Two

The Spenders and Their Needs: Sociodemographics, Emotional Drivers

Who are the New Luxury consumers?

They are a surprisingly diverse group of people—both male and female, all ages, single and married, and in every kind of profession. In conducting interviews with them, what’s most striking is that there is no “typical” New Luxury spender—as defined by demographics, at least—any more than there is a typical American. But they have certain behaviors in common. As our survey shows, almost everyone (96.2 percent) will “pay more” for at least one type of product that is of importance to them, and almost 70 percent identified as many as ten categories in which they will rocket—that is, spend a disproportionate amount of their income, as compared to their spending on other categories. However, only half (48.4 percent) of the consumers we surveyed are prepared to spend “as much as they can” for goods in a specific category, and only half of those will rocket in as many as three categories.

These results confirm our anecdotal findings: New Luxury consumers are defined by their highly selective buying behavior. They carefully and deliberately trade up to premium goods in specific categories while paying less or trading down in many, or most, others. (Some categories, too, are simply of no interest or relevance to them.) The criteria for their selective purchases are both rational— involving technical and functional considerations—and emotional.

Trading up is an important phenomenon because millions of consumers are involved in selective buying in a very wide range of categories. Although trading up involves people of all descriptions, some consumer profiles are more likely to be New Luxury spenders than others: many are single working people in their twenties. Kathy, for example, is twenty-two, lives alone in an apartment in Chicago, and works as a business professional, a job that pays $60,000 a year. “Right now,” she told us, “I do not have anything to pay for except rent and utilities and my telephone. I have a lot of disposable income.” She buys Coach handbags, premium wines, and Panera Bread lunches, and she has “a thing for grocery shopping,” which takes her to specialty and gourmet food shops. But when it comes to shampoo, she “just gets drugstore stuff.” Nor does she trade up on clothing, because “fashion comes and goes, and I can easily cut back in that area.”

Empty nesters are important traders up—married couples, widows, or widowers, with good incomes, whose children no longer live at home. Charles and Judith are in their mid-fifties, with a household income of more than $200,000 and four kids, none of who live with them, from two previous marriages. Like many empty nesters, Charles and Judith spend on travel, their home, and cars. He owns a BMW 3-Series and a Jaguar. She bought a Thermador six-burner range and other premium appliances when they did over the kitchen. But they don’t like to overspend, and they don’t believe in status buying; Charles scoffs at the idea of buying a fancy watch. “We do not make big money decisions without a lot of careful reflection,” Charles told us. “We are willing to spend a lot of money for certain things if we think they have value and we want them and can afford them.”

Divorced women are among the most pronounced traders up. In our survey, divorced women said they would trade up in as many as thirty categories, far more than any other consumer profile. Valerie, fifty-one, has been divorced for twenty-five years. She raised two kids while earning about $60,000 as a coal miner. “Money does not stop me if I really like something,” she says. “I will work overtime to get what I really want. I want what I think is the best for me.” Women who have separated from their husbands, even temporarily, or have broken up with their boyfriends are also prone to disproportionate spending in key categories. Emily, thirty-one, and her husband, Paul, thirty-two, are both lawyers in the public sector, with a household income of over $100,000. They had a fight, and he moved to his own apartment; during that time, she bought a new wardrobe. “I’ve never in my life been a therapeutic shopper,” she told us. But she did it “so that every time he saw me, I was looking good. It was revenge shopping.”

Dual-income couples with no kids, or DINKs, and dual-income couples with kids, DIWKs, are also New Luxury buyers. Because they earn two incomes, they have enough disposable wealth to spend on premium goods, and because they are pressed for time, they feel the need to buy things that make their lives easier and less stressful. Paula, fifty-eight, remembers what it was like to raise three children. “I was working forty hours a week and taking classes. I had to use every minute. It was like I was on a treadmill that never stopped.” Nadyenka, twenty-four, and her husband, Jake, thirty-three, both work, and they have a household income of over $120,000; they have no children. She says, “I am working a lot, so on the weekends I want to treat myself to something special. If I do not balance my hard work with something for myself, it would be too much.”

Rising Incomes and Available Wealth

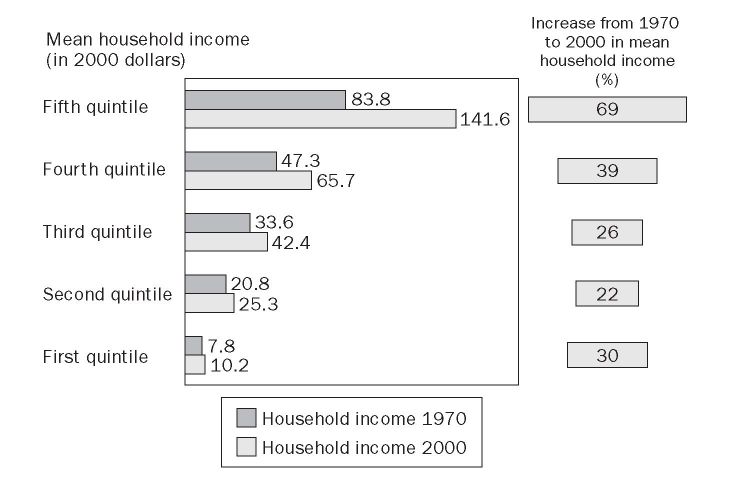

American households have more wealth available to spend on premium goods than ever before. Most of it comes from increased incomes—from 1970 to 2000, real household income rose by more than 50 percent. There are about 112 million households in America today; almost 28 million of them have annual income of $75,000 or more, and 16 million of those take in more than $100,000.

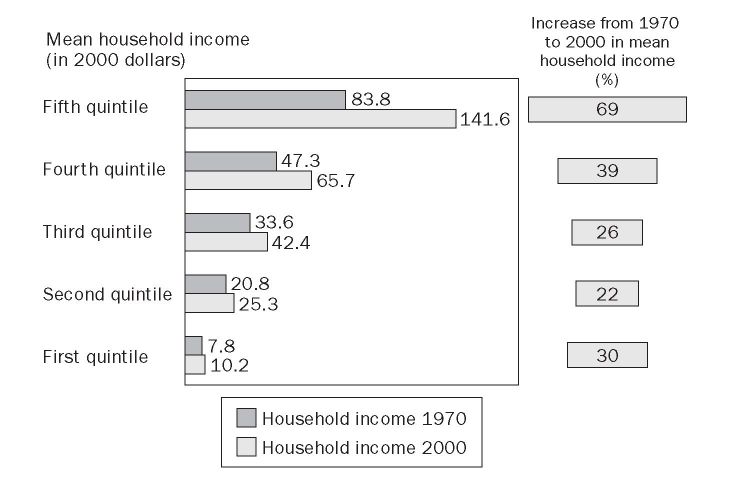

The wealth is becoming more and more concentrated at the top of the income scale. When the population is divided into five equal

The income of the highest-earning households has grown the fastest in the past thirty years, and the gap in household income between top earners and middle earners has widened.

segments, or quintiles, the top quintile—the highest 20 percent, including those earning more than $82,000 per year—accounts for nearly 50 percent of the aggregate income. And income for that segment has risen at a much faster rate than any other, rising nearly 70 percent in real terms from 1970 to 2000. The top two quintiles— the upper 40 percent—account for almost 73 percent of the aggregate. Those upper two quintiles of income constitute the most important market for New Luxury goods.

In addition to rising income, Americans have also financially benefited from a sharp increase in the aggregate value of all their financial holdings, including stock, over the past ten years. Even with the loss of value in the stock market from 2001 to 2003, Americans still have a great deal of accumulated wealth. The top quintile controls some 63 percent of that aggregate net worth; the top two control almost 80 percent of it.

Increased Home Values and Equity

More Americans own homes than ever before—there were some 73 million owned homes in the United States in 2002, up from about 41 million in 1970—thanks to low interest rates, smaller required down payments, a variety of financing options, and government assistance programs. Many homeowners have come to think of their houses as their safest long-term investment, and much New Luxury spending and activity revolves around the home.

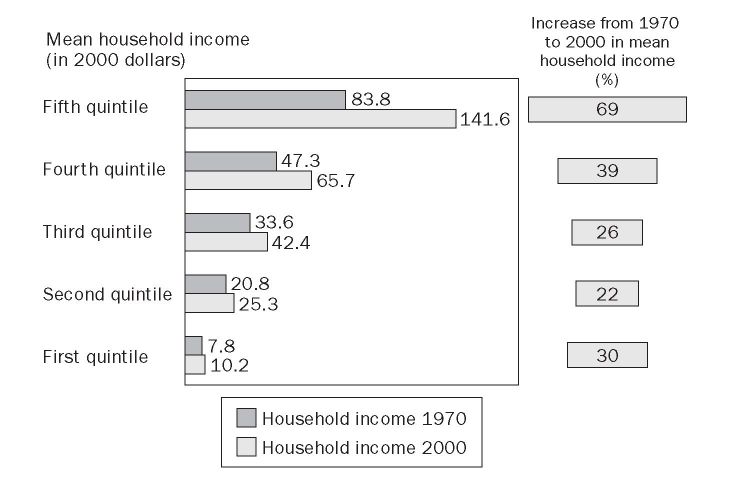

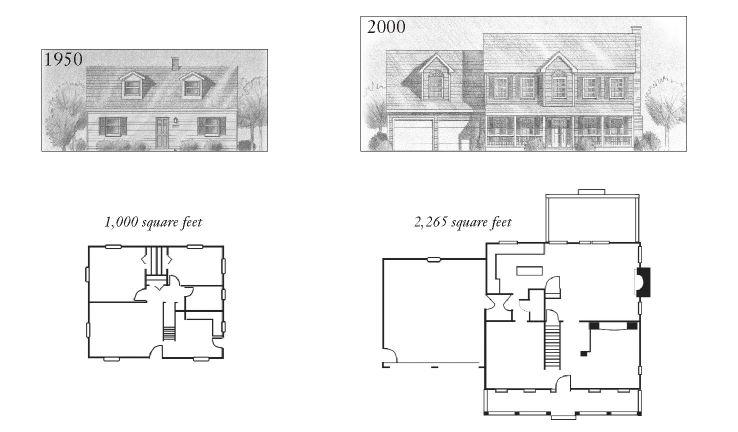

American homes have grown dramatically bigger over the years. In 1950, the typical new home was about 1,000 square feet in area, with two bedrooms, one bathroom, and no garage, air-conditioning, or fireplace. In 2000, the average new home was about 2,265 square feet, with 3 bedrooms, 2.5 bathrooms, a two-car garage, central air-conditioning, and at least one fireplace.

Homes have gotten bigger, but they sit on smaller lots of land. The average lot size in 1985 was 17,610 square feet (about 0.4 acre); in 2000 it had shrunk to 12,910 square feet (about 0.28 acre). This means that a greater percentage of the homeowner’s total domain is inside the house, making interior accoutrements all the more important.

Sales of new and existing homes have been on the rise, as have their values—and the hottest action is in high-value homes, those selling for over $250,000. The result is that we have a giant pool of home equity, some $8 trillion. The average homeowner has unrealized gains in the value of his house of about $50,000. Homeowners have not been reluctant to tap into that wealth; nearly half of them have taken a home equity loan, line of credit, or second mortgage. Twenty-two percent of those who have refinanced took out some cash as part of the transaction. Home equity has provided the fuel for much New Luxury spending, much of it for the home.

Because houses are bigger and more valuable than ever, it is no wonder that a lot of money taken out gets poured right back into them in the form of improvements and new fixtures and appliances. Besides, the home is the most emotionally rich possession to most

New American homes have grown dramatically bigger, doubling in size since 1950, and they have more amenities than ever before.

consumers, and money spent there is rarely considered to be wasted. In 2001, Americans spent some $160 billion on goods and services for their homes, up from $67 billion in 1970. (Home Depot grew from $1.6 billion in sales in 1985 to $54 billion in sales in 2001— equal to more than a third of our national spending on home improvement.)

Much of the money ends up in the kitchen and bathroom. Sixty-three percent of all home-improvement projects undertaken in 2000 involved kitchen improvements such as granite countertops, flooring, lighting fixtures, commercial-grade appliances, dual dishwashers, and undercabinet refrigerators. Bathrooms run a close second: 61 percent of all projects involved upgrades to the family bath, including multiple-head or steam showers, vanities, and in-floor heating systems. These rooms, along with the bedroom, are the most emotionally meaningful areas of a home. The kitchen is the central place for connection among family members; the bathroom is an important place for individual rejuvenation and restoration.

There has also been a rise in second-home ownership. There were 1.7 million second homes in 1980; today there are over 4 million. Second homes often have at least as much emotional meaning as primary residences. As people change jobs and locations, and as families trade up to bigger and better primary homes when income and interest rates allow, they may maintain a longer and deeper relationship with the vacation house. It makes sense to buy special things for such a special place. That’s why even smaller second homes by the lake or in the mountains boast granite countertops and marble baths, Pottery Barn furniture, cotton bathrobes from Restoration Hardware for the guests, and dinnerware from Crate and Barrel. The second home is a place for regeneration, and every night spent there is precious; the better the goods, the better the memories.

Reduced Cost of Living and More Discretionary Income

Another contributor to consumers’ wealth is the savings that have been passed on to them by large discount retailers. Over the years, mass retailers such as Wal-Mart, Costco, Home Depot, Lowe’s, Kohl’s, Circuit City, and others have reduced costs and compressed margins so that consumers have been able to enjoy “everyday low prices” on a wide variety of goods and, as a result, lower their cost of living. We estimate that in 2001, at least $100 billion was freed up in this way and became available for New Luxury spending, and the trend will likely continue in years to come.

The rise in real income, combined with the increase in aggregate value of assets including the home and the reduction in the cost of living, have led to a rise in discretionary income—money left over after the necessities have been purchased—for everyone. There is no precise definition of discretionary income, however, and no standard way to measure it, because there is no absolute dividing line between what is “necessary” and what is “not necessary,” or “luxury.” Most Americans, even the lowest-income earners, can afford the necessities of physical survival—food, clothing, and shelter—and have money available for other needs and wants. We estimate that, in the last thirty years, at least $3 trillion has been created and become available for spending.

The relative nature of needs and wants and the relative elasticity of discretionary income are at the very heart of the trading-up phenomenon, because they mean that every consumer has a different idea of what is necessary for him to survive in his own world and what he is willing to spend to do so. As one consumer put it, “Necessity is one of those relative terms that depends on who you are or where you are in your life. When things become important to you, they become necessities.”

Women as New Luxury Earners and Spenders

Women are the dominant New Luxury consumers, but they are very different from the “housewife-consumers” of the 1950s.

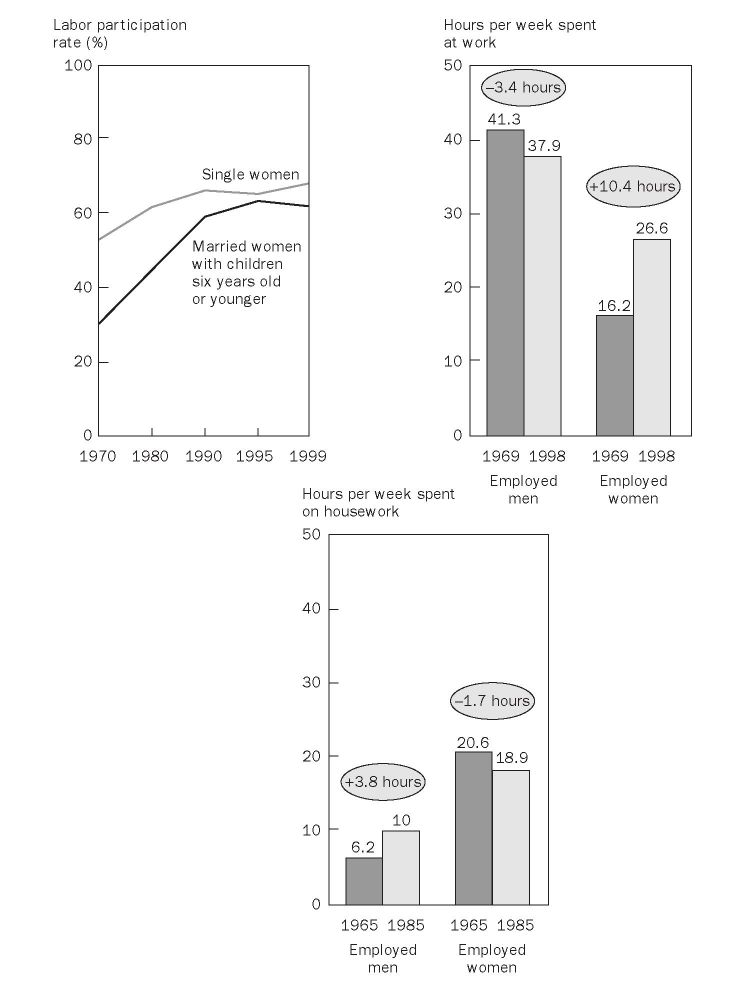

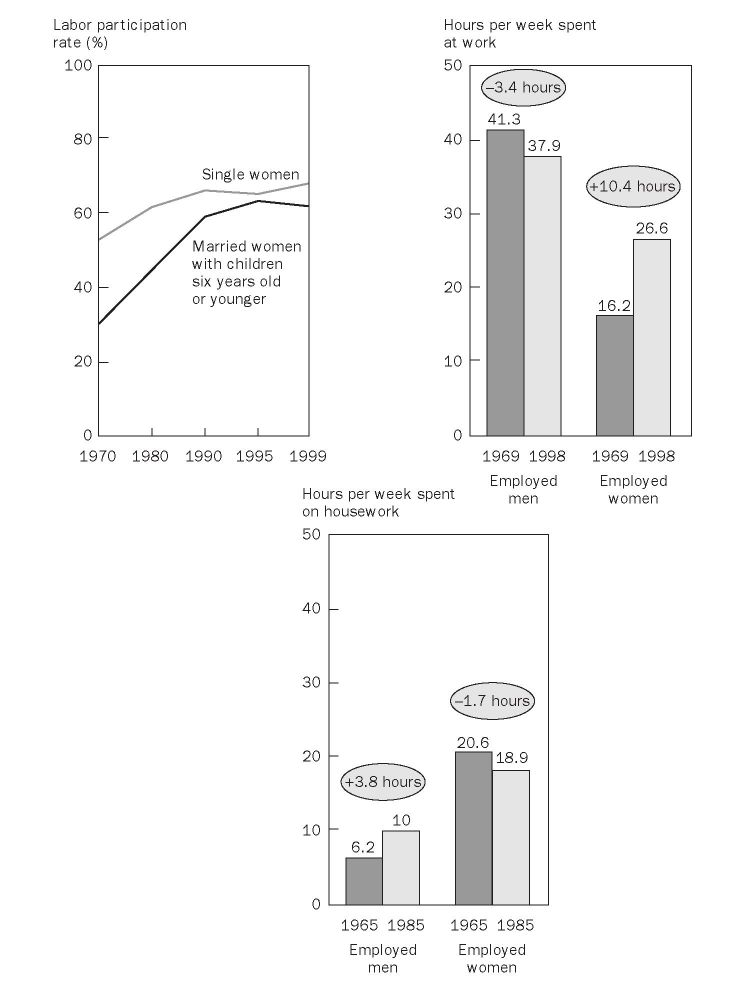

Today, most American women participate in the workforce. Sixty percent of all women aged sixteen to sixty-four work, either full-time or part-time; 76 percent of women aged twenty-five to fifty-four—the peak earning years—work. Not only are more women working, they are earning higher salaries than ever before. Real median income (in 2001 dollars) for women employed full-time rose from $21,477 in 1970 to $30,240 in 2001, an increase of 41 percent.

Women are also working more hours than they used to. Twenty percent of working women put in forty hours a week or more, up from 13 percent in 1976. Twice as many women work forty-nine hours or more per week than did in 1970. And 7 percent of working women are on the job between forty-nine and fifty-nine hours a week. Although nearly a quarter of working women are part-time employees, the average number of hours they worked per week has also increased—from 16.2 in 1969 to 26.6 in 1998. This increase in working hours is significant because it adds to the strain of working women with families—there are “never enough hours in the day” to get everything done.

Many more women are single. Women are less likely to get married, and those who do marry do so later in their lives. The percentage of unmarried women aged twenty-five to twenty-nine has more than tripled in just the last thirty years, from just 11 percent in 1970 to 39 percent in 2000. That cohort of young, single, working women is highly influential in the New Luxury market, as consumers and as tastemakers.

The result of these societal shifts is that large numbers of single working women are earning lots of money—in excess of $374 billion each year. They have few financial obligations apart from their own living expenses and, in some cases, student loans. They have no families to buy goods for, and they are generally too young to be concerned about saving for retirement or for the education of their as-yet-unborn children. The ones who cohabit—and the number of cohabiting couples has grown from 439,000 in 1960 to 4,736,000 in 2000—are in most cases living with another wage earner. So they feel free to spend and to consume as they wish, and they are prime candidates for certain categories of New Luxury goods, including fashion, food and beverages, cars, furniture, pet food, and travel.

(It’s interesting to note that the influence of young single women on the economy is not a phenomenon unique to our society. In Japan, there are about 5 million young, single, working women who live at home with their parents. They spend up to 10 percent of their annual salary on fashion items, and they are the largest spending segment of Japanese society. As a result, they are powerful tastemakers: they have helped make Louis Vuitton the most successful luxury brand in Japan.)

There is a final reason that women are so important in the trading up phenomenon. Most observers agree that women have always had a particular ability to judge the value of goods, especially the goods that make up the bulk of the retail market, and a keen understanding of the complex emotional meanings and social messages contained in them. In our interviews, we found that female consumers are highly attuned to the subtle messages contained in brands, colors, and the minutest details of design, manufacture, and packaging— and from a very young age.

Their tremendous sensitivity to and understanding of products, coupled with their greater purchasing power and influence, means that women are the quintessential New Luxury consumers. They have the means, the motives, and the opportunities to purchase goods—especially goods that meet important emotional needs.

A Changing Family Structure

Just as there is no typical New Luxury consumer, there is no typical American family. The traditional image of the family composed of mom, dad, and kids all living at home together describes just 24 percent of American households. Even those households look different than you might assume, because the parents are older, there are fewer kids, and in most of them, both parents work.

Men as well as women are getting married much later in life than in the past. In 1970, the median age of people at first marriage was 20.8 years; by 2000, that figure had risen to 25.1 years. Partly as a result of later marriages, women are having their first child later in life as well. Over the last three decades, the median age of a mother at her first birth has risen from 22.5 to 26.5 years; during the same period, the percentage of women having their first child after age 30 rose from 18 percent to 38 percent. Delayed childbirth has caused an increase in the number of DINK households, and these couples are major contributors to the New Luxury market because they have money to spend and few obligations beyond their own needs and wants.

Not only are women having children later in life, they are also having fewer kids in total. From 1970 to 2000, the birthrate dropped from 87.9 for every 1,000 women of childbearing age to 67.5 per 1,000. The reduction in the birthrate has contributed to a fall in the average household size—from a median of 3.11 people per household in 1970 to 2.60 in 2000—as well as a decline in the number of households with children under the age of eighteen. The result is that real per capita income has risen substantially. The share of income for each household member was $12,400 in 1970 and rose to almost $22,000 in 2000, a rise of more than 75 percent. That means there is more money to go around in the average family to fuel important purchases.

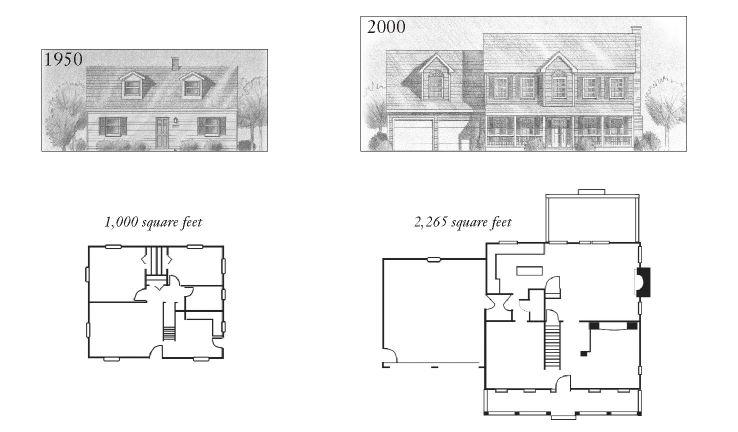

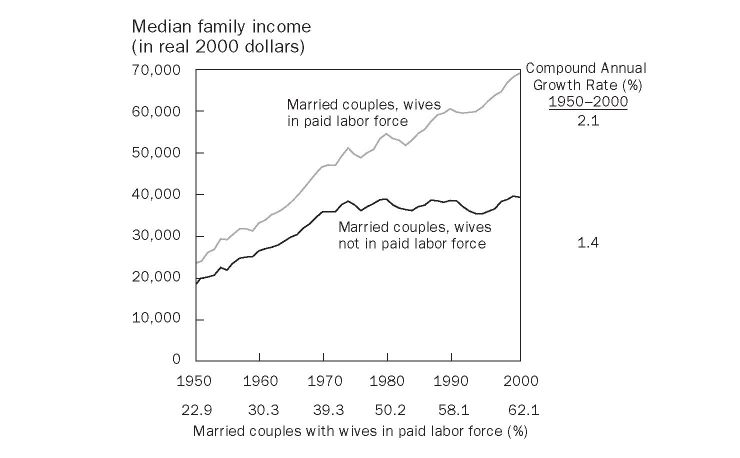

The growth in incomes of married couples has largely been driven by the participation of wives in the labor force.

Even when women do have their children, they are likely to keep working. In 1960, working women who were married and had kids six years old or younger were a minority, constituting just over 18 percent of the workforce. In 2000, that percentage had risen 44 points to almost 63 percent. The percentage of married working women with kids aged six to seventeen has also jumped—from 39 percent in 1960 to 77 percent in 2000.

And yet working women continue to shoulder most of the child-care responsibilities and do the vast majority of housework, including laundry, cooking, shopping for groceries, and caring for sick family members. Married working women with kids are, in effect, working two shifts. They feel overburdened and freely admit that they need help in managing their duties and that they need moments of relief and restoration whenever they can grab them. Because they have the money to spend, they will pay a premium for New Luxury goods that can lighten their workload and soothe their souls. As Nicole, a twenty-eight-year-old lawyer, comments, “Women are more willing to spend on themselves today. We think that our mothers didn’t get

American women are working more than ever before, and they are workinglonger hours and still doing most of the housework; they are emotionallystressed and hard-pressed for time to get everything done.

to spend on themselves because they weren’t earners, but we can because we do earn. The financial independence of women leads to the ‘I can buy it if I want’ attitude.”

A Longer Dating Period and High Rates of Divorce

Because people are getting married later in their lives, young people spend more time and money on dating, branding themselves, and experiencing the world. Many of them choose not to marry at all, and as their incomes rise, they have increasingly large amounts of discretionary cash to spend on goods that please them. Many of those who do marry enter their first marriage with significant amounts of discretionary income and savings, which they can apply to purchases for the home and family.

Although people are entering marriage later (and presumably with more careful consideration), divorce rates remain high. From 1973 to 1995, the probability of a marriage’s ending in divorce during the first ten years rose from 20 percent to 33 percent. More than 50 percent of all first marriages end in divorce, as do 58 percent of second marriages.

Though women tend to have less wealth after a divorce than when they were married, our survey shows that divorced women are pronounced rocketers. Divorced people, both male and female, dine out more often, buy cars and clothes, renovate or decorate their homes, take adventure vacations, and purchase apparel and accessories as a way to smooth the transition to a new style of life. They are an important market, with a distinct set of values and interests and a special relationship with brands.

Education, Sophistication, and Worldliness

The trading-up phenomenon would not have emerged as dramatically as it has—even with increased wealth and the influence of women—if the American consumer had not also become better educated, more worldly, and more sophisticated.

More Americans are college educated than ever before. Even so, the percentage is lower than one might think—just over 50 percent of the population aged twenty-five and older has completed at least some college. Traditionally, more men than women earned college degrees, but the ratio began to change in the 1990s. By 2000, 13 percent of women aged twenty to twenty-four had earned degrees, while only 8.6 percent of men aged twenty to twenty-four had. However, for both men and women, a higher level of education generally equates to a higher level of income. So 58.1 percent of people in the top quintile have earned a college degree, in comparison to the 27 percent average for all Americans.

The impact of a college degree is not only on consumers’ ability to earn money; it also tends to increase their appreciation of learning in general and throughout the course of their lives. Consumers talk about learning as a key attraction of certain types of goods; they like to know the story of the brand and understand something about the category.

New Luxury consumers also like to learn about specific products and the companies that make them. That’s why so many New Luxury brands have a narrative associated with them. Every American Girl doll is created with a complete life story from a specific era of history, told in beautifully produced full-color books. American Flatbread frozen pizza tells how its founder got the idea for his pizza and puts the story right on the back of the box.

Americans have also become big travelers. As airfare prices have fallen, the number of travelers to Europe has risen sharply. In 1970, 3 million Americans visited Europe; 11 million visited in 2000. Travel to Asia also has become increasingly popular. The number of travelers there increased 93 percent from 1990 to 2000. Japan is the most popular Asian destination, but the number of travelers to China is the fastest growing.

“Travel is broadening,” as the cliché goes, and it has certainly contributed to Americans’ awareness of European styles and goods in a number of categories, including cars, appliances, leather goods, bath and body care, fashion and accessories, food, water, wine, and coffee. This has led to US products that pick up on European styles without copying them exactly. It has also led to an increase in imports of European goods, including low-end products such as bottled waters and high-ticket items such as luggage and automobiles.

In recent years, American travelers have ceased to be content with traditional European sightseeing. Travel is increasingly seen as an educational experience rather than as just a vacation. People want unusual and special adventures and are willing to pay for them. Food lovers take a cooking tour in Paris. Adventurers visit with Samburu villagers in Kenya. For many overworked and stressed Americans, travel provides experience of cultures that seem to have a slower pace of life, greater emphasis on enjoyment, more time spent with friends and family, and greater personal fulfillment.

These travelers return with an appreciation for new tastes and looks, exotic goods and ideas, and they want to incorporate them into their lives at home. The appeal of many New Luxury goods is that they have an element of the exotic to them, or they remind the consumer of some experience or emotion she experienced during her travels. Betsy, a twenty-two-year-old professional, shops in specialty grocery stores because “they give you a better feeling, as if you’re buying your food from a place that values customers like you. It’s more like an Italian market.”

Cultural Permission to Spend

Even the increase in wealth, the influence of women, and greater sophistication might not have produced the emotionally driven New Luxury consumer, because one very powerful inhibiting factor still stood in the way: guilt. Americans have always valued hard work and looked askance at overconsumption. But in the 1960s there began a barrage of messages that said it was important for Americans to reach for their dreams, fulfill their emotional needs, be all they can be, self-actualize, and, not only do all that, but also take care of themselves, look after number one, reward themselves, and build their self-esteem.

Products and services were always intertwined with these messages, so it gradually became clear to consumers that they were being given permission to consume a little more aggressively than they had in the past—if consumption was in the service of a higher good, such as self-improvement or building relationships. Not only did the influencers give American consumers permission to “go for it,” they actively encouraged them to do so. And, in a final act of helpfulness, the influencers presented their audiences with lifestyles to emulate and endorsed products for them to buy.

Oprah Winfrey is a world-class encourager, especially, of course, of women. Her mission is an ambitious one: “To use television to transform people’s lives, to make viewers see themselves differently, and to bring happiness and a sense of fulfillment into every home.” Oprah’s mantra—“Live Your Best Life”—connects with many American women’s aspirations. This is the essence of Oprah, and it informs all aspects of her “brand”: the advice she doles out on health, relationships, and sex; the products she selects for her “O list”; the content of her national speaking tours and workshops; the subjects of books she talks about.

Oprah’s ability to connect emotionally with US women has resulted in a high level of influence on their behavior and thinking. Like the books she recommends, the products that she selects for her annual holiday list of favorite things are also instant hits. Origins, a cosmetics supplier, has reported that the star seller of its holiday season was the A Perfect World intensely hydrating body cream with White Tea ($30 for seven ounces), one of Oprah’s holiday 2002 selections. Similarly, Chico’s, the specialty retailer of misses’ clothing and accessories whose $38 watch was featured on the same show, told Women’s Wear Daily that customers overwhelmed their stores and call centers following the show—and that 75 percent of calls were from new customers. Oprah’s influence has also paid off handsomely. Her net worth is estimated at about $1 billion, and her show and magazine generated revenues of about $300 million and $140 million, respectively, in 2001.

Martha Stewart’s enterprise, Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, evolved in reverse order from Oprah’s, starting with the magazine Martha Stewart Living and then moving into television. Living, with 2.4 million paid subscribers, still runs a close second to O, and her shows, Martha Stewart Living and From Martha’s Kitchen, are viewed by millions of households. Martha focuses on eight categories—Home, Cooking and Entertaining, Gardening, Crafts, Keeping, Holidays, Weddings, and Baby—and calls herself “America’s most trusted guide to stylish living.” Even during her trial and after she stepped down as head of her company, her popularity and influence did not significantly decline, although her company’s share price did. As one woman said to us, “Martha is one of the first people who said your home is important. She gives the family validity. She is a source of comfort.”

Goods and services play a prominent role in the activities of both women. Oprah’s message is directed primarily at the individual; she talks about self-improvement and self-actualization, about taking care of yourself and “being worth it.” Although she is less linked to products than Martha, she urges her followers to look after Spirit and Self, Relationships, Food and Home, Mind and Body— and not feel guilty about what it might take to do so. Martha is more of a social facilitator who helps people express themselves and make more fulfilling connections with their family and friends. She markets products under her own brand name, and she openly and unapologetically promotes her many commercial partners and sponsors. These two women have played a key role in the trading-up phenomenon. Oprah has said it’s okay to trade up. Martha provides the how-to.

American consumers have a large array of other sources that offer examples of fulfilling and exciting lifestyles (or so they seem), often scattered with premium goods. Television shows regularly mix entertainment with consumption, from Sex and the City (now in reruns) to Queer Eye for the Straight Guy and What Not to Wear. We have celebrity chefs, businessmen, authors, and athletes. Thanks to incessant media exposure, we know how these celebrities live, the activities they engage in, the goods they use, and the products they endorse. We know we can’t be them, and we don’t really want to be. But we will take cues from them and sometimes associate ourselves with goods and services they find worthwhile. If we use the clubs they use or wear the clothes they do, a little bit of them rubs off on us.

A Mix of Benefits and Stresses

These shifts in our society have given American consumers greater purchasing power, consuming knowledge, and a broader range of goods to buy. They feel excited by the possibilities and want to experience as much of life as they can. They aspire to live well and enjoy themselves, be healthy, and achieve prosperity for themselves and their families.

The findings of our survey of 2,300 American consumers making $50,000 or more per year—including people of all demographic descriptions—show that people are highly aspirational and want to feel good about themselves. A majority of respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the statements “I am happy with my life right now” (62 percent) and “I have peace of mind” (55 percent). The statement that achieved agreement from the highest percentage of respondents (64 percent) was “My home is my castle.”

But their general statements of happiness are slightly belied by their responses to questions about more specific aspects of their lives. Only 39 percent agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I have the right balance in my life”; 37 percent with the statement “I feel like a part of my community”; 35 percent with the statement “I have a lot of close friends.”

These darker underlying themes become more dominant when consumers talk about specific aspects of their lives. Americans are working longer hours, and work intrudes more into their personal lives. Relationships are difficult to maintain, and divorce is on the rise, owing in part to our work stress and intense lifestyles. Job security is rare, and employee loyalty scarce. There is so much choice, it can be dizzying. People feel pressure to compete with each other for the most rewarding jobs and most attractive partners. We fear that we won’t measure up, will lose out, get sick, look stupid in front of our peers and colleagues, somehow fall into ruin, and lose it all.

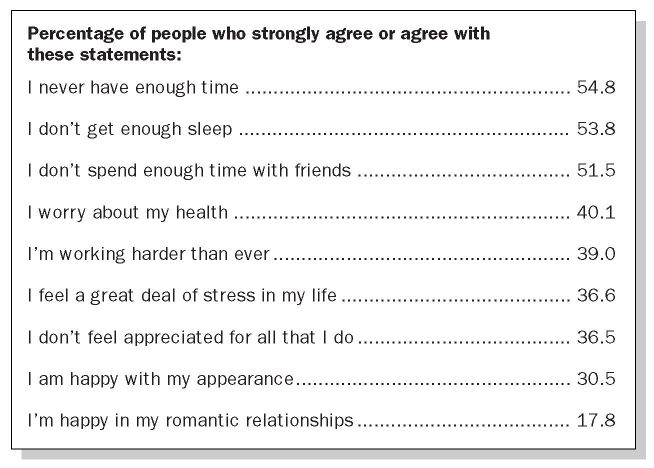

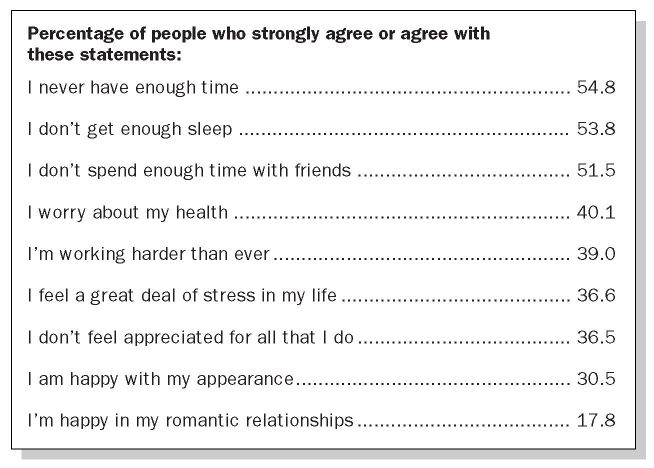

In our survey, 55 percent of respondents agreed that “I never have enough time,” and 54 percent agreed that “I don’t get enough sleep.” Nearly 40 percent said they are “working harder than ever,” and 37 percent said, “I feel a great deal of stress in my life.” A sig-ni

Our survey of 2,300 consumers showed that many Americans feel overwhelmed,isolated, lonely, worried, and unhappy.

ficant percentage of the respondents said that they don’t spend enough time with their friends (51 percent) or family (35 percent), that they worry about their health (40 percent), and that they are anxious about the future (40 percent).

The picture thus becomes a little fuller—of consumers who say they are generally happy, possibly because they want to believe they are, but who also feel pressed for time, stressed by work, and out of touch with people who are important to them. In addition to personal stress, our society is going through difficult and complex economic times, as is the world, with more acts of terrorism, war, and other kinds of unrest. Accordingly, many Americans see it as a kind of civic and patriotic duty to keep spending. Kim, a twenty-six-year-old woman who lives with her boyfriend and has a household income of $80,000, says, “I think we are in scary times right now, financially and in the world. But I think you cannot stop spending money because that is just going to put us in a worse place than we are now. I want people around me to be employed. The way I look at things is: Go out and support businesses. I think that helps everybody.”

The survey respondents agreed that there is a connection between these emotional concerns and their buying and consumption behaviors. More than a third (36 percent) agree that “I love to shop,” and 29 percent think of shopping as a “form of stress relief.” When asked about consumption in specific categories, they expressed far more enthusiasm. Seventy-five percent of our respondents said they “love to travel,” and 64 percent said they “love to try new foods.” Sixty-five percent said that “in the areas I spend more for quality, I know all the fine details.”

So the complex and sometimes conflicting nature of the New Luxury consumer becomes evident: A majority of our respondents say they are happiest at home, but they say also that they love to travel. Only a third say they really like to shop, but two-thirds say they are expert in the goods they care about.

The spending behaviors in specific categories align with the emotional interests. We asked the respondents to consider twenty categories of consumer goods and indicate the ones in which they would be “likely to spend more to get a product that is better than the rest.” The home or apartment topped the list, and many home goods were among the top twelve, including furniture, home entertainment, personal computers, bedding, kitchen appliances, laundry appliances, and cookware—as you would expect of consumers who are happiest at home and consider their home their castle. Sit-down restaurants ranked second. Cars, shoes, and apparel are also categories where many consumers say they will spend more. Consumers at every income level are rocketers. Ninety-six percent of the respondents say they have at least one category they are willing to pay more for; 51 percent admit there is at least one category in which they “spend more than I should.”

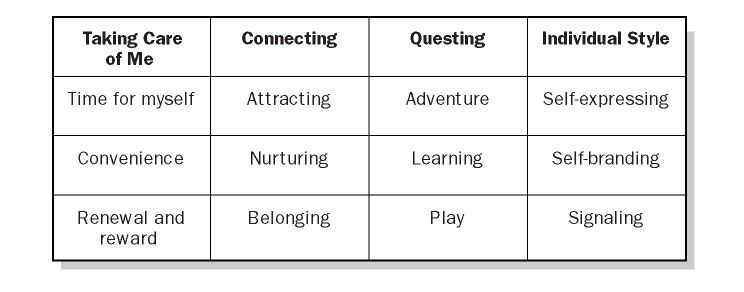

The Four Emotional Spaces

The most intriguing findings from our survey are about how buying certain categories of goods makes consumers feel. Respondents were asked to choose from a list of forty-four terms that describe how trading up in their category of choice made them feel. These terms “pooled” into six distinct groups, which we combined into four “emotional spaces”: Taking Care of Me, Connecting, Questing, and Individual Style. Each category has a dominant emotional space associated with it—personal care is primarily about Taking Care of Me, for example—but some categories, such as the home, are important in all four of them.

Taking Care of Me: Well-Being, Beauty and Youthfulness, Making Time for Myself

This emotional space is the most personal and immediate and, for many American consumers, the most important. It is about goods I buy to make me feel as good as I can, as immediately as possible. It is about physical rejuvenation, emotional uplift, stress reduction, pampering, comfort, rest, and moments to myself. It includes such goods as personal-care products, ice cream, chocolates, coffee, home-theater equipment, appliances, furniture, and bedding.

Because these activities are so personal, they are sometimes thought of as selfish, self-indulgent, or guilty pleasures. Working women and working mothers, in particular, feel the most need for such comforts, as well as the most guilty about indulging in them, especially if it means reducing time spent with or doing things for the family. However, their stresses are so high and the cultural permission has become so explicit that they are buying extensively in these categories.

Paula, fifty-eight, has had a life with more than its share of difficulties, including two divorces and health issues such as heart surgery and a bout with breast cancer, all of which she handled while raising two kids and holding a full-time job in a university library. The job pays about $40,000 a year. “It took years for me to realize that a mother is not the person who is supposed to work until dawn getting things done for other people,” Paula told us. “I went to a therapist, and she would ask me, ‘What have you done for yourself this week?’ And I would think to myself, ‘What a stupid question,’

because I was not even to the point where I thought I could do something just for myself.”

When women find a few moments for themselves, they like to make the most of them. Sometimes they retreat to the bathroom or in-home spa, where they can feel safe, comfortable, warm, relaxed, and reasonably certain they will not be disturbed. They are likely to take with them one of a number of New Luxury goods. They may soak in Aveda Soothing Aqua Therapy, whose “fragrant combination of Dead Sea salts, plant-based emollients, vitamin E, and beneficial essences turns a bath into an indulgence” at $34 for a sixteen-ounce jar. A scented candle from Yankee Candle ($19.99) may flicker on the edge of the tub. They may sip a glass of Kendall-Jackson Grand Reserve Chardonnay ($20 for the 750-milliliter bottle) or enjoy a Godiva Dark Chocolate Ganache. (Paula is especially fond of chocolate as a form of Taking Care of Me. “One good piece of chocolate is worth twenty-two Hershey’s bars,” she says.)

Even in moments of such personal indulgence, moral and social values come into play. Melissa buys Aveda personal-care products because “they are very environmentally conscious. Even though I’m ‘trading up,’ if a company is environmentally conscious, I’m much more apt to purchase from it, and my husband has no problem with me going to Aveda and buying more expensive products there. You can buy a bottle of Suave for two dollars. The shampoo I buy from Aveda is nine dollars.”

Men, too, seek moments alone but are more likely to retreat to a room equipped with a personal computer, a premium sound system, or a home theater. Anna, thirty-three, bought her husband, Roy, a Sony home theater system as a Christmas gift so he could “have a room in the house that was his own personal space and getaway.” With a household income of $63,000, she spent about $3,000 on a six-speaker Sony Dream System, but even so, it represented a trade down. She really wanted to buy the Bose system, but it was “just way too expensive for me.”

Taking Care of Me goods are also tools that help busy consumers leverage their time better. These include restaurant dining, premium convenience foods for consumption at home, and laundry appliances that make doing the wash easier and less time-consuming.

The toll of stressful careers on American consumers, especially those in high-stakes professions, can lead to physical exhaustion, illness, and more. Emily and her husband, Paul, both lawyers, lead a stressful life. “Paul and I both have jobs that are very stressful because of what’s at stake,” Emily told us. “With Paul’s job, what’s at stake is somebody’s life. It’s an insane amount of stress. If he screws up, somebody’s going to jail. Or worse. For me, it’s the fear that if I screw up, if I do something that makes my boss say something that’s wrong and it’s out in the press . . . Good Lord!”

One solution for this couple is eating well. They dine out several times per month, often spending $50 or more for a dinner for two. They’re not alone in this stress-management solution. Over the past decade, annual restaurant visits per capita have risen from 153 in 1991 to 178 in 2001. The total spending per visit is also on the rise, up 4 percent in 2000 over the year before.

Consumers also spend more on ingredients that they believe make dining at home more healthful, fun, and sensuous for themselves and their dining companions. Kim, twenty-six, has lived with her boyfriend for three years, and they have a high household income, $80,000, with few expenses. They seek rejuvenation and connection by dining at home. They watch the Food Channel regularly and Kim likes to shop at a specialty grocery near her apartment in St. Peters-burg, Florida, where she buys ingredients such as organic vegetables for new recipes. “I cook probably five nights out of the week,” says Kim. “I love it. We feel very lucky that we can afford to shop there.”

But not all trading up in food is to organic vegetables and exotic ingredients; many Americans think of ice cream as a major food rejuvenator and are eating premium ice cream at the expense of the “healthier” ice cream alternatives, frozen yogurt, sorbet, and tofu treats. They want the uplift and refreshment that come with the intense tastes of Edy’s Dreamery, Starbucks, and Häagen-Dazs. Ben & Jerry’s offers ice cream in some fifty flavors and forms, providing for a great deal of personal variation and individuality. As a result, the average price per pint of ice cream has risen 26 percent since 1997. However, to compensate for the additional calories, consumers are buying the premium ice cream in smaller containers. Pints and quarts are growing in popularity while the larger sizes are growing in sales at a slower rate. These superpremium ice cream brands contribute a disproportionate amount to the profits of the entire category. We estimate that a pint of Ben & Jerry’s earns about $0.92 profit per pint in comparison to $0.14 contributed by a pint of a typical conventional brand made by Dean Foods, whose brands include Dean’s, Oak Farms, and Mayfield Dairy Farms.

Well-being is also the story behind the success of spas such as Canyon Ranch. Mel Zuckerman, who with his wife, Enid, cofounded Canyon Ranch, says that their goal has been to create places that can bring a “sense of safety, peace, pleasure, and warmth.” Canyon Ranch combines the physical rejuvenation that comes from any respite from work with “self-discovery, health-consciousness, individual empowerment, and lifestyle medicine.” This “intersecting” of emotional spaces leads to a powerful personal experience.

A Canyon Ranch facility is designed to be an experience of physical, emotional, and spiritual attention and improvement. The emotional engagement is so strong that Canyon Ranch visitors become apostles. They tell their friends, neighbors, and colleagues about the “life change” they have experienced and often talk about their lives as they were “before the Ranch” and as they have been improved “after the Ranch.”

Zuckerman told us that he did not understand the full potential of his concept at first. He began the business as a personal mission. He wanted to get away from the pressures of being a homebuilder in an up-and-down market and to improve his health. He also wanted to create a business where he and his wife could work together to help people and change lives. By taking care of himself—rejuvenating his own life—Zuckerman created a hugely successful business. With 350 guests paying up to $6,000 per week, each Canyon Ranch delivers an estimated 20 percent operating margin. Sales of ancillary materials including videos, cookbooks, equipment, clothing, and cosmetics add another 5 percent to gross revenues.

Now the Zuckermans are doing what all New Luxury creators do—seeking to expand their reach and extend their concept to serve new consumers: families, singles, teens, and short-stay travelers. In addition to the original spa in Tucson, there is now a Canyon Ranch on the Queen Mary II, a hotel/residence in Miami, and a casino hotel in Las Vegas. They want to develop and offer new products: vitamins, nutritional supplements, and skin products. They are constantly offering new activities, including golf and skiing, and educational programs, such as a tantra workshop in sexual health.

Although the original Canyon Ranch borders on Old Luxury, the success of Canyon Ranch has helped transform the category from a minor industry into a major phenomenon. The number of spas in the United States has almost doubled since 1997, and the number of spa visits in the United States has more than tripled. In 2003, revenues from the spa industry in the United States exceeded $14 billion. Part of the reason for the remarkable growth in this category is a shift in the way consumers perceive spas. Many have come to think of the spa as an essential and regular part of their health, fitness, and beauty regimen, rather than as a place for occasional pampering.

Spa services are no longer designed for, or enjoyed by, only the elite and superrich. Although spa-goers typically are affluent, with annual incomes above $72,000, spas offer a wide variety of services, from yoga classes at $15, to a $60 massage, to $199 for a Botox treatment, that are affordable by almost anyone. Jerrilyn Boyd-Hadley, a massage therapist at Athena Health Club and Day Spa in Brent-wood, Tennessee, says, “We are serving more and more working women who don’t have a lot of money, work nine to five, but know the importance of pampering before going home to the kids.” Steven Ludwig, president of A Moment’s Peace Day Spa in Cool Springs, Tennessee, agrees. “We have a schoolteacher who comes in every Saturday. She doesn’t have a ton of money to throw around, but she wants this to be part of her lifestyle. It’s that important to her.” Wendy Randall, a married, working mother of two young kids, makes room in her schedule and in her budget for spa time at Natural Oasis Day Spa and Salon in Spring Hill. “This is for my sanity as well as for relaxation. The first time I went, I came home so happy that my husband said I should go once a month.”

The fastest-growing segment of the industry is composed of spas located in hotels and resorts, with 237 percent growth in the number of such establishments in the United States between 1997 and 2002. In 2001, revenues from resort and hotel spas reached about $2.4 billion. So many travelers now think of a spa as an important hotel amenity, industry insiders predict they will become as common as minibars and high-speed Internet connections.

As spas have grown in popularity, they have also added new services, such as aromatherapy, body scrubs, and, in a notable trend, medical services. These “medispas” combine medical treatments with luxurious personal care. Some medispas are contained within larger spa resorts, and offer cosmetic treatments, such as laser hair removal. Other medispas are run by cosmetic surgeons who expand their offices with massage rooms and nail bars. In 2002, there were some 225 medispas in the United States, with combined revenues of about $205 million.

One of the reasons for the growth of medispas is the development of affordable and minimally invasive procedures such as Botox injections, microdermabrasion, and laser hair removal. These procedures are well-suited to the medispa environment. Consumers like having an M.D. on the premises, rather than just a minimally trained cosmetician. They feel less fear in the comfortable, nonclinical surroundings than they might in a hospital, and they like the lower prices associated with a spa when compared with a full-service hospital.

Spas of all kinds appeal primarily to the Taking Care of Me emotional space. A majority of spa-goers report that they go to spas to relieve stress, feel relaxed, to indulge themselves, or to feel better about themselves. In a study conducted by the International Spa Association in 2003, 93 percent of spa-goers said they felt better after their most recent spa visit, 71 percent felt more relaxed, and 50 percent felt energized. Thirty-three percent of women said they left the spa feeling “more attractive,” and 24 percent said they felt “more confident.”

So, New Luxury goods bring a measure of relief and comfort into a world that can be harsh and uncertain. Americans have become far more aware of the frightening possibilities that surround us—we live with heightened fears of terrorism, war, and other conflict at home and abroad. We also live with a persistent concern about the national and global economy. As we learned from our survey, about 40 percent of the respondents are “worried about the future.” But even in the face of uncertainty—especially in the face of uncertainty—Americans don’t want to spend their money on bland, emotionally empty goods. They want to spend on items that bring emotional engagement, from spirits to nice sheets. Why not? As Frances puts it, “There’s a part of me that feels like, ‘Spend some money. Have some fun! You’re going to die tomorrow.’ ”

Connecting: Attractiveness, Hooking Up, Affiliation, and Membership

Connecting is as important as Taking Care of Me for American consumers, and New Luxury goods are instrumental in helping to make connections and keep them strong.

The rules and practices of dating have changed dramatically in the past twenty years; today, for many singles, dating is a marketing exercise that must be undertaken with great seriousness. Would-be connectors seek every possible advantage through the savvy use of goods. There are new dating rules. While it is mostly women who make up the rules and enforce them, females can get just as frustrated and confused by the process as men. This is primarily because they are generally more interested in marriage than men are; although both women and men are delaying marriage, men delay longer. These facts take on particular significance when viewed in the light of long-term changes in sexual behavior. The most sexually active women are eighteen to twenty-nine years old, and the great majority have had their first sexual intercourse while in high school. So, because most women (as well as men) come into their dating years with early sexual experience and because they are delaying marriage, the median time between first sexual encounter and marriage has dramatically increased, from 1.3 to 8.1 years. That means the period of active dating is very much longer than it used to be.

Even though the window for “hookups” is longer, the pace of the dating game has not slowed, and the business of finding a lover who might become a suitable mate seems as fraught as ever. This is partially because of the greater sophistication of the dating “consumer”—people are seeking the best possible companion available, and thanks to the popular media, they have a much larger pool to evaluate, at least virtually. It’s also because everybody is so pressed for time—working harder, doing more, trying to cram more of everything into life. Accordingly, the dating process has been streamlined and facilitated via a number of new methods, including dating services and Web dating.

Because daters are so pressed for time, they look for ways to make the process work most effectively. One way to do so is to use goods to send prospective partners signals that help communicate who you are and what you’re looking for. But “sending signals” is not simply about showing off wealth, as it might have been in years past. The National Marriage Project reports that men are put off by women who overemphasize material goods: “They resent being evaluated on the size of their wallet, their possessions, or their earnings.” However, many daters don’t mind signaling the size of their income in subtle ways. Alvaro, a twenty-six-year-old administrative assistant earning $35,000 annually, says that when you call for Ketel One vodka, “you might as well hold out your dollar bills and fan yourself with them.”

More often, however, the language of goods in dating is about signaling our taste and knowledge, achievements and values, and those qualities are the very basis of New Luxury things: the liquor we order, the lingerie and clothing we wear, the jewelry and accessories we display. But it is not only a language of display; it is also the New Luxury objects and experiences we talk about—from a description of a wine we enjoy to describing a trip we took. It is very unlikely that conventional middle-market goods will be referenced in dating conversations. “I really love to drink Gallo jug wine” or “I wear Sears chinos” may be telling statements, but they’re not very impressive.

New Luxury goods are tools of attraction not just for young daters and those in the marriage market for the first time; they are also sought by people who have divorced or suffered a breakup. As Carrie Bradshaw, the lead character of Sex and the City, puts it, “Breakups: bad for the heart, good for the economy.” Today, the likelihood of such breakups is higher than ever. Dating couples say they are less likely to stay together for very long if the relationship is “not the real thing” and on the road to marriage. For married couples, the likelihood of divorce within the first ten years of marriage increased from 20 percent in 1973 to 33 percent in the year 2000. In 1996, the lifetime probability of being divorced for a twenty-five-year-old was 52 percent.

Newly single consumers tend to be ardent consumers, especially if they feel they have been wronged. Women spend on apparel, jewelry, cosmetics, spirits, and dining out. Men tend to spend on electronics and cars. But sometimes after a breakup, the spending habits change permanently. “As a kid, we used to go for quantity, not quality,” says Melissa. “Now, with my parents’ being divorced, my mom has changed a lot in terms of her views toward luxury and what she’s willing to buy for herself. She definitely indulges more than she ever did before.” When people are hurting, especially after something as intense as a romantic breakup, goods bring solace, comfort, reward, revenge, and some measure of self-esteem.

The use of goods to facilitate connecting continues even after marriage, and among all members of the family, including the children. The primary reason is time. In many families, family members may find very few moments to spend together. They want to be sure the experience is as rich and rewarding as it can be. When family members cannot spend time together, goods can act as a compensation, even a substitute for the lost moments—sharing a cup of Starbucks coffee, eating a gourmet take-out meal, spending time in front of the Sony home theater, or listening to music on the Bose Wave radio.

Dorothy, forty-five, has never been married and has no kids, but she is very close to her eight-year-old niece. They spend a lot of time together, reading and attending cultural events. Dorothy also likes to buy nice things for her niece, such as clothing and lunches out. Next year, they plan to go to American Girl Place in Chicago (they live in Indiana) to buy a doll and accessories. “Because I have no children and she is my niece and the only one I have, I am willing to spend that amount of money for something special,” says Dorothy, who earns $55,000 as a librarian. “I think every little girl should be able to experience that one time in her life. That’s what aunts are for.”

New Luxury goods also provide a way for consumers to align themselves with people whose values and interests they share—to make affiliations and “join the club,” whatever it might be. “When buying things that are just for myself,” says Jack, a business supervisor earning $70,000 a year, “I can easily trade down if I have to. But when it comes to social things where I’m out with a group of people, it would be a lot harder for me to say, ‘Well let’s not go to Panera because it’s too expensive. Let’s go to Subway.’ That would be harder for me to give up.” Charles, a fifty-five-year-old real estate developer, agrees. “One of the reasons I buy premium wine is because we have some friends who will look at and value that if we serve it.”

A search for affiliation sometimes combines with the expression of Individual Style. Miguel, thirty-one, works for a nonprofit organization in Colorado and earns $70,000 a year. He is single, owns a home, and has already saved more than $100,000; he has no credit card debt. “Both of my parents come from very poor backgrounds, with very large extended families,” he told us. “But they wanted a different life for their kids. They understood the pains of not having an education and all the troubles that can go with that.” Miguel was born in Mexico, but his parents moved to the United States, and he and his siblings were brought up in a predominantly white, middle-class environment. His parents worked hard to make sure that Miguel had the clothing and accessories that would help him fit in with his new group. “If I wanted the fancy-cut jeans or the fancy Guess? shirt, I could get that, and it would not be a problem. We took vacations, and my dad always had a really nice car. Those luxuries were important for my parents and for us kids, so we would not feel that much different and we could fit in and do the things the other kids did.” Miguel is still conscious of fitting in and will buy premium goods—including clothes, cologne, watches, and other personal accessories that he purchases at stores such as Dillard’s, Neiman Marcus, and Saks Fifth Avenue—to show that he belongs to the ranks of the successful and has good taste.

Questing: Taste, Adventure, Learning, and Play

Questing is the emotional space that has emerged the most strongly in the past several years. It is all about those goods and services I can buy that will enrich my existence, deliver new experience, satisfy my curiosity, deliver physical and intellectual stimulation, provide adventure and excitement, and add novelty and exoticism to my life.

Questing is about venturing out into the world, experiencing new things, and pushing back personal limits—and travel is the most popular way to do so. Seventy-two percent of the respondents to the survey told us they “love to travel,” and as we’ve seen, Americans are traveling more than ever before, primarily to Europe and Asia. But the focus on Questing means that the nature of travel has changed: New Luxury consumers want to experience travel that does more than give them a rest and a getaway. Seventy percent of our respondents also said that “knowledge is the greatest luxury.” They want to combine travel with knowledge gathering, acquiring new skills, and collecting memorable experiences.

This has led to the rise in adventure and experiential travel. What else could explain the popularity of what Newsweek calls “authentic holidays”? Consider, for example, a camping visit to eastern South Africa, hosted by a group of native people, where dinner is a stew of pumpkin leaves and dumplings and the entertainment is listening to tribal folktales around the fire. Although beach vacations are still the most popular, the World Tourism Organization predicts that sport- and nature-based vacations to new and lesser-known destinations will have the most growth. They project a threefold rise in total trips worldwide between 1995 and 2020, with the greatest growth in trips to East Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.

In our interviews, travel was a recurring theme and topic of enthusiastic discussion. Barbara and her husband, James, with a household income of over $200,000, travel extensively from their home base near San Francisco. “I like to go to countries where I do not feel like I would be real familiar with the lifestyle,” says Barbara. “In Belize, we went into the rain forest and tubed five miles down the river through lots of caves. We swam with manatees and sharks and stingrays and did a lot of adventurous things.” Miguel regularly travels for business, and “that has encouraged my desire to travel for fun and for pleasure as well,” he says. “It gives you a little bit more of a worldly perspective. It gives you a sense of being refreshed, and it is almost like a badge of honor that you can wear when you come back. People are buzzing about your trip, wanting to know what it was like and what you did.”

The yearning to quest is also fulfilled by traveling to destination spas in far-flung locations such as Banyan Tree in Thailand, Ananda Spa in the Himalayas, and Rancho La Puerta in Mexico. Spa-goers also think of trying new and exotic treatments such as Chi Nei Tsang, shiatsu, and acupuncture as a form of questing.

The interest in Questing has brought dramatic change even to a travel category that has long been the epitome of Old Luxury: cruises. Today, cruises are becoming an affordable luxury for middle-market consumers. Almost 7 million North Americans took a cruise in 2001, up from just over 3 million in 1988. Half of all cruisers had household incomes of $65,000 or less. During the 1990s, cruises grew twice as fast as all other types of vacations, achieving a 6.2 percent compound annual growth rate since 1988. The popularity of cruising has risen because cruise operators, such as Carnival Cruise Lines, have successfully slashed the average cost per day of a cruise by nearly 30 percent and have added nearly 7 percent capacity each year. They are also offering more short cruises, making the real cost of a voyage even lower. But most important, the cruise operators are striving to connect with the emotional needs of their customers. They have incorporated services and activities that relate to Taking Care of Me. Orient Lines, for example, offers a spa experience that emphasizes relaxation and pampering with treatments that include steam wraps, Swedish and shiatsu massage, seawater therapy, and foot massages on deck.

Cruises are also, of course, about Connecting. Conquest, Carnival’s largest “fun ship,” has twenty-two bars and restaurants to explore, providing plenty of opportunities and options for meeting and evaluating potential partners and playmates. With some 3,000 passengers aboard, it’s like a four-day dating event with 1,500 candidates to choose from.

Cruises traditionally have been about food, but food in the Old Luxury tradition—indulgent, not particularly healthful, and “sinful.” Although food is still a central part of the cruise, it is less about gluttony and more about exotic, gourmet, or healthy dining—about Taking Care of Me, Connecting, and Questing. The Nautica Spa aboard the Conquest offers a “healthful, low-fat” menu. Seabourn Cruise Line offers menus designed by “celebrity chefs” such as Charlie Palmer, chef of Aureole in New York.

When New Luxury tourists travel, their eyes are open to goods, services, styles, and tastes they might not encounter at home, and collecting interesting and meaningful goods is very important to them. As Nicole puts it, “What really drives me, and my husband too, is feeling part of an underworld of stories. Like, ‘Oh, we got that piece when we were traveling here, and we got that piece in the night market in Hong Kong.’ We love to do stuff like that because it is cool.” This influx of “hand imports,” as well as stories and ideas shared with friends about goods sampled abroad, has a tremendous influence on the market. People become interested in goods that capture the essence of foreign and exotic places, especially places they have personally visited. Barbara, for example, likes to incorporate her travel experiences into her cooking. “We buy sauces and seasonings every time we travel. I’ll use some sauce that I bought in Belize for a dinner party I’m having for friends of mine who really enjoy hot foods. I am re-creating a typical dinner from Belize, with the same types of side dishes and a jerk main course.”

Individual Style: Achievement, Sophistication, and Success

Although New Luxury consumers are not driven primarily by a desire for status or empty infatuation with a brand name, that does not mean they care nothing for the messages that goods and brands deliver about their Individual Style. “Luxury is good,” says Rebecca, “because it allows people to express themselves.” Consumers know they can say a lot about themselves through their choice of specific brands and types of goods. As Dennis explains, “One of the characteristics of luxury brands is that the consumers, maybe not all of them, but certainly a better-than-average chunk of them, go to some extra trouble to educate themselves about the brands and what they offer.” So, rather than purchase because of the brand name, New Luxury consumers often purchase specific attributes that cause them to appreciate and stick with a brand.

In some categories, such as cars, brands are extremely important to expressing Individual Style. This is partially because the advertising messages contained within each brand have been sharply defined and repeated a million times over. Even if we don’t exactly believe in what the advertisers tell us, we are aware of the messages and know that others know them, too. For those brands where the advertising messages connect with the reality that the consumer experiences, the brand identity can become exceptionally strong. BMW, for example, has established itself as the “ultimate driving machine,” which may sound innocuous until it is analyzed in the context of competitive models. The BMW brand is all about driving, which is an activity involving mastery and adventure, and not about comfort or luxury. And the emphasis on the “machine” reinforces the primacy of the BMW engine, which is the soul of the brand and has been since its inception.

Brands play an important role in creating an Individual Style that sends messages to all kinds of people—including potential employers, colleagues, friends, lovers, and family members. Brands provide a reasonably reliable, efficient, and consistent method for signaling others about who I am or who I would like to be. These signals tend to be most important in brands that are mobile, whether worn or carried: goods such as shoes, clothing, spirits, fashion accessories, and watches. Self-branding through association with brand names can be tricky because of the speed of the fashion cycle. Messages can change quickly, and brands can become distorted in meaning. Kathy told us, for example, “I do not care about the brand name with clothes as much as I do with makeup or with accessories. With accessories, I value the brand. But fashion comes and goes. I could cut back in that area and buy more things that I like rather than just the most expensive items.”

New Luxury consumers are very careful to align themselves with brands that they have a genuine affinity for and that are a good match for their own Individual Style. Jake took note of our own set of Callaway golf clubs and, after watching our first drive, remarked, “Those clubs are too good for you.” Because consumers can be so expert in deciphering the messages contained in brands, the consumer risks appearing superficial or foolish in basing an Individual Style on an inappropriate brand, or buying a name brand that he knows little about. However, when consumers purchase brands that are meaningful to them and align with their own activities and values, the combination can be powerful. Martin, a scientist earning more than $100,000 annually, enjoys hiking, skiing, trekking, and other kinds of adventure travel. He wears premium Patagonia clothing, not only on his adventures, but also to his office and to social events. For those who know Martin and admire him, the devotion to Patagonia clothing does not seem silly, but an endorsement of the brand by an appropriate apostle. It is very much a part of his Individual Style.

The home is a place for status purchasing, and it’s an important expression of Individual Style. A New Luxury kitchen often has a six-burner cooktop, griddle, triple ovens, warming drawer, side-by-side or walk-in refrigerator, wine refrigerator, and more, from companies such as Viking, Sub-Zero, Gaggenau, Jenn-Air, and others that consumers value for their look, features, and values. They are expressions of Individual Style as much as they are tools for living. Some 75 percent of the Viking cooktops installed are never used, but the owners are proud of them and think of them as expressions of their interest in Questing, as well as good investments.

The Limits of Emotional Engagement with Goods

Any “map” of human emotional needs is simplistic; ours is meant as a tool to help consumers and creators of New Luxury understand the key impulses behind most purchases. The emotional spaces are closely related and do not have sharp boundaries between them. Sometimes the spaces are in conflict.

And there are other elements that come into play in the emotional spaces, including morality and values. We are not totally selfish beings, and we feel a strong sense of responsibility to other people, our country, and our world environment. As lawyer Emily says, “We acknowledge we like nice things, and we have an incredibly nice lifestyle. We try not to feel guilty about that, but we also try to be conscious of the fact that we’re part of a broader society and community and try to make sure we give to charity and donate money.” It’s important to New Luxury consumers that the goods they buy reinforce their good intentions toward the world. Judith buys premium imported foods, for example, because “European countries have stricter laws about using genetically modified seeds. They use fewer pesticides and herbicides, fewer antibiotics and hormones in raising livestock.” Melissa’s boyfriend does the same. “He’s adamant about being socially conscious and going to the local food co-op. I very much support that, but when you’re buying organic raspberries at $8 a pound, you think, ‘Oh my God. We’re spending $130 on groceries that would probably cost $60 somewhere else.’ Yet he sees nothing wrong with that because he is making a conscious choice to be ecologically sound and also healthy.”

New Luxury consumers, therefore, are complex creatures. They have wealth and sophistication. They are driven by fears but have high aspirations. They want it all, but they are often exhausted by trying to get it. They spend liberally on themselves, but they also believe they should do right for the world. They rocket, they trade up, and they trade down. They follow fashion and scoff at it. They buy for individual style and a little bit for status. They are highly influenced by their friends and cultural figures, but they have strong tastes of their own. They will try almost anything, but they give their loyalty sparingly. They don’t believe in debt, but they don’t let money stand in the way of buying what they want. They love objects, but they don’t believe in conspicuous consumption. New Luxury consumers need a lot of understanding. When they get it, they are not only appreciative, they are also likely to open up their pocketbooks and spend. They are a growing force of consumers—one to be reckoned with.

And New Luxury goods are more than simply objects of consumption. They have become a language, a nonverbal method of self-expression and social dialogue. The language enables consumers to say, “I’m intelligent and discerning,” in many different and individual ways. In a country as large as the United States, encompassing great regional differences and composed of people from many cultures with many different languages, it is not surprising that we have sought to unify ourselves through the common language of goods. There is more complexity, interest, variation, and subtlety in New Luxury goods than in conventional products (an ordinary washing machine, a Budweiser) or even in Old Luxury goods that often call more attention to themselves (a Gucci handbag) than to their owners.

For sophisticated and discerning spenders, New Luxury goods provide a rich and broad vocabulary with which to speak—without saying a word.