Not all ambiguity comes from the same place, so once you recognize ambiguity in requirements, you'll still need to locate the source. To help you develop some ways of classifying the sources of ambiguity, let's pause to "participate" in one of our experiments in ambiguity. To get the most of this experiment, imagine that you are actually participating in the scene described.

You've just driven twenty-three miles through heavy traffic to attend a professional seminar entitled "Convergent Design Processes, or Getting the Ambiguity Out," given by a Professor Donald C. Gause. You expect to spend a pleasant day sharing design war stories with the other participants, but otherwise you have little idea of what to expect. You don't have high regard for the practical sense of professors, but with luck, the presenter might not be too dull. Maybe you'll even catch a few new ideas. After all, the seminar description promised help in identifying and defining the real design problem to be solved.

Your design consciousness is in high gear. You notice it is 8:55 a.m. on your Ralph Lauren watch (designed to maximize snob appeal), and you have just settled comfortably into your stackable plastic chair (designed to maximize storage efficiency for the hotel). You warm your hands on a styrofoam coffee cup (designed to minimize cost per serving to the caterer) filled to the rim with something resembling coffee (designed to pacify late-rising coffee addicts). You're about to glance at your watch again when a distinguished-looking woman in a navy blue polyester suit and red bow tie strides to the lectern and makes a few remarks about restrooms, fire exits, refreshment breaks, and lunch. She then glowingly introduces Professor Gause, but you decide you'll wait to see for yourself.

The first thing you notice about Professor Gause is that he is not dressed in the same fashion as his introducer, nor does he exude the same aura of organized efficiency. If anything, his aura is rather rumpled. He's wearing a wrinkled Harris tweed jacket, hiking shoes, and pants that look like he wore them in last night's tennis match and then slept in them. Nevertheless, he seems quite at ease and in control of the situation, with one exception.

He is scrutinizing the slide projector control as if it were a Venusian Death Ray Projector. Without looking up from his alien analysis, he announces, "It sure is nice to be here today." He then flicks up the first slide on a large screen directly behind the lectern.

You notice the slide is ever so slightly out of focus, enough to be irritating, but not enough to provoke anyone into saying anything. Without looking at the slide, Gause says off-handedly, "I like to use this as my focus slide."

Figure 3-1. The focus slide.

You bend down to tie your shoe and when you look up, you notice Gause has moved on to the next slide. In excited tones, he begins, "This is a seminar about convergent design, which I define as 'a design process that consciously and visibly recognizes, defines, and removes ambiguity as effectively as possible.'"

At this point, Gause turns around and notices that the slide is out of focus. He has evidently mastered the slide control because he adroitly brings the slide into sharp focus. Whew! What a relief not to be eyeballing fuzzy slides all day! Even worse would be listening to a design lecturer who apparently didn't care about his own designs.

Figure 3-2. The Convergent Design Processes slide.

You now settle back, confident that everything is under control, as Gause uses a transportation device example to illustrate how to create an ambiguity metric. Then he has you break into groups to work on the example—a delightful respite from the lecturing you expected to go on all day. You're fascinated to notice in your group the first estimates of market cost for a transportation solution range from $1 to $1 million. Then each group works through ten questions supplied by Gause, and the estimate range becomes $49.95 to $1 million.

You're having a pleasant time, and the lecturer's scheme for recognizing ambiguity seems reasonable enough. Then, things seem to bog down when he starts lecturing about some misty theory of design. You hear, "It's time for a required break, and we always meet requirements. After all, quality is meeting requirements, right?"

During the break, you share some tidbits with the other attendees and learn everyone calls the speaker "Don." After you've milled around for about fifteen minutes, Don announces, "Your break is now one hundred percent complete. Are you on schedule?" Everyone agrees, whereupon Don proclaims, "It's time to blast off in new directions."

When everyone is seated, Don asks the class to answer the question posed on the next slide. "You are to work independently," he says, "privately writing your best estimate so as to make a firm commitment, and capturing your first impressions so you won't forget them when you hear other opinions." A slide appears:

How many points were in the star that was used as a focus slide for this representation?

You're feeling suspicious and more than a little tricked, but you decide to comply when Don flips to a blank slide and says, "This question has everything in the world to do with design. For example, you might think of this as simulating a critical design decision that depends on a correct answer to the question. You might encounter this situation when an important event occurred but you did not realize it was important at the time it happened. Everyone then has to recreate as much of the important information as possible. After you write down your answer," he promises, "I'll give you some specific examples. Now, please write down your answer to the question posed on the screen."

After you write down your answer, Don gives the promised example. "Remember Legionnaires' Disease in which many of the attendees of the American Legion convention at Philadelphia's Bellevue Stratford Hotel became ill some time after returning home? People died before a pattern was recognized and identified. Although an important medical event had occurred, nobody realized anything important was going on until some time later—just as you may not have recognized the focus slide was important. When the importance finally was recognized, the best they could do was reconstruct as much information as possible for seeking the cause and designing the treatment and future prevention.

"There are many other examples," Don continues, "such as collapsing structures, penetration of security schemes, and accidents of all kinds, when the designers cannot duplicate the events they are trying to understand and to prevent with new designs. In fact, people were not even willing to go back to the Bellevue Stratford under any circumstances, and eventually the fine old landmark was torn down. That's why I've asked you to do the best you can, short of actually flipping back to the star slide."

1. What do you think the answer is to the question posed on the screen?

2. With 100 people attending the seminar, how many different answers did the participants write down as their first-impression answer to the question?

3. What factors do you think are responsible for the differences among answers?

4. Write down, verbatim to the best of your recall ability, the question that you think you answered in question 1.

5. Write down the variants to the question you think the seminar participants wrote when they were asked to recall the question they thought they were answering.

Answer all the questions to the best of your ability before continuing.

As you have probably guessed, this seminar actually took place. We provided this re-enactment to let you experience a few sources of ambiguity firsthand.

What do you think the answer is to the question posed on the screen? Only you know the answer to this, but keep it in mind as we discuss the actual seminar results.

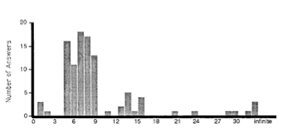

With 100 people attending the seminar, how

many different answers did the participants write down as their

first-impression answer to the question? The 100 participants

provided 18 different answers, as illustrated in Figure

3-3.

Figure 3-3. histogram of answers to the "how many points" question.

What factors do you think are responsible for the differences among answers? You can understand why other people's answers were the same as or similar to your original estimate, but you may be surprised by some of the answers in Figure 3-3. One way of understanding what went on in people's minds is to clump the results into clusters based on gaps in the histogram (see Figure 3-4). In our experience, there are four possible sources for these differences: observational, recall, and interpretation errors, plus problem statement ambiguity.

Figure 3-4. Histogram of clumped answers to the question.

No two human beings can be expected to see things identically (observational error) or to retain what they did see identically (recall error). If you're not too egotistical, you can probably understand the error may be yours as well as those who differ from you but share your cluster. Remember, the slide was deliberately shown in a haphazard manner, lasting for less than a minute at a time when people weren't paying much attention. Remember also, a lot of seemingly unrelated activity, including a fifteen-minute break, occupied the two hours between participants' seeing the slide and being asked the question. No one had any reason to believe the slide would ever be considered again.

All this explains the spread within your own cluster, but how can we explain the extreme answers? If you were in the majority cluster, you thought the answer was somewhere between five and nine points. You can easily recognize a five-pointed star, but the star on the screen seemed more awkward and asymmetrical than that. Thus you reasoned it must have at least five points, and perhaps a few more. How could any intelligent, well-adjusted, well-meaning person earnestly believe that the star had only one or two points, or for that matter, 29, 30, or 32? Surely Don must have planted a few shills among the participants.

Could the reason be that the question, as asked, is subject to different interpretations? The three people who claimed the star had an infinite number of points must have thought the star was composed of a series of continuous line segments. As high-school geometry teaches us, any continuous line segment contains an infinite number of points, so under that interpretation, these three answers were certainly correct and understandable.

Each cluster can similarly be explained by some other interpretation of the question . This then is a third major source of ambiguity, in addition to errors of observation and recall. Had there been only a single cluster containing all hundred responses, the interpretation ambiguity might have gone unnoticed. We notice differences in interpretation because of the different clusters, and each cluster may represent a different interpretation of the question.

Similarly, had the original image been clearly in focus and the subject of much attention at the time it was displayed, almost all of the variation would have been the result of differences in interpretation and recall, not observation. And, had the question been asked while the slide was still visible, recall errors would have been virtually eliminated, leaving only interpretation differences. The histogram would have shown no variation within clusters.

In other words, interpretation error tends to produce separate clusters, while observational and recall errors tend to manifest themselves as variations within each cluster. We can use this difference with the results of any ambiguity poll to help isolate the sources, rather than just the quantity of ambiguity.

Of course, this way of interpreting clusters is not a hard-and-fast rule. Because the clustering itself is a visual, intuitive process, we may err in the way we define cluster boundaries. One participant in our sample said there were eleven points, and we decided to place that answer in a separate category because there were no answers of ten or twelve. But perhaps this person used the same interpretation as the 5-9 group, or the 13-16 group, but had poor recall or observation.

On the other hand, there could be two interpretations masked within the same cluster just because both happened to lead to the same estimate. Such different interpretations would go unrecognized by the clustering heuristic, though they may surprise us by resolving into separate clusters in a later poll.

The clustering approach must therefore be viewed as a useful indicator of ambiguity, rather than a scientifically guaranteed and validated means of defining its presence and isolating its source.

In the seminar, we had the luxury of being able to ask the participants what they were thinking at the time they answered each question. In real development work, of course, this kind of questioning is not a luxury, but a necessity. The most important reason to tabulate the responses and visualize their spread in a histogram is not the histogram itself, but the discussion that follows. For example, after considerable discussion of possible interpretations of both histograms, we took another poll. This new poll revealed the results shown in Figure 3-5.

Figure 3-5. Clumped results of the second poll compared with the first.

The first poll, insofar as people followed directions, was independent, though we must always be a bit wary of the idea of complete independence. Some people might have discussed the star slide during the break, and some might have actually peeked at their neighbors' answers. Given the structure of the exercise, such dependence effects are probably small.

Not so, of course, once the histograms had been posted and the various interpretations discussed. The histogram in Figure 3-5 shows a number of changes, the clearest being a shift away from the majority viewpoint (5-9) toward more extreme views (0-2 or infinite). In discussing the shifts, the participants confirmed they had changed their answers because they had seen the problem in a different light. The change was due to new problem interpretations, not to altered recall or improved observation. Did you, in fact, consider changing your interpretation when you read this discussion?

Write down, verbatim to the best of your recall ability, the question you think you answered in question 1.

Again, only you know what you wrote down. Put this in front of you now as we discuss this and the fifth question.

Write, down the variants to the question you think the seminar participants wrote when they were asked to recall the question they thought they were answering.

Recall the exact question had been removed from the screen when the participants were asked, "This time, once and for all, please write down the answer to the question that was posed on the screen." Not having the question visible introduces yet another source of ambiguity: problem statement ambiguity.

Without the question to refer to, we can easily imagine not all participants were working on the same problem. Yet, until they were challenged by questions four and especially five, the participants failed to recognize the possibility of problem statement ambiguity. They were each quite content to launch into their own solution and, in some cases, to defend their solution to their fellow participants—totally unaware they might be working on different problems.

At this point in the seminar, we collected the answers to question four. Here are the more common responses:

1. How many points did the star have?

2. How many points were there in the first slide?

3. How many points did the star have in the first slide?

4. How many points were on the star that was used as a focus slide?

5. How many points were on the star in the first slide of this presentation?

6. How many points were in the focus star at the beginning of this presentation?

7. How many points were on the star that was used for focusing?

8. How many points did the star used for focusing at the beginning of the presentation have?

9. How many points (external) are on the star I used to focus?

10. How many points were there on each star on the slide used for focusing?

11. How many points did the star have that was used as a focus slide?

12. How many points were on the star that was used to focus at the start of the class?

13. What was the number of points on the star slide that was used to focus on?

14. How many points were in the focus slide star?

15. How many points in the picture of the star, used as a slide?

16. How many points were there in the star on the slide?

17. How many points were shown on the test star?

18. How many points are on the star which was used as a focus slide?

19. How many points were on the star slide used to focus at the beginning of the slide presentation?

20. How many points did the star shown at the start of the presentation have?

21. Determine how many points were present in the star shown earlier in the slide presentation?

22. How many points were there in the original foil which was used to focus the foils?

24. How many points were on the star that was shown at the beginning of the lecture?

25. How many points were on the focus slide?

26. How many points were on the star shown as the first slide?

You may be tempted to conclude these questions are all more or less equivalent restatements of the same basic question. Certainly, in a seminar exercise, we can regard the whole question as trivial, but if we consider the exercise as a simulation—a model of the real world-then we cannot treat the exact wording so casually. In real situations, like the Legionnaires' Disease example, the questions are vastly more complex, and the situation far more serious. The exercise severely underestimates both the amount and importance of possible problem ambiguity in the real world.

Our problem statements must be precise, yet each variant statement of this relatively trivial problem does produce a different way of looking at the problem, which in turn produces a different solution. In real situations, differences as subtle as these spell the difference between a successful project and disaster.

1. When working with requirements, use the recall heuristic directly. Simply take away the written requirements document and ask each participant to write down, from memory, what it said. Places where recall differs indicate ambiguous error-prone parts of the document. This is an important step because very few people will actually refer to the requirements document as they work, preferring to work with their memory of what the document says. Therefore, a document easy to remember correctly is much less likely to lead to design mistakes.

2. Use the star exercise as a demonstration early in the requirements process to get people thinking in terms of ambiguity and their role in it.

The most important reason to tabulate the responses and visualize their spread in a histogram is not the histogram itself, but the discussion that identifies the sources of ambiguity present. Interpretation ambiguity tends to produce separate clusters, while observational and recall ambiguities tend to manifest themselves as variations within each cluster.

Attempting to recall the requirement or problem statement verbatim will reveal ambiguity, which must be removed before a successful requirement can be developed.

Use the clustering heuristic with the results of any ambiguity poll to help isolate the sources, rather than just the quantity of ambiguity.

1. Question participants about the interpretation of some part of the requirements document, and clump the results into clusters.

2. Analyze the clusters by asking people within each what they were thinking.

3. Isolate observational error, when people saw things differently, and recall error, when people did not retain what they saw. These may produce spread within a cluster.

4. To account for spreads between clusters, ask participants to recall, without re-reading, the question they believe they were asked. This heuristic tends to spot interpretation ambiguity.

5. After people discuss their observations, changes will be due to new problem interpretations, not to altered recall or improved observation.

Anyone who needs to understand the requirement, or any representative of a group of people who need to understand it, can usefully participate in this exercise to identify sources of ambiguity.