"Don't stand chattering to yourself like that," Humpty Dumpty said, looking at her for the first time, "but tell me your name and your business." "My name is Alice, but—"

"It's a stupid name enough!" Humpty Dumpty interrupted impatiently. "What does it mean?"

"Must a name mean something?" Alice asked doubtfully.

"Of course it must," Humpty Dumpty said with a short laugh: "my name means the shape I am—and a good handsome shape it is, too. With a name like yours, you might be any shape, almost."

—Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

Although you may believe, like Alice, that names are arbitrary, Humpty Dumpty had the right idea. The right name increases possibilities, while the wrong name stifles them. Don't you react to the Humpty Dumpty Project differently than you do to the Production Optimization Project?

The name is people's introduction to a project, and is another source of ambiguity. This chapter will present a heuristic for selecting an unambiguous name.

No matter how a project starts, it almost immediately develops a working title. A good working title unambiguously identifies the project without implying a solution. This name is crucial, for it is the way people are introduced to a project before there is a chance to inform them about the project's true business. Indeed, hearing the name may be the first time people become aware there is a project.

Often, a project develops more than one name, as in our example of the "Do Not Disturb Project" in Chapter 10. We once worked with the XYZ Company, which was building a software system for the ABC Bank. At XYZ, the project was known as "the Bank's System." At the bank, however, the project was called "the XYZ System." In this case, the lack of a unique, official name was symptomatic of both parties wanting to disown the project. We forced them to face the ambiguous ownership by running a naming competition among the bank's employees—who were, after all, some of the customers.

Even projects with official names tend to acquire nicknames, like "the Black Hole," or "Don's Project." Through its nicknames, you may learn much about how a project is progressing, but nicknames often introduce an element of ambiguity. If enough people talk about "Marketing's Project," instead of using the official name, the impact the project might have on other parts of the organization will soon be overlooked.

All project names—from working titles to official names—are dangerous sources of ambiguity, so choose them carefully. Choosing a name for the project can turn out to be a cogent way to explore what the project is required to do.

The name of a project can profoundly influence its results as well as the behavior of the participants. Recall in Chapter 10 how the Do Not Disturb Project and other names affected Jack and the others when they tried to generate ideas in their brainblizzard? Each participant's offering directly related to what they each believed was the project's name and, therefore, its purpose. To illustrate this point, we'll describe a demonstration we've used successfully in our seminars.

We divide the audience of professional designers into two groups of about fifty people each. The groups are then asked to organize themselves into teams of four to six people, and told that they will be given a design exercise and half an hour to create a conceptual solution. They are also told they'll be given an opportunity to present their results to the entire audience. If they do, however, they will be judged by everybody on two factors:

1. Did they actually produce a solution to the problem?

2. Is the solution highly innovative?

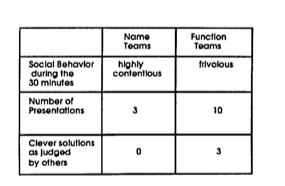

About twenty teams (ten in each of the two groups) set to work. What they don't know is the groups have been given slightly different problem statements. One group (let's call it the "Name Group"), gets the first description in Figure 12-1, while the second group (the "Function Group") gets the second description.

Figure 12-1. Two slightly different problem statements.

Notice that the only difference between the two descriptions is in the way requirement 3 is expressed, by name or by function. When the teams are all finished, they are invited to report if they wish.

Figure 12-2. Results of the furniture requirements demonstration.

The furniture requirements exercise shows vividly how the way things are named can affect both what is produced and how people behave while producing it. In the demonstration, the two groups worked on different sides of the room, so they could watch each other from a distance without hearing any details. Not only were their behaviors different, but they themselves—while they were working—noticed there was a striking difference between the two sides. In real life, however, we all may be equally influenced by names but have no control group with which to compare ourselves, so we may be totally oblivious to the way we've been influenced by the name.

The project name might be the first name encountered in doing requirements work, but it's by no means the last. We name requirements documents, parts of a product, characteristics of a product, pieces of work, people who take different roles in the project, groups of users, product features, and anything else we can lay our tongues on.

Now, check your predictions against the results in Figure 12-2, taken from a typical seminar.

Although a name may have been chosen carelessly and arbitrarily, it comes to be used as if it possessed a great deal more precision. Therefore, to create an unambiguous name, we offer the following heuristic. This same tool can also be used to change names, but changing is much harder than getting them right in the first place. Names have a way of sticking.

This heuristic involves a three-step process:

1. First propose a name.

2. Next offer three reasons why the name is not adequate.

3. Then propose another name to eliminate these problems.

The steps can be repeated until a useful name is developed. We used this process on the Elevator Information Device Project, and it was simple and natural.

Having understood more about the influence of names on possibilities, we can delve a bit deeper into why the heuristic works. Suppose we wanted to name the seminar's furniture design exercise. The first possibility springing to mind is the "Living Room Suite Project." Here is a list of arguments against this name:

1. We may want to use this furniture in other rooms.

2. "Suite" implies that there is more than one piece of furniture, and the multiple pieces are coordinated in some way.

3. Nothing in this name implies anything about the method of manufacture though the problem statement clearly requires it.

After considering these shortcomings, we offer a second choice, "Disabled Chair/ Table Project," which has the following difficulties:

1. This name strongly implies two particular pieces of furniture, emphasizing those functions over the others, though nothing in the problem statement implied any more importance to these functions.

2. The word "disabled" may be interpreted to imply something about the people who will use the furniture.

3. Nothing in the name implies the severe cost constraint of selling for under $20.

Having tried these two names and found them wanting, we might turn to a third name, "Cheap Universal Furniture Function Project." We could carry the critical naming process further, but actually never find a perfect name. At some point, though, we'll stop and use what we have. Why? Because the important thing is not the name, but the naming. By going through the naming heuristic process,

1. we'll probably have a better name

2. we'll certainly have a better understanding of what our real problem is

3. we'll certainly do a better job of communicating our understanding to other people who join the project later

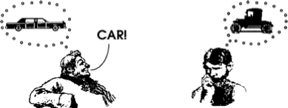

Even when thinking goes on largely in terms of pictures, the name is what gets transmitted first from one person to another. The people who receive the name will each reconstruct a picture of the name, and none of the pictures will precisely match what was in the first person's mind. (See Figure 12-3.) That's why we say:

One word is worth a thousand pictures.

Figure 12-3. A picture is transmitted through a translation into a name, which is then translated into another picture, once for each receiver. We say, "One word is worth a thousand pictures."

1. Although it can be a solitary exercise, naming things is definitely more useful as a face-to-face activity. In addition to achieving the given purpose, a face-to-face naming session has many side benefits. Early in the project, it offers a relatively innocent task as an excuse for the major players to get acquainted. If the players don't act as if it's an innocent task, then the session offers a preview of some of the political issues that may be smoldering under the surface.

2. When meeting to explore names, participants need a thesaurus and dictionary handy. The thesaurus helps generate new naming ideas, while the dictionary helps suggest easily be overlooked implications of the words.

3. Although a naming contest is an excellent idea-generating tool, plan for what you will do if you don't receive enough good suggestions. You'll generate bad feeling if you don't choose a winner, or if you announce, "There were many excellent suggestions, but in the end our beloved president gave us the winning entry."

4. One way to proceed is to choose a name and a subtitle. The name can be catchy, possibly an acronym or a word that suggests a nice pictorial symbol. It can even be a pictorial symbol. The subtitle, on the other hand, is the actual working title. For instance, our project might be called CUFF (for Cheap Universal Furniture Function: A Project to Hire the Handicapped).

Beware of too clever an acronym, though. In particular, beware of "backronyms," acronyms actually chosen for their cleverness before the individual words were chosen. If you start with a clever name and then force-fit words to obtain a working project title, you're almost bound to come up with an inaccurate, ambiguous title that will haunt you for the rest of the project.

If you're stuck, however, backronyming, can be employed as an idea-generating device. Start with some silly name and then use the thesaurus to hunt for words to fit both the initials and the actual meaning of the project. If the activity is playful enough, you just might discover something useful.

Names are used repeatedly, and they tend to steer the mind. If they are misleading or ambiguous, they become the starting point for trouble.

Any time a new project or subproject starts, or any time anything new needs to be named, the name must be chosen with care so as not to be ambiguous or misleading.

Follow this cycle:

1. Propose a name.

2. Offer three reasons why the name is not adequate.

3. Propose another name that eliminates these problems.

4. Repeat the naming process until you develop a usable name.

Don't go on forever looking for the perfect name. It doesn't exist.

The naming activity can be done by one person, but is best done face to face a group consisting of key participants in the project.