Twelve

The Opportunity: Growth Areas, a Work Plan

America has not finished trading up.

The phenomenon is almost infinitely extendable because the capacity of businesses to innovate is unlimited and the emotional needs of consumers are never entirely filled. So for entrepreneurs and business leaders, the trading-up phenomenon represents a tremendous opportunity—for business growth, increased brand and company vitality, category leadership, and disproportionate share of profits. The list of categories waiting to be transformed—or transformed once again—is long indeed.

But trading up also poses a threat to many businesses. The entry of New Luxury goods generally leads to polarization in its category. Consumers gravitate toward the premium New Luxury goods if that category is important to them. If it isn’t, they trade down to low-cost goods. That can often lead to death in the middle for those brands and products that offer no specific reason to buy: a significant price and cost advantage, a genuine technical or functional difference, or an emotional benefit.

Managers of conventional businesses that are threatened with death in the middle often protest, “We can’t create a premium product in our category. There’s no volume at the high end!” Or, “Our product is a commodity—there are no real differences. We can’t create emotionally satisfying goods.” But there are emotional issues lurking in every product category, and where there is emotion and a product difference, there can be volume and profits.

As we’ve explored in this book, New Luxury goods have transformed many categories—including laundry and kitchen appliances, luncheon restaurants, beer, vodka, lingerie, coffee, pet food, toys, and golf equipment—and they will likely do the same in dozens of others that currently lack a brand that offers quality, technical difference, functional superiority, and genuine emotional satisfaction.

The results of our survey show, in fact, that there are many categories that consumers say are emotionally important to them, but in which they currently have few options for trading up.

Categories to Watch: Coffee Replacement and High-Performance Athletic Wear

New Luxury goods, as we have seen, can emerge in any category, and consumers can find themselves eager to trade up to these premium brands even when they had no strong previous interest in the category. Two examples of New Luxury goods that have the potential to transform their categories are premium tea and high-performance athletic clothing.

Since the ascendance of Starbucks as the quintessential New Luxury purveyor of coffee drinks (and the emotional engagement attendant to their consumption), business observers have been looking for the challenger that could again transform the world of hot beverages and that challenger might well be coffee’s ancient rival: tea. Although the number of cups of tea consumed per capita in the United States has been decreasing for the past decade, dollar sales of tea are on the rise—up from less than $2 billion in 1990 to more than $5 billion in 2002. And consumers with household incomes of $75,000 or more are the major tea purchasers.

The tea category is beginning to polarize. Sales through mass-market distribution channels of conventional teas—such as Lipton, Twinings, and Bigelow, as well as the main player in herbal tea, Celestial Seasonings—are growing slowly, if at all. Although these brands have long offered a variety of teas (from different countries and with different blends and added ingredients), the category has been relatively static, with little brand differentiation, technical innovation, performance improvement, or new understanding of the emotional engagement to be had with tea. Premium teas sold through specialty outlets, by contrast, are achieving record sales and growth and creating a base of enthusiastic consumers. The New Luxury tea brands offer new ways for consumers to engage with tea that go well beyond the drink as irrigation and refreshment.

Take Tazo, for example, with its “The Reincarnation of Tea” tagline. Founded in the early 1990s by Steve Smith, Tazo supplies high-quality specialty teas that appeal to the tea connoisseur. Tazo advocates say they can easily distinguish the difference between the taste of Tazo Zen Green Tea & Herbal Infusion and plain old Lipton green tea. Tazo has other technical differences, as well, including attractive, easy-opening packaging that contains with a printed plea for recycling. (“Please recycle,” reads the label. “This box deserves to be reincarnated too.”)

Other New Luxury tea providers offer their own technical innovations. Teas from The Republic of Tea come in round sachets, which they claim are “environmentally friendly” with no “wasteful strings, staples, and tags.” Their products can also be purchased as loose tea, for brewing in the pot or in tea strainers for a single cup. Kusmi-Tea comes packaged in muslin bags, for quicker infusion.

The New Luxury tea brands, as with most successful New Luxury products, are marketed with compelling stories that focus on the historical and natural origins of tea. These stories add to the vitality of the brand and make an emotional connection with the consumer. Tazo, for example, takes its name from the tazo stone, which the company purports to be an ancient stone that was discovered by a team of archaeologists and “tea scholars” in the late 1980s, and contains arcane language describing formulas for tea. Although the tazo stone appears to be a marketing invention, it works as an insider’s slightly tongue-in-cheek story that builds attraction to the brand. The Republic of Tea similarly seeks to create a whole world centered around its philosophy of tea. “When we set out to form our small Republic,” reads their Web site, “we had a mission to create a Tea Revolution. Our not-so-covert agenda was to transport all among the leaves, where tea awakens us to the truth of our own existence. Through a simple cup of tea, one can realize the supreme true reality of TeaMind.” Kusmi-Tea links itself to a true story, based on its Russian heritage as purveyor of teas to the tsars until the Revolution of 1917, at which time Kusmi-Tea relocated to Paris.

Most important, New Luxury teas have a strong emotional component, appealing to three of the four emotional spaces that are associated with trading up. Many tea lovers think of the drink as essential to Taking Care of Me. In cultures around the world, enjoying a cup of tea has traditionally been considered a reliable way to achieve a soothing moment of relaxation, personal reward, and revitalization. But now many consumers think that drinking tea provides personal health benefits that extend well beyond the moment of enjoyment. This may be the result of medical and scientific studies whose findings show that tea can help lower the level of cholesterol in the blood, reduce the risk of certain cancers, sweeten the breath, and reduce the effects of aging. New Luxury teas are also about Connecting; their consumers align themselves with the brand values, which are mostly related to respect for the Earth, organic production methods, and resource conservation. And, as with wine, New Luxury tea drinkers can do some armchair Questing, vicariously visiting such exotic tea destinations as Malaysia, Kenya, Russia, Sri Lanka, and Tibet.

Starbucks appears to agree that New Luxury tea could be a coffee replacement. Starbucks has been so successful serving Tazo teas in its stores that it bought the company in January 1999. Starbucks sells a tall Tazo hot tea for about $1.20 and has more than tripled its retail tea business since 1999. Tea beverages, including chai tea, which is mixed with milk and spices, account for about 7 percent of Starbucks’ revenue, up from 1 percent before the Tazo acquisition.

“We have seen significant growth,” said Steve Smith, Tazo’s founder, who now runs the company as a Starbucks unit. The collapse of the innovation cascade, which has characterized the coffee business in recent years, has come to tea. “Shaken iced tea with fruit juice was a phenomenal tea last summer,” said Smith. “It adds a sense of theater, but it does more than that. It incorporates oxygen into the beverage and makes it taste better.”

Tazo’s quality and branding enable it to command a premium over traditional brands in the supermarket, as well as in the shop. A twenty-count package of Bigelow tea sells for $2.00, or $0.15 per bag. Tazo sells at a premium in excess of 50 percent: $4.59 for a twenty-count pack, or $0.23 per bag. A fifty-bag container of Emperor’s White Tea from The Republic of Tea sells for $13.49, or $0.26 a bag.

Although much of the growth in premium teas has been in supermarkets and specialty stores, the greatest future growth may come from specialty tea shops. Lipton Foodservice, a unit of Unilever, was an early mover in this segment, establishing The Lipton Teahouse in Pasadena, California, in late 1996. The shop was promoted as a high-end teahouse experience and Lipton announced plans for creating a chain of two hundred or more teahouses nationwide by 2000. This has not come to pass, most likely because Lipton failed to convince consumers that it could deliver on the New Luxury ladder of benefits. Lipton is a conventional brand that shows every sign of being stuck in the middle. It is not the cheapest tea, but it offers no technical and functional differences that might justify its price. Nor does it have a brand story to tell beyond the image of the mustachioed fellow on the familiar red and yellow box, and the rather cryptic claim that the tea is “brisk.” Lipton is now attempting to attract the trading-up consumer with its premium Sir Thomas Lipton line.

Argo Tea, with tea shops in Chicago, is more likely to succeed in capturing the Trading Up consumer. The shop sells signature tea drinks such as “Carolina Honey Breeze,” a blend of honey, tea and lemon, “Tea Squeeze,” a mix of hibiscus iced tea and lemonade, and “Tea Sparkle,” tea with soda water and flavored syrup. These specialty tea drinks, which sell for $3.95 for a large size, offer distinct technical benefits over other teas in the teahouse market. For example, Argo blends its own chai, using natural ingredients from India and China. Starbucks chai, by contrast, is an artificial flavoring.

Although Starbucks and Dunkin’ Donuts are not yet in serious danger from the tea upstarts, the teahouse movement is growing. A company called Tealuxe operates tea rooms on the East Coast and hopes to grow by franchising their concept. Teaism has shops in Washington, D.C., and claims that they offer “an alternative to the obfuscation, over-formalization and xenophobia of traditional Asian and English teahouses.” On the West Coast, tea shops dot the landscape in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Portland.

“The race is on to see who can get a successful tea chain in gear,” says Brian Keating, a tea expert and marketing analyst with the Sage Group in Seattle. “The question is who and when, not if.”

Another category where established brands may be challenged by a New Luxury entrant is athletic clothing.

Under Armour, based in Baltimore, was founded in 1996 by former University of Maryland football player Kevin Plank. After seeing football players having to change their moisture-retaining cotton shirts three times during the course of a single practice, he began to research and design an athletic T-shirt that would deliver technical innovations, performance improvements, and hip fashion styling. The first year, he sold his line of moisture-wicking T-shirts out of his car, and had sales of $17,000. Since then, Under Armour has taken off, with its line of gear expected to reach $200 million in sales in 2004.

The distinctive element of the Under Armour product is “compression.” The garments are constructed of a moisture-wicking fabric that is not unusual in premium sports clothing, but they are designed to fit far more snugly than competitive garments. So snugly, in fact, that the underwear seems to compress and harden the muscles and form a kind of high-tech, lightweight armor that protects and supports the athlete in training or on the field of play. Under Armour claims that its compression garments are not only more comfortable than other sports clothing, they also provide better muscle support and decrease the wearer’s fatigue. In addition, because the fabric disperses heat, the garments are said to help athletes sweat less and therefore stay hydrated longer.

Under Armour positions itself as a serious brand for serious athletes. It has caught on particularly with young sports enthusiasts, ages twelve to sixteen, who are beginning to test their mettle in team sports and individual competitions and want to gain all the technical advantages they can and also be cool (as in “stylish and popular,” as well as not physically overheated). Under Armour products have also proved to appeal to the aspirational athlete, who can rest assured that should he actually work up a sweat, the moisture would immediately be wicked away.

For both the real and would-be athlete, Under Armour products command a premium: The standard long-sleeve compression shirt sells for about $50. Yet, as with other successful New Luxury brands, its premium price point has not relegated it to a niche role. In its core “compression” market, Under Armour commands an estimated 80 percent share, with Nike a distant number two with a mid-single digit market share.

By combining a commitment to performance with a sense of fashion, Under Armour has appealed to consumers in two important emotional spaces: Questing and Individual Style. Under Armour presents itself as a brand about authenticity, rather than of pop culture; a brand that offers real benefits, not just a marketing story. As evidence of this claim, the company says it produces its core products in basic colors only, unlike other sports clothing manufacturers who follow the practices of the fashion world by offering fresh colors each season. Under Armour also claims to have never paid a product placement fee. Rather, it has built its brand awareness through influence marketing. Roger Clemens was apparently so enamored of Under Armour that he appeared for free in early ads. Under Armour has also gained exposure through placement in movies, and is often seen being worn by professional athletes in their post-game locker room interviews. Under Armour supplies its gear to many major professional sports teams in baseball, soccer, football, and hockey.

Like other New Luxury companies, Under Armour has continued to innovate. It has expanded its line beyond underwear, to outerwear and other loose-fitting garments. So far, it has performed well in this segment, gaining an estimated share of the loose-fitting market of around 15 percent. Under Armour also has worked to diversify its customer base, partially by venturing into women’s clothing. While the majority of sales are still to males ages twelve to twenty-four, the consumer profile is changing quickly.

Under Armour exceeded $50 million in sales in 2002, and analysts have estimated 2003 sales at $110 million. In 2003, Under Armour ranked second on the 2003 Inc. 500, a ranking by sales growth of privately held US-based companies in all industry segments. The magazine reported that Under Armour achieved 12,753 percent growth over the previous five-year period. Under Armour was also named one of Fast Company’s “Fast 50” in the March 2003 issue.

While Under Armour is still tiny in comparison to giants such as Nike (at almost $11 billion in 2003 sales), it has the potential to polarize and transform the category.

The Opportunity in Services

There are many opportunities for growth in consumables, such as tea, and durable goods, such as clothing, but the greatest potential for New Luxury growth may lie in services, including financial and legal services, educational and health-care services, elder care and child care, pet care, travel and real estate, car care, and home maintenance services.

We are already seeing the emergence of New Luxury in some professional service categories, such as health care. Personal Physicians HealthCare, for example, cofounded by Dr. Jordan Busch and Dr. Steven R. Flier, charges a $4,000 annual premium to become a patient in the practice and delivers on all three benefit levels. The most important technical difference is that each doctor limits his practice to three hundred patients, rather than the average three thousand of a conventional managed-care general practice. There are further technical differences, including the design of the facility— which looks and feels more like a luxury spa than a doctor’s office— and a custom-designed software program that enables doctors to access patient files from a computer anywhere in the world. The differences in performance are striking: Patients can get same-day appointments; annual physicals last ninety minutes or longer and include conversation, advice, and detailed recommendations; doctors make house calls and sometimes accompany their patients to see specialists; and doctors and staff are always available by telephone or e-mail.

Consumers who choose Personal Physicians HealthCare told us they do so because the practice fulfills important emotional needs. Health care is primarily, of course, about Taking Care of Me, and most of the patients who choose the practice have health concerns— they are looking for more than an annual checkup and an occasional prescription for antibiotics. Although Busch and Flier are careful to say that they do not consider themselves more expert than their colleagues at conventional managed-care practices, they do believe they can give their patients more time and more focused attention.

New Luxury health-care patients are Connecting—they want to build a relationship with their doctor. They get to know him personally, and he knows not only their health history but their life story as well. They are also Questing. There are many patients who prefer the authoritarian doctor who “knows best,” but the patients at Personal Physicians do not fit that description. They tend to be people who are generally interested in health and wellness issues, whether or not they are immediately relevant to their own health. They like to learn about health, seek new ways to advance their own well-being, and take actions that will avoid illness. At Personal Physicians, they have more time to discuss issues of interest with their doctors—discussions that physicians in a conventional practice would have to limit due to their heavy patient load and tight appointment schedules.

Although premium health-care services, also called “concierge” health-care services, have been criticized as elitist, the doctors at Personal Physicians say their goal is to deliver the kind of health care that all physicians would like to provide but are unable to because they are so hampered by the complexities of managed care. In addition, they say they are now able to provide more pro bono care to disadvantaged patients and communities than when they practiced in conventional health-care groups. Because Personal Physicians HealthCare has been operating for only a year, it is too early to tell whether it will enjoy the kind of financial results that creators of New Luxury goods typically have. But it has had little trouble attracting patients and, to date, the company is exceeding the financial targets of its business plan. In 2003, Busch and Flier took on a third partner. In 2004, their practice was full.

New Luxury could extend even deeper into the services realm by transforming public and quasi-public services such as transportation and education. Limoliner, for example, is a premium bus service that travels the Boston-New York route. The vehicle is a luxury coach, said to cost about $500,000, that seats twenty-eight passengers, in comparison to the fifty-five-seat capacity of the standard bus. The fare is $138 round trip, cheaper than a limo and less than half the cost of the airline shuttle, at $411 round trip, but more expensive than the $55 ticket on the standard Greyhound bus. Eightyfive percent of Limoliner’s passengers are business travelers who seek a better class of service at a reasonable fare. “We are not trying to take everyone,” says Joe Cavallaro, general manager of Limoliner. “We are only trying to take a certain segment of the market by providing a higher level of touch and experience.”

The Limoliner, although a coach, has the kind of New Luxury technical differences you might expect in a limo, including roomy leather seats, power outlets, television, Internet access, food and beverage service, a ten-seat conference center, and a personal travel attendant who provides onboard concierge service. The technical and functional differences bring emotional benefits; passengers feel they are paying a premium to reduce the stress of dealing with airports and security woes. Dr. Rosanna DeMarco, a passenger, said about the Limoliner, “What’s not to love?” Launched in October 2003, Limoliner is off to a strong start. Friday afternoon and Sunday night trips are often sold out. Ridership has grown at 15 to 20 percent per month since launch.

In education, given the American interest in learning and the current difficulties of public schools, there may be a market for tools and methods of instruction and knowledge attainment that are more effective and more satisfying than current methods of teaching.

The Opportunity Worldwide

There are many opportunities for growth in both products and services in markets around the world, because the sociodemographic factors that have driven the trading-up phenomenon in the United States are also at play worldwide. As they have in the United States, these factors have provoked a shift toward a consumer-driven economy in other nations, and have stimulated growth in the premium, New Luxury, segment of goods and services, and will continue to do so.

The most important factor is the increase in consumers’ income and discretionary wealth. In Europe, household incomes have increased steadily over the past thirty years, even more than they have in the United States. Household wealth has also increased, driven in large part by a rise in home ownership and a steady growth in property values. Consumers in Europe have also benefited from the proliferation of mass retailers and large discounters, which, by offering low-cost goods in many categories, have freed up significant flows of money for consumers to spend on discretionary items. In addition, there is far more credit available to consumers. In the United Kingdom, for example, consumer credit outstanding per capita has risen almost 13 percent from 1993 to 2002. France, Italy, and Spain have also seen large increases in outstanding consumer credit. Germany, however, has experienced only modest growth in outstanding consumer credit, rising 2.5 percent over the ten-year period.

The social structure is also changing in Europe, and in ways similar to the changes in the United States. Women have increased their influence and roles in the economy and workplace. In all European countries, women work more, earn more, and have greater influence on purchase decisions than they used to. There are many more unmarried people. The rise of single women has increased dramatically, although less so in Europe than in the United States. When people do marry, they tend to marry later in their lives, delay having children, and have fewer children when they finally do have them. The average household size is decreasing. Many women continue to work after marriage and after childbirth, causing a rise in dual-income households. There has also been a strong and consistent increase in the number of divorces.

The nature of the European consumer has also changed. More European consumers have a greater amount of education than before, and the level of education is continuing to increase. More Europeans are traveling to international destinations. They also have been exposed to a steady increase in advertising and product promotions. In France, for example, consumers’ exposure to advertising has increased by 60 percent over the last fifteen years. In Germany, exposure to TV advertising has increased by 85 percent over the last six years. And, just like Americans, Europeans feel the stresses and pressures of complex, fast-paced lives. They feel anxious and pressed for time.

There are also differences between the sociodemographics of Europe and those of the United States that result in differences in trading-up behavior and the look of New Luxury in Europe. Although there has been a steady rise in household income in Europe, there are still many fewer European households with incomes of $50,000 and up than in the United States. As a result, there currently are fewer households that regularly trade up in several categories, which means there is plenty of room for growth.

The growth in income in Europe has been more evenly distributed across brackets, so the percentage of very high-income households is smaller than in the United States. Throughout Europe, especially in France, but also in Germany and Italy, there has been a stronger increase in income for the middle- and lower-income quintiles. This increase, combined with greater access to credit, has enabled many more households to trade up in a limited number of categories, while trading down simultaneously in others—the behavior known as “rocketing.”

Another difference between Europe and the United States is the high percentage of seniors in the population. People sixty years and older account for 21 to 23 percent of the European population versus 16 percent in the United States. These seniors have significant purchasing power and have demonstrated a propensity to spend on New Luxury goods that offer emotional engagement. As in the United States, European seniors constitute a market that is currently underserved with New Luxury goods.

The four emotional spaces we identified in the United States— Taking Care of Me, Connecting, Questing, and Individual Style— also drive European consumers, but with some nuances. For example, European consumers tend to be even more focused on authenticity than US consumers and care a great deal about the provenance of their goods. They are also more focused on Individual Style, especially as expressed in clothing and personal accessories, than US consumers.

In the United Kingdom, there has been an increase in the percentage of the ethnic population, including people from Africa, India, Pakistan, Asia, and the Caribbean, which has brought an influx of new influences, styles, tastes, and product preferences into the country. It is this kind of exposure to unfamiliar and exotic goods that often fuels the development of New Luxury goods and influences the wider population, and it is likely to cause a proliferation of such goods throughout the United Kingdom.

In France, sophisticated consumers are similarly keen on the genuineness and authenticity of their premium goods, including where and how they are made and what goes into them. According to Babette Leforestier, of the French research firm TNS Secodip, “The claim of authenticity is one of the major trends in consumption and the ingredients strengthen the image of these products as genuine.”

French seniors are already noted traders up. People fifty years of age and older account for 33 percent of the population in France. They earn 45 percent of net domestic income and hold 50 percent of the net financial assets. They represent a market for goods and services estimated to be about €150 billion in size. Their favored categories include premium hotels, custom kitchens, mineral water, and high-end automobiles.

In France, in addition to the well-known premium global brands, several New Luxury brands have emerged that are known primarily in the European market, demonstrating that the practices of New Luxury leaders in the United States work just as well in other places. Actimel yogurt, for example, is a highly successful New Luxury food product created by The Danone Group, based in France. Danone is a global company offering a variety of food products, in three main groups: fresh dairy products, beverages, and cereal biscuits and snacks. They have a portfolio of well-known brands, including Danone, the leading dairy products brand worldwide; Lu, the world’s second largest cereal biscuit and snack cracker brand; Evian water; and Dannon in the United States.

In 1997, Danone introduced Actimel, a single-serve drinkable yogurt that sells at a substantial premium to conventional yogurts and has achieved remarkable growth since its introduction and, in fact, has helped to build the entire market for yogurt-related products. Actimel is a New Luxury product that offers a genuine technical difference that translates into functional benefits for consumer and that strongly appeals to the Taking Care of Me emotional driver.

Danone developed Actimel in response to consumer research that the company conducted in the mid-1990s. The findings showed that consumers believed that yogurt could be healthy or it could taste good, but not both. The healthy yogurts were seen as functional food, even medicinal. The good-tasting yogurts were seen as convenient snacks, but less healthy than other brands. Actimel was conceived as a premium product that would break the yogurt compromise. It would deliver all the health benefits of genuine yogurt, with all the good taste and convenience of the more popular consumer brands.

The key technical difference of Actimel is an exclusive ingredient, a bacterium called Lactobacillus Casei Imunitass—L Casei, for short—that has specific impact on the intestinal flora. L Casei resists the digestive action in the stomach so that it arrives at the lower intestinal tract intact. It is then assimilated by the intestinal flora and reinforces them for better natural defenses. The ingredient, known as a probiotic, is patented by Danone.

The dual benefits of Actimel, as both a healthy and an enjoyable food, are reinforced in its packaging, presentation, and marketing. Actimel is packaged in small individual “doses,” a 62.5 ml bottle that is easy to drink from and convenient to carry. It comes in a large variety of flavors, all of which have a fresh, slightly acidic taste that is refreshing without the overly sweet taste of conventional flavored yogurts. Many consumers drink Actimel as part of (or all of) their morning routine, which makes them feel satisfied, well nourished, and healthy. Actimel claims that its yogurt helps the body resist fatigue, reduce stress, and avoid the intestinal imbalances that can result from eating other types of foods. Danone’s communications with consumers stress the distinct and unique properties of the L Casei probiotic, and describe the research conducted by the six hundred scientists and engineers at its central research facility. Danone asks consumers to take the “Actimel Challenge.” If they do not feel the health benefits of regular consumption of Actimel within two weeks, they can get their money back.

Actimel sells at a 100 to 500 percent premium over conventional yogurts. It is a highly profitable product for Danone, earning gross margins estimated at 30 to 50 percent. Actimel currently holds a 4 percent value market share of the European yogurt market, and it is expected that market share will reach 8 to 10 percent by the end of the decade. Actimel is the solid leader in the probiotic segment it created. In the United Kingdom, Actimel enjoys a 57 percent share in the UK probiotic segment, which grew from £3M in 1998 to £75M in 2002. By 2000, Actimel was available in fifteen countries, and sales were growing at 40 percent annually. Actimel has achieved a 59 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from its introduction in 1998 through 2002, and is expected to achieve a 27 percent CAGR in the next three years. According to Frank Roboud, CEO of Danone, Actimel alone drove 0.5 percent incremental growth for the entire group in 1999, a company that had sales of €13.5 billion in 2002.

Japan is also an important market for trading-up activity, with many similarities to the United States and Europe, but significant differences as well. The most noteworthy difference is the influence of two important consumer segments. One is the group of about 5 million young working women who live at home with their parents and have very low living expenses and thus have most of their income available for discretionary purchases. Known as “parasite singles,” these young women spend up to 10 percent of their annual salary on fashion items, and are the largest-spending segment of Japanese society.

The other segment is Japanese seniors. There are some 10 million baby boomers, people born between 1946 and 1951, and they compose the largest single group of the population of about 127 million people. There are some 50 million Japanese over the age of fifty, almost 40 percent of the total population. As these consumers approach and enter retirement, a number of forces cause them to spend more freely on quality goods that provide emotional engagement. In a typical household, the housing loan has been paid off. The married couple may be living on the husband’s pension and savings, but the wife may be working part time, as well. The couple may have one or two parasite single daughters living at home. Although these young women generally pay no rent, they may contribute to household expenses. The daughters play a very influential role in the purchase of goods, however. They bring home personal-care products, clothing and fashion accessories, and they make strong recommendations to their parents about the purchase of household appliances, travel, cars, and other goods. Sometimes mother and daughters will go to the spa together, and mother will be enticed to join after a visit or two. The result has been a remarkable rise in spa membership among people age fifty and older, increasing from 15 percent of all spa memberships in 2002 to 26 percent in 2003.

Although these two groups enjoy substantial discretionary wealth, average household income has been on the decline in Japan, as has consumer spending in general. The result is that consumers purchase goods very selectively, trading down in many categories. This behavior has been facilitated by the rise in mass retailing and discounters such as Tsurukame, a supermarket whose goods sell at about 20 percent less than similar products at Daiei.

New Luxury goods, including both global brands and national brands, have had success in Japan in many categories, including food, personal care (particularly skin-whitening cream), cars, and home appliances, especially tankless, automatic-open toilets. New Luxury has been particularly strong in such low-ticket categories as soy sauce, cooking oil, and ice cream, which can sell at premiums as high as 200 percent over conventional brands. These brands move off the traditional demand curve, selling with higher margins than conventional goods and in higher quantities than superpremium competitors. Soy sauce, like olive oil in the United States, has become an iconic New Luxury product. Premium soy-sauce brands boast such technical differences as organic ingredients and traditional distillation processes. They also promote the provenance and brand story, including the family history of the owners, and the special qualities of the region where the product is produced.

In automobiles, Nissan has found a particularly sweet spot in the market for its premium sports coupe, the Fairlady Z. It competes with the global New Luxury sports coupes, including the Audi TT, Porsche Boxster, Honda S2000, and BMW Z3. It matches or exceeds their technical specs in many aspects, including engine power and torque, but sells for less than half the price of the Boxster and about 13 percent less than its Japanese rival, the Honda S2000, in the Tokyo area. As a result, average monthly sales of the Fairlady Z dramatically outstrip its rivals; from August 2002 to June 2003, average monthly sales were 1,457 units, in comparison to 186 units for the Audi TT and 47 for the Boxster.

Factors That Will Contribute to the Spread of New Luxury

Just as New Luxury has arisen as the result of the confluence of social changes and business capabilities, both in the United States and in other markets, its spread will be further enabled by a number of factors:

Greater globalization and influence of overseas markets. As the European Union continues to expand and accept new member nations, and as China and other Asian countries become increasingly welcoming to both businesses and travelers, the trading-up phenomenon will become more globally influenced. Consumers will discover new tastes and styles, ideas and interests, and look for their Americanized versions back home. Businesses will have greater access, at lower cost, to ideas and supply chain services in countries throughout the world.

Heightened role of the Web and e-commerce. E-commerce is currently a minor source of revenue for New Luxury creators, but it is growing fast and contributing to sales and brand growth in many ways beyond direct sales.

Although a minor source of revenue for retailers, e-commerce is not an insignificant one. Williams-Sonoma, for example, had $133 million in Internet-based sales in 2001, or 6 percent of net revenues. Pottery Barn’s Internet sales grew from $49 million in the second quarter of 2001 to $83 million in the second quarter of 2002, an increase of 70 percent. The American Girl business has a particularly computer-literate customer base. Over 70 percent of its customers have Internet access, well above the 55 percent penetration of the whole US population.

Americangirl.com receives over 115 million hits per month, and Web site sales are estimated at $55 million, or about 15 percent of total revenue.

New Luxury creators and retailers understand, however, that the Web is about Connecting and Questing as well as sales. Americangirl. com is rich with content, offering games, polls, e-cards, activity ideas, trivia quizzes, and an advice column for girls. BMW created tremendous buzz with its BMWFilms, action shorts directed by and starring world-class talents and featuring BMW cars. The first round of films was viewed more than 14 million times. Two million people registered on the Web site, 60 percent of whom opted to receive more information via e-mail. Ninety-four percent of registrants recommended the films to others, feeding into a viral campaign that seemed to encompass the world.

Influence of solo females. Our survey shows that solo working females are particularly active buyers of New Luxury goods. Young singles rocket in a relatively small number of categories, but divorced women told us they rocket in as many as thirty different categories. With the incidence of divorce continuing to rise, and with singles delaying marriage, the pool of solo females is likely to increase— along with their willingness to spend on goods that help mitigate the rigors of Connecting (or not Connecting) and the pain of divorce.

Seniors as heavy spenders. Seniors represent an enormous potential market that New Luxury goods creators have yet to fully tap. Not only is their number growing as Americans live longer (currently there are about 46 million people over the age of sixty), but they are generally healthier, more active, and more willing to spend on themselves than any previous generation. Our survey results show that seniors are spending on their children and grandchildren, but they are not neglecting themselves to do so; they are particularly big rocketers in packaged travel. There is an opportunity to better serve the senior travel market with clothing, luggage, health care products and services, food supplements, photo and electronic-imaging systems, travel planning and support services, and more.

Next-generation consumers: smarter and more sophisticated than ever. It is the “juniors,” aged six to eighteen, however, who represent the greatest potential for continuing and expanding the trading-up phenomenon. They are interested in learning, travel extensively, and are highly attuned to brands and products. They have become accustomed to the acceleration of the innovation cycle and are not as exhausted by it as their parents or as bewildered by it as their grandparents. Juniors take it for granted that styles are quickly replaced with new ones and that products should be constantly updated and improved. Unlike their elders, they have no memory of a time when products did not always deliver quality. They will have little, if any, patience for goods that are poorly made or don’t perform as promised. They surf the Web, communicate on many channels, and drive the definition and recognition of what is new.

Most important, juniors have come to expect and appreciate the emotional satisfaction they get from New Luxury goods. As many consumers told us, “It’s very hard, if not impossible, to go back” to lower-quality, undifferentiated, emotionally empty goods once you’ve experienced a New Luxury entry in the category. Americans never like to settle back, give up, and trade down unless they are absolutely forced to by world events or personal vicissitudes. Even when times are rough, they tell us, they continue to hold on to one or two New Luxury items they “just can’t live without.” Americans, including kids, always want to escalate to still higher levels of quality, taste, and aspiration.

The Demand Society: The Middle Market Takes Control

There is another important aspect of trading up in today’s society, beyond its speed and volume: the newfound power of the middle-market consumer. Traditional trading up might be described as a downward-flowing cascade of innovation. A luxury first appeared on the market in very limited quantities and at very high prices, available only to the rich. It might take years, even decades, for the luxury to become more widely available and for the price to come down to the point where the middle class could afford it. For example, that most ubiquitous commodity, coffee, began its career as a luxury item. The delights of the coffee bean were probably discovered in Ethiopia before the year 1000, but coffee did not reach Europe until around 1600. It gradually was transformed from a rare and expensive treat into a daily want and, at last, into a necessity of everyday life. In the late 1780s, during the run-up to the French Revolution, the ordinary people of Paris took to the streets to protest the high cost of what they believed were the necessities of life, including sugar and coffee. In our own time, cashmere was for years an expensive luxury, affordable only for the wealthy, with limited supply. With the opening of China, however, supply has increased, and the price of cashmere has dropped considerably. It is now possible to buy a woman’s cashmere sweater at Lands’ End for just over $100.

The point is that the consumer has traditionally had little control over the pace and timing of the downward cascade of luxury goods. The producer had the control because demand was high and often the supply of raw materials was limited. Besides, the producer often had no great desire to speed up the cascade, because he believed that exclusivity and high margins were the keys to success in luxury goods. But now, because the middle market has become so much more affluent and so much more sophisticated, the luxury producer need not give up those attractive margins in order to gain greater volume.

At the same time, producers of conventional goods are faced with the problem of overcapacity and oversupply. Makers of cars, appliances, clothing, computers, and a dozen other types of goods have become so highly skilled and productive, and so used to selling in huge volumes, that they are making more of their products than consumers want or can buy.

Of course, businesses have been making more goods than American consumers strictly “need” for at least a century. That’s what marketing is for—to help create new wants for the consumer. But the “want-creation” industry has hit the wall. Because of all the factors we’ve discussed, businesses find that advertising, in particular, has lost much of its ability to persuade consumers to buy goods they don’t really want. Consumers know too much about product differences and availability, thanks to the proliferation of information available everywhere, especially on the Internet; they have too much choice; and they are too sophisticated about their own emotional needs to settle for mediocre goods.

Suddenly, the middle-market consumer has real control.

It is a control that is very different from the nominal control expressed in the traditional sales bromides—“The customer is always right” and “We don’t exist without the customer” and “Our major concern is customer satisfaction.” Today’s middle-market consumers are active participants in the creation of the goods they want. They don’t have to wait for the cascade to reach them; they can demand it because they have the power to buy, the knowledge to select, and the option to choose. They don’t really need anything, so they are hardly at the mercy of the producer.

We have said that trading up is a historic alignment of consumer needs and business capabilities. It may be more than that—it may represent a power shift from the producer to the consumer, a new dominance of the demand side over the supply side. That will make New Luxury goods all the more important in the years to come, since they are harder to create than conventional goods and therefore harder to copy. And they have the great advantage of providing emotional satisfaction, which is the key benefit that today’s consumer is seeking.

For Americans in the foreseeable future, the call is “excelsior”— ever higher—and that is what trading up is all about.

A Work Plan

To successfully seize the trading-up opportunity, companies must follow a work plan for conceptualizing, developing, and launching a New Luxury business.

But even before developing a work plan, there must be an impetus—a driving force and catalyzing energy to create something new. In many of the New Luxury companies we have studied, the impetus comes from an exceptional individual who discovers a business purpose in a personal experience. Some, like Pleasant Rowland, are extremely dissatisfied with the product offerings they find on the market. Some, like Ely Callaway, are driven by a passion and instinct for a category. Often, the impetus has a deeply personal and emotional basis. Gordon Segal wanted to live a life of European style and saw Crate and Barrel as a way to do so. Sometimes there is even a dramatic turning point, an Aha! moment, that is later seen to be the beginning of the business—such as Robert Mondavi’s violent break with his family.

These entrepreneurs provide instructive models for others who would like to begin a New Luxury business, not in the particulars of their lives, but in the common patterns of how they achieved their successes. From other stories, however, we know that successful New Luxury goods can be created by large companies and category incumbents that are not driven by an extraordinary leader or entrepreneur on a personal mission. BMW, Whirlpool, Panera Bread, Victoria’s Secret—these companies have created New Luxury goods within their established organizations, often going back to their roots for inspiration.

Established companies still need an impetus to get started, however, and it often comes from a competitive threat or the inspired thinking of a manager who is able to think like an entrepreneur. BMW was threatened by the introduction of Lexus and Infiniti into the luxury car market, and it was its response to the threat—a much sharper positioning as a performance brand and a relentless focus on driving excitement—that made it such a potent New Luxury brand and such a successful company. Whirlpool, too, was sufficiently threatened by the success of Maytag’s Neptune to bring its own front-loading machine, Duet, to the market. Ronald Shaich built Panera Bread through inspired thinking—he was able to see the potential of the Saint Louis Bread Company concept and had the guts to martial all his company’s resources behind it. Leslie Wexner, a serial entrepreneur who had already built a corporate empire, saw the potential for a whole new business in a tiny lingerie shop.

As good as these leaders and entrepreneurs are at creating New Luxury businesses, they are not always able to articulate exactly how they did it. The process, as they describe it, sounds almost haphazard. “I pieced things together,” says Wexner. Some of them spend years thinking about their idea and trying out early iterations. Ely Callaway bought Hickory Stick USA in 1982 but didn’t launch the revolutionary Big Bertha driver until 1991. Ronald Shaich spent months visiting bakery-cafés; it took him almost a year to sell his concept to the board of directors. Jim Koch of The Boston Beer Company had his idea for the “best beer brewed in America” in his pocket for at least five years before he made the leap. But once they take the plunge, the business can develop with amazing speed. Pleasant Rowland (American Girl), Jim Koch (Boston Beer), Edward Phillips (Belvedere vodka), Ely Callaway (Callaway Golf ), and Joe Foster (Whirlpool Duet) went from nothing, or tiny operations, to success with extraordinary speed.

Such success stories may make the process look easier than it is. We can assure you, however, that the billionaires and multimillionaires who have capitalized on New Luxury earned their net worth. This new form of competition generally benefits from first-mover advantage and often requires the outlay of substantial capital for equipment, inventory, trial generation, product improvement, and infrastructure. Winners invest in research and development that delivers technical advantages and in market surveillance that keeps them current, competitively aware, authentic, and fresh. They pay for their new product launches ahead of their success. They often have to go back to the drawing board after initial market reaction to regroup and reignite their enthusiasm.

Although the process is never easy or entirely predictable, it can be understood, defined, planned, and managed. It need not be so meandering as the path followed by some of the leaders profiled in this book, nor does it have to be years in the making. In our work with clients, our approach involves three steps: Vision, Translation, and Execution. In the Vision phase, the idea is developed and defined. In Translation, a product or service prototype is created. Execution is about launching the product and capturing the market, then refining the concept, expanding the business, and establishing an economic formula that pays off.

Vision: Knowing Where and How to Look

To create a vision of a new product or business does not require that the leader undergo an emotional epiphany or a tremendous revelation. At the beginning, the vision may be a simple idea about a market or a group of consumers. Ronald Shaich liked the way people sat around the Saint Louis Bread Company cafés, and he thought there was something important about it. Leslie Wexner, who had lots of experience with apparel, thought that lingerie had a much higher emotional content than plain underwear but that it wasn’t being addressed by any product on the market. Ely Callaway likewise knew that the recreational golfer needed help, and fast. Such perceptions usually precede the idea for a specific product.

But how do creators get these ideas? They usually come from looking carefully and extensively into a category and gaining understanding, knowledge, and insight about it. First you must decide where to look—choosing a category or segment with New Luxury potential. Such categories tend to have one or more of the following characteristics:

Goods are stale and undifferentiated. Any category where the products are similar and no one of them offers a differentiated ladder of benefits represents an opportunity for a New Luxury entrant. This was the case with wine before Mondavi, Callaway, and Jackson; it was true of refrigerators before Sub-Zero; it was true of frozen pizza before DiGiorno. Today, prepared vegetables, corporate hotels, and airlines are categories where the majority of the players look and sound alike.

Goods lack emotional engagement. New Luxury goods are always based on emotional engagement. A category where existing goods do not connect with consumer emotions—or produce negative ones—might be a New Luxury candidate. Consumers knew that there was a lot of emotion involved in doing laundry, but the makers of washer-dryers hadn’t made the connection. When market research says the consumer is “bored” or the category “lacks salience,” you may be looking at an opportunity.

Compromises to be broken. Established companies often get stuck in the rut of compromise. In quick-service restaurants, the compromise was between speed and quality—it was believed that you couldn’t deliver a meal quickly and also customize it and use non-standardized ingredients. Panera Bread, Pret A Manger, and Chipotle have broken that compromise. Trader Joe’s, for all its success, has been unable to break the compromise that remains in the grocery business—stocking private-label specialty items and mass-market goods such as eggs, produce, national-brand cereal, milk, and personal-care and home-cleaning products.

Cost could be put in, rather than taken out. We have seen that consumers will pay a substantial premium for goods that deliver on the ladder of benefits and that New Luxury leaders often make a substantial investment in development, raw materials, and production to ensure that their goods deliver technical and functional differences. Over the past decade, the focus for many companies has been on taking cost out of their operations. As a result, their products can lose richness and excitement, as American luxury cars have.

Stanley Marcus, who headed Neiman Marcus for many years, said that the same was true of the fur coat business in the late 1930s. “Most of my competitors were always trying to knock off a few dollars on every coat they purchased,” he wrote in his autobiography, Minding the Store. “I followed the opposite strategy—I offered to pay our manufacturers extra if they could make our garments finer.” By putting cost in, Neiman Marcus offered better coats with genuine differences for which it could charge a premium. Similarly, an increased cost of just 5 percent for raw materials in pet food can translate into a 30 percent price premium.

Many categories have experienced “value engineering.” Too often that actually means reducing quality or cutting corners in ingredients or packaging. Such value-engineered products, with their downgraded quality, are potential targets for New Luxury competition.

Gaps between mass and class. When there is a large price gap between the middle-market offering and the superpremium product, there is an opportunity for creating a masstige New Luxury product or service. In our work with a number of financial services institutions, for example, we know that consumers are dissatisfied with the undifferentiated products and services offered to the “little guy,” as compared to the customized “private banking” services they believe that the rich customers enjoy. Just as Jess Jackson described the wine business, there is a gap in financial services that’s so big “you could drive a truck through it.”

Craft businesses with middle-market commercial potential. Many New Luxury creators start with a craft business and find a way to standardize the offering enough to produce it on a much larger scale. Starbucks is a scaled-up version of an Italian café that retains some aspects of the original (the barista, custom drinks, and variations in interior design) but has a standardized approach and centralized organization that enables fast build-out, huge volume, and consistent quality.

Technical barriers. In many categories, there is a better product waiting to be introduced but no producer willing to invest the resources and energy, or take the risk, to overcome the difficulties of mastering the process. There were large-head golf clubs on the market long before Callaway introduced the Big Bertha, but no one had figured out how to make them deliver the desired end result— an occasional 275-yard drive for the weekend golfer.

Just as important as knowing where to look is learning how to look for opportunities within a category.

Patterning. Patterning is a way of gaining insight into and understanding of a category, and it is very different from conducting traditional consumer or market research—such as polling, focus groups, interviews, and the like—or gathering conventional competitive intelligence. Rather than looking at the category as it currently exists, patterning is a process of looking for elements and trends within the category itself, and in other categories, that can provide insight into what the category could become.

For established players, this means paying less attention to the nearest competitor and looking more broadly at the entire market by examining every competitive company, including high-end providers, niche brands, companies in other cultures, and start-ups. What are they doing that’s working? What is getting in their way of being more profitable and growing faster? It means gathering lots of data—both qualitative and quantitative—about the products on the market, how they are used, how they might be used, who is using them and why.

Patterning is also about looking for businesses in other categories that have succeeded by responding to elements and trends similar to those in one’s own category. Ronald Shaich believed that he could pattern aspects of Starbucks in creating Panera Bread— especially focusing sharply on a central, emotionally engaging element and building an appealing environment to surround it. Starbucks built its business around coffee; Panera did it around bread. Wexner’s search for patterns regularly takes him to fashion markets around the world—from Paris to London to Rio to Hong Kong to South Bend. It is a quest that involves discipline, science, and a kind of “business anthropology.”

Idea seeking in different geographies and cultures. The world is full of ideas waiting to be developed, borrowed, copied, adapted, or improved upon. Many New Luxury goods are adaptations of ideas from other cultures, particularly those of European countries. Crate and Barrel, Starbucks, Samuel Adams, Kendall-Jackson, Whirlpool Duet—all these brands have roots in western European ideas, primarily because that is where Americans have visited the most in the past three decades.

With the increase in travel to Asia, Africa, South America, Russia, and eastern Europe, interest in ideas and styles of those countries will certainly grow. As a creator in search of an idea, you can simply take a trip to an unfamiliar geography or culture. Wander the streets. Go to the markets. Talk to the people. Buy the goods. Eat in local restaurants and stay at local hotels. Watch, ask questions, try things, take goods home, and show them to your friends. Find a way to translate the foreign experience into a version that suits American tastes and behaviors.

Social research. New Luxury creators tend to be people who are interested in the world. They want to understand how society is changing and how people are thinking. They read widely and keep an eye on the popular media. What are Oprah Winfrey and Martha Stewart talking about? What are the magazines covering? What television shows are hot? They watch global trends and local customs and try to make connections between their observations and information and the role of goods and services in our society and in the lives of individuals.

What, for example, does the rise in the average square footage of the American house mean? For Boston University, it meant that its incoming students were extremely dissatisfied with the size and amenities of their dormitory rooms—they were used to having their

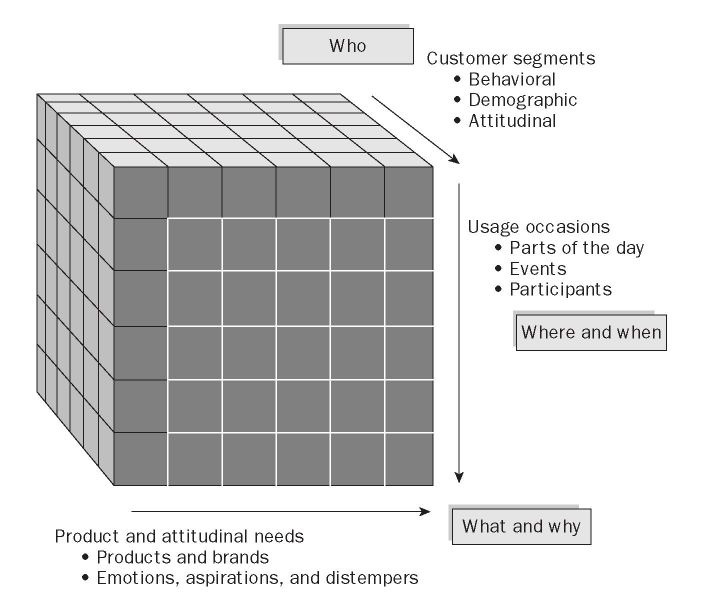

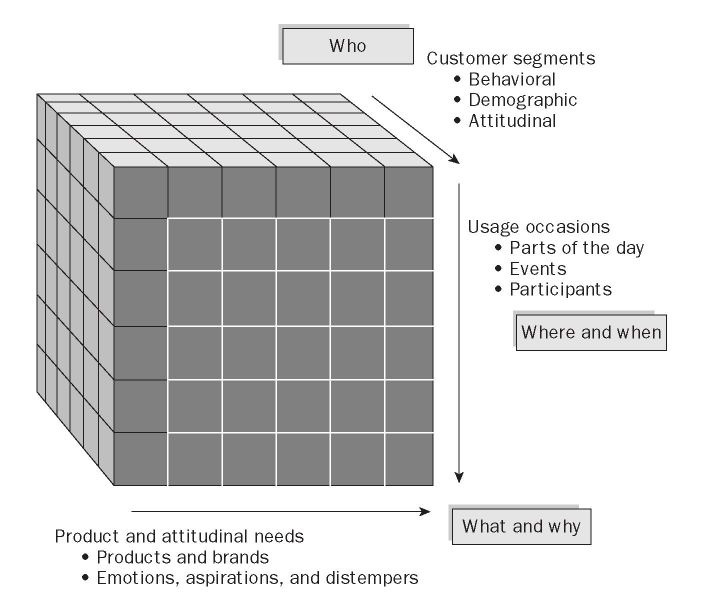

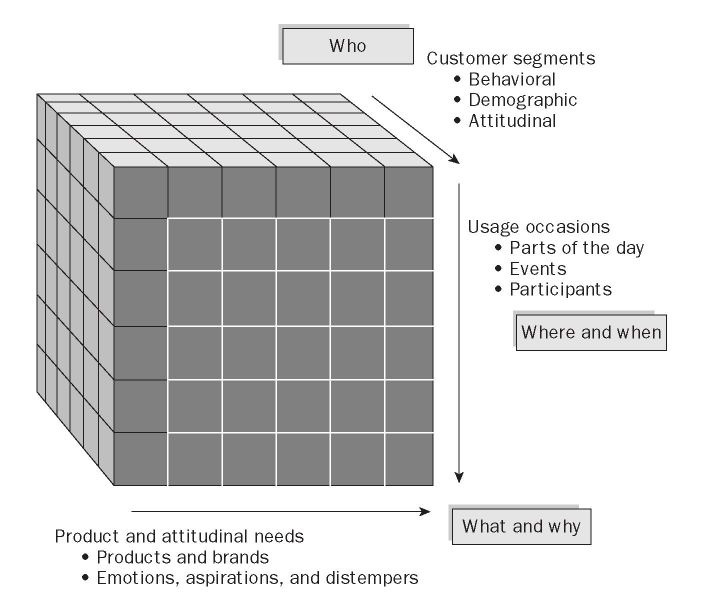

The cube is a tool that helps find “white spaces” where opportunity might lie.

own large rooms with a television, phone, and high-speed Internet connection. The university has developed new dormitories, offering single rooms with private baths and is charging, and getting, a premium for them.

Category analysis and the cube. It’s important to create a detailed picture of how the category currently appears, using data about trends in mix, growth rate by channel, real price trends, share and profit by segment, consumers, patterns of success by competitors, and a global comparison of the category.

The consumer segmentation cube is a way of expressing the current market by showing the intersection of three elements: the various types of customers, the “usage occasions” (where and when the goods could or might be used), and the attributes of available products. By bringing this information together, you can see the “white spaces”—combinations of customer segments, usage occasions, and product attributes that are empty and represent opportunities for development. The cube can open your eyes to clearly defined but underserved targets, and suggest cues about compelling product benefits and usage occasions.

Market sizing. During this phase, it’s important to determine how big the potential market might be. We use a market-sizing device we call the “consumption function” to break out category consumption and define the premium market. In pet food, for example, the consumption function is: millions of US households × percentage of households with pets × pounds per year per household × price per pound.

As we size the market, we work with consumers to determine what features would justify a premium price. In pet food, for example, we offer them a series of phrases, including “nutritionally complete and balanced,” “a perfect blend of taste and nutrition,” “scientifically researched and tested,” “appetizing aroma,” “helps my dog maintain proper weight,” and “makes me feel I’m doing the best thing for my dog.” Consumers prioritize and detail the product’s requirements. They also tell us a great deal about their wish lists and exquisitely describe—often with anger—the compromises and disappointments they have experienced with pet foods.

At the end of the Vision phase, you should be able to identify a small number of opportunities that could deliver on the ladder of differences, redraw the demand curve, and transform the category. The opportunities should be tightly defined. You should know whom you want to reach, the behavior you want from them, and how you will connect with them.

Translation: Moving from the Abstract to the Tangible

The Translation phase is about distilling, organizing, and interpreting the information and ideas gathered during the Vision phase and creating a concept for the product and business. The emotional space is defined during Visioning; Translation is about putting together and testing the technical and functional benefits to support the vision.

Concept articulation. This may involve the creation of a white paper—an extensive written description of the concept—but it should always be refined into a clear, easy-to-remember, highly distinct phrase or idea. For Victoria’s Secret it was “2/7ths.” We learned that young, single women were willing to wear uncomfortable but sexy lingerie for Friday and Saturday night social encounters—two nights out of seven. But even loyal users of glamorous lingerie turned to functional underwear during weekdays—the 5/7ths. Leslie Wexner wanted to create lingerie that was sexy and comfortable for the consumer to wear for those days as well. For Ely Callaway, it was “the perfect shot once a round”—he wanted to develop and market products that would enable golfers to get more enjoyment out of their round of golf. For each golfer, no matter how modest his skill, the club provided a tool for advanced play.

Rapid prototyping. The New Luxury winners develop prototypes quickly and take them into the field for testing with real users and, especially, expert users. Ninety percent of the concept testing we have seen, when done without working prototypes, is a waste of money and time. Consumers are not able to envision the final product; they tend to be too skeptical or overly enthusiastic. In the early stages of development of her American Girl dolls, Pleasant Rowland hired a marketing manager who suggested that she test the concept with a focus group of mothers. The focus group leader orally described the concept to the mothers, and they immediately and unanimously hated it. Then the leader showed the group a prototype doll along with a sample book and accessories, and the mothers changed their minds completely. It was a lesson that Rowland did not forget: “Success isn’t in the concept,” she said. “It’s in the execution.”

This does not mean that consumers do not have ideas for better goods and services. They should not be expected to define the product itself, however, but rather how they want to feel when interacting with the category. Lisa, a thirty-two-year-old mother living in Newton, Massachusetts, complained that “banks don’t treat me with respect. My husband and I are educated. But they never ask us, ‘Are you happy?’ ” She then described her vision of a satisfying relationship with a bank that led to the development of an important building block of a new premium financial services package. Your consumers can tell you about what they want, need, wish for, and only dream about. You will need to help them translate their phrases and nuances of feelings into a big, and workable, idea. It is then up to you to provide the big solution that beams sunshine on their faces.

Input and advice from expert users. Consumers value authenticity and genuineness in New Luxury goods, and they seek the validation of recognized experts and authorities in the category. Viking Range built its reputation by getting expert and professional chefs involved in the testing and refinement of the prototypes. Belvedere vodka enlisted professional bartenders to taste and comment on various distillations and flavors. BMW tests its new technologies on racing versions of its cars and by creating special M-Series models that showcase advanced features.

Value chain definition and scalability planning. The scale-up plan is another key consideration during Translation. It is one thing to deliver prototypes to a small number of expert consumers, but quite another to produce in quantity while retaining the artisanal features and quality—and to do so with speed and consistency. Once the benefit ladder is perfected, the challenge is to determine how to deliver it through “mass-artisanal” production without compromising the quality of the technical features or the integrity of the design.

During the Translation phase, Panera Bread’s professional bakers spent hours working in the kitchen and visiting bakeries across the country, experimenting with doughs and sampling different recipes as they worked to perfect new types of artisan breads. Equally important—and perhaps more complex—was the company’s ability to organize a delivery system that would enable Panera Bread bakery-cafés across the country to provide these artisan breads, freshly baked and with consistent high quality, to customers every day. That’s why the dough for the signature sourdough bread is always made from the original “mother” bread and mixed at central commissaries—there can be absolutely no variation in the flavor, texture, and rising properties of this bread. The other artisan breads, however, are allowed to vary from store to store. This combination of the guaranteed consistency of the sourdough bread and the unpredictable but delightful variation in the artisan breads is an essential aspect of Panera Bread’s appeal. Consumers can take comfort in an old favorite, or they can Quest with a sandwich made with one of a dozen different breads.

Execution: From Rollout to Revisiting the Concept

During the Execution phase we take the concept to market. It involves test marketing, a public launch or rollout, and refining and building the concept.

Define and recruit talent. Prior to launch, it’s important to evaluate the talent that has helped to create and translate the vision and determine what new talent may be needed to launch and scale up the business. Chuck Williams relied heavily on outside expertise to expand his popular San Francisco shop into the catalog business. But to create the national chain of stores that Williams-Sonoma has become, a very different set of skills was required, and that is why Williams sold the company to Howard Lester, an entrepreneur with a track record for growing small businesses (Williams remained as merchant visionary). Building a talented team in the early years provides a powerful foundation for continued technical innovation: Teams drive long-term success; teams with a history of working together and creating success drive speed.

Leverage experts. Leveraging the experts, connoisseurs, aficionados, and enthusiasts is the single best way—and is often the least expensive way—to refine early versions of the product, as well as to seed the user group. This group will tell you when your product has hit on the most compelling benefits ladder. In blind and labeled trials, the product should be able to achieve a ninety-to-ten win ratio among target consumers. That is the sign of a product that delivers real advantage. New Luxury winners are authentic and, therefore, credible and authoritative to the category experts.

Experts also provide a critical resource to leverage during the launch. There are many ways to do this: communicating regularly with early users, building customer advisory panels, sampling and conducting trials to provide free goods to high-profile users, and generally catering to the needs of this influential group—your future apostles.

Launch. Experts play a key role in the launch phase. New Luxury marketers know that word of mouth is more effective than advertising—and significantly less expensive. Increased fragmentation among formats, consumers, and behavior has led to diminishing returns on mass media advertising: The cost is up, but reach and depth are down. This is an unattractive prospect for any marketer, but especially for a fledgling New Luxury entrant.

Many New Luxury winners have successfully launched their products by creating an “underground buzz”—whether by design or by good fortune. The 10-50 rule drives most New Luxury launches: 10 percent of consumers deliver 50 percent or more of volume. The early users spread the word and the product can take off. (Pleasant Rowland called it “word-of-mother marketing.”) Red Bull, a premium energy drink, spent $4 million to $5 million on a launch that involved sampling among sixteen to twenty-nine-year-olds—at health clubs by day, and dance clubs by night. As word of mouth built, volume rose. Then the company began promotional spending—at carefully selected music and sporting events—but only in proportion to sales. The resulting increased volume enabled the company to work with a stronger distributor and begin radio advertising, and finally, to go “mainstream” with television and trade advertising.

Launch checklist. Before you launch, it is wise to evaluate the product or service by asking a series of questions about it:

Is it aspirational? Have test users become emotionally engaged with it? What is its primary emotional space? What is its secondary emotional space? Is it differentiated, pleasing to use, and a beautiful solution to a vexing problem? Can you imagine your consumer saying, “Thank you for creating this”?

Is it unique? Are there other products or services on the market that are similar? Are its technical features truly different? Does it deliver genuine performance differences?

Will it be the first in the market? Are you sure? If not, what genuine differences does it offer from those products that are already available?

Who is the core consumer? Can you describe the heavy users in detail? Have you met and talked with any of them? Have you visited their homes and workplaces and used the product with them? Do they crave it? Does it fit tightly into their lives?

Is it authentic? Do the technical differences contribute to performance benefits, or are they merely “cool features” or, worse, meaningless “bells and whistles”?

Is it authoritative and expert? How have respected experts in the category responded to the product? Have they tried it? Have they helped develop it?

Is it extendable through segmentation? Who else beside the core consumer might be interested? What other uses or situations might it be extended to?

Is it supported by a synchronized and informing business system? Do you have more than a strong concept and an exciting prototype? Do you have an organization in place that can manage the scaleup of production, expand distribution, and continue to deliver innovation?

Does it deliver on the ladder of benefits? Is it technically strong but weak on emotional engagement? Does it trade on emotion but not deliver on performance?

Do you have the next generation of innovation in process now? The fashion cycle is collapsing, and many New Luxury goods must be considered as fashion—even as the current product is being launched, the next iteration should be in the prototype phase.

Have you lined up influencers to seed usage? Who is going to speak up for the product? Who will tell their friends about it? Where and when will they be seen?

And one final question: How do you feel about the product? Do you love it? Do you enjoy using it yourself ? Do you believe the world needs it? Do you want people to embrace it? Are you also dissatisfied with it and do you want to make it even better? Can you imagine spending the next ten years of your life working with it, promoting it, refining it, building it into a respected New Luxury brand?

If you answered yes to all the above, we want to buy whatever it is you’re selling.