29

Rawls and Economics

Daniel Little

Rawls's theory of justice has played a prominent role in a number of academic fields beyond philosophy, and one of these is the field of economics.1 The theory of justice includes many assumptions about how a modern economy works, and it has normative implications for the results of those workings. So it is reasonable to ask whether and in what ways Rawls's thinking was seriously influenced by academic economic theory. A second issue is more substantive. A Theory of Justice is advanced as an ideal theory, abstracted from specific empirical details about modern society. Nonetheless, the basic institutions of a democratic capitalist society are plainly present in Rawls's mind as he develops his theory of justice. So it is worthwhile to consider whether Rawls's theory of justice permits moral assessment of these basic political and economic institutions. Does Rawls's corpus allow us to derive some conclusions about his own considered judgments of the justice and humanity of the institutions of democratic capitalism? This chapter undertakes to examine both aspects of this relationship between moral theory and economics. What role did serious engagement with economic theory play in the formation and development of Rawls's thought? And what concrete assumptions and judgments did Rawls make about liberal capitalism? I will argue that the economic influences on Rawls were fairly narrow – largely the important developments in social choice theory, welfare economics, game theory, decision theory, and microeconomics that emerged in the 1950s. Second, I will argue that his stance toward existing democratic capitalism is more radical than was generally recognized in the two decades following publication of A Theory of Justice.

This chapter has a great deal to do with the question of intellectual influence. Rawls was a “social contract theorist”; to what extent were his theories shaped and framed by his reading of the great contract theorists such as Locke, Rousseau, or Kant? He was also influenced by the history of economic thought; so is it possible to find parallels or echoes of the thought systems of Adam Smith or Karl Marx in Rawls's thinking? And to what extent were there more local influences in the 1940s and 1950s that created fairly specific directions and characteristics in Rawls's thinking? These are interesting questions in application to one particular philosopher. But they also raise more general questions: Where do philosophical theories come from? To what extent is it the case that a given philosopher is working within a “micro-tradition” – a particular and specific field of influence – and to what extent is the thinker “original,” bringing forward new ideas on a topic? And once a fundamental topic has been established for a thinker – for example, “What defines the principles of justice for a market-based democracy?” – to what extent does the theory then develop autonomously according to the arguments and analysis of the philosopher? The question of the economic influences on Rawls's thought sheds some light on these more general questions as well.

Rawls was explicit in addressing the relationship between his own theorizing and the theories of the economists:

It is essential to keep in mind that our topic is the theory of justice and not economics, however elementary. We are only concerned with some moral problems of political economy. For example, I shall ask: what is the proper rate of saving over time, how should the background institutions of taxation and property be arranged, or at what level is the social minimum to be set? In asking these questions my intention is not to explain, much less to add anything to, what economic theory says about the working of these institutions … Certain elementary parts of economic theory are brought in solely to illustrate the content of the principles of justice.

(TJ, 234)

So Rawls is clear in distinguishing the analytics of his own work from that of contemporary economics. At the same time, he is committed to discussing the workings of existing and hypothetical economic arrangements, and this requires a foundational understanding of current thinking in economic theory.

One of the primary goals of Rawls's theory of justice is directly relevant to economic policy. He specifically wanted to work out the implications of the theory of justice for the justice of fundamental economic institutions:

My aim in this chapter is to see how the two principles work out as a conception of political economy, that is, as standards by which to assess economic arrangements and policies, and their background institutions. (Welfare economics is often defined in the same way. I do not use this name because the term “welfare” suggests that the implicit moral conception is utilitarian; the phrase “social choice” is far better although I believe its connotations are still too narrow.) A doctrine of political economy must include an interpretation of the public good which is based on a conception of justice. It is to guide the reflections of the citizen when he considers questions of economic and social policy.

(TJ, 228–229)

Or in other words, philosophy and economics intersect when it comes to analyzing, evaluating, and implementing economic institutions and policies. The subject matter of the theory of justice forces us to pay attention to the actual dynamics and outcomes of existing and hypothetical economic arrangements and the inequalities that they may create. This chapter will attempt to discover the intellectual and theoretical relationships that existed between economic theory and the formation and development of Rawls's thought.

Rawls's Sources in Economics

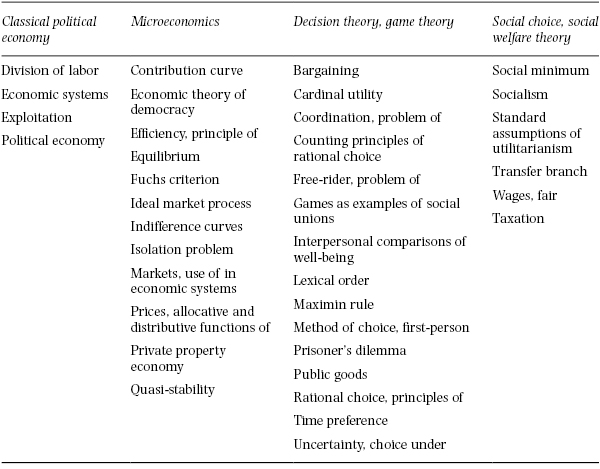

One way of beginning to address these questions is to survey the uses that Rawls made of economic literature throughout his corpus. We can look at Rawls's major papers between 1955 and 1971 as a reasonable sample of the intellectual influences that affected the development of his thought. His first major paper, “Two Concepts of Rules,” appeared in 1955,2 and A Theory of Justice appeared in 1971. All of his major papers during this formative period are included in his Collected Papers, so this is a convenient way of surveying his thought during this portion of his career. What can we learn from these papers when it comes to the influence of the economists on Rawls? Table A in the appendix below provides an inventory of Rawls's references to economists in articles published from 1955 to 1971. Tables B and C provide a similar analysis of A Theory of Justice.

Several things are noteworthy in this inventory. First, Rawls's references are highly contemporary to the 1950s. He appears to have had a high level of acquaintance with what was happening in economics in that decade. But there are virtually no references to earlier figures in the history of economics; Pareto is virtually the only repeat entry in the index from any time prior to 1940 (Pareto principle).

Second, there is a decided focus on several areas of then-contemporary economic theory: welfare economics, social choice theory, and game theory. Von Neumann and Morgenstern are cited numerous times, as are Luce and Raiffa. Kenneth Arrow and John Harsanyi are repeat references as well. (It is interesting to observe that Amartya Sen is cited in later essays, but not prior to 1971.) Keynes is not mentioned in these early articles, and only tangentially in TJ. And there is no mention of general equilibrium theory. Rawls was interested in the areas of economics in the 1950s and 1960s that were relevant to the assessment of social welfare, the formal procedures of democracy, and the theory of rational decision-making in the presence of multiple rational agents. He was evidently not interested in microeconomics, equilibrium theory, or macroeconomics.

Third, none of these citations reflect a significant or substantive discussion of the economist's views. There are virtually no extended passages in these articles from 1955 to 1971 in which Rawls offers a substantive discussion of a point of economic theory. Rather, Rawls tends to illustrate a philosophical point by finding a relevant theoretical claim in one economist or another. This indicates a degree of familiarity with the contemporary literature, but a fairly low level of intellectual engagement with the debates and analytical approaches. In contrast to his treatment of utilitarianism, Kant, or Rousseau, Rawls's treatment of economic theory is brief and nonsubstantive.

Significantly absent from this inventory of references is any mention of the classical political economists. The index of Collected Papers contains no references to Ricardo, Quesnay, or Malthus, and only one reference to Adam Smith (ideal spectator theory; CP, 201). John Stuart Mill is discussed in some detail, but always as a utilitarian philosopher, not as an economist. Marx is mentioned briefly (Critique of the Gotha Programme; CP, 252). The labor theory of value – the central construct of classical political economy – is not mentioned once.

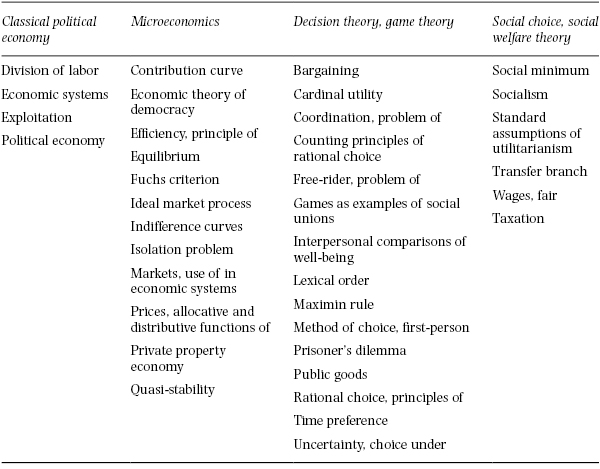

We can also examine the economic content of A Theory of Justice itself for an indication of Rawls's intellectual itinerary. Tables B and C provide lists of economists and topics included in the index of TJ. Table B provides a list of the economists cited in A Theory of Justice ordered by approximate date of their works. The economists cited are disproportionately drawn from 1950–1970. Out of the 36 economists cited, 25 fall in this period. Essentially, these are economists who published their work from the time of Rawls's graduate studies at Princeton through publication of A Theory of Justice. Only five economists prior to 1900 are cited, and six are cited from between 1900 and 1950. (Karl Marx is cited in six places, but none of these citations include his economic writings.) There are a few references to Smith in A Theory of Justice, but they are superficial and incidental. Smith is discussed as a utilitarian, an advocate for the concept of the invisible hand (TJ, 49), and a student of the moral sentiments (TJ, 161, 419) and impartial spectator theory (TJ, 233). There is nothing to confirm a careful or extensive reading of Smith, Ricardo, Malthus, or Marx as economists in A Theory of Justice. This distribution implies fairly clearly that the primary influences on Rawls from economic theory were drawn from mid twentieth-century economics.

A second question that arises is whether we can identify clusters of economic topics in Rawls's discussions and references in TJ. Do the citations included in TJ allow us to do a content analysis of the areas of economics that were of interest to Rawls? Here again the index to TJ is a valuable lens for analyzing Rawls's areas of interest. Table C provides a listing of the topics included in the index to TJ that have clear connection to economics. As the table suggests, these topics fall into four specific areas: a few topics from classical economics; topics associated with the theory of markets and prices; topics associated with decision theory and game theory; and topics associated with social choice theory and social welfare theory. The most frequently cited economists in TJ are Amartya Sen (social choice theory), Kenneth Arrow (social choice theory), F.Y. Edgeworth (utility theory), and Luce and Raiffa (game theory).

In sum, Rawls was reasonably well acquainted with contemporary economics as of the 1950s and plainly found some aspects relevant to his philosophical agenda (Arrow, Harsanyi, von Neumann). Contemporary economists appear to have had significant influence on the formation of Rawls's thought – decision theory, game theory, and social choice theory in particular. But there is little evidence to suggest that Rawls's important philosophical insights on justice were very much shaped by a reading of the history of economics. We will return to Rawls's knowledge of the history of economic thought in the next section.

Rawls and the History of Economics

This review suggests that the most visible economic influences on Rawls fell in the field of modern economics. What about earlier economists such as Adam Smith or Karl Marx? What did Rawls know about the history of classical political economy as he formulated his ideas about social and economic justice, including especially the theories of Smith, Ricardo, Malthus, Marx, or Mill?

It is clear from his lectures on ethics and social and political philosophy (LHMP; LHPP) that Rawls was generally familiar with the basic theoretical positions and debates in classical political economy – the labor theory of value, the invisible hand, the theory of land rent, and the simple theory of a competitive market. And beginning with the marginalist revolution (Jevons, Pareto, and Marshall), he seems to have studied economic theory more carefully. But we do not find any evidence in his corpus of a careful reading of Smith, Ricardo, or Malthus. So what was the source of his knowledge of classical political economy?

One source of exposure to the history of economics occurred during Rawls's first two years of teaching as a lecturer at Princeton. Thomas Pogge indicates in John Rawls: His Life and Theory of Justice that Rawls did significant reading and study of political economy during 1950–1952:

In the fall of 1950, he attended a seminar of the economist William Baumol, which focused mainly on J.R. Hicks's Value and Capital and Paul Samuelson's Foundations of Economic Analysis. These discussions were continued in the following spring in an unofficial study group. Rawls also studied Leon Walras's Elements of Pure Economics and John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern's Theory of Games and Economic Behavior.

(Pogge 2007, 16)

W.J. Baumol's 1950 seminar included study of current work in modern economics, but included as well classics in the history of political economy, including some of Marx's writings. Samuel Freeman describes this encounter and quotes from Rawls in these terms:

Rawls says in his 1990 interview with The Harvard Review of Philosophy that he started collecting notes that later evolved into A Theory of Justice in Fall 1950, after completing his thesis. During this period he studied economics with W.J. Baumol, and read closely Paul Samuelson on general equilibrium theory and welfare economics, J.R. Hicks's Value and Capital, Walras's Elements, Frank Knight's Ethics of Competition, and von Neumann and Morgenstern's seminal work in game theory.

“As a result of all these things somehow – don't ask me how – plus the stuff on moral theory which I wrote my thesis on – it was out of that, in 1950–51, that I got the idea that eventually turned into the original position. The idea was to design a constitution of discussion out of which would come reasonable principles of justice. At that time I had a more complicated procedure than what I finally came up with.”

(Freeman 2007, 13)

We can get some idea of the views of classical political economy that were current in the 1950s and would likely have been conveyed by Baumol by examining Paul Samuelson's writings on this field. In his 1978 article about classical political economy, Samuelson credits Baumol for his careful reading of the manuscript along with George Stigler and Mark Blaug – each an expert on the history of economic thought. Samuelson's goal in this article is to provide a mathematical formulation of the core postulates of classical political economy (Smith, Ricardo, Malthus, Mill, and Marx) and to demonstrate their correspondence to “modern” economics. Samuelson wrote a series of essays on this theme in the 1950s and 1960s and demonstrates a detailed knowledge of the theories offered by the classical political economists. He makes substantial use of Mark Blaug's history of economic thought, as well as works by Michio Morishima and Piero Sraffa.

Another way in which Rawls might have gained a speaking acquaintance with the history of economics is through secondary surveys of the field. Were there standard histories of political economy in Rawls's formative years from 1950 to 1965? Mark Blaug's Economic Theory in Retrospect (1985 [1962]) was well known to Rawls by the time he wrote A Theory of Justice, and it provides extensive and technical discussions of the classical political economists. There are two references to Blaug in A Theory of Justice, and a heavily annotated copy of Economic Theory in Retrospect is contained in Rawls's collection of books in political economy (Schliesser 2011b).3 So there is direct and indirect evidence of Rawls's reading in economics, including acquaintance with this detailed historical analysis of central theories within classical political economy.

One of the great historians of economic thought during those years was Joseph Schumpeter. Schumpeter's Ten Great Economists appeared in 1951. This book focuses largely on postclassical political economy. After a long chapter on Marx, Schumpeter provides short discussions of Walras, Menger, Marshall, Pareto, von Böhm-Bawerk, Taussig, Fisher, Mitchell, and Keynes. More important than Ten Great Economists is Schumpeter's major contribution to the history of economic thought, History of Economic Analysis, which appeared posthumously in 1954. It is possible that Rawls used these books as a sort of intellectual guide to his understanding of the history of economic thought. The only reference to Schumpeter in Rawls's corpus is a single citation of Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (Schumpeter 1947) in A Theory of Justice. This does not preclude the possibility that he read Schumpeter's histories of economics. But is there any basis for supposing that Rawls was in fact acquainted with Schumpeter's work?

Here is a clue worth pursuing. Thomas Pogge notes that Rawls spent a final year of fellowship at Princeton in 1949–1950, and that he spent part of this time in an economics seminar with Jacob Viner, a distinguished Princeton economics professor (Pogge 2007, 15). (The other main area of study during that year was in the history of US political thought with Alpheus Mason.) This serves to establish a tenuous connection to Schumpeter and the history of economic thought. Viner was a significant contributor to economic theory and policy in the 1930s and 1940s at the University of Chicago and Princeton, and he also had a sustained interest in the history of economic thought. In 1954 he wrote one of the first (and most prominent) reviews of Schumpeter's History of Economic Analysis in American Economic Review.

So here is a hypothesis: it seems likely enough that part of the work that Rawls did in 1949–1950 with Viner was concerned with the history of economic thought, and it seems possible as well that he would have learned of Schumpeter's ambitious research on the history of economics from Viner. Schumpeter's book existed only in extensive notes and drafts at the time of his death in 1950 and was edited for publication by his wife, Elizabeth Boody Schumpeter, following his death. Exposure to Schumpeter through Viner would have given Rawls the motivation to study History of Economic Analysis carefully when it appeared in 1954. Rawls was an assistant professor of philosophy at Cornell by that time, and Pogge emphasizes his discipline when it came to reading and reflecting on the materials that he found relevant to his philosophical work. It seems likely, then, that Rawls had engaged in a moderate degree of study of the founders of classical political economy through secondary sources.

Rawls and Decision Theory

I turn now to the influence of “modern” economic theory on Rawls's development. Decision theory and game theory were two areas of economics that Rawls plainly cared about in detail. In fact, one of the most original aspects of Rawls's arguments in A Theory of Justice was his use of the tools of decision theory to help refine and justify his theory of justice. Against the prevailing preference for “metaethics” in the field of philosophical ethics, Rawls made an effort to arrive at substantive, nontautological principles that could be justified as a sort of “moral constitution” for a just society. As is explained more fully in other chapters in this volume, the theory involves two fundamental principles of justice: the liberty principle, guaranteeing maximal equal liberties for all citizens, and the difference principle, requiring that social and economic inequalities should be the least possible, subject to the constraint of maximizing the position of the least well off. (The principle also requires equality of opportunity for all positions.)

Two elements of Rawls's philosophical argument for these principles of justice were particularly striking. The first was his adoption of the antifoundationalist coherence epistemology associated with W.V.O. Quine and Nelson Goodman. Rawls recognized that it is not possible to provide logically decisive arguments for moral positions. Though his theory of justice has much in common with the ideas of Kant and Rousseau, Rawls rejected the Kantian idea that moral theories could be given secure philosophical foundation. It is rather a question of the overall fit between a set of principles and our “considered judgments” about cases and mid-level moral judgments. He refers to the situation of “reflective equilibrium” as the state of affairs that results when a moral reasoner has fully deliberated about his or her considered moral judgments and tentative moral principles, adjusting both until no further changes are required by the requirement of consistency.4

Another and perhaps even more distinctive part of Rawls's approach is his use of the framework of decision theory to support his arguments in favor of the two principles of justice against plausible alternatives (including especially utilitarianism). Essentially the argument goes along these lines. Suppose that representative individuals are brought together in a situation in which they are expected to make a unanimous and irreversible decision about the fundamental principles of justice that will regulate their society; and suppose they are profoundly ignorant about their own particular characteristics. Participants do not know whether they are talented, strong, intelligent, or eloquent; and they do not know what their fundamental goals are (their theories of the good). Rawls refers to this situation of choice as the original position; and he refers to the participants as deliberating behind the veil of ignorance.

Once we connect the question “what is the best theory of justice?” with the question “what principles of justice would rationally self-interested persons choose?” there are various ways we might proceed. Rawls's description of the original position is just one possible starting point out of several. But if we begin with Rawls's assumptions, then it is natural to turn to formal decision theory as a basis for answering the question. How should rational agents reason in these circumstances? How should they decide which of several options will best serve their future interests? One point becomes clear immediately in this context: the choice of a decision rule makes a critical difference for the ultimate choice. If we were to imagine that decision-making under conditions of uncertainty depends upon the “expected utility” rule, then one choice follows (utilitarianism). But Rawls argues that the expected utility rule is not rational in the circumstances of the original position. The stakes are too high for each participant. Therefore he argues that the “maximin” rule would be chosen by rational participants in the circumstances of the original position. The maximin rule requires that we rank options by their worst possible outcome, and we choose that option that comes with the least bad outcome. In other words, we “maximize the minimum.” (The maximin rule was described by von Neumann and Morgenstern in 1944 in their Theory of Games and Economic Behavior.)

Rawls argues that rational individuals in these circumstances would unanimously choose the two principles of justice over utilitarianism. The reason is that the two principles of justice offer a guaranteed high-minimum outcome, no matter what one's initial endowments of talents and resources are. We should be risk-averse about the most life-determining choices that we make; and the two principles represent less risk to the participants in the original position than any other alternative. This assumption does not reflect a general point about human decision-making, it should be noted, but rather a point about the fundamental seriousness of the choices made in the original position. The maximin principle is the most rational decision rule to employ in these life-determining circumstances. This conclusion is taken to be a strong basis of support for the two principles as correct. This is what qualifies Rawls's theory as falling within the social contract tradition; the foundation of justice is the fact of unanimous rational consent (albeit hypothetical consent by abstractly characterized individuals).

Notice that this analysis involves a question of second-order rationality: not “what outcome would the rational agent choose?” but rather “what decision rule would the rational agent follow?” So it is the rationality of the decision rule rather than the rationality of the choice that is at issue.

Another important qualification has to do with defining more carefully what part of the theory of rationality Rawls is using in this argument. It is sometimes thought that Rawls applies game theory to the situation of the original position, and there is a certain logic to this interpretation. Game theory is the theory of strategic rationality; it pertains to that set of situations in which the payoff for one participant depends on the rational choices of other participants. And the original position seems to embody this condition. However, the requirement of unanimity and the complete absence of a context of bargaining makes the situation nonstrategic. So Rawls's use of rational choice theory does not involve game theory or bargaining theory per se, and he is not interested in demonstrating a Nash equilibrium in the original position. Instead, he believes that there is a single best strategy that will be chosen by each individual – the two principles of justice.

One might question whether the two features singled out here – antifoundationalism and decision theory – are consistent. If Rawls's theory of justice depends on an argument within formal decision theory, then why is it not a foundationalist argument? (In fact, Rawls on occasion refers to his argument as reflecting a “kind of moral geometry”; TJ, 105.) What makes Rawls's use of decision theory “antifoundationalist” is the fact that this argument itself is philosophically contestable. Reasonable decision theorists may differ about the rationality of the maximin rule (as John Harsanyi argued against Rawls). So the appeal to decision theory does not obviate the need for a balance of reasons in favor of the approach and the particular way in which it is specified in this situation; and this in turn sounds a great deal like the role of physical theory and methodology within Quine's notion of “The Web of Belief” (Quine and Ullian 1970).

Subjective Preferences and Primary Goods

Throughout the discussion above there has been a back-and-forth between classical political economy and “modern economics.” Classical political economy was premised on the labor theory of value – the idea that there is a concrete, economically meaningful measure of value that guides economic organization. Use value was prior to exchange value. Further, there was the idea that the economic needs that individuals had were also concrete – the consumption goods that permitted life to proceed. So economic activity, according to the classical economists, was about something objective. Neoclassical economy, by contrast, rejected even the idea of utility as a concrete or objective human reality. Instead, modern economics bracketed the reality of needs in favor of an ontology of subjective preference. Economists no longer needed to think about what people needed, but rather simply what they preferred; so the utilities they ascribed to outcomes could be discovered by the quasi-experiments of “revealed preference.” Welfare was then defined as the degree to which the individual can satisfy the range of subjective preferences he or she happens to have.

A major thrust of the twentieth-century critique of neoclassical economics arises at just this point. Development thinkers and economists like Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum have put forward fundamentally different ideas about human well-being. Thinkers like Paul Streeten introduced the idea of basic needs into the discussion of development priorities: they disputed that the goal of economic development in poor countries should be defined in terms of subjective preferences or utilities and argued instead for achieving a decent minimum for whole populations in the satisfaction of basic needs (Streeten et al. 1981). Amartya Sen went a step further, by introducing a more adequate theory of the human person in terms of capabilities and functionings, and argued for a conception of well-being that is defined in terms of the ability of individuals and populations to realize their capabilities (Sen 1999). These are objective criteria of well-being, not simply summations of subjective preference satisfaction.

In light of these comments, it is significant to observe that Rawls defined the situation of deliberation within the original position as one that focuses on primary goods, not subjective utilities. In fact, it might be argued that one of the large contributions Rawls made to contemporary economics is his strong and philosophically convincing case for primary goods. His rationale is that a person's ultimate goals are set by his or her conception of the good, and there is no reason to expect there to be a common agreed-upon standard for the conception of the good. It is logical, however, to observe that there are some goods that every individual requires in order to pursue any conception of the good: access to material resources and liberties. So Rawls's description of the original position stipulates that individuals pay attention to their access to primary goods, and this has more in common with classical political economy than with neoclassical economics.

Rawls and Marx

So far we have considered the possible relationships between Rawls and classical or neoclassical economics. What about his relationship to Karl Marx? Rawls and Marx shared a number of core intellectual concerns. Each was interested in the question of what features a decent society should have; each had theories about the good human life; and each understood that the benefits of modern life depend upon social cooperation. So it is interesting to ask whether Marx's thought had an influence on Rawls. In brief, the answer seems to be largely “no.” In particular, Marx's economic writings and his theory of exploitation seem to have been of no special interest to Rawls during the period leading up to the publication of A Theory of Justice in 1971, judging from the lectures on Marx that Rawls delivered in 1971 through 1973 in his course on the history of political philosophy. My primary evidence for this conclusion is a close reading of the lectures that Rawls offered on Marx in the early 1970s.

Rawls's two primary lecture series have been compiled by former students of his: Samuel Freeman's edition of Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy and Barbara Herman's edition of Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy. The lectures continued into the 1990s, and they certainly evolved significantly during that time. In particular, the lectures on Marx are substantially more extensive by the time of the 1990s than they were in the 1970s. Like many other Harvard graduate students in philosophy in the 1970s, I attended both of Rawls's lecture series on the history of moral philosophy and the history of social and political thought in 1972 and 1973, and I served as a graduate assistant in the latter course. In what follows I have reviewed my notes from the 1973 version of the course to attempt to assess the degree of acquaintance Rawls had with Marx at the time of the publication of A Theory of Justice and to ascertain which aspects of Marx's thought were of the greatest interest to Rawls.

In brief, I find that Rawls knew the “humanist” Marx well and had some affinity with this part of his thought, including particularly the theory of human nature and alienation developed in Marx's early writings. His acquaintance with Marx's economic writings (Capital) was much more limited, however, and this part of Marx's thought seemingly had little appeal to him.

Rawls's teachings about Marx in his courses on ethics and social and political philosophy focused primarily on the early Marx – the “philosophical Marx.” He taught and reflected upon the theory of alienation and species being, and the main texts he focused on were the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, On the Jewish Question, and Contribution to a Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. He gave little serious attention to Capital or Marx's own economic theories. (Rawls used Robert Tucker's Marx-Engels Reader (Marx and Engels 1972) as the primary source of Marx's writings in his course. He also used Tom Bottomore's collection, Karl Marx: Early Writings (Marx 1964).)

There is only one substantive comment about Marx in the lectures on moral philosophy:

A difference between Hegel and Marx in this respect is that Hegel thinks that the citizens of a modern state are objectively free now, and their freedom is guaranteed by its political and social institutions. However, they are subjectively alienated. They tend not to understand that the social world before their eyes is a home … By contrast, Marx thinks that they are both objectively and subjectively alienated. For him, overcoming alienation, both subjective and objective, awaits the communist society of the future after the revolution.

(LHMP, 336)5

Rawls gave more extensive attention to Marx in his lectures on the history of social and political philosophy. (This material occupied roughly two weeks of the 12-week course.) Here are the selections of Marx's writings that Rawls assigned in this course: On the Jewish Question; Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right; selections from The German Ideology; selections from the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts; Capital, vol. I, chs I, sec. 4; VI–VII; IX, sec. 1; X, sec.1; XIII–XIV; and Critique of the Gotha Program.6

The materials assigned from the early Marx in this syllabus provide a fairly complete exposure to Marx's theories of species being, true human emancipation, and alienation. On the Jewish Question and the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts contain rich bodies of argument in which Marx lays out his conception of human activity and freedom. Sections from The German Ideology provide some exposure to the theory of historical materialism. And the Critique of the Gotha Program is a vehicle for discussing Marx's ideas of a socialist society. So this batch of materials offers a reasonably thorough exposure to Marx's thought prior to his political economy and his formulation of an economic theory of capitalism.

By contrast, the imprint of Marx's political economy in this set of lectures is very limited. The readings from Capital break out this way:

- Vol. I, ch. I, sec. 4: The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof

- VI: The Buying and Selling of Labour-Power

- VII, sec. 1: The Labour-Process or the Production of Use-Values

- X, sec.1: The Limits of the Working-Day

- XIII: Co-operation

- XIV: Division of Labour and Manufacturing

This amounts to about 55 pages of reading from Capital, out of the 774 pages of volume I. These readings introduce a few fundamental ideas such as the fundamentals of the labor theory of value, the idea of commodity fetishism, and some of the basics of Marx's sociological description of capitalist society and the economic process within capitalism. But this set of readings provides only a very sketchy introduction to Marx's thinking in Capital. And the most extensive discussion that Rawls provided of any ideas from Capital in his 1973 course – the discussion of Marx's conception of justice in the 1973 lectures – is largely a paraphrase of Allen Wood's analysis in “The Marxian Critique of Justice” (1972). This is true all the way down to the two passages that Rawls mentions from Capital in the course of this lecture; both were previously quoted in Wood's article. So there is nothing original in the 1973 lecture in its interpretation of Marx's thought. Rawls has largely adopted Wood's frame of analysis in treating the question of Marx's conception of justice. This is not surprising, in that Wood's article was itself highly original and rigorous, and opened up a largely new line of interpretation of Marx's theories. But Rawls did not have much to add to the debate in this lecture.

In other words, as of 1973, two years after the publication of A Theory of Justice, Rawls's references to the economic theories and sociological descriptions contained in Capital were very slender indeed. It is justified to conclude that Rawls had not been significantly immersed in a reading of Marx's economic and sociological writings during the formative period of his development of the theory of justice.

This breakdown of topics and readings gives a clue to what Rawls found appealing about Marx. The conception of individuals forging themselves through labor is central; it reflects a line of thought extending from Aristotle to Hegel to Marx, and it seems to be foundational for Rawls himself when he describes his theory of the good. But there are other core ideas in Marx's thought that plainly did not appeal to Rawls. Central is the idea of exploitation. This idea is absolutely core to Marx; but it seems to have played little role in Rawls's theories, by the evidence of his written work and lectures.

Rawls and Capitalism

Let us turn now to the relation between Rawls's theories of justice and the realities of existing economic institutions. How does A Theory of Justice work out as a critique of contemporary economic and political institutions? What can we infer from his writings about how Rawls viewed the society around him? Perhaps surprisingly, Rawls's critique of capitalism now seems deeper than has been commonly recognized. This is a central thrust of quite a bit of important recent work on Rawls's theory of justice. Much of this recent discussion focuses on Rawls's idea of a “property-owning democracy” as an alternative to both laissez-faire and welfare-state capitalism. This more disruptive reading of Rawls is especially important today, 40 years later, given the great degree to which wealth stratification has increased and the political influence of wealth has mushroomed in the United States and Great Britain.

Rawls and Exploitation

We can begin to approach Rawls's view of capitalism by asking what the implications of Rawls's theory of justice are for the concept of exploitation. Is exploitation possible within a society that is just according to the two principles of justice? The concept of exploitation is key to Marx's theory of the capitalist economy. Marx believed, as a matter of objective economic analysis, that capitalism is a system of exploitation in a specific technical sense: the capitalist is enabled to expropriate the unpaid surplus labor of the worker. This perspective on modern economic relations as representing a set of fundamentally unfair economic relations between the powerful and the weak is not one that Rawls found compelling, apparently. And the fundamental ontological framework of Marx's thinking – the idea of capitalism as a system of relations of production through which economic activity transpires – never comes in for detailed description or discussion in Rawls.

Marx's argument that capitalism is inherently exploitative became central in the debate in the 1970s and 1980s over “Marx's theory of justice” (for example, Buchanan 1982 and Wood 1981). If capitalism is exploitative in its most fundamental institutions, then presumably Marx would judge that capitalism is unjust. An extensive debate ensued over the relationship between Marx and justice. These discussions developed quickly into an explosion of interest in Marx by analytic philosophers that took place in the early 1970s. Philosophers such as Allen Wood, George Brenkert, Allen Buchanan, John McMurtry, and Gerald Cohen, political scientists Jon Elster and Adam Przeworski, and economist John Roemer began taking Marx's writings seriously and offering extensive analysis and criticism of his theories. This resurgence began in discussions of “Marx's theory of justice,” but extended quickly into many other areas of Marx's thought – the theory of exploitation, the labor theory of value, the theory of historical materialism, and his theory of capitalism as a distinctive mode of production. Examples of some of this work are included in John Roemer's edited Analytical Marxism: Studies in Marxism and Social Theory (1986). This work was referred to as “rational choice Marxism” or “analytical Marxism,” and it represented an intellectual agenda that took Marx seriously as a thinker but often came to conclusions that jarred the sensibilities of more traditional Marxist thinkers.

It is interesting, then, to consider whether the principles that Rawls describes would in fact permit exploitation in Marx's sense of the term. Marx's concept of exploitation is formulated in the language of labor value and surplus value. Capitalists own the means of production and workers own only their labor power. The capitalist purchases the worker's labor time for a wage that is the equivalent of a certain number of labor hours X. The length of the working day is greater than X. The capitalist subtracts the cost of constant capital (machinery depreciation, space, and raw materials), and is left with a positive sum of value in the form of profit. Marx describes this as extraction of surplus value and as exploitation by the capitalist of the worker.

Do the two principles of justice permit what Marx would call systemic exploitation? It might appear that Rawls's two principles do in fact permit Marxian exploitation. It would seem apparent that the liberty principle creates a basis for the economic arrangements involved in wage labor, in which the labor time of the worker is purchased on the basis of a wage set by a competitive labor market. The worker is at liberty to sell his or her labor power as she chooses.

The critical question is whether the two principles of justice permit private ownership of property in the means of production. There are two plausible approaches we can take on this question, leading to different results. The answer, it would appear, does not depend on the second principle of justice (the difference principle) but rather on the first principle of justice (the liberty principle). This, then, is the central point: does the liberty principle include protection of economic rights, including the right to own the means of production and the right to buy and sell labor power?

It is possible to read the liberty principle as representing a form of Lockean liberalism, with rights of life, liberty, and property to be protected above all else. And in fact, Rawls explicitly includes the right to hold (personal) property as a right protected by the liberty principle. It is only a small step to argue that ownership of property extends to all potential things. On this interpretation, some form of capitalism follows. If the first principle permits private ownership of property, including property in the means of production, then it is not inherently unjust to derive income from ownership of property and to hire workers to make one's property “productive.” Further, if the first principle entails the right to use one's labor as one chooses, then presumably one has the right to sell one's labor time. This is the essence of capitalism. The second principle may moderate the effects of this system; but at best we get welfare capitalism instead of laissez-faire capitalism, and we get exploitation in the technical sense. A surplus is transferred from the workers who create it to the owners of capital. Therefore Rawlsian justice tolerates exploitation, on this interpretation of the liberty principle.

But perhaps the liberty principle does not in fact support these unlimited economic rights after all. This is the view that Samuel Freeman explores in depth in his book Rawls. (2007). In a nutshell, Freeman gives an extensive argument for concluding that Rawls does not include these economic rights under the liberty principle (the right to own and accumulate capital and the right to buy and sell labor time). Here is Freeman's position:

Then again, Rawls resembles Mill in holding that freedom of occupation and choice of careers are protected as a basic freedom of the person, but that neither freedom of the person nor any other basic liberty includes other economic rights prized by classical liberals, such as freedom of trade and economic contract. Rawls says that freedom of the person includes having a right to hold and enjoy personal property. He includes here control over one's living space and a right to enjoy it without interference by the State or others. The reason for this right to personal property is that, without control over personal possessions and quiet enjoyment of one's own living space, many of the basic liberties cannot be enjoyed or exercised. (Imagine the effects on your behavior of the high likelihood of unknowing but constant surveillance.) Moreover, having control over personal property is a condition for pursuing most worthwhile ways of life. But the right to personal property does not include a right to its unlimited accumulation. Similarly, Rawls says the first principle does not protect the capitalist freedom to privately own and control the means of production, or conversely the socialist freedom to equally participate in the control of the means of production [TJ, 54; PL, 338; JF, 114].

(Freeman 2007, 48)

Unlike John Locke, then, John Rawls does not accept the property rights that give rise to capitalism as basic rights of liberty. If these rights are to be created within a just society, they must be governed by the difference principle. Or in more contemporary terms: Rawls and Nozick (Nozick 1974) part ways on liberties even more fundamentally than they do on distributive justice.

If we accept Freeman's argument, then the answer to the question posed above is resolved. The two principles of justice are not a priori committed to the justice of the basic institutions of capitalism; and therefore Rawls's system is not forced to judge that exploitation is just. Or more affirmatively: exploitation is unjust in this interpretation of the liberty principle.

A Property-Owning Democracy

These arguments have very direct implications for one of Rawls's most important discussions of economic institutions, his idea of a property-owning democracy. (The concept of a property-owning democracy seems to originate in writings by James Meade, including his Efficiency, Equality, and the Ownership of Property, 1964.) Rawls offered a general set of principles of justice that were formally neutral across specific institutions. However, he also believed that the institutions of a property-owning democracy are most likely to satisfy the two principles of justice. So what is a property-owning democracy?

Martin O'Neill and Thad Williamson's volume Property-Owning Democracy: Rawls and Beyond (2012) provides an excellent and detailed discussion of the many dimensions of this idea and its relevance to the capitalism we experience now. O'Neill and Williamson argue that the arguments underlying the idea of a property-owning democracy have the potential for resetting practical policy and political debates on more defensible terrain, and they establish the basis for a more radical reading of Rawls.

The core idea is that Rawls believes that his first principle establishing the priority of liberty has significant implications for the extent of wealth inequality that can be tolerated in a just society. The requirement of the equal worth of political and personal liberties implies to Rawls that extreme inequalities of wealth are unjust, because they provide a fundamentally unequal base to different groups of people for the exercise of their political and democratic liberties. As O'Neill and Williamson put it in their introduction, “Capitalist interests and the rich will have vastly more influence over the political process than other citizens, a condition which violates the requirement of equal political liberties” (2012, 3). A welfare capitalist state that succeeds in maintaining a tax system that compensates the worst off in terms of income will satisfy the second principle, the difference principle. But in these recent interpretations of Rawls's thinking about a property-owning democracy, a welfare state cannot satisfy the first principle. (It would appear that Rawls should also have had doubts about the sustainability of a welfare state within the circumstances of extreme inequality of wealth: wealth-holders will have extensive political power and will be able to effectively oppose the tax policies that are necessary for the extensive income redistribution required by a just welfare capitalist state.) Instead, Rawls favors a form of society that he describes as a property-owning democracy, in which strong policies of wealth redistribution guarantee a broad distribution of wealth across society. Here is how Rawls puts it in Justice as Fairness: A Restatement:

Property-owning democracy avoids this, not by the redistribution of income to those with less at the end of each period, so to speak, but rather by ensuring the widespread ownership of assets and human capital (that is, education and trained skills) at the beginning of each period, all this against a background of fair equality of opportunity. The intent is not simply to assist those who lose out through accident or misfortune (although that must be done), but rather to put all citizens in a position to manage their own affairs on a footing of a suitable degree of social and economic equality.

(JF, 139)

Justice as Fairness offers a more explicit discussion of this concept than was offered in A Theory of Justice. In JF he describes five kinds of regimes: “Let us distinguish five kinds of regime viewed as social systems, complete with their political, economic, and social institutions: (a) laissez-faire capitalism; (b) welfare-state capitalism; (c) state socialism with a command economy; (d) property-owning democracy; and finally, (e) liberal (democratic) socialism” (JF, 136–137). There is similar but less developed language in A Theory of Justice (TJ, 228).

Rawls argues that the first three alternatives mentioned here (a–c) fail the test of justice, in that each violates conditions of the two principles of justice in one way or the other. In particular, laissez-faire capitalism fails because it slights the “fair value of the equal political liberties and fair equality of opportunity” (JF, 137). So only a property-owning democracy and liberal socialism are consistent with the two principles of justice (JF, 138). Another way of putting this conclusion is that either regime can be just if it functions as designed, and the choice between them is dictated by pragmatic considerations rather than considerations of fundamental justice.

Here is how Rawls describes the fundamental goal of a property-owning democracy:

In property-owning democracy … the aim is to realize in the basic institutions the idea of society as a fair system of cooperation between citizens regarded as free and equal. To do this, those institutions must, from the outset, put in the hands of citizens generally, and not only of a few, sufficient productive means for them to be fully cooperating members of society on a footing of equality.

(JF, 140)

Rawls is not very explicit about the institutions that constitute a property-owning democracy, but here is a general description:

Both a property-owning democracy and a liberal socialist regime set up a constitutional framework for democratic politics, guarantee the basic liberties with the fair value of the political liberties and fair equality of opportunity, and regulate economic and social inequalities by a principle of mutuality, if not by the difference principle.

(JF, 138)

This last point is important:

For example, background institutions must work to keep property and wealth evenly enough shared over time to preserve the fair value of the political liberties and fair equality of opportunities over generations. They do this by laws regulating bequest and inheritance of property, and other devices such as taxes, to prevent excessive concentrations of private power.

(JF, 51)

And concentration of wealth is one of the deficiencies of a near-cousin of the property-owning democracy, welfare-state capitalism:

One major difference is this: the background institutions of property-owning democracy work to disperse the ownership of wealth and capital, and thus to prevent a small part of society from controlling the economy, and indirectly, political life as well. By contrast, welfare-state capitalism permits a small class to have a near monopoly of the means of production.

(JF, 139; cf. CP, 419)

How would the wide dispersal of wealth be achieved and maintained? Evidently this can only be achieved through taxation, including heavy estate taxes designed to prevent the “large-scale private concentrations of capital from coming to have a dominant role in economic and political life” (JF, 5).

A property-owning democracy, then, is fundamentally different from virtually any version of modern capitalism. It is an economic system in which there is not a fundamental separation of society into wealth-holders and non-wealth-holders. It is one in which virtually every citizen has access to productive wealth. Consequently it is a system in which capitalist exploitation cannot occur, since workers are not “freed” from direct access to productive property. Workers are therefore not compelled to accept exploitative wage relations. It is a system in which political liberties are substantively equal, in that all citizens have roughly comparable abilities to influence and to participate in political debates. So when Rawls suggests that a property-owning democracy (or else democratic socialism) is the only system genuinely compatible with the two principles of justice, he is making a strong claim indeed about the status of existing economic institutions.

Rawls's Later Cultural Critique of Capitalism

During the final preparation of The Law of Peoples, Rawls had extensive interaction with Philippe van Parijs. Van Parijs was particularly interested in the political and legal circumstances surrounding the establishment of the legal structure of the European Union and the obligations states and their citizens would have to each other within the EU. A key question is whether a political body – a state or confederation – needs to encompass a single unified “people” (whether by language, traditions, or culture); or if, on the contrary, such a body can consist of multiple peoples who nonetheless have duties of justice to each other.

What turns on this from a moral point of view is the level of moral concern that members of this kind of union owe each other. Are their obligations limited to the domain of “concern” that gives rise to some obligations of charity? Or are they closely enough interconnected that they are subject to the demands of justice toward each other? If the latter then the difference principle applies to them when inequalities of life circumstances are apparent. If the former then only weaker principles of assistance apply. For van Parijs this question is particularly acute in the case of Belgium, which was even then subject to fissional pressures along linguistic-cultural lines between Flemings and Walloons.

Van Parijs and Rawls exchanged several careful and thoughtful letters on these issues in 1998, and these letters were published in their entirety in Revue de Philosophie Économique in 2003 (Rawls and Parijs 2003). The disagreements between van Parijs and Rawls are very interesting to follow in detail. There is one aspect of the exchange that is particularly intriguing on the subject of Rawls's own assessment of modern capitalism. The passage is worth quoting. Here is an excerpt from Rawls's letter:

One question the Europeans should ask themselves, if I may hazard a suggestion, is how far-reaching they want their union to be. It seems to me that much would be lost if the European union became a federal union like the United States. Here there is a common language of political discourse and a ready willingness to move from one state to another. Isn't there a conflict between a large free and open market comprising all of Europe and the individual nation-states, each with its separate political and social institutions, historical memories, and forms and traditions of social policy. Surely these are great value to the citizens of these countries and give meaning to their life. The large open market including all of Europe is the aim of the large banks and the capitalist business class whose main goal is simply larger profit. The idea of economic growth, onwards and upwards, with no specific end in sight, fits this class perfectly. If they speak about distribution, it is [al]most always in terms of trickle down. The long-term result of this – which we already have in the United States – is a civil society awash in a meaningless consumerism of some kind. I can't believe that that is what you want.

So you see that I am not happy about globalization as the banks and business class are pushing it. I accept Mill's idea of the stationary state as described by him in Bk. IV, Ch. 6 of his Principles of Political Economy (1848). (I am adding a footnote in §15 to say this, in case the reader hadn't noticed it). I am under no illusion that its time will ever come – certainly not soon – but it is possible, and hence it has a place in what I call the idea of realistic utopia.

Several aspects of this excerpt are noteworthy. The first is a tentative skepticism about the goal of creating a European community in a strong sense – a polity in which individuals have strong obligations to all other citizens within the full scope of the expanded boundaries. Rawls seems to equate this goal with the idea of creating a somewhat homogeneous and pervasive European culture, replacing German, French, or Italian national cultures. And he offers the idea that the traditions, affinities, and loyalties associated with national identities are important aspects of an individual's pride and satisfaction with his or her life.

What is surprising about these views is that Rawls seems to overlook the polyglot, polycultural character of the United States and Canada themselves. Both North American countries seem to have created some durable solutions to the problem of “unity with difference.” It is possible to be a committed United States citizen but also a Chicago Polish patriot, a Los Angeles Muslim, or a Mississippi African-American. Each of these is a separate community with its own traditions and values. But each can also embody an overlay of civic culture that makes them all Americans. It certainly doesn't seem impossible to imagine that Spaniards will develop a more complex identity, as both Spaniard and European. So Rawls's apparent concerns about homogenization and loss of collective meaning seem ill founded.

Even more interesting, however, are his several comments about globalization and capitalism. As we observed above in discussion of the idea of a property-owning democracy, Rawls has already expressed the idea that capitalism has a hard time living up to the principles of justice because of the inequalities of wealth that it tends to create. Here he goes a step further and reveals a significant mistrust of the value system created by capitalism. He refers to the world the “bankers and capitalists” want to create – one based on acquisitiveness and the pursuit of profit – and he clearly expresses his opinion that this is incompatible with a truly human life.

The goal of perpetual growth expresses this capitalist worldview, and Rawls reveals his skepticism about this idea as well. He offers the opinion that the pursuit of growth by this class is no more than the pursuit of greater wealth and more meaningless consumption. And he clearly believes this is a dead-end. Instead, he endorses J.S. Mill's idea of a steady-state.

Here Rawls seems to express a cultural critique of capitalism: the idea that the driving values of a market society induce a social psychology of consumerism – a “meaningless consumerism” – that overrides the individual's ability to construct a thoughtful life plan of his or her own.

Finally, Rawls criticizes the neoliberal dogmas about distribution of income that had dominated public discourse in the United States almost since the publication of A Theory of Justice: the theory of trickle-down economics. That theory holds that everyone will gain when businesses make more profits. And, of course, the data on income distribution in the United States since 1980 has flatly refuted that theory.

Conclusion

Several points emerge from this discussion concerning the relationship between economics and Rawls's thinking about justice. First, we can draw some conclusions about what aspects of economics seem to have played a formative role in Rawls's thinking. The economists whose ideas show up in Rawls's arguments are largely those whose work appeared during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The topics that Rawls seems to have followed most closely are only a subset of the field of economics: social choice theory, decision theory, game theory, and social welfare theory. The history of economic thought seems not to have played much of a role in the formation of Rawls's key ideas. Smith, Ricardo, Malthus, and Marx were epochal founding theorists of political economy; but their ideas do not appear to have influenced the course of Rawls's theorizing about justice. He was aware of this tradition of thought, but it does not seem to have exerted substantial intellectual influence on his theories.

Second, Rawls had several specific reasons to be interested in decision theory, game theory, and social choice theory. These fields of economics in the 1950s and 1960s offered a technical apparatus in terms of which to think about justice, democracy, and institutional design, and Rawls plainly expended the effort needed to understand these fields in some detail. Further, he adopted decision theory as a technical resource within his argument from the original position. It is therefore unsurprising that the most common references in Rawls's corpus are to Amartya Sen, Kenneth Arrow, John Harsanyi, Luce and Raiffa, and Morgenstern and von Neumann.

Finally, Rawls's system has definite economic implications, especially when it comes to economic institutions and their consequences. He wants to know how various sets of institutions and rules work to manage the set of opportunities, liberties, and incomes that ordinary citizens possess in a modern society. Furthermore, the two principles of justice, including both the liberty principle and the difference principle, have very specific consequences for how we should judge the justice of various possible institutional arrangements. The ideal of a property-owning democracy provides a basis for a deep critique of the systemic inequalities that contemporary capitalism has created.

The past 40 years have taken us a great distance away from the social ideals represented by Rawls's A Theory of Justice. The acceleration of inequalities of income and wealth in the US economy is flatly unjust by Rawls's standards. The increasing – and now by Supreme Court decision, almost unconstrained – ability of corporations to exert influence within political affairs has severely undermined the fundamental political equality of all citizens. And the extreme forms of inequality of opportunity and outcome that exist in our society – and the widening of these gaps in recent decades – violate the basic principles of justice, requiring the full and fair equality of political lives of all citizens. This suggests that Rawls's theory provides the basis for a very sweeping critique of existing economic and political institutions. In effect, the liberal theorist offers the basis for a radical criticism of the modern order.

Appendix Tables

Table A Economists cited in essays from 1955 to 1971 included in John Rawls, Collected Papers

|

| 1888 | F.Y. Edgeworth, “The Pure Theory of Taxation” | “Justice as Reciprocity” (1971) |

| 1909 | Wilfredo Pareto, Manuel d′économie politique | “Distributive Justice” (1967) |

| 1946 | J.R. Hicks, Value and Capital | “Justice as Fairness” (1958), “Justice as Reciprocity” (1971) |

| 1947 | John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior | “Justice as Fairness” (1958), “Justice as Reciprocity” (1971) |

| 1951 | K.J .Arrow, Social Choice and Individual Values | “Justice as Fairness” (1958), “Legal Obligation and the Duty of Fair Play” (1964), “Justice as Reciprocity” (1971) |

| 1952 | Tibor Scitovsky, Welfare and Competition | “Justice as Fairness” (1958) |

| 1952 | W.J. Baumol, Welfare Economics and the Theory of the State | “The Sense of Justice” (1963) |

| 1952 | Lionel Robbins, The Theory of Economic Policy in English Political Economy | “Two Concepts of Rules” (1955) |

| 1953 | J.C. Harsanyi, “Cardinal Utility,” “Cardinal Welfare” | “Justice as Fairness” (1958), “Distributive Justice: Some Addenda” (1968), “Justice as Reciprocity” (1971) |

| 1955 | Nicholas Kaldor, An Expenditure Tax | “Distributive Justice” (1967) |

| 1955 | R.B. Braithwaite, Theory of Games as a Tool for the Moral Philosopher | “Justice as Reciprocity” (1971) |

| 1957 | I.M.D. Little, A Critique of Welfare Economics | “Justice as Fairness” (1958), “Justice as Reciprocity” (1971) |

| 1957 | R. Duncan Luce and Howard Raiffa, Games and Decisions | “Justice as Fairness” (1958), “The Sense of Justice” (1963), “Distributive Justice” (1967), “Justice as Reciprocity” (1971) |

| 1961 | Jerome Rothenberg, The Measurement of Social Welfare | “Justice as Fairness” (1958) |

| 1963 | Tibor Scitovsky, Welfare and Competition | “Justice as Reciprocity” (1971) |

Table B Economists cited in A Theory of Justice (1971)

|

| 1776 | Smith, Adam | 7 |

| 1863 | Mill, J.S. | Frequent |

| 1871 | Jevons, W.S. | 1 |

| 1874 | Walras, Leon | 1 |

| 1888 | Edgeworth, F.Y., “The Pure Theory of Taxation” | 8 |

| 1909 | Pareto, Wilfredo, Manuel d′économie politique | 2 |

| 1921 | Keynes, J.M. | 2 |

| 1932 | Pigou, A.C. | 3 |

| 1935 | Knight, F.H. | 4 |

| 1939 | Hicks, J.R., Value and Capital | 1 |

| 1949 | Viner, Jacob | 1 |

| 1950 | Nash, J.F. | 1 |

| 1950 | Schumpeter, J.A. | 1 |

| 1951 | Arrow, Kenneth J., Social Choice and Individual Values | 8 |

| 1952 | Baumol, W.J., Welfare Economics and the Theory of the State | 6 |

| 1953 | Myrdal, Gunnar | 1 |

| 1953 | Harsanyi, J.C., “Cardinal Utility,” “Cardinal Welfare” | 3 |

| 1954 | Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas | 1 |

| 1954 | Savage, L.J. | 1 |

| 1955 | Braithwaite, R.B., Theory of Games as a Tool for the Moral Philosopher | 1 |

| 1955 | Kaldor, Nicholas, An Expenditure Tax | 1 |

| 1955 | Simon, H.A. | 2 |

| 1957 | Koopmans, T.C. | 4 |

| 1957 | Little, I.M.D., A Critique of Welfare Economics | 5 |

| 1957 | Luce, R. Duncan and Howard Raiffa, Games and Decisions | 7 |

| 1961 | Sen, A.K. | 16 |

| 1962 | Buchanan, J.M. | 3 |

| 1963 | Marglin, S.A. | 2 |

| 1965 | Olson, Mancur | 1 |

| 1965 | Fellner, William | 3 |

| 1966 | Tobin, James | 1 |

| 1966 | Bergson, Abram | 2 |

| 1968 | Blaug, Mark (2nd edn) | 2 |

| 1969 | Chakravaraty, Sukamoy | 2 |

| 1970 | Vanek, Jaroslav | 1 |

Table C Economics topics cited in index, A Theory of Justice (1971)

Notes

1 Rawls's theory of justice was formulated initially in A Theory of Justice (1971) and was refined and clarified in Justice as Fairness: A Restatement (2001).

2 This was preceded by the publication of “Outline of a Decision Procedure for Ethics” (1951), in CP, which was based largely on his dissertation.

3 Eric Schliesser documents Rawls's use of Mark Blaug in his blog, New APPS: Politics, Philosophy, Science, which has images of several pages including Rawls's annotations and notes (Schliesser 2011b). Schliesser's obituary of Mark Blaug provides more context on Blaug's writings (Schliesser 2011a).

4 See Freeman 2007, Daniels 1996, and Little 1984 for more discussion of the moral epistemology underlying Rawls's theory of justice.

5 Shlomo Avineri's Hegel's Theory of the Modern State, which appeared in shortly after TJ, provides a similar treatment of Hegel view of the modern state and the citizen's freedom (Avineri 1972).

6 These are the assignments listed in the syllabus for Philosophy 171, fall 1973–1974; author's file.

Works by Rawls, with Abbreviations

Collected Papers (CP), ed. Samuel Freeman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Justice as Fairness: A Restatement (JF), ed. Erin Kelly. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

The Law of Peoples, with “The Idea of Public Reason Revisited” (LP). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy (LHMP), ed. Barbara Herman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy (LHPP), ed. Samuel Freeman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

A Theory of Justice (TJ), rev. edn. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Other References

Avineri, Shlomo (1972) Hegel's Theory of the Modern State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,.

Blaug, Mark (1985 [1962]) Economic Theory in Retrospect. 4th edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, Allen E. (1982) Marx and Justice: The Radical Critique of Liberalism, Philosophy and Society. Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Littlefield.

Daniels, Norman (1996) Justice and Justification: Reflective Equilibrium in Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, Samuel (2007) Rawls. London: Routledge.

Little, Daniel (1984) “Reflective Equilibrium and Justification.” Southern Journal of Philosophy 22: 373–387.

Marx, Karl (1964) Karl Marx: Early Writings, ed. Tom Bottomore. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Friedrich (1972) The Marx-Engels Reader, ed. Robert Tucker. New York: Norton.

Meade, J.E. (1964) Efficiency, Equality, and the Ownership of Property. London: Allen & Unwin.

Nozick, Robert (1974) Anarchy, State, and Utopia. New York: Basic Books.

O′Neill, Martin and Williamson, Thad (eds) (2012) Property-Owning Democracy: Rawls and Beyond. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Pogge, Thomas (2007) John Rawls: His Life and Theory of Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quine, W.V. and Ullian, J.S. (1970) The Web of Belief. New York: Random House.

Rawls, John and Van Parijs, Philippe (2003) “Three Letters on The Law of Peoples and the European Union.” Revue de Philosophie Économique 8: 7–20.

Roemer, John (ed.) (1986) Analytical Marxism: Studies in Marxism and Social Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Samuelson, Paul (1978) “The Canonical Classical Model of Political Economy.” Journal of Economic Literature 16: 1415–1434.

Schliesser, Eric (2011a) “Mark Blaug (1927–2011).” In New APPS: Art, Politics, Philosophy, Science, at http://www.newappsblog.com/2011/11/weekly-philo-economics-mark-blaug-1927-2011.html (accessed May 2013).

Schliesser, Eric (2011b) “Rawls, Robbins, and Blaug.” In New APPS: Art, Politics, Philosophy, Science, at http://www.newappsblog.com/2011/11/rawls-robbins-and-blaug.html (accessed May 2013).

Schumpeter, Joseph (1947) Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. 2nd edn. New York: Harper.

Schumpeter, Joseph (1951) Ten Great Economists, from Marx to Keynes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schumpeter, Joseph (1954) History of Economic Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya Kumar (1999) Development as Freedom. New York: Knopf.

Streeten, Paul, Burki, Shahid Javed, ul Haq, Mahbub, Hicks, Norman, and Stewart, Frances (1981) First Things First: Meeting Basic Human Needs in Developing Countries. New York: Oxford University Press.

von Neumann, John and Morgenstern, Oskar (1944) Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wood, Allen (1972) “The Marxian Critique of Justice.” Philosophy and Public Affairs 1: 244–282.

Wood, Allen W. (1981) Karl Marx London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.