Camp Cooke

The special troop train was full, carrying 500 soldiers who had been in the Army Specialized Training Program at the University of Oregon. The 11th Armored Division, to which all of us were assigned, had sent officers, noncommissioned officers, and mess sergeants (cooks) to be in charge of our entire group. The mess sergeants set up kitchens in two baggage cars and fed us our meals en route. We even had a doctor on board who conducted daily sick call.

Our destination was Camp Cooke, California, an armored force base located near the Pacific Ocean, a little more than 100 miles north of Los Angeles. The route of travel was the reverse of the one we had taken to Eugene four months earlier. Having boarded the train in the early evening, we slept through southern Oregon and northern California, so missed the timber country. We did see Alcatraz and the Golden Gate Bridge as we came through the Bay Area. There were numerous shipyards and many ships docked at wharves.

On the train, army indecision reigned. The night we were to reach Camp Cooke, we had been instructed to go to bed by 10 P.M. Then we were awakened at midnight and told to get up and get dressed, as we were approaching the camp. After another hour and a half of catnaps, we finally arrived. As everyone climbed off the train we were greeted by a group of officers and noncommissioned officers from the 11th Armored Division.

The greeting party caught our attention by yelling through a loudspeaker. A lieutenant at the microphone was trying to be funny by telling jokes at 2 A.M. When we weren’t responsive, he began making nasty remarks about college kids and ASTP. It was all downhill from there. We were loaded onto trucks that took us to some barracks, where we showered, had a physical examination, and were given a snack.

Then we went to a gymnasium, where we milled about for four hours while some sort of classification process went on. At 6:30 A.M. they began to read off names and assignments. I anxiously sweated through name calls giving assignments to several battalions of armored engineers, ordnance, armored infantry, signal corps, and cavalry reconnaissance before they began to call the tank battalions. There seemed to be no system to the classifications, as air corps boys went to medics, medics went to infantry, artillery went to ordnance, and so forth. Very few of our friends were placed in the same units. My friend Shors and I were sent to the same tank battalion. Geiger went to a different tank battalion. At least Brig Young, who had trained as a medic, was reassigned to the medics.

The 11th Armored Division was a mixture of medium and light tanks that had participated in Louisiana maneuvers around DeRidder, the town where I was born. During my physical examination the night we arrived at Camp Cooke, the examining doctor commented on the fact that half of the uvula of my soft palate was missing. I told him that it had been inadvertently cut off while a doctor was performing a tonsillectomy. He asked where it had been done. I replied that it was in DeRidder, Louisiana.

His rejoinder was, “Looks like something that would happen in DeRidder.” It was rare for servicemen to develop a fondness for the communities near their base.

All of us newcomers were temporarily attached to Company D, a light tank company. It appeared to us that a tank company consisted of two groups. One group was the men in combat tank crews while the other group was the men who would provide services that would support the activity of the combat tank crews. The latter group included the mechanics, cooks, and supply personnel, who provided all types of supplies with the exception of food. The company commander was the highest-ranking officer in the company and gave direction to the first sergeant and the company clerk for administration of the company. He was also responsible for all training and combat activities of the company. After several days, the new men were assigned to their permanent company within the battalion. I was placed in Company B, a medium tank company that was still driving the Sherman tanks it had received when the division was activated at Camp Polk, Louisiana, two years earlier.

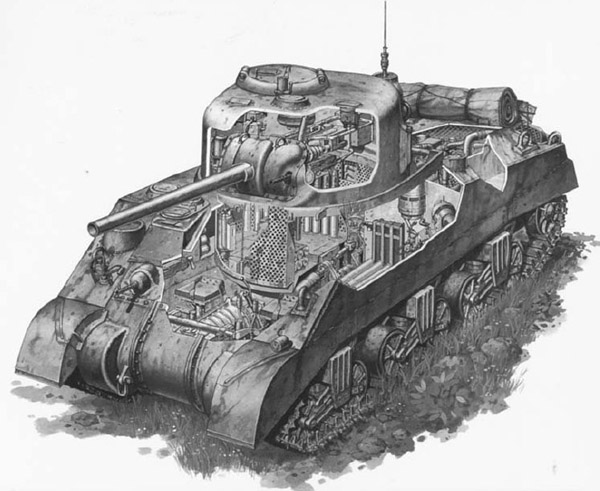

Cutaway of Sherman Medium Tank. Artwork by Peter Sarson from New Vanguard 3. Osprey Publishing Ltd.

There were two types of Sherman tanks in our company. One had a cast-iron hull and was powered by an air-cooled engine that had been developed for aircraft. In the other, the hull was made of two-and-one-half-inch-thick steel plates welded together. This type used a water-cooled 600 horsepower Ford engine. The latter was the preferred one. The same cast-iron turret was used in both tanks.

Our early impression was that the 11th Armored Division was a rough outfit. A number of the men in B Company spoke of escapades when they had gone AWOL (absent without leave) and had been court-martialed for the offense. When soldiers from the 11th went on pass, they were required to take with them an R & L Kit (a prophylaxis kit to be used for the prevention of venereal diseases). I never knew what the letters R and L stood for. This gives an idea of the main activity occurring on pass.

Many of the original men had been transferred out of the division to make positions for those of us from ASTP. The commanding officer of Company B, Captain Robert L. Ameno, interviewed the twenty-five new men individually and left us with a good overall impression. He told us that he would be making assignments after we had a couple of months of training, when he would have a better idea of our capabilities.

We were immediately immersed in classes and practical experiences to teach us the basics of how to function in an armored unit. We learned about each position in the tank. In addition, we learned the detailed duties of the position to which we were assigned. My first assignment was as an assistant driver. Although most of us were inexperienced, we were given lessons and training so that we could become proficient at driving a tank and firing the turret weapons. The assistant driver had a .30-caliber machine gun as his tank weapon. In addition, in combat, each member of a tank crew carried a submachine gun strapped over his shoulder for personal protection.

The Sherman tank had positions for the driver and the assistant driver at the lower front of the cast-iron or welded steel hull. Each of these positions had a hatch for entrance and exit. The round turret sat on the hull, to which it was attached by heavy metal gears. The turret had positions for three men—the tank commander, the gunner, and the assistant gunner. There were two hatches in the turret, one over the assistant gunner and one for the tank commander. The entire crew was connected by an intercom system. All members of the tank crew wore earphones and had microphones so that they could talk between themselves. Any communication to the tank by shortwave radio could be heard by every member of the crew. However, only the tank commander could talk over the radio to the other tanks.

From his position in the turret hatch, the tank commander was the eyes and ears for the crew of five, so he was required to keep his head out of the hatch at all times. In addition to coordinating the various activities, he gave instructions to the driver regarding speed and direction of travel. He guided the gunner to a target, estimated the distance of the target, and ordered the type of projectile to be fired. While he was directing these activities, he was also receiving instructions on the radio from the platoon lieutenant and/or platoon sergeant for his ongoing participation in combat. This all required major coordination during battle.

A 75mm gun was located in the center of the turret facing forward. The breech into which ammunition was loaded was at the rear end of the gun inside the turret. A .30-caliber machine gun sat immediately to the right of the 75mm gun. The gunner was placed to the right of this machine gun at the gun sight. From there he controlled the sighting and firing of both the 75mm gun and the .30-caliber machine gun following directions given by the tank commander. The assistant gunner sat to the left of the 75mm gun and loaded ammunition into it and the machine gun as needed.

The guns were mounted on a gyrostabilizer unit that floated the guns and kept them aimed at the sighted target even when the tank was moving across uneven or irregular ground. This allowed our tanks to fire either gun with accuracy while on the move, something the Germans could not do. In order to be accurate, the Germans had to stop their tank to fire the large guns. Also, the turret on most German tanks had to be rotated by a hand crank, whereas our gunner could rotate the turret 360 degrees with an electrical control switch.

In an early letter written to my parents, I asked, “Can you imagine me as a tanker? I always thought that Son [my brother] would be more the type of person to be in a combat outfit because he is so well coordinated. However, I am sure that I can take anything that they throw at me.”

The letter continued, “Right now I am at the Service Club catching up on correspondence. All of the older soldiers in the company tell us to clear out of the barracks as soon as you are off duty and don’t come back until bedtime or you will be chosen for some sort of extra duty. This was good sound advice that we learned to respect and follow.”

The 11th Armored Division had many little quirks we learned to accept. We were required to wear only army-issued shoes when on base. Civilian shoes were forbidden even if we were off duty but on base. Civilian shoes could be worn only when we were off base and on furlough. The wearing of a garrison cap (cap with a bill) was not allowed. The cloth overseas cap was the only head cover permitted. Soldiers in most army branches wore their cloth caps tipped to the right. Not so with the armored soldier, who wore his cap (often with the taller Fort Knox peaks at the front and back) tipped at a rakish angle to the left. The army-issue cloth cap had a peak at the front and back which was created by the head fitting into the flat envelope-shaped hat. Fort Knox peaks were an accentuation of this peak at the front and back, created by a deeper envelope. Fort Knox was the official home base of all armored activity in the army and was the original site where the high-peaked cap was worn.

Two weeks after we arrived at Camp Cooke, we were told that we would be required to have the 11th Armored Division patch sewn on the sleeves of all our uniforms by the following Saturday, which was three days later. These patches were usually available from the supply sergeant free of charge, but he had none. An order was an order, and it did not matter that there were no patches available on the entire base. So we scurried around and arranged for some of the men who were going to town on pass to buy patches for us at the local army store. These privately owned stores were in all towns near army bases and usually carried all sorts of supplies in addition to army goods. The trouble was that the patches cost 25 cents each. With ten items requiring patches, that meant we had to spend $2.50. What a rip-off.

After four weeks of basic armored training, we were tested in driving skills, principles of reconnaissance, guard duty, and poison gases. We had to identify the poison gases by smell. It wasn’t hard. Some of the lewisite spray hit my face, though, and made tiny little stinging blisters. We passed all of the tests in good order, so we began to have field exercises in which we were taught general combat tactics.

As we gained a better understanding of ways to manage ourselves in combat, we began to engage in tactical exercises using the tanks. Our old tanks were filthy inside because of their previous use in desert training. Each of us was assigned used equipment that all tankers were required to have, including goggles, cloth helmets, and gas masks. The gas masks had also been used in desert training and were really filthy and crusted on the inside.

The motor park where the tanks and other vehicles were kept was across a perimeter road from the barracks area. We would march there and back at least twice each day. As an assistant driver, I had to learn to drive the tank so I could relieve the driver as needed. There was a hatch door overhead for direct entry and exit. When we finished field exercises, we would come back into the motor park and perform the necessary maintenance. As we helped maintain the tanks, we began to learn more about them and how they worked. After we became more experienced, we were allowed to drive the tanks back to the motor park from the field.

Even though we ASTP types were the youngest and least experienced men in the company, we were gradually gaining acceptance. One of the officers took us out for driving lessons to a spot about one-and-one-half miles west of camp and there it was, the Pacific Ocean. Now we understood why we battled incessant winds and blowing sand. The driving lessons were catching our interest, even though we did them in tanks that were dusty and dirty. They were really powerful old buggies that took two gallons of gas to go one mile. Because they were so old, they also broke down constantly. It kept the mechanics extremely busy.

Driving a tank did not turn out to be as simple as driving a four-wheeled vehicle. It took many lessons before I was able to coordinate gear shifting in a vehicle which weighed thirty-three tons. The gears didn’t mesh smoothly, so shifting gears required double-clutching and a lot of beef. Our tank was powered by a Continental radial air-cooled engine which had been developed for aircraft but had been placed in many tanks when other engines were not available. Potential for stalling was ever present if the required number of revolutions per minute was not maintained. While concentrating on that, one had to keep control of the steering levers. The driver steered the tank by pulling a right or a left lever or, if braking, by pulling both levers simultaneously. It simply took experience at the controls to develop the coordination required.

Not until some weeks later was I given my first opportunity to drive the tank during a mock battle where we took an “enemy airfield.” It was a major triumph and was, I believe, the beginning of my acceptance as part of the team. I didn’t goof up, so that was a major accomplishment. After getting to know the boys better, I realized that they were a good group. There was a large contingent from the East Coast, but there was also a good spread from across the country.

In a letter to my parents, I described some of my buddies who also slept on the second floor of the barracks. Those descriptions are as follows:

Leonard Montkowski is a private, is hard working and a good kid, but has never been willing to swallow some of the stuff necessary to get a promotion. I enjoy him.

Pat Needham is an Irishman, about twenty-six years old. He has had three years of college and is a devout Roman Catholic, attends mass regularly. He was just promoted to private first class and is very disgusted with that because he considers it barely more than a private. He is bright and very interesting.

Patrick McCue was in ASTP at the University of California and has had two years of college. His home is in San Jose. He is getting married soon to his college girlfriend. Very nice and likable. Humorous without intending to be.

Thomas Sumners (nicknamed Paducah) is from Kentucky. There are no secrets from Paducah. He watches and asks and needs to know everything. He is interesting. We go to chapel together.

John O’Loughlin from Utah was also in ASTP at University of California. A good boy.

Bill Zaher is a sergeant tank commander from Chicago. Has a fine sense of humor and is well coordinated. Reads good literature.

John Myers is a chubby sergeant and tank commander from Ohio. His father is a Methodist minister in Steubenville. He is very likable and has a good sense of humor.

All in all, this is a very interesting group.

Several weeks after arriving at Camp Cooke, a one-time event occurred. We had a weekend visit by 120 Junior Hostesses from Los Angeles who came to visit our battalion. They stayed in the barracks next to ours, but there had been a transformation. All of a sudden we noticed curtains and other nice touches not usually seen in army barracks. We had a dance at the Service Club Saturday night and took them to chapel on Sunday morning followed by rides in jeeps and tanks. Sunday afternoon they departed and we returned to normalcy. They were a nice sociable group, even if, as I wrote to my parents, they were not all “ravishing beauties.”

By early May, we had completed training in firing carbines, submachine guns, .30-caliber machine guns, and .50-caliber machine guns. The latter was located on top of the turret and was used to fire at enemy aircraft. This completed instructions required by the Army Ground Forces before we were qualified for overseas assignment.

Thinking that I would go to medical school after getting out of the army and that working in the medical corps would be good experience, I visited our battalion medical officer to discuss the possibility of becoming a medic. He told me he had never been able to get the Company B commander, Captain Robert L. Ameno, to agree to transfer a man to the medics, but he would try. So he put in a request to have me transferred, only to have the request denied. Captain Ameno then called me into his office and told me that he did not approve the transfer. He told me that as a medical corpsman, I would be out in the middle of the battlefield without a weapon to protect myself. He thought such an experience would be of no help to a future doctor. I respected his opinion and dropped the matter. After going into battle and seeing our medics riding in open jeeps out in the battlefield without weapons, I shall forever be grateful to Captain Ameno for his wise counsel and help.

As our education advanced, we acquired more and more field experiences. We went on a road march in the tank to learn how to keep up the pace with eighteen tanks moving at the same speed and arriving at the target area at the same time. From a beginner’s standpoint, it was actually fun. I was still in the assistant driver’s seat and became acutely aware that the tank engine was drawing air through vents in the front of the hull. I quickly learned that tanks were cold when it was cold outside and brutally hot when the weather was hot. The country where we bivouacked on that outing was very pretty even though semiarid and covered with scrub oak. It was away from the Pacific Ocean, so it was much warmer than it was at our barracks. Each of us had to walk a two-hour guard shift around our individual tank, a practice strictly adhered to on maneuvers and in combat.

Home on furlough in Ames, Iowa, May 1944, from Camp Cooke, California, Ted Hartman visits with parents and sister.

I was in line to get a ten-day furlough to visit home, so I needed to buy a nice pair of shoes that I could wear off post. I was given a ration coupon which allowed me to purchase one pair of shoes. I went to the Officers Post Exchange and found a beautiful pair made of very fine soft brown leather. They cost $7.45, more than I had hoped, but I was able to sell my old pair of brown shoes for $4.00. I figured that I could get at least $3.45 use out of the new shoes. This gives an idea of the value of the dollar in 1944.

I received a ten-day furlough in the latter part of May 1944. An ordinary soldier could only afford to travel by coach on the train. I boarded the train in Santa Maria and went to Los Angeles. The Union Pacific Railroad did not accept seat reservations on most trains, and when I boarded the train in Los Angeles, all of the seats were taken. So on the overnight trip from Los Angeles to Denver, I had to choose between standing in the aisle or sitting on the armrest of an aisle seat. I chose to sit. Many of the passengers left the train at Denver, so I was able to get a seat for the remainder of the trip to Ames, Iowa, my destination. Most of the time on furlough was spent with family, as all of my male friends were away in the service. My sister was home on vacation from Washington, D.C., where she worked as a cryptographer for the army, coding and decoding secret messages. Using some rationed gas, we drove ninety miles to visit an aunt and her family.

At the end of the furlough, I boarded a Union Pacific train car in Ames that was a real puddle jumper. However, at Omaha, I was able to get a reclining seat in a nice coach. While we were at the depot in Denver, someone took my suitcase to the men’s lounge and rummaged through it. It mysteriously reappeared on the rack over my head with nothing missing. The connection in Los Angeles to the Southern Pacific train for Santa Maria was close, and I had to rush to get a seat. As soon as the train pulled out of the station, I went to the diner and enjoyed a very nice dinner for 75 cents.

When I arrived back at Camp Cooke, I found that a number of men had been transferred to the infantry, including our first sergeant. My platoon sergeant, Lenwood Ammons, was named first sergeant. That pleased us, as we had great respect for Sergeant Ammons. Also, I found that I had been promoted to private first class. As mentioned earlier, being promoted to private first class (PFC) wasn’t much of an honor. In a letter home, I told my parents of the appointment and that I wasn’t thrilled about it and did not want them publicizing it. The local newspaper always published any news about men from Ames who were in the service, and I knew my folks would inform the paper. Though I did not want the appointment, I feared that if I refused it, I would have a hard time ever getting a promotion higher than that, so I kept quiet.

After I returned to Camp Cooke from furlough, the “old man,” a classic army term used to refer to the commanding officer, called me in and asked me whether I preferred to be a gunner or a driver. I told him that I thought I could handle either position so would do whatever he thought was best. Several days after that, our platoon sergeant called me over and told me that I had been appointed as his driver.

In early June we went out on a night blackout march. After sitting around the motor park all afternoon and evening until 10 P.M., we finally moved out on the march. Needham drove and I was in the assistant driver’s seat. I hadn’t driven enough to try the night blackout march. It was very difficult to see the very small dim red taillight on the tank in front of you, especially with swirls of dust between it and you. It was a good experience, though, and the following morning we were assigned a new objective.

After securing the objective, we went back to the motor park, where we performed first-echelon maintenance such as filling the gas tank, greasing the bogie wheels, and so forth. (Bogie wheels are made of metal and have rubber padding on the outer surface. They are the small supporting wheels that roll on the inside of the track as it is laid on the roadway. They are part of the suspension system of the tank.) We were working away when all of a sudden we heard a loud explosion. We ran over to the Company C area where we had heard it. There lay a lieutenant in front of a tank with his left arm torn off below the elbow. Also, his left side was badly injured and peppered with shrapnel. They called the medics right away, but by the time the ambulance arrived, the lieutenant was already dead. It was a horrible sight.

The lieutenant had picked up a shell out in the field which he thought was an armor-piercing shell, but it had turned out to be a high-explosive shell. Armor-piercing shells burn their way through the steel hull and then explode, whereas the high-explosive shell, even when jarred, can explode and release bits of shrapnel in all directions. The lieutenant was completely to blame, as we had been repeatedly warned not to do just what he had done. Even so, it should not have happened.

In July, we were assigned a one-day simulated battle to execute. It was my first experience at driving in a field exercise. The fact that the company commander had assigned me as a tank driver caused some concern among the men with longer experience in the company. Their thought was that by rights such positions should go to the older men who knew tanks through and through. I understood their concerns. However, I thought that those men who hadn’t advanced in rank after two years of experience would not likely be chosen for those positions. I was determined to try my hardest to justify being named a driver and at the same time be considerate of their feelings. It worked.

With all of the events that were happening at this time, I wrote to my folks, “We are getting new men all of the time now. It makes us believe that we will be going over before too much longer. If we do go overseas and I get ‘bopped off,’ you are entitled to six months of my pay plus all that they owe me at the time, but you have to apply. Please remember this.”

A little later I was assigned to a detail to build waterproof boxes in which to pack our machine guns so they could be returned to a supply depot. We were to receive new ones with new tanks overseas. The next day, we worked for hours painting the tank and getting it ready to turn in within two weeks. Something was surely going on.

The pace began to speed up. In the first week of August, we were restricted to the base, and our classes and duty hours were extended to 9 P.M. Some of the sessions were set up for us to receive new equipment. We turned in our shoes and received new boots in exchange. The boots were strange looking. In the typical boot, the leather on the outer surface is smooth and the leather on the inner surface is rough. These new army boots were the opposite of that with smooth leather on the inside surface and rough leather on the outside. There was a consolation, though. We couldn’t be given a demerit, since it was impossible to shine the rough leather. As it turned out, the rough leather on the outside was a perfect sponge for water, which was not so good in snow and wet weather. We also received new tanker overalls, cloth helmets that had a strap that snapped under our chin, new fatigue suits, and new metal helmets and plastic liners.

Then we began to have classes on reading French and German maps. We were taught some spoken French and a small amount of spoken German. Pat McCue’s new bride was working in the post quartermaster, and she told Pat that our orders had been received. We would soon be moving to a port of embarkation near Boston or New York City. Our new tanks had already been sent to Camp Shanks, New York, where an advance party from our division took delivery of them and arranged to have them sent to a seaport for shipment.

For some time, several of us had been hoping to get a pass to go to the Army Rest Camp on the coast of the Pacific Ocean at Santa Monica. One weekend, four of us unexpectedly received passes plus transportation in the back end of an army truck. It was not the most comfortable way to go, but it was inexpensive. We arrived in Santa Monica in the early evening, checked into the camp, and decided to go to the Hollywood Canteen to see what entertainment was going on. One of the most sought-after orchestras in 1943 was Kay Kyser’s orchestra, and there they were. What a treat for us! Since none of us was 21 years old, we were only allowed to buy nonalcoholic drinks.

Following that, another celebrity, one of the singing King Sisters, entertained us. One of our group, Wayne Van Dyke, was able to arrange dates for us, so after we left the Hollywood Canteen, we picked up our dates and went to Casino Gardens, another hangout for servicemen. Some band that we had never heard of was playing when we arrived, but all of a sudden things changed. We looked up and another extremely popular orchestra, the Harry James Orchestra, was playing. Boy, could Harry James make that trumpet perform! We could hardly believe our luck that night. Four very tired but happy soldiers returned to Camp Cooke on Sunday night.

The pace toward our departure continued to quicken, and in early September we left Camp Cooke for a port of embarkation.