One

Trading Up to New Luxury: An Overview

America’s middle-market consumers are trading up.

They are willing, even eager, to pay a premium price for remarkable kinds of goods that we call New Luxury—products and services that possess higher levels of quality, taste, and aspiration than other goods in the category but are not so expensive as to be out of reach.

Consider Jake, a thirty-four-year-old construction worker earning about $50,000 a year, whose passion is golf. It took Jake a year to save enough money to buy a complete set of Callaway golf clubs— $3,000 worth of premium titanium-faced drivers, putters, and wedges—although he could have bought a decent set from a conventional producer for under $1,000. During the eight-month golf season in Chicago, Jake works the 6 A.M. shift so he can be on the course by 2 P.M.; he plays eighteen holes nearly every weekday after work and—again, believe it or not—twice on Saturday and twice more on Sunday. He is a three-index golfer, which means he is in the top 1 percent of all recreational golfers in terms of skill.

We played a round of golf with Jake at a public course, during which he described in detail the technical differences and performance benefits of his Great Big Bertha clubs. “But the real reason I bought them,” he told us at last, “is that they make me feel rich. You can run the biggest company in the world and be one of the richest guys in the world, but you can’t buy any clubs better than these.” Then, looking at us with a hint of a smile, Jake said, “When I kick your butt on the course, I feel good. I feel equal. I may make a lot less money than you do, but I think I have a better life.” After the round (during which he did, in fact, kick our butts), Jake carefully placed his clubs in his pickup truck and said, “Thank you, Mr. Callaway, for another fine day.” In 1989, Callaway Golf was not a top-ten golf equipment supplier. Within three years of the introduction of the Big Bertha driver in 1990, Callaway soared to number one in the world.

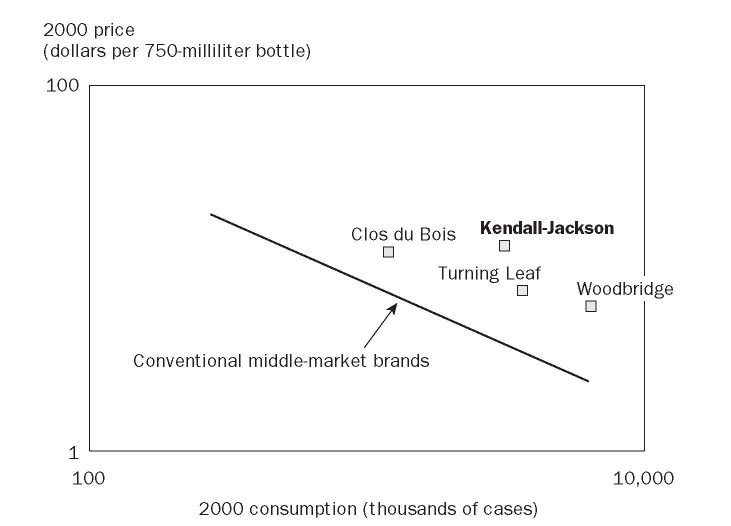

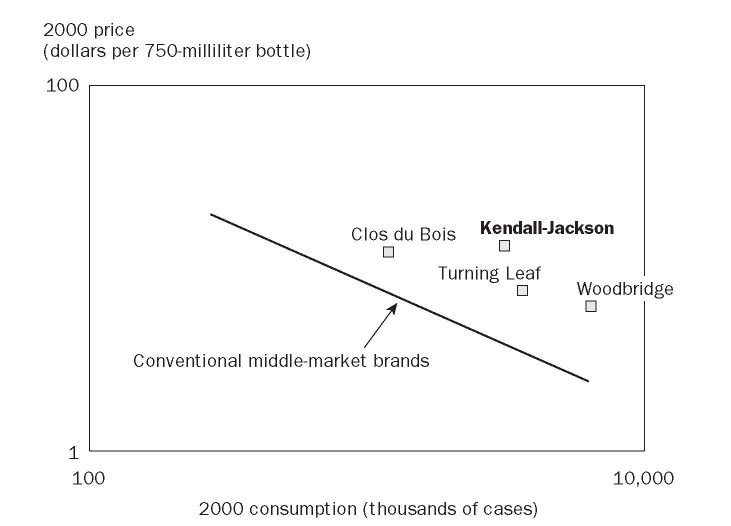

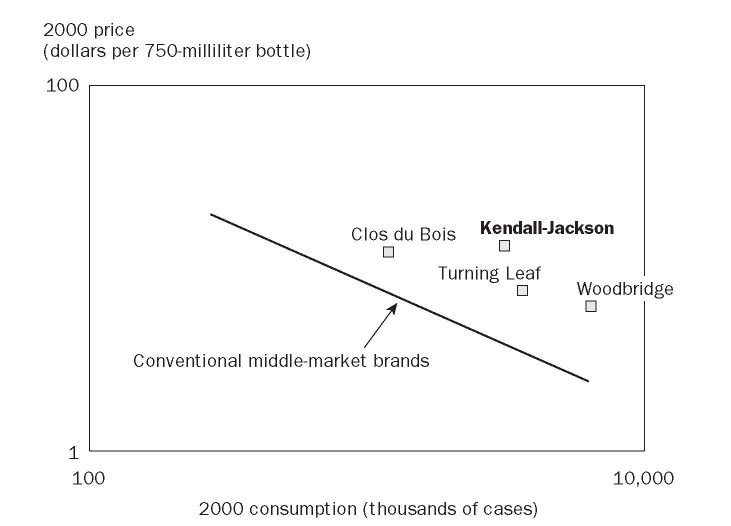

Like Jake, so many middle-market consumers want to trade up, and so many can now afford to, that New Luxury goods have flouted the conventional wisdom that says, “The higher the price, the lower the volume.” They sell at much higher prices than conventional goods and in much higher volumes than traditional luxury goods and, as a result, have soared into previously uncharted territory high above the familiar price-volume demand curve. In category after category of consumer goods and services, New Luxury winners have emerged, traditional leaders have been dethroned, and the entire category has been transformed. The phenomenon forces us to think in new ways about the relationship between consumer needs and consumer goods, and it offers a huge opportunity for business leaders to pursue their own aspirations and realize growth and profit as well. America is trading up, and it’s good for both business and society.

The trading-up phenomenon is happening in scores of categories of goods and services, at prices ranging from just a few dollars to tens of thousands. It involves consumers who earn $50,000 a year and those who earn $200,000. Single moms do it, retired couples do it, working singles, families with kids, and even their pets do it. We have interviewed hundreds of middle-market consumers, observed hundreds more in their homes and workplaces, and conducted a survey of more than 2,300 people earning $50,000 and above. Ninety-six percent of them say they will pay a premium for at least one type of product. With 48 million households in the United States possessing incomes of $50,000 or more, and an average household size of 2.6 people, that’s nearly 125 million Americans with the means and the desire to trade up.

Perhaps the most startling traders up we talked with were a group of consumers ecstatic about a product category that most people would like to forget—a washer-dryer combination from Whirlpool® called Duet®. The pair sells for more than $2,000, compared to about $600 for a conventional washer-dryer combination. Believe it or not, consumers made the following comments about these European-styled front-loading machines: “I love them.” “They are part of my family.” “They are like our little mechanical buddies—they have personality.” We are not making this up, and these people are not paid spokespeople or company employees. These are both women and men, with a range of demographic characteristics, who told us, again and again, that Duet makes them feel happy, like a better person, less stressed, prouder of their children, loved and appreciated, and accomplished. In our fifty combined years of listening to consumers, we have never heard more heartfelt expressions of emotion about a product that even industry insiders think of as mundane and unworthy of much attention. Five years ago, the Whirlpool brand managers, in their wildest dreams, had not imagined there could be that much unit volume for a washer-dryer at that price. Even today, they are astonished by their own success— and are struggling to build enough machines to keep up with consumer demand.

Not all traders up are driven by feelings of happiness and accomplishment; many trade up to manage feelings of stress and difficulty. Frances, a divorced art director earning more than $100,000 a year, had been dating a guy for three years. On the eve of her fiftieth birthday, he told her he was leaving her for a thirty-year-old woman and they were going to start a family. “It sounds like a bad novel,” Frances told us. “I was unhappy. During that time, I bought a lot of jewelry, not only because it was beautiful and I loved it, but because I knew there wasn’t anybody who was going to buy it for me.” She realized what she was doing, and she didn’t jeopardize her financial well-being to do it. “At that particular time,” she said, “I just felt like I needed to give myself a happy pill.” With more women working in the United States, divorce rates on the rise, people marrying later, and more singles choosing to stay that way, there are a lot of consumers—men and women—looking for an emotional lift in the form of a New Luxury purchase.

Trading up spans so many categories and appeals to such a broad range of consumers that it has come to represent a major and growing segment of the economy. In twenty-three categories of consumer products and services worth $2 trillion in annual sales, New Luxury already accounts for 20 percent of the total, or about $400 billion per year—and it’s growing 10 to 15 percent annually. It is about the same size in Europe and growing at a similar rate. And the demand is highly elastic because it can be created in categories that have never had a premium offering before and because even a category that has been transformed by a New Luxury product can be traded up again. We expect New Luxury to reach $2 trillion globally by the end of the decade.

The Characteristics of New Luxury

From our analysis of the most successful New Luxury goods in more than thirty categories, we have identified three major types.

“Accessible superpremium” products are priced at or near the top of their category, and at a considerable premium to conventional offerings. They are still affordable to the middle-market consumer, however, because they are relatively low-ticket items. For example, Belvedere vodka sells for about $28 a bottle, an 88 percent premium over Absolut at $16. Nutro pet food sells at $.71 per pound, a 58 percent premium to Alpo at $.45 per pound. Almost anyone can afford a bottle of Belvedere or a bag of Nutro if those categories are emotionally important to him or her.

“Old Luxury brand extensions” are lower-priced versions of products created by companies whose brands have traditionally been affordable only for the rich—households earning $200,000 and above. Mercedes-Benz, for example, has dramatically changed its product mix in the past ten years, with continual reductions in the price of the entry-level C-class coupe—now about $26,000— providing a steady increase in revenue from this model. Mercedes-Benz has also worked to keep the brand aspirational by extending it upmarket as well. The Maybach sells for over $300,000—more than ten times the price of the entry-level C-class coupe. Such Old Luxury brands have mastered a neat trick: becoming simultaneously more accessible and more aspirational.

“Masstige” goods—short for “mass prestige”—are neither at the top of their category in price nor related to other iterations of the brand. They occupy a sweet spot in the market “between mass and class,” commanding a premium over conventional products, but priced well below superpremium or Old Luxury goods. Bath & Body Works body lotion, for example, sells at $9.00 for an eight-ounce bottle ($1.13 per ounce), a premium of about 275 percent over Vaseline Intensive Care, which sells at $3.29 for 11 ounces, or $.30 an ounce. But it is far from the highest-priced product in the category—Kiehl’s Creme de Corps, one of many superpremium skin creams, retails at $24 for the eight-ounce bottle, a 167 percent premium over the Bath & Body Works product, and there are many other brands that sell for far more.

Despite the wide price range of New Luxury goods and the variety of categories in which they appear, they have particular characteristics that are common across all categories and prices—and they are different from those of superpremium or Old Luxury goods, and also from those of conventional, midprice, middle-market products. Most important, New Luxury goods are always based on emotions, and consumers have a much stronger emotional engagement with them than with other goods. Even relatively low-ticket items, such as premium vodkas, have a well-defined emotional appeal for their consumers. The engagement tends to get more intense and long-lasting with big-ticket items, such as home appliances and automobiles. BMW drivers, for example, are particularly engaged with their cars. Dr. Michael Ganal, a BMW board member, told us that BMW owners wash their cars more frequently than owners of other cars do. They park them on the street and then turn back to gaze lovingly at them as they walk away. By contrast, very expensive Old Luxury goods—such as Chanel handbags and Rolls-Royce cars—are based primarily on status, class, and exclusivity rather than on genuine, personal emotional engagement. And the appeal of traditional middle-market goods is based more on price, functionality, and convenience than on emotional connection: It’s a rare Taurus driver who can be found gazing fondly at his parked car.

Emotional engagement is essential, but not sufficient, to qualify a product as New Luxury; it must connect with the consumer on all three levels of a “ladder of benefits.” First, it must have technical differences in design, technology, or both. Subsumed within this technical level is an assumption of quality—that the product will be free from defects and perform as promised. Second, those technical differences must contribute to superior functional performance. It’s not enough to incorporate “improvements” that don’t actually improve anything but are intended only to make the product look different or appear to be changed. (American carmakers played that game for years.) Finally, the technical and functional benefits must combine—along with other factors, such as brand values and company ethos—to engage the consumer emotionally. Most consumers make one dominant emotional connection with a product, but there are usually others involved as well.

When a New Luxury brand solidly delivers the ladder of benefits, it can catch fire. It will take hold in the minds of consumers, quickly change the rules of its category, grow to market dominance— as Starbucks, Kendall-Jackson, and Victoria’s Secret have—and force a redrawing of the demand curve. As that happens, the category tends to polarize. Consumers shop more selectively. They trade up to the premium New Luxury product if the category is important to them. If it isn’t, they trade down to the low-cost or private-label brand, or even go without. Consumers, especially those at the lower end of the income spectrum, often spend a disproportionate amount of their income in one or two categories of great meaning, a practice called “rocketing.” The combination of trading up and trading down leads to a “disharmony of consumption,” meaning that

Kendall-Jackson wines are off the price-volume demand curve, selling at higher prices and in higher volumes than conventional wines and than competitive premium labels.

a consumer’s buying habits do not always conform to her income level. She may shop at Costco but drive a Mercedes, for example, or buy private-label dishwashing liquid but drink premium Samuel Adams beer.

As consumers buy more selectively, trading up and trading down, they increasingly ignore the conventional, midprice product that fails to deliver the ladder of benefits. Why bother with a product that offers neither a price advantage nor a functional or emotional benefit? Companies that offer such products are in grave danger of “death in the middle”—they will be unable to match the price of low-cost products or the emotional engagement of New Luxury goods. They will lose sales, profitability, market share, and consumer interest. To survive, they must lower prices, revitalize, and reposition their products, or exit the market.

The Forces behind New Luxury

What has caused the rise of New Luxury, and what forces are fueling its growth? We believe that the trading-up phenomenon has come about as the result of a confluence of social forces and business factors. Not since the spread of suburbia and the rise of “convenience” goods in the post-World War II era have we seen this kind of alignment of consumer wants and needs with the capabilities and drives of industry. At that time, consumers’ desire for manufactured goods soared in an arc parallel to that of industry’s ability to produce them. After the emotional and psychic hardships of the war, Americans wanted cars, refrigerators, and household goods in unprecedented quantities. And thanks to newfound capabilities developed and sharpened in the hurry-up production of war materiel, including aircraft, weapons, uniforms, and packaged goods, American industry was ready and eager to meet the demand. Americans wanted to put the pain of war behind them and stretch their new muscles of world dominance. Similarly, today the American consumer is in a state of heightened emotionalism, and, similarly, American businesses have at their command a new set of skills and capabilities. And, like that earlier consumer goods boom, New Luxury is no fad: It is driven by fundamental, long-term forces on both the demand and supply sides, forces that will keep it thriving for years to come.

On the demand side, trading up is being driven by a combination of demographic and cultural shifts that have been building for decades. Most important, American households have more discretionary wealth available to be spent on premium goods than ever before. Home ownership has also contributed to consumers’ increased wealth. Homeowners, on average, have $50,000 worth of equity in their homes, and the entire pool of US home equity is nearly $8 trillion. A less obvious contributor to consumer wealth is the savings that have been passed on to them by large discount retailers. We estimate that in 2003, approximately $100 billion was freed up in this way and became available for New Luxury spending.

Just as important as the increased wealth of Americans is the newly dominant role played by women, both as consumers and as influencers of consumption. Not only are more women working, they are earning higher salaries than ever before; nearly a quarter of married women make more money than their husbands do. Women feel they have the right to spend on themselves.

The traditional American family is becoming less dominant—only 24 percent of American households contain a married couple with kids living at home. Both men and women are getting married much later in life and are having fewer children together. The result is that there are more singles with more money to spend on themselves.

Of the marriages that do take place, half end in divorce; a third of all marriages fail in the first ten years. When couples break up, their consumption patterns change dramatically—the new singles spend more of their money on themselves, both to rebuild their personal brand (how they present themselves to the world) and as a salve for their emotional distress.

The profile of the American consumer is also changing. The middle-market consumer of today is better educated, more sophisticated, better traveled, more adventurous, and more discerning than ever before. Middle-market consumers are also more aware of their emotional states and are more willing to acknowledge their needs, talk about them, and try to respond to them. We all receive countless messages every day—especially from media influences and celebrity endorsers—urging us to reach for our dreams, fulfill our emotional needs, go for the gusto, self-actualize, take care of ourselves, and feel good about who we are. What’s more, these messages are often intertwined with, or linked to, New Luxury goods. The lifestyle gurus endorse products, the celebrities and influencers display them, and the specialty retailers make them available everywhere.

These factors have transformed the profile of the “average” middle-market American consumer from an unassuming and unsophisticated person of modest means and limited influence into a sophisticated and discerning consumer with high aspirations and substantial buying power and clout.

The supply-side forces have been just as important in producing the New Luxury business endeavor. Like the consumers of their goods, New Luxury innovators and entrepreneurs are usually more knowledgeable, more sophisticated and emotionally driven, and less willing to settle for creating conventional goods than established managers in the category are.

Changes in retailing have also contributed to the trading-up phenomenon, by increasing the availability of New Luxury goods in retail outlets across America. The proliferation of malls throughout the country has made it possible for premium specialty retailers, such as Williams-Sonoma and Victoria’s Secret, to expand quickly. Mass merchandisers have also played an important role in the spread of New Luxury goods, stocking more and more premium items on their shelves. Costco, for example, now stocks a larger selection and sells a larger volume of premium wine than any other retailer. Costco stores sell more first-growth wines from the Bordeaux region in France than any other retailer, including wine specialty chains. As retailing has polarized, traditional department stores have found themselves stuck in the middle. They offer similar assortments of goods, display them in similar ways, and provide little emotional engagement or uplift for the shopper. As a result, traditional department stores are in a state of decline.

New Luxury creators have also benefited from the globalization of business and trade. The easing of international trade barriers, the improving capabilities of global supply-chain-services providers, and the reduced costs of international shipping have enabled companies of almost every size to take advantage of foreign labor markets and put together and manage complex global networks for sourcing, manufacturing, assembling, and distributing their goods.

These supply-side factors have made it easier for New Luxury companies to attract investment for the creation of their goods, to develop their products faster and produce them at lower cost, and to increase production volume quickly when consumer demand increases.

The Practices of New Luxury Leaders

The trading-up phenomenon affects, or will soon affect, a wide range of businesspeople in almost every consumer-goods category, including consumables, durables, and services. New Luxury is a business strategy and, as such, must be developed and executed by CEOs and divisional leaders of large companies, as well as entrepreneurs and innovators in smaller companies. New Luxury is product centered, and so it affects product developers as well as supply-chain managers. It also requires a keen understanding of consumer motivations and buying behavior, and so it has significance for market researchers and marketers.

Trading up poses an imminent threat or presents an immediate opportunity, depending on one’s circumstances and point of view. The threat is mostly felt (or should be) by companies offering conventional midprice products to the middle market, because when a New Luxury competitor enters a category, the polarization can happen so fast that it becomes difficult to escape death in the middle. The opportunity is most potent for an entrepreneur or a business with the vision and resources to enter a category that has stagnated and can be traded up. New Luxury creators can move very rapidly from idea to prototype, sometimes in as little as a year. They can create initial product runs, in low volumes, with minimal capital investment. They can often build out their business within five years. When they’re ready to sell, there are eager buyers.

We have learned that New Luxury goods cannot be created, by either entrepreneurs or established companies, with the methods traditionally used to develop products and bring them to market. Across categories and in very different kinds of organizations, New Luxury leaders follow eight practices that we’ll talk about throughout this book:

1. They never underestimate their customers. They believe the consumer has the desire, interest, intelligence, and capability to trade up—even when the entrepreneur has no data to prove his contention nor a business model to follow.

2. They shatter the price-volume demand curve. They don’t settle for incremental improvements or price increases. They prefer the major leap and the big premium. They go for higher prices and higher volume, earning disproportionate profits as a result.

3. They create a ladder of genuine benefits. They don’t try to fool their customers with meaningless innovations, nor do they try to get by on brand image alone. They make technical improvements that produce functional benefits that result in emotional engagement for the consumer. They don’t try to pretend that better cosmetics are true innovations.

4. They escalate innovation, elevate quality, and deliver a flawless experience.The market for New Luxury is rich in opportunity, but it is also very unstable. This is because technical and functional advantages are increasingly short-lived as new competitors enter the market and because of the acceleration of the cascade of innovations from high-end products to lower-priced ones. What is luxurious and different today becomes the standard brand of tomorrow.

5. They extend the price range and positioning of the brand. Many New Luxury brands extend the brand upmarket to create aspirational appeal and down market to make it more accessible and more competitive and to build demand. A traditional competitor’s highest price may be three to four times its lowest; New Luxury players often have a fivefold to tenfold difference between their highest and lowest price points. They are careful, however, to create, define, and maintain a distinct character and meaning for each product at every level, as well as to articulate the brand essence all the products share.

6. They customize their value chains to deliver on the benefit ladder. They put the emphasis on control of the value chain rather than on ownership of it, and they become masters at orchestrating it. Jim Koch, founder of The Boston Beer Company, specified the process for making Samuel Adams Boston Lager (which combined aspects of nineteenth-century brewing with twentieth-century quality-control methods), selected the ingredients, and managed distribution; but he did not choose to grow his own hops or to build extensive production facilities.

7. They use influence marketing and seed their success through brand apostles. In New Luxury goods, a small percentage of category consumers contribute the dominant share of value. New Luxury leaders do not rely solely on traditional consumer-research methods, such as polling and focus groups, to understand who those core customers are; they work harder to define their core audience and spend more time interacting with customers, often one-on-one. Reaching those customers requires a different kind of launch, which involves carefully managed initial sales to specific groups in specific venues, frequent feedback from early purchasers, and word-of-mouth recommendations.

8. They continually attack the category like an outsider. They think like outsiders, act like mavericks, talk like iconoclasts, and strive never to think of themselves as insiders, even after they have become the leaders in their categories.

The Potential of Trading Up

Americans have not finished trading up. There remains vast potential to reshape categories, create new winners, dethrone market leaders, simultaneously destroy and create immense value, and unleash growth and rebirth in mature industries.

Overall, New Luxury is good news for America because it brings benefits to both its creators and its consumers. It is an opportunity and a call to action for businesses because New Luxury goods do what has long been considered impossible—they generate much higher profit margins than conventional middle-market products at much higher unit volumes than superpremium goods. What’s more, they enable entrepreneurs and innovators to participate in a business that is personally meaningful and emotionally engaging and that connects them to consumers whose values they share.

This movement to better goods and services is spreading to new categories and industries. It’s emerging in financial services, where providers have identified the members of newly affluent households as a large potential market, characterized by consumers seeking advice, comfort, and protection. New Luxury is appearing in healthcare, driven by affluent, healthy consumers ages fifty to sixty, who are seeking to take control of their providers and are willing to pay out of their own pocket for care they consider better and more personalized. New Luxury is also causing a transformation in grocery stores. Suppliers of traditional goods are being squeezed by suppliers of gourmet foods, premium prepared dishes, and the proliferation of private-label products.

Trading up, therefore, can benefit us all. For consumers, it offers a new kind of emotional engagement and business influence. For imaginative leaders, it offers a new way to think about growth, profitability, and the art of fulfilling dreams.