Chapter 12

The Competition from Exchange-Traded Funds and Hedge Funds

We looked in the last two chapters at how funds are distributed to investors through the intermediary, direct, and retirement channels. Now we turn our attention to two of the toughest competitors faced by traditional mutual funds: exchange-traded funds—commonly called ETFs—and hedge funds. Both have been growing rapidly. We take a closer look in this chapter at how they are structured and why they have had so much appeal for investors.

This chapter reviews:

- Exchange-traded funds: their advantages and disadvantages, structure, operations, investment approach, and future

- Hedge funds: their advantages and disadvantages, strategies, investors, and regulation

EXCHANGE-TRADED FUNDS

Exchange-traded funds are hot! They’re the smart, new apps of the fund world. Need a low-cost fund based on the S&P 500? There are several ETFs that will work for you. Want to win big if the Dow Jones Industrial Average goes down? There are ETFs that will serve your purpose. How about an investment in bonds? Or are you interested in owning commodities like platinum, gold, and oil? Yes and yes. There are ETFs that match all your investment objectives, whether conservative or aggressive. And it seems as if new ETFs are being launched every day.

The recent growth of ETFs has been eye-catching, especially when compared to the overall growth in the fund industry. That hasn’t always been the case. The ETF industry grew slowly in the dozen years after the launch of the first ETF in 1992. (See “Of SuperTrusts, SPDRs, and WEBS” for more about the earliest ETFs.) At the end of 2004, there were only 152 ETFs from a handful of sponsors with just $228 billion in assets. In the mid-2000s, however, ETFs hit a tipping point, and growth took off. By the end of 2009, the industry had grown to more than $775 billion in assets with close to 800 funds from approximately 30 sponsors.1 Over a five-year time frame, ETFs had a compound annual growth rate of more than 27 percent. Growth in the mutual fund industry overall was only 7 percent in that same period.

OF SUPERTRUSTS, SPDRs, AND WEBS

Q: What was the first ETF in the United States?

Some students of industry history argue that it was the SuperTrust, which began trading on the American Stock Exchange in 1992. Developed by the principals of California investment firm Leland O’Brien Rubinstein, the SuperTrust responded to the need for an S&P 500 Index fund that traded on an exchange.2 It was a complex product designed for institutional investors, that never developed much of a following and was eventually liquidated.

That’s why most historians award the claim of “first” to another S&P 500 Index-based ETF—the Standard & Poor’s Depositary Receipts, abbreviated as SPDRs and pronounced like spiders. A streamlined version of the SuperTrust, the SPDRs trust was launched by the American Stock Exchange in 1993, and its underlying portfolio remains the largest ETF today. SPDRs is structured as a unit investment trust.

Looking for the first mutual fund–based ETFs? (We review the difference between the unit investment trust and mutual fund forms shortly.) Those are the WEBS—an appropriate complement to SPDRs—which were developed by former Leland O’Brien Rubinstein staff for Barclays Global Investors and Morgan Stanley in 1996. The Barclays WEBS grew into the largest family of ETFs in the world, now under the BlackRock iShares brand.

As you can see from Table 12.1, much of the growth in ETFs appears to have come at the expense of traditional index mutual funds. ETFs—which are usually passively managed themselves—are direct competitors for index funds. In 1998, index funds comprised $264 billion of fund industry assets, versus just $16 billion for passively managed ETFs. Even as late as 2005, index funds still had more than twice the assets of ETFs. But by the end of 2009, the $703 billion in index ETFs—which excludes $75 billion in commodity ETFs—was not far behind the $837 billion in index mutual funds. (Note that both ETFs and index funds captured share from actively managed funds, as we discussed in Chapter 4.) And now that actively managed ETFs have been introduced, as we’ll discuss shortly, some ETF advocates have begun to suggest that they may become more popular than traditional mutual funds over time.

TABLE 12.1 ETF and Mutual Fund Assets by Fund Type ($ billions)

Source: Investment Company Institute, 2010 Investment Company Fact Book.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Exchange-Traded Funds

Exchange-traded funds are similar to mutual funds in many ways, but they have a unique feature that sets them apart from mutual funds: their shares trade on a stock exchange or other market center. So, ETFs match mutual funds in providing investors an easy way to own a diversified basket of securities. But ETFs offer advantages compared to traditional mutual funds, specifically:

- Exchange-traded. Unlike mutual funds—whose shares are generally sold or redeemed only once a day after the close of business on the New York Stock Exchange—ETF shares can be bought and sold throughout the trading day.

- No investment minimum. ETFs can be bought in quantities as small as one share, while most mutual funds require a minimum investment of several thousand dollars to open an account.

- Lower expense structure. Since most ETFs are index funds, they have naturally lower management expenses. Also, because they are exchange-traded, their shareholder servicing costs are lower. As a result, many ETFs have lower expense ratios than mutual funds with comparable investment strategies.

- Broader set of investments. Some ETFs allow investors to have exposure to commodities and currencies, which traditional mutual funds are generally not permitted to own.

- Tax efficiency. ETFs are considered to be more tax-efficient than many mutual funds, meaning that they generate fewer taxable capital gains. We explain why this is the case later in this section.

On the other hand, traditional mutual funds have their advantages, too:

- Daily redemption at NAV. Mutual fund investors can go directly to the fund at the end of every business day to redeem their shares for the NAV. ETF investors must sell their shares on the stock exchange at the prevailing price—which can be different from NAV. While ETFs have mechanisms that keep prices and NAVs in line, they have not always been effective, as we’ll see.

- No trading commissions. While ETFs often have lower fund expenses than traditional mutual funds, investors in ETFs must normally pay brokerage commissions whenever they buy or sell shares—a cost that mutual fund owners do not incur.3

- Broader array of actively managed strategies. Most ETFs are passive index funds; actively managed ETFs are just beginning to be developed. As we’ll see shortly, many fund managers believe that ETFs are an inappropriate format for active strategies, so traditional funds may continue to be preferred by active managers.

So, What Is an Exchange-Traded Fund, Really?

The term exchange-traded fund has come to apply to a spectrum of exchange-traded instruments whose price depends on the value of an underlying investment portfolio. There are essentially three main types of ETFs, summarized in Table 12.2.

TABLE 12.2 Comparison of ETF Models

Type 1: Investment company ETFs. Most ETFs invest in securities such as stocks and bonds and are generally structured as open-end mutual funds or unit investment trusts. They are, therefore, regulated under the 1940 Act—though ETFs must ask the SEC for exemptions from some of the rules that apply to traditional funds. (See “Mother, May I?” for details.) As we’ve mentioned, most of these ETFs use index strategies, though actively managed ETFs were introduced in 2008.

MOTHER, MAY I?

Exemptive application and exemptive order are two terms that touch the very heart of exchange-traded funds. As we’ve learned, the 1940 Act contains detailed provisions regarding the structure, governance, and operations of funds—but ETFs don’t square well with these. Even some of the basics are challenges for ETFs under the 1940 Act. For example, as we’ve mentioned, shareholders of an ETF can’t redeem at NAV at the end of every business day.

To get relief from these ill-fitting regulations, an ETF and its sponsors must file an exemptive application with the SEC. After review and public comment—and, sometimes, even a public hearing on the merits of the application—the SEC issues a final exemptive order that spells out alternate rules for that ETF. The original ETF exemptive order took more than three years to negotiate, and while the process has gotten much faster, it still takes 12 to 18 months for a new ETF to get exemptive relief. (Compare that to just three to six months to set up a traditional mutual fund.) Why does it take so long? Because each exemptive order is individually negotiated. To speed things up, the SEC in 2008 proposed standardized rules that would eliminate the need for exemptive relief for many new ETFs. It’s not clear when or even if these rules will be adopted.

Type 2: Commodity ETFs. A small but growing number of ETFs own commodities, real estate, or currencies either directly or through the use of derivatives. These ETFs emerged in the mid-2000s and have blossomed along with interest in commodities, particularly precious metals such as gold. At the end of 2009, commodity ETFs accounted for 10 percent of total ETF assets, up from only 3.5 percent just two years earlier, according to the Investment Company Institute. Examples of commodity ETFs are the SPDR Gold Shares (ticker symbol GLD) and the iShares S&P GSCI Commodity Index Trust (ticker symbol GSG).

Because commodities, real property, and derivatives are legally difficult for 1940 Act funds to buy in any quantity, these ETFs are typically organized as partnerships, investment trusts, or grantor trusts that are not subject to the 1940 Act. As a result, commodity ETFs lack some of the investor protections enjoyed by mutual fund investors, including investors in traditional ETFs. For example, commodity ETFs do not usually have an independent board of directors watching out for shareholder interests. These ETFs, however, are still securities that must be registered with the SEC.

Type 3: Exchange-traded notes. Exchange-traded notes, or ETNs, are not funds at all. Rather, they are bonds, normally issued by a bank, with an investment return that’s tied to the performance of an index or basket of securities, commodities, or currencies.4 For example, the iPath EUR/USD Exchange Rate ETN pays a return based on changes in the exchange rate between the euro and the U.S. dollar. ETNs are a small but quickly growing part of the ETF market. Their assets totaled only $4.9 billion in April 2009 but had risen to over $11 billion at the end of April 2010, although that’s still just a tiny fraction of the ETF market in total.5

As with commodity ETFs, ETNs must register with the SEC but are not governed by the 1940 Act—meaning that owners do not enjoy the investor protections provided by that legislation. And ETNs involve an additional— and quite substantial—risk: the risk that the issuer goes bankrupt and is unable to make payments to ETN investors, known as credit risk.

How Do Exchange-Traded Funds Operate?

Let’s explore how ETFs operate from day to day. We’ll look at how ETFs create and redeem shares and how they manage subsequent market trading of their shares, focusing on investment company ETFs.

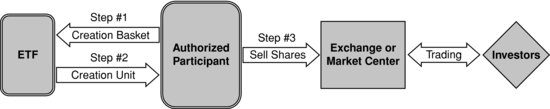

FIGURE 12.1 The Creation Process for ETF Shares

Creation and redemption of ETF shares. ETFs use a complex process to create and redeem their shares. As we’ve learned, in a traditional mutual fund, new shares are created whenever a shareholder makes an investment in the fund by buying fund shares in exchange for cash. Shareholders in traditional funds can reverse the process at any time, selling fund shares to receive cash equal to the NAV. In contrast, ETFs don’t deal directly with their shareholders; they instead create and redeem shares through an authorized participant, or AP, who is usually a large investor—often a hedge fund, market maker, or a broker-dealer—which has signed an agreement with the ETF. Creating ETF shares and distributing them in the market is a three-step process, illustrated in Figure 12.1:

- Step 1. The authorized participant assembles a creation basket, a portfolio of securities that exactly matches the portfolio of securities held by the ETF. To assist the AP, the ETF publishes a portfolio composition file that discloses the ETF’s holdings, at least once a day.

- Step 2. The AP delivers the creation basket to the ETF. In exchange, it receives a creation unit, which is a large batch of shares of the ETF— usually either 50,000 or 100,000 shares—based on the ETF’s NAV.

- Step 3. The AP breaks the creation unit down into smaller sets of shares and sells them in the public market, or the AP may decide to hold on to some or all of these shares.

Once the shares are on the market, they continue to trade between investors like any other stock.

The redemption process works like the creation process in reverse:

- The authorized participant assembles shares of the ETF, enough shares to equal a creation unit. Again, that’s usually either 50,000 or 100,000 shares.

- The AP delivers these shares—now known as a redemption unit—to the ETF. It receives in exchange a redemption basket of securities that reflects the portfolio composition file of the ETF.6

The creation and redemption process is a key advantage of the ETF model as compared to the traditional mutual fund structure. It allows ETFs to keep their trading costs very low, since it’s the authorized participant that does most of the buying and selling of portfolio securities.

The in-kind nature of the process helps ETFs minimize the capital gains that it passes through to its shareholders. An ETF need never sell its holdings to meet its obligations to redeeming shareholders; it simply transfers securities instead—together with any capital gains—to the AP, which may be a tax-exempt pension fund or an investor that has the ability to offset the gains with other transactions. Sound like a good deal? Some observers think that it’s too good a deal—and have urged changing the tax laws to put ETFs on the same tax footing as traditional mutual funds. Another potential cloud on the horizon is that it’s unclear whether APs will continue to be able to absorb all gains as the asset base continues to grow.

Exchange trading and the arbitrage process. As we’ve just learned, once ETF shares are created, they can trade freely on the stock exchange or in another market center. That means an investor can buy and sell them like regular stocks any time the markets are open. They’ll most likely trade on NYSE Arca, which dominates ETF exchange listings, having acquired the original home of ETF trading—the American Stock Exchange—in 2008.

The price of the ETF on the exchange will normally track very closely to the ETF’s NAV. That’s because arbitrageurs will create or redeem units if the ETF share price and its NAV get too far out of line. For example, if ETF shares are trading at a discount to or below its NAV, the arbitrageur will buy the ETF shares in the market to assemble a redemption unit, and then exchange the redemption unit for a basket of securities with a value equal to the ETF’s NAV. Since the NAV is higher than the ETF share price, the arbitrageur can make a quick profit by selling the securities. By automating both the monitoring and the creation-and-redemption process, arbitrageurs can take advantage of even small pricing discrepancies. Arbitrageurs are usually authorized participants because they have the inside track on the creation and redemption process.

It’s this arbitrage feature that distinguishes ETFs from closed-end funds. As we discussed in Chapter 2, both ETFs and closed-end funds trade on exchanges. But closed-end funds frequently trade at substantial discounts to NAV. That’s because they have a fixed number of shares, and there’s no mechanism to keep their market prices aligned with their NAVs. Only ETFs have the creation and redemption feature that helps to minimize premiums and discounts.

Because ETFs want their share price to closely track their asset value, they actively encourage this arbitrage by providing extensive information about portfolio holdings and their value. As we’ve noted, ETFs issue a portfolio composition file daily. The listing exchange also publishes an intraday indicative value, or IIV, at 15-second intervals throughout the trading day. The IIV is an estimated NAV that applies current market prices to the published portfolio.

TABLE 12.3 ETF Pricing (September 2009)

Source: Cerulli Associates, The Cerulli Report: Exchange-Traded Funds: Threat or Threatened? (2009).

Overall, the arbitrage system has worked fairly well at keeping ETF share prices and NAVs in line—but it’s not perfect. As you can see from Table 12.3, close to 60 percent of ETFs traded within 25 basis points of their NAV in September 2009—though one-quarter of ETFs experienced a meaningful discount. Discounts and premiums have been widening. And the arbitrage system has only just begun to be tested by market turmoil. (You can learn about a recent problem in “Gone in a Flash.”)

GONE IN A FLASH

Exchange-traded funds were particularly hard hit in the “flash crash” in the U.S. equities markets on May 6, 2010, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by 1,000 points in just a few minutes. More than 70 percent of the problematic trades that day were in ETFs. (These were trades that resulted in price declines of 60 percent or more during the very brief duration of the crash and that were to be subsequently canceled.) Some ETF prices collapsed to almost zero—almost certainly well below their estimated intraday NAVs.

What happened? At least three factors came into play after a fund manager electronically submitted a large sell order.7 First, investors tried to use ETFs to offset falling stock prices, either by selling an index ETF or buying an inverse ETF that rises in price when the market falls. Second, the rapid collapse in prices may have interfered with the arbitrage process, making it difficult to keep ETF prices and NAVs in line. Finally, communications among some market centers were suspended during the flash crash. Liquidity on NYSE Arca—the exchange on which most ETFs trade—appears to have been most affected by the communication cut-off.

How Do Exchange-Traded Funds Invest?

When determining their investment strategy, exchange-traded funds have a very important initial decision to make: whether to be index-based or actively managed.

Index ETFs. Most ETFs are passively managed, basing their portfolio composition on an index. The original ETFs were based on widely recognized indexes such as the S&P 500, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, or the Wilshire 5000. As ETFs have become more specialized, they have begun to focus on certain sectors, sometimes using custom indexes developed just for the ETF.

Index ETFs must decide what process they will use to track the target index. As we discussed in Chapter 5, index funds can use one of two portfolio management techniques: replication or sampling. In replication, a fund buys exactly the same securities as the index in exactly the same proportion. In sampling, a fund buys only a carefully selected subset of the index stocks, perhaps in conjunction with derivative securities.

Not all ETFs have a choice of technique, however. ETFs that are structured as unit investment trusts must use replication, while grantor trusts must hold an unchanging basket of securities. So it is that SPDRs—organized as a unit trust—must own all the stocks in the S&P 500, while its main competitor, the iShares S&P 500 Index Fund—organized as a mutual fund—can use sampling if it chooses. Sampling can introduce divergences from index performance known as tracking error. As a result of this and other factors, some ETFs have struggled to successfully track their index, as explained in “Whoops! I Missed the Target.”

WHOOPS! I MISSED THE TARGET

Tracking error: It’s an expression that can send chills down a portfolio manager’s spine. As we discussed in Chapter 5, minimizing tracking error is one of the major challenges of managing passive investment strategies. It’s becoming quite an issue for exchange-traded funds. A recent Morgan Stanley study found that the average index ETF deviated from its benchmark by a substantial 1.25 percent in 2009; most funds lagged their benchmark returns.8

The increased use of specialized indexes—covering narrow or less liquid segments of the market—has made it more challenging for many ETF managers to hit their targets for four reasons:

1. Fees and expenses. The higher the ETF’s fees and expenses, the higher its tracking error—since the benchmark normally includes no allowance for costs at all. And the specialized ETFs that have been launched recently have tended to have higher fees than those based on broader indexes.

2. Diversification requirements. Narrow indexes are often highly concentrated in a few holdings, which can make them very tough to replicate while still complying with regulatory requirements regarding diversification.

3. Sampling. If an ETF can’t replicate its index exactly, it must use sampling. And with sampling, unanticipated factors such as distortions in the pricing of derivatives or changes in the correlations of index components can generate tracking error. These are most likely during periods of high market volatility.

4. Cash management. ETF managers risk expanded tracking errors if they don’t manage their cash flows effectively. This is especially problematic when there are a lot of creations or redemptions.

Moreover, leveraged and inverse ETFs face particular challenges when it comes to tracking error, as we’ll see later in this section.

Since ETFs are exchange-traded, it can be argued that tracking errors are less important than market prices. But remember that market prices should reflect underlying NAVs. As tracking errors increase, they make NAVs less reliable and introduce greater unpredictability into the calculus of investors and arbitrageurs. And tracking errors don’t necessarily need to be negative: in 2009, a Vanguard Telecom Services ETF bested its target index by 17 percent!

Tracking errors: something investors and portfolio managers need to keep track of.

While passive management sounds very conservative, some ETFs have used it to take a very aggressive approach to investing. These are the inverse, or short, ETFs and the leveraged ETFs that work their magic by buying and selling derivatives. Inverse ETFs enable investors to profit from declines in the market—so that if the S&P 500 were to fall 10 percent one day, an inverse ETF on the S&P would be expected to gain 10 percent. Leveraged ETFs give investors a chance to multiply their gains—or their losses. For example, investors who owned shares in an ETF that provides exposure to the S&P 500 leveraged three times would expect a 30 percent profit when the S&P gains 10 percent. When the S&P loses 10 percent, that same ETF would be expected to decline 30 percent. Inverse and leveraged ETFs can be combined. An investor who was convinced that the S&P 500 was going to fall would want to buy a leveraged, inverse ETF on that index.

Note that the inverse ETFs target their indexes daily, which means that their returns can deviate from the index quite significantly over the long term. Let’s look at the hypothetical Windy Corner 2x Leveraged ETF that’s leveraged two to one to an index. Let’s say that the index rises by 20 percent on the first day, then falls 10 percent on the second, for a total two-day return of 8 percent. The ETF would move twice as much as the index on each day, so it would rise 40 percent on the first day and fall 20 percent on the second. That’s a two-day return of 12 percent, which is only 1.5 times the index return. (Table 12.4 summarizes these numbers; we’re ignoring expenses.)

TABLE 12.4 Windy Corner 2x Leveraged ETF

| Index value | ETF NAV | |

| Day 0 | $100 | $100 |

| Day 1 | $120 = $100 + 20%) | $140 = $100 + 40% |

| Day 2 | $108 = $120 – 10% | $112 = $112 – 20% |

| Two-day return | +8% = $8 gain / $100 | +12% = $12 gain / $100 |

These supercharged ETFs—and, specifically, their performance during the credit crisis—have drawn very negative attention in the press and a lot of scrutiny from the regulators. For example, one inverse ETF—leveraged two times to its index—fell 48 percent during a period when its underlying index fell 39 percent—a time when investors would expect strong positive returns from this investment. Some investors who experienced losses have taken their grievances to court.

Both the SEC and FINRA have taken steps to improve disclosure about how these funds work and imposed limits on investors borrowing to buy shares of such ETFs. In March 2010, the SEC announced that it will defer review of exemptive applications for new ETFs that plan to use derivatives extensively until it can develop rules to improve disclosure and regulation for these funds. In the meantime, some brokerage firms have restricted sales of these ETFs by their financial advisers.

Another set of index ETFs use enhanced index investment approaches that seek to improve on the performance of an index using a quantitative security selection techniques. The formulas for these enhancement strategies are disclosed so that portfolio composition is predictable. As a result, while these ETFs involve an element of active portfolio decision making, they do not raise the concerns that have attached to fully actively managed ETFs, as we’ll see in a moment.

Actively managed ETFs. Fund sponsors have long viewed actively managed ETFs as the Holy Grail, the portfolio approach that would put ETFs on an equal footing with traditional mutual funds. Still, active ETFs have been very slow to launch, largely because portfolio managers fear that they could be vulnerable to front running. As we’ve seen ETFs depend on arbitrage to keep their NAV and their share price in line; to make the arbitrage process work, ETFs must be completely transparent, publishing their holdings data at least once a day.

Active managers generally don’t like operating in that kind of spotlight; in fact, as we saw when we reviewed securities trading in Chapter 8, they go to considerable lengths to keep their activities out of the public eye. They don’t want other traders anticipating their actions and placing trades in front of them, a strategy known as front running. In the eyes of many active managers, the portfolio composition files published daily by ETFs—which may include information on trades that have been started but not yet completed—are nothing more than a license for this front running.

No surprise then that the first active ETFs were fixed income funds that focused on U.S. Treasury and money market securities. Their sponsors apparently felt that disclosing the portfolio compositions of these funds would not seriously impair their investment strategies given the depth of the markets for the portfolios’ fixed income securities.

The actively managed equity ETFs that have been subsequently introduced have triggered more of a debate in the fund industry on whether the risks of front running outweigh the other benefits of ETFs. Advocates of active ETFs argue that they provide a benefit because they allow mutual fund managers to sponsor funds specifically for active traders and market timers, accommodating such investors without potential harm to the long-term buy-and-hold investors in their regular mutual funds. Some ETF sponsors have recently proposed active ETFs that would disclose details on only a portion of their portfolio, providing only summary statistics on the balance. They believe that this compromise would prevent front running but still allow for efficient arbitrage. The SEC is still mulling over these proposals.

Despite the front-running concerns, active ETFs continue to gain adherents. By year-end 2009, there were 22 actively managed ETFs managing about $1 billion, a small, but growing, portion of the market, according to the Investment Company Institute.

What Does the Future Hold for Exchange-Traded Funds?

The fuss about actively managed exchange-traded funds is important because—if ETFs are to challenge traditional mutual funds—they must dramatically expand their investor base. To date, ETFs have appealed largely to wealthier individuals and institutional investors. On average, households owning ETFs have $120,000 in annual income and $350,000 in assets; that compares to $80,000 in income and $150,000 for the average mutual fund–owning household. More than 90 percent of the retail owners of ETFs have investments in stocks. ETFs are also popular with institutional investors, including mutual funds, who may use ETFs in lieu of derivatives to manage their exposure to the market.9

On the flip side, only 5 percent of the households that own funds have positions in ETFs. The new vehicles have failed to penetrate some of the core markets for traditional mutual funds. As we’ve seen, there are still very few actively managed ETFs—while active funds account for more than 80 percent of traditional fund assets. According to Cerulli Associates, ETFs make up only 5 percent of financial advisers’ product mix, even though these advisers are involved in the majority of mutual fund sales. And ETFs have little presence yet in the defined-contribution retirement plans that account for one-quarter of mutual fund assets. Like company stock, ETFs must be unitized to be held in a 401(k) or other defined contribution plan, which imposes additional costs. (See Chapter 11 for more on these plans.) Also, many of these plans would not be comfortable paying brokerage commissions to acquire ETF shares.

Still, the interest in ETFs is high, and their outlook is bright. Amazon.com offers more than 200 books and articles relating to ETFs. Its top-selling item, The ETF Book, has six chapters—over 70 pages—of advice on structuring investment portfolios using just ETFs.10 Many believe that with their perceived lower internal costs and more efficient operating structure, ETFs are well poised to grab market share from traditional funds. Others question whether ETFs will lose their advantages as they become more and more like traditional mutual funds, paying the same fees for active management or access to distribution through wrap accounts and other packaged products.

HEDGE FUNDS

The pros and cons of hedge funds have become a topic of discussion not just in the media, but at cocktail parties. In 1969, 20 years after the launch of the first hedge fund, the SEC estimated that there were 200 hedge funds with a total of $1.5 billion in assets under management. According to HedgeFund.net, by the end of 2009, the numbers had grown to almost 5,000 hedge funds with $2.2 trillion in assets, a compound growth rate in assets of close to 20 percent per year. What are these vehicles that have attracted so much interest?

The term hedge fund, while not defined in any law or court case, refers to pooled investment vehicles that share certain investment and regulatory characteristics. On the investment side, hedge funds seek to generate consistently positive returns in all kinds of markets, with low volatility and low correlation to the returns of other asset classes. To generate these returns, hedge funds employ diverse investment strategies—strategies that mutual funds generally find difficult to implement.

On the regulatory side, hedge funds and their advisers are exempt from many of the regulations governing mutual funds and their advisers. As a result of those exemptions, hedge funds can:

- Invest in a wide variety of assets, including large positions in illiquid assets that can be difficult to sell

- Require investors to remain in funds for months or years at a time

- Use large amounts of borrowed money—or leverage—to try to enhance investment returns

- Engage extensively in short sales

- Charge performance fees based on gains, in addition to management fees based on assets

CAREER TRACK: HEDGE FUND MANAGER

What’s involved in running a hedge fund? The big surprise in store for many start-up hedge fund managers is that the hedge fund business involves substantially more than investment acumen. Running a hedge fund involves all of the chores and headaches of running any small business—in addition to the day-to-day challenges of investing.

That means you’ll spend a lot of your time marketing—rounding up new investors and holding on to existing ones—and most of these investors will want to talk with you personally. It’s a critical function since new investment capital is the lifeblood of hedge funds, and no hedge fund has ever grown to significant scale based on investment returns alone. You’ll also routinely get involved in personnel decisions, fund operations, space planning, compliance issues, and technology implementation.

And you’ll make some investment decisions as well. You probably started your career as an investment professional at a bank or investment adviser where you developed an investment approach. Running your own hedge fund gives you a chance to express your investment views on a relatively open canvas with relatively few restrictions. And if you make the right decisions, there’s the promise of a large payoff. But for every hedge fund manager who’s a billionaire, there are more than a few would-be investing stars struggling to pay the rent and payroll, imploring investors not to redeem, and staying up at night reading annual reports and sell-side research.

Importantly, it is the right to do these things, not the fact of doing them, that qualifies a fund as a hedge fund. That is, a hedge fund is not a hedge fund because it actually uses leverage to invest in illiquid assets and engages short sales. Rather, it’s a hedge fund because it has the legal right to engage in these activities, or more precisely, because it’s exempt from laws that prohibit engaging in these activities. More than anything else, hedge funds are defined by what they are not—namely, regulated.

But as they say on Wall Street and in Greenwich, Connecticut, where many of the best-known hedge fund managers are based, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. And so it is with hedge funds: as a price for their regulatory exemptions, Congress and the SEC have imposed limits on who may invest in hedge funds and how hedge fund managers may market their products. Generally, only investors that own at least $5 million in investments—excluding their homes—may participate in hedge funds. And hedge fund managers may not market themselves or their funds through any of the retail channels typically used by mutual funds, such as television, newspapers, magazines, radio, or Internet. The “Career Track” box talks about the life of a hedge fund manager.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Hedge Funds

Hedge funds offer certain investment and risk-mitigation advantages. But those advantages can be offset by disadvantages relating to fees, illiquidity, lack of transparency, and other matters.

Institutions, high net worth individuals, and others invest in hedge funds for seven primary reasons:

1. Alpha, or above-market, returns. Investors in hedge funds believe that their managers can generate returns with positive alpha, meaning returns that are higher than the market return. Alpha reflects the value added by a hedge fund manager’s skill.

2. Absolute returns. Hedge funds are intended to provide absolute returns—positive returns in any market environment over any reasonable measurement period. By contrast, most mutual funds are intended to provide relative returns, that is, returns that are measured by reference to a benchmark. For example, if the market goes down, most mutual funds are supposed to go down less than the market, but most hedge funds are supposed to go up. Hence the saying in the hedge fund world: “You can’t eat relative returns.”

3. Lower volatility. Hedge funds are intended to provide lower volatility, or variations in returns, than mutual funds. Hedge funds try to do this by taking offsetting positions in similar investments with different prospects. For example, if a hedge fund purchased shares of Exxon Mobil stock, it can limit its losses by also selling Royal Dutch Shell stock short. “Selling Short Yourself” describes the strategy in more detail.

SELLING SHORT YOURSELF

What exactly is short selling? It’s a way of making a profit when the price of a stock declines—by selling stock that you don’t own. To do this, you borrow shares of stock from another investor—with the help of a broker-dealer who arranges this securities lending—and then sell the borrowed shares.11 To close the short position, you buy shares in the market, then give them to the broker-dealer to repay the loan. If the price at which you sell the stock is higher than the price at which you buy it back, you will make money on the short sale.

Why would anyone lend stock to help another investor who wants its price to decline? Because you can make a profit doing it. The shorts—as short sellers are fondly (or not-so-fondly) called—must pay interest on the stock loan. And, in most circumstances, the risk of lending is limited. That’s because short sellers must set aside other high quality securities as collateral to guarantee that they will eventually return the stock; if they fail to do so, the lender gets to keep the collateral. (Securities lending did generate losses during the credit crisis of 2008. We discuss these problems in Chapter 14.)

Short selling is controversial. The shorts have often been blamed for large declines in the market, such as in 1929 and 2008, and for attacking companies in the media to see their stock prices decline. On the other hand, some of these attacks were well founded. Short sellers have been credited with exposing fraud and other irregularities, as they did in the cases of Enron and Lehman Brothers.

4. Low correlation. The returns of hedge funds are designed to be relatively uncorrelated with the returns of traditional asset classes because their portfolios are structured so that they are affected by different market events than are the returns of stocks and bonds—or affected to a different degree by the same market events. Accordingly, hedge funds have the potential to diversify an investment portfolio and thus reduce its risk.

5. Unique strategies and assets. Unlike mutual funds, hedge funds are exempt from regulatory restrictions on investments and, therefore, can invest in any asset—at least in theory. In practice, hedge funds are limited to the strategy stated in their private placement memoranda, which is the hedge fund analogue of a mutual fund prospectus.

Given this freedom, hedge funds don’t just invest in traditional asset classes like publicly traded stocks or Treasury securities; they often invest in quite illiquid assets like real estate, shares of private companies, and securities of companies in bankruptcy. (Remember that the liquidity of an asset refers to how difficult or easy it is to sell the asset.) These assets can offer some of the most interesting investment opportunities. Because the market for illiquid assets is frequently inefficient, they can often be purchased at a discount to their true value. Moreover, hedge fund managers can take actions that increase the value of illiquid assets, such as hiring a new management company to oversee a real estate investment. (“Looking at the Alternatives” explains the terminology used for these investments.)

LOOKING AT THE ALTERNATIVES

Assets other than publicly traded stocks and bonds are often referred to as alternative investments. There’s no official definition of this term, but it’s loosely used to refer to investments in commodities, real estate, derivatives, and private equity, which are investments in non-public companies, and venture capital, which are investments in firms that are just starting up.

The term is loosely applied to funds or managers that invest in these assets as well. So, hedge funds and hedge fund managers are often called alternative investments and alternative investment managers, respectively.

6. Star management talent. The high compensation at hedge funds and relatively unfettered investment discretion allowed hedge fund managers is thought to attract high-caliber investment management talent.

7. Manager co-investment. Hedge fund managers often invest substantial personal assets in their own funds. Such hedge fund manager investments are believed to align the incentives of managers and fund investors.

Critics express five main concerns with the hedge fund business model:

1. Advantages reconsidered. Perhaps most importantly, detractors question whether hedge funds have actually delivered on the promises they have made to investors, a critique that has only gained visibility after the credit crisis. During that turmoil, many hedge funds failed to deliver alpha, with some hedge funds declining further and faster than the market. Similarly, many hedge funds actually fell in value and thus did not provide positive absolute return. As a group, hedge funds were quite volatile and had negative, correlated returns.

To compound the case against hedge funds, mutual funds are starting to incorporate some of the investment advantages previously only available in hedge funds, such as absolute return strategies and volatility management techniques. And it’s not clear that hedge fund managers—many of whom started their careers in mutual fund management—have any greater skill than their counterparts running more traditional funds.

2. High fees. Hedge funds are often criticized for their high fee structure. They generally pay their managers two types of fees: a management fee and a performance allocation, also known as the carry, or carried interest. The management fee is calculated as a percentage of assets under management, while the performance allocation is calculated as a percentage of realized capital gains. Traditionally, the management fee has been 2 percent, and the carried interest has been 20 percent, a fee structure referred to in the industry as “2 and 20,” although the management fees of sought-after hedge funds have often been higher. Contrast that to an average management fee of less than 1 percent for a stock mutual fund—which may not charge a performance fee unless it prevents a penalty for losses as well as a reward for gains. (Chapter 15 has more on mutual fund performance fees.)

The management fee is taxed as ordinary income, and historically, carried interest was taxed as long term capital gains. However, Congress is seriously considering legislation to increase the tax rate applicable to carried interest. Although hedge fund managers will not earn less than the base fee—even when performance is poor—the performance allocation is generally subject to a high water mark. This means that a hedge fund manager will not earn a performance fee unless the value of the hedge fund at the end of a given year is higher than its value at the end of any previous year. “Getting Out from Under Water” has an example of a hedge fund fee calculation.

GETTING OUT FROM UNDER HIGH WATER

Let’s look at how a high water mark provision works in practice. Let’s assume that the Avon Hill Fund has a 2 and 20 fee structure and $1.0 billion in assets under management at the start of Year 1. As shown in Table 12.3, if returns were positive during that first year and the value of the fund rose to $1.1 billion, the fund would pay its manager management fees of $22 million—equal to 2 percent of the $1.1 billion fund value—and a performance allocation of $20 million—equal to 20 percent of the gain in fund value from $1.0 billion to $1.1 billion. (We’re assuming in this example that all gains were realized through the sale of the fund’s portfolio holdings.) The $1.1 billion account value now becomes the high water mark.

Let’s now assume that returns were negative in Year 2, causing the fund value to drop to $0.9 billion. The fund would still pay a 2 percent management fee of $18 million, but it would not pay a performance allocation since the fund value fell below the high water mark of $1.1 billion. Even if the fund then regained some ground in Year 3, it would still be under its high water mark and therefore would again not pay a performance allocation. It would take another gain in Year 4 before the fund would exceed its high water mark. If the fund value were $1.2 billion at the end of that year, the fund would pay a performance allocation of $20 million, which is 20 percent of the difference between the new fund value and the high water mark of $1.1 billion. The value of $1.2 billion now becomes the new high water mark. Table 12.5 has a summary.

TABLE 12.5 Avon Hill Hedge Fund Fee Calculation

3. Lack of liquidity. Hedge fund investors are not able to redeem their investments on a daily basis as are mutual fund investors. Most hedge funds offer investors the right to redeem only quarterly, semiannually, or even annually, and some newer hedge funds have longer lock-ups, often for a period of two years. Hedge funds that invest in illiquid investments often have special provisions such as gates, side pockets, or redemption suspension rights that keep investors in the fund for long periods; that’s to avoid having to sell those assets at fire sale prices to raise cash to pay redeeming investors. (See “Hedging Vocabulary” at the end of this section for a glossary of hedge fund terminology.)

4. Transparency. Investors frequently complain that hedge fund managers don’t give them enough data—neither often enough nor in enough detail—to enable them to monitor their investments effectively. In other words, hedge funds are not transparent, allowing investors a clear view of their inner workings. As we saw in Chapter 3, disclosure in the mutual fund world is determined by government regulation—which requires that funds regularly publish lists of holdings and reviews about performance. For hedge funds, in contrast, the release of information is governed by their contract with investors.

Those contracts may favor larger investors. Unlike the mutual fund world, where large investors may get slightly reduced sales loads or qualify for a lower-cost class of shares but otherwise get the same deal as smaller investors, in the hedge fund world, different investors in the same fund may have dramatically different rights. Large investors may negotiate for daily reports on fund positions and may receive special redemption rights and may be charged lower fees. Hedge fund managers effectuate these special deals with large investors through two methods: side letters and managed accounts. (See “Hedging Vocabulary” for definitions.)

5. Overstatement of performance results. Academic studies have found that average hedge fund returns as reported in the media are overstated—by more than 2 percent per year—creating an unduly rosy picture of their investment prowess.12 That’s because the central databases suffer from considerable backfill bias and survivorship bias. Backfill bias results when managers report only favorable past returns. For example, a hedge fund may open up in Year 0 but not start reporting results to the databases until the end of Year 2—and then only if the numbers for the two years of its existence look good. As backfill bias relates to the startup of a hedge fund, survivorship bias occurs when it shuts down—most often because its performance has been poor. Once the fund closes, its entire track record is deleted from the database, adding another upward bias to the average numbers. Since starting up and shutting down a hedge fund is relatively easy to do, the average life span of a hedge fund is quite short—only three to four years—so there is ample opportunity for both types of bias to come into play.

In contrast, opening and closing a mutual fund is much more difficult and costly, which means that backfill and survivorship bias play much less of a role—though they don’t disappear altogether. Fund management companies sometimes close poorly performing funds—usually by merging them into another fund—to eliminate their track record. Much less frequently, a sponsor may sell a mutual fund to a relatively small number of investors in a public offering and later start selling it to the world at large only if it amasses a positive performance record. But the overall effect of the two types of bias is much lower than in the hedge fund world.13

Hedge Fund Strategies

Given the flexibility of the hedge fund format, hedge funds can pursue a wide variety of investment strategies. Some of the more common hedge fund investment strategies include:

- Equity long-short. Equity long-short was the strategy used by A.W. Jones & Co., the first hedge fund, and remains the most popular hedge fund strategy today; approximately 30 percent of all hedge fund assets globally are allocated to this strategy or a variation of it. Long-short involves buying stocks long and selling stocks short at the same time. Hedge funds usually buy stocks they consider undervalued and short stocks they consider overvalued. (Chapter 5 gives a brief description of the long-short strategy.)

- Relative value or arbitrage. Relative value is a long-short strategy involving specific types of securities or assets other than stocks. One of the oldest hedge fund strategies is merger arbitrage; hedge funds using this strategy buy shares of a company that is in the process of being acquired and short the shares of the acquirer. Relative value managers will look at past relationships among different securities issued by the same company and look to profit when they vary from historical norms. One variant on this strategy is convertible arbitrage, which involves buying a convertible security and selling short the underlying stock. Intercredit strategies look at relative value relationships between different types of fixed income securities, such as corporate bonds versus government bonds.

- Distressed. A distressed strategy involves purchasing the securities or other assets of a company in or near bankruptcy.

- Shareholder activism. Activist hedge funds seek major changes in the way a company is managed. (Chapter 9 discusses shareholder activism.)

- Global macro. This strategy involves taking a view on macroeconomic events such as changes in interest rates, the relative value of currencies, or the global supply and demand for natural resources. Probably the most famous global macro trade was George Soros’s short sale of the British pound in 1992, which earned Soros the sobriquet “The man who broke the Bank of England.”

- Managed futures. Also known as commodity trading advisers, managed futures hedge funds invest in futures contracts on various types of commodities—including energy, metals, and grains—and on the financial markets.

- Multistrategy. As the name implies, these hedge funds invest across all the foregoing strategies and others besides. Multistrategy funds have fallen out of favor for two related reasons. First, investors do not want to wind up overweighted in a particular strategy, as they can if a multistrategy fund drifts toward the strategy of another hedge fund in the investor’s portfolio. Second, investors want managers to stick to core investment competencies and to strategies with which they have proven track records.

- Leverage. Leverage is a critical underlying strategy of many hedge funds, used together with any of the previously listed strategies. As we discussed when we reviewed leveraged exchange-traded funds, leverage allows funds to increase the impact of their investment decisions. Funds can increase leverage in one of two ways: they can either use derivatives that have a potential for a large payoff on a small investment, or they can borrow money, hoping to earn the spread on the return on their investments and the cost of the loan. Leverage allows hedge funds to earn spectacular returns on the upside when they make good investment decisions—and to fail equally spectacularly when they don’t.

In theory, the hedge fund strategies we’ve just described are not limited to hedge funds. An individual investor is free to pursue a global macro strategy, for example, and an equity long-short approach would fit well with the investment goals of many mutual funds. But for practical and regulatory reasons, these strategies have been much more heavily used by hedge funds than other types of investors. Individual investors may not be able to own many illiquid assets; purchases of these investments are often restricted to institutional buyers. And the 1940 Act places limits on short selling and leverage by mutual funds. Remember from Chapter 2 that a mutual fund’s borrowings can’t exceed one-third of the value of its assets; short sales, which involve borrowing stock, are included in this limit. In contrast, borrowings at hedge funds often equal 80 percent of assets.

Despite the difficulties, a few mutual funds have begun to use these strategies to the maximum extent permissible. They are said to use hedge strategies or alternative strategies to achieve the same ends as hedge funds themselves—higher returns and lower volatility.

Hedge Fund Investors

There are three main types of investors in hedge funds:

1. Institutional investors. Institutional investors, particularly traditional pension funds, account for a significant and growing proportion of assets under management of hedge funds globally.

2. Individual investors. Individuals have been another noteworthy category of hedge fund investors; they are particularly important for start-up managers who are often staked by friends and family. As we’ll discuss shortly, investors in hedge funds are usually quite well off; most funds require that they have at least $5 million in investments.

3. Fund of funds. But the largest investors in hedge funds are other hedge funds; these are the hedge “fund of funds” that allocate assets to multiple hedge fund managers. Institutional investors (such as pension funds, endowments, and foundations) invest in funds of funds for their presumably superior expertise in selecting underlying hedge fund managers. Fund of funds managers stress their careful due diligence, or research, into potential hedge fund investments and their ongoing monitoring of positions.

The fund of funds model has come under serious criticism, however, for providing returns that only equal or even underperform their benchmark indexes, while adding another layer of fees—often a 1 percent base fee plus a 10 percent performance fee—on top of the fees charged by underlying managers.14 Also, a number of hedge fund of funds were heavily invested in the Madoff Ponzi scheme, calling into question the value of their due diligence process.

Hedge Fund Regulation

As we talked about in the introduction to this section, hedge funds in the United States are exempt from many of the laws and regulations that govern mutual funds. Let’s look closely at how this works in practice.

At the fund level, hedge funds are structured so that they do not fall within the definition of investment company under the 1940 Act, and therefore do not have to register with the SEC. No registration equals no limits on leverage, short sales, or illiquid investments, no rules on the types of fees that can be charged, no required disclosure, and no need for an independent board of directors.

Hedge funds avoid registration in two ways. First, many incorporate in low-tax countries outside the United States, like the Cayman Islands; these offshore hedge funds fall outside the jurisdiction of the 1940 Act. Hedge funds also avoid making a public offering to U.S. investors, because investments that are publicly offered in the United States, such as mutual funds, must be registered with the SEC—even if offered by an offshore fund.

Instead, hedge funds make sure that their marketing activities fall under the definition of private offering. They do not market themselves or their funds through conventional retail channels such as television, newspapers, magazines, radio, or Internet. They also limit the type and number of investors in the fund. They may accept a maximum of only 100 accredited investors who are individuals who have a net worth of at least $1 million after excluding the value of their primary resident or who had an income of at least $200,000 in each of the past two years. (The 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation requires that this amount be adjusted for inflation at least every five years.) Alternatively, hedge funds can accept up to 499 investors if they require all those investors to have at least $5 million in investments. Most hedge funds rely on this latter provision and often ensure compliance with it by requiring a $5 million minimum investment.15

In sum, hedge funds are exempt from many of the more onerous laws and regulations governing registered investment funds. As a price for those exemptions, hedge funds are limited in the people and entities from whom they may accept investments, and hedge fund managers are limited in their ability to market their wares. However, the price may not be so high in practice, because the structure and strategies of hedge funds do not lend themselves to retail investing in the first place. In particular, the illiquidity of many hedge funds does not fit the cash flow needs of many retail investors. For example, most people wouldn’t want their child’s college money to get stuck behind a hedge fund gate.

There are three chief arguments in favor of these exemptions from regulation, namely:

1. Knowledgeable investors. Defenders of light regulation for hedge funds note that only investors with considerable assets can own hedge funds, and these investors can fend for themselves without regulatory protection. Proponents of more regulation counter that size and financial wherewithal do not necessarily translate into sophistication, as recently highlighted in the SEC’s lawsuit against Goldman Sachs for its structuring and marketing of credit derivatives to European banks.

2. Little systemic risk. Hedge fund advocates suggest that, because of their comparatively low level of assets under management and the diverse strategies used, hedge funds do not pose a systemic risk to the financial system. In other words, problems at a single hedge fund or even at many hedge funds, would not do significant damage to the U.S. financial system. But critics point out that while hedge funds are small relative to mutual funds or banks, hedge funds’ ability to use leverage and derivatives can dramatically enhance their collective exposure. Small size didn’t prevent a hedge fund called Long-Term Capital Management from causing widespread panic in the financial system in 1998.16

3. Self-regulation. Self-regulation by knowledgeable hedge fund investors, creditors, and counterparties serves as a workable proxy for government-imposed regulation. (Creditors lend money to hedge funds, while counterparties engage in other transactions with hedge funds—such as securities lending and derivatives trades—which involve credit risk.) But it’s not clear that these parties can be relied upon to regulate others when they themselves pose significant risk to the financial system. Most notably, before its demise, Lehman Brothers was a significant hedge fund creditor and counterparty, but employed significantly more leverage than any of its hedge fund counterparties or borrowers.

In the wake of the credit crisis, the advocates of tighter regulation have gathered strength, and new legislation in both the United States and Europe have led to increased supervision of hedge fund managers. In the European Union, where hedge funds and hedge fund managers are already subject to regulatory oversight in several countries, the Alternative Investment Fund Managers directive will require that all EU countries impose a stricter regulatory regime on hedge fund managers. Furthermore, hedge fund managers from countries outside the European Union will not be allowed to raise funds in the EU unless those non-EU countries meet certain standards in regulating hedge fund managers.

In the United States, within one year of the mid-2010 enactment of the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation, U.S. hedge managers will be required to register with the SEC as investment advisers, as long as they have at least $150 million in assets under management; previously, they were exempt from this registration requirement.17 As a result, hedge fund managers must appoint a chief compliance officer, must have and enforce a code of ethics, must maintain and file specified reports, and must distribute a brochure to the clients every year with information about their firm. Moreover, hedge fund managers registered as investment advisers will be subject to periodic inspections by SEC staff. However, these managers will still be allowed to charge wealthy investors performance fees based on realized gains (not offset by losses) and to adopt any investment strategy with any amount of leverage they please. Moreover, despite the new oversight of hedge fund managers, hedge funds themselves will remain largely unregulated.

HEDGING VOCABULARY

Like any industry, the hedge fund industry has many unique terms and concepts. Here are the definitions of the terms we used in this section:

Gate. A hedge fund provision that prevents a large percentage of investors from redeeming at once. Specifically, if more than a certain percentage of investors—usually 10 to 30 percent—want to redeem at the same time, the manager only has to satisfy redemptions representing that 10 to 30 percent of assets and can carry the remainder forward to the next scheduled redemption date. Managers include gates to prevent fire sales of assets and to ensure that remaining investors don’t end up with a very illiquid portfolio after a manager sells the more liquid assets to raise cash to pay redemptions.

Lock-up. The period an investor can’t redeem from a hedge fund. For example, in a two-year lock-up, an investor must remain in the fund for two years from the date of investment. Following that lock-up, the investor may have the right to redeem annually, semiannually, or monthly.

Managed account. A mini–hedge fund for one investor. This structure provides complete transparency on holdings and activity, but only for that one investor.

Redemption suspension. The right of a hedge fund manager, often included in hedge fund governing documents, to refuse to satisfy redemption requests from investors in specified circumstances. These circumstances may include a determination by the manager that selling assets to raise the cash required to pay redemptions would adversely affect the value of the fund.

Side letter. A special agreement with a large investor in a hedge fund. For example, a side letter may grant a certain investor preferential redemption rights or additional access to portfolio data.

Side pocket. A separate account within a hedge fund that is set up by the manager to hold illiquid assets. After a hedge fund manager transfers an asset from a hedge fund to a side pocket, investors redeeming from that hedge fund do not get the value of their pro rata interest in the side-pocketed asset. Rather, they only get their interest when the asset is sold, which can be years after they redeem from the hedge fund.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Exchanged-traded funds, or ETFs, and hedge funds are fast-growing competitors to traditional mutual funds.

ETFs are similar to mutual funds, but have shares that trade on a stock exchange. They allow investors to buy shares throughout the day with no minimum investment, though buyers must pay a brokerage commission to execute the transaction. Most ETFs are organized as mutual funds or unit investment trusts. However, other ETFs take advantage of structures that enable them to invest in commodities, real estate, or currency—investments that are difficult for traditional mutual funds to invest in extensively.

While traditional mutual funds issue shares directly to investors, ETFs create or redeem shares through an authorized participant that has signed an agreement with the ETF. To create shares, the authorized participant buys a basket of securities that matches the portfolio held by the ETF, and then exchanges that basket for ETF shares. This unique creation and redemption process helps ETFs minimize capital gains. Arbitrageurs—who are usually Authorized Participants—use the creation and redemption process to keep the ETF’s share price in line with its NAV. While this system has generally worked well, significant differences between share price and NAV have at times occurred.

Most ETFs are index funds that use a passive investment strategy. However, some index ETFs use leverage and have a very aggressive approach as a result; these ETFs have been quite controversial. A few actively managed ETFs have been launched recently, despite concerns that they are vulnerable to front running because they have to disclose their portfolio holdings at least daily.

Hedge funds are unregulated pooled investment vehicles. Investors choose to put their money in hedge funds because they believe they will provide high returns in any market environment and that those returns will have a low correlation with the returns of traditional investments. Hedge funds have the freedom to invest in a wide range of assets. Hedge fund managers frequently place a large percentage of their own assets in the fund alongside investors.

Critics of hedge funds point out that these vehicles have often failed to deliver their expected returns and that their average returns are overstated. Hedge funds also charge high fees. They frequently place restrictions on investor redemptions, and they provide little information about their activities, at least to smaller investors.

Hedge funds use a variety of investment strategies. Many of these strategies involve short selling—to profit from a decline in the value of an investment—and leverage, which increases the impact of decisions. The largest investors in hedge funds are funds of funds, which allocate assets to multiple hedge fund managers.

To avoid regulation in the United States, hedge funds must limit the number of investors, and those investors must meet certain minimum standards for net worth. Regulation of hedge fund managers is increasing in both Europe and the United States. Recent U.S. legislation requires that the managers of hedge funds register with the SEC as investment advisers, although the funds themselves do not have to be registered.