Eleven

A Cautionary Tale of an Old Luxury Brand: Cadillac

Well, there she sits, buddy, justa gleaming in the sun, right

There to greet a working man when his day is done

I’m gonna pack my pa, and I’m gonna pack my aunt

I’m gonna take them down to the Cadillac Ranch.

El Dorado fins, whitewalls, and skirts

Rides just like a little bit of heaven here on earth

Well, buddy, when I die throw my body in the back

And drive me to the junkyard in my Cadillac. . . .

Hey, little girlie in the blue jeans so tight

Drivin’ all alone through the Colorado night

You’re my last love, baby, you’re my last chance

Don’t let ’em take me to the Cadillac Ranch.

Cadillac, Cadillac

Long and dark, shiny and black,

Open up your engines, let ’em roar

Tearin’ up the highway like a big old dinosaur.

“Cadillac Ranch” by Bruce Springsteen

The Decline and Fall of an American Old Luxury Icon

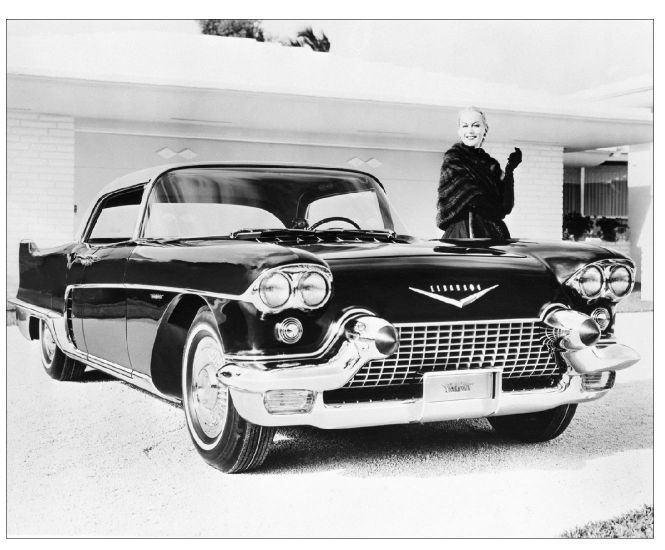

In the thirty years after World War II, Cadillac was the epitome of Old Luxury in the American car market—sleek, chromed, and elegant. Most of all, it was emotionally powerful, driven by the most glamorous celebrities—James Cagney, Gary Cooper, Joan Craw-ford, Bing Crosby, Cary Grant, Elvis Presley, and Jackie Kennedy. After World War II, the operations of German carmakers Mercedes-Benz and BMW lay in ruins, and, in Japan, Toyota struggled to build 27-horsepower vehicles, known in the industry as “Toyopets.” But General Motors, responding to the enormous postwar demand for consumer goods, had the resources and capabilities to create marvels of design—big cars, sporting more chrome than any competitive model. The name Cadillac became synonymous with status, achievement, and recognition, and the brand car became a cultural icon; it appeared in the most successful Hollywood movies, and singers crooned about it in more than a hundred ballads. “I love you for your pink Cadillac, crushed velvet seats, riding in the back, oozing down the street.”

Beginning in the mid-1970s, however, with the increase in imports from Japan and Europe, Americans’ definitions of quality and luxury began to change, as did our attitudes toward driving performance. General Motors found itself under siege from Toyota and Honda, whose cars offered higher quality at lower prices, and the company began to lose market share in its Chevrolet, Pontiac, Buick, and Oldsmobile divisions. Rather than increase investment in its crown jewel, Cadillac, General Motors starved it of capital and reduced its allocation of engineering resources. As a result, there were few technical improvements in the engine, suspension and handling, computer applications, and paint. General Motors relied instead on cosmetic “flash over function” design updates and superficial styling “improvements.”

The consumer was not impressed. With no meaningful technical or functional benefits to sell, the Cadillac dealer network was forced to offer heavy discounts just to move the metal. Although the premium-priced, luxury car market grew during the period of 1975 through 2000—from 5 percent of unit sales to 17 percent, and from 10 percent of profits to 25 percent—Cadillac units declined at a rate of 2 percent per year. The average age of the Cadillac owner climbed from forty-seven to sixty-two. This once-proud symbol of American triumph was nearly destroyed. What had been the ultimate statement of American class became a lament for a bygone era and the butt of jokes by stand-up comedians.

General Motors failed to understand that the American consumer was beginning to trade up to higher levels of quality, taste, and aspiration. The company was focused on other issues: competition from low-cost, high-quality Japanese cars, new fuel-economy regulations, the emergence of sport-utility vehicles (SUVs), increasingly complex and expensive safety and emissions regulations, and the resurgence of Chrysler and Ford as powerful domestic competitors. While General Motors was paddling hard to save its midmarket, midprice offerings, its competitors in Europe were building and selling a new kind of luxury vehicle that redrew the price-volume demand curve. BMW grew from $1 billion to $25 billion globally. Daimler-Benz grew to $40 billion. The Lexus division of Toyota, a latecomer to the market, grew from zero to more than $5 billion. And the premium car market is still on fire, the only segment that achieved growth and profitability in the down market of 2001 to 2002.

Cadillac is a cautionary tale. It shows that there is an important relationship between the high-end and midprice models in the automaker’s product range. When the superpremium model fails to offer technical and functional benefits, it can coast for a while on the emotional engagement—but not for very long. And no matter how successful—even iconic—a product is, it can swiftly be dethroned by competitors who understand the escalating tastes of consumers and invest in a benefit ladder that aligns with them. In categories of durable goods, the dethroning can take less than a decade. In consumable goods, it can happen in two years or less.

The Best Car in America

Henry Leland founded his company, the Leland Faulconer Manufacturing Company, in 1902, and he introduced his first product— the Cadillac Model A—in 1903. Leland was a machinist with long experience in the production of sewing machines (Toyota has a heritage in automatic looms), and by the age of fifty-nine, when he started his own company, he was an expert in precision engineering and quality manufacturing. Leland’s goal was to build the best car in America, and he decided to name his product after the French explorer Antoine de la Mothe, Sieur de Cadillac, who founded Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, later known as Detroit, in 1701. Monsieur Cadillac spent eight years at the thriving Great Lakes settlement until he was forced out of his post, was eventually recalled to France, and spent time as a prisoner in the Bastille. He never returned to North America. Perhaps the fall of explorer Cadillac foreshadowed the fall of the brand that bears his name.

The Model A was unveiled at the New York Auto Show with a price of $750 for the two-passenger model and $850 for a four-passenger version—as much as a 50-percent premium to competitive models. Even so, Leland’s sales manager took orders for 2,286 cars. It featured a single-cylinder copper-jacketed engine.

At the turn of the twentieth century, there were more than one hundred small automakers like Leland’s in the United States, all of them eager to take advantage of Americans’ thirst for mechanical transport. In 1903, entrepreneur William Durant began acquiring some of these producers and cobbling together a conglomeration that would become, in 1908, General Motors. In that year, Durant bought Cadillac from Henry Leland for $5.5 million.

As part of General Motors, Cadillac continued to make engineering advances. Leland had prided himself on advanced engineering and precision manufacture. In 1908, a British Cadillac distributor carried out a remarkable demonstration. He disassembled three Cadillacs, scrambled the parts, and then reassembled them. Everything fit together perfectly, and the three cars drove away—proof of Cadillac’s quality and ability to produce consistently interchange-able

Cadillac was the epitome of 1950s Old Luxury.

Copyright Bettman/Corbis.

parts. The company soon developed the world’s first production V8 engine, a massive power plant (for its time) that delivered seventy horsepower.

Cadillac also focused on the cosmetic and styling features of the luxury car. By 1924, the Cadillac came with chrome finishing and was available in a wide range of colors. In 1927, Cadillac launched the La Salle convertible coupe, with a side compartment for golf bag and clubs. In 1934, it introduced the first independent front suspension. A sunroof became available in 1938, and the 1941 Series 60 was one of the first models that offered air-conditioning as an option.

Before World War II, Cadillac was just one of several brands that competed at the high end of the US car market, but after the war, Americans were looking for a new way of life that celebrated the US’s triumph and put the deprivation and ugliness of war behind them—and that’s when Cadillac became the country’s leading luxury car. There were great opportunities available, and much new wealth, and Cadillac aligned its brand with the important emotional themes of the day: status and achievement. It was called the car “where a man is seen at his best.” It was designed “for the sheer joy of living.” With a Cadillac, “prestige is practical.” Cadillac was the car of “taste, quality, supremacy, an enriched life, a symbol of success.” By purchasing a Cadillac, you were demonstrating to your friends—and to the whole world—that you had made it.

From 1948 to 1977, Cadillac was the bestselling luxury car in the world and the car to own and be seen in. Dwight D. Eisenhower traveled to his 1953 presidential inauguration in an Eldorado convertible, complete with signal-seeking radio, automatic headlight dimmer, leather upholstery, and aluminum wire wheels. In 1955, Cadillac was so dominant it outsold its chief rival, Lincoln, three to one. During those years, Cadillac continued to innovate and offer technical and functional benefits that brought great pleasure to its owners. The 1958 Cadillac Fleetwood 60 Special was “loaded” with engineering advances—including a high-compression overhead valve engine, power windows, power steering, and power door locks—as well as chrome fins and fenders styled like fighter aircraft. The 1959 Brougham rested on a wheelbase of 149 inches, weighed 5,490 pounds, and delivered fuel “economy” of less than eight miles per gallon.

Then, as reliable, fuel-efficient imports from Japan, as well as safer and better-performing cars from Europe, entered the US market, Cadillac began its decline. The flamboyant fighter-jet styling suddenly looked outdated and superficial in comparison to competitors, including Mercedes-Benz and BMW, which offered better driving performance, greater reliability, and more total value. “I drove Cadillacs for twenty years,” says fifty-seven-year-old executive Gary. “In the early 1960s, we had a yellow Caddy with bright yellow interior. All the kids wanted a drive home from Little League in that car. But over time the quality declined. They priced up the cars but provided no innovations. They clung to their reputation, but it was an empty shell. Every three years I was buying the same car. New model year, but no changes. General Motors was milking the brand.”

By the late 1970s, Gary’s emotional engagement with the Cadillac brand was challenged. “My sons started to make fun of my Cadillacs,” he confesses. “They called them fat cars for old men. They joked about the steering and called them boats.” In 1982, Gary finally sold his Cadillac and bought the first of a succession of premium European cars. “Today I drive the supercharged V8 Jaguar,” he says. “I’ve gone from catcalls from my sons to admiration.”

In the early 1980s, when Mercedes-Benz and BMW were becoming serious players in the US premium-car market, Cadillac might have been able to respond to their challenge. But rather than try to understand the benefits these cars offered, Cadillac made half-hearted responses. To try to improve the fuel efficiency of its cars, it developed a diesel engine so poorly engineered that it became a further target for jokes, as well as the subject of consumer lawsuits. In response to Americans’ move to smaller cars, Cadillac developed the Cimarron, but it was built on a Chevrolet chassis and looked like a low-price Chevy Cavalier, gussied up with leather and chrome. Cadillac called it “a new kind of Cadillac for a new kind of Cadillac owner.” But it offered no technical or functional benefits and couldn’t even deliver on the one benefit the true Cadillac apostle still valued—the emotional engagement of a big, flamboyant car— at a relatively small 173 inches and 2,524 pounds. Cimarron sold 26,000 units in 1982 and went out of production in 1986, selling a paltry 6,454 units in that year.

Cadillac lost its leadership because it failed to understand the rules of New Luxury. First—partly as the result of labor strife and strikes at its manufacturing facilities—quality declined. Cadillacs were delivered with wide and uneven gaps between major body panels, ceiling insulation that peeled away, and interior panels with mismatched colors. New Luxury consumers have no tolerance for such defects and performance failures. Second, Cadillac failed to deliver new technical differences and benefits. Rather than invest in engine, suspension, and safety technologies, it relied on model refreshments that offered little more than changes to the shape of exterior body panels.

Most of all, Cadillac failed to understand the change in the emotional drivers of affluent consumers. They no longer wanted to buy Old Luxury cars that were designed mainly to convey status and that had become symbols of conspicuous consumption. They gladly paid a 25 to 50 percent premium for the European models that were better engineered, were more exciting to drive, and made them feel sophisticated and knowledgeable. What’s more, a Mercedes-Benz held its value better: After three years it could be sold for up to 70 percent of the original purchase price. A Cadillac lost 35 percent of its value as soon as it left the dealer’s lot; three years later, the seller was lucky to realize 40 percent of the original purchase price. Consumers’ sense of loyalty to the old image of Cadillac, as well as very generous financial incentives, were all that kept Cadillac’s share of the premium car market from declining faster than it did.

A New Definition of Premium: Performance

Mercedes-Benz challenged Cadillac as a different kind of Old Luxury car—safer, more conservatively styled, with higher build quality and engineering advances, but still designed to convey status and success. But it was BMW and Lexus that provided consumers with new ways to think about what a premium car should be.

Bayerische Motoren Werke, or BMW, was founded as an aviation engine company. Toward the end of World War I, its engines were installed in Fokker fighter aircraft, replacing engines made by Daimler (the producer of Mercedes cars). The BMW engines immediately proved to be more reliable, more powerful, and more responsive—pilots found they could fly higher and dive faster. BMW engines became known as the most dependable engines in aviation, and that heritage is still evident in the strategy and culture of BMW.

Between the wars, BMW produced both automobiles and motorcycles, but it returned to production of aircraft engines during World War II. One of its plants, in Munich, was destroyed, but other plants survived. BMW did not begin selling cars in the United States until 1954, and sales were small—under ten thousand units— throughout the 1960s. During its first two decades in the United States, BMW was a cult car, purchased by car aficionados and wealthy driving enthusiasts.

Today BMW, the producer of what the company calls the “ultimate driving machine,” has become the most profitable car company in the world. As a whole, BMW—with sales of 213,127 vehicles in the United States in 2001—achieved a greater profit, $1.87 billion, than any other major car maker. General Motors, with US sales of over four million vehicles, earned just $600 million; both Ford and DaimlerChrylser suffered losses. In the down economy of 2001, BMW’s US deliveries (cars and SUVs) grew 12.5 percent. In 2002, the company sold 256,622 vehicles (including MINI Cooper sales) in the United States, up 20 percent over 2001, and sold more than 1 million vehicles worldwide for the first time. By contrast, General Motors unit sales in 2002 were down 1 percent.

BMW has built its success not as an updated version of an Old Luxury car, but as a quintessential New Luxury brand. Dr. Michael Ganal, a member of the BMW board, told us: “BMW produces premium cars, not luxury cars. They are engineered by people who love cars. Other car companies concentrate on ‘visible’ features. We make the best vehicle. We are the advocates for drivers. We invented antilock brakes and traction control.”

BMW has extended its position in the premium segment through clever segmentation and maniacal adherence to its core identity as a producer of performance engines. It has made the brand both more accessible to middle-market buyers and more aspirational, with a top-price model (the Z8) at $131,500 and the lowest priced 3-Series at $27,800.

BMW introduces its new technical and functional innovations in the 7-Series, its superpremium sedan, starting at $68,500. The 2003 7-Series is loaded with technical features designed to increase handling, safety, performance, and driving comfort and that deliver functional differences competitive cars cannot match. In addition to a remarkably powerful and efficient 4.4-liter V8 engine that delivers 325 horsepower with 0-to-60-miles-per-hour acceleration in just 5.9 seconds, “enormous” ventilated disk brakes, and a drive-by-wire shifting system, the 7-Series also offers such advanced features as seats that adjust twenty different ways and a Park Distance Control device that signals as the driver approaches the curb. The car can monitor the pressure of its tires, and its headlights adjust their angle during hard braking to provide the driver with optimal visibility. The windshield wipers sense when it’s raining, and the washer fluid reservoir is heated so as to better prevent windshield icing. The driver can control the navigation system with voice commands. In case of an emergency, a Mayday system automatically opens a voice line to an assistance center, staffed by people who can help with any need. The Intelligent Safety and Information System monitors the car’s safety status with fourteen different sensors. And the iDrive system enables the driver to personalize the settings of many of the car’s interior controls.

The innovations introduced in the 7-Series soon cascade into the 5-Series, whose models start at $37,600, and the 3-Series, starting at $27,800. These models have enabled BMW to dramatically extend its reach into the middle market. In 2001, 67 percent of BMW sales came from those two models.

In 2001, BMW further extended its reach with the introduction of the MINI Cooper. The MINI is a small classic British car, revitalized with design updates and features that include (on the MINI Cooper S) a six-speed 163-horsepower engine, a six-speaker CD stereo, air-conditioning, and six airbags—offered at $19,425, about 29 percent less than the base 3-Series. It is managed by a separate division at BMW, with its own distribution system and marketing operation. MINI managers often say, “Please don’t call us BMW MINI. We’re just MINI.”

The MINI was launched with a New Luxury campaign designed to position it as an iconoclastic brand and to create apostles—its theme line: “Live me, dress me, protect me, drive me.” Consumers can customize their MINIs with colors such as chili red, velvet red, silk green, and pepper white. Options include some of the features pioneered in the 7-Series such as Park Distance Control and sensing wipers. An automotive expert says, “Pound for pound, inch for inch, there’s more fun and charm packed into the diminutive 2002 MINI than any car on the market.” Or as BMW claims in its new ad, “Small is the new black.” The car is a hit, acclaimed for its “fun and charm” and for being “frisky” and “nimble.”

Although BMW focuses primarily on the technical and functional benefits of its cars, company managers believe that emotional engagement is just as critical, and they have a thorough understanding of their core consumer. “Most car companies underestimate the psychographic,” says Dr. Ganal. “But we are a relatively small, independent company. We have less than two percent of US market share. We can’t play as big guys—we don’t have their large budgets.” BMW’s chief marketing officer in North America, Jim McDowell, describes the company’s target customers as people “who work hard and play hard. They treat fun seriously. They have high personal energy. Quality is very important, and they are prepared to pay more for it. They enjoy driving. Sometimes they don’t take the most direct route to work if there is a better road for driving. They feel completely at peace—protected and invigorated in their driving environment. They are far more likely to wash their cars than other people in the same income cohort. One of the company’s ‘management maxims’ is that it is the customer who decides on the quality of our work. The customer decides on BMW’s right to exist.”

Ted, a reconstructive surgeon who lives in Dallas, is a typical New Luxury consumer—although at the very high end of the income scale—and the kind of buyer BMW attracts. Ted’s wife is also a physician, and they have two children. In 1996, Ted bought his first BMW. “First we looked at a Lexus,” Ted explained. “But during the test drive, the salesperson drove it twenty miles an hour. Then we went to a BMW dealer and got a salesperson who used to sell cars for Lexus and Mercedes-Benz. She knew that she was selling a hot car with power. My wife went for a test ride, and she came back with her hair standing up. The car was a kick. It seemed as if it were airborne. She was on highway access roads doing eighty miles an hour and coming to a screeching stop. The brakes never failed. It was like being at Six Flags on a roller coaster, only better. I’ve now had four BMWs, and I’ll never ever drive anything else.”

BMW has steadily built its presence in the US market—even with substantial price increases over the years, BMW has grown 15 percent every year since 1995—by delivering cars that are thrilling to drive, that offer what owners call a “blend of sport and luxury,” and that stay true to the brand’s ethos. The company operates by strict design principles, which require the very best components, and it incorporates substantial innovations and improvements into every new model. The cars are among the most expensive in their product segments and therefore sell at premiums, but they are not about Old Luxury or status or conspicuous consumption. Even so, some consumers complain about the high sticker price, which is up substantially since the original launch in the United States, as a result of increased labor costs, intense application of technology, and fluctuations in currency. “We have design that lasts,” says Dr. Ganal. “We don’t change appearance for the sake of change. You can have a five-year-old BMW that doesn’t look old.”

Lexus: The Ultimate Reliability Machine

Lexus, the premium car brand of Toyota, presented a different kind of challenge to Cadillac and the other American luxury brands. Lexus patterned itself after Mercedes-Benz, knocking off the German carmaker’s flagship sedan, combining Japanese build quality and reliability with an interpretation of European styling.

Toyota began life as a manufacturer of weaving machinery. The Toyoda Automatic Loom Works Ltd. was founded in 1926 and began making automobiles in 1932. Its first model was a hybrid, built on a Chevrolet chassis, with a 65-horsepower engine and a Chrysler body. Toyota’s factories were converted to military production plants during World War II, but the company returned to car manufacturing in 1947. With Japan’s economy devastated, it took years for Toyota to gear up production. In 1955, Toyota was able to produce only seven hundred cars a month. But in the 1960s it dramatically increased production as well as exports to the United States. In 1960, Toyota shipped 6,500 units to the United States. In 1967, exports had grown to 150,000 units. And by 1969, Toyota had become the fifth-largest car producer in the world, after General Motors, Ford, Volkswagen, and Chrysler.

The ethos of the Toyota brand was, and is, quality. The company saw itself as a pioneer in the processes of manufacturing excellence, including just-in-time manufacturing; kanban, a component-tracking system to improve manufacturing work flow; poka-yoke, a system for “mistake-proofing”; total productive maintenance for perfect machinery availability; total system waste reduction; and jidoka, machines with “judgment.” The developers built feedback loops into the process, so they could learn from every error that was made on the assembly line. The Toyota Production System, also known as lean manufacturing, enabled Toyota to build cars quickly and cheaply, but with high levels of quality.

Throughout the 1970s, Toyota built its reputation in the United States on quality, fuel efficiency, and reliability—but the styling was bland and there was little driving excitement to be had in a Corolla. In 1978, Toyota launched its first premium model in the United States, the Cressida, with modest success. Then, in 1984, Toyota chairman Eiji Toyoda, cousin to the founder, challenged his engineering staff to create a luxury car to compete with the very best, which at the time was Mercedes-Benz. Toyoda assigned some four thousand engineers, technicians, and designers to the task of creating the new model, code-named F1. To better understand the potential consumer—the affluent, but value-conscious, American— the lead designers spent time in Laguna Beach, California, visiting and studying the American lifestyle. The team dined at fine restaurants, visited elegant homes, and purchased designer clothing. It was an early experiment in “patterning”—finding the key elements in a phenomenon, how they connect with each other, and how the pattern may be applicable to other phenomena.

The Lexus LS400 (Luxury Sedan) was launched in early 1989. It was priced at $35,000, a 40-percent discount to the competing models from BMW and Mercedes-Benz, but the same price as Cadillac. Each buyer received a book about the history of the Lexus and a letter from Toyota’s chairman saying, “In our language, we have a say-ing

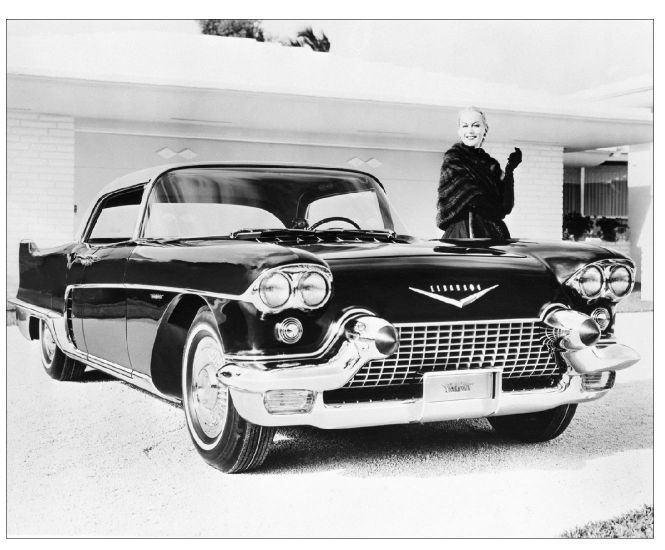

Today Mercedes-Benz makes and sells many more affordable masstige models than just a decade ago.

for the occasion when a daughter is given away in marriage. Here’s our cherished child—please take good care of her. This beautiful motor car is, indeed, our cherished child.”

The major publications covering automobiles seethed with enthusiasm: “The LS400 is a pioneering vehicle,” said Automobile Magazine. It was a “remarkable engineering achievement,” according to Road and Track. U.S. News & World Report said, “The LS400 is an exquisite automobile,” and J.D. Power and Associates crowned the Lexus “highest on customer satisfaction.” The car was applauded for superb ride quality, standard features, top interiors, and reliability higher than all other makes and models. Not everyone was impressed, however. It was dismissed by some German critics as being “less innovative” than their own cars and as being a knockoff that did not pursue “superiority and delight.”

Lexus was New Luxury in a different form than the performance-focused BMW and aimed at a different core consumer than BMW’s driving enthusiast—but it was a New Luxury product that delivered on all three rungs of the benefit ladder. Lexus offered technical improvements. The four-liter, four-cam, thirty-two-valve V8 engine used advanced electronics designed to reduce maintenance costs, cut down on vibration, and increase the stability of the car. Aluminum alloys were used to reduce weight. Toyota studied competitive vehicles and developed a list of ninety-six items that would increase the Lexus’s longevity, including a paint containing micaceous iron oxide, which resists corrosion. To the driver, these technical improvements translated into a car that was extremely quiet and comfortable, safe, reliable, and easy to maintain.

Lexus also delivered on the emotional level. The company built a dealer network separate from its established Toyota locations, with the showrooms built to a master design scheme, to create a sense of brand consistency and reliability. A dealer was required to display at least four vehicles in the showroom, with media support, and invest $5 million to $10 million in the display and service rooms. The sales staff were trained to promote the safety and service features, including roadside assistance, of the new brand.

Lexus was an immediate success, selling 63,534 units in its first year. By 1991, Lexus unit sales exceeded both Mercedes-Benz and BMW. Lexus expanded its range in 1993, introducing a performance sedan designed by the design studio of Giorgetto Giugiaro. In 1996, Lexus expanded the line with a four-wheel-drive SUV. In 1999, Lexus introduced its sport coupe with a “hard-top, one-button convertible.” Like the Mercedes-Benz SL500, the car featured a hard top that folded into the trunk in less than a minute—but the Lexus was priced 30 percent lower than the Mercedes-Benz.

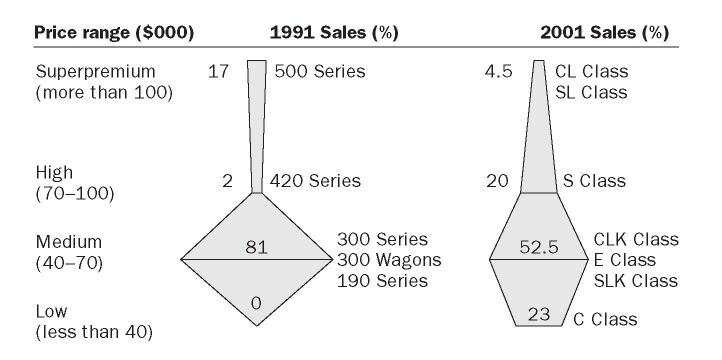

Lexus was an outsider to the American car industry and broke the rules. It delivered a near-death blow to Cadillac and provided tough competition for the German manufacturers as well. To combat Lexus, Mercedes-Benz and BMW not only revamped their product lines, they also reconfigured their pricing and subsegmentation strategies. In 1980, 70 percent of Mercedes-Benz sales came from its midprice product line, 21 percent from new entry-price points, and 9 percent from the high end. Today the midprice cars represent 45 percent of sales, with 28 percent at the low end, 21 percent at the high end, and 6 percent in a new superpremium segment. BMW followed a similar pattern. Both brands have become simultaneously more accessible and aspirational, with a top price that approaches ten times the lowest. In the down market of 2001, BMW’s unit sales grew 13 percent, and average unit price actually rose slightly. Mercedes-Benz, fighting both its integration with Chrysler and multiple product launches, saw both its unit volume and quality ratings decline.

A BMW in Every Driveway?

For the past decade, the premium car category has been the most consistent profit sanctuary for major manufacturers. BMW has become the most profitable major car company in the world. The Lexus division of Toyota delivers an estimated 35 percent of company profitability. Mercedes-Benz funded its purchase of Chrysler with profits from its high-end models.

Virtually every carmaker has tried to capitalize on the New Luxury phenomenon, offering line extensions of superpremium brands, or masstige models between mass and class. Porsche offers the Boxster at $44,000 in comparison to its 911 model, which starts at about $68,000. Mercedes-Benz has the CLK coupe at $42,000 and the SLK roadster starting at $40,000, half the price of the SL class, which starts at $84,000 and sells for as much as $133,000. And BMW sells its Z4 for about $33,000. The cars come equipped with leather seats, cruise control, high-quality sound systems, traction control, emergency communication systems, and more. And each one meets a specific emotional need for the New Luxury buyer.

In the next few years, New Luxury auto manufacturers will extend their brands in new directions and test their ability to maintain the brand ethos while extending its scope and embracing a larger number of consumers. Mercedes-Benz is seeking to push the aspirational limit much higher with its superpremium Maybach models, at prices over $300,000, but it may find that the new model is so far out of reach for middle-market consumers that it is emotionally meaningless to them—just as its 600 model was and as Rolls-Royce and Bentley now are. Porsche has entered the SUV market with its turbo-charged Cayenne model, selling at up to $100,000. It is a very different kind of SUV than the Ford Explorer, capable of delivering 450 horsepower and has a top speed of 165 miles per hour. Concerned that the Cayenne might alter the emotional engagement of the brand and disaffect the Porsche 911 driver, the company claims that Cayenne will “be a one-of-a-kind with the made-in-Germany quality seal. The heart of the matter, as you’ll guess, is the genetic code. The Cayenne won’t be hip. The Cayenne will be engineered.”

As new makers continue to enter the premium market with New Luxury models, there doubtless will be overcapacity. The winners will be the companies that offer genuine technical and functional differences and that continue to enhance them with each model year. Most important, they will deliver the emotional engagement their consumers expect. As soon as the BMW driver detects a bit of mushy handling, or the Lexus driver is treated poorly by a service technician, or the Mercedes-Benz driver notices a sloppy bit of finish work, he becomes a candidate for switching to a different brand. He will not maintain his loyalty for decades as the Cadillac consumer did.

Starting in the late 1990s, Cadillac began taking steps to reverse the decline of its iconic model. General Motors recruited Robert Lutz, former head of Chrysler, to help return Cadillac to its glory days. “GM had to finally come to terms with the fact that it had allowed the Cadillac to deteriorate,” Lutz told the Economist. “It had not received the amount of investment and engineering attention that a premium brand would have had if it was stand-alone. Now the company is allocating the money Cadillac needs.”

The company has developed a new body style that is still reminiscent of a fighter aircraft, but a technologically sophisticated stealth fighter. The engine is a sturdy 4.6-liter V8 branded Northstar, tested on the same German road tracks as BMW and Mercedes-Benz. Cadillac is forming new alliances to improve the perception of its cars as performance vehicles—it has become the official supplier of cars to the Bob Bondurant School of High Performance Driving, and the Cadillac CTS models will be customized with racing wheels, rollbars, and dual exhaust.

Although the Cadillac CTS model achieved 16 percent growth in sales in 2002, it may be that Cadillac’s enhancements will be seen as simply more of the same old story—changes that do not bring meaningful difference or a new kind of emotional engagement. Cars can be important in all four emotional spaces, but Cadillac will have a difficult time making the case that it is the best car in any one of them. For those who are looking for a Taking Care of Me car, Cadillac won’t measure up in terms of safety and comfort in comparison to Lexus. For those who think of a car as a facilitator of Connecting, Cadillac may work for the over-sixty audience, but it is doing much less hooking up than are younger buyers. Cadillac, with its big frame, soft ride, and mushy handling cannot compete with BMW, Porsche, or Mercedes-Benz as a Questing car. And, finally, as an indicator of Individual Style, Cadillac still says, “Out of it.”

A return from the dead is unlikely in New Luxury. BMW, Mercedes-Benz, and Lexus have already so transformed the market— making their cars more affordable at the low end and more aspirational at the high end—that Cadillac may not be able to escape death in the middle.