The Ambush at Noville

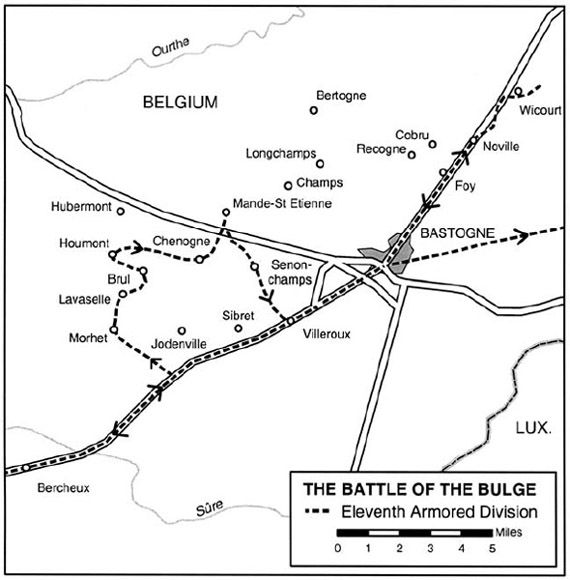

After rest and recuperation in Bercheux, Belgium, we were ordered back to the battlefront on January 12th, 1945. By this time, the battle line was slightly north of Bastogne, not far from where it had been when we were relieved nine days earlier. Our orders were to move north to the village of Villeroux. There had been more snow and freezing rain and the roads had become extremely icy, so our tanks were sliding in all directions. It took us fourteen hours to go eight miles.

The following day we moved through Bastogne and stopped for the night south of Foy near the IP (Initial Point, the point of entry into battle the next day). After a supper of cold C-rations and a cup of hot coffee made on the little stove in our turret, we set up the guard schedule so that each member of our crew would take a two-hour turn during the night while standing in the tank commander’s hatch. Each of us “slept” while sitting in the seat we normally occupied. This was the usual sleeping arrangement when in dangerous territory.

In freezing weather, nothing can be colder than a tank with frost forming over the interior of the thick steel walls. Many of us had frostbitten feet from being out in the cold and damp for prolonged periods. During the Battle of the Bulge, this was a common problem, causing a large number of soldiers to be evacuated to hospitals in the rear for treatment. We developed our own method of managing frostbite by cutting a wool army blanket into strips three inches wide and wrapping our feet with these when we were not actively fighting. We wore the army-issue galoshes over these strips. This helped, as we could change the wrappings every few hours to keep our feet dry. Following an urgent request, my parents sent me a pair of felt boots to wear inside the army-issue galoshes. That was the best solution yet.

When battle plans were drawn for our attack on Noville, troops of the 101st Airborne Division occupied the village of Foy. However, on the night of January 13th, the 101st had been driven out by a strong German counterattack. Because of this, recapturing Foy became our first objective on January 14th.

For fighting on the 14th, Company B was detached from its usual line of command to the 41st Tank Battalion and was assigned to serve under the 21st Armored Infantry Battalion. Armored infantry were not typical foot soldiers, as they rode in lightly armored half-track trucks. They fought from the half-track, which was an open truck with wheels in front for steering while on each side of the back there was a track system instead of wheels to propel the vehicle.

The plan was for Company B to assume the point for battle the morning of January 14th with the 21st Infantry supporting. The fighting had gone well, and we had taken Foy by early afternoon. From there, we began our attack on Noville with the 21st Infantry at the point and the tanks of Company B supporting. We were in line formation, side by side, backing up the infantry and firing continuously into the Germans, who were on high ground near Noville. They were returning heavy fire from mortars as well as from tank and antitank guns.

Some of the German tanks had the extremely high-velocity 88mm guns. The guns on our Sherman tanks were the much slower 75mm guns that produced less than half the velocity of the German guns. In addition, the explosive force of our projectiles was considerably less than that from most of the German weapons. We had learned that we would almost always lose one and often two Shermans in battle with the heavier German tanks, as their high-powered guns could penetrate our tanks from any angle. Because the hulls of the German tanks were thicker on the front and sides, the only way we could disable them was by firing into the tank’s rear.

We were taking a toll on their foot soldiers by firing our .30-caliber machine guns and were slowly but steadily gaining ground. Our armored infantry then tried to make an attack in half-track vehicles but were quickly repulsed by intense fire. The German 88mm guns hit three of the vehicles instantly and set them on fire. One soldier had gotten partway out of the half-track when he was caught. He lay there burning. I almost lost faith in humanity; that was the most appalling sight I had ever seen.

Now we had to get that gun, the one that hit the half-tracks. We disabled the German tank by steadily firing our large guns, but not before it knocked out one of our tanks. The German gun had fired an armor-piercing projectile that entered the turret, killed all three men, and then exited the other side. We knew that the German 88 was extremely powerful, but this was devastating for us to see. We were later able to measure the distance from which it had been fired—1,700 yards, almost one mile!

There were dense forests facing us, good for the German defensive action but not easy for the offensive fighting that we were doing. By later afternoon, we had fought our way to the southern edge of Noville. Because winter days are short in northern Europe, dusk was upon us even at 4 P.M. We moved into a defensive position just outside of Noville and were organizing for the night when our acting company commander received an order by radio from the commander of the 41st Tank Battalion to rejoin them by proceeding through the objective to the high ground on the other side of town. When talking on the radio, we did not use proper names, such as Noville, but used nouns such as the objective that would not give away our position. To our front was the village that had been fiercely defended by the Germans all afternoon. It seemed very strange that we could now simply drive into town.

But an order was an order, so after considerable reluctance on the part of our officers to make such a move, particularly after dark, we assumed a column formation and started into Noville. We followed the acting company commander as his tank started up the narrow road. There were destroyed buildings and disabled German tanks and vehicles everywhere we looked. I was the driver of the fourth tank in the column. It was getting dark and hard to see, so I was driving with my head partway out of the hatch. There was a church on our right and a small crossroads just beyond it. As we passed the crossroads, I saw the burning phosphorus of an armor-piercing shell go over my head. Were we in enemy territory?

All of a sudden, someone on the radio said, “The tank of the third platoon leader’s been hit.” That tank was the seventh in our column of twelve. (The normal fighting complement of a medium tank company is seventeen, but in the preceding two weeks, we had lost five of them in intense fighting.) The tank that was hit was now burning and completely blocking the road. This meant that the six tanks in front could not retreat by that route. The five tanks following were able to back out of town.

The first six tanks moved forward on a road to the left and coiled in an apple orchard, much like the covered wagons of the old West. All of the tanks maneuvered to face outward and be in position to protect each other from the rear. By now, we had reached the high ground on the other side of the objective, but it wasn’t the right objective. Two of our tanks were hit and disabled just as we coiled. Crew members from those tanks jumped into the turrets of the other four tanks. Two men jumped into our tank. By this time, I had closed my hatch and turned the periscope to look back toward town. I saw many German soldiers filing out of buildings. They were wearing those awful, ugly German helmets.

There was a rash of radio talk. Conversations went back and forth between our acting company commander and the battalion commander of the 21st Armored Infantry, under whose command we were fighting that day. Our acting company commander seemed to be at a loss to decide what we should do next. My platoon leader was so upset that he lay down in the snow and kicked his feet against the transmission of his tank. We later learned that the commanding officer of the 21st Infantry had planned to send some troops in to rescue us, but his communication with our company officers was so confusing that he dismissed the plan.

The assistant driver of the platoon lieutenant’s tank was sent out on reconnaissance. He discovered a large number of German soldiers advancing on us with bazookas. The acting company commander decided that we would all start our engines at the same time and each tank would then take off and get back to our own lines the best way we could. We started our engines. The minute they started, the Krauts began firing. All hell broke loose, but through the grace of God, our tank wasn’t hit.

I was driving. It was dark. Because the driver’s view of the world is unusually restricted in the dark and when using the periscope with the hatch closed, the tank commander usually guides the driver by communicating over an intercom system. However, he failed to give any instructions to me, the driver. I could barely see. The next thing I knew, our tank had dropped into the sunken foundation of a burned-out house. It was not possible to maneuver it out.

We piled out of the tank. Once out, we hid beside a hedgerow away from the tank while we considered what to do. Our platoon sergeant was so upset that he was unable to make any decision. One of the other men and I decided that the best plan was to parallel the road on which we had come into Noville, but at a distance.

Just then, we heard footsteps. We quickly ducked. It turned out to be someone halfway running and crying, “Please don’t shoot. I am an American.” It was one of our men, Eugene Baudouin, who was gunner in the acting company commander’s tank. His eyes had been badly burned when the turret of his tank had been hit by a bazooka, and he could not see.

We hunkered down against the hedgerow to be certain it was safe for us to start out on foot. All looked clear, so we started toward our lines. We had only gone a short distance when I looked back and saw Baudouin trailing behind. It was clear that without our help, he would not be able to keep up with us. Yet if he slowed us down too much, we could be captured by the Germans.

Actually, there was no choice. Just as we would hope to be helped if the situation were reversed, we realized we must assist him back to our lines. A couple of us dropped back to help, as he had gotten so weak that we had to half carry and half drag him. We hiked and crawled through the snow-covered fields and fences, forded a small river, and climbed a steep hill. We finally asked the others for help with Baudouin. After what seemed an eternity, we began to approach what we hoped were the American lines. We saw a farmhouse and heard voices. We immediately dropped to our knees and strained our ears. We heard the expression “okay” and hoped it was our troops talking.

Each evening at dusk, for security’s sake, the password for that night was transmitted to us person to person, never by radio. Since we had left our lines before receiving the password, we were concerned that we might not be properly recognized. In the Battle of the Bulge, the Germans had dressed many of their English-speaking soldiers in American uniforms and had infiltrated the American lines to create confusion. We were concerned that we might be mistaken for those Germans.

We spent a few minutes thinking of American names such as Bing Crosby, Joe Louis, and Frank Sinatra. We also thought of words that are hard for the Germans to pronounce, such as words ending with “th.” For example, when Germans speak the word “with,” it sounds like “witt.” When we got within hearing distance of a guard, we called out and approached very cautiously, saying everything that we could think of that was American.

When the guards saw us they called us to advance and be recognized. We went forward. The guards were men from the 101st Airborne and had been informed that we might be coming through. They had been told not to insist on the password. We were all pretty emotional at that moment of recognition. We were back among our own.

But we still had to take care of Baudouin. He had asked that I stay with him, so I promised that I would. The Krauts had mined the road, so we were not able to walk on it to reach the battalion aid station. Just at that moment, the commanding officer of the 21st Armored Infantry, Major Keatch, came by in his tank. He stopped and offered to take Baudouin and me to the battalion aid station, so we rode to the medics on the rear deck of his tank. At the aid station, Baudouin received first aid care. He was evacuated to England and then on back to the States for treatment. He completely regained his eyesight. I heard from him a time or two after the war and then lost track of him.

At the battalion aid station, I ran into our first sergeant, Lenwood Ammons, who had come there hoping to find out what had happened to all of us. He found the acting company commander and the platoon lieutenant receiving first aid. Both were evacuated to the rear echelon to receive further medical care.

I went with Sergeant Ammons to the farm near Bastogne where our maintenance crew was staying. Some of the 101st Airborne Division boys were also there. They really fed me and treated me royally that night. Our mess sergeant even gave me his PX rations (candy, toothpaste, and soap). By this time, I had no possessions except for the clothes on my back, so they provided me with everything I needed.

In Noville that night, in addition to the crews of the six tanks in front of the disabled one, there were also three members of the crew of the tank that had been hit. Two of them, Lorence and Leslie, had been injured. So the third member, Wayne Van Dyke, took the two away from the burning tank where they lay on the ground awaiting our medics. They thought the American infantry controlled the town until they saw a group of German soldiers walking toward them. They played dead while the Krauts stopped directly in front of them. They lay there, barely breathing, until they heard receding footsteps. At that point, they realized that our medics would not be rescuing them. As light from the burning tank began to die down, Van Dyke and Leslie helped the more severely injured Lorence over the church wall and into the church. Lorence felt certain that the wounds of his feet and legs would prevent him from crawling back to the American lines, but he encouraged the other two to make the try. After much soul-searching and hesitation, Van Dyke and Leslie decided to make an attempt at getting back. Leslie had major wounds, so it was with great difficulty that he and Van Dyke crawled and walked to make their way back to the American lines. At one point, Van Dyke even had to carry Leslie on his back.

The German medics dressed Lorence’s wounds twice that night. They knew that they would be retreating from Noville the following morning, so they told Lorence that they would leave him to the care of his own medics. The following day, Lorence was found by American soldiers and picked up by medics.

On that fateful night, two of the men from our company, Sergeants Francis Woods and Gordon MacKinney, borrowed a jeep and went into the German-held town looking for Lorence, Leslie, and Van Dyke, but they couldn’t find them. These are the unsung heroes of the war. Wayne Van Dyke was awarded a well-deserved Silver Star. Bill Zaher was the commander of the only tank trapped in Noville that was able to make it back to our lines that night. One of the tanks behind the burning one was disabled when it backed over a land mine. Of the twelve tanks that entered Noville, only five were left after that night.

Tanks that were disabled in battle were recovered by use of a T2 recovery vehicle of the 11th Armored Division’s 133d Ordnance Battalion or by a Third Army Tank Recovery Battalion. They were brought to a tank recovery installation where they were examined and repaired when possible. It was the army policy not to return a reconditioned tank to its original unit because of the possible negative connotations it might have for the previous crew or unit. For that reason, we never saw Phikeia again.

My feet were really bothering me by this time, but I was keeping them dry and wrapping them with the wool blanket strips and they were improving somewhat. All of that day, January 15th, I spent just sleeping and resting. I had almost acquired “war nerves.”

The next day, the first sergeant found other men from our company and brought them to the barn where we were staying. He told us that ordnance had brought up new tanks for us and that we would be sent back to the front the following day. The platoon sergeant, who was commander of the tank I had been driving, and two others from the turret crew of our tank became frightened when they heard we were to be sent back to the front. They went to the medics with “frozen feet.”

Sure enough, on January 16th, three new tanks arrived to replace some of those we had lost in Noville. These had the much-improved 76mm gun that we had all wished for. And, yes, we were sent back to the battlefront. At the time, it seemed like a very heartless thing to do. I later realized that it was better for us to get back to duty than sit around with our fears.

By this time, we had lost so many men with tank commander experience that I was designated to be commander of one of the new tanks. The driver who was assigned to my tank had previously only driven one when we were learning to drive tanks back at Camp Cooke. That was a bit disconcerting. At least he had seen battle and had some experience in tank warfare. I was delighted to have Hoppie Langer assigned as gunner. He was considered to be one of the best gunners in our company. That was a big plus. We named the new tank Eloise II after the driver’s girlfriend. The first Eloise had been hit and destroyed in earlier battle action.

In tank warfare, the commander must keep his hatch in the top of the turret open and serve as the eyes and ears for the entire crew of five. So, in preparation for the return to the front, I lowered my helmet as much as possible and wrapped my overcoat around my neck. You could barely see my eyeballs. We three crews with new tanks drove up to the battlefront and rejoined our company. We pulled up in line with the five tanks that remained of our original company, which by that time were a few miles north of Noville.

We had been there about five minutes when an artillery shell landed on the right front track and sprocket of the new tank. Shrapnel from the shell tore the overcoat wrapped around my neck. I even found a piece of it in my overcoat pocket! With that welcome back, I closed the turret hatch door and called the newly named company commander, Lieutenant Grayson, on the radio. I requested permission to go back down to the driver position and asked if he would send someone over to command the tank. Presently, there was a bump on the turret hatch and in jumped Lieutenant Ready as our new tank commander. Ready had been a sergeant in our company and had received a battlefield commission. We respected his battle ability.

Although the commander of the 41st Tank Battalion knew that Company B had been detached from his command the day of January 14th, that fact was obviously not registering when he gave the order for us to come through the objective to the high ground the other side of town. Since Company B was under a different command that day, it would be highly unlikely that it would have had the same objective as the remainder of the battalion.

So it was that through an error of communication, we drove straight into an ambush and were shot up by the German army. Those of us who survived are grateful that somehow we were spared, perhaps by some higher power.

That’s the story of the ambush at Noville. I might add that only one of the tank crew that I was in and two of the company officers who left us after Noville returned to the company to participate in later combat. That crew member returned long after we crossed the Rhine River.