Chapter 6

Portfolio Management of Bond Funds

In this chapter, we review the portfolio management of bond funds. These funds are also called fixed income funds, a name that refers to the relative predictability of the returns of the bonds held in the funds. Because the issuers of bonds are contractually obligated to make specified payments to investors on fixed dates, bond returns are generally more stable than stock returns.

This chapter reviews:

- The principal types of securities held in bond fund portfolios

- The main approaches to the portfolio management of bond funds

Note: Before you read on, please note that we assume throughout this discussion that you are familiar with how bonds work and are comfortable with fixed income terminology. If that’s not the case, you might want to turn first to the appendix to this chapter, which reviews bond basics.

BOND FUND HOLDINGS

Bond funds are divided into two major segments: taxable and tax-exempt. Taxable funds invest in a variety of bonds that pay interest subject to federal income tax, while tax-exempt funds invest in bonds issued by states and municipalities that are exempt from federal income taxes and sometimes state income taxes. This section reviews the types of securities that are often found in the portfolios of each category of bond fund.

Holdings in Taxable Bond Funds

As we saw in Chapter 4, taxable bond funds have a wide variety of investment objectives. Some funds have a very broad mandate to invest in many kinds of bonds, while others specialize in a particular type of bond or in a specific range of maturities: short, intermediate, or long term. All invest in one or more of the following different categories of bonds:

U.S. Treasuries. Treasuries are bonds issued and guaranteed by the U.S. government through the Department of the Treasury. They have maturities of up to 30 years and generally do not have call provisions (which are explained in the appendix). Because the United States is a wealthy country and the U.S. government has the power to tax its citizens to raise money to make interest and principal payments on these bonds, most investors consider Treasuries to be credit risk-free. They are, however, still subject to market risk and will fluctuate in value as interest rates change, with the degree of variability depending on their duration.

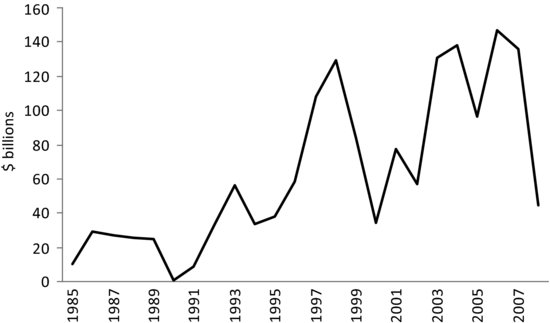

Treasuries accounted for about one-quarter of the U.S. bond market at the end of 2009, as shown in Figure 6.1.

FIGURE 6.1 Overview of the Taxable Bond Market

Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate Index

December 31, 2009

Maturity = 6.8 years1

YTM = 3.7 percent

Duration = 4.6

Source: Barclays Capital.

Agencies. Agency securities are the obligations of either federal government agencies or of government-sponsored enterprises, often referred to as GSEs. Major issuers of agency bonds are the Federal National Mortgage Association and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Association, better known as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, respectively. Agencies accounted for about 13 percent of the U.S. bond market in 2009.

Debt issued by GSEs, which are private corporations, is not guaranteed by the U.S. government. Even so, most investors still consider it to have minimal credit risk because they believe that the federal government will provide support for these issues should problems arise. That turned out to be true during the credit crisis in 2008, when the government assumed control of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which were both major mortgage lenders and experienced large losses when housing prices collapsed. While the government takeover validated the assumption of Treasury support, it also changed the agency landscape dramatically. Issuance of agency securities has fallen off sharply, as Congress debates the future of the home loan agencies.

Historically, agency debt has offered a slight yield premium over Treasuries. This yield advantage is not large, but does reflect the additional credit and liquidity risk of agency securities.

Mortgage-backed securities. Mortgage-backed securities, or MBS, are a collection of a large number of residential mortgages assembled together in a pool. Mortgages included in these pools must meet certain criteria with regard to size and quality. Similar to shareholders in mutual funds, investors in MBS own a proportional share of all the mortgages in the pool, which passes through the mortgage payments made by the homeowner to the bondholders. These payments are often guaranteed by a government agency or by a GSE—either Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac or possibly the Government National Mortgage Agency, known as Ginnie Mae.2 MBS are very popular: close to half of all mortgages in the United States are pooled in this fashion, creating a highly liquid market of high quality securities. MBS represented more than one-third of the U.S. bond market in 2009, making them an extremely important investment option for bond funds.

A distinguishing feature of MBS is that they have considerable call or prepayment risk. That’s because most homeowners can—and often do—pay off all or part of their mortgage at any time. If their mortgages are part of an MBS pool, those payments are passed on to the bondholders. Unfortunately, since homeowners are more likely to prepay their mortgage when interest rates are falling—and it makes sense to lower their costs by refinancing—that means that MBS holders will have to invest the cash received in lower-yielding securities. As a consequence, investors in MBS may find that their return falls short of what they originally expected. MBS holders try to manage this risk by using sophisticated models to quantify prepayment risk and estimate returns under various interest rate scenarios.

Asset-backed securities. Like MBS, asset-backed securities are also based on pools of debt, though usually without the guarantee of a government agency. The different types of ABS go by different names, depending on the nature of the underlying IOUs. Some of the varieties of ABS are:

- Traditional ABS, based on home equity loans, car loans, or credit card balances.

- Collateralized mortgage obligations, or CMOs, based on home mortgages. While many CMOs use loans that qualify for MBS, others package together mortgages that don’t qualify for inclusion in a mortgage pass-through, either because they are large (jumbo mortgages) or because they are of lower quality (subprime mortgages). A mortgage may be considered subprime if it was made to a borrower with a poor credit history, if it is large relative to the value of the home because the down payment was small (high loan-to-value), or if the borrower was not required to document his income (no doc, low doc, or Alt-A mortgages).

- Commercial mortgage-backed securities, or CMBS, based on mortgages made to businesses for commercial properties.

- Collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs, based on bank loans to businesses.

- Collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs, based on a variety of bonds including—believe it or not—other ABS. CDOs using subprime mortgage-backed securities played a significant role in the credit crisis.3

While these are some of the better-known types, ABS can be based on almost any type of debt. For example, the first ABS, issued in 1985, was backed by the credit that a computer manufacturer extended to its customers to enable them to purchase its equipment.4

ABS are an important part of the U.S. financial system, allowing banks and nonbank lenders to better manage their risk. Let’s take the example of a bank that has made a large number of car loans in a particular city and has decided that it has too much exposure to an economic downturn affecting the industries in that area. The bank would like to continue making loans there—rather than give their competitors a foothold in the market—but it would like to reduce its risk. The easiest way to do this is to sell the loans already on the books. Unfortunately, few investors have interest in buying the loans outright, since that would mean taking responsibility for collecting payment on and accounting for thousands of car loans. To get around this issue, the bank can securitize the loans by creating an ABS.

Unlike their mortgage-backed cousins, ABS are not pass-throughs, with a share-and-share-alike approach. Instead, ABS are structured securities which means that different investors in the pool can face different risk-and-return profiles, depending on the specific tranche (pronounced trawnch) they have purchased. Tranche is French for slice, or section, and each tranche in an ABS is entitled to a different slice of the risk and return. This tranching approach became a major factor contributing to the credit crisis, so let’s take a closer look at it.

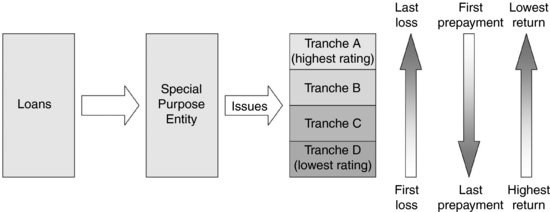

An ABS starts with a special purpose entity, or SPE—usually a trust or limited partnership—that holds a pool of loans or fixed income securities. The SPE generally issues several tranches of securities that are ranked from top to bottom. (There are single-tranche ABS, though these are less common.)

We’ll discuss an ABS with four tranches: Tranche A is at the top, while Tranche D is at the bottom. (See Figure 6.2 for a schematic of our hypothetical ABS, which explains why the structure of an ABS is often called a waterfall.) Tranche A is the senior tranche, while Tranche D is the junior tranche.

FIGURE 6.2 Structure of an ABS

Each tranche gets a different share of the income and losses. Tranche D is the riskiest. If there are losses on the underlying loans, Tranche D will take them first.5 Only after Tranche D has been extinguished—essentially wiped out—after absorbing all of the losses related to loans in the pool will Tranche C experience losses, and only after Tranche C has been extinguished by the next set of losses will Tranche B get hit, and so on. Because Tranche D is so risky, it is usually held by the financial institution that has created the ABS, or possibly by a hedge fund prepared to take that risk for a high potential return.6

Prepayments flow down in exactly the opposite direction. When borrowers on the underlying loans pay off their debt, the money goes first to Tranche A, then to Tranche B, then to Tranche C, and so on. This makes Tranche A the safest: because prepayments are allocated to them first, holders of this tranche have the best chance of seeing a return of their principal. (On the other hand, Tranche A will have considerable prepayment risk, but, as we’ve seen, investors will anticipate this risk and factor it into the return they demand from the tranche.)

Because Tranche A is the safest, it gets the highest credit rating and a lower share of the income produced by the underlying debt. Conversely, Tranche D will have the lowest credit rating—or maybe even no rating at all—and a higher share of the income.

However, if the pool of underlying loans is of poor quality and defaults in large numbers, it’s not just Tranche D that will suffer losses. This is what happened in the credit crisis, when even the most senior tranches of ABS, based on subprime mortgages, crumbled when housing prices collapsed.

These subprime mortgage ABS and CDOs had been the fastest-growing category of ABS in the years leading up to the credit crisis, a reflection of the surge in subprime mortgage issuance. In 2006, for example, over 39 percent of all new U.S. mortgage loans could be considered subprime, compared to about 9 percent only five years before.7 Analysts with little experience with these loans seriously underestimated the potential for defaults. Nowhere was this more true than at the credit rating agencies, which gave high ratings to the senior tranches of subprime ABS. (“Reforming the Credit Rating Agencies” reviews the proposals that have been made to prevent a repeat of the problem.)

In 2009, ABS accounted for less than 5 percent of the U.S. bond market—a decline in share resulting from the poor performance of recent issues and increased skepticism about the reliability of the credit ratings on new issues. Provisions in the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation may help reinvigorate the market and increase investor confidence in ABS by establishing new requirements for securitization. For example, the creators of a new ABS are now required, with some exceptions, to retain at least 5 percent of the risk of loss from the entire issue—an incentive to keep credit quality high.

Corporate bonds. Large corporations often issue bonds to finance ongoing operations or new acquisitions. Public utilities, transportation companies, industrials, telecommunication companies, banks, and finance companies are typical issuers. They issue bonds as an alternative to borrowing from banks, usually lowering their interest costs by going directly to investors. Corporate bonds make up almost one-fifth of the U.S. market.

REFORMING THE CREDIT RATING AGENCIES

The credit agencies’ broad misjudgments on securities based on subprime mortgages have generated some serious accusations—that the rating agencies were co-conspirators in the credit crisis—and other even more serious calls for change. The critics of the rating agencies have focused on their oligopoly status and their compensation model of issuer pays. Specifically:

Oligopoly status. The SEC and other financial industry regulators require the use of credit ratings for certain purposes. For example, as we see in the next chapter, money market funds must invest most of their assets in securities of the highest credit quality, as determined by a rating agency. Only a small group of rating agencies—technically known as nationally recognized statistical rating organizations, or NRSROs—have been recognized by the regulators. That has created an oligopoly with very limited competition, dominated by three firms: Fitch, Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s. While some critics want to eliminate credit ratings altogether, individual investors, state pension plans, and some insurance companies rely on them quite heavily.

“Issuer pays” compensation model. The major rating agencies are chosen and paid by bond issuers—not by the bond investors who rely on the ratings as an indication of quality. Since issuers want a high rating to make their bonds attractive to the public, this model encourages the agencies to go easy on companies in the hope of attracting their business. Critics even contend that issuers go “ratings shopping,” pitting the agencies against one other and choosing the one that is most likely to supply the highest rating. The agencies themselves counter that this is not the case and that they have strong internal processes that protect the integrity of the ratings process. In any event, the perception persists that agencies serve issuers more than they do investors.

Congress has addressed both of these concerns in the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010. The legislation directs regulators to remove many references to ratings in the federal statutes, thus reducing the rating agencies’ special status. It also directs the SEC, after conducting a study, to establish a mechanism to prevent bond ratings shopping.

All corporate bonds have a risk of default, so careful credit research is essential in this segment. This is particularly true for lower-rated, or junk, bonds, which are often considered a separate sector of the bond market. There are many funds that focus on junk bonds exclusively, and they appeal to many investors because of their fat yields. (See “Sorting through the Junk” for more detail on high-yield bonds, as they are often called.) With all corporate bonds—investment grade or junk—in addition to assessing default risk, analysts look for mispricings, meaning yield spreads that are too high or too low considering the expectations for the financial condition of the issuer

SORTING THROUGH THE JUNK

The high-yield bond market has changed significantly over the course of the past 30 years. In the 1970s, most junk bonds were fallen angels, formerly investment-grade issues that had fallen from grace. The companies that had issued these bonds had tumbled from the credit-rating heights when their businesses suffered serious setbacks.

In the 1980s, investors began to notice that past returns for diversified portfolios of lower-rated bonds were quite attractive, more than compensating for higher losses from defaults. They began to buy junk bonds in quantity, and it wasn’t long before demand for high-yield issues exceeded the supply of fallen angels. That left an opening for companies with below-investment-grade ratings to issue bonds, something they had generally not been able to do in the past. New issues poured into the market, visibly championed by the Drexel Burnham Lambert investment banker Michael Milken. Unfortunately, “junk” turned out to be an accurate characterization of many of the bonds issued during this boom period, and the high-yield market crashed at the end of the 1980s when many of these bonds defaulted.8

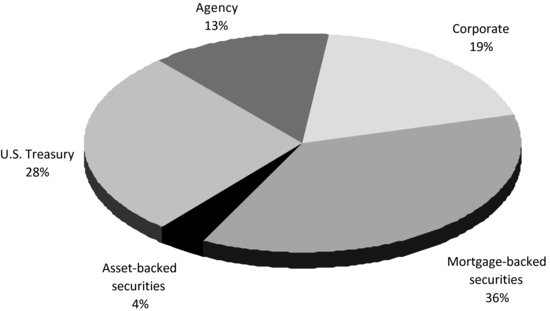

But the high-yield market survived the fallout and soon began to thrive again. Returns over the past 20 years have been attractive, although very volatile, and more often correlated with the returns of stocks than those of investment-grade bonds. Figure 6.3 shows the ups and downs of annual issuance of high-yield debt since 1985.

Non-U.S. bonds. As we’ve seen, many bond funds can invest outside the United States. If they do, they have a wide choice of bonds issued by foreign governments, international agencies, and companies incorporated in other countries. In some cases, these bonds are priced, or denominated, in U.S. dollars. Analysis of these Eurodollar, or Yankee bonds, as they are often called, is quite similar to that of U.S. bonds.9

However, most bonds issued outside the United States are not denominated in U.S. dollars. For these bonds, currency risk—the risk that the value of the foreign currency declines against the U.S. dollar—can be significant. Therefore, holding foreign currency bonds can add significantly to a portfolio’s volatility. We discuss the risks of cross-border investing in more detail in Chapter 16.

Derivatives. Derivatives are contracts that derive their value from an underlying security or group of securities. Many bond fund portfolio managers use them as a low-cost way to adjust a portfolio’s exposure to interest rate or credit risk. The most widely used fixed income derivatives are bond futures contracts, interest rate swaps, and credit default swaps. We discuss credit default swaps in more detail later in this chapter, but a comprehensive review of derivatives is beyond the scope of this book. For those who would like to do some reading on the topic, we have placed a brief bibliography on our web site.

Holdings in Tax-Exempt Funds

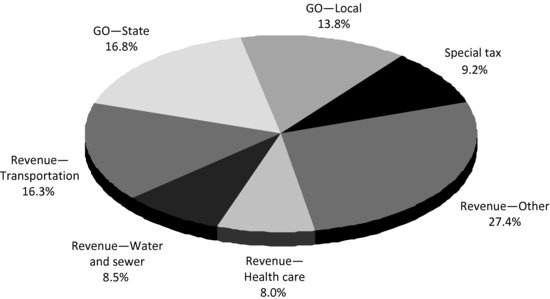

The tax-exempt, or municipal, bond market is less diversified than the taxable market. It is made up of only two basic types of bonds: general obligation bonds and revenue bonds. Figure 6.4 shows the breakdown of the U.S. municipal market.

FIGURE 6.4 Overview of the Tax-Exempt Bond Market

Barclays Capital U.S. Municipal Bond Index

December 31, 2009

Maturity = 13.5 years

Yield = 3.6 percent10

Duration = 8.3

Source: Barclays Capital.

General obligation bonds. General obligation bonds, often referred to as GOs, are issued by states and local governments (the latter are called municipalities) that pledge their taxing power to repay investors. This is a valuable promise, making GOs the least risky segment of the tax-exempt sector. Unlike Treasuries, however, they are not considered credit risk-free, and local issuers have defaulted on their obligations on occasion. As a result, investors make distinctions among tax-exempt issuers, requiring higher yields from those who are weaker financially. In 2009, GOs made up about one-third of the municipal bond market.

A separate category of debt issued by states and municipalities are special tax bonds, which are backed by revenue from a specific tax such as a gasoline tax. Since these bonds are not supported by the issuer’s general taxing power, they are not GOs, but their credit quality is still considered to be very high. They were about 9 percent of the tax-exempt bond market in 2009.

Revenue bonds. Revenue bonds, in contrast, do not have a claim on the government’s taxing power. They are issued to fund a specific project, and only the revenues associated with that project are available to repay investors. Revenue bonds may be used to finance the construction of water or sewer facilities, toll roads, hospitals, and municipal power plants, among other projects. They accounted for over half of the market in 2009.

Within revenue bonds, there are two subcategories:

1. Alternative minimum tax bonds. The interest from some revenue bonds is subject to the alternative minimum tax; these bonds are known as AMT bonds. The AMT was introduced in the late 1960s; it was designed to prevent wealthy taxpayers from lowering their tax bill to zero by taking advantage of the exemptions, credits, and deductions in the tax code—including the tax exemption on municipal bond interest. Not all revenue bonds are subject to the AMT—only those that are deemed private activity bonds because they are used to finance airports, stadiums, or other private-use facilities that do not have a clear public purpose. AMT bonds generally have higher yields than other revenue bonds, both because they are subject to the tax and because they are backed by projects that are more sensitive to the ups and downs of the economy.

2. High-yield municipal bonds. As in the taxable market, high-yield municipal bonds are those with lower credit ratings. Most are fallen angel revenue bonds, whose project revenues have fallen short of expectations.

Insured bonds. Even though most municipal bonds are considered quite secure, many state and local governments choose to increase the appeal of their bonds to investors by purchasing bond insurance. These policies, which are issued by specialized companies, guarantee repayment of interest and principal as it comes due. “The Faded Appeal of Municipal Bond Insurance” explains why this coverage was once very popular and why it’s no longer as common.

THE FADED APPEAL OF MUNICIPAL BOND INSURANCE

To understand the appeal of municipal bond insurance, let’s consider a bond with an underlying credit rating of single A. If the issuer purchases insurance, this bond’s rating jumps to AAA, which equals the rating of the insurer providing the protection. The rating upgrade appeals to buyers interested in reducing their risk. But the upgrade can make sense for the issuer, too—financial sense, that is. Higher-rated bonds can be issued with lower yields—meaning lower interest costs to the issuer. These cost savings are often more than the price of the insurance policy. Municipal bond insurance made so much sense to both buyers and issuers that, at its peak, in 2006, about half of all municipal issues were insured.

Insurance also made sense to the companies issuing the policies. In fact, because the default rate of municipal bonds is low, writing municipal bond insurance was a very profitable business. It was so stable and profitable that the insurers companies felt comfortable expanding into other areas. Unfortunately, many of their initiatives—which included forays into the subprime mortgage market—were badly hurt during the credit crisis. As these newer lines of business began accumulating huge losses, the municipal bond insurance market was thrown into turmoil. All of the insurers, including market leaders Ambac, FSA, and MBIA, suffered multiple credit rating downgrades, some to junk levels. As a result, the bonds they insured no longer automatically carried the all-important AAA rating. These downgrades, in turn, made insurance far less attractive to investors and issuers, and volumes fell off dramatically in consequence.

Pre-refunded bonds. One last category of municipal bonds: pre-refunded bonds, often referred to as pre-res, which are backed by a portfolio of U.S. Treasuries. Issuers generally can’t retire a municipal bond before its call date. Instead, to benefit from lower interest rates, the issuer buys enough Treasury bonds to cover all the remaining payments on the current bonds and then places the Treasuries into a separate escrow account, drawing on this account as needed to make those payments. The cash to buy the Treasuries comes from the issuance of another bond, often at a coupon rate lower than that of the bond that is being pre-refunded. The result is that the old bonds are defeased and taken off the books of the issuer—which is reasonable because the Treasuries are there to fund the payments on the bonds—while the new, lower-cost bonds remain outstanding. After-tax yields on pre-res are slightly higher than after-tax Treasury yields.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER: MANAGING A BOND FUND

So far, we’ve been talking about the many factors that any investor should consider when purchasing an individual bond. In this section, we review the challenges of selecting a portfolio of bonds that will achieve a fund’s objective. This task falls to the bond portfolio manager.

NOT ENTIRELY PASSIVE

While stock index funds have captured much of the limelight, bond index funds play an equally important, if less-heralded role for investors. As we reviewed in Chapter 4, passively managed funds look to match the return of a benchmark index. To do this, portfolio manager sometimes simply replicate the index by buying investments in the same proportions as their representation in the relevant benchmark.

That’s easy in theory, but next to impossible in practice—at least for bond indexes, which contain an extremely high number of securities. A taxable bond index can include thousands of issues, and the number rises into the millions for some tax-exempt benchmarks!

As a result, bond index managers generally use sampling techniques that seek to match the return of an index while holding only a portion of its securities. They may start by eliminating the very smallest issues from consideration. Then they’ll use computer models to determine which bonds are likely to have very similar or homogeneous returns, then choose only a few representative bonds from that group. In this latter step, they may incorporate some of the techniques used by active managers. For example, they may try to eliminate bonds with the highest call risk. Finally, they’ll look at the overall positioning of the portfolio they’ve selected to make sure that it aligns with index in regard to duration, yield curve exposure, overall credit quality, and other key characteristics.

Investment Strategy

The portfolio managers of bond funds use different strategies to produce a competitive total return. Some emphasize a big-picture, or top-down, approach, such as duration management, yield curve positioning or sector selection, while others work from the bottom up, focusing on credit analysis or on predicting calls or prepayments. We focus here on how these strategies are used by active managers, those who seek a total return that is higher than that of the benchmark index and ranks high in its peer group. By contrast, managers of bond index funds use only a few elements of these approaches when they attempt to replicate an index, as “Not Entirely Passive” explains.

Strategies for actively managing bond portfolios include:

- Duration management. Portfolio managers can dramatically influence the return of a bond portfolio by adjusting its sensitivity to anticipated interest rate movements, a practice commonly referred to as duration management or interest rate anticipation. This strategy involves altering the average duration of the fund based on the outlook for interest rates based on an assessment of the macroeconomic situation. If interest rates are expected to fall, portfolio managers buy longer duration bonds, which would benefit more from a decline in rates, while selling shorter duration bonds. Conversely, if portfolio managers expect yields to rise, they lower, or shorten up, their funds’ average duration.

The most obvious way to adjust the duration of a portfolio is to replace short duration bonds with longer ones or vice versa. This can be a very inefficient approach, however, especially when the bonds are difficult and costly to buy and sell. As a result, portfolio managers often modify a fund’s interest rate exposure by using a derivatives transaction, either a bond futures contract or an interest rate swap.

Duration management is a powerful performance tool. If a manager predicts the level of interest rates accurately and makes appropriate portfolio adjustments, her fund will likely beat the market handily. Unfortunately, predicting the direction of interest rates consistently is very difficult to do in practice. - Yield curve positioning. Portfolio managers may also try to predict shifts in the shape of the yield curve. The yield curve is constantly moving up and down, reflecting the change in the level of different interest rates. Sometimes all interest rates across the maturity spectrum will go up or down by the same amount; this is called a parallel shift in the yield curve. At other times, interest rates for different maturities change by different amounts. For example, if 30-year Treasury bonds are in particular demand, their yield may be less affected by a general rise in interest rates than the yield on 10-year Treasury notes. In other words, the yield on a 30-year bond will rise less than the yield on the 10-year note. In that circumstance, the yield curve is said to flatten. It steepens when short rates fall faster or rise more slowly than longer-term rates.

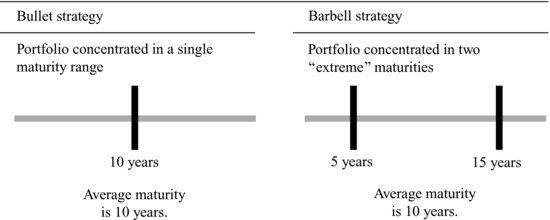

Portfolio managers can adjust the positioning of a portfolio to match their outlook for the yield curve shifts. If they anticipate that either short- or long-term rates will move without affecting the balance of the yield curve, they may opt for a bullet strategy, concentrating holdings in a narrow maturity range. If they think that the yield curve will steepen, they may use a barbell strategy, splitting the fund’s holding between longer or shorter durations. Figure 6.5 illustrates bullet and barbell portfolios.

FIGURE 6.5 Two Common Yield Curve Strategies

- Sector selection. With a sector selection strategy, the portfolio manager tries to take advantage of performance differences among the various bond market sectors. For example, the portfolio manager of a taxable bond fund who expects that the economy will get stronger may emphasize corporate bonds over U.S. Treasuries, while a tax-exempt manager might choose lower-rated bonds or revenue bonds in weaker states or cities. (Why? A stronger economy will likely lead to improved financial health of most companies and municipalities—which will reduce credit risk and, in turn, lead to lower yields and higher bond prices.)

All of the top-down strategies—duration management, yield curve positioning, and sector allocation—can have a significant impact on the relative performance of a bond fund. But success with all of these strategies—which often depends on accurately predicting economic trends—is difficult to accomplish consistently. As a result, many managers prefer to emphasize bottom-up strategies that focus on security selection, keeping duration and sector allocation close to that of the benchmark. - Credit selection. An important bottom-up strategy is credit selection, choosing bonds of certain issuers based on the outlook for their creditworthiness. To be successful with this approach, portfolio managers must be one step ahead of the market, identifying changes in a company’s financial condition not yet seen by other investors.

Again, the most obvious way to change credit exposure within a portfolio is to sell less-favored bonds and buy ones that appear to have brighter prospects. However, some portfolio managers use a derivative transaction—in this case called a credit default swap (described in “Popular, but Controversial”)—to accomplish the same thing.

POPULAR, BUT CONTROVERSIAL

A credit default swap is like an insurance policy: the buyer of the CDS pays a premium to a counterparty—usually a bank or a broker-dealer—to protect against credit risk on a bond. The policy pays off if the bond goes into default. They are a recent financial innovation, tracing their origins back only to the 1990s, and were initially used by banks with large corporate loan portfolios, which wanted to limit their exposure to borrowers facing potential financial difficulties. CDS allowed the bank to continue its relationship with a troubled corporation, while reducing or eliminating the cost of a potential default. The market for CDS has since expanded well beyond banks, as many investors have found them to be an effective tool to adjust credit risk exposure.

They have become so popular that, at their peak in 2008, the CDS market was many times the size of the actual corporate bond market! That had some advantages for investors. Given the breadth and depth of the market, CDS became a very good barometer of investor opinion regarding the outlook for a particular company. And they often provided an easier and cheaper way for portfolios to adjust credit exposures.

But the ballooning market raised more than a few eyebrows, as well. Market observers became concerned that CDS encouraged excessive speculation. That’s because it’s possible to buy a policy on a company even without owning the underlying bond. (This is the big difference between a CDS and a true insurance policy.) With the prospect of a big profit if the firm should go bankrupt, owners of a CDS had an incentive to bring about that very event by undermining public confidence in a company. Critics also pointed out that CDS involve substantial counterparty risk—the risk that the bank or broker-dealer providing the insurance would be unable to meet its obligations to policyholders. Unfortunately, their worst fears were realized when American International Group, also referred to as AIG, a substantial CDS counterparty, ran into financial trouble and could not pay its obligations to the parties on the other side of the CDS it had written. AIG was ultimately bailed out by the federal government to prevent its collapse from spreading to other firms.

In response, the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation mandates that most standardized derivatives be traded on an exchange or swap execution facility and settled through a clearing corporation. Writers of CDS will need to make margin deposits, marked to market daily, to ensure that they are able to fulfill their commitments to the buyers of the CDS.

- Predicting calls or prepayments. Managing the level of call or prepayment risk is another bottom-up approach. It’s especially important for MBS, which have a high prepayment risk. To assess this risk, portfolio managers use mathematical models to estimate the expected prepayments and to calculate the value of the imbedded call option based on that estimate. The manager then compares the value of the bond calculated by the model to its market price to determine whether the bond is a buy or a sell.

Portfolio Construction

In this section, we give you a chance to grapple with some of the challenges of managing a large bond fund. All of the investment strategies we’ve described can be used separately or in combination. Their implementation is within your province as portfolio manager, working on your own or as part of the portfolio management team. Your responsibility to the fund’s shareholders means that you have to manage the risks carefully, while doing everything you can to provide a competitive return. For more on the job of the bond portfolio manager, see the “Career Track” box.

CAREER TRACK: BOND PORTFOLIO MANAGER

Wonder what it’s like to be a bond portfolio manager? Here’s a scenario you might face on a typical day:

Your portfolio holds a large position in an exceptionally good corporate bond. It’s not a well-known company or bond, so it doesn’t trade often, and it has taken you the better part of a year to build the position with small purchases. A highly experienced credit analyst walks over and talks with you about their most recent report covering the issuer of this bond. The analyst says there’s a concern about a pending lawsuit that could have a devastating impact on the company.

You start weighing your options:

Option 1: Sell your position. To try to sell the entire amount of your holdings might move the market substantially, causing the price to drop considerably, because it’s a large position relative to normal trading activity. In further discussions with the analyst, you find that while an unfavorable outcome in the case could really hurt the company’s financials, maybe permanently, it’s not a likely scenario. If the lawsuit does not succeed, the company is expected to continue to do well.

Option 2: Do nothing. You could do nothing and just hope for the best. At this point, prices are stable, and the market doesn’t seem concerned yet with the lawsuit.

Option 3: Reduce risk. Or, you could think about using a credit default swap to hedge against a big decline in the bond. (See the explanation of these derivatives in the preceding callout box.) If the legal problems of the bond’s issuer are not yet widely known, the price of this insurance could be low.

To decide which option makes most sense, you’ll need to quantitatively estimate the results of each outcome, considering the likelihood of the success of the lawsuit, the potential impact on the bond price, and the cost of implementation of each outcome. And you’ll have to do it quickly, before other investors zero in on the same issue.

Assume that you’ve been put in charge of a multibillion-dollar taxable fund with a broad mandate to own investment-grade bonds of all types. Let’s think through some of the factors you’ll have to consider before buying a bond for the fund:

Prospectus objectives and restrictions. First and foremost, before buying any security, you’ll need to make sure that its selection complies with the guidelines set down in the prospectus. For example, if your prospectus states that the fund must invest at least 80 percent of its assets in high quality debt securities rated BBB or better, it’s your responsibility to ensure that actual purchases comply with that restriction. (See Chapter 3 for a more detailed discussion of the prospectus and the types of limitations it normally contains.)

Index. Next, you’ll need to know which benchmark index is being used for your fund. In this case, it’s the Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, which, like your fund, ranges across all sectors of the taxable bond market. You’ll study the details of the index, including its sector weightings, its constituent bonds, and its average yield and duration.

That’s because all of your positions will be evaluated relative to the index, which becomes your neutral position. If you’re positive on the outlook of a sector or a particular security, you’ll overweight it versus the index, meaning that its percentage weight in the portfolio will be higher than its weight in the index. Similarly, you’ll underweight sectors and securities when your opinion is less positive. But you probably won’t have a value-added idea every waking moment of every day. Therefore, when the ideas are in short supply, you’ll need to know how to keep the fund neutral to the index.

We’ll assume that you have studied the index and now know enough about how to neutralize the fund’s risks. Well done; it takes most portfolio managers months or years!

Peer group. You’ll also take a look at the peer group of competing funds that your fund is being compared against to see if you can learn anything from their strategies. (See Chapter 4 for a discussion of peer groups.) Peer groups and benchmark indexes are important for another reason: they’ll be the basis for your calculation of your bonus.

Duration management. Now it’s time to figure out which of the strategies fit with the strengths of your firm and your experience. The biggest question you’ll face is how much emphasis to place on top-down strategies. Most managers of large bond funds have decided that using an interest rate anticipation, or market timing, strategy exclusively is not a winning approach over the long run. All bond managers can talk about a few times when they made a large shift in duration that served the portfolio and shareholders well, but they usually have an equal number of stories—not as well publicized—about times when a shift in duration hurt returns. But if you deemphasize the most powerful tool available to a bond portfolio manager, how will you focus your efforts?

Yield curve positioning. You can turn to a team of analysts armed with computer models to help you sort through the decisions regarding yield curve shape. You’ll need to figure out where to own securities along the time line of the yield curve. Do you want the portfolio to be more of a bullet or a more of a barbell? And once you settle on your ideal positioning, implementing your decision is quite complicated in practice, very much interconnected with sector and credit choices. Certain securities lend themselves to certain positions on the curve. For example, mortgages tend to have intermediate durations because of a high probability of prepayment, whereas utility bonds tend to be longer term since they use the proceeds from bond sales to finance plant construction. Therefore, your choice of how to invest along the yield curve will influence the types of securities that may be available to the portfolio and vice versa.

Sector. Recognizing the impact of the yield curve decisions, you’ll need to think more about the sectors that make the most sense for the portfolio. Do mortgages make sense? Do market prices reflect the levels of prepayments predicted in your modeling? Should you over- or underweight corporate bonds? Is the economy improving or deteriorating, and how will that affect corporate bond prices? And which industries within the corporate market will perform the best? There are lots of questions to sort through to invest in the right sectors and industries. For example, it wouldn’t make much sense to find the best bond issued by an insurance company if the whole industry is under pressure. If one insurer’s bonds are priced cheaply enough, they might still be a buy, but you have to own them recognizing that there is downside risk for the industry as a whole.

Credit. At the same time, you’ll be working with the credit analysts to identify which securities represent the best values at the points on the yield curve and in the sectors that you are trying to emphasize. The credit analysts will let you know which bonds are most attractive, maybe because the issuers are stable or even improving financially—or maybe because they’re priced right even if the issuer’s prospects are deteriorating slightly. Once you start to narrow down the list, you’ll need to decide which specific bond is best. In most cases, large corporate issuers will have many bonds outstanding. Choosing between a four-year or five-year bond of the same issuer if only one has a call option attached is when the process gets most interesting. All of the skills of the investment team will be needed to evaluate trade-offs in order to arrive at a final decision.

Liquidity and trading. Once your security selections are made, you’ll need to consider your ability to actually buy them in your portfolio. Unfortunately, many corporate bonds trade in small amounts and can be costly to buy and sell. You’ll work closely with your trading desk to actually implement your decisions. They’ll give you an overview of a market, look for the right securities at the right prices, and try to identify attractive bids for the bonds in the portfolio that may no longer make sense to hold.

The dialogue among the traders, the analysts, and you needs to be constant. It’s a dynamic process, particularly given that you are managing a multibillion-dollar fund with hundreds of positions together with daily inflows and outflows as shareholders purchase or redeem fund shares. We discuss bond trading in more detail in Chapter 8.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Taxable bond funds invest in securities issued by the U.S. Treasury, by government agencies and government-sponsored enterprises, by U.S. corporations, and by non-U.S. governments and corporations. The credit quality of these issues can vary widely. U.S. Treasuries are considered credit risk-free, while high-yield, or junk, bonds have considerable default risk.

Taxable bond funds may also invest in mortgage-backed or asset-backed securities—which are backed by a pool of loans or other fixed-income securities. Mortgage-backed securities act much like a mutual fund, passing through payments of interest and principal to the bondholder. In contrast, asset-backed, or structured, securities are divided into a series of tranches. Each tranche receives a different share of the income and the losses from the underlying pool of securities.

The tax-exempt bond market is composed of two types of bonds: general obligation bonds and revenue bonds. General obligation bonds, or GOs, are issued by state and local governments that pledge their taxing power to repay investors. GOs are considered to have very high credit quality. Revenue bonds are riskier because they can be repaid only from the income generated by a particular public project, such as a water or sewer facility constructed using the money raised from the bond offering. Certain revenue bonds may also be subject to the alternative minimum tax. Both GOs and revenue bonds may be insured or pre-refunded.

Bond fund portfolio managers use various strategies to choose securities for their funds. Bond index fund management involves some active elements; that’s because most bond indexes contain a large number of securities, which means that passive managers almost always use sampling techniques to try to match index performance. Active managers use a wider range of bond selection strategies. They may use a top-down approach and try to anticipate changes in interest rates or the relative returns of different types of bonds. While these big-picture strategies can have a significant impact on fund returns, they are very difficult to get right consistently. As a result, many bond fund managers use bottom-up strategies that focus on selecting specific securities by using credit analysis or predicting calls or prepayments.

Portfolio managers work closely with bond traders to implement buy and sell decisions. They often use derivatives transactions, such as credit default swaps, to reduce the transaction costs of implementing those decisions.