Chapter 3

Researching Funds: The User Guides

Now that we’ve studied the advantages and disadvantages of mutual funds and taken a look at how they work, you’re ready to begin researching a potential fund investment. Much of the information you’ll need will come directly from the fund itself. In fact, funds are required by law to disclose essential information to investors in the fund—providing what are, in effect, user guides for potential buyers. This chapter examines the documents that funds prepare to do just that. Looking ahead, in the next chapter, we’ll take a look at independent sources of information that you can consult to learn even more about possible fund choices.

This chapter reviews:

- The principle of disclosure and how it applies to mutual funds

- The content of the summary prospectus, the key document that funds provide to prospective buyers

- The other documents that must be prepared by funds: the statutory prospectus, the statement of additional information, and the shareholder reports

- How investors can use the information in these documents to help select funds for their portfolios

MUTUAL FUNDS AND DISCLOSURE

The underlying principle of U.S. securities regulation is disclosure, the concept that the seller of a security has an obligation to tell potential buyers essential facts about the investment. Under U.S. law, anyone who wants to sell a security to the public must:

- Register the offering of the security with the SEC

- Provide buyers with a document called a prospectus, which discloses material information about the investment, meaning information that’s likely to be important to the investor

- Report periodically to buyers about their investment after the security has been issued

See “Landmark Legislation” for information on the source of these rules.

LANDMARK LEGISLATION

The first two pieces of securities legislation passed as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal remain the cornerstones of U.S. securities regulation today:

1. Securities Act of 1933. Because this 1933 law mandated disclosure of material information through a prospectus, it is sometimes referred to as the truth in securities act. The Securities Act also established the requirement for registration of securities.

2. Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The Exchange Act set down annual and quarterly reporting requirements for issuers of securities. It is also the legislation that created the SEC.

Disclosure creates transparency, an environment in which potential investments are not black boxes but glass houses, whose inner operations are easily seen and analyzed. Buyers benefit from transparency because they have ready access to the data they need to make an informed decision about a potential investment. And because all sellers must disclose similar information, investors are able to compare offerings fairly easily.

Note that the responsibility for making disclosure falls fully on the shoulders of the seller. Even though the seller must file a draft, or preliminary, prospectus with the SEC, the agency never actually approves any prospectus—though it may, on some occasions, prevent the issuance of a prospectus if it fails to meet the relevant requirements. But the SEC is not opining on the accuracy or completeness of the content. In fact, every final prospectus includes the disclaimer that:

Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission nor any state securities agency has approved or disapproved of these securities or determined whether this prospectus is truthful or complete. Any representation to the contrary is a crime.

The burden of disclosure does carry an offsetting benefit: sellers who make full disclosure enjoy considerable protection against lawsuits. Buyers can’t sue the issuer of a security simply because the security has gone down in price. Instead, they must prove that a seller omitted or misrepresented an important fact from the relevant disclosures—called a material misstatement—either intentionally or because they failed to exercise sufficient care in preparing their documents. Buyers must also demonstrate that they relied on misinformation in the offering documents when making their purchase decision and that they suffered a financial loss as a result.

As a result of this protection, sellers are willing to offer a wide range of securities. If they were afraid of litigation every time the price of a security went down, they’d limit offerings to only the safest of bonds, investments that would be unlikely to provide much by way of potential return. Instead, under a disclosure regime, sellers are more willing to offer securities with even very high levels of risk.

And that, in turn, is good for buyers, who have access to a greater number and variety of investment opportunities—and who are given the information they need to judge for themselves whether the potential reward justifies the risk involved. For society as a whole, disclosure leads to more active securities markets.

Because they are considered issuers of securities, mutual funds are subject to all of the requirements of the disclosure rules. They must register their shares with the SEC, prepare a prospectus for potential buyers, and provide periodic reports to investors.

Disclosure poses particular challenges for mutual funds, in two ways. First, because most funds sell shares to the public every business day, they must have an accurate prospectus available at all times. Contrast that with the typical operating corporation, which needs to raise money from the public only every few years. That company will prepare a prospectus just before issuing stocks or bonds. After the offering is completed, they needn’t worry about the prospectus until they are ready to raise capital again.

Prospectuses for mutual funds, on the other hand, are continually in use. Funds review them regularly, doing a complete update roughly once a year, but also amending them during the year if there have been any significant changes. These intra-year amendments are informally called stickers, because state law used to require that they be literally stuck to the paper version of the prospectus. In an electronic version, you’ll usually see them first as you scroll through the document. (See “Prospecting for Fund Documents” for a guide to online access.)

PROSPECTING FOR FUND DOCUMENTS

Finding fund documents is easy online. There are two places to look them up on the Web:

Option 1: Visit the management company’s web site. Since a sponsor generally offers many funds—sometimes many, many funds—you’ll need to find the page for the particular fund you’re interested in. In some cases you may need to look for a navigation element labeled documents, or literature. When you do find what you’re looking for, usually only the current document set will be available.

Option 2: Ask EDGAR. That’s the Electronic Data Gathering and Retrieval system maintained by the SEC. It’s available online at www.sec.gov/edgar.shtml. Here you can access absolutely all the filings the fund has made with the SEC over roughly the past 15 years—not just the key disclosure documents we look at in this chapter.

The second disclosure challenge for mutual funds is the diversity of the investors they serve, in terms of the type of information they or their representatives would like to receive. Some shareholders—those buying through their 401(k) plan, for example—may be comfortable with just a broad overview of the fund. These individuals may want to know only about the fund’s general investment approach, its risks, and its costs. Others—possibly corporate gatekeepers who decide whether to include the fund as an investment option in that same 401(k) plan—may be interested in all the details, such as the specific investment techniques that may be used or the qualifications of the members of the board of directors.

As a result, over the years, the SEC has developed a tiered approach to fund disclosure. Funds prepare a series of documents describing the fund and its policies with varying levels of detail; investors then choose the document that best suits their needs. The prospectus now comes in three different forms. From shortest to longest, they are the:

1. Summary prospectus. As the name implies, this is a brief document, typically only three or four pages long, designed for the investor who wants just the highlights. It must be written in plain English. (See the “Plain-Speaking Prospectuses” for the SEC’s definition.)

PLAIN-SPEAKING PROSPECTUSES

The SEC encourages companies to use plain English in their disclosure documents and even requires its use in the summary prospectus. It offers some specific guidelines on how to make disclosure documents readable. The SEC suggests that writers:

- Use active (not passive) voice

- Write in short sentences

- Use definite, concrete, everyday words

- Use tables and graphics, rather than text, to explain complex material whenever possible

- Avoid legal jargon and highly technical business terms

- Avoid multiple negatives

More generally, the SEC asks prospectus writers to know their audience, to highlight the information that is most important and to design the layout of the prospectus in a way that’s easy and inviting to read. The SEC provides a 77-page manual titled The Plain English Handbook: How to Create Clear SEC Disclosure Documents, with guidance on writing in plain English. It’s available at www.sec.gov/pdf/handbook.pdf.

2. Prospectus. The full, or statutory, prospectus contains all the material information that the SEC believes is needed for an investor to make an informed purchase decision. The content of the summary prospectus forms the first section of the full prospectus.

3. Statement of additional information. Again, the name says it all. The SAI provides potential buyers who are interested in detail with quite a lot of it. It is technically Part II of the prospectus.

We focus on the summary prospectus, and then take a quick look at the other two forms of the prospectus and the shareholder reports that funds prepare at least twice a year.

THE SUMMARY PROSPECTUS

The summary prospectus is the key user guide for the mutual fund investor. It provides an overview of the fund’s investment objective, strategies, and risks, summarizes its past performance, and provides administrative information that is particularly relevant to shareholders.

The summary prospectus is fairly new; funds were first permitted to use it only in March 2009. Industry observers expect that it will eventually become the document most funds send to investors making a purchase of shares. (There is an alternate way of providing the necessary information, which we explain when we discuss the full prospectus.)

To ensure that the summary prospectus is a disclosure document and not a marketing document, its specific content is mandated by the SEC. To help investors make comparisons among funds, every summary prospectus must contain the following items in this exact order:

- Heading or cover

- Investment objectives and goals

- Fee table

- Investments, risks, and performance

- Management

- Purchase and sale of fund shares

- Tax information

- Financial intermediary compensation

We review the most important components of each section in turn. We’ve posted a sample summary prospectus on this book’s web site.

Section 1: Heading or cover. The summary prospectus opens by laying out the fund’s vital statistics. The first things the reader sees, either on the first page or a separate cover page, are:

- The fund’s name.

- The date of the summary prospectus.

- The classes of shares.

- The exchange ticker for each class (see “Keeping Your Funds Straight” for a definition).

- Information on how to get a copy of the full prospectus. Funds must offer to send the prospectus to you by either e-mail or snail mail, and they also must provide a web address for an online version.

We just mention share classes here. We cover them in depth in Chapter 10.

KEEPING YOUR FUNDS STRAIGHT

With more than 7,600 mutual funds available, it would be easy to mix up one with another. To prevent confusion, each mutual fund offered to the public (and each class of shares for that fund) has a unique identifier called an exchange ticker—similar to a Social Security number for individuals or an ISBN number for books. This ticker consists of five letters, often ending with X. For example, the exchange ticker for the BlackRock Equity Dividend Fund, Class A, is MDDVX.

You can use a fund’s ticker to look up information quickly on stock information services. Enter MDDVX in the “get quotes” box at the top of the Yahoo! Finance page, and you’ll be given basic statistics about the fund, including NAV.

Disclosure about key features of a fund actually begins with its name. The SEC has strict standards when it comes to names applied to mutual funds: in short, fund names cannot be deceptive or misleading. As is its custom, the SEC has laid down a number of specific rules and guidelines in this regard, which are outlined in Table 3.1. These rules cover only fund names that indicate the type of investments the fund plans to hold. Names that describe an investment strategy (such as growth or value) or generic names (like Voyager and Destiny) have not been defined by the SEC, though names may not under any circumstances paint a false picture for investors. For instance, Rock Solid or Super Safe would never pass muster as fund names.

TABLE 3.1 Limitations on Mutual Fund Names

| If the fund’s name… | Then the fund must… |

| implies that it will focus in a particular industry or type of securities… | keep at least 80 percent of its assets invested in that industry or type of investment. A biotechnology fund, for example, must put at least 80 percent of its assets in the biotech industry. |

| says it focuses in a particular country… | invest at least 80 percent of its assets in securities economically tied to that country. |

| contains the word foreign… | hold at least 80 percent of its investments in securities economically tied to countries outside the United States. |

| contains the words tax-exempt, tax-free, or municipal… | have at least 80 percent of its holdings in tax-exempt securities. Alternatively, at least 80 percent of the fund’s income must be exempt from taxes.1 |

| describes the fund’s maturity (as short-term, long-term, and so forth)… | maintain a portfolio of fixed income securities with an average portfolio maturity consistent with that name. For example, short-term funds should have an average weighted maturity of less than three years. |

| represents it as balanced… | hold a mix of equities and fixed income assets. Specifically, it must have at least 25 percent of its assets in bonds and at least 25 percent in stocks. |

Section 2: Investment objective. The body of the summary prospectus begins with a simple declaration of the fund’s investment objective, which is the type of return it is seeking to generate. Table 3.2 provides some examples. And if the name hasn’t already done the job, a fund may clarify which category it falls into (money market, tax-exempt, equity, and so on). We review the types of mutual funds in more detail in Chapter 4.

TABLE 3.2 Sample Investment Objectives

| Type of Fund | Typical Investment Objective |

| Money market | Maintain $1 value of its share while providing income |

| Investment grade bond | Current income |

| Tax-exempt or municipal bond | Current income exempt from federal income taxes |

| Equity income fund | Long-term capital appreciation and income |

| Aggressive growth equity fund | Long-term capital appreciation |

Section 3: Fee tables. The SEC wants investors to be well aware of the costs of owning a fund, so information on fees comes next, even before a discussion of risk and return. This section includes tables enumerating the annual operating expenses—in both percentage and dollar terms—and the sales loads, if the fund imposes them. (Remember that front-end sales loads or sales charges are fees paid when shareholders purchase shares.) Funds must also explain:

- If investors can reduce sales charges by increasing the size of their investment in the fund, a price reduction called a breakpoint discount.

- How portfolio turnover—meaning buying and selling securities within the fund—will affect costs. Turnover can increase costs in two ways. First, executing some trades involves the payment of transaction costs—an expense to the fund. Second, selling securities might generate capital gains, which could increase the shareholder’s tax bill for the year.

Taking our lead from the summary prospectus, we’re providing only the briefest of overviews here of fund expenses. We discuss the subject in detail throughout the book and provide a compilation of all fund expenses in Chapter 15.

Section 4: Investments, risks, and performance. This is the heart of the summary prospectus: It describes the fund’s investment approach, the risk of that approach, and the fund’s past success with that approach.

This section opens with a description of the types of securities the fund will buy and its method of choosing them. One fund may invest in U.S. equities that its managers believe to be undervalued, while another may buy stocks of companies based or doing business in the developing world that appear to have the potential for high growth. If a fund concentrates its investments in a particular industry or group of industries, it will be noted here.

THE DIFFICULTY OF DEFINING RISK

How best express the risk associated with a mutual fund?

Good question. Academics have long defined investment risk mathematically, by measuring the variability in an investment’s past returns. A U.S. Treasury bill has a narrow range of potential returns, while a biotech stock has wide range of potential returns.

Investors themselves define risk much less crisply, however. A 1996 survey by the Investment Company Institute explored investors’ thoughts about the risks of mutual fund investing.2 Asked to define risk, respondents said that it was the chance of:

Losing some of the original investment (57 percent)

Investment not keeping up with inflation (47 percent)

Value of the investment fluctuating up and down (46 percent)

Not having enough money at the end of the investing period to meet one’s goals (40 percent)

Income distribution from the investment is declining (38 percent)

Investment not performing as well as a bank CD (30 percent)

Investments not performing as well as an index (27 percent)

Losing money within the first year (23 percent)

Only 16 percent of respondents chose only one definition, while 55 percent chose three or more.

The multiple descriptions of risk in a prospectus—in both text and graphics—are designed to help investors determine whether the fund’s profile matches their own conception of risk.

The summary prospectus then goes on to describe circumstances that are reasonably likely to have a negative impact on the fund’s yield or return. The specific concerns vary widely depending on the type of fund. The prospectus for a blue chip stock fund might describe only two main risks: that the stock market overall may decline and that the stocks chosen for the portfolio may not do well. An emerging market equity fund may be concerned about foreign currency fluctuations or political risk in the countries it invests in, while a high yield bond fund might list many risk factors including a downturn in stocks, a rise in interest rates, defaults by issuers, and potential difficulties in selling the bonds the fund holds. The narrative also provides information on the fund’s best and worst quarterly returns. (“The Difficulty of Defining Risk” explains why the prospectus includes several different depictions of a fund’s risk.)

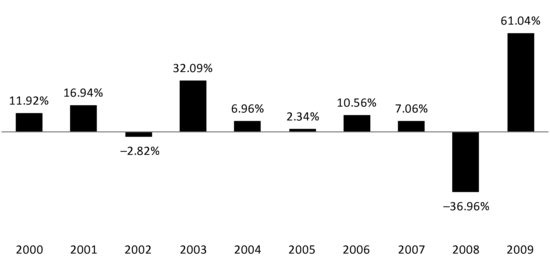

Funds must also include a bar chart showing the fund’s return in each of the past 10 years. (The period can be shorter if the fund hasn’t been in operation that long.) The ups and downs of the graph provide investors with a snapshot of how much fund shares can fluctuate in value which, in turn, gives investors some sense for the variability of that fund’s returns. Figure 3.1 gives a hypothetical example.

FIGURE 3.1 A Sample Risk/Return Bar Chart

To make it absolutely and positively clear that there is risk involved in mutual fund investing, the SEC also requires that all funds, except money market funds, state simply and explicitly that the value of fund shares may decline. Many fund documents say flatly:

You can lose money by investing in the fund.

After describing risk, this section of the summary prospectus concludes with a review of the fund’s past returns. To prevent funds from displaying only the most favorable numbers, the SEC strictly defines the return data to be included. As a general rule, the summary prospectus must show annualized return for the past 1, 5, and 10 years (or since the startup of the fund if it has been around for less than 10 years). The calculation must be done in three different ways:

1. Showing the effect of sales loads only, if there are any

2. After sales loads and taxes on distributions

3. After sales loads, taxes on distributions, and taxes on sale of fund shares3

The return figure used is always total return, which is defined in “Adding Up Return.” A detailed description of the calculations is available on the web site that accompanies this book.

ADDING UP RETURN

Even though mutual funds come in a variety of flavors, their results are all evaluated using the same measurement: total return, which incorporates all the elements of return—both income and price appreciation—in one computation. For mutual funds, total return includes:

- Interest and dividend income, minus the annual operating expenses. As we learned in Chapter 2, this income must be distributed to shareholders annually.

- Realized gains or losses on securities that have been sold already, which must also distributed annually.

- Unrealized gains or losses on securities still held in the portfolio. These gains and losses are reflected in the fund’s NAV.

To help buyers put these return numbers in context, the fund must also provide the return of an appropriate market index for the same periods. We talk in depth about the value of this type of comparative analysis in the next chapter.

Section 5: Management. Here, the summary prospectus names names. It’s at this point that we’re given the name of the company managing the investments—which isn’t always the company on the front cover of the prospectus. We also learn the names of the portfolio managers—who are the specific individuals at that firm who are responsible for buy and sell decisions—and we find out how long they’ve been managing the fund. (This information is not required for money market funds). Mutual fund cognoscenti keep a close watch for amendments to this section, since a change in portfolio manager can sometimes mean a significant change in investment approach.

Section 6: Purchase and sale of fund shares. For investors who are still interested in the fund, this section gives an overview of how to buy or sell fund shares. Some funds may offer only one option, but many present a whole menu of ways to invest, which could include:

- Through a broker or other financial representative

- Through a systematic investment program, making regular deductions from a checking or savings account or a paycheck

- Through the Internet

- By phone

- By mail

- By wire transfer

Minimum investment amounts are discussed here, along with basic information on redeeming your shares, such as how the proceeds of a sale will be paid to you.

Section 7: Tax information. For those unfamiliar with how a mutual fund works, the summary prospectus explains that the fund will distribute its income every year and that shareholders may have to pay taxes on those distributions.

Section 8: Financial intermediary compensation. The summary pro-spectus ends with another discussion of costs. (It should be obvious by now that the SEC wants disclosure in this area to be crystal clear.) If a fund—or its adviser and or an affiliate—pays intermediaries, such as brokerage firms, to sell its shares or to provide services to investors, it must declare that:

These payments may create a conflict of interest by influencing the broker-dealer or other intermediary and your salesperson to recommend the fund over another investment.

And that’s it. All other information must go into either the statutory prospectus or the statement of additional information; it can’t be added here.

BEYOND THE SUMMARY PROSPECTUS

Some potential buyers want more detail than the summary prospectus provides. Funds prepare the full prospectus and statement of additional information for them. Investors who already own shares need regular updates on how the fund is faring, which they can find in the semiannual shareholder reports. Let’s take a closer look at these documents. Samples are posted on this book’s web site.

Prospectus

Until March 2009, the full, or statutory, prospectus was the document that all mutual funds sent to buyers. It had been carefully designed to include all material information that investors needed to know before diving into a mutual fund.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t a lot of evidence that investors actually read the full prospectus. In fact, a 2006 survey conducted by the Investment Company Institute found that only one-third of fund investors had consulted the fund prospectus before investing.4 Recommendations from financial advisers were much more likely to influence decisions.

PAPERBACK WRITING

The fund prospectuses that arrive in a fund owner’s mailbox can rival a paperback novel in weight and page count. The statutory prospectus for even a single fund can run to 40-plus pages if formatted in a reader-friendly way. And adding to the weight of the documents—literally— fund families often present several related funds together in the same prospectus. This saves on printing, mailing, and legal fees, but does little to prevent shareholders from being overwhelmed by excess information.

To cut back on the deluge of information, the SEC has decreed that the summary prospectus must stand on its own: it may contain information about only one fund.

The sheer quantity of information included in the prospectus seemed to be part of the problem. The same ICI survey found that about two-thirds of shareholders thought the prospectus contained too much information and was difficult to get through. And despite the SEC’s best efforts to make the language in it understandable, one professor of English termed it unreadable.5 Given all the criticisms, many industry observers began to endorse the idea of a shorter document that made key information more accessible. (See “Paperback Writing” for more on the sheer weight of prospectuses.)

Concluding that there must be a better way, the SEC created the summary prospectus and offered funds a choice. Beginning in March 2009, they could send either the full prospectus or the summary prospectus to buyers. If they opted for the latter, they would have to post on their web site all the documents we discuss in this chapter: the summary prospectus, the statutory prospectus, the statement of additional information and the fund’s most recent annual and semiannual reports. And they would have to make sure that investors could easily navigate both within and among these online documents, using tools like a table of contents or links.

Since most funds already posted key documents online, moving to the summary prospectus offered substantial savings on printing and mailing costs. In fact, by April 2010, a little over a year after its endorsement by the SEC, more than 4,300 standalone summary prospectuses had been filed, according to NewRiver, Inc. which has tracked the filing data.6

Still, the statutory prospectus has its adherents. It necessarily includes more information than the summary prospectus for the simple reason that it includes the summary prospectus in full—as its leading section. The balance of the statutory prospectus contains:

- More detail on investment strategies and risks.

- Information on the time the fund calculates its NAV, which is usually right after the New York Stock Exchange closes. Investors need to have their buy or sell order in before that time if they’d like them to be processed on the same day.

- Specifics about limits on transactions by fund shareholders, especially short-term trading. Funds discourage investors from buying and selling fund shares frequently, since it imposes costs on all the owners of the fund but benefits only a few.

- All the nitty-gritty detail on sales charges.

- A financial highlights table, with data on NAV, returns, and expenses in each of the past five years.

If a fund wants to put an attractive outside cover, or wrapper, around the prospectus, it must prevent any confusion by including the disclaimer that “This page is not part of the prospectus.” For the guidelines on the content of these wrappers and other fund promotional material, see “Truth in Advertising.”

TRUTH IN ADVERTISING

While the SEC wants investors to use the prospectus as their sole source of fund information, many potential buyers are first exposed to a fund through an advertisement. Fund management companies advertise heavily to attract assets to their funds.

Like every other aspect of the mutual fund business, investment company advertising is strictly regulated. And it’s not just conventional TV, radio, or print ads that are subject to controls. Restrictions apply to anything a fund distributor sends out to promote itself or its fund offerings, whether a sales brochure or even the reprint of an article appearing in the Wall Street Journal. This includes a firm’s entire Internet presence, from its web site to blog posts to messages left on social networking sites.

Fund distributors must file every last bit of this material with FINRA within 10 business days of its first use.7 (For an overview of this self-regulatory organization, refer back to Chapter 1.) FINRA reviews all submissions to determine if they are fair and balanced and provide a sound basis for evaluating the fund. In addition, materials may not include any “false, exaggerated, unwarranted or misleading statement or claim” or any predictions about future performance.8 Ads promoting a particular fund must also refer the reader to the prospectus. If the FINRA reviewer finds shortcomings with the material, she may suggest changes, require revisions, or, in the case of serious deficiencies, issue a “Do Not Use” letter that calls for a written response from the fund distributor.

While a few ads are designed to build brand and do not include any numbers, most focus on fund performance and are, therefore, subject to particularly stringent standards set by the SEC. As in the prospectus, management companies have no choice about which numbers to present. If they want to include performance information at all, they must show data for 1, 5, and 10 years (or since inception if the fund has been in existence for less than 10 years) as of the most current quarter end. And these ads must always remind investors that:

Past performance does not guarantee future results.

So, fund ads are accurate, but are they useful in making a decision about a future investment? Remember that fund management companies are not required to publish ads; it’s something they do only when they believe they’ll increase fund sales. And that’s usually when the fund has been doing particularly well, either because of astute choices by the fund’s portfolio manager or strong gains in the types of securities the fund holds or both. But that’s not necessarily the best time for making an investment in that fund. At the same time, ads don’t include the full discussion of risk and expenses that investors can find in the required disclosure documents.

Best to follow the advice that at the bottom of almost all fund ads, and:

Read and consider the prospectus carefully before investing.

Statement of Additional Information

Some investors scoff at the idea that the prospectus is too detailed—they argue that it’s not detailed enough: the statement of additional information is the fund document geared for this group. It’s a small audience, though—so small that one large mailing house, serving many fund families, reported that investors had requested a total of six SAIs over the course of one calendar year. Because of the limited demand, funds are not required to provide SAIs unless someone specifically asks for them. These days, most fund families make them available on their web sites—and remember that they must make SAIs available online if they send out the summary prospectus as a standalone document.

While the SEC has, as usual, established detailed guidelines for the SAI, in practice, funds include everything in it that they believe some investors might want to know. For example, many funds provide additional detail on how portfolio securities are valued, even though this is not specifically required by the SEC.

Much of the SAI tends to be legal boilerplate, included to make sure that the fund has disclosed absolutely everything to the investor. For example, the list of investment strategies will normally describe every transaction that the fund might possibly engage in during the year, whether they’ll use those strategies regularly or not. Then there’s the list of things the fund may not do, called investment restrictions. These are usually mandated by law and apply to all funds.

There is not much in any of these sections to distinguish one fund from another. There are, however, important pieces of information in the SAI. Among them are:

- Board of directors. The SAI provides the detail that helps investors assess how well the board members’ interests are aligned with their own. We learn specifics about the directors’ occupations, the other boards they sit on currently or have served on in the past five years, the compensation they receive from this fund specifically and from all the funds in the fund family combined, their ownership of shares in this fund and other funds in the family, and their financial transactions with the fund management company. More generally, the board must explain why each of the directors is qualified to serve on the board at this time. (Refer back to Chapter 2 for a review of the ongoing debate about fund directors.)

This section also provides insights into the board’s inner workings. There’s a description of the leadership structure: whether the chair of the board is an interested or disinterested director or whether there’s a designated lead independent director. The fund must also explain the board’s role overseeing risk management—a critical issue for investors.

These disclosures about boards are not unique to mutual funds; the SEC requires them of all publicly held corporations. Missed them in the SAI? They are also included in the proxy statement prepared whenever there is a shareholder vote. - Portfolio managers. Here investors can learn more about the individuals making investment decisions for the fund. The SAI gives details on how many other accounts they manage—both mutual fund and non-mutual fund— which is relevant because those accounts may compete for the manager’s time, attention, and best investment ideas. It provides a description of the methodology used to determine the manager’s compensation (though not the actual dollar amount) and the amount of the portfolio manager’s ownership of the fund’s shares, if any. As with the section on members of the board, investors are being given information that helps them assess whether the portfolio managers’ interests align with their own.

- Contracts. The fund must describe the contracts for services it has signed. This discussion is useful for understanding the fund’s expense structure and for identifying any potential conflicts of interest.

- History. If the fund has changed its name, it must mention that here—important for anyone tracking down an old fund position. The SAI also discloses any tax-loss carryforwards; these are net losses on securities sold in prior years. (They may appear in the fund’s annual report as well.) Loss carryforwards will reduce the taxes on any gains taken this year, so information on them is valuable to investors.

Shareholder Reports

The disclosure of important information doesn’t end once an individual has bought fund shares. Funds keep their shareholders up to date by providing them with at least two reports every year, the semiannual and annual shareholder reports.9 These reports give investors the information they need to evaluate both whether the fund has met their expectations and whether it should continue to be part of their financial plan in the future.

At the most basic level, the shareholder reports update the key information provided in the prospectus to reflect the most current data. They include expense and performance numbers, although they’re presented a bit differently here than in the other disclosure documents. For example, past performance is displayed in a line graph as well as presented in a table. All very helpful, but not particularly new information.

It’s the narrative discussion of the raw data that makes these periodic reports especially useful to shareholders.

Portfolio commentary. The most important part of a shareholder report is the commentary from the fund’s portfolio manager, usually in the form of a letter or an interview. Here the manager discusses how well—or poorly—the fund did over the period being covered compared to both a relevant market index and to similar mutual funds. The review highlights the investment decisions that had the biggest impact on that performance, both positive and negative, and any major changes that were made in the portfolio over the period. The portfolio commentary normally ends with a discussion of the future—a very rare item indeed in a fund’s disclosure documents. The manager will review, in broad terms, his outlook for the relevant markets and explain how the fund is positioned to profit from the expected environment.

President’s letter. The shareholder report often includes a letter from the chief executive of the management company, covering nonportfolio issues that might affect shareholders. This letter might review changes in the executive suite at the management company or in the fund’s boardroom. If the fund management company has been involved in any mergers or acquisitions, this letter may describe the expected impact on investors. Or the president may explain how the fund might fit into a personal financial plan in the year ahead.

The quality of these letters varies widely. The weaker ones seem to be more interested in marketing than informing. But even then they’re an important source of the latest news.

Board discussion of contract renewal. Finally, in the annual report only, investors hear directly from the fund’s board of directors, which is required to explain why it signed a contract with the management company. Essentially, the independent directors are justifying the fee that they’ve agreed to. Most boards follow a template for this section, changing only the numbers from year to year and fund to fund. Despite its limitations, this material does give investors a sense of the factors that have come into play in the board’s conversations with management. (Turn back to Chapter 2 for a review of the Gartenberg standard that applies to those discussions.)

Two other elements of the shareholder reports are worth highlighting:

Holdings list. All funds (except money market funds) are required to include at least their top 50 holdings in their shareholder reports, although most include the full roster.10 Holdings are grouped by economic sector, geographic region, or other classification scheme appropriate to the fund.

Since the holdings list can be overwhelming—especially for a large fund—funds must include at least one graphic element summarizing the fund’s positioning. This could be, among other examples, a pie chart showing the percentages invested in stocks versus bonds or a bar graph showing the distribution of stocks by sector.

Financial statements. The income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows are included, though for mutual funds they’re called the statement of operations, statement of assets and liabilities, and statement of changes in net assets. They are audited once a year. The annual report will include a letter from the fund’s audit firm, describing their review and expressing their opinion on the accuracy of the financial statements.

USING THE USER GUIDES

So the fund’s disclosure documents contain a lot of information. What’s most important? When you’re beginning to research a fund, here are a few of the things to focus on:

- Investment objective. First turn to the prospectus or summary prospectus and the discussion of investment objective and strategy. Make sure that the investment approach matches your goals and fits well into your long-term plan for your portfolio.

- Risk. Staying with the prospectus, read through all the risk descriptions and assess the overall risk level of the fund. There are two ways to gauge this quickly: Number 1—if the fund has a fairly long history, look at the bar graph of annual returns to see the fund’s volatility. Less reliable, but still useful, especially within fund families, is Number 2— notice how much ink is devoted to describing the risks. The lawyers drafting prospectuses generally include more disclosure on funds they consider riskier within a fund family. These two factors combined allow you to begin to judge whether you’re comfortable with the expected level of risk.

- Sales load. If you think you’re still interested, study the table on expenses. Will you need to pay a front-end sales charge to invest in the fund? That might not make sense if you’re making all your own investment decisions, though it can be appropriate if you’re working with a financial adviser who is providing valuable advice. There are usually lots of rules in this section, but be sure to check them all out; you may be eligible for a reduced sales charge.

- Performance snapshot. Finally, take a quick look at the performance data. Overall, has performance been very good or very bad—or just mediocre? You’ll want to make sure you understand why … which leads to our next step.

- Performance analysis. Now you’re ready to take out the annual or semiannual report. Read through the portfolio commentary. Does the explanation of past performance make sense? Is it consistent with the performance numbers that have been presented and the list of holdings, as best you can determine? Pull up the management discussion and analysis in a shareholder report from a year or two previously—preferably from a time when performance wasn’t that great. You’ll want to make sure that the investment approach has been consistent over time. It’s particularly important to look back if the portfolio managers are new to the fund. (Remember that the prospectus will tell you about their tenure.)

- Portfolio manager investment. Next, turn to the statement of additional information and read about the qualifications of the portfolio team. Check whether the managers have invested their own money in the fund—it’s a good sign if they have.

Next, you’ll want to evaluate both performance and expenses compared to other funds. For this, you’ll need to turn to outside information sources. They’re the subject of our next chapter.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Mutual funds must comply with U.S. disclosure rules. They must register offerings of their shares with the SEC, provide buyers with a prospectus describing the investment, and then report periodically to owners about their investment. Funds usually provide three types of prospectuses: the summary prospectus, the statutory prospectus, and the statement of additional information. Each has a different level of detail. Investors can choose the prospectus type that best matches their informational needs.

The key disclosure document is the summary prospectus. It provides an overview of the funds’ investment objective and risks as well as the costs of owning the fund. It also gives potential investors information about the management of the fund, how to buy and sell fund shares, taxes associated with fund share ownership and compensation paid to intermediaries who sell the fund.

The statutory prospectus contains the summary prospectus in full. It also includes more information about the investment strategy and risks, the calculation of the fund NAV, sales charges and limits on purchases and sales of fund shares. Any other information that funds believe investors should know is placed in the statement of additional information. Details about the fund’s board of directors and portfolio managers can be found there.

Funds keep investors up to date by sending them at least two shareholder reports every year. These reports contain the latest statistics on the fund’s performance and expenses, together with a list of the fund’s holdings. Most importantly, these reports include the portfolio manager’s explanation of past returns and review his outlook for the future.

Investors considering a mutual fund investment can learn much of what they need to know about their potential purchase by reading these three types of disclosure documents. Fund advertisements are less complete. Most are designed to tout past performance, without an explanation of how that performance was achieved or whether it’s likely to continue.