Release of Concentration Camp Prisoners

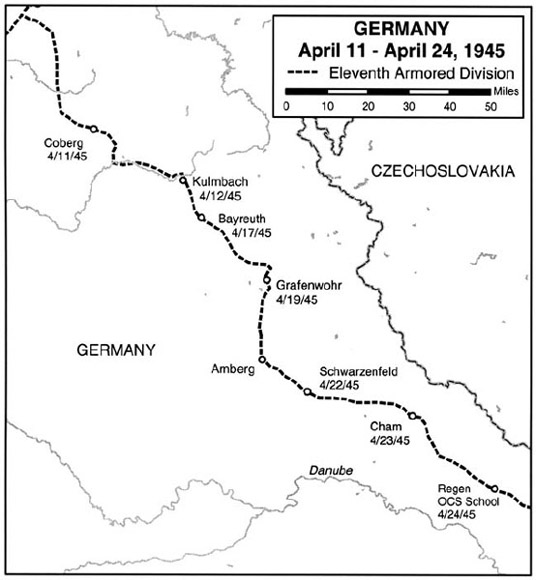

After spending the night in Amberg, we were ready to move out by 8 A.M., but suddenly we were told there would be a delay of several hours. By now we were in east central Germany, where we were meeting more resistance. Often we had such delays and rarely knew why. We accepted the fact that it was usually for a good reason, perhaps even our own protection.

About mid-morning we finally started moving at a good pace with very little opposition. The countryside was heavily wooded and hilly, the type of topography where tanks can get ambushed if they are not on the alert. As we were passing through one village, the townspeople told us that SS soldiers were in the woods on the other side of town. After we shot up the woods with machine guns, we learned that the rumor was false. We had long since decided to take no chances, so we were doubly prepared.

We assumed that many of the men from the villages that we were entering now were serving in the German armed forces, as the inhabitants seemed to be mostly older women. Tanks are very noisy, and their image engenders fear. Our entry into most of the villages was a surprise, so many of the women were crying, presumably frightened about what our tanks or we might do.

We moved on and stopped just after crossing a small river so that our artillery could leapfrog and be in a position to support us. Once they were set up, we moved out again. We did not have detailed maps of this area, and we took what looked like a satisfactory route, only to find ourselves on an unimproved road going down a steep mountain pass. It began to rain and then to pour. One part of that road proved particularly bad. It was unpaved and muddy, which caused the track treads to lose grip. Sliding downhill in a 33-ton vehicle sideways as well as forward can be pretty exciting, but we made it to the bottom without a major catastrophe. After finding an adequate road, we passed through several small mountain villages and finally reached good paved roads again.

Soon we came across an empty concentration camp, which we learned from the radio had been occupied by Polish prisoners. From a distance, we could see the German guards fleeing. We knew that we would catch up with them eventually, as we were moving at a very fast pace. Continuing our drive, we took an excellent road and went about two miles, only to discover it was the wrong road. This was one of those days when new maps had not reached us. However, we captured several Krauts, so the gas wasn’t wasted.

After getting turned around, the tank column started toward the city of Schwarzenfeld, about five miles away. As we approached, we could see that it was teeming with German soldiers. Moving into town, we found Krauts and their army vehicles, mostly trucks, everywhere. They offered no resistance but surrendered voluntarily, so we sent them to the rear as prisoners of war. Our column stopped while reconnaissance checked “the deal over the blue” (radio talk for bridge over the river). We were at the Naab River, which runs into the Regen River, which in turn flows into the Danube.

I was still the tank commander at this time. It was here in Schwarzenfeld that a Kraut truck pulled in behind our tank from a side road, thinking he was joining a column of German army vehicles. He was really shocked when he looked up and realized that he was behind an American tank. He and his comrade quickly jumped out of the truck with their hands over their heads. We searched the truck and found three pistols and other military paraphernalia.

One of our German-speaking soldiers ordered the two Krauts to go down to the bridge that lay ahead. Then we advanced toward the river and found six German soldiers in a guard house at the bridge, which, as it turned out, was wired with enough dynamite to blow us sky high. We interrogated the prisoners and learned that the mission of the truck that had pulled in behind us was to come to the bridge, pick up those men who had wired it with explosives, cross the bridge, and blow it up from the other side. However, they never got the chance. Had we not discovered the information about the bridge from the German soldiers, we could very well have been on that bridge when it blew up.

It was essential for us to be constantly on the alert for any little nuances in information. Such knowledge could easily mean the difference between life and death. This was a never-ending process at this stage of the war.

Our platoon was at the head of the column this day. We moved up the road a short distance and stopped at a point that had a commanding view of Schwarzenfeld. Two very fine highways led from the city; one was an interurban road and the other led to a nearby village. All of a sudden, our gunner, Hoppie Langer, through his gun sight saw an enemy column pulling out of a village several miles to our right. We radioed the other tanks and then shot up the whole column. It was a very odd assortment of trucks, horses, wagons, and foot soldiers. Next, we set fire to the village with incendiary shells. Then we turned our weapons to a huge house to our right front and set it on fire. Masses of Krauts fairly swarmed out of those burning places with their hands over their heads. We motioned them to the rear to be picked up as prisoners of war. The military police maintained a collecting center for prisoners of war at the very rear of our column that we called a POW cage. Those of us in the fighting column never saw it, but knew about it and of the reputation it had for effective management of prisoners of war.

We camped just outside the southeast part of Schwarzenfeld that night and kept hearing Kraut trucks pulling into our lines; they did not know that we Americans had advanced this far. The following morning our orders took us out of town to the southwest, so we didn’t get to see our “handiwork” from the night before.

We continued to move through forested and mountainous terrain; our first big objective on this morning, April 23rd, was Neunberg. As we approached the town, we received word that 1,200 Hungarian soldiers who had fought with the Germans wanted to surrender to us. Just beyond town, we found them. They had only horse-drawn wagons, no motorized vehicles, and none of the better equipment that the German army apparently reserved for itself. They were a pitiful-looking group who seemed to be relieved to surrender without a battle. We sent them to the rear of our column where our military police awaited them.

From Neunberg, we headed south and were at the point of the column, progressing nicely, when a report flashed over the radio that thousands of refugees were coming our way. A little farther on, we saw a number of brown-skinned people crawling in the woods. At first we thought they were Krauts, but they did not appear to be German and were wearing odd-looking striped suits. As it turned out, they were the first of countless thousands of political prisoners we were to free that day. They had been prisoners at the Flossenburg and the Buchenwald concentration camps. We began to come upon huge numbers of them on the road. They were really holding up our progress and would not get out of the way before they had expressed their thanks in one way or another. Their joy was absolutely unbounded, and even though they were emaciated, they were cheering and waving madly.

There were 16,000 people from many nations in the group. Their teeth were black and crumbling. All of them were starving. They wore suits made of three-inch-wide horizontal stripes of white and blue. They were almost ghostlike in appearance, and they just kept coming. Some would come, kneel in front of the tank, and pray. Others would stand smartly and give a salute. Still others bent over and kissed the front of the tank. I had never seen anything even approaching this. It was clearly the most emotional scene that I had ever witnessed. By now, we surely knew the cause for which we fought.

Then we came across the marks of the barbarous SS soldiers. Lying beside the road were countless wounded and dead concentration camp prisoners. The Germans had fired at them to force them to get in our way, thus delaying our advance. I couldn’t help but cry a little as I saw some of these poor refugees standing silently by the bodies of their buddies who had been wounded or killed. Next, we came upon some of these guards wearing SS uniforms and trying to hide in the village of Posing. Believe me, we gave no mercy. Hoppie Langer and I shot at masses of them. The doughboys on the rear deck of our tank were also popping the SS soldiers off with their rifles. We captured well over a thousand of these SS troopers that day and, because they were dangerous, had guards march them to the rear for imprisonment.

Still the refugees kept coming. They broke into several Nazi food trucks that we had overrun and had themselves a good time eating. They did not know their destination but just kept going. Never in my life have I felt so sorry for one group of people while gaining such disrespect for another.

Orders came to move forward to Cham, our next objective, so we proceeded. About a mile outside of town, our platoon of tanks was sent out to a road on the right flank to protect the main tank column. The remainder of the column went on to the other side of town, where they met firm resistance and became engaged in a short-lived but intense battle. Several hours later, we were called on the radio and ordered to come into Cham and set up a defensive position beside the Regen River in order to protect the rear of the battling troops ahead. We encouraged the doughs to throw thermite (incendiary) grenades into any suspicious-looking building and really clean house.

We saw movement near a culvert off to the left about a mile away, so we started peppering it with machine-gun bullets. We stopped firing for a brief period and a white flag went up. Five Krauts came out with their hands up, followed by five more. Presently, a German staff car came tearing down the road and suddenly stopped when the surrendering Krauts with their hands up came into view. We started firing on the staff car, whereupon it was quickly abandoned by five more Krauts, who joined the other prisoners.

During a lull in the battle, we began investigating the town and discovered a cold-storage warehouse full of eggs. We took seventeen crates, one for the rear deck of each tank. Each crate contained 500 eggs. Having fresh eggs once again was a real treat, but after five days of eating nothing but eggs, we became very, very tired of them.

That night our troops commandeered enough fine homes in Cham, so we had a good dinner, slept in real beds, and heard AFN (European Armed Forces Network) on a radio playing mostly tunes of the forties. In looking through the house where we were staying, I found a package of sugar and some condensed milk and remembered my mother’s family recipe for patience fudge, so I made a batch. All of us enjoyed the candy even if we had no nuts to put in it.

We took an intact airfield in Cham, where a number of good planes were lashed down. Several German planes tried to land after our arrival, so we had no alternative but to shoot them down. Apparently they did not realize that the airfield was in American hands.

We had been engaged in an unusually successful campaign over the past ten days. That night in Cham, because of our recent successes, our company received congratulations from the commanding general of the XII Corps, from the commanding general of the 11th Armored Division, from the commanding officer of Combat Command B, and finally from the 41st Tank Battalion commander. It was not a common occurrence to receive such recognition.

We still had one more day at the point. What would happen next?