Chapter 8

When night fell it was eerie on the canal bank. It was also cold and none too comfortable for there had been no shelter from the thunderstorm that plumped down at ten o’clock and the soldiers were damp and shivery. Mist hung over the water and clung dankly around the trenches scraped across a scrub of suburban wasteland behind the towpath. The Royal Fusiliers had scratched them out hurriedly in the last of the daylight and they were barely two feet deep. This was a point of small importance. The trenches were not meant to be permanent and the Tommies did not for a moment imagine that they were intended to stop there. They expected a skirmish – no more – and then, when the rest of the Army caught up and the powers-that-be gave the word, they would be ready to go, kicking the Germans along the road in front of them.

But, nevertheless, they had to take standard precautions. Foraging parties had gone off in search of bonfire wood and any waste material that would burn, for the canal was lined with empty barges that could all too easily be strung together to serve the enemy as a makeshift bridge. Conventional bridges carried roads and railway tracks across the canal, but the Royal Engineers had been busy all evening, laying explosive charges which, if the worst came to the worst, would blow the bridges up and leave the Germans spectacularly stranded on the opposite bank. But the barges were large, the canal was too shallow to sink them and, with so many men close by, it would be a risky business to use dynamite. The answer had been to set them alight. Now the burnt-out hulks lay askew in the water and the fumes of smouldering wood and pitch still smarted the Tommies’ eyes.

Only this morning – and it seemed a hundred years ago – they had marched into Mons and into the bustle of the Saturday market that filled the Grande Place and spilled over into the streets around. In appointing this rendezvous it had not occurred to the Army to enquire if the streets would be clear. But the Fusiliers were not complaining and nor, apparently, were the citizens of Mons. The Tommies piled arms, balancing rifles together in threes, sat down on the sun-warmed cobblestones round the edge of the square, and prepared to enjoy themselves. Soon their rations were dished out. There was fresh bread – a large loaf to four men – and a tin of food between two. They were mysterious tins, innocent of labels and so battered and rusted that some Tommies loudly speculated on the probability that they came from some long-forgotten store left over from the Crimean War. It was literally pot luck. Some got sliced bacon, others got pilchards or herring and a few were surprised to find that their dinners consisted entirely of apple-dumpling.

It was lucky that appetites had been sharpened by the march for there was more, much more, to come. The market crowds vied with each other to shower the Tommies with eatables that were a distinct improvement on the Army’s fare. There were apples, pears, and greengages by the bushel. There were lumps of tasty sausage, great hunks of cheese, rounds of country bread thick with fresh butter. What the soldiers could not consume on the spot they stowed into their packs as welcome insurance against future hunger pangs.

It was a long halt. Young Bill Holbrook, the Colonel’s servant, made a token appearance at the restaurant where the officers were lunching and then, knowing that if he were missed he would be assumed to be with the Colonel, he set off with his mate for a stroll around the town. They had a most enjoyable time. They were hauled into cafés and treated to beer. They were lavished with fruit, with flowers, with sweets, cigars, cigarettes. A barber rushed from his shop to intercept them and almost frog-marched them inside for free haircuts. They were kidnapped by a teacher at a school for young ladies who entertained them to tea and polite English conversation, with much round-eyed giggling from her pupils. And they returned not a moment too soon, for they were just in time to slip into their places as the Battalion formed up to march through Mons to Nimy and on to its place on the bank of the wide Mons-Condé canal. Somewhere on the other side of it, so they said, were the Germans.

Now they were waiting, watching, listening. But there was nothing to see but the vague bulk of a bridge against the inky black of the night and nothing to be heard but the occasional cry of a night bird, the whistle of a distant train, and now and again the murmur of an officer’s voice as he made his rounds.

Some distance to the rear – and it was just as well, for the sound of his fury would have roused any Germans within a mile of him – another officer, also on his rounds, was giving a subordinate the sharp edge of his tongue in tones that were anything but gentle. This unfortunate Lieutenant had been ordered to set up four outposts to cover the approaches to their makeshift camp in case the enemy surprised them in the hours of darkness. Three were in position when the Major made his rounds. The fourth was not and he wished to know the reason why. The answer came glibly enough from a subaltern whose polite deference was tinged with the merest suggestion that it was plain for all to see.

‘I’m sorry, Sir. I didn’t think it necessary to post one. The enemy would hardly come from that direction. It’s private property, Sir.’

At the end of a nasty five minutes, still smarting from the indignity of having been called a dunderhead and brusquely reminded that he was engaged in war and not in a game of hopscotch, the Lieutenant hurried off to make amends and soon a corporal and four men marched into the grounds of a large villa to keep watch through the night. The Major checked on them himself and warned them to keep a sharp look-out, to show no lights and to make no sound.

But for many miles behind, the night was astir with noise and movement, with the marching of feet, the jingle of harness and the rumble of wheels as the troops and the guns were pushed at a spanking pace towards Mons. The infantry stopped at dusk to bivouac where they could and snatch a few hours’ rest. The gunners kept going, for the guns were badly needed.

Riding just behind his Commanding Officer at the head of the 23rd Artillery Brigade, Jimmy Naylor was half-asleep in the saddle. The Colonel fell back and prodded him in the ribs. ‘Wake up, Trumpeter. We’re just crossing the border into Belgium.’ He was too tired to pay much attention. They had moved so far and so fast that they had moved right off their maps. They still had a considerable distance to travel but when dawn broke, by consulting signposts and asking the way of a friendly farmer who was early up and about, they managed to find their destination and take up their position.

Mist hung over the canal as the sky lightened and a thin drizzle chilled the air. The men on the outpost line stretched their stiff limbs, gulped down mugs of tea, strong and sweet as only the Army could brew it, washed as best they could in the trickle of water that passed for a stream, slapped their arms, stamped their feet and tried to shake off the chill of the night. After a while the drizzle stopped and the sun broke hazily through, the mist turned to wisps and gradually began to clear. Behind the Royal Fusiliers, across a straggle of waste-ground and allotments, the bells of Nimy church were ringing for six o’clock Mass. The Fusiliers looked to their front and waited for what Sunday might bring.

It was perfectly quiet. The canal was still as glass. Just beyond it, where a few cottages clung to the further bank, a wisp of smoke rose from a chimney and the soldiers more than sixty yards away could distinctly hear the familiar domestic sound of a fire being raked and fresh coals rattling into the stove. It sounded disconcertingly like the rattle of musketry. Staring ahead into the mist the look-outs crouching in the shallow outpost trenches could just make out the blur of a fir-plantation on the crest of the long slope rising to the skyline beyond the cottage gardens.

Their first sight of the Germans was hardly more than a shifting of the mist. A cavalry patrol, edging forward with caution, moved out from the smudge of trees on the hill and came riding down the main Nimy road towards the canal. The first that most of the Fusiliers knew of it was a warning shout and then an urgent call of command. At five hundred yards – five rounds rapid – FIRE!

Despite their years of hard professional training few of the Tommies had ever fired a rifle in anger but, like Holbrook, every man in the line was a first-class shot and they fired now as coolly, as steadily, as accurately as if they were firing at targets on the rifle range. It would not have surprised them if an umpire had signalled the hits.

Cpl. W. Holbrook, No. 13599, 4th Bttn., Royal Fusiliers, 4th Brigade, 3rd Division, B.E.F.

Our Colonel McMahon, he was responsible for improving the firepower of the British Army. Wonderful man he was. Before he came to us he was musketry mad! He started the fifteen rounds a minute. When I first joined the Army you fired at a bullseye, that was your target. He ended all that. You fired at moving figures – khaki, doubling – so from about five rounds a minute you went to about fifteen. You had to lie on the box, unloaded, with three rounds in clips of five in the pouches. When the whistle went you’d have to load your rifle and fire, tip the case out, fire, fire, fire, fire … and get it all into the minute.

His one craze was musketry. I was his servant, but you had to fire your course whatever job was on. You had to fire five hundred rounds a year. I got Best Shot in the Battalion, and I was as proud as Punch. I felt sure the Colonel would say something because I got the Battalion Orders from the Orderly Sergeant every night, and I used to take them in to him. This night my name was right at the top as marksman – Best Shot! He saw it all right. He sat at that table and he read it while I watched him. He never said a word! Just signed it and handed it, back and never said a word. I shed tears over that! I couldn’t help it! I knew he’d seen it, I knew he’d thought a lot of it – but he wouldn’t praise me for it.

That wasn’t long before I went with him to France. I went as a marksman.

But, marksman or not, Holbrook was perhaps the only front-line soldier in his company who had not fired his rifle. He was also one of the few men who had not yet seen the Germans. There had been no time to look, for his job as the Colonel’s orderly was to run from B Company Headquarters in the line to Battalion Headquarters in Nimy village, and to run like the wind to keep the Colonel abreast of the news. It was a third of a mile to Battalion Headquarters in a cottage in the main street of Nimy and the steady crackle of musketry had followed Holbrook all the way. By the time he returned to the canal it had stopped and the Germans had retired in some dismay.

At nine o’clock, the first shells began to fall and they went on pounding the canal for an hour. There were some casualties, but there was shelter behind, and they were not many. What hit the Tommies hardest was that not a single British gun replied. When the shellfire slackened they manned their shallow trench and stood indignantly to arms. When it stopped the German infantry started forward.

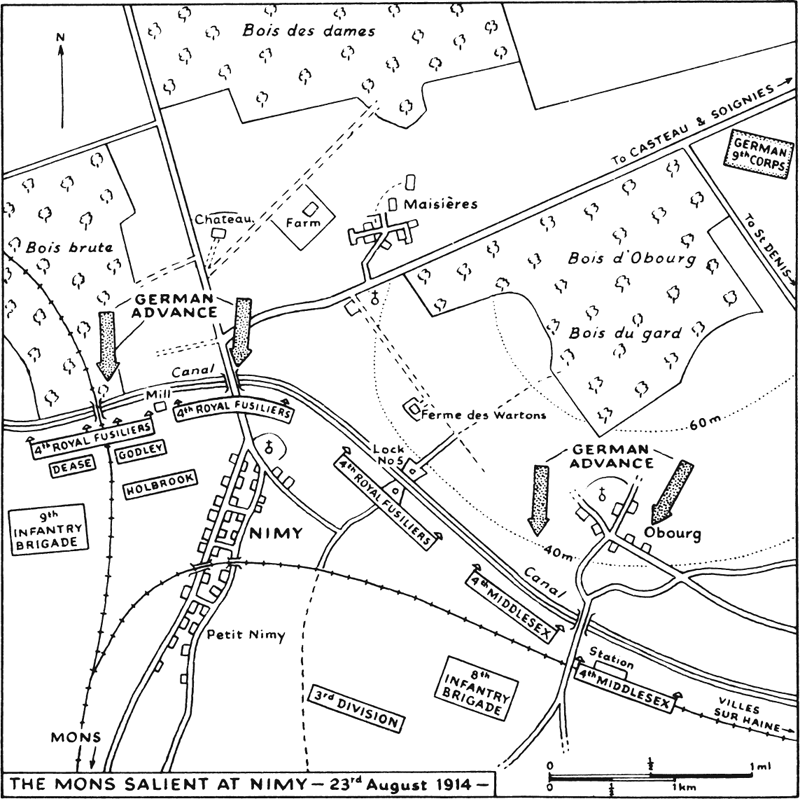

They came in a dense grey mass, swarming down towards the Royal Fusiliers on one bend of the canal and pressing hard against the 4th Middlesex on the other, as if squeezing a flimsy boomerang, to bend it and, by leaning the full weight of their numbers against it, to make it snap. Between them the two battalions were holding the tip of the salient round Mons. It was the weakest point in the line. They knew it – and so did the enemy.

Cpl. W. Holbrook, No. 13599, 4th Bttn., Royal Fusiliers, 9th Brigade, 3rd Division, B.E.F.

Bloody Hell! You couldn’t see the earth for them there were that many. Time after time they gave the order ‘Rapid Fire’. Well, you didn’t wait for the order, really! You’d see a lot of them coming in a mass on the other side of the canal and you just let them have it. They kept retreating, and then coming forward, and then retreating again. Of course, we were losing men and lots of the officers especially when the Germans started this shrapnel shelling and, of course, they had machine-guns – masses of them! But we kept flinging them back. You don’t have time to think much. You don’t even feel nervous – you’ve got other fellows with you, you see. I don’t know how many times we saw them off. They didn’t get anywhere near us with this rapid fire.

The Germans believed, and long after the war they went on believing, that the British had beaten them back with machine-guns. But there were only two, placed high above the canal on the buttresses of the vital Nimy railway bridge, and they made so conspicuous a target that they attracted the full force of the enemy fire. Team after team of gunners was knocked out. Time after time they were replaced, and on the canal bank the riflemen were firing as if every man was competing for his marksman’s badge at Bisley. They were firing at a steady fifteen rounds a minute and they mowed down line after line of Germans.

A little way to the rear, from a pocket of open land to the left of Nimy village, a single section of field guns was valiantly attempting to give what help it could. But it was like spitting against the wind. The shrapnel fell on the Germans like a summer shower, and from a dozen or more of their own guns, well sited in the open country beyond the built-up area, they retorted with a hurricane of shells that all but swept away the fragile British line. By midday it was as clear to the soldiers who manned it as it was to the Germans who besieged it that it was only a matter of time before it would give way.

The trouble was that such British guns as there were were blinded by bricks and mortar – by the dwellings and churches, by the tall-chimneyed factories, by the pitheads, the slag heaps, the timber-yards, that stood between them and their targets. At the tip of the Mons salient where the Germans were concentrating their attack, there was simply no field of fire. And on either side of it where there was, the guns, as yet, had no targets to fire at.

For the moment it seemed hardly to matter. In the mining village of Dour the gunners of the 80th Battery were encamped in a ploughed field surrounded by houses and slag heaps. They woke to the sound of church bells and, falling automatically into the familiar routine of camp duties, they were finding it hard to adjust to the idea that they were on the brink of war. There was the usual cluster of noisy children hanging curiously round the camp. There were civilians going about their business. One good lady who had promised the night before to bring milk and eggs in the morning was as good as her word. She brought butter as well, and bread, newly baked and still warm from the oven. A modest amount of money changed hands and the officers (and the mess orderlies!) enjoyed an excellent breakfast.

There were the usual parades – Gun Inspection to ensure that all was in order and Stables to check on the grooming and welfare of the horses. It was then that they heard the faint but unmistakable sound of firing to the north-east. The church bells were ringing again and the local people, sober in Sunday black, were on their way to church, calling out and waving to the gunners as they passed. They seemed curiously unperturbed, as if they lived in an inviolate world of their own and the soldiers in another. It was as if bullets and shells were strictly the affair of the military and had nothing to do with them. But the Germans were already extending their attack and, by the time Mass was over, the fighting was closer to home.

Lt. R. A. Macleod, 80 Battery, XV Brigade, R.F.A., 5th Division, B.E.F.

About ten o’clock Major Birley and Mirrlees rode off to reconnoitre a battery position to support the infantry on the canal bank on the left flank of the 5th Division. They were the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and they were having a very warm time of it. The Germans were shelling them and they had pushed up a field gun behind a hedge within five hundred yards of a house the KOSBs were holding. They were pounding it to bits. The Major went right through this shelling, looking for a suitable place for the guns. There wasn’t one! The country was absolutely flat, cut up by ditches. No cover at all. The party came back very despondent. Then the Colonel came up himself and he and the Major set off once again on reconnaissance. By this time it was about one o’clock and while they were away we had luncheon. It was our last proper meal for days.

They got back about two o’clock and the Major gave orders for us to move into the village of Dour. We harnessed up and moved off. There was a field in the middle of the village close to Dour church and we left all the vehicles there, dismounted the gunners and marched through the village and turned into a turnip field with a railway running at the bottom. Here we started preparing a battery position along the only possible cover, behind a hedge bordering the railway. It was on a forward slope and, somewhat to our surprise, it was facing north-west.

As the sound of the fighting grew louder and fiercer, as more and more German guns joined in and the shelling intensified, as they laboured to dig emplacements for guns which in their view would face the wrong way, the gunners’ astonishment grew. No shell fired from this position would be of the slightest use to the infantry in front. But although the gunners could not know it, their guns could do nothing to save the day. Their task now was to save the Army. And it would be touch and go.

Behind the battle, another German army was marching steadily towards the open country to the west of Mons. Soon, perhaps in a matter of hours, they would reach it. The guns were being placed to catch the Germans when they appeared and if they failed to stop them, or, at the very least, to make them waver and slow down, the Expeditionary Force would be lost.

Lt. R. A. Macleod, 80 Battery, XV Brigade, R.F.A., 5th Division, B.E.F.

At the top of the slope was a factory with a tall chimney we could use as an observation post. We cut gaps in the hedge and dug the gun-pits so that the top of the hedge would be level with the tops of the gun-shields. And we made gaps in the hedge on the other side of the railway line and filled in the ditches on each side with logs so that the guns would be able to roll forward smoothly when the time came to advance. We had no doubt that we would advance.

To the north of us there was another hedge, five hundred yards away, and beyond it we could see the woods on the high ground north of the canal. This was in the hands of the Germans, so we didn’t dare bring in the guns in daylight or we should have been shelled to blazes as soon as they saw them. We knew the infantry were falling back from the canal bank because we could see them digging in along the hedge five hundred yards in front, and soon others came even further back and started digging in just in front of us along the hedge on the other side of the railway track. All the while the sound of the gunfire and the rifles and machine-guns on our right front to the north of us was getting heavier and heavier – and there wasn’t a blessed thing we could do about it!

It was lucky that young Bill Holbrook was strong and fit. It was lucky that his feet had stood up well to the march, for time and again they had pounded up and down the road as the messages flew between Company HQ in the line and the house in Nimy where Colonel McMahon was anxiously following the fortunes of his hard-pressed battalion. The Colonel was also in touch with Brigade Headquarters and he knew that the 4th Middlesex on the eastern arm of the salient were faring no better. Holbrook did not know the contents of the messages he carried but, as the morning drew on, as the casualties mounted and the line thinned, he had no difficulty in guessing. The last time he sped back to the canal bank, pouring with sweat in the hot afternoon sun, he carried the order to retire.

Captain Byng was nowhere to be seen. He had rushed a platoon up to the bridge, where Lieutenant Dease, twice wounded, was still keeping the single machine-gun firing, as the Germans pressed ever closer. Holbrook handed the message to the only officer he could find. He read it grim-faced and scribbled a reply. Again Holbrook set off. It took him longer this time to reach Battalion HQ and by the time he got there, they were already packing up. The adjutant barely glanced at the message. He nodded to Holbrook. ‘No answer. Cut along now and get back to your company.’ It was easier said than done.

Cpl. W. Holbrook, No. 13599, 4th Bttn., Royal Fusiliers, 9th Brigade, 3rd Division, B.E.F.

Even in the little while I’d been away, the Germans had pulled a gun up on the other side of the road bridge over the canal, and they were firing right down the main street. People were running down the street, civilians, refugees, pushing little handcarts, or carrying what they could – or just running to get away as fast as they could, and they were all mixed up with troops coming back. They were trying to keep in some sort of order, but it was hopeless in all this crush. I couldn’t see anyone of my own unit. Then a machine-gun started up and the bullets started streaming down the road, so I ducked through a gateway into a yard with a brick wall around it. There was another fellow sheltering in there leading a pack-mule loaded with ammunition that he was trying to take up to the front line. Poor chap! After a minute or so he put his head round the gatepost, cautious like, to see what was happening. He got a bullet straight through the head! He just spun round and collapsed at my feet.

That was enough for me. I was off! I went over the back wall. When I got to the house where the HQ was, they’d gone. So I just went back with the crowd. It wasn’t confusion exactly, but you got mixed up, you were all over the place, because you had to get back the best way you could. I don’t know who I was with. They were blokes from all different regiments, but I couldn’t find any of our own chaps anywhere.

The Battalion diary (written up many days later) recorded laconically that the Royal Fusiliers had ‘retired in good order’. That was one way of putting it. It was another thing to do it with nerves that twanged from hours of tension, with ears that rang from the sound of shelling, with muscles that ached from the exertion of the fight and brows that poured with sweat in the blistering sun. There was no question of waiting for a lull, for the enemy was almost upon them. The strip of land they must cross danced under exploding shells, the air zinged with the patter of flying shrapnel and a stream of bullets from hidden machine-guns spat and hissed at their heels. The soldiers had never been taught to retreat. But they were well schooled and disciplined in the art of ‘strategic retirement’ and they knew precisely what to do. It was discipline that got them away. It was discipline that kept them steady as they moved through the inferno to safety. It was discipline, standing fast with the rearguard, that held the Germans off while the rest got away. And it was something more than discipline that kept Private Godley firing the one remaining machine-gun until the last man had gone and the Germans rushed the bridge. Lieutenant Steele was the last man to leave the canal and a handful of the rearguard, sheltering by a wall, watched on tenterhooks as he worked unsteadily towards them, carrying Maurice Dease in his arms and staggering now and again under the dead weight of his unconscious body.*

On their right, the Germans had already managed to cross the canal at Obourg, and the Middlesex, the Gordons, the Royal Irish and the Royal Scots were falling steadily back. They were fighting as they went and they were fighting every yard of the way. The Germans were shaken, but still they came on. By five o’clock they were trickling into the streets of Mons and the British soldiers retiring in front of them were doing their best to get out of it. Now that the salient had cracked and the Germans were concentrating their attack on the long straight stretch of the canal to the west of the town, it was only a matter of time before that cracked too.

But, of course, it had never been intended to hold it and for that excellent reason the troops who had been moving into the area about Mons since early morning had not been sent forward to reinforce the outpost line. They had been deployed further back preparing a new line in a better position near the mining villages of Frameries and Paturages. It was to this position that the troops on the canal bank would retire. It was here that the BEF would stand and fight and, when the time was ripe, launch forward to attack the enemy.

The troops who were still holding on to the straight western edge of the canal bank had not taken a beating but they had taken a hard knock. There were many dead and the makeshift hospitals in the villages behind the line were full of wounded. Their ranks were horribly diminished, but they were still beating off the Germans and waiting for nightfall and the order to quit the line. They had clung to it, as the French had been promised they would, for twenty-four hours. But, even before dusk fell, the weary soldiers heard something that astonished them. It came distantly from the enemy’s lines north of the canal and the Tommies listened in amazement. Just as they might have signalled the end of a day’s manoeuvres the German buglers were sounding the Ceasefire.

Not long after, the soldiers of the Royal West Kents in the line at St Ghislain distinctly heard the Germans singing. They were soldiers of the 12th Brandenburg Grenadiers, they were singing ‘Deutschland über Alles’, and they fully intended the British to hear them. Their audience obliged with catcalls of derision and shouts of ‘Bloody sauce!’ But, all the same, the Tommies quite admired the demonstration. They approved of pluck, and they knew very well that they had given the Kaiser’s army a bloody nose.*

All along the line, even where the enemy had succeeded in breaking through, it was the same story. The Tommies, out-numbered by more than three to one, had not merely thwarted the Germans – they had slaughtered them. In the course of the fighting, a bare dozen battalions at the sharp end of the puny BEF had lost sixteen hundred men, killed, wounded and ‘missing’, but they had delayed the advance of the enemy by one vital day.

The Germans had been hit even harder than the fighting soldiers realised, and they sorely needed a respite. They needed time to bury their dead, to tend their casualties, to bring up reserves and to gather their forces for the next onslaught. Both sides had fought like lions. Both sides were exhausted. Both sides were thankful to stop. Only the guns were fighting on.

Lt. R. A. Macleod, 80 Battery, XV Brigade, R.F.A., 5th Division, B.E.F.

As soon as it was dusk we went back to the Battery and brought it up nearer. Here we had a small supper of hard-boiled eggs and bread. When it was dark we brought the guns on to the position. Behind us a sixty-pounder battery in a wood yard on the crest of the hill was firing over our heads towards the north. We could see the shells bursting in a village which was on fire. In fact so many villages and farms were on fire that the flames lit up the whole horizon. Behind us, the arc lights of the factory and the lights in the town were on all night. It was almost as bright as day. We did some more digging, and then lay down for a couple of hours’ sleep.

During the hours of darkness the troops on the outpost line retired ‘in good order’ into the main position that ran through the squalid villages behind Mons and slipped into line with the troops who had come up in the course of the day.

The distance was short but crossing it was a marathon of endurance, for it started to drizzle and the layer of coaldust that coated the surface of the cobbled roads – bad enough for army boots to grip at the best of times – turned in the wet to greasy slime. The troops hobbled and slipped and swore. They stumbled across endless slippery tramlines, crunched over cinder-heaps, blundered into ditches, tripped over fences in the half-light of the lurid night. Trees and chimney stacks, pitheads and spires stood black against the backdrop of the sky, flickering crimson above the villages burning at their backs.