Ten

Only the Best for Members of the Family: American Girl, Pet Food

The 1950s American family—composed of mom, dad, and two kids—is now almost an anomaly (only 24 percent of adult Americans are married and have children living at home), but that does not mean that consumers do not care about family or don’t want to strengthen connections among family members. It’s just that they are redefining what the family is and how they go about Connecting.

As we’ve seen, today’s families have fewer kids and the parents have less time to spend with them, so they sometimes turn to premium goods to enrich their time together. Twenty percent of the respondents to our survey said they spend on goods that “make them feel like a good parent.” In many single, nonfamily households, of which there are 35 million, pets have become the new children. There are 136 million dogs and cats in the United States, compared to 48 million children under the age of twelve—and the pet owners, both single and married, lavish attention, and premium goods, on them as if they were their kids.

Kids and pets are important drivers and recipients of New Luxury spending; the role of American children is particularly interesting because they are sophisticated consumers in their own right. They are exposed—often more exposed than even their parents are—to the marketing messages contained in every form of media. Kids in their “tweens” (ten to twelve) and early to mid teens (thirteen to seventeen) are particularly savvy about the messages and meanings of certain categories of goods. As they make the transition from childhood to being full-fledged members of society, they become concerned about self-branding and aligning themselves with people and things they deem to be “cool” and of value.

American kids also have more disposable income of their own. They are spenders in ways that their parents and grandparents were not. Younger teens, especially, are willing to put most, if not all, of their cash into goods that they believe will improve their looks and heighten their status with other kids. As one eighteen-year-old put it, “Ninth- and tenth-graders—that’s where the money is.”

Today’s kids have a very different view of material needs than do their parents or grandparents. The many activities of the “overprogrammed” American child often require specialized goods, and the children—often far more than their parents—are eager to gain status through their possessions. School clothing, sports equipment, stereo gear, CDs, televisions, computers, phones, furniture, travel, health care, medicines, gourmet foods, food supplements, dentistry, and cosmetic surgery—kids are major consumers in many New Luxury categories. It is not unusual for young American consumers to have their own phones, electronics, and premium sports equipment, and to have traveled widely during school vacations.

American children also have significant influence over many of the purchases made in the household, from the clothing dad wears, to the car mom buys, to the food the family eats, to the destination of the next family vacation. In some cases, it is the kids who will catalyze the parents’ trading up. They prefer to go out for a family lunch at Panera Bread or Chipotle rather than Burger King. The next generation of consumers is sure to be even more discriminating and demanding purchasers of New Luxury goods and to trade up even further.

The Girl Business

We have seen that women are important New Luxury consumers; girls are, too—and girls, aged seven to twelve, are a special group. They are old enough to be readers and learners but still young enough to be strongly influenced by their families and their peers. They are educated enough to be interested in history and society, but still young enough to enjoy playing with dolls. And unlike girls of earlier generations, they are surrounded by messages that encourage them to be strong young women and succeed in whatever endeavor they choose. But they are also bombarded with messages from the popular culture about the excitements of being cool, dating, competing, and winning. Barbie, the biggest-selling doll in the world, is all about dressing up, going out with boys, and being a hip teenager.

But Pleasant Rowland, creator of American Girl dolls, believed there were many young girls who were in no particular hurry to grow up and start competing and plenty of mothers and fathers who felt the same way. These girls, she believed, were still more interested in dolls than in boys, and they wanted dolls that looked like they did—like girls.

The result of Rowland’s conviction has been the emergence of American Girl: a $370 million brand of premium dolls that has sold 7 million dolls since 1986 and 82 million books (not one of which features a first-romance plot) and claims 650,000 subscribers to its magazine. At $84 each, the dolls are more than $60 pricier than a typical Barbie. And while most other tween brands are driven by short-term trends, American Girl has introduced only five new dolls to its core American Girl Collection line since 1986.

What’s more, over 80 percent of the brand’s sales are direct-to-customer sales, meaning that while the creation of higher quality and greater original content may entail higher cost, American Girl is able to capture more of the value than competitors who sell through nonproprietary retail channels.

Many of our trading-up stories begin with a founder’s vision, and Pleasant Rowland’s is one of the most vivid of all. In the fall of 1984, Rowland, then forty-four, accompanied her husband to Colonial Williamsburg for what she thought would be a vacation. “Instead,” she told FSB magazine, “it turned into one of the seminal experiences of my life.” As a teacher and history buff, she loved everything about Williamsburg—the sense of the past, the costumes, the homes, the accessories. She described “reflecting on what a poor job schools do of teaching history, and how sad it was that more kids couldn’t visit this fabulous classroom of living history. Was there some way I could bring history alive for them, the way Williamsburg had for me?”

The “way” became clear to her the following Christmas, when she went shopping for gifts for her two nieces, then eight and ten years old. It was the year of the Cabbage Patch Kids, which Rowland found ugly; she was similarly unimpressed by Barbie. “Here I was,” she told FSB, “in a generation of women at the forefront of redefining women’s roles, and yet our daughters were playing with dolls that celebrated being a teen queen or a mommy. I knew I couldn’t be the only woman in America who was unhappy with these Christmas choices.” Then a vision “literally exploded in my brain.” She imagined “a series of books about nine-year-old girls growing up in different times in history, with a doll for each of the characters with historically accurate clothes and accessories with which the girls could play out the stories.”

Like many other New Luxury founders, including Ely Callaway, Jim Koch, and Jess Jackson, Pleasant Rowland funded her idea largely with her own money. She had saved some $1.2 million from textbook royalties and decided that she would risk $1 million of it on her idea.

In a single weekend, she developed the first three characters— Kirsten, Samantha, and Molly—their clothing, and the stories that would surround them. They would all be bright and interesting girls, each living in a different time period and with a detailed personal story. Samantha Parkington, one of those first dolls, is still the most popular. She is, according to the Web site description, “a bright, compassionate girl living with her wealthy grandmother in 1904. It’s an exciting time of change in America, and Samantha’s world is filled with frills and finery, parties and play. But Samantha sees that times are not good for everybody. That’s why she tries to make a difference in the life of her friend Nellie, a servant girl whose life is nothing like Samantha’s!”

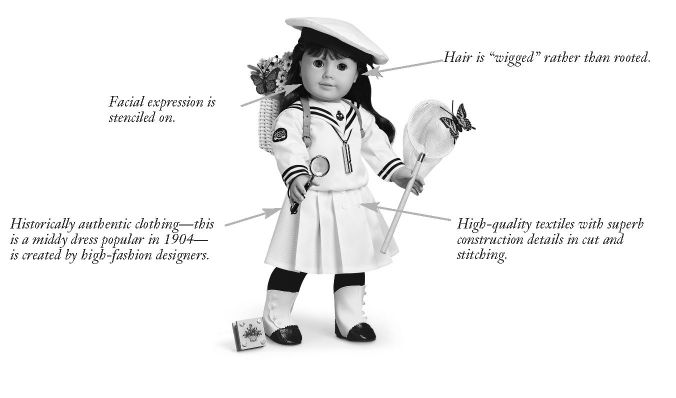

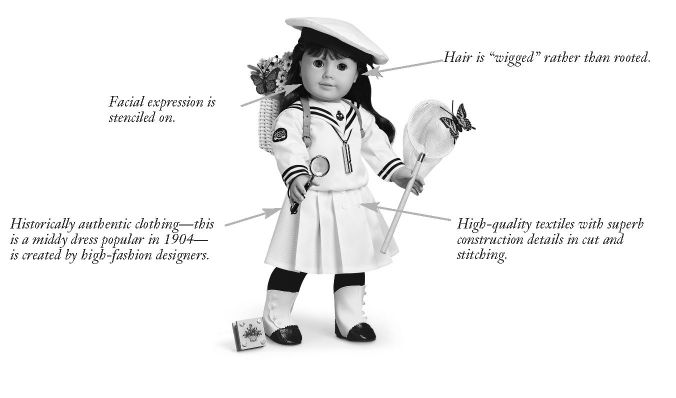

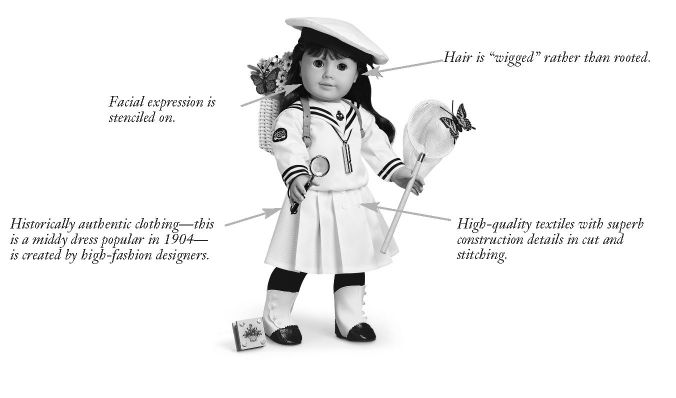

American Girl dolls have genuine differences in design and construction that translate into long-lasting performance and emotional engagement spanning generations.

Photo of Samantha courtesy of the Pleasant Company.

Rowland had no experience in doll making, but knew she wanted a very different product from the conventional molded-plastic dolls that flooded the mass market at the time—and still do today. She wanted to create quality figures with a lot of character that would have expressive faces and beautiful clothing and would last through many hours of play—she did not mean these dolls to be placed in display cabinets or kept on the shelf. She located a doll maker in Germany who could turn her vision into a reality, and—as many other New Luxury leaders have done—outsourced all the production of her dolls to him. The accessories were outsourced to a manufacturer in China.

Rowland then turned to the marketing channel. She knew that Samantha would be unable to compete with Barbie on the shelves of mass-market toy retailers such as Toys “R” Us. The American Girl offices were not far from Lands’ End, a direct-mail clothing retailer, and she decided to apply its strategy to her product by reaching out to girls through direct mail. In the fall of 1986, Rowland sent out five hundred thousand catalogs—far more than her direct-mail contractor advised her to send. From September 1 through December 31, 1986, the company sold $1.7 million of American Girl dolls— the first $1 million of revenue coming in the first three months of business. Within four years, American Girl had grown to $77 million in sales, and it grew to $300 million in the five years following.

In 1998 in Chicago, American Girl Place was opened—a retail and entertainment environment that includes a theater and an original musical revue, a café, shops, a bookstore, and a variety of events and programs designed to bring the dolls and their stories even more alive for the visitors. It has become the highest-performing retail store on Michigan Avenue, Chicago’s main shopping thorough-fare, and it generates $40 million in revenue each year.

Girls go to American Girl Place for “fun and fancy dining.” Birthday parties include three-course lunches featuring “Savory Toast Points,” “Tic-Tac-Toe Pizza,” “Frittata Quiche,” and “Chocolate Pudding Flower Pot.” In addition to lunch, there’s Circle of Friends: An American Girl Musical. And there are after-school teas, cooking classes, book signings, and the American Girl photo studio, where any child’s picture can be placed on a souvenir copy of American Girl magazine.

The store has become a mecca for little girls, attracting more than 1 million visitors per year. Young girls beg their parents to take them to the Chicago store in much the same way that others yearn for Walt Disney World. We visited American Girl Place with Alison, the eight-year-old daughter of a close friend, and during our visit she told us about her favorite doll, Samantha Parkington. “I love Samantha,” Alison said. “She is my friend. I know where she grew up and that she made it through tough times. I love to dress her and care for her. I even have clothes that match hers, so that we can dress alike.” By the end of the visit, we had succeeded in spending $300—for a doll, two extra outfits, one matching outfit for Alison, two Samantha books, and a photo of Alison reproduced on the cover of American Girl magazine.

In 1998, her dream realized, Pleasant Rowland sold her company to Mattel, makers of Barbie, one of the catalysts of her original vision. Many observers found the sale ironic, but Rowland felt a “genuine connection with Jill Barad”—who was then CEO—“the woman who had built Barbie.” She saw in Barad a woman not unlike herself: a “blend of passion, perfectionism, and perseverance with real business savvy. During the same thirteen-year period that I built American Girl from zero to $300 million, Jill built Barbie from $200 million to $2 billion.” Ellen Brothers, current president of Pleasant Company, maker of American Girl dolls, continues the girl business that Rowland created. “It is not products we’re selling,” Brothers told us. “It is stories. It is incredibly powerful. The daughter aspires for the dolls, and the mother endorses them.”

The dolls succeed on all three levels of the benefit ladder. First, they offer genuine technical differences in design, features, and methods of manufacture. Alison’s mother quickly ticked off the distinctions of an American Girl doll: “They have wonderful hair, sewn seams and real buttons, shoes that tie, outfits that are authentic to the historical period, and bodies that are anatomically correct and realistic.”

The hair is a particularly important characteristic of American Girl dolls. “Most dolls in the world today have rooted hair,” Ellen Brothers told us. “Rooted hair is the kind you sew on a sewing machine, and it is very cheap to get that done in the factories of the world. You pick up a doll and pull back the hair and you can see the little dots. You’ll see the sewing marks. From day one, Pleasant said, ‘I’m going to have wigged hair.’ This hair is much more expensive to manufacture, but it is the difference between night and day.”

The American Girl books are as carefully created as the dolls themselves. They are produced in China, elaborate and in full color, with extensive illustrations, photographs, and special features. Samantha’s Ocean Liner Adventure, for example, tells the story of Samantha’s trip to Europe aboard the SS Londonia, and includes reproductions of many of the items Samantha might have enjoyed on her journey, such as the dinner menu in first class, a dance card, a game, and a luggage tag. Lots of information is contained in a charming story.

The package of beautiful dolls and rich books delivers functional differences in how girls play with the dolls. Clarissa, a seventeen-year-old, remembers playing with the dolls when she was about nine. “My friend and I made story lines based on the essential character of each doll, but we brought them into the present day, though sometimes they traveled in time to visit each other. I remember fondly starting a story in my friend’s room and ending it somewhere in the far corner of her yard. The assorted outfits and accessories traveled with us; we couldn’t let Samantha meet her friends for the evening in her morning outfit!”

Alison discovered an important functional difference in American Girl dolls when her brother threw Samantha out the window, causing an amputation. Alison’s mother called the company and was told to send the doll to their “hospital,” where she would receive “treatment” from an American Girl “doctor.” Samantha was returned home, good as new, with a patient’s bracelet around her wrist. Alison cried at the sight of her. “We can offer a 100-percent guarantee on our dolls,” says Ellen Brothers. American Girl magazine is a critical link between company and consumer. The magazine provides a sounding board for problems the girls are facing. One writes, “My parents recently told us that they are getting a divorce. I’m really scared. Nothing helps.” Another adds, “Both of my best friends are moving. I never had a best friend move before, and I don’t think I can handle it. I cry just thinking about it! What should I do?” “Thank you for your wonderful magazine. I can’t keep my eyes off of it. When I grow up, I want to help American girls make their dreams come true. Just like you do for me,” another girl writes. An older girl adds, “You really do celebrate girls yesterday and today. You’ve changed my life with my mother. Every time I received an issue, our bond between mother and daughter became closer.” Most important—as with all New Luxury goods—is the strong emotional connection that girls (and their mothers) make with the dolls. “Our market research says there is so much emotion wrapped up in these characters,” Brothers told us, “that moms want to hand them down to their daughters. They’re not put away on a shelf. As soon as I have a daughter, I want it to be hers. That’s different from the collector’s mentality. They don’t want to open the box, because it’s worth ten times more on eBay with the original box and packaging. That’s a Barbie phenomenon, but it’s not the American Girl phenomenon.”

Much of the emotional appeal, especially to parents and grandparents, stems from the expression of values. The American Girl dolls are about civility, generosity, caring, respect for diversity, and ambition. Josefina, a Hispanic girl living in New Mexico circa 1824, hopes to be a healer. Addy, an African American girl, escapes from slavery in 1864 and learns the true meaning of freedom. Kaya, a Nez Percé Indian of 1764, shares stories with her blind sister and hopes to become a leader of her people one day. The dolls may play to classic themes, but they are not presented as stereotypes. Brothers says that they believe in the “authentic replication of anything of a historical nature.” Kaya’s moccasins, for example, have a little flap on the back just as traditional Nez Percé moccasins do. “One of the tribal members said to us, ‘Wow! How did you know to do that?’ ”

For American Girl consumers, the dolls touch on three emotional spaces. They are, when playing alone, a form of Taking Care of Me—moments of quiet play and exercising of the imagination. They are also a key form of Connecting, as Clarissa attests. The dolls enable girls to connect with each other through stories and characters and to connect with their parents, especially mothers. Finally, little girls do a lot of Questing through their dolls—learning about historic times and exotic places and creating scenes and stories in which they are vicariously the heroines.

As Alison’s mother told us, “I found out about American Girl from another mother. Now I’m telling all of my friends that there’s a doll available that comes with a history lesson. If you want your child to read, and if you want your child to have perspective on her place in the world, then get her an American Girl doll and the books that go with it.” That’s word-of-mother marketing.

The American Girl vision is clear: provide girls with a wholesome, inviting way to learn through fantasy about everyday heroes and give them role models that survive and prosper under difficult conditions with respect, kindness, and appreciation. As a business, American Girl commands premium prices and earns extraordinary brand loyalty. It offers customers a continuous stream of new products supported with extensions that build on the original product idea.

“We’re in entertainment and education,” says Brothers. “It’s about empowerment. It’s about being the best you can be. Every character has a different passion, and there’s always a moral. A lot of emotion is wrapped up in these dolls, and they become heirlooms.” Even as part of Mattel, the outsider thinking of founder Pleasant Rowland has continued. “If you ask any of our twelve hundred employees what business we are in,” says Brothers, “no one will say ‘the toy business.’ Every one of them will say, ‘We’re in the girl business.’”

Pets and Their People

Mothers of girl children are no more indulgent of their daughters than are owners of beloved pets. Mona, a twenty-seven-year-old single professional, had been considering adopting a cat for some time. She lives alone in a studio apartment in a city, and although she’s in a long-term relationship, her boyfriend works in a different city, so Mona spends her nights alone more often than she would like. Still, she wasn’t sure she wanted to take on the responsibility of caring for a pet, nor did she think it was fair to make a pet spend long hours alone during the day.

But after September 11, she took the plunge and adopted Chloe, a five-year-old tortoiseshell that is, she told us, “the most beautiful kitty in the world.” Mona cites two reasons for bringing Chloe into her life. “First, and I know this sounds melodramatic,” she said, “if there is a catastrophe here like there was in New York, I don’t want to die alone. I’d feel much better if Chloe was with me. Second, I really felt the need for more companionship post-September 11. There’s only so much solace you can get from talking with your boyfriend long distance. And seeing colleagues during the day or friends in the evening is not the same as having a fuzzy fellow creature living with you and hanging out on the bed with you watching television.”

Soon enough, Chloe had become not only a fixture in Mona’s life but also a major focus of spending. “She will eat nothing but premium Iams cat food,” says Mona. “I often get her special kitty treats from the Three Dog Bakery around the corner. And I bought her a $120 pet carriage so when we stroll to the vet for a checkup she doesn’t have to be confined in one of those tiny, cramped carriers. Spoiled enough?”

Americans love pets—62 percent of America’s 105 million households are home to a pet. In addition to the 136 million dogs and cats sharing their lives with us, there are untold numbers of other creatures, including such exotic companions as fish, birds, turtles, frogs, geckos, rabbits, iguanas, chinchillas, hamsters, gerbils, rats, squirrels, opossums, snakes, prairie dogs, and an increasingly popular type of lizard known as a skink.

Although the pet population has remained fairly stable over the past decade, growing in size at a modest 1 to 2 percent annually, spending on pets has grown at a much faster rate—a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 8 percent. Nearly half of all pet spending is on food; not surprisingly, the premium and superpremium brands—including Diamond Pet Foods, Eagle Pack, and Bil-Jac Foods—are growing at a 10 percent CAGR, outpacing conventional foods, which have been growing at just 1 to 2 percent annually. The other half of pet spending is on a range of supplies and services, many of which sound remarkably human, including health care, grooming, spas, bakeries, insurance, day care, swimming lessons, psychotherapy, travel and hotels, and bedding.

The reason for this flood of pet-related spending is that Americans no longer think of their dogs and cats as pets, but as members of the family and as friends. A poll by the American Pet Association shows that humans welcome dogs and cats into their homes because they want “someone to play with” and “companionship.” Thirty percent of those polled said that they were as attached to their dog as they were to their best friend, 14 percent said they were as attached to their dog as to their children, and 10 percent felt as attached to their dog as to their spouse.

Although there was a rise in pet adoptions after the September 11 attacks, the fundamental drivers behind pet spending are the ones we have been discussing throughout this book—people are seeking ways to take care of themselves and make connections with others, whether human beings or animals. More and more Americans are living alone or as couples without children and feel the need for a live-in companion. Young childless couples, married or not, think of having pets as a way to “test the waters” of parenthood. Empty nesters see pets as a partial substitution for the children who now live away from home. Young single women and divorced women get a pet to provide protection, companionship, and solace. (Fortyfive percent of women aged thirty-five to fifty-four who have been divorced, separated, or widowed own a pet.) And, in addition to companionship, pets provide seniors with an activity that can fill their time and bring meaning to their lives.

Pets have been humanized in American society, and as a result become subject to the same benefits of trading up as human beings. Affluent and sophisticated consumers want the best for their dogs and cats, and they seek to make the most of the important emotional connection they have with them. This emotional need has led to the rise of New Luxury pet goods and the growth of the companies that create them.

The change began in the mid-1990s, when there was little differentiation among pet-food brands. Consumers bought these mediocre offerings out of necessity and resignation, but they were becoming ever more frustrated by their inability to provide for their pets as well as they wanted to. Increasingly, pet owners see themselves as nurturers and caretakers of their pets. According to a survey by the American Animal Hospital Association, some 83 percent of pet owners call themselves “Mommy” and “Daddy” when talking with their pets (up from 55 percent in 1995), and almost two-thirds celebrate the pet’s birthday. But the products available did not align with this emotional model.

Then a few small companies began to make technical changes in their products, making the recipes more healthful and improving the flavor and aroma; and they detailed each product to the pet owner’s most trusted advisers: veterinarians. The companies formulated foods to meet the specific dietary needs of different breeds of pets. They created “life stage” diets, designed for the requirements of animals of different ages. They offered a wider variety of food forms, including moist, dry, biscuits, cookies, pizzas, and more. They developed foods for animals with special needs and owners with particular requirements—foods that promoted shiny coats, did not upset sensitive stomachs, strengthened joints, or reduced the likelihood of hair-ball formation. The makers incorporated a variety of higher-quality ingredients—including real meat, organically grown vegetables, cheese, and garlic—as well as special supplements that improved product taste or promoted wellness, such as glucosamine for better joint health. And they marketed foods that aligned with religious, moral, and social values, including kosher pet food, “holistic” formulas, and “USDA inspected and approved” pet foods.

These technical benefits delivered performance benefits. Pet owners believed their dogs were healthier, looked better, were less picky in their eating habits, and were living longer or likely to do so. Most important, pet owners who treat their companions to premium foods and gourmet snacks feel they are developing a more loving relationship. They feel satisfied that they are taking good care of another being and at the same time taking care of themselves. Many owners also feel a sense of Questing in their pet ownership—they are learning the professional touch in pet management, providing their pet with all the benefits of foods developed, used, and endorsed by breeders, trainers, and other animal experts.

For these benefits, New Luxury pet-food brands can command a healthy premium. The Eukanuba Advanced Stage Veterinary Diet—Canine sells for $29 for a 16.5-pound bag, or about $1.75 per pound. Compare that to Iams Chunks at $17 for a 20-pound bag, or $0.85 per pound, or Purina Kibbles and Chunks at $11.49 for a 20-pound bag, or $0.57 per pound. Although New Luxury providers spend more to create their products, both in cost of goods and in marketing and distributing them, they are also able to achieve significantly higher margins. We estimate that a typical mass-market pet-food company achieves a 16-percent operating margin, while the smaller specialty brands can earn margins as high as 31 percent. The premium brands represent 20 percent of the sales volume in the pet-food category, but earn 55 percent of the profits. As a result, pet food has become an important New Luxury category, at about $12 billion in annual sales, growing—all segments combined—at about 4 percent per year.

The success of the small New Luxury pet-food companies has provoked changes in marketing and channel strategy for many players in the category. Mass merchandisers are carrying more high-end products and offering their own private-label products. This category is not immune from the trading-up and trading-down phenomena. Wal-Mart’s Ol’Roy is a product for frugal pet owners, and it has grown to nearly $1 billion at retail. Meanwhile, pet superstores are gaining ground as “category killers,” offering a broad range of food and nonfood products and services (including medical services and training). Ninety percent of food sales at Petco are premium products and brands. The losing channels are supermarkets that continue to carry primarily conventional products at middle-market prices.

We expect that the pet-care category will continue to grow in sales and profits faster than the pet population, with new players emerging and transforming additional segments of the category. As the number of nonfamily and singles households increases, it is likely that owners will devote even greater resources to their non-human companions, and the pets will gain even greater stature as family members.

As Mona told us, “Chloe’s great-grandpa sent her a birthday card this year. Her great-aunt sent her a new bowl. Her godmother brought her some organic catnip from Oregon. Chloe is not just part of my family—she is becoming the axis around which my family revolves.”