are four language cues:

1. Conclusion Cues. The following words or phrases typically (not always) are indicators of opinions or claims. The LSAT will often use them to introduce a conclusion or an intermediate conclusion:

2. Supporting Premise Cues. The LSAT will often use the following words or phrases to introduce a supporting premise:

| since | because |

| the reason is | for (as in, “…for he's a jolly-good fellow”) |

3. Opposing Point Cues. Opposing points often come at the start of an Logical Reasoning passage, and they are commonly introduced with the following type of language:

| Some believe that | Some say that |

| Most people claim that | Experts have asserted that |

4. Transition Cues. Transition, or pivot, words are extremely common on the exam. They are used to indicate a change in direction, or a change in opinion (usually from an opposing point to a supporting premise or the main conclusion). Some common transition words and phrases are:

Here's an example chock-full of language cues:

Some of my friends say that skiing is the best way to burn calories, but this is ridiculous. Since the act of skiing down a mountain is primarily driven by the pull of gravity, skiing requires very little physical exertion. Thus, skiing doesn't burn many calories.

We start off with an opposing point (“Some of my friends say…”), and then we encounter a big transition word (“but”) that indicates a change in direction. Sure enough, we get the author's opinion/conclusion next (“this is ridiculous”). The word “this” serves to borrow language from the opposing point. “This” refers to the claim that skiing is the best way to burn calories. Essentially, the author is saying “skiing is NOT the best way to burn calories.” At this point, we should expect some supporting reasoning. We encounter a supporting premise cue (“since”), which leads into the supporting fact: gravity is the primary driver. What does it support? It supports the intermediate conclusion (“skiing requires very little physical exertion”). Then we get a fake-out “thus!” In this case, “skiing requires very little physical exertion” supports the intermediate conclusion that “skiing doesn't burn many calories,” which supports the final conclusion that skiing is NOT the best way to burn calories. Watch out for the fake-out “thus!” So, here's the argument core: P  IC

IC  IC

IC  C:

C:

DRILL IT: Identifying the Argument Core

Identify the argument core for each of the passages given below. For the purposes of this exercise, take the time to write the core, in arrow form, on your paper. Be sure to check your answers against the solutions we've given (check your answer after each question so that you can learn from your mistakes before attempting the next one). Your paraphrases may not always be identical to ours—that's okay. Just make sure the general P  C relationship is the same.

C relationship is the same.

The first 10 arguments are of average LSAT difficulty. The final 5 arguments come from questions of high difficulty. “PT, S, Q” refers to the LSAT PrepTest from which the question was taken, the section of that PrepTest, and the question number.

1. PT7, S1, Q10

A large group of hyperactive children whose regular diets included food containing large amounts of additives was observed by researchers trained to assess the presence or absence of behavior problems. The children were then placed on a low additive diet for several weeks, after which they were observed again. Originally nearly 60 percent of the children exhibited behavior problems; after the change in diet, only 30 percent did so. On the basis of these data, it can be concluded that food additives can contribute to behavior problems in hyperactive children.

2. PT7, S1, Q20

According to sources who can be expected to know, Dr. Maria Esposito is going to run in the mayoral election. But if Dr. Esposito runs, Jerome Krasman will certainly not run against her. Therefore Dr. Esposito will be the only candidate in the election.

3. PT7, S4, Q1

In 1974 the speed limit on highways in the United States was reduced to 55 miles per hour in order to save fuel. In the first 12 months after the change, the rate of highway fatalities dropped 15 percent, the sharpest one year drop in history. Over the next 10 years, the fatality rate declined by another 25 percent. It follows that the 1974 reduction in the speed limit saved many lives.

4. PT7, S4, Q2

Some legislators refuse to commit public funds for new scientific research if they cannot be assured that the research will contribute to the public welfare. Such a position ignores the lessons of experience. Many important contributions to the public welfare that resulted from scientific research were never predicted as potential outcomes of that research. Suppose that a scientist in the early twentieth century had applied for public funds to study molds: who would have predicted that such research would lead to the discovery of antibiotics—one of the greatest contributions ever made to the public welfare?

5. PT7, S4, Q3

When workers do not find their assignments challenging, they become bored and so achieve less than their abilities would allow. On the other hand, when workers find their assignments too difficult, they give up and so again achieve less than what they are capable of achieving. It is, therefore, clear that no worker's full potential will ever be realized.

6. PT7, S4, Q13

The National Association of Fire Fighters says that 45 percent of homes now have smoke detectors, whereas only 30 percent of homes had them 10 years ago. This makes early detection of house fires no more likely, however, because over half of the domestic smoke detectors are either without batteries or else inoperative for some other reason.

7. PT7, S4, Q20

Graphologists claim that it is possible to detect permanent character traits by examining people's handwriting. For example, a strong cross on the “t” is supposed to denote enthusiasm. Obviously, however, with practice and perseverance people can alter their handwriting to include this feature. So it seems that graphologists must hold that permanent character traits can be changed.

8. PT9, S2, Q7

Waste management companies, which collect waste for disposal in landfills and incineration plants, report that disposable plastics make up an ever-increasing percentage of the waste they handle. It is clear that attempts to decrease the amount of plastic that people throw away in the garbage are failing.

9. PT9, S2, Q1

Crimes in which handguns are used are more likely than other crimes to result in fatalities. However, the majority of crimes in which handguns are used do not result in fatalities. Therefore, there is no need to enact laws that address crimes involving handguns as distinct from other crimes.

10. PT9, S2, Q4

Data from satellite photographs of the tropical rain forest in Melonia show that last year the deforestation rate of this environmentally sensitive zone was significantly lower than in previous years. The Melonian government, which spent millions of dollars last year to enforce laws against burning and cutting of the forest, is claiming that the satellite data indicate that its increased efforts to halt the destruction are proving effective.

11. PT7, S1, Q24

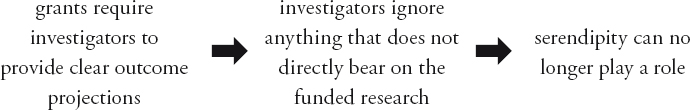

Many major scientific discoveries of the past were the product of serendipity, the chance discovery of valuable findings that investigators had not purposely sought. Now, however, scientific research tends to be so costly that investigators are heavily dependent on large grants to fund their research. Because such grants require investigators to provide the grant sponsors with clear projections of the outcome of the proposed research, investigators ignore anything that does not directly bear on the funded research. Therefore, under the prevailing circumstances, serendipity can no longer play a role in scientific discovery.

12. PT7, S1, Q7

Coherent solutions for the problem of reducing health care costs cannot be found within the current piecemeal system of paying these costs. The reason is that this system gives health care providers and insurers every incentive to shift, wherever possible, the costs of treating illness onto each other or any other party, including the patient. That clearly is the lesson of the various reforms of the 1980s: push in on one part of this pliable spending balloon and an equally expensive bulge pops up elsewhere. For example, when the government health care insurance program for the poor cut costs by disallowing payments for some visits to physicians, patients with advanced illness later presented themselves at hospital emergency rooms in increased numbers.

13. PT7, S4, Q8

George: Some scientists say that global warming will occur because people are releasing large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere by burning trees and fossil fuels. We can see, though, that the predicted warming is occurring already. In the middle of last winter, we had a month of springlike weather in our area, and this fall, because of unusually mild temperatures, the leaves on our town's trees were three weeks late in turning color.

14. PT9, S2, Q19

A university should not be entitled to patent the inventions of its faculty members. Universities, as guarantors of intellectual freedom, should encourage the free flow of ideas and the general dissemination of knowledge. Yet a university that retains the right to patent the inventions of its faculty members has a motive to suppress information about a potentially valuable discovery until the patent for it has been secured. Clearly, suppressing information concerning such discoveries is incompatible with the university's obligation to promote the free flow of ideas.

15. PT9, S2, Q3

Balance is particularly important when reporting the background of civil wars and conflicts.

Facts must not be deliberately manipulated to show one party in a favorable light, and the views of each side should be fairly represented. This concept of balance, however, does not justify concealing or glossing over basic injustices in an effort to be even-handed. If all the media were to adopt such a perverse interpretation of balanced reporting, the public would be given a picture of a world where each party in every conflict had an equal measure of justice on its side, contrary to our experience of life and, indeed, our common sense.

SOLUTIONS: Identifying the Argument Core

The solutions below will demonstrate the real-time thought process for finding the argument core. All comments in italics represent the thoughts of the test-taker.

1. PT7, S1, Q10

A large group of hyperactive children whose regular diets included food containing large amounts of additives was observed by researchers trained to assess the presence or absence of behavior problems.

Definitely background information. This is setting us up to receive research findings of some kind.

The children were then placed on a low additive diet for several weeks, after which they were observed again.

More setup. (By the way, this is very common on arguments that make conclusions from research studies. They generally start by giving background information on the way the study was administered.)

Originally nearly 60 percent of the children exhibited behavior problems;

One of the findings from the study.

after the change in diet, only 30 percent did so.

The other finding from the study. I bet the next part will use both of these findings, or premises, to draw a conclusion.

On the basis of these data, it can be concluded that food additives can contribute to behavior problems in hyperactive children.

“On the basis of these data….” Okay, so these two data points (complementary premises) are being used to support the conclusion.

| 60% originally had behavior problems + 30% had behavior problems after decreasing additives in diet |

|

food additives can contribute to behavior problems in hyperactive children |

2. PT7, S1, Q20

According to sources who can be expected to know, Dr. Maria Esposito is going to run in the mayoral election. But if Dr. Esposito runs, Jerome Krasman will certainly not run against her. Therefore Dr. Esposito will be the only candidate in the election.

Pretty straightforward argument with two complementary premises and an easy-to-spot conclusion:

| if Esposito runs, Krasman will not + Esposito will run |

|

Esposito will be only candidate in race |

3. PT7, S4, Q1

In 1974 the speed limit on highways in the United States was reduced to 55 miles per hour in order to save fuel.

This is a historical fact. It's probably just background information.

In the first 12 months after the change, the rate of highway fatalities dropped 15 percent, the sharpest one year drop in history.

This feels like it's going to be support for something. (Statistics will generally be used as supporting evidence.)

Over the next 10 years, the fatality rate declined by another 25 percent.

Another statistic. These two stats will probably complement each other to come up with a final claim.

It follows that the 1974 reduction in the speed limit saved many lives.

And there's the claim. The core of the argument is:

| in first year after reduction, 15% drop in deaths + another 25% drop over next 10 years |

|

reduction has saved many lives |

4. PT7, S4, Q2

Some legislators refuse to commit public funds for new scientific research if they cannot be assured that the research will contribute to the public welfare.

“Some legislators….” This has the tone of an opposing point that is about to be countered.

Such a position ignores the lessons of experience.

This seems to be the main conclusion, a counter to the legislators view above. “Such a position” borrows language from the first sentence. The author is claiming that the legislators’ refusal to commit public funds because of a lack of assurance of results is a position that ignores the lessons of experience. You can anticipate that the “lessons of experience” are forthcoming!

Many important contributions to the public welfare that resulted from scientific research were never predicted as potential outcomes of that research.

And here's the support—lessons of experience.

Suppose that a scientist in the early twentieth century had applied for public funds to study molds: who would have predicted that such research would lead to the discovery of antibiotics—one of the greatest contributions ever made to the public welfare?

Lots of information here, but it's duplicate information. It's a specific example of the premise above, an example of a case in which contributions to the public welfare (discovery of antibiotics) were not predicted. The core is:

| many important contributions came from research but were never predicted as potential outcomes |  |

legislators’ position to refuse to commit to research unless outcomes are assured is a position that ignores lessons of experience |

5. PT7, S4, Q3

When workers do not find their assignments challenging, they become bored and so achieve less than their abilities would allow. On the other hand, when workers find their assignments too difficult, they give up and so again achieve less than what they are capable of achieving. It is, therefore, clear that no worker's full potential will ever be realized.

Straightforward argument that uses two complementary premises to arrive at an easy-to-spot conclusion:

| workers underachieve when assignments are not challenging enough + workers underachieve when assignments are too challenging |

|

no worker's full potential will ever be realized |

6. PT7, S4, Q13

The National Association of Fire Fighters says that 45 percent of homes now have smoke detectors, whereas only 30 percent of homes had them 10 years ago.

“The National Association of Fire Fighters says….” Seems like it'll be opposing information of some sort.

This makes early detection of house fires no more likely, however,

The word “however” indicates a pivot, or transition away from the first sentence. The information given by the fire fighters, that more homes now have detectors, would seem to indicate that detection of home fires WOULD be more likely, but the author is saying that the detection of fires would NOT be any more likely. Is this the author's conclusion, or is it just a fact being used for something else?

because over half of the domestic smoke detectors are either without batteries or else inoperative for some other reason.

“Because” indicates that this is support for the author's claim above. The core is:

| over half of domestic detectors are without batteries or are inoperative |  |

increase in detectors from 30% to 45% does not make home fires any less likely |

7. PT7, S4, Q20

Graphologists claim that it is possible to detect permanent character traits by examining people's handwriting.

This sort of opposing point (“Graphologists claim…”) is starting to get easy to recognize!

For example, a strong cross on the “t” is supposed to denote enthusiasm.

Simply an example to help explain the graphologists’ claim.

Obviously, however, with practice and perseverance people can alter their handwriting to include this feature.

The word “however” indicates that this statement counters the graphologists’ claim. Is this the final claim or just a factual statement that will support something else? Hard to tell for now.

So it seems that graphologists must hold that permanent character traits can be changed.

Ah. The word “so” indicates that this is the main conclusion, and the part before is simply support for this conclusion.

| people can change their handwriting characteristics |  |

graphologists must hold that people can change their permanent character traits |

8. PT9, S2, Q7

Waste management companies, which collect waste for disposal in landfills and incineration plants, report that disposable plastics make up an ever-increasing percentage of the waste they handle.

“Waste management companies report…” This seems to be another example of an opposing point that will be refuted or countered somehow.

It is clear that attempts to decrease the amount of plastic that people throw away in the garbage are failing.

Oh, wait. We get no counter point. In fact, “it is clear” indicates that this is the conclusion. The waste management companies’ reports are actually meant to serve as support for the conclusion.

| waste management reports increasing percentage of disposable plastics for disposal in landfills and incinerators |  |

attempts to decrease amount of plastic people throw away in garbage are failing |

9. PT9, S2, Q1

Crimes in which handguns are used are more likely than other crimes to result in fatalities.

Seems like a statement of fact. Hard to say exactly how it will function at this point.

However, the majority of crimes in which handguns are used do not result in fatalities.

This is tricky. The “however” doesn't seem to refute the first statement. It just introduces a related fact.

Therefore, there is no need to enact laws that address crimes involving handguns as distinct from other crimes.

This is obviously the conclusion, and now we can see that the two points made earlier ARE in fact in opposition to each other. The conclusion is that we don't need laws for handgun crimes in particular. The first statement (that handgun crimes are more likely to result in deaths) would seem to suggest that we DO need special laws, but the second statement (the majority of handgun crimes do not result in deaths) would be evidence to suggest that we DON'T need the special laws. So, the second statement supports the conclusion:

| most crimes in which handguns are used do not result in deaths |  |

no need to enact special laws for crimes involving handguns |

10. PT9, S2, Q4

Data from satellite photographs of the tropical rain forest in Melonia show that last year the deforestation rate of this environmentally sensitive zone was significantly lower than in previous years.

Factual information. Maybe just background information? Hard to say just yet.

The Melonian government, which spent millions of dollars last year to enforce laws against burning and cutting of the forest,

Another fact. The government spent millions of dollars to stop burning and cutting of forests.

[The Melonian Government] is claiming that the satellite data indicate that its increased efforts to halt the destruction are proving effective.

The conclusion! The word “claiming” gives it away. Notice that the conclusion ties together information about the deforestation rate and the efforts made by the government to curb burning and cutting. This is a case where two complementary premises are used to support the final claim:

| deforestation rate decreasing + government spent millions to curb cutting and burning |

|

government efforts are proving effective |

11. PT7, S1, Q24

Many major scientific discoveries of the past were the product of serendipity, the chance discovery of valuable findings that investigators had not purposely sought.

Statement of fact. Not yet sure how it will be used.

Now, however, scientific research tends to be so costly that investigators are heavily dependent on large grants to fund their research.

Another statement of fact that provides a contrast between then and now.

Because such grants require investigators to provide the grant sponsors with clear projections of the outcome of the proposed research,

“Because” indicates support for something, and that something must be coming up…

investigators ignore anything that does not directly bear on the funded research.

Could this be the final claim, then?

Therefore, under the prevailing circumstances, serendipity can no longer play a role in scientific discovery.

Ah. This is the final claim. So we actually have a three-part argument core with an intermediate conclusion in the middle:

12. PT7, S1, Q7

Coherent solutions for the problem of reducing health care costs cannot be found within the current piecemeal system of paying these costs.

This sounds like an opinion. Could it be the final conclusion?

The reason is that this system gives health care providers and insurers every incentive to shift, wherever possible, the costs of treating illness onto each other or any other party, including the patient.

“The reason is that…” is a big language cue. This must be support for the first sentence! So, it seems we got the conclusion first, immediately followed by a supporting premise.

That clearly is the lesson of the various reforms of the 1980s: push in on one part of this pliable spending balloon and an equally expensive bulge pops up elsewhere. For example, when the government health care insurance program for the poor cut costs by disallowing payments for some visits to physicians, patients with advanced illness later presented themselves at hospital emergency rooms in increased numbers.

Wow, lots of information, but all of this is simply illustrating, or providing an example of, the shifting costs described in the premise above it. We can think of all this as duplicate information. Our core is:

| system gives incentive to shift costs to others |  |

solutions for reducing costs cannot be found in current system |

13. PT7, S4, Q8

George: Some scientists say that global warming will occur because people are releasing large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere by burning trees and fossil fuels.

“Some scientists say….” Sounds like an opposing point that's about to be refuted!

We can see, though, that the predicted warming is occurring already.

Yes, “though” provides a transition into the author's claim: the warming is happening already. You can anticipate that you'll get some support for this next.

In the middle of last winter, we had a month of springlike weather in our area,

One piece of evidence to support the claim that the warming is already happening.

and this fall, because of unusually mild temperatures, the leaves on our town's trees were three weeks late in turning color.

And another piece of complementary evidence. Two premises support the author's claim:

| springlike weather in winter + mild fall weather delayed color change on leaves |

|

predicted warming already happening |

14. PT9, S2, Q19

A university should not be entitled to patent the inventions of its faculty members.

Strong opinion. Could be the conclusion.

Universities, as guarantors of intellectual freedom, should encourage the free flow of ideas and the general dissemination of knowledge.

Another opinion that seems to support the first!

Yet a university that retains the right to patent the inventions of its faculty members has a motive to suppress information about a potentially valuable discovery until the patent for it has been secured.

Tricky. The word “yet” seems to indicate that a change in direction/opinion is afoot, but this statement actually seems to support the notion that universities shouldn't be allowed to patent inventions. There's not really any transition here at all.

Clearly, suppressing information concerning such discoveries is incompatible with the university's obligation to promote the free flow of ideas.

This seems to be more support for the first statement. The core is complex. It uses three pieces of complementary information to support its final claim:

| universities should promote free flow and dissemination of ideas + universities with right to patent have incentive to suppress information + suppressing information is incompatible with obligation to promote free flow of ideas |

|

university should not be entitled to patent inventions by faculty |

15. PT9, S2, Q3

Balance is particularly important when reporting the background of civil wars and conflicts.

Seems like an opinion. Could it be the conclusion?

Facts must not be deliberately manipulated to show one party in a favorable light, and the views of each side should be fairly represented.

This seems like a duplicate claim! It's really just saying that balance is important.

This concept of balance, however, does not justify concealing or glossing over basic injustices in an effort to be even-handed.

Oh. This is a transition. Okay, balance is important, but not important enough to conceal injustices. Now this feels like the conclusion. Will it get support?

If all the media were to adopt such a perverse interpretation of balanced reporting, the public would be given a picture of a world where each party in every conflict had an equal measure of justice on its side, contrary to our experience of life and, indeed, our common sense.

Yes, this is a reason why we can't have balance trumping everything else. This is the support.

| if all media were to adopt balanced reporting, public would be given inaccurate representation of justice |  |

concept of balance does not justify concealing injustices |

Putting It All Together

You've learned how to read like a debater. You know that your purpose on Assumption Family questions is to identify the argument core. You know that the core of the argument will require assumptions and that it's your job to uncover these assumptions. Now, let's put it all together by revisiting the five questions you tried at the start of the chapter.

Before reviewing the solution, try each question again, giving yourself 1:30. Then check your work against our solution before moving on to the next question.

PT7, S4, Q5

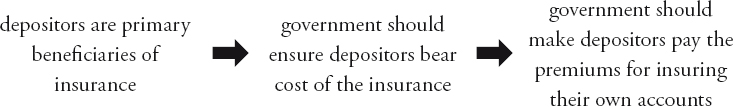

The government provides insurance for individuals’ bank deposits, but requires the banks to pay the premiums for this insurance. Since it is depositors who primarily benefit from the security this insurance provides, the government should take steps to ensure that depositors who want this security bear the cost of it and thus should make depositors pay the premiums for insuring their own accounts.

Which one of the following principles, if established, would do most to justify drawing the conclusion of the argument on the basis of the reasons offered in its support?

(A) The people who stand to benefit from an economic service should always be made to bear the costs of that service.

(B) Any rational system of insurance must base the size of premiums on the degree of risk involved.

(C) Government backed security for investors, such as bank depositors, should be provided only when it does not reduce incentives for investors to make responsible investments.

(D) The choice of not accepting an offered service should always be available, even if there is no charge for the service.

(E) The government should avoid any actions that might alter the behavior of corporations and individuals in the market.

1. The question stem.

Which one of the following principles, if established, would do most to justify drawing the conclusion of the argument on the basis of the reasons offered in its support?

This question asks us to choose a principle that would justify the conclusion. As we'll learn later, this is essentially the same as choosing an assumption to bridge the gap between the premises and the conclusion. This is an Assumption Family question. Thus, we need to find the argument core.

2. The argument.

The government provides insurance for individuals’ bank deposits, but requires the banks to pay the premiums for this insurance.

This is a statement of fact, probably background information or a supporting premise.

Since it is depositors who primarily benefit from the security this insurance provides,

“Since” indicates supporting premise. So, what is it supporting?

the government should take steps to ensure that depositors who want this security bear the cost of it

Okay, so this is supported by the “since” statement, but there's still some passage left to be read…

and thus should make depositors pay the premiums for insuring their own accounts.

This seems like the final claim. The “and thus” seems to indicate that this is being supported by the point made just before it. We have a three-part core with an intermediate conclusion:

(Again, note that this is NOT something we would suggest writing out as you are taking the exam.)

We can prepare for the answer choices by attempting to spot any obvious assumptions made in the argument core. In this case, because we have a three-part core, we have two relationships to analyze:

| depositors are primary beneficiaries of insurance |  |

government should ensure depositors bear cost of the insurance |

Do you see the assumption? Think about it for a second.

This part of the argument assumes that the government should ensure that those who receive the benefits actually pay for the benefits. The second relationship is:

| government should ensure depositors bear cost of the insurance |  |

government should make depositors pay the premiums for insuring their own accounts |

This assumes that if the government needs to ensure that the depositors bear the cost, it should do so by making the depositors pay premiums. What about other ways of ensuring they bear the cost?

Okay, maybe there are other assumptions made, but the LSAT is a timed test! At this point we're ready to take a look at the answer choices. We need to keep in mind that the assumptions we've identified may not actually come up in the choices. Regardless, we've narrowed our focus and we understand how the argument core is working, so we'll be ready to spot an answer that addresses the core.

3. The answer choices.

Remember that we're looking for a general principle that will support the argument. Again, this is another way of saying we're looking for an assumption that will support the argument.

(A) The people who stand to benefit from an economic service should always be made to bear the costs of that service.

This answer is a pretty close match with the assumption we spotted: the government should ensure that those who receive the benefits actually pay for the benefits. Let's keep this for now.

(B) Any rational system of insurance must base the size of premiums on the degree of risk involved.

The core of this argument has nothing to do with how to assess the size of premiums, but rather whether the investors should be forced to pay the premiums. Eliminate this.

(C) Government backed security for investors, such as bank depositors, should be provided only when it does not reduce incentives for investors to make responsible investments.

The core of this argument has nothing to do with determining when to provide insurance to investors, but rather whether the government should force the investors to bear the cost. Eliminate this.

(D) The choice of not accepting an offered service should always be available, even if there is no charge for the service.

The core of this argument has nothing to do with offering a choice for a service, but rather who should pay for that service (in this case, who should pay for the insurance). Get rid of this.

(E) The government should avoid any actions that might alter the behavior of corporations and individuals in the market.