I’ve been on two wheels for over forty years. My earliest bikes were Indians—Chiefs and a Warrior. I also rode BSAs, Triumphs, and other assorted British bikes including a really beautiful Velocette Venom Veeline Clubman. But now as I enter the twilight of my riding years, I find myself sticking ever more tightly to my Harley—a nearly stock 1986 FXRT. I often wonder why I am so attached to my Harley; why I prefer to keep it rather than trading it for a smoother, faster, more modern machine from Japan or Germany. Why am I so attached to a Harley?

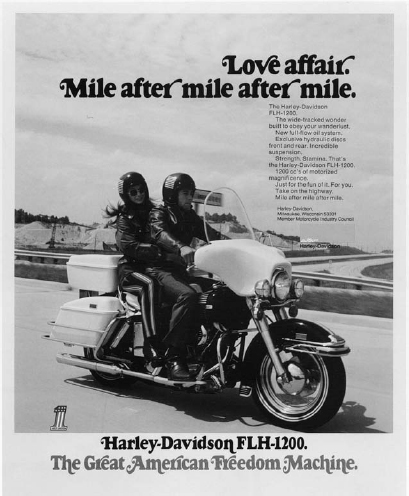

A possible answer is suggested by some Harley advertising. In the 1970s, the Motor Company inaugurated a new advertising campaign. The Harley-Davidson motorcycle was to be known as “The Great American Freedom Machine.” The flag-waving carried on as usual, but with the added link to “freedom.” The effects of the campaign linger. We are still given the opportunity to purchase belt buckles, wall clocks, tee shirts, beer mugs, cigarette lighters, and other assorted consumer goods proclaiming the intimate connection between Harleys and freedom. The advertising motto is suggestive, but the philosopher may be puzzled. What kind of freedom is being invoked here? And what is the alleged connection to Harleys? Could this explain my attachment to my FXRT? Do I ride a Harley because it makes me more free?

Freedom, broadly construed, is fundamentally a matter of absence of restriction, interference, or constraint. You are completely free to do something if absolutely nothing prevents you from doing it. Limitations on your freedom come about when something interferes or restricts or puts extra costs on doing that thing. Those who tend to focus on political matters may think of freedom as absence of legal or governmental restrictions and they may naturally be inclined to think that when a person has a lot of freedom, there are relatively few legal restrictions on his speech, religion, travel, associations, and other sorts of activity that sometimes are restricted by governmental interference. But there are many other sorts of freedom. We can distinguish among these sorts of freedom by focusing on the source of the restriction. Who, or what, is making it harder, or impossible, for me to engage in this action?

A person’s freedom might be limited by factors that are necessary and pervasive in nature. For example, suppose that the principle of universal causation is true, so that absolutely every event that occurs is caused by prior events. Nothing is genuinely “random.” Then every bit of every person’s behavior would be caused by prior events (and those events would be caused by events before them, and so on to the beginning of time). In a sense then, everyone would be completely “unfree.” Your movements would be relevantly like the movements of a pushrod in a smoothly running Twin Cam 88B engine. And you would still be completely unfree in this way even if you steadily felt as if you could choose to behave in a different manner. The feeling of freedom, in this case, would be some sort of delusion—itself the product of earlier causes going back to times before you were born.

Some philosophers believe that pervasive metaphysical “unfreedom” would occur if there were a God who has had foreknowledge of every bit of human behavior from the moment of creation. They think divine foreknowledge would make it impossible for anyone ever to do anything other than what one in fact does. After all (they reason) if God already knew millions of years ago that I would neglect to wear my helmet today, then it is in a way impossible for me to put it on. How can I put it on, if He already knew millions of years ago that I wouldn’t? Surely it is too late now for me to bring it about that He didn’t know millions of years ago that I wouldn’t wear my helmet.

Another alleged possible source of pervasive unfreedom would be “fate.” Suppose it was already true millions of years ago that I would neglect to wear my helmet today. I can’t change the past. So (some infer) it’s impossible for me to wear my helmet today. If we are constrained in any of these necessary and pervasive ways, then each of us is metaphysically unfree. If there are no such metaphysical constraints on some person’s performance of some action, then that person is metaphysically free to perform the action.

It should be obvious that if people do have this metaphysical freedom, then they have it whether they are cruising down the highway on a Road King or in a Toyota Camry LS. A person’s choice of vehicle could not seriously be thought to have any bearing on the question whether she has metaphysical freedom. Indeed, it seems likely that if anyone is metaphysically free, then everyone is metaphysically free. Metaphysical freedom would be part of the human condition in general if it were part of anyone’s condition. Surely, when the advertisers at the Motor Company decided to invoke the phrase “The Great American Freedom Machine,” they did not mean to suggest that those who were formerly constrained by chains of causal determinism or divine foreknowledge could break those chains by buying a Fat Boy. If they were chained by metaphysical necessity before purchasing the bike, they would be so chained afterwards.

A much less sweeping sort of restriction on action might be imposed by governments and legislation. For example, suppose that I live in a state where there are laws prohibiting the use of straight pipes. Then I am not legally free to use straight pipes. Legislative restrictions on freedom are not quite as overpowering as metaphysical restrictions. If you are metaphysically unfree to do something, then you simply cannot do it. But you can violate the law. You can install and use straight pipes even if there is a law against it. But then you will be subject to various legal penalties, such as a fine or jail time. The restrictions in this case appear in the form of extra costs or burdens associated with performing some sort of action.

Let’s say that you are completely legally free to do something if there are absolutely no governmental, regulatory, or legal constraints on your doing it. To the extent that there are legal restrictions on your behavior, your level of legal freedom is reduced.

If a person lives in a place where there is a government in charge, then his legal freedom cannot be absolute. Consider my neighbors in New Hampshire. Their license plates proudly proclaim LIVE FREE OR DIE, yet even they cannot claim complete legal freedom. They must get their cars inspected and keep right except when passing. They are required by law to have the freedom-proclaiming plates clearly visible and illuminated on the backs of their cars. They are not completely legally free. A person’s legal freedom is greater as the restrictions and requirements are less severe.

Over the vast range of interesting activities, choosing a Harley instead of a Camry has no impact at all on one’s level of legal freedom. Harley riders and Camry drivers in the United States are equally legally free with respect to virtually every sort of behavior. Assuming that they are of equal age and citizenship, and that neither is a convicted felon, they are free to vote, to run for office, to engage in peaceful protest, to assemble with others of like mind, and to move about the country as they see fit. Neither of them is legally free to exceed the speed limit or to drive without a license. Neither of them is free to make threatening remarks about the President.

One would have to search carefully for any difference in levels of legal freedom between a Harley rider and a Camry driver. However, it seems that if we look closely enough, we may find that there are some microscopic differences. In most states Harley riders enjoy slightly less legal freedom than drivers of Toyota Camrys. The mere fact that a person chooses to ride a motorcycle subjects him to extra governmental interference. In Massachusetts (where I live) anyone who wants to operate a motor vehicle on a public road must first have a regular driver’s license. We all uniformly face that limitation on our freedom. But those who want to ride a motorcycle face even further restrictions. We must take extra tests, both on the road and in the classroom. And, worst of all, we are required to wear approved helmets.

I recognize, of course, that we are legally free to ride our bikes without seatbelts. That is a restriction that limits the freedom of car drivers, but one that we evade. Nevertheless, in spite of some minor differences, on balance it seems to me that there is no basis for saying that the Harley rider is any more legally free than the Camry driver.

Some restrictions on action have nothing to do with laws, and nothing to do with universal causation or any other pervasive metaphysical factor. Such restrictions might arise from some mere matter of personal circumstances. For example, suppose you live on an isolated farm. You have no car, truck, or motorcycle. There is no bus station nearby. You can’t afford to call a cab. If you want to go anywhere, you will have to walk, but the nearest interesting city is many miles away. Then your freedom to travel is restricted, even if you have free will and there is no law against traveling. The problem is the mere circumstance of not having access to a suitable vehicle. Let’s use the term “circumstantial freedom” to refer to the sort of freedom that is restricted in this way by circumstances.

In this situation, a Harley might be a “freedom machine.” If you could get your hands on a bike, you could toss some gear into the saddlebags and cruise away into the sunset, looking for adventure. The Harley would open up some options that would otherwise have remained closed.

Thus, it might seem that the Harley has earned the right to be called “The Great American Freedom Machine.”

But there is a serious problem with this line of thought. We seem to be comparing the case in which you have no means of transportation with the case in which you have a Harley. Of course your freedom to travel is greater in the second case. But the fact that the vehicle in this case is a Harley is irrelevant. Your freedom to travel would be similarly increased if you managed to get your hands on an Indian, or a flathead Ford, or a Toyota Camry. Any suitable vehicle would improve your situation freedom-of-travel-wise. So the example does not show that Harleys are freedom machines; it suggests that cars, trucks, motorcycles, or any other suitable vehicles are freedom machines.

In his dialogue Philebus, Plato (427–347 B.C.E.) compared the life of pleasure with the life of wisdom, trying to see which would be the better life. In the dialogue, Socrates lays down some ground rules for comparison: he says that to get a fair comparison you need to compare a life containing lots of pleasure but totally devoid of wisdom to a life containing lots of wisdom but totally devoid of pleasure. We should follow Socrates. We should compare a life containing just a Harley (and no other vehicle) to a life containing just a Toyota Camry LS (and no other vehicle). We should try to imagine the lives vividly and fairly, and we should try to determine whether either life is significantly freer than the other. Does possession of the Harley open up options that would be closed to the Camry driver? Or is it the other way round? Or are the two drivers pretty much on a par when it comes to freedom?

It’s hard to see how Harley ownership could have a significant effect on circumstantial freedom. Some small differences are obvious: if you don’t have a Harley, you are not free to walk into your garage, throw your leg over your Harley, and fire it up. So the Harley owner has freedom to do one thing that the Camry owner cannot do. But the Camry owner has an equal advantage with respect to another sort of action: he is free to walk into his garage, slide his butt into the front seat of his Camry, and fire it up. The Harley owner can’t do that. It seems to be a zero sum game. Whichever way you go, you win one, and you lose one.

Some people use the term “freedom machine” to refer to wheelchairs. This seems to me to make a lot of sense—especially if we think of the sort of freedom that involves the removal of circumstantial restrictions on actions. Without a wheelchair, a person with a physical disability may be restricted, or limited, in his movements. There are places he can’t go, or can go only with difficulty. But when he gets a suitable wheelchair, previously closed options open up. The number of interesting alternatives available to him increases. Nothing like this happens when a Camry driver trades in his car for a Sportster.

There’s no clear conception of freedom according to which riding a Harley will lead to an increase in someone’s actual level of freedom. But it’s still possible that there is some connection between Harleys and freedom. Maybe the idea is not that owning a Harley will make you more free. Maybe the idea is that owning a Harley will give you an opportunity to celebrate, or express, your freedom. As you cruise around the neighborhood with your straight pipes rumbling, you might in a way proclaim your freedom. Every ride could be construed as a sort of exclamation: “Look at me! I’m free! My activities are subject to fewer constraints than the activities of Camry drivers! Whoopie!”

Surely a person could do that. But in light of what we have already seen, this seems a bizarre way of expressing your freedom. After all, if you choose to ride a Harley, you will not be any more free in any identifiable way, and you will be slightly less free in some ways. Isn’t it somewhat paradoxical to express your freedom by doing something that is antithetical to your freedom? It seems as bizarre as celebrating your health by eating greasy french fries and sugarcoated donuts, or celebrating your happy marriage by running around with strange women (or strange men, as the case may be).

Many riders claim to get and enjoy the “feeling of freedom” while riding. Perhaps this is closer to the point of Harley’s motto. Maybe what they really mean is “Harley-Davidson: the Great American Feeling-of-Freedom Machine.”

But this idea is also problematic. The central problem, as I see it, is that it’s not clear that there is any such feeling. Let’s consider this.

Try to imagine the feeling of fatigue. If you are fatigued, and you reflect on how you feel, may notice certain typical and familiar (if hard to describe) sensations: minor aches and pains in some joints; weakness in some muscles; droopiness in the eyelids; an urge to take a nap. Similar things happen when you feel hot or cold, or bored or excited, or dizzy. There are certain sensations that you typically have when you are in these states. If X is some state or condition (fatigue, coldness, fear, etc.), then the feeling of X is the combination of sensations you typically have when you are in state or condition X.

But there is no typical set of sensations that goes along with being free. Suppose, for example, that you have been locked in a jail cell for a long time. Suppose that during the night, while you slept, someone unlocked the door. When you wake up in the morning, you would be free but you would feel nothing distinctive. Freedom itself has no “feel.”

Suppose you check the door and discover that it’s unlocked. Now you believe that you are free. (Note that the belief that you are free is not a feeling; it’s a belief.) Perhaps when you think you are free you have a special feeling of freedom, and maybe this special feeling of freedom is the one that allegedly makes Harley riding so wonderful.

Although I have studied my feelings while riding, I never felt anything that I would describe as “the feeling of freedom.” Vibration, yes. (I used to ride a Sportster.) Cold, yes. Heat, yes. Buffeting of wind, yes. But freedom, no. Talk about the “feeling of freedom” seems to me to be based on a failure to reflect with sufficient care upon one’s own psychological states. Perhaps the Harley advertisements have led us down the garden path to the point where we misdescribe our own experience.

Often when I’m riding, I feel happy. I may have a feeling of exhilaration. I’m glad to be out on my bike. But feelings of happiness or exhilaration should not be confused with the feeling of freedom. I wonder if riders who claim to experience “the feeling of freedom” in fact have an experience that contains not a feeling, but rather a belief about freedom. Maybe what they experience is the combination of a feeling of happiness with a belief—the belief that they are free; the belief that they can “do anything” while riding. How paradoxical! They are in fact a little bit less free than they would have been if they had chosen a Camry; there is slightly less that they can do. They can’t easily change the track on their current CD; they can’t comfortably sip a cup of coffee at 75 m.p.h.; they can’t fiddle with the controls on their AC. They could do these things if they were driving a Camry. Yet they feel happy because they think they are more free.

If my hunch is right, this talk of Harleys as Feeling-of-Freedom Machines is thus doubly mistaken. First, the relevant feeling is not the feeling of freedom. It’s the feeling of happiness. Second, the associated belief—the belief that you are more free on your Harley—is probably false.

The old notion that we ride Harleys because Harleys are freedom machines simply won’t cut it. If taken as the view that riding a Harley will make you more free, it’s false. If taken as the view that riding a Harley will give you the feeling of freedom, then it’s unclear and dubious. Is there any such “feeling”? So there must be some other reason why we ride. We evidently give up some of our freedom in exchange for other goods. What are these goods?

Some say it’s the comradery. They join their local HOG chapter hoping to gain solidarity with a bunch of biker brothers. This seems like a pretty expensive and inconvenient way to get friends, especially if you really don’t enjoy riding all that much. Surely, if you are looking for friends, it would be more efficient and convenient just to post some personals. Personally, I don’t ride because of loneliness.

Perhaps in an earlier era, owning a Harley gave our grandfathers the opportunity to travel to distant places cheaply and efficiently. But the idea that travel by Harley is cheap and efficient in America in the twenty-first century is ludicrous. If you want to get someplace cheaply and efficiently, the Camry is the ticket—especially in cold and rainy weather. There are any number of Japanese motorcycles that will run circles around your Harley. So if you want to get there fast, you should get something more like a Suzuki GSXR 1300R.

Some say that the great thing about a Harley is that it gives you the chance to smell the roses. This much is true: when you pass through a neighborhood where there are a lot of roses, you may be able to smell them while riding a Harley. However, if the smell of roses turns you on, you can also get your turn-on in a Camry. Just press the button that opens the windows. (The Harley has a drawback not shared by the Camry: when you rumble through a neighborhood where there is a sewage treatment plant, you will be forced to smell the shit. You can’t close the windows on the Harley. Nor can you turn up the air conditioner. In this case the Camry has the edge.)

Some people get a lot of satisfaction from knowing that they can personally dismantle and reconstruct their vehicle with their own tools. They enjoy knowing that they understand what makes it work. In some cases they take great pride in knowing that they designed and built the machine on which they ride. If you want that, you might get it with an antique bike, or with a Ford 8n tractor, but not with a Harley of recent vintage, which is as incomprehensible as a Toyota.

My own view (and here I acknowledge that I am speaking only for myself) is that traveling on a Harley is just more fun and more exciting than going in a cage. I like the thrilling feeling when I dip into a nicely banked curve, and feel the power and ease of the bike as it leans until the footpeg begins ever so slightly to skim the pavement. I enjoy many sensory aspects of the experience: the sound of the exhaust, the feeling of the air and the engine, the look and smell of the bike. I also enjoy the excitement that comes when I sweep around a corner and discover a flock of turkeys in the road, or a moose standing there dumbfounded. That sort of thing may give you something to think about; something to remind you of the fact that you love life, and love being close to your machine, and love the thrill that comes from riding a bit closer to the edge.

Of course, I could get those pleasures on a Honda or a BMW. But I also take pleasure in knowing that my bike is the direct descendant of a long line of air-cooled V-twins going back through the Panheads, Shovelheads, Knuckleheads, and Flat Heads all the way back to the Model J and the 5D and then even further back to the (single cylinder) Silent Grey Fellow. My bike links me to a great tradition that started in a garage in Milwaukee more than a century ago, and I enjoy knowing that I am part of that tradition. These are all delightful experiences; they are some of my reasons for riding a Harley. They are pleasures you can’t get in a car or on any bike but a Harley. But they have nothing to do with freedom.

If you continue to believe that there is some connection between Harleys and freedom, then I encourage you to think more deeply. To say that riding a Harley makes you more free is to say that riding a Harley removes some restrictions or constraints on your choices of action. Can you identify the source of the restrictions precisely? Can you specify the forms of action that become available when you plunk down your $20,000 for the Harley? Perhaps you think riding your Harley gives you a feeling of freedom. Can you say precisely what this feeling feels like? Can you identify the part of your body in which you feel it? Are you certain it’s not just a belief combined with a feeling of exhilaration? If not, maybe you should agree with me that while you wouldn’t trade your Harley for a Camry, your preference has nothing to do with freedom.1

__________

1 Thanks to Elizabeth Feldman, Dick Godsey and Chris Heathwood for helpful criticism and suggestions.