Three

The Creators and Their Goods: Definitions, Forces, Practices

Who creates New Luxury goods?

Very often, they are created by a leader who is an outsider to the category. Ely Callaway spent thirty years in the textile business before he entered the wine business and then, at the age of sixty-three, created Callaway Golf. Pleasant Rowland had been a teacher before she created the American Girl doll. Fred Carl Jr. was a homebuilder before his wife challenged him to develop a better stove, now known as the Viking. Jim Koch was a management consultant (with The Boston Consulting Group) before he created Samuel Adams Boston Lager beer.

But New Luxury goods can also be created by an established leader or industry insider who has the rare ability to think like an outsider. Joe Coulombe had been in the grocery business for almost ten years as founder and leader of a chain of convenience stores called Pronto Markets before he transformed it into Trader Joe’s. Leslie Wexner had long experience in the apparel industry when he purchased a small lingerie business and transformed it into Victoria’s Secret. Ronald Shaich was CEO of Au Bon Pain but was able to see that his acquisition, the Saint Louis Bread Company, had more potential than his original brand. Joe Foster, a director at venerable laundry-appliance maker Whirlpool Corporation, took a risk on a European-style front-loading washer-dryer combination—long considered by industry insiders as a nonstarter in the American market—and built it into a remarkable success.

Outsider thinking is important because it enables the entrepreneur to wriggle free of that constricting assumption of the industry insider: the conventional price-volume demand curve. The industry insider is so used to the standard formula of “how many units” can be sold at “what price point” that it becomes hard for him to imagine that a premium product can move off the standard demand curve and sell at significantly higher volumes and higher margins. Outsider thinking also enables the entrepreneur to import ideas and practices from other industries and cultures and apply them to every aspect of strategy—including product development, pricing, consumer profiles, organization, and marketing.

In addition to their outsider thinking skills, New Luxury leaders have a facility for “patterning.” They are keen observers who are able to analyze the elements at work in an industry and see those that are missing as well. They make connections between elements that have not been made before and then create a new frame of reference for themselves and the category. Wexner told us, “I have to see a lot of things and then somehow I just make conclusions. If I see enough stuff, get out and around, I can put it into trends and put things together in funny ways.”

When these leaders come up with “funny” ideas, they are often rejected, even scoffed at, by industry insiders, colleagues, and friends. When Robert Mondavi announced that he planned to build the first new Napa Valley winery in thirty years, he “could hear the guffaws up and down the Napa Valley,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Everyone thought I was crazy.” Similarly, Wexner learned to live with the skeptical looks of his friends and colleagues. “I think they saw me as kind of a mad scientist until I was about fifty,” he told us. “My friends just thought I was nuts.” The difference between a mad scientist (or just a plain nut) and an entrepreneurial visionary, however, is that the idea is never enough—the entrepreneur is driven to make the idea tangible, a reality.

What differentiates and distinguishes the New Luxury leader is the personal nature of his mission and the emotional connection with his company. David Neeleman, founder of JetBlue, sold his charter airline to Southwest Airlines in 1993, joined Southwest as an executive, signing a five-year noncompete agreement. But he found he hated working at Southwest, although he admired the airline, and he was so disruptive there that he was fired five months after joining. According to a Forbes profile, Neeleman’s firing “opened old feelings of inadequacy,” which stemmed from early difficulties in school. While waiting for his noncompete to expire, he began dreaming of—and planning for—a new airline, which he referred to, simply, as New Air. In 1997, he was ready to go with JetBlue, which was launched in 2000. Neeleman’s commitment to JetBlue has an aspect of “I’ll show them”—and he has. (JetBlue, like Trader Joe’s, seems anomalous because of its discount price policy, but it qualifies as New Luxury because the company achieves high margins at high volumes, and it delivers the ladder of benefits, especially the emotional engagement of its customers.)

New Luxury leaders, therefore, tend to have an abiding passion for the product itself and are hands-on managers who get intimately involved in developing their goods and in promoting them in the market. Unlike the professional manager, who argues that he could run any business, New Luxury leaders want to create and build only a specific business whose products are of great interest to them. They really love their wines and golf balls, stoves and dolls, groceries and lingerie. Edward Phillips, who developed the premium Belvedere and Chopin vodka brands, spent two years researching vodka with the intention of creating a premium entry into a category that, at that time, had none. Ely Callaway played golf every weekend to promote his new products and see who was playing with which clubs.

This emotional connection to the core of the business makes for a leader who is very different from the executive whose decisions are based on more conventional concerns—such as what will advance his career, what will most likely be approved by the board, what is easiest to accomplish, what has “always been done,” what will please the analysts or press, or what will build the bottom line the fastest. New Luxury leaders are fascinating people who are as driven by their emotions as they are by a business plan. They are not always able to articulate how they accomplish their goals, but they are very clear about what they want to achieve and the things that are important to their businesses. Talking with these New Luxury leaders is to listen to people who look at the world through a lens of their own making, see patterns others do not, and are committed to making their vision a reality.

A Distinct Type of Goods

New Luxury describes a class of goods that have very distinct characteristics.

Old Luxury is about exclusivity. People who buy a Rolls-Royce do not wish to see a dozen other Rolls-Royce cars in the parking lot at Wal-Mart. New Luxury goods are far more accessible than Old Luxury goods, but their accessibility is more limited than conventional middle-market products. BMW sold about 213,000 vehicles in the United States in 2001, but General Motors, the quintessential middle-market carmaker, sold some 4.2 million. Similarly, Robert Mondavi sold more than 6,600 cases of its Woodbridge brand wines, at $6 to $10 per bottle, compared with 1,290 cases of its Robert Mondavi Coastal label, at $10 to $15 per bottle.

The challenge for New Luxury makers is to determine an optimal unit volume. If the goods become too available, they lose their sense of being limited in nature, and they will be unable to command a premium price. This is what happened, for a time, to Abercrombie & Fitch clothing. What started out as a New Luxury brand, with high quality and limited availability, quickly flooded the market and lost much of its cachet, especially to its original target consumer, the hip twenty-somethings. When they saw the A&F logo on the sweaters and jeans of fifteen-year-olds, the emotional connection with other cool people their age was lost.

Old Luxury goods are priced to ensure that only the top-earning 1 to 2 percent of consumers can afford them and to provide a large enough margin so their makers can be profitable at very low

unit volumes. New Luxury goods are always priced at a premium to conventional middle-market products—often as much as a tenfold premium—but are still priced within the financial reach of 40 percent of American households and not out of the question for 60 percent of them, those making $33,000 and up annually.

Some observers have interpreted New Luxury as a continuation of the quality revolution that began in the 1980s. New Luxury goods do, in fact, offer a high level of quality, usually higher than conventional middle-market goods and often higher than Old Luxury goods. The most basic definition of quality is “freedom from defects,” and that is a guiding assumption of New Luxury goods. Traders up expect New Luxury goods to be free of faults of manufacture or assembly and to perform precisely as promised. If the product has defects or performs inadequately, the consumer expects that it will be remedied, repaired, or replaced at little or no cost and with little or no hassle. Since most conventional middle-market manufacturers have also achieved high levels of quality, freedom from defects is not enough to distinguish a New Luxury product from its traditional rivals.

Old Luxury goods, by contrast, have not always been of the highest quality, at least as defined by American manufacturing standards; rather, they have been promoted as “handmade,” often by “old-world craftsmen,” even if those craftsmen are assisted by machines and advanced technologies. The Rolls-Royce is largely hand-assembled. Haute couture clothing is hand-stitched. Superpremium wine is handcrafted. Handcraftsmanship limits the unit volume that can be produced. It also introduces variations into the finished product that offer proof of the human contribution. The limited volume and the uniqueness of each piece help to justify the high selling price.

Many New Luxury goods have elements of craftsmanship, although they are not completely handmade or hand-assembled, and are therefore “artisanal” in nature. There are specific steps in production that require the human touch, or the process is modeled on traditional craft methods. Olivier olives are “hand-placed” into their containers, rather than machine thrown, and they command a 50 percent premium. Mercedes-Benz says that “hand-finished laurel wood trim graces the interiors” of the C-class sedan. Belvedere vodka is “handcrafted”—distilled four times following traditions that are five hundred years old—and the bottle is stopped with a cork rather than a screw cap. Panera Bread loaves are baked in-store by master bakers. This artisanal quality allows for variation in the look and feel of the goods. The grain pattern in the Mercedes-Benz laurel trim swirls this way in one car and that way in another. The loaves at Panera Bread have slight variations of shape and color. The artisanal nature of New Luxury goods allows emotionally driven spenders to better express their individuality and personal style.

Yet this is “mass-artisanal” because the basic pattern or process does not change. The sandwiches at Panera Bread are all handmade, as is the bread, but according to a standard and unvarying recipe. (And the sandwich makers wear hygienic gloves to remove the negative connotations of handmade.) The wood inserts of the Mercedes-Benz fit precisely into openings that do not vary in size. As a result, consumers get the predictability they have come to expect and enjoy from the mass-market providers. They also make an emotional connection with the artisan involved in the creation of the product, as they would with Old Luxury goods.

Along with being exclusive, Old Luxury goods also carry a sense of elitism: The goods are meant for only a certain class of people. New Luxury goods, however, avoid class distinctions and are not promoted as elitist. Rather, they generally appeal to a set of values that may be shared by people at many income levels and in many walks of life. The Aveda customer, for example, values all-natural ingredients and simple, almost austere, design. It is this value-driven aspect of New Luxury goods that further encourages rocketing behavior; there is no sense of class confusion when a low-income earner carries a Coach bag or eats at Panera Bread. Conventional middle-market goods, by contrast, are driven by only the most obvious of shared values: convenience and cost.

With this set of attributes, it is impossible to mistake a Rolls-Royce, a 15,000-square-foot mansion, or a $12,000 watch as a New Luxury good, and the successful companies are the ones that make that message clear. A marketing executive at Daimler-Chrysler says that the Mercedes-Benz brand used to foster an Old Luxury image, a brand that was like “a traditional English country club, the stuffy preserve of the elite.” But no longer. Now “we want to make it more like an upmarket health club—still difficult to get into, but more modern and accessible.” That is: limited, but not exclusive. Premium, but not just expensive. A statement of shared values, rather than elitist.

Supply Side Forces That Fuel New Luxury

The New Luxury entrepreneur has been aided in the creation of this new class of goods by a number of powerful business forces.

Changes in the Dynamics of Retailing

Perhaps the most important of these changes is the rise of the specialty retailers—Crate and Barrel, Williams-Sonoma, Restoration Hardware, Victoria’s Secret, and others—that have made New Luxury goods far more available throughout the country. They have achieved remarkable success by offering a limited selection of goods in a limited number of categories at premium prices. Williams-Sonoma has grown revenue 21 percent annually since 1991. Bed Bath & Beyond has achieved 29 percent annual revenue growth. These companies are makers of New Luxury goods, as well as distributors of the goods made by other creators; as much as 60 percent of the stock in these stores are private-label brands. The specialty stores are also important definers of the New Luxury lifestyle—consumers are very aware of the “Pottery Barn look” or the “Williams-Sonoma kitchen.”

The growth of the specialty retailers has had the same polarizing effect on retailing as successful New Luxury goods have had on their categories. Consumers flock to the specialty stores and pay a premium for goods in categories that are meaningful to them, but in other categories, they have increasingly turned to the low-cost mass merchandisers such as Wal-Mart and Costco and the cost-focused category killers such as Kohl’s, Lowe’s, and Circuit City. The traditional department stores, such as Dillard’s, Mays, Sears, Macy’s, and Bloomingdale’s, have found themselves facing death in the middle— unable to match the prices of the mass merchandisers or the emotional engagement of the purveyors of premium goods.

Surprisingly, the big discounters have also become important sellers of New Luxury items in certain categories that can deliver high volume. Costco, for example, stocks a larger selection and sells a larger volume of premium wine than any other retailer. On the shelves at the Costco store on North Clybourn Avenue in Chicago we found more than thirty New Luxury items in stock—including wines, clothing, fashion accessories, watches and jewelry, chocolates, and home goods—selling at substantial discounts to other retail outlets. Costco presents middle-class consumers with an almost irresistible value proposition: highest quality at the lowest price.

And Costco will continue to affect the New Luxury market. The company achieved $38 billion in sales in its 2002 fiscal year. With 412 locations, it achieved average sales per store of $92 million. Costco serves over 19 million members who spend an average $2,000 per year. The company operates with net negative inventory—payables exceed inventory with more than twelve net turns per year. Costco’s revenues have doubled since 1996, and product gross margins averaged 10 percent—the lowest of all major retailers in the world, and a good measure of its efficiency. Costco is continually pushing into new categories: It has become a major supplier of fresh cut flowers, offering locally grown varieties at prices 50 percent to 150 percent lower than regional grocery stores or small florist shops. Next on Costco’s agenda is the “home” category—it plans to offer premium furnishings and accessories in new freestanding facilities of one hundred thousand square feet. Costco’s entry is sure to polarize the home goods category.

The “malling of America” continues, if at a slower pace than during its golden age in the 1970s. The trend now is toward even larger malls, with “shoppertainment” features, including rides and themed events, IMAX theaters, and live performances. The increase in the number of specialty shops, the growth in the size of malls, and the growing sophistication of the American shopper mean that there is a steadily rising demand for New Luxury goods to fill the shelves of America’s 45,000 malls.

Availability of Capital

Despite a sharp drop in the amount of money raised by venture capital funds in the years 2000 through 2002, there is no shortage of investment capital available in the United States, and “had a hard time raising the money” is generally not a complaint we heard from the New Luxury entrepreneurs we spoke with for this book. David Neeleman of JetBlue, for example, raised $130 million from five investors. “No one turned us down,” he said—including George Soros, who invested $54 million in the venture.

Some of the initial financing for New Luxury start-ups comes from the founders, and the rise in income and wealth since 1970 has made more personal funds available for such early investment. Ely Callaway was one of just three initial investors in his company, and he invested $400,000 of his own money in the venture. Jim Koch, founder of The Boston Beer Company, made a $100,000 investment. David Neeleman, of JetBlue, committed $5 million.

But New Luxury start-ups usually require outside investment as well, and they benefited from the increase in venture capital activity in the late 1980s and 1990s. It was in those years that many New Luxury brands and companies were founded or expanded their operations—including Coach, Belvedere, and Viking Range. In 1990, venture capitalists provided just over $3 billion to 1,317 companies. In the year 2000, 4,608 companies benefited from venture capital investment, taking in a total of a little more than $104 billion.

After the bursting of the Internet bubble from 2001 to 2002, there was a decline in the number of investment deals done, but it did not mean that capital had dried up altogether. At the end of 2002, there was a pool of $90 billion in uncommitted capital looking for deals. Investors had been shying away from the technology sectors—including software, biotech, networking, and telecommunications. Their new focus gave an advantage to the more tangible and traditional categories that compose New Luxury, including appliances, apparel, and food and beverage.

Many New Luxury entrepreneurs do not start their companies with the intention of taking them public or selling them. Rather, they are committed to managing and building their businesses for the long haul, and many keep them private for years. Kendall-Jackson (founded in 1982) is private. Bose (1964), Patagonia (1976), Crate and Barrel (1962), Pret A Manger (1986), Sub-Zero (1945), Trek (1976), and Viking Range (1984) are all private companies.

But many New Luxury players do go public, and the last fifteen years of the last century also defined the golden age of the initial public offering (IPO). There were 109 IPOs in 1990, which raised a total of $4.5 billion. In 2000, 380 companies went public, raising $75.8 billion, including New Luxury players Tiffany (IPO in 1987), Callaway Golf (1992), Starbucks (1992), The Boston Beer Company (1995), Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia (1999), Coach (spun off from Sara Lee in 2001), and JetBlue (2002).

Access to Flexible Supply-Chain Networks and Global Resources

The easing of international trade barriers and the emergence of global supply-chain management-services providers have enabled companies of almost every size to take advantage of foreign labor markets and put together and manage complex global networks for sourcing, manufacturing, assembling, and distributing their goods.

The major impetus for overseas manufacturing has long been low cost of labor, but there were associated risks of lower productivity, poor production quality, and high shipping costs. But manufacturers worldwide have been making gains in productivity while improving quality and still keeping labor costs low. China, in particular, has outflanked the traditional contenders—especially the newly industrialized countries of East Asia, including Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore—as the country best able to offer quality production at low cost. This can most easily be seen by the large increase in medium- and high-tech goods made in China and exported around the world.

Nor is it necessary for smaller companies to maintain a presence in the countries where they manufacture, thanks to reductions in the price of global travel and the availability of global information and communication networks. The real cost of international passenger travel declined by more than 50 percent from 1978 to 2001. Low travel costs make it much more affordable for US staff to travel overseas to source and oversee production. For retailers such as Crate and Barrel, this means they can do many more trips in search of new ideas and products. In the past, they would send two or three people on scouting and buying trips to Europe each year. Now they have teams traveling to Europe and Asia seven to ten times each year. The cost of shipping and distribution from overseas markets to the United States has also fallen. The real cost of Asia-to-United States ocean freight declined 28 percent from 1993 to 2001, and the real rate of United States-to-Asia shipping declined even more dramatically—by 54 percent. This makes it cost-effective to ship raw materials, components, and finished goods from around the world.

The development with the most impact on the ability of smaller and emerging companies to manufacture goods abroad is the emergence of facilitators who help create optimal supply-chain networks for their clients. This capability is most utilized by fashion retailers, including Limited Brands; Bed Bath & Beyond; and Gymboree, a retailer of children’s clothing and toys.

Li & Fung, based in Hong Kong, is the largest and most successful of these supply-chain optimizers, with some seven hundred customers in 2000 and total revenues of over $4 billion. Li & Fung puts together for its customers the most effective supply chain, which may include suppliers in several countries. According to Victor Fung, a grandson of the company’s founder, the company breaks up the value chain to get the best capability, cost, and schedule. Li & Fung calls it “dispersed manufacturing,” and it has revolutionized the business of manufacturing in Asia for transnationals and for smaller companies based in the United States.

This “model of borderless manufacturing has become a paradigm for the region,” says Fung in an interview in Harvard Business Review. “Today Asia consists of multiple networks of dispersed manufacturing—high-cost hubs that do the sophisticated planning for regional manufacturing. Bangkok works with the Indochinese peninsula, Taiwan with the Philippines, Seoul with northern China. Dispersed manufacturing is what’s behind the boom in Asia’s trade and investment statistics in the 1990s—companies moving raw materials and semifinished parts around Asia. But the region is still very dependent on the ultimate sources of demand, which are in North America and Western Europe. They start the whole cycle going.”

The Li & Fung model has enabled fashion retailers to become designers, not just stockists. “Retailers are now participating in the design process,” says Fung. “They’re now managing suppliers through us and are even reaching down to their suppliers’ suppliers. Eventually that translates into much better management of inventories and lower markdowns in the stores.”

For New Luxury companies in many categories, the dispersed manufacturing model enables them to take advantage of capabilities available only in Asia, shorten the buying cycle, and reduce costs. Pleasant Company, maker of American Girl dolls, for example, buys its famous “sleepy eye” from a factory in China because it makes the very best eyeball in the world, according to president Ellen Brothers. “The way they’re put together, the material that we use, the actual hair that makes up the eyelashes. It’s a more authentic eyeball.” It is a technical difference that delivers an emotional benefit—the doll looks more real and feels more like a genuine character who can become a friend.

Focus on Speed and the Collapse of the Innovation Cascade

Another important factor in the spread of New Luxury—and closely related to the changes in the retail environment—is the collapse of the innovation cascade. New Luxury goods are more responsive to trends than are conventional goods, and they flow in a faster stream of innovation. It takes much less time for a new style, design, feature, technology, or material to cascade from the high-end item, where innovations generally appear first, to the middle-market good. The trend has affected every category. In cars, for example, it used to take several model years for a new technology to cascade from the high-end to the mid-range models. Power door locks, for example, were introduced in the 1956 Packard. By 1970 only 6 percent of all U.S. car models came with power door locks as standard equipment and penetration reached 80 percent as late as 1990— more than twenty years for a desirable and relatively inexpensive feature to cascade to the majority of middle-market models.

Affluent consumers—especially the top 5 percent of earners— have been instrumental in accelerating the cascade, because they constantly push the upper limits of the categories in which they consume, in both price and innovation. In cars, for example, the most affluent consumers have pushed Mercedes-Benz and BMW to extend the price range of their models over $150,000, creating technology and innovation that will eventually (but in increasingly shorter time periods) cascade to the middle market.

The innovation cascade has been easiest to see in the world of fashion, where haute couture designers reveal their new clothing ideas in the European shows, and the producers of middle-market clothing interpret the concepts into lower-priced, practical street wear. Traditionally, the translation of the innovations in a $2,000 custom-made style into a $100 outfit could take a couple of years. Now it gets done in a few months, or even a few weeks. For example, Prada introduced a new material—ostrich leather—at the European runway shows in September 1999 and featured a $2,800 ostrich leather skirt in its spring 2000 couture collection. But the middle-market consumer did not have to wait two years to join in the ostrich leather excitement. Designer Bebe had a $78 ostrich leather handbag ready for spring 2000, and Victoria’s Secret previewed an ostrich-embossed leather skirt in the fall of 2000.

A key influence in the collapse of the fashion cascade has come from a small number of large retailers, who have sought to shorten fashion cycles and avoid the retailer’s worst nightmare: unsalable inventory. Zara, a clothing retailer that is based in Spain and has more than five hundred stores worldwide, has been particularly successful in changing the rules of the fashion game. The industry standard lead time—the time it takes from the initial design of a new article of clothing to the moment it gets hung on a rack or stacked on a shelf—is about nine months. At Zara, the process can take as little as three weeks.

Zara is not driven particularly by the haute couture runway shows, nor does the company concentrate all activity around the traditional fashion “seasons”—fall-winter, spring-summer. Rather, Zara seeks to stay close to the market, watching for what’s selling best and new trends that are emerging, and responds to them quickly. It does this by creating and maintaining a close connection between the store managers and a team of more than two hundred designers who work at the headquarters in La Coruña, Spain. When a store manager notices that a particular style is moving briskly, for example, she can order more units via a customized handheld device. The order is placed immediately and sent to one of Zara’s factories, most of which are in Spain. Factory deliveries are made twice each week, resulting in about eleven inventory turns per year, two to three times the industry average. Any store manager may also make a suggestion for a modification to an existing style or propose an entirely new article or design. The designers at headquarters collect and evaluate the suggestions as they arrive, produce designs on their computers, and, when finalized, send them over the company intranet to a factory. The result is that Zara designs and produces as many as ten thousand new items every year. Although its manufacturing costs run some 20 percent higher than its competitors’, Zara rarely needs to write off unsalable inventory. Profits of Zara’s parent, Inditex, increased 31 percent in 2001. Zara’s founder, Amancio Ortega, is the richest man in Spain.

Zara’s example is provoking other retailers to respond. ASDA, a giant UK retailer owned by Wal-Mart, has followed Zara’s lead, creating what it calls “fast fashion”—it can get new styles into stores in seven weeks and bring in new styles once a month. In the United States, too, Wal-Mart has embraced the idea of fast-moving New Luxury goods. The monster retailer sells some $25 billion in clothes and accessories each year and has expanded far beyond the blue jeans, underwear, and kids’ clothing it is known for. In 2002, New York Times fashion writer Cathy Horyn wrote about her fondness for Wal-Mart clothing. She describes wearing a pair of sandals to a Balenciaga runway show in Paris. There she bumped into Allen Questrom, then CEO of Barney’s New York, a retailer, who noticed the sandals and asked, “Are those Gucci?” “No,” Horyn replied. “Wal-Mart.”

We’ve seen the collapse of the innovation cascade across New Luxury categories—a constant flow of new styles, new ideas, new features, and new materials. In food and beverage, Starbucks regularly offers new drink concoctions and features new coffee-bean types. Panera Bread offers daily specials in its cafés, lunches featuring seasonal ingredients, and a dozen varieties of freshly baked bread, from sourdough to tomato basil, in a variety of forms including baguettes, rolls, and “bowls.”

Flexibility and Speed of Manufacture

New Luxury goods often present special challenges in production. It’s one thing to produce a high-quality wine, for example, in a volume of a few hundred cases per year. It’s another thing to produce the same wine in a volume a hundred times as high, and have the taste, color, and nose remain consistent and worthy of the premium price.

New Luxury companies generally start producing their goods in low volume and plan for modest growth. But their success can be far more rapid than they expect, requiring them to scale up production faster than anticipated and forcing them to find ways to maintain their product standards at much higher quantities. This is what happened to Jim Koch of The Boston Beer Company. He hoped to sell eight thousand barrels of beer annually within five years of starting the company. Instead, he reached his goal in the first four months of production, and the company proceeded to grow at 30 percent a year. Koch could not make that much beer in his own small handcraft brewery. The solution was to control the selection of the ingredients, specify all aspects of the brewing process—which combined aspects of nineteenth-century brewing with twentieth-century quality-control methods—then outsource it and, finally, manage distribution. By choosing to control the key elements of the process without building its own breweries, Boston Beer was able to grow to 1.2 million barrels in sales by 2001 and maintain a reputation for beer that is artisanal—containing elements of handcraft—but available in far larger volumes than handmade microbrews.

Many New Luxury products contain important technical features that differentiate them from their competitors and require complex and expensive manufacturing processes. Callaway Golf, for example, uses a variety of metals in its clubs, including titanium, stainless steel, carbon steel, tungsten, and graphite, along with specialty adhesives, paints, and solvents. The ability to work with these metals, often in combination, to extremely exacting specifications is a key to the Callaway technical difference. The company subcontracts the production of certain components, such as titanium heads, to shops that specialize in what is known as “investment casting.” This lost-wax molding process is very flexible and cost-effective and also has the precise dimensional control necessary to produce the close tolerances Callaway requires. Callaway does final assembly of the outsourced components—the head, shaft, and grip—in its own 80,000-square-foot production operation in Carlsbad, California. There it also customizes the length of the shaft and the angle of the club to create some 17,000 variants to suit different types of golfers with different types of swings—another example of mass-artisanal manufacture.

New Luxury Is More Than Marketing

New Luxury goods cannot be imagined, developed, manufactured, distributed, or marketed following conventional middle-market business attitudes or practices—although many businesses assume they can be.

New Luxury companies such as Coach, BMW, Panera Bread, Millennium Import, Callaway, and Kendall-Jackson are careful to keep their brand names closely connected to the product itself and to the emotional drives of their consumers. Although the brand name is of tremendous importance, it is rarely promoted without a connection to a specific product or product attribute, or to the story of the leader or company that created it. Absolut vodka, by contrast, built its brand on what became a famous advertising campaign: brilliant visual interpretations of the bottle shape. But Absolut is now little more than its famous brand name; the vodka itself has become the standard pouring brand at many bars. Belvedere and Grey Goose, in contrast, the leading premium vodkas, connect their names to specific attributes of taste, distilling techniques, country of origin, awards, and bottle innovations.

Some companies hope to create a New Luxury product by sprucing up an existing product, adding new features, redesigning, or repositioning through advertising. This is the approach that American carmakers have often taken in creating “luxury” models— they use the platform of a midrange model, equip it with the most powerful engine available, fit it with leather seats and other niceties in the cabin, and make it available in special paint options. The most notorious example is the Cadillac Cimarron, introduced in 1982, which was little more than a Chevy Cavalier with fancy trim; but there are many others, including “near-luxury” models from Oldsmobile, Buick, and Mercury. New Luxury consumers are not fooled by these superficial “new and improved” products. They seek genuine benefits and real differences.

Companies sometimes assume that the New Luxury consumer will be seduced by a high price point, but New Luxury consumers do not automatically assume that if it costs more, it must be better. They are sophisticated enough to evaluate the technical and functional benefits of a product and to trust their own emotional reactions to it. We heard over and over again from consumers that the most expensive entry in a category is not always the best. As one consumer put it, “Luxury can sometimes mean better quality and last longer, but sometimes it’s cheap and flimsy.”

New Luxury is much more than a marketing exercise, although marketing is, of course, a key part of the process. But New Luxury goods are not created solely in the marketing. They are created through all the management disciplines—and often through unconventional marketing methods, as we’ll see in the chapters devoted to specific brand stories.

The Practices of New Luxury Leaders

New Luxury leaders and their companies follow a set of management practices that are different from those of conventional or Old Luxury goods creators. Using them, New Luxury companies have shattered conventional beliefs in nearly all aspects of product creation and distribution, including ideas about price ceilings, price ranges, brand extendibility, consumer sophistication, market stability, and the innovation cascade.

1.

Never underestimate the customer. In every New Luxury category, consumers are more affluent, better educated, and more sophisticated than ever before. In the categories they care about, they consider themselves to be knowledgeable and even expert. These consumers appreciate traditional quality, technological innovation, and emotional authenticity. They care about the heritage of a brand and are interested in the category as a whole.

This knowledge, taste, and discernment can be seen in many New Luxury categories. Robert Mondavi and Jess Jackson challenged the long-held assumption that the palate of the American consumer was unsophisticated and undiscerning. They believed that Americans could appreciate the more complex flavors and subtle aromas of premium wine, and they built substantial businesses around that belief. In fact, they discovered that Americans had such pronounced ideas about taste that they have helped to change the flavor of wine worldwide.

Consumers also have a sensitive built-in calculator that enables them to assess goods and determine whether the price is aligned with the value and how the cost fits into their entire structure of emotional needs and purchasing power. They will make a purchase at a price point that their calculator tells them is too high only if that product delivers very potent rational and emotional benefits. They will also make a purchase when the price-value calculator tells them that the price point is very low and that they are getting a bargain.

2.

Shatter the price-volume demand curve; seek higher price points and higher volumes. The masstige segment, for example, is 20 to 40 percent of many personal-care categories and growing at twice the industry average. Sub-Zero shattered the conventional wisdom that there was no substantial household-appliance market above the $1,000 price point. BMW is the most profitable car company in the world, with unit volume of its New Luxury models ten times that of superluxury cars.

New Luxury companies can also maintain their position off the traditional demand curve even as they achieve high growth. Williams-Sonoma substantially increased revenues and profits in 2002 over the previous year. BMW continues to grow unit sales while maintaining prices, as do Panera Bread and Victoria’s Secret. Jess Jackson redrew the demand curve for the wine industry. He saw the potential to create a new segment in the market where higher prices and higher volume would intersect for substantially higher profits.

3.

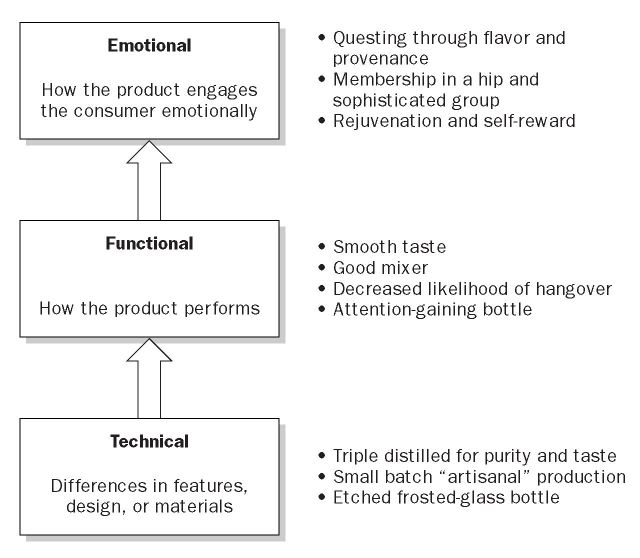

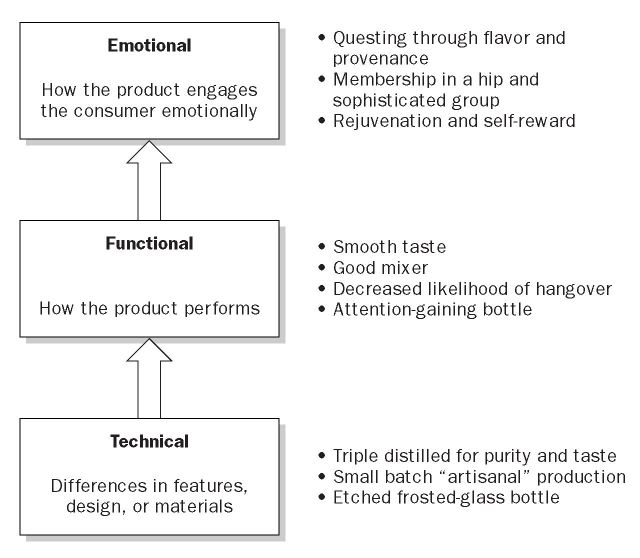

Create a ladder of genuine benefits. Perhaps the most important of the New Luxury practices is ensuring that the products deliver a ladder of genuine differences—technical, functional, and emotional.

The products must first succeed on a technical level, with genuine competitive differences in materials, workmanship, or technologies. Panera Bread’s six-dollar sandwich, for example, offers bread baked on the premises, with locally grown lettuce and seasonal ingredients, which are genuinely different and perceptibly fresher than the mass-produced buns and character-free iceberg

Premium vodka provides a ladder of benefits.

shreds of the standard fast-food restaurant. Callaway Golf ’s original Big Bertha driver featured a head 50-percent larger than that of a conventional driver, but no heavier.

The next rung on the ladder is functional performance. The technical differences must translate into genuine differences in performance. The larger head of the Big Bertha driver makes it easier for the golfer to hit the ball farther. The traditional recipe and four distillations of Belvedere vodka make for what Belvedere claims is a “distinctive creamy smoothness, an aromatic nose, and a semisweet lingering finish.” This is not a meaningless marketing claim, however; vodka consumers profess to appreciate subtle differences in taste and drinking style. As one vodka aficionado explained to us, “Absolut is heavier in consistency, and it definitely gets you drunk faster. Belvedere is very smooth, and it does not have this hammered-after-a-few-drinks effect like Smirnoff or Stoli. Grey Goose has a funny aftertaste to it.”

The final rung on the ladder of differences is the emotional one. For the emotionally driven spender, the greatest benefit comes from how powerfully the product connects with his needs. To find a powerful positioning, New Luxury innovators must understand the consumer’s behavior, needs, and unspoken (sometimes even to himself ) desires. They must also offer distinctive functional advantages that are specifically tied to the targeted emotions, as well as a technical platform that lends credibility and authenticity to the functional claims.

If the product delivers the ladder of benefits, consumers will make a connection between the technical and functional benefits and become emotionally engaged with the brand. Pet lovers, for example, buy gourmet pet food such as Nutro because it is technically different, offering added nutrients and organic ingredients. They believe that the technical differences create superior product performance—they produce, as promised, a shinier coat or a calmer disposition. Consumers find these performance differences emotionally meaningful because it seems that the product is enabling them to be more nurturing and loving. The premium and superpremium pet-food segments are growing at a 9 percent compound annual growth rate, in comparison to 1 to 2 percent for conventional products, and they now account for almost one-third of the total pet-food market.

A word of caution: traditional market research will often miss the emotional underpinnings of New Luxury success, and conventional product testing may undermine the linkages between the emotional, functional, and technical benefit layers. To generate insight, innovative players typically spend more time in the market and conduct one-on-one interviews with their core customers—in their homes, at retail sites, in their domains.

4.

Escalate innovation, elevate quality, deliver a flawless experience. The market for New Luxury is rich in opportunity, but it is also unstable. This is because technical and functional advantages are increasingly short-lived, as new competitors enter the market, and because of the relentless downward pressure of the innovation cascade. What was luxurious and different today becomes the standard brand of tomorrow. A well-established brand can’t maintain an emotional position for long if the technical and functional benefits become undifferentiated.

Winners in New Luxury markets aggressively and continuously up the ante on innovation and quality, and they render their own products obsolete before a new competitor does it for (or to) them. They strive to shorten the product development cycle, make substantial investments in manufacturing improvements, and do not slavishly follow the rule that research and development should equal 5 percent (or any other fixed percentage) of sales.

5.

Extend the price range and positioning of the brand. Many New Luxury brands extend the brand upmarket to create aspirational appeal and down-market to make it more accessible and more competitive and to build demand. A traditional competitor’s highest price may be three to four times its lowest; New Luxury players often have a fivefold to tenfold difference between their highest and lowest price points. They are careful, however, to create, define, and maintain a distinct character and meaning for each product at every level, as well as to articulate the brand essence all the products share. The Mercedes-Benz range, for example, extends from the successful C230 sports coupe at $26,000 to the Maybach 62 at $350,000, a thirteenfold span. Every Mercedes-Benz model shares the brand themes of advanced engineering, quality manufacture, flawless performance, solidity and safety, luxurious comfort, and the distinctive Mercedes-Benz look and badging—but each one interprets those themes in its own characteristic and genuine way.

Boston Beer sells its superpremium product, Samuel Adams Utopias, for $100 a bottle. The company makes only 6,000 bottles per year and, according to founder Jim Koch, sells out the entire stock in a week. The lesson of Utopias, says Koch, is that “there is always a higher end.”

6. Customize your value chain to deliver on the benefit ladder. New Luxury creators often work outside the established value chain in order to overcome the structural barriers that stand in the way of small producers. They put the emphasis on control, rather than ownership, of the value chain and become masters at orchestrating it. Panera Bread mixes all the dough for its signature sourdough bread at a central commissary to ensure that the quality and taste never vary. Callaway Golf assembles its outsourced components in its own facility to ensure that the “swing” is right. Jess Jackson built a disproportionately large sales team to ensure that the retailers— who were used to buying standard brands from big wholesalers— understood the Kendall-Jackson “fighting varietal” story.

7.

Use influence marketing; seed your success through brand apostles. In New Luxury goods, a small percentage of category consumers contribute the dominant share of value. In categories with frequent repeat purchases, such as lingerie and spirits, the top 10 percent of customers generate up to half of category sales and profits. Reaching those important consumers requires a different kind of launch, involving carefully managed initial sales to specific groups in specific venues, frequent feedback from early purchasers, and word-of-mouth recommendations. Belvedere vodka, for example, was launched through tasting events for bartenders, and gift bottles were sent to cultural influencers in important markets.

Such consumers are often highly influenced by well-known advocates they admire. Jess Jackson enlisted key influencers to create a buzz for his wines. When introducing the Big Bertha driver, Ely Callaway understood that recreational golfers—many of whom are businesspeople—would be influenced by who was using the new and unusual clubs. He enlisted Jack Welch, the most celebrated CEO golfer at the time, not only to use the clubs but also to invest in his company, and he persuaded Bill Gates to appear in ads. Red Bull, a premium-priced “energy” drink, has built a $100 million business by focusing on the social environments of its core customers: health clubs, bars, and hip hangouts.

An intense, continuing focus on these core customers will yield early signs of a shifting market and ideas for next-generation variants, features, or products.

8. Don’t rest on your laurels; continually attack the category like an outsider. New Luxury creators look beyond their own categories for the trends and patterns that will generate the next breakthrough. Sources of inspiration can include Old Luxury products or services, innovations from Europe or Asia, analogues from other categories, and advice from experts and professionals. It was on a worldwide scouting expedition that Edward Phillips came across the vodka that became the prototype for the Belvedere brand. When the makers of Freschetta pizza sought to overtake Kraft Foods’ DiGiorno in the premium frozen-pizza segment, they assembled a panel of five gourmet chefs from the best restaurants in the United States. The chefs, in turn, worked closely with some of the best cooking schools in Italy to develop a superior sauce and crust.

People within New Luxury organizations don’t think like employees of conventional producers, and that is often because they are driven by the original outsider thinking of their founders. Ellen Brothers, president of Pleasant Company, maker of American Girls, says that the thinking of founder Pleasant Rowland still infuses the company. “If you ask any of our twelve hundred employees what business we are in,” says Brothers, “no one will say ‘the toy business.’ Every one of them will say, ‘We’re in the girl business.’ ”

The challenge for the New Luxury creator is that when she becomes successful, her outsider thinking becomes the new conventional wisdom, and competitors flood the market hoping to capitalize on it. The Napa Valley is home to many small producers who hope to follow the Robert Mondavi and Jess Jackson model but who don’t have the personal vision or the commitment or the understanding of the New Luxury practices.

As a result, New Luxury creators must force themselves to think like outsiders all over again.