Getting Familiar

To start, go ahead and try these four Identify the Flaw questions. Give yourself no more than six minutes total. We'll revisit these questions later on in the chapter.

PT36, S1, Q12

The consumer price index is a measure that detects monthly changes in the retail prices of goods and services. The payment of some government retirement benefits is based on the consumer price index so that those benefits reflect the change in the cost of living as the index changes. However, the consumer price index does not consider technological innovations that may drastically reduce the cost of producing some goods. Therefore, the value of government benefits is sometimes greater than is warranted by the true change in costs.

The reasoning in the argument is most vulnerable to the criticism that the argument

(A) fails to consider the possibility that there are years in which there is no change in the consumer price index

(B) fails to make explicit which goods and services are included in the consumer price index

(C) presumes, without providing warrant, that retirement benefits are not generally used to purchase unusual goods

(D) uncritically draws an inference from what has been true in the past to what will be true in the future

(E) makes an irrelevant shift from discussing retail prices to discussing production costs

PT14, S2, Q22

Gallery owner: Because this painting appears in no catalog of van Gogh's work, we cannot guarantee that he painted it. But consider: the subject is one he painted often, and experts agree that in his later paintings van Gogh invariably used just such broad brushstrokes and distinctive combinations of colors as we find here. Internal evidence, therefore, makes it virtually certain that this is a previously uncataloged, late van Gogh, and as such, a bargain at its price.

The reasoning used by the gallery owner is flawed because it

(A) ignores the fact that there can be general agreement that something is the case without its being the case

(B) neglects to cite expert authority to substantiate the claim about the subject matter of the painting

(C) assumes without sufficient warrant that the only reason anyone would want to acquire a painting is to make a profit

(D) provides no evidence that the painting is more likely to be an uncataloged van Gogh than to be a painting by someone else who painted that particular subject in van Gogh's style

(E) attempts to establish a particular conclusion because doing so is in the reasoner's self interest rather than because of any genuine concern for the truth of the matter

PT34, S2, Q9

A university study reported that between 1975 and 1983 the length of the average workweek in a certain country increased significantly. A governmental study, on the other hand, shows a significant decline in the length of the average workweek for the same period. Examination of the studies shows, however, that they used different methods of investigation; thus there is no need to look further for an explanation of the difference in the studies’ results.

The argument's reasoning is flawed because the argument fails to

(A) distinguish between a study produced for the purposes of the operation of government and a study produced as part of university research

(B) distinguish between a method of investigation and the purpose of an investigation

(C) recognize that only one of the studies has been properly conducted

(D) recognize that two different methods of investigation can yield identical results

(E) recognize that varying economic conditions result in the average workweek changing in length

PT32, S1, Q10

To accommodate the personal automobile, houses are built on widely scattered lots far from places of work and shopping malls are equipped with immense parking lots that leave little room for wooded areas. Hence, had people generally not used personal automobiles, the result would have to have been a geography of modern cities quite different from the one we have now.

The argument's reasoning is questionable because the argument

(A) infers from the idea that the current geography of modern cities resulted from a particular cause that it could only have resulted from that cause

(B) infers from the idea that the current geography of modern cities resulted from a particular cause that other facets of modern life resulted from that cause

(C) overlooks the fact that many technological innovations other than the personal automobile have had some effect on the way people live

(D) takes for granted that shopping malls do not need large parking lots even given the use of the personal automobile

(E) takes for granted that people ultimately want to live without personal automobiles

Introduction

Let's begin this chapter by evaluating a simple argument:

| Cats are friendlier than dogs. |  |

Cats make for the best pets. |

What's wrong with this argument? Perhaps you might think…

- No! Dogs are friendlier than cats.

- Cats and dogs are about as friendly as one another.

- There is no accurate way to measure the friendliness of animals.

- Friendliness is not the primary consideration for what makes a best pet.

- There are other characteristics aside from friendliness, such as loyalty, that help determine a best pet.

- Dogs make for the best pets.

- There are pets other than cats and dogs that ought to be considered.

- There is no way to crown a definitive “best pet.”

All of these criticisms of the argument could, in real life, be valid. However, only some of these are representative of the types of reasoning flaws that you are typically asked to identify on the LSAT. Take a look through the list again if you'd like and see if you can determine which ones represent reasoning flaws.

For Identify the Flaw questions, you are not being asked to evaluate the validity of the premises, nor are you being asked, in any direct way, to evaluate the validity of the conclusion in and of itself. Rather, your task is to identify flaws in the relationship between the premises and the conclusion.

If you analyze the eight typical reactions above, you should see that the first three seem to question the validity of the premise on its own. #6 and #8 seem to question the validity of the conclusion on its own. Only #4, #5, and #7 represent flaws that call the relationship between the premise and the conclusion into question. These are the types of flaws you are consistently asked to identify on the LSAT.

If the previous few chapters have helped you get stronger at recognizing issues between premises and conclusion, this chapter should add to and reinforce that understanding. The reasoning skills required for Identify the Flaw questions are almost identical to those required for Assumption questions. In fact, these two question types can be considered two sides of the same coin.

It's a Flaw to Assume

For both Assumption and Identify the Flaw questions, we are expected to evaluate the connection between the evidence presented and the conclusion reached. There will always be a gap in this connection, and any such gap can be considered either as an unstated assumption or a flaw.

Let's use the earlier example to illustrate:

| Cats are friendlier than dogs. |  |

Cats make for the best pets. |

The author is making several assumptions in using this premise to support this conclusion, and most likely some of these assumptions are pretty obvious to you. He's assuming that friendliness is what determines a best pet (perhaps loyalty, intelligence, obedience, or protectiveness are factors). He's also assuming that there aren't animals other than cats and dogs that warrant consideration. Consider how an assumption can be presented as a flaw with just a few changes in wording:

“The author assumes that friendliness is the primary characteristic that defines a best pet.”

Can be changed to…

“The author takes for granted that friendliness is the primary characteristic that defines a best pet.”

“The author assumes no other pets need to be considered for best pet.”

Can be changed to…

“The author fails to consider other pets for best pet.”

Therefore, the work you've put into mastering Assumption questions should serve you well for Identify the Flaw questions. Remember that, in a general sense, assumptions play two broad roles—they either help to match up the premises and the conclusion (How does friendliness relate to best pet?), or they address other considerations relevant to the conclusion (What other pets need to be considered?).

We can use our understanding of these roles to shape how we think of Identify the Flaw questions. The right answer to any Identify the Flaw question will address one or both of the following concerns:

- Is there a premise–conclusion mismatch?

- What other factors has the author failed to consider in reaching his or her conclusion?

Let's discuss both issues in depth.

1. Is There a Premise–Conclusion Mismatch?

In the last chapter, we discussed “term” and “concept” shifts. Note that there will always be term and concept shifts between the premises and the conclusion (otherwise we'd just have the same sentence written twice!). What we want to be on the lookout for are the term or concept shifts that are significant enough to make us doubt that the premise is sufficient to validate the conclusion.

Here are a few examples of term and concept shifts that would be significant enough to warrant our suspicion:

P: People who floss regularly tend to have fewer gum problems later in life.

C: If you'd like to have fewer gum problems later in life, we recommend that you floss daily.

Who knows if daily flossing is the type of regular flossing that is good for you? Maybe flossing every 12 hours, or alternatively every three days, is the key.

P: The majority of voters will be Democrats.

C: Therefore, the Democratic candidate will receive the most votes.

Who knows if the Democratic voters will vote for this Democratic candidate?

P: Some of the judges were surprised by the flavors in the cake.

C: It's likely that they will give it a low score.

Maybe they were pleasantly surprised?

P: There are a lot more boys in this year's class than there were in last year's.

C: The girls will constitute a smaller proportion of this year's class.

For now, we'll leave it up to you to figure out what's wrong here.

If you are having trouble seeing these mismatches, there will be many more examples to come. If you think you've got it, great. Chances are, if you see a mismatch like this, the right answer will address it in one way or another. Now, the next thing to consider is, “How do the test writers make it more of a challenge to identify this mismatch?”

Let's use an example from earlier to discuss:

PT36, S1, Q12

The consumer price index is a measure that detects monthly changes in the retail prices of goods and services. The payment of some government retirement benefits is based on the consumer price index so that those benefits reflect the change in the cost of living as the index changes. However, the consumer price index does not consider technological innovations that may drastically reduce the cost of producing some goods. Therefore, the value of government benefits is sometimes greater than is warranted by the true change in costs.

The reasoning in the argument is most vulnerable to the criticism that the argument

(A) fails to consider the possibility that there are years in which there is no change in the consumer price index

(B) fails to make explicit which goods and services are included in the consumer price index

(C) presumes, without providing warrant, that retirement benefits are not generally used to purchase unusual goods

(D) uncritically draws an inference from what has been true in the past to what will be true in the future

(E) makes an irrelevant shift from discussing retail prices to discussing production costs

We are asked to identify the criticism to which the argument is MOST vulnerable. Keep in mind that typically, even when an Identify the Flaw question is asked in relative terms—“most vulnerable” seems to indicate that we may compare multiple flaws—there will be just one answer choice that actually represents a flaw in the argument.

Let's model the reading process as it might play out in real time:

The consumer price index is a measure that detects monthly changes in the retail prices of goods and services.

This is background information. The argument is about the consumer price index.

The payment of some government retirement benefits is based on the consumer price index so that those benefits reflect the change in the cost of living as the index changes.

This is also background. This sentence links the consumer price index to government retirement benefits.

However, the consumer price index does not consider technological innovations that may drastically reduce the cost of producing some goods.

The “however” sets up a contrast—the consumer price index doesn't consider this other factor. It's unclear at this point why this contrast is important.

Therefore, the value of government benefits is sometimes greater than is warranted by the true change in costs.

This is definitely the author's main point.

In terms of the general structure of the argument, what we have is background-background-counter to that background-“therefore” a conclusion. The conclusion is a consequence of the previous sentence:

“However, the consumer price index does not consider technological innovations that may drastically reduce the cost of producing some goods.”

At this point, we have a sense of the argument core:

| Consumer price index doesn't consider tech innovations that may drastically reduce cost of producing some goods. |  |

Value of government benefits sometimes greater than is warranted by true change in costs. |

It is often true, particularly for challenging questions, that even though the reasoning issues are in the core, the key to understanding these issues lies outside the core. That is, it is in the other information (the background, or opposing points) that we come to understand the significance of issues in the core.

What is the relevance of this premise to the conclusion? Well, the benefits are based on the consumer price index. The author is saying there is a problem here—the consumer price index doesn't represent potential reductions in production costs.

Is this really a problem? In the background information, we learn that benefits are based on the index so that they reflect changes in the cost of living. This makes perfect sense. After all, the benefits are presumably meant to be used for living costs. Are the benefits flawed because the index doesn't reflect production costs?

No. It's not. And there's the gap. The author inserts production costs into an argument that doesn't seem to warrant discussion of that factor.

Ideally, for most Identify the Flaw questions, you want to go into the answer choices with this type of very clear sense of what the flaw or flaws are in an argument. Even so, as you evaluate the answers, you want to make sure to work from wrong to right. That is, even if you have a strong prediction about the right answer, you want to, in your first time through the answer choices, be on the lookout for reasons why four of the five answers are wrong. This is the most effective and efficient way to arrive at the right choice.

Let's rewrite the core here and evaluate the answer choices one at a time:

| Consumer price index doesn't consider tech innovations that may drastically reduce cost of producing some goods. |  |

Value of government benefits sometimes greater than is warranted by true change in costs. |

(A) fails to consider the possibility that there are years in which there is no change in the consumer price index

Whether the index varies or stays the same has no direct bearing on whether production costs should be reflected in retirement benefits. We can eliminate this quickly.

(B) fails to make explicit which goods and services are included in the consumer price index

This also has no direct bearing on the core. We don't need to know about every single item on the index in order to evaluate this particular argument involving the index. We can eliminate this quickly.

(C) presumes, without providing warrant, that retirement benefits are not generally used to purchase unusual goods

This answer choice connects to the core in an interesting albeit indirect way—we can imagine that the consumer price index might be based on items that are usually purchased. Still, this answer choice has no direct bearing on the conclusion. Whether benefits are used for usual or unusual goods has no direct impact on whether production costs should be reflected in retirement benefits.

(D) uncritically draws an inference from what has been true in the past to what will be true in the future

This argument does not use evidence from the past to claim that something will be true in the future. We can quickly eliminate this too.

We're down to just one:

(E) makes an irrelevant shift from discussing retail prices to discussing production costs

This is the answer we anticipated. The fact that the consumer price index doesn't reflect changes in production costs is irrelevant to the issue of how the consumer price index is used to set benefits.

Consider now how the writers made it more of a challenge for you to identify the mismatch in the core. One challenge was the volume of information—it was imperative that you prioritized correctly. The second was that, in order to fully understand the elements discussed in the core, we had to reference the background information.

Let's take a look at another example. See if you can spot the significant shift between the premises and the conclusion in the argument before you evaluate the answer choices.

PT16, S3, Q24

A birth is more likely to be difficult when the mother is over the age of 40 than when she is younger. Regardless of the mother's age, a person whose birth was difficult is more likely to be ambidextrous than is a person whose birth was not difficult. Since other causes of ambidexterity are not related to the mother's age, there must be more ambidextrous people who were born to women over 40 than there are ambidextrous people who were born to younger women.

The argument is most vulnerable to which one of the following criticisms?

(A) It assumes what it sets out to establish.

(B) It overlooks the possibility that fewer children are born to women over 40 than to women under 40.

(C) It fails to specify what percentage of people in the population as a whole are ambidextrous.

(D) It does not state how old a child must be before its handedness can be determined.

(E) It neglects to explain how difficulties during birth can result in a child's ambidexterity.

What's the author's conclusion?

…there must be more ambidextrous people who were born to women over 40 than there are ambidextrous people who were born to younger women.

How does he try to prove it? In this case, we can see that there are two premises that work together to support the conclusion:

A birth is more likely to be difficult when the mother is over the age of 40 than when she is younger.

and…

A person whose birth was difficult is more likely to be ambidextrous than is a person whose birth was not difficult.

Thus, we can think about the core as follows:

| Over-40 mother more likely to have difficult birth than when younger. + A person with difficult birth more likely to be ambidextrous. |

|

More ambidextrous people born to women over 40 than to younger women. |

Do you notice the mismatch? Think about it before reading on.

From these two premises, what can we conclude about people who are born to women over 40? Perhaps mothers over 40 are more likely to give birth to ambidextrous children, but that does not have to mean that they will be giving birth to a greater number of ambidextrous children. Notice that the conclusion is about the total number. Whether mothers over 40 give birth to a greater number of children would also depend on the proportion of children who are born to women over 40. If 50 percent of all children are born to women over 40, this argument makes a lot of sense. If 1% of all children are born to women over 40, well, the argument becomes significantly more dubious.

The point is not that you need to come up with hypothetical situations (though they can often be helpful in clarifying the specific mismatch). More important is that we recognize the mismatch between a likelihood and a total number, and that we recognize that the author has assumed a direct connection where there isn't one.

The correct answer, (B), reflects the consequences of this mismatch.

(B) It overlooks the possibility that fewer children are born to women over 40 than to women under 40.

None of the other answer choices address the gap between likelihood and amount.

Let's look back at an example we presented earlier:

P: There are a lot more boys in this year's class than there were in last year's.

C: The girls will constitute a smaller proportion of this year's class.

In this case, notice that the premise is about actual numbers, and the conclusion is about a proportion. As in the previous problem, this leads to a mismatch. We know nothing about the number of girls in this year's class—perhaps it has increased too, even more than the number of boys. In that case, the conclusion about the proportion could be incorrect.

The faulty link between proportion and amount is just one of the many issues that can be more easily spotted if you are consistently on the lookout for mismatches between the premise and the conclusion.

Now let's discuss the second of our primary concerns.

2. What Else Needs to Be Considered in Order to Evaluate the Conclusion?

Let's start this part of the discussion by evaluating another simple argument:

| Janice is strong. |  |

Janice is athletic. |

Hopefully, you are reading with a critical eye and can see immediately that this argument is flawed. You can say that the flaw has to do with a mismatch between premise and conclusion—strong and athletic are not the same thing—and that would be 100% correct.

Another way to think about this flaw is that being strong is just one part of being athletic. What we commonly consider as being athletic often also entails speed and coordination, along with other traits. Many LSAT arguments are flawed because the author considers only one or two of what ought to be many determining factors.

Let's look at another simple example:

| Janice is strong. |  |

She must work out daily. |

This is also a flawed argument because the author failed to consider alternatives, but in this case, it's a different type of consideration that has been forgotten: for what other reasons, and through what other means, could she be or get strong? Maybe she was born strong. Maybe she takes supplements to build muscle mass. We can't ignore these possibilities.

Take a look at one more argument. Identify the core, and try to figure out what else might be relevant to the conclusion.

PT19, S4, Q3

The number of calories in a gram of refined cane sugar is the same as in an equal amount of fructose, the natural sugar found in fruits and vegetables. Therefore, a piece of candy made with a given amount of refined cane sugar is no higher in calories than a piece of fruit that contains an equal amount of fructose.

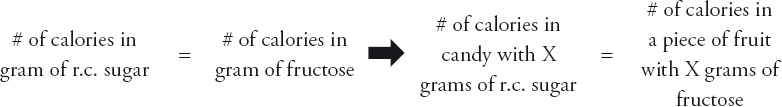

We can think of the argument core as follows:

What is the author failing to consider? Think about it for a second before reading on.

A piece of candy is going to have calories that come from ingredients other than sugar. A piece of fruit will have calories that come from elements other than fructose. That is, calories from sugar are just one part of the total calories for a piece of candy, and calories from fructose are just one part of the total calories for a piece of fruit. Maybe the other ingredients in the candy have a lot more calories than the non-fructose parts of the piece of fruit.

Let's take a look at the answer choices that came with this argument. Evaluate each one relative to the core before reading the comments.

(A) fails to consider the possibility that fruit might contain noncaloric nutrients that candy does not contain

Most of this answer sounds attractive, but since we're concerned with the number of calories, noncaloric nutrients are of no consequence.

(B) presupposes that all candy is made with similar amounts of sugar

We're comparing candy and fruit with equivalent amounts of sugar and fructose rather than, say, two pieces of candy made with unknown amounts of sugar, and therefore the author does not need to assume this to be true.

(C) confuses one kind of sugar with another

This is not the case. Notice it has little to do with our core.

(D) presupposes what it sets out to establish, that fruit does not differ from sugar-based candy in the number of calories each contains

What this answer means is that the argument is using the conclusion to justify the conclusion. This is not the case. Furthermore, the actual conclusion is not simply comparing the calories in fruit and candy, but in a piece of fruit and a piece of candy that have respectively equal amounts of fructose and sugar.

(E) overlooks the possibility that sugar might not be the only calorie-containing ingredient in candy or fruit

This is the answer we anticipated, and it is correct. The primary flaw in this argument was a failure to consider other relevant issues.

Now let's look back at an example from earlier in the chapter. Try solving it again if you'd like, and make sure to identify the flaw before moving on to the answer choices.

PT14, S2, Q22

Gallery owner: Because this painting appears in no catalog of van Gogh's work, we cannot guarantee that he painted it. But consider: the subject is one he painted often, and experts agree that in his later paintings van Gogh invariably used just such broad brushstrokes and distinctive combinations of colors as we find here. Internal evidence, therefore, makes it virtually certain that this is a previously uncataloged, late van Gogh, and as such, a bargain at its price.

The reasoning used by the gallery owner is flawed because it

(A) ignores the fact that there can be general agreement that something is the case without its being the case

(B) neglects to cite expert authority to substantiate the claim about the subject matter of the painting

(C) assumes without sufficient warrant that the only reason anyone would want to acquire a painting is to make a profit

(D) provides no evidence that the painting is more likely to be an uncataloged van Gogh than to be a painting by someone else who painted that particular subject in van Gogh's style

(E) attempts to establish a particular conclusion because doing so is in the reasoner's self interest rather than because of any genuine concern for the truth of the matter

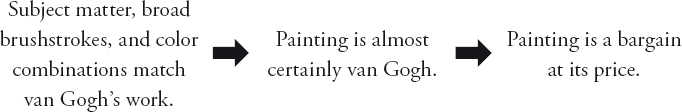

The gallery owner's ultimate point is that the painting is a bargain at its price (by the way, what price?). How does he get there? Through the use of an intermediate conclusion: evidence makes it almost certain that the work is indeed a van Gogh. What's the evidence? The subject matter, stroke style, and color combinations match those of his other works.

We can think of the argument core as follows:

In this argument, there are significant assumptions made at each point of connection.

In going from the intermediate conclusion to the conclusion, we are assuming that the painting being almost certainly a van Gogh is sufficient to conclude that the price of the painting, about which we have been given no information, is a bargain. We all know that van Gogh paintings are some of the most expensive in the world, but imagine if the price in question is $500 million. Is that still a bargain? We don't have enough information to say one way or the other.

There is an even more glaring jump from the original premise to the intermediate conclusion. We need to ask ourselves, are the three common characteristics mentioned (subject matter, brushstrokes, color combinations) enough to prove the painting to be a van Gogh? What else needs to be considered?

For one, surely, there are better, more specific ways to authenticate a van Gogh. It is the 21st century after all.

Furthermore, note that these are very broad and common characteristics—characteristics that paintings from other painters might share. Is it possible that another painter happened to paint similar subjects with broad strokes? Certainly. It's also easily plausible that it's a painting done deliberately in the style of van Gogh. He is an often studied and imitated artist.

The correct answer could have addressed any of these reasons to doubt the connections between the premises, the intermediate conclusion, and the final conclusion, and it happened to address a broad one: the evidence is simply not sufficient to prove that van Gogh painted the picture—someone else could have painted the picture in a style similar to his.

The correct answer is (D): provides no evidence that the painting is more likely to be an uncataloged van Gogh than to be a painting by someone else who painted that particular subject in van Gogh's style.

You might be asking at this point, “But wait…Doesn't answer (D) bring in outside information? How is it not out of scope?”

One of the best things you can do during the course of your studies is to develop solid instincts about which answers are “in scope” and which are “out of scope.” In this case, answer (D), the correct answer, brings up other artists, and perhaps this made the answer less attractive to you at first.

Many test-takers rely on matching up key words in the answer choices with those in the argument to determine what is “in scope.” While this might be helpful some of the time, it is not a reliable strategy. In fact, it will often be true that answers that can be considered out of scope will involve many key words that match those in the argument, and answers that will be in scope, like answer (D) here, will bring up elements that are not in the original argument.

The decision is not how the answer relates to the argument as a whole; for Assumption Family questions, the decision of in-scope and out-of-scope has to do with the relationship between the answer choice and the core. The answer is in-scope if you can see some relation between that answer and the core. It is out-of-scope if you can't. In this case, we can see that it is relevant to consider other painters when deciding whether or not van Gogh painted the picture.

Finding the core and evaluating the flaw or flaws in the core will set us up not only to find the right answer but also to quickly eliminate out-of-scope wrong answers. Very often, wrong answers are built using terms and ideas from other parts of the argument. If you don't know where to focus, these answer choices will seem much more attractive. If you are zeroed in on the core, you can more easily make quick eliminations.

Let's evaluate the incorrect answers. For Identify the Flaw questions, the majority of incorrect answers will have no direct connection to the core, or to the flaws that the argument is designed for us to anticipate. To illustrate the point, let's compare the answer choices to the core of the van Gogh argument:

(A) ignores the fact that there can be general agreement that something is the case without its being the case

There is no general agreement being used as a premise, nor is general agreement something that is required in order for the conclusion to be true.

(B) neglects to cite expert authority to substantiate the claim about the subject matter of the painting

We have no indication that expert authority is required for the argument to be sound, let alone specifically required for validating a match of subject matter. Don't be tempted into thinking that we've got to justify the premise!

(C) assumes without sufficient warrant that the only reason anyone would want to acquire a painting is to make a profit

Profit is not relevant to the core.

(E) attempts to establish a particular conclusion because doing so is in the reasoner's self interest rather than because of any genuine concern for the truth of the matter

If you are the suspicious type, this answer might be attractive to you (the owner just wants to turn a buck!). Because of this, answer (E) is probably the most attractive of the wrong choices. But we've been given no indication at all that the owner is unscrupulous, and it's not our task to figure out whom we should be suspicious of. Answer choice (E) may represent a tempting ulterior motive, but it does not represent a flaw in the reasoning used in the argument core.

Let's look at one more example for which it can be useful to think about “what else.” Take 1:20 to try this question on your own first. Make sure to read like a debater and try to identify at least one flaw before moving on to the answer choices.

PT33, S3, Q15

Scientists hoping to understand and eventually reverse damage to the fragile ozone layer in the Earth's upper atmosphere used a spacecraft to conduct crucial experiments. These experiments drew criticism from a group of environmentalists who observed that a single trip by the spacecraft did as much harm to the ozone layer as a year's pollution by the average factory, and that since the latter was unjustifiable so must be the former.

The reasoning in the environmentalists’ criticism is questionable because it

(A) treats as similar two cases that are different in a critical respect

(B) justifies a generalization on the basis of a single instance

(C) fails to distinguish the goal of reversing harmful effects from the goal of preventing those harmful effects

(D) attempts to compare two quantities that are not comparable in any way

(E) presupposes that experiments always do harm to their subjects

We can represent the core of the environmentalists’ argument as follows:

| Harm spacecraft does to ozone is equal to that a factory does in a year. + Harm from factory is unjustifiable. |

|

Harm spacecraft does to ozone unjustifiable. |

To evaluate this, let's read like a debater. Think up a reason that the harm done by the spacecraft is justifiable. Yes, the spacecraft trip damaged the ozone layer, but…perhaps the experiments led to important breakthroughs and to methods for repairing the ozone layer. Right! Just because something causes some harm doesn't mean it's harmful overall—there are plenty of medicines that we consider beneficial regardless of their nasty side-effects.

The point is this: in evaluating whether something is justifiable or not, we must consider the benefits as well as the harms. This is the flaw in the argument. The author hasn't considered the relative differences in the benefits that a spacecraft mission—to study the ozone—and a factory might have in determining whether the action is justified. The author has come to a conclusion based on an incomplete equation.

While we might expect the correct answer to say something like “ignores the potential environmental benefits of conducting the experiments,” the answer describes the flaw in a more abstract manner—another confirmation that we should work from wrong-to-right and not simply match words.

The correct answer is (A): treats as similar two cases that are different in a critical respect.

The author compares the harm from factories with harm caused by a spacecraft mission without considering the relative benefits, and one benefit specifically—the mission can give us information valuable in healing the ozone, whereas the harm a factory does can't benefit the ozone in any obvious way.

Let's take a quick look at the incorrect answers, and relate them to the core:

| Harm spacecraft does to ozone is equal to that a factory does in a year. + Harm from factory is unjustifiable. |

|

Harm spacecraft does to ozone unjustifiable. |

(B) justifies a generalization on the basis of a single instance

It's not clear what the generalization is, nor is it clear what the single instance is. This answer isn't relevant to this argument.

(C) fails to distinguish the goal of reversing harmful effects from the goal of preventing those harmful effects

This is a tempting answer, but it does not directly address the issue of whether the harm is justifiable or not. Distinguishing between reversing and preventing harmful effects may be helpful in comparing two approaches to fighting ozone harm, but such a distinction would not prove or disprove that the harm the spacecraft does is justifiable.

(D) attempts to compare two quantities that are not comparable in any way

It is true the argument compares the pollution caused by two elements (spacecraft and factories) that otherwise don't naturally match up together, but the argument does not compare two quantities that are not comparable. Furthermore, “in any way” is too extreme.

(E) presupposes that experiments always do harm to their subjects

Doing harm to subjects is not relevant to the core.

To review, we know that for all Identify the Flaw questions there is going to be something wrong with the reasoning in the core of the argument. Therefore, we want to read with as critical an eye as possible. Look at the flaw from two perspectives—in terms of a mismatch, and in terms of what else needs to be considered—to better understand the issues in an argument in a clear and specific way.

Keep in mind that even though flaws can often more easily be seen from one perspective or another, our two perspectives—what is the mismatch and what else needs to be considered—are not meant to be separate or opposite. In fact, there is great overlap between the two.

Consider two simple arguments we've discussed in depth:

| Cats are friendlier than dogs. |  |

Cats make for the best pets. |

| Janice is strong. |  |

Janice is athletic. |

Note that in both cases, there are flaws that can be considered from either perspective. It is correct to say that being a friendly pet and being the best pet are not the same thing. It is also correct to say that the author has failed to consider other pet types. The same dual perspective holds true for the second argument. It is correct to say that strong and athletic are not the same thing. It is also correct to say that being strong is only one part of being athletic, and that other issues need to be considered.

Your goal is not to categorize the flaw as fitting into one category or another. Your goal is to use both perspectives to understand the flaw as clearly as you can.

Causation Flaws

The most common reasoning flaws you'll see in Identify the Flaw questions are those that involve causation. Any claim of one element having a direct impact on another can be considered a claim of causation. Here are a few examples of causation claims:

“The success of the research project was due in part to the amount of money invested.”

“The dishwashing soap is what removed the stain.”

“Eating blueberries lowers one's chances of developing heart disease.”

In each of the above examples, the impact that one element or idea has on another is stated directly. Note that on the LSAT, issues of causation will appear in two main ways—they will either be stated explicitly in the conclusion, or they will be implicitly involved in the connection that is assumed between the premises to the conclusion.

Let's use two simple arguments to clarify the difference:

| Explicit: | Implicit: |

| “Ted didn't sleep well the night before the exam and performed poorly. Therefore, it's clear that his lack of sleep had a direct impact on his performance.” | “Ted didn't sleep well the night before the exam and performed poorly. He would have performed better if he could have gotten more sleep.” |

The arguments are very similar, and they both involve a claim about causation. Notice in the first example that the causation claim is stated explicitly: “His lack of sleep had a direct impact….”

In the second example, that claim is never explicitly stated. Rather, it is implied. The author is making an unstated assumption in using the evidence to validate the conclusion—he is assuming that lack of sleep must have had some impact on Ted's performance.

In either situation, you should be very suspicious of the causation reasoning. For Identify the Flaw questions, almost all claims of causation that appear either explicitly in the conclusion or implicitly in the assumptions made by the author can and should be considered faulty. In these cases, the evidence provided will not be sufficient to validate the claim of causation.

This is a very important point to remember because the writers of the exam will do their best to make these claims of causation seem sound. In fact, some of the most challenging questions involving causation are challenging because the argument seems so very reasonable. Therefore, go in knowing that you should be suspicious! Consider the following example:

Studies indicate that older antelope are, on average, more cautious than younger antelope. This proves that getting older causes antelope to become more cautious.

This argument seems pretty sound, right? Older antelope are more cautious, so it must be true that getting older is what causes these antelope to become more cautious, right?

When we are given a claim that “A,” in this case getting older, has some direct impact on “B,” in this case becoming more cautious, and the argument seems sound, we can walk through the following checklist:

1. Does the reverse make some sense too? Could B have a direct impact on A? Instead of age having some impact on the amount of caution, could it be that the amount of caution has some impact on getting older? Hmmm. Perhaps it seems unlikely, but see if you can imagine how this might be true and we'll come back to it later.

2. Could it be that something else impacts both A and B? It could be that certain antelope happen to have these two characteristics—older age and more cautiousness—but that these characteristics do not cause, or have any sort of impact, on one another. As an analogy, a certain car may have dents on the exterior, and stains on the interior, but these two characteristics could very well have nothing to do with one another.

3. Could it be that A and B have no impact on one another? It could be that certain antelope happen to have these two characteristics—older age and more cautiousness—but that these characteristics have nothing to do with causing, or having any sort of impact, on one another. As an analogy, state parks in Idaho always have both entrance fees and trees, but while trees and fees may rhyme, they have no causal relationship.

Now, let's go back to the first consideration, “Could B cause A?” Could cautiousness have some direct impact on getting older? It might seem unlikely at first, but consider a herd of antelope, and consider in particular the young in the group. Imagine that some of these young are cautious, and some of them are not. We've all seen nature shows—what might happen to some of these less cautious antelope? Chances are, they are more likely to run into unpleasant circumstances.

We are told that older antelope are, on average, more cautious. Could this be because, on average, more cautious antelope are more likely to survive to an older age? That is, instead of caution increasing with age, it's possible that caution is what allows the antelope to reach old age—it's possible that B causes A.

Keep in mind that our job is not to evaluate which mode of causation is more likely, although having instincts in this regard can certainly be beneficial. It is more important that we simply recognize that the argument is flawed in assuming one path of causation when multiple paths are possible.

If you had trouble seeing some of the alternative paths, that's perfectly understandable. Getting in the habit of asking the above three questions whenever you run into a claim of causation should help you develop better instincts about possible alternative modes of causation. Even when we can't imagine specific alternatives, we'll be in great shape to answer questions. We can feel confident that we can get the question correct as long as we can do two things:

- recognize the claim or assumption about causation that the author makes, and

- stay open-minded to answer choices that present information about possible alternative modes of causation.

Let's look at an example from earlier to illustrate:

PT39, S4, Q20

Some people believe that good health is due to luck. However, studies from many countries indicate a strong correlation between good health and high educational levels. Thus research supports the view that good health is largely the result of making informed lifestyle choices.

The reasoning in the argument is most vulnerable to criticism on the grounds that the argument

(A) presumes, without providing justification, that only highly educated people make informed lifestyle choices

(B) overlooks the possibility that people who make informed lifestyle choices may nonetheless suffer from inherited diseases

(C) presumes, without providing justification, that informed lifestyle choices are available to everyone

(D) overlooks the possibility that the same thing may causally contribute both to education and to good health

(E) does not acknowledge that some people who fail to make informed lifestyle choices are in good health

Note that the conclusion of the argument is an explicit claim of causation: “Thus research supports the view that good health is largely the result of making informed lifestyle choices.” That is, making informed lifestyle choices has a direct impact on good health.

The evidence in this argument states a correlation between good health and high educational levels. What this means is that there is some statistical evidence that connects the people who happen to have good health and the people who happen to have high educational levels. Statistically speaking, having one changes the percentage chance that you have the other.

However, correlation is never sufficient to prove causation. That is, just because we know that there is a correlation between good health and high educational levels doesn't mean we know that good health is a part of the reason for high educational levels, or vice-versa. Perhaps both are consequences of another characteristic, such as living in a particular location. Or perhaps there is no causal connection, direct or indirect, between the two.

Let's think about our three questions:

- Could it be the other way around? Does “B” impact “A”?

- Could something else impact both “A” and “B”?

- Could it be that “A” and “B” have no direct or indirect impact on one another?

We know that the correct answer will typically address one of these issues.

- Could having good health help one make informed lifestyle choices? Maybe, but it is not likely. Regardless, we want to stay open-minded to this possibility when we evaluate the answer choices.

- Could something else impact both good health and informed lifestyle choices? Absolutely. As stated before, where a person lives is just one example of something that could have an impact on the likelihood of both.

- Could having good health and making informed lifestyle choices have no impact (or, in this case, a small impact) on one another? Yes. We've got a pretty strong conclusion here (“is largely the result”), and not enough evidence to back it up.

The correct answer for this question is (D): overlooks the possibility that the same thing may causally contribute both to education and to good health. The right answer addresses the second of the above concerns. But it was wise to remain open to the idea that it could have been any of them.

Did you notice that this argument also contains a term shift? The argument shifts from “high educational levels” to “informed lifestyle choices.” The correct answer to this Flaw question could have pointed out this mismatch as well.

Let's quickly discuss the incorrect answers:

(A) presumes, without providing justification, that only highly educated people make informed lifestyle choices

This is a tempting answer because it addresses the mismatch between education levels and informed lifestyle decisions. However, the word “only” makes this answer choice too strong. The argument involves generalizations—in shifting terms, the author is assuming a relationship between education and informed lifestyle choices, but not an exclusive one as this answer choice states.

(B) overlooks the possibility that people who make informed lifestyle choices may nonetheless suffer from inherited diseases

It may be true that they suffer from inherited diseases, but we've been given no indication that the rate of inherited diseases is different for the groups—those who don't make informed lifestyle choices may also suffer from inherited diseases, and so it's unclear what impact this information has on the argument being made.

(C) presumes, without providing justification, that informed lifestyle choices are available to everyone

Whether the choices are available to everyone is not mentioned in the argument and has no direct bearing on it.

(E) does not acknowledge that some people who fail to make informed lifestyle choices are in good health

The author does not conclude that only people who make informed lifestyle choices are healthy. The conclusion is that such choices are the major factor in good health.

Let's take a look at another question that involves an explicit claim of causation. Try to anticipate potential answers, and see if one of the answer choices matches your prediction.

PT22, S2, Q10

The only motives that influence all human actions arise from self-interest. It is clear, therefore, that self-interest is the chief influence on human action.

The reasoning in the argument is fallacious because the argument

(A) denies that an observation that a trait is common to all the events in a pattern can contribute to a causal explanation of the pattern

(B) takes the occurrence of one particular influence on a pattern or class of events as showing that its influence outweighs any other influence on those events

(C) concludes that a characteristic of a pattern or class of events at one time is characteristic of similar patterns or classes of events at all times

(D) concludes that, because an influence is the paramount influence on a particular pattern or class of events, that influence is the only influence on that pattern or class of events

(E) undermines its own premise that a particular attribute is present in all instances of a certain pattern or class of events

In this argument, the author makes a very strong claim of causation—self-interest is the chief influence on human action. The evidence might seem very strong—self-interest is the only motive that influences all human actions!

But does that mean it's the chief influence?

Well, fortunately, we can use our familiarity with the exam to our advantage here. We know there's something wrong with the argument. So, what we're thinking is:

“Is it possible that self-interest is a part of every action, but not the chief influence?”

Absolutely. Perhaps, looking at the argument from this critical perspective, it might be easier to see how one characteristic or element may always be present in another, but not the chief influence. Imagine a dinner where the only thing that is common to all dishes is salt and pepper. Would we say that salt and pepper are the chief flavors in the meal? Not necessarily. Even though self-interest is always there, perhaps something else, such as a desire to have a positive impact on the lives of others, has a much stronger influence on our actions.

The flaw in the argument is that the author assumes that just because self-interest is a part of every action, it must be the chief influence in every action.

Answer choice (B), the correct answer, addresses this issue: takes the occurrence of one particular influence on a pattern or class of events as showing that its influence outweighs any other influence on those events.

The answer is worded in a challenging way, but it essentially gives us the information we expect. The argument is flawed in that it assumes that how often a characteristic appears translates to how strong an influence that characteristic is.

Let's break down the incorrect answer choices:

(A) denies that an observation that a trait is common to all the events in a pattern can contribute to a causal explanation of the pattern

This answer choice is very attractive because it can easily be misread, but notice that what it is saying is that the author denies that self-interest can have an influence—this answer choice is actually the opposite of what we are looking for.

(C) concludes that a characteristic of a pattern or class of events at one time is characteristic of similar patterns or classes of events at all times

This is not what is happening in the argument. The author is not concluding that a characteristic that appeared once appears always.

(D) concludes that, because an influence is the paramount influence on a particular pattern or class of events, that influence is the only influence on that pattern or class of events

This answer choice is about whether a chief influence is necessarily the only influence. We are interested in whether the sole common influence is necessarily the chief influence.

(E) undermines its own premise that a particular attribute is present in all instances of a certain pattern or class of events

The premise is not undermined, and so we can eliminate this choice.

Let's take a look at another problem. Here, no claim of causation is stated explicitly, but the argument does have a causation issue. See if you can spot it before looking at the answer choices:

PT14, S4, Q18

According to a government official involved in overseeing airplane safety during the last year, over 75 percent of the voice recorder tapes taken from small airplanes involved in relatively minor accidents record the whistling of the pilot during the fifteen minutes immediately preceding the accident. Even such minor accidents pose some safety risk. Therefore, if passengers hear the pilot start to whistle they should take safety precautions, whether instructed by the pilot to do so or not.

The argument is most vulnerable to criticism on the grounds that it

(A) accepts the reliability of the cited statistics on the authority of an unidentified government official

(B) ignores the fact that in nearly one quarter of these accidents following the recommendation would not have improved passengers’ safety

(C) does not indicate the criteria by which an accident is classified as “relatively minor”

(D) provides no information about the percentage of all small airplane flights during which the pilot whistles at some time during that flight

(E) fails to specify the percentage of all small airplane flights that involve relatively minor accidents

For the previous two questions, we looked at arguments that have an explicit claim of causation—more specifically, arguments with causation conclusions that we are meant to evaluate and ultimately find fault with.

However, sometimes the causation flaw is not explicit—it exists in a faulty, unstated assumption that the author has made. That's the case in this problem. Notice that the conclusion does not contain a claim of causation. However, the author is assuming a causal relationship in reaching his conclusion.

To illustrate, let's separate out the argument core:

| In over 75% of minor accidents, pilot of small plane recorded whistling |  |

If passenger hears whistling, should take safety precautions |

The conclusion, in this case, is a suggestion of what one should do. If a passenger hears whistling, he or she should take safety precautions.

Why? How did the author reach this conclusion? What was his reasoning? What did he assume, or, more specifically, how did he interpret the evidence?

In reaching the conclusion that the passenger should take safety precautions, the author is implying that the whistling is indicative of a greater likelihood of danger—in other words, that whistling has some impact on the chances of being in an accident.

Is this assumption about causation sound? Let's run it through our questions:

- Could it be reversed? Could the likelihood of being in an accident make one whistle more? Not likely.

- Could there be some other influence on both? Perhaps boredom makes one whistle, and makes one more likely to get in accidents, but that's a stretch.

- Could it be that there is no connection between the two? Absolutely! It can just be a coincidence, or there could be some alternative explanation. Imagine, for instance, that over 75% of pilots just happen to always whistle while they fly. If that's the case, the author couldn't make the case that hearing whistling increases the likelihood of being in an accident.

The correct answer choice, (D), addresses this issue: provides no information about the percentage of all small airplane flights during which the pilot whistles at some time during that flight.

Without this information, we can't prove that whistling represents an increased likelihood of getting in an accident.

Let's take a look at the incorrect answers:

(A) accepts the reliability of the cited statistics on the authority of an unidentified government official

Notice that this answer choice puts into question the validity of our premise. That's not our job here. This does not represent a reasoning flaw, and we are looking for reasoning flaws only.

(B) ignores the fact that in nearly one quarter of these accidents following the recommendation would not have improved passengers’ safety

The argument is not about what happens after passengers take the recommended safety precautions, but rather whether they should take those precautions when they hear whistling. Furthermore, is a recommendation unwarranted if it helps improve safety only 75% of the time?

(C) does not indicate the criteria by which an accident is classified as “relatively minor”

This answer choice is not directly relevant to the reasoning in the argument.

(E) fails to specify the percentage of all small airplane flights that involve relatively minor accidents

This is a tempting answer, but ultimately out of scope. This answer choice is about the percentage of small airplane flights that involve minor accidents. Whether this percentage is 0.1% or 90%, it does not impact the relationship between whistling and the likelihood of getting in an accident.

Let's finish by revisiting a very unusual example of a problem involving causation:

PT32, S1, Q10

To accommodate the personal automobile, houses are built on widely scattered lots far from places of work and shopping malls are equipped with immense parking lots that leave little room for wooded areas. Hence, had people generally not used personal automobiles, the result would have to have been a geography of modern cities quite different from the one we have now.

The argument's reasoning is questionable because the argument

(A) infers from the idea that the current geography of modern cities resulted from a particular cause that it could only have resulted from that cause

(B) infers from the idea that the current geography of modern cities resulted from a particular cause that other facets of modern life resulted from that cause

(C) overlooks the fact that many technological innovations other than the personal automobile have had some effect on the way people live

(D) takes for granted that shopping malls do not need large parking lots even given the use of the personal automobile

(E) takes for granted that people ultimately want to live without personal automobiles

In this argument, the causal relationship is not given to us as a conclusion, nor is it something simply assumed by the author. Notice that it is given to us explicitly as a premise. What is the cause? We need to accommodate personal automobiles. What is the effect? A variety of consequences to our living environment. Note that because this cause and effect relationship is given to us as a premise, it is not our job, in this case, to evaluate its validity. Rather, we're meant to evaluate its relationship to the conclusion. Let's take a look at the argument core:

| We've designed our geography to accommodate the automobile |  |

Without personal automobiles, our geography would be quite different. |

Note that the flaw here is not in assuming the validity of one cause, but rather in seeing that one cause as the only potential cause. The author states that without personal automobiles, the geography of modern cities would be quite different. We know that personal automobiles have led us to a certain type of geography, but are they the only cause that could have led to that geography? Do we know for sure that the geography of modern cities would be different without the personal automobile?

It's possible, but far from certain. We can imagine, perhaps, that we could have evolved to have personal motorcycles, or helicopters, and perhaps the geography would then have resulted in something similar. The flaw in this argument is that the author assumes one cause to be the only cause. Answer choice (A), the correct answer, addresses this issue:

(A) infers from the idea that the current geography of modern cities resulted from a particular cause that it could only have resulted from that cause

We could also look at this through the lens of more formal conditional logic. The premise tells us that cars  cities built the way they are, and (A) suggests that NO cars

cities built the way they are, and (A) suggests that NO cars  cities NOT built the way they are. It is logically invalid to simply negate both sides of a conditional statement.

cities NOT built the way they are. It is logically invalid to simply negate both sides of a conditional statement.

Let's take a look at the incorrect answer choices:

(B) infers from the idea that the current geography of modern cities resulted from a particular cause that other facets of modern life resulted from that cause

Other facets of modern life are out of scope.

(C) overlooks the fact that many technological innovations other than the personal automobile have had some effect on the way people live

This gives us other causes, but not causes for a certain geography. Rather, this answer proposes causes for “the way people live.” This would be a good answer if it were worded slightly differently: “overlooks the fact that many technological innovations other than the personal automobile [other causes!] have had some effect on geography.”

(D) takes for granted that shopping malls do not need large parking lots even given the use of the personal automobile

This answer might be attractive if it is misread, but note that it says that the argument takes for granted that shopping malls do not need large parking lots—this is the reverse of what the author discusses, and it is not something that is therefore taken for granted.

(E) takes for granted that people ultimately want to live without personal automobiles

What people want is irrelevant.

The Last Hurdle: Digging Out the Correct Answer

Okay. You've read through the argument, identified the core, and you have a good understanding of the gap or flaw. Are you done with the heavy lifting? For the most part, yes. But the test writers can throw a few more challenges your way. Let's take a look at two ways that the LSAT makes the right answer harder to identify.

To begin, go ahead and try the following two questions. Give yourself 2:40 to 3:00.

PT34, S2, Q3

Restaurant manager: In response to requests from our patrons for vegetarian main dishes, we recently introduced three: an eggplant and zucchini casserole with tomatoes, brown rice with mushrooms, and potatoes baked with cheese. The first two are frequently ordered, but no one orders the potato dish, although it costs less than the other two. Clearly, then, our patrons prefer not to eat potatoes.

Which one of the following is an error of reasoning in the restaurant manager's argument?

(A) concluding that two things that occur at the same time have a common cause

(B) drawing a conclusion that is inconsistent with one premise of the argument

(C) ignoring possible differences between what people say they want and what they actually choose

(D) attempting to prove a claim on the basis of evidence that a number of people hold that claim to be true

(E) treating one of several plausible explanations of a phenomenon as the only possible explanation

PT34, S2, Q9

A university study reported that between 1975 and 1983 the length of the average workweek in a certain country increased significantly. A governmental study, on the other hand, shows a significant decline in the length of the average workweek for the same period. Examination of the studies shows, however, that they used different methods of investigation; thus there is no need to look further for an explanation of the difference in the studies’ results.

The argument's reasoning is flawed because the argument fails to

(A) distinguish between a study produced for the purposes of the operation of government and a study produced as part of university research

(B) distinguish between a method of investigation and the purpose of an investigation

(C) recognize that only one of the studies has been properly conducted

(D) recognize that two different methods of investigation can yield identical results

(E) recognize that varying economic conditions result in the average workweek changing in length

Challenge #1: Abstract Language

A common way that test writers will try to challenge you is to write the answer choices using generalized, or abstract, language. Most of these answer choices will refer to the underlying reasoning or logic in the argument, and it makes perfect sense that these questions would work this way. After all, you are being tested on your ability to evaluate the underlying reasoning or logic—whether the argument is specifically about potatoes or workweeks is secondary to the test writer.

The great news is that reading for the core, and for structural flaws, in the manner that we've recommended up to this point, is the ideal way to prepare to evaluate an abstract or generalized answer choice.

The bad news is that for many of these questions, it is almost impossible to identify the correct answer if you haven't anticipated it. Most of the answer choices will sound very attractive, and most of the incorrect answers will be answers that could be correct for other arguments. This makes it even more important that you are strong at finding the core, and recognizing common flaws.

Let's look back at one of our two examples to review this issue more in depth:

PT34, S2, Q3

Restaurant manager: In response to requests from our patrons for vegetarian main dishes, we recently introduced three: an eggplant and zucchini casserole with tomatoes, brown rice with mushrooms, and potatoes baked with cheese. The first two are frequently ordered, but no one orders the potato dish, although it costs less than the other two. Clearly, then, our patrons prefer not to eat potatoes.

Which one of the following is an error of reasoning in the restaurant manager's argument?

(A) concluding that two things that occur at the same time have a common cause

(B) drawing a conclusion that is inconsistent with one premise of the argument

(C) ignoring possible differences between what people say they want and what they actually choose

(D) attempting to prove a claim on the basis of evidence that a number of people hold that claim to be true

(E) treating one of several plausible explanations of a phenomenon as the only possible explanation

We can think of the argument core as follows:

| No one orders the potato dish |  |

Our patrons prefer not to eat potatoes |

Did you see a flaw when you read the argument initially? The author concludes that the patrons must not prefer potatoes, and the evidence he presents is that no one orders the potato dish. Could there be another reason no one orders the potato dish? Could it be the way that it's prepared? Perhaps the chef thinks capers go well with potatoes, but patrons don't. Perhaps patrons don't like the cheese that is being used. Perhaps people prefer to eat potatoes at home, or only as an accompaniment with meat.

As we've discussed before, it is not necessary for you to take the time to come up with these alternatives. What is important is that you recognize the fault in the reasoning: in using this evidence to validate the conclusion, the author has failed to consider other reasons why patrons don't order the potato dish—the author is thinking of one explanation as the only possible explanation. Answer choice (E), the correct answer, says just that: treating one of several plausible explanations of a phenomenon as the only possible explanation.

Let's discuss the incorrect answers:

(A) concluding that two things that occur at the same time have a common cause

This is a fault that is common to many arguments that appear in Identify the Flaw questions, but this is not a fault of this particular argument. We are not considering two things that happen at the same time. When facing abstract flaw answers, stand your ground. Check that the answer corresponds with the argument. Did the argument really claim that? Did it conclude that? Often these abstract answers refer to claims and conclusions that are simply not in the argument.

(B) drawing a conclusion that is inconsistent with one premise of the argument

This is not representative of a common fault that appears in flaw arguments, and it's not representative of a flaw in this particular argument. Stand your ground! There is no inconsistency between the premise and the conclusion.

(C) ignoring possible differences between what people say they want and what they actually choose

This answer choice addresses a more specific flaw. However, it's not a flaw in this argument—there is no confusion of what people say they want and what they choose. The argument is about what people actually want and what they choose.

(D) attempting to prove a claim on the basis of evidence that a number of people hold that claim to be true

We are not told that a number of people believe that the patrons don't like potatoes.

Remember, the key to recognizing correct answers written in an abstract or generalized way is to read for the core and anticipate the reasoning flaw. When stuck between a couple of answer choices, do not simply compare them against one another—this will lead you nowhere! Instead, compare each one to the argument core. Figure out which one best applies to the situation in the argument, and to your understanding of the core.

Here are some more examples of the types of abstract language answers you may face on the exam:

| Abstract Answer | In Our Words… | Example |

| It assumes without warrant that a condition under which a phenomenon is said to occur is the only condition under which that phenomenon occurs. | The argument assumes that one way is the only way. | When businesses on Main Street fail there is commercial space available in the downtown district. Since there is commercial space available in the downtown district, it must be true that businesses on Main Street failed. (Maybe there's another reason space is available.) |

| Presumes that a condition necessary for an outcome is sufficient for that outcome. | The argument assumes that because something is required for an outcome to be true, it guarantees that the outcome will be true. | All NFL linemen weigh over two hundred pounds. Since Ted weighs over two hundred pounds, he must be an NFL lineman. (Not everyone who is over two hundred pounds is an NFL lineman!) |

| Takes for granted that if one phenomenon co-occurs with another, then the two phenomena must be causally related. | The argument assumes from a correlation that there must be a cause and effect relationship. | Those who have a computer at home have higher incomes on average than those who do not have a computer at home. Thus, having a computer at home leads to a higher income. (Having a computer and a higher income can both be due to other factors, or they can have no causal connection.) |

| It sets up a dichotomy between alternatives that are not known to be exclusive. | The argument assumes a limited number of possibilities when there could be more. | Since those who love our show already watch it and those who hate our show can't be convinced to watch it, advertising will have no impact on our viewership totals. (What about those who don't have a strong opinion about the show, or have never heard of it?) |

| Takes for granted that a claim is false based on evidence about the source of the claim rather than any evidence about the claim itself. | The argument makes assumptions about a claim based on the trustworthiness of the source. | Company X claims that its chemical products are completely safe for use at home. This is absurd, since Company X is only concerned with profits and cannot be trusted. (Even if the company is only concerned with profits, the chemical product can still be completely safe.) |

| Infers from a claim about a single instance of a class that the class must itself possess that characteristic. | The argument assumes that what is true of the parts is true of the whole. | The top scorer in the league is on the Cosmos. Therefore, the Cosmos must have scored more goals than any other team in the league. (One star player does not make a team. What about the other players?) |

| Too hastily draws a conclusion about what is a matter of fact from evidence that suggests a mere suspicion. | The argument assumes that an opinion is enough to prove the point being made. | John believes that he'll get a “B” in biology this semester, so when his grades are released late next week, his biology grade will in fact report a “B.” (Oh, if only life were that easy! How do we know that John's belief is correct?) |

| Confuses a relative comparison about one aspect of two different phenomena for an absolute claim about the two phenomena. | The argument assumes that a comparison allows us to infer something absolute. | Training a lion is safe, as anyone can see by simple comparison: those who train sharks are twice as likely to get injured as those who train lions. (Just because something is safer than training sharks does not mean it is actually safe!) |

Challenge #2: From Another Point of View

Sometimes you will do everything correctly and come to understand the flaw or flaws perfectly, and you get to the answer choices and still…none of the answers fit what you are looking for! What could be wrong?

Perhaps that didn't happen to you with this next problem, but in any case, let's use it to illustrate the issue:

PT34, S2, Q9

A university study reported that between 1975 and 1983 the length of the average workweek in a certain country increased significantly. A governmental study, on the other hand, shows a significant decline in the length of the average workweek for the same period. Examination of the studies shows, however, that they used different methods of investigation; thus there is no need to look further for an explanation of the difference in the studies’ results.

The argument's reasoning is flawed because the argument fails to

(A) distinguish between a study produced for the purposes of the operation of government and a study produced as part of university research

(B) distinguish between a method of investigation and the purpose of an investigation

(C) recognize that only one of the studies has been properly conducted

(D) recognize that two different methods of investigation can yield identical results

(E) recognize that varying economic conditions result in the average workweek changing in length

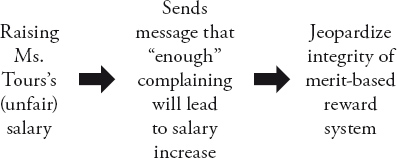

Here is a simplified version of the core:

| the two studies used different methods of investigation |  |

no need to look further for an explanation of the difference in the studies’ results |

Do you spot a flaw in the reasoning here? It's actually very similar to that in the previous argument—the author assumes one reason when others could be plausible. In this case, he assumes that because two studies used different methods of investigation, this was the reason for the difference in the studies’ results. Couldn't it be that, though the methods of investigation were different, something else could have caused the difference in the results?

We go in anticipating an answer that addresses this issue. One way it could be worded is that “the author fails to recognize that there could be other reasons for differences in the studies’ results.”

Unfortunately, we don't have that in the answer choices! Let's review what we've got:

The argument's reasoning is flawed because the argument fails to

(A) distinguish between a study produced for the purposes of the operation of government and a study produced as part of university research

We're not told that the governmental study was done for the purposes of the operation of the government, and the author does recognize differences between the two studies discussed.

(B) distinguish between a method of investigation and the purpose of an investigation