Chapter 8

Implementing Portfolio Decisions: Buying and Selling Investments

For mutual funds, trading, or buying and selling investments, is a critical final step in an integrated investment process that starts with research and carries through to portfolio construction. Here, we discuss how the decisions made in those first two steps are implemented through trading. Our focus is trading in stocks, although at the end of the chapter we outline how fixed income trading compares to equity trading.

Executing buy and sell orders is the province of the trader. Most larger investment managers have a trading division, or desk, that is separate from the portfolio management function. (At smaller advisers, portfolio managers may handle their own trading.) This division of labor allows the portfolio managers to concentrate on their primary task of selecting securities and structuring portfolios, normally with a time horizon measured in months or years. That, in turn, enables the traders to focus on the dynamics of the market, to gauge the appropriate day, hour, or even minute for completing a transaction. Separating the trading function from portfolio management has another benefit: it gets a second set of eyes involved in every transaction, which helps to ensure that a fund complies with all regulatory requirements.

The execution of trades is far from a mechanical process. It calls for close collaboration between portfolio managers and trading desks. Decisions on how, where, and when to send in trading orders require careful judgment, long experience, and intimate knowledge of the trading markets. Well-planned trading decisions can contribute significantly to a fund’s investment returns.

This chapter reviews:

- The importance of the trading function to investment returns

- The evolution of stock trading in the United States

- The role of the stock trading desk

- Trading in bond funds

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADING

Trading in either stocks or bonds can have a significant impact on fund performance. One influential academic study done in 1999 found that trading reduced returns in stock funds by almost 0.8 percent per year on average.1 Fund managers today, with more choices open to them, work hard to push down transaction costs as much as possible, by using sophisticated trading techniques.

Yet, because funds often buy and sell securities in large amounts, they face considerable challenges when they trade, including:

- Front running. Other market players might learn about a fund’s trading plans before they’re fully carried out. If advance information about a fund’s intentions becomes known to other traders, those traders can use that information to their advantage and a fund’s disadvantage. For example, if traders learn that a fund is trying to acquire a large block of stock when the stock is trading at $10 per share, they might pay up a few cents to purchase the stock at $10.03, on the expectation that the fund will be willing to pay an even higher price to complete its purchase. This is called front running.

- Market impact. Even when other market participants are unaware of a fund’s trading plans, the large size of a fund’s purchases and sales alone can move the market in a stock—pushing up the price of a stock a mutual fund is trying to buy and driving down the price of a stock a fund is seeking to sell. This market impact is a particular issue for small cap stocks and other less-liquid securities in thin markets, which are markets with a low volume of trading.

- Opportunity cost. But there’s another, countervailing risk: a fund that moves too slowly can incur an opportunity cost. It might miss out on a sharp increase in the price of a stock it’s trying to buy or watch the price of a stock it’s trying to sell tumble after bad news is announced.

A fund trading desk must weigh the relative importance of:

- Obtaining the most favorable price

- Protecting a fund’s anonymity

- Obtaining a speedy execution

- Minimizing transaction costs

Trading decisions invariably call for the exercise of judgment in awarding greater weight to one factor over the others—and striking trade-offs when one trading goal must be sacrificed so that a more important one can be achieved. For example, a fund manager might be trying to acquire a substantial position in a thinly traded small cap stock or a less well-known bond. Recognizing the potential for market impact under these circumstances, the trading desk might break up an order and patiently purchase small, incremental amounts over the course of one or more trading days. The traders, in consultation with the portfolio manager, might decide that the need for anonymity trumps the desirability of gaining a speedy execution.

In another case, a fund manager, acting on input from an investment research analyst, might want to quickly sell a substantial position in a stock out of concern that the company will suffer a sharp drop in earnings for the quarter that is coming to a close. Under these circumstances, the trading desk might decide to move quickly, accepting a less attractive price for the entire block of stock. The traders, in the interest of speed, would forego attempts to do better by selling the stock piecemeal over the course of the trading day.

To begin to understand how traders make these types of decisions, we’ll need to start by studying the securities markets. We’ll be zeroing in on the U.S. stock markets, returning to bond trading only at the end of the chapter.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE U.S. STOCK MARKETS

Stock trading in the United States has been radically transformed by technology in recent years. Innovations in computer systems and high speed data communications have led to a complete change in the way that larger investors buy and sell stocks. As a result of this new technology, trading has spread from traditional venues like the New York Stock Exchange to a variety of trading centers as securities markets have become more electronic. This radical change in market structure has taken place within the context of dramatically increasing trading activity. On the NYSE alone, average daily stock trading volume rose from 2.1 billion shares in 2005 to about 5.9 billion shares in the first part of 2009, a growth rate of almost 30 percent per year.2

In this section, we take a closer look at how the U.S. stock markets have evolved. We first describe the traditional market structure, centered on the NYSE and NASDAQ, and then turn to the new entrants. Finally, we examine how the old and the new are converging.

The Traditional Venues

Until very recently, there were two principal ways to trade stocks in the United States: on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange or over the counter on the NASDAQ exchange, both operating within the national market system.

New York Stock Exchange. For over a century, the NYSE (pronounced by spelling out each of its four letters) was synonymous with the financial business. Its location on Wall Street even gave the securities industry its nickname. Most major U.S. corporations listed on the NYSE, meaning that they made their stock available for trading there. In exchange for the privilege of inclusion on the exchange’s roster, they agreed to adhere to certain standards regarding their financial condition and internal policies. In 2005, 85 percent of the trading in the shares of companies listed on the NYSE took place there.

Until very recently, trading on the NYSE took place literally on the floor of the exchange, in face-to-face dealings. A broker, on behalf of a customer wanting to buy stock, would seek another broker representing a customer wanting to sell the same stock. The broker would be paid a fee per share, called a commission, for this service.

Brokers for buyers and brokers for sellers would meet at the specialist’s post. The specialist was an NYSE member assigned to a particular stock, such as ExxonMobil or IBM. What did specialist firms do?

- They served as auctioneers—soliciting offers to buy (called bids) and offers to sell (called offers, or asks) from brokers representing their customers in the trading crowd.

- They matched buyers and sellers who reached agreement on price and amount.

- They maintained a book of limit orders, which are bids and offers away from a stock’s current market price and arranged for execution of the orders whenever the market price moved to the limit price.

- They used their own capital to reduce imbalances between buying and selling interest, by buying when others were selling and selling when others were buying.

“Making Your Best Offer” explains trading terminology.

NASDAQ exchange.3 Beginning in the 1970s, at the advent of the computer era, a second major stock market emerged. Rather than granting a monopoly to a single firm to act as a specialist in a stock, NASDAQ (Naz-dack) allows all brokerage firms that meet certain requirements to make a market in any stock listed on the exchange by posting bids and offers.4 Customers who want to trade a stock on NASDAQ buy or sell from one of these market makers. Trading that takes place in this way is said to occur in the over the counter, or OTC, market.

MAKING YOUR BEST OFFER

When a securities trader goes to buy a house, she makes a bid, not an offer. That’s because traders are very particular about the language they use when making a purchase or sale. When traders want to buy a stock, they make a bid, which is a proposal to purchase a certain number of shares at a particular price. Similarly, they make an offer, or ask, when they propose to sell shares at a price.

Different traders will have different bids and offers. Let’s see how this works in the hypothetical market for Netherfield stock. Three traders are interested in buying and selling. Table 8.1 shows their bids and offers.

TABLE 8.1 The Market for Netherfield Stock

| Trader | Bid (per share for 100 shares) | Offer (per share for 100 shares) |

| Elizabeth | $23.00 | $24.50 |

| Jane | $23.50 | $24.25 |

| Charles | $23.25 | $23.75 |

Jane is willing to pay the highest price to buy Netherfield shares. Therefore, her bid of $23.50 is the best bid. Charles, on the other hand, has the lowest sale, or offer, price of $23.75; this is the best offer, or best ask.

The difference between the best bid and the best offer is the spread. It is the cost of transacting immediately. For example, if Jane decides that she wants to buy 100 shares right now, she’ll need to pay $23.75 or 25 cents per share more than the bid. The spread represents a profit to the specialist, or market maker, who supplies the liquidity to enable Jane to complete her trade. Spreads are generally bigger, or wider, for stocks that are riskier or less liquid; they are smaller, or narrower, for stocks that are actively traded or whose prices remain fairly stable.

An order to buy at the best offer or sell at the best bid is called a market order. Jane placed a market order when she decided to buy at $23.75. Limit orders are placed away from the best bid and offer. For example, Elizabeth has placed a limit order to sell 100 shares at $24.50, which is above the best offer of $23.75.

The computer-based nature of the NASDAQ market has appealed to many technology companies, which decided to make their shares available for trading on it rather than on the NYSE. Some of the world’s largest companies, including Google and Microsoft, are listed on NASDAQ.

National market system. The national market system tied the NYSE and NASDAQ to each other, as well as to other smaller stock exchanges.5 Congress called for the SEC to create the national market system in 1975 so it could advance, among other things:

- Efficient execution of trades

- Fair competition among broker-dealers and among markets

- Widespread public availability of current information on stock trades

Two of the key elements of the national market system are the consolidated transaction reporting and consolidated quotation rules. The first is often called the consolidated tape rule, after the ticker tape that was used in the telegraph era to record stock prices. It requires that the price and size of all stock trades—made on any exchange or trading center—be fed immediately into one consolidated, electronic reporting system and be made publicly available.

Similarly, the consolidated quotation rule requires that the price levels and amounts of bids and offers in stocks be fed into an electronic data processing system and that all market participants have access to these quotes.6 The information is further consolidated to arrive at a national best bid and offer, or NBBO, for each stock.

One of the key features of both rules is that the data collected be made available to everyone—broker-dealers, specialists, market makers, and investors alike—enabling all market participants to make informed trading decisions. But note that the dissemination of the information has not been entirely symmetrical. Historically, specialists collected limit bids and offers from customers that they were not required to disclose. This gave them a more detailed view of the depth of the market for a particular stock—and, therefore, a potential trading advantage over the customers who supplied them with that information. The same has been true for firms that act as market makers and accept limit orders from their customers.

The New Entrants: Alternative Trading Systems

In the 1990s, advances in computer technology and high speed telecommunications paved the way for new competition to the NYSE and NASDAQ. Known as alternative trading systems, or ATS, these automated electronic trading platforms enable investors to trade anonymously with each other—allowing them to maintain control of information on their trading intentions, information that they formerly ceded to the specialists and market makers. Unlike the NYSE or NASDAQ, ATS don’t enter into arrangements with issuers to list their stocks. Nevertheless, essentially all of the actively traded stocks listed on the NYSE or NASDAQ are now traded on at least one ATS.

The growth of ATS was given a tremendous boost when the SEC adopted the trade through, or trade protection, rule in 2005. In short, this rule requires a broker to send a customer’s market order to the exchange or ATS that is quoting the highest bid or the lowest offer—as long as it has a fast market, meaning that it uses electronic trading. Once the rule came into effect, brokers could no longer automatically route customers’ market orders for NYSE-listed stocks to the NYSE, as they often did in the past. The rule had a huge impact: it led the NYSE to try to keep up with NASDAQ and the ATS by dropping its historic floor-based trading model and developing a hybrid system that includes purely electronic trading. “Counting the Pennies” reviews another SEC regulation that also significantly changed stock trading.

COUNTING THE PENNIES

Another factor that has shaped the equity trading markets has been the change to decimal pricing of stocks. Historically, bids and offers would be in ⅛s, equal to one-eighth of a dollar or 12.5 cents. For example, the national best bid and offer for a stock might be 10⅛ bid and 10⅛ offered, for a spread of ¼. That translated to $10.125 and $10.375, for a spread of 25 cents. One of the first things that new traders had to learn was the value of these fractions.

But as technology made the stock market more efficient, a spread of 12.5 cents—the lowest spread possible when pricing in ⅛s—was just too high. So in 1997, pricing increments were reduced for some stocks to increments of one-sixteenth of a dollar or 6.25 cents, known to traders as teenies.

Finally, beginning in 2000, the SEC ordered that stock prices be quoted in dollars and cents, so that an actively traded issue today can be quoted at $20.43 bid and $20.45 offer, for a spread of just 2 cents.

The changes have led to lower spreads, which have fallen from an average of around 12.5 cents in the mid-1990s to about 2.5 cents shortly after decimalization was introduced.7 That in turn has meant lower costs for investors—and much easier math for traders!

ATS have taken one of two forms: electronic communication networks and dark pools. Let’s look at each in turn.

Electronic communication networks. An electronic communication network, or ECN, allows any of its subscribers—whether a market maker, broker, or investor—to post bids and offers for specific amounts of stock. The ECN automatically matches buy and sell orders that are input at the same price. That’s a big cost advantage for investors, who no longer have to pay a spread to a market maker or a commission to a broker to get a trade done. Instead, investors just pay a fee for use of the network, which is much lower than a commission paid to a full service broker. Major ECNs include DirectEdge and BATS.8

ECNs address the information asymmetry that characterized traditional stock trading. In an ECN, subscribers are allowed to see the entire book—meaning all public bids and offers at all prices—so that they have the ability to evaluate the depth of the market for a particular stock for themselves. At the same time, participants don’t have to publicly display their bids or offers—some or all can be held in reserve to be used only if a matching trade should be input. That makes it easier for larger investors to buy and sell blocks of stock without affecting the market price.

For example, a mutual fund might wish to buy 25,000 shares in Northanger stock, but does not wish to tip its hand to the market. The fund sends in an order for 25,000 shares at $10 per share, but designates that only 500 shares be displayed on the ECN and that the rest of its order be kept in reserve as a resting order. If a seller hits the fund’s bid, by entering a sell order at $10 share, the ECN would automatically record a trade for 500 shares at $10 per share. It would then refresh the fund’s bid, posting a buy order for another 500 shares. In this way, the fund can work its purchases over the course of the trading day while reducing the chances that its total order for 25,000 shares would become known to the market and thereby push the stock’s price upward.

Dark pools. There is no single model for a dark pool. The term is broadly understood to describe any automated, electronic trading market that amasses hidden liquidity, in which participants do not disclose to one another the prices or amounts at which they are prepared to buy or sell and trades are completed in anonymity. Dark pools developed to respond to the special concerns of mutual funds and other large investors who worry about affecting a stock’s price when trading in large volumes. Like ECNs, dark pools allow participants to trade directly with one another and thus avoid paying a spread to a dealer or a commission to a broker.9

The average size of trades arranged in these pools is around 50,000 shares, and some trades can take place in even larger blocks. The dark pool world is highly populated. In late 2009, there were about 32 dark pool platforms, accounting for 8 percent of total trading in U.S. stocks. Among the larger independent dark pools are Liquidnet, Matchpoint, Pipeline, and POSIT, and many of the major broker-dealer firms have developed significant dark pool trading platforms.

Each dark pool has its own set of rules. We look here at just two, Liquidnet and POSIT, to illustrate how each dark pool operates differently:

- Liquidnet brings together fund managers by electronically linking its system to the in-house trade order management systems—often called trade blotters—used by fund trading desks. Assume, for example, that the Wentworth Fund, in its trade blotter, wants to buy 250,000 shares of Kellynch stock and the Uppercross Fund wants to sell the same amount. Liquidnet will scrape the blotters of the two funds—that is, it will detect that Wentworth’s and Uppercross’s orders can be matched and send an automated a message to each fund’s trading desk that a counterparty stands ready to trade Kellynch stock. The two trading desks can then anonymously communicate their respective bid and offer prices to each other and negotiate a price, all without having to tell the world at large that they’re buying or selling.

- POSIT, in contrast, handles the negotiation and trade automatically; POSIT does not scrape blotters like Liquidnet. Instead, traders place buy and sell orders with quantities only—no prices—into the system. At scheduled times during the day—at 10 A.M., for example—POSIT automatically matches buy and sell orders at a price midway between the current national best bid and the national best offer as reported in the consolidated quotation system. If buy orders outnumber sell orders, or vice versa, POSIT randomly selects orders to match.

Because the names of buyers and sellers are not disclosed, mutual funds and other larger investors can trade without tipping their hands as to their future intentions. So if the Avon Hill fund held 800,000 shares of a small cap stock, it could sell 20,000 on POSIT without generating fears that it was about to liquidate its entire position. On the negative side, trades entered into POSIT are not completed immediately, and the midpoint price might not be a favorable one when the trade is eventually executed.

ATS and the national market system. Where do alternative trading systems fit in to the national market system? While the ATS are included in the system, they are subject to a special SEC rule—known as Regulation ATS—that imposes a lower level of regulation if trading volume on the alternative platform remains low.

- Less than 5 percent of volume. An ATS is basically free from regulation as long as no more than 5 percent of the total trading volume in a stock takes place on its platform.

- More than 5 percent but less than 20 percent. Once an ATS crosses the 5 percent threshold, it becomes subject to the consolidated tape rule; it also becomes subject to the consolidated quotation rule, but only if it displays bids and offers on its system. (To avoid this rule, dark pools solicit only indications of interest with no price attached.)

- 20 percent or more. If trading in a stock reaches 20 percent or more of total volume, the ATS becomes subject to additional regulation, including a requirement that there be some access to the platform for all market participants.

The Convergence of the Old and the New

Both the NYSE and NASDAQ have transformed their own operations to respond to the competitive challenges posed by the ATS. NASDAQ acquired two major ECNs. The changes at the NYSE were even more dramatic: in 2007, it abandoned its monopoly specialist system and opened up trading to competing market makers. It acquired an ECN (renamed NYSE Arca) and now considers itself a hybrid market with a trading floor that operates alongside a fully electronic venue. And it merged with the company operating the Amsterdam, Brussels, and Paris exchanges and is now part of NYSE Euronext.

At the same time, some of the electronic venues are positioning themselves to compete head on with the traditional exchanges. The BATS ECN, for example, has registered with the SEC as an exchange, meaning that it is now fully subject to a wider set of rules. The upside is that BATS, as an exchange, gets a share of the fees paid by investors for access to the consolidated tape and consolidated quotes—a revenue stream not shared with ECNs. (While anyone can access the consolidated tape and consolidated quotes, there may be a fee for doing so.)

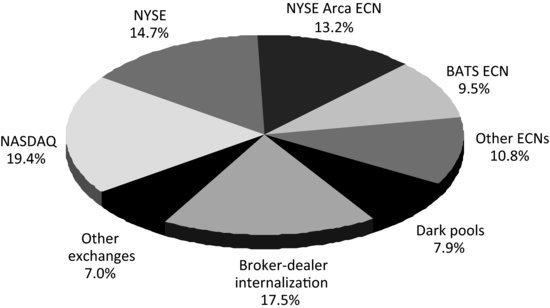

The intense competition among markets has led to a dispersion of trading among what are now called market centers, or trading centers, with no single one commanding a dominant position. In 2009, the three largest were NASDAQ, with 19.4 percent of total equity trading volume, the traditional NYSE with 14.7 percent and NYSE Arca, an exchange-registered ECN, with 13.2 percent. ECNs and dark pools combined, accounted for more than 40 percent of trading. Broker-dealer internalization—which occurs when a firm matches buy and sell orders from two different clients without using a trading center—accounted for 17.5 percent. (See Figure 8.1 for a breakdown.) Where a stock is listed no longer determines where it is traded; in 2009, only 20 percent of the volume of stocks listed on the NYSE traded on either the NYSE floor or on Arca.

FIGURE 8.1 U.S. Stock Trading by Market Venue (September 2009)

Source: SEC, Concept Release on Equity Market Structure, January 2010.

In earlier years, the SEC was worried that this sort of fragmentation of the markets would result in less liquidity and wider spreads. But high speed data linkages among the markets have had quite the opposite effect. For example, market depth has increased significantly, meaning that more shares can be bought or sold near the national best bid and offer than in the past. By late 2009, investors could, on average, buy 80,000 shares of stocks in the S&P 500 within 6 cents of the national best bid and offer. That compares to only 15,000 shares just six years earlier.10 Recognizing these developments, the SEC has abandoned the term fragmentation and now refers to the dispersion of trading among the market centers.

Trades are also being implemented at higher speeds (or, as it’s known in industry jargon, with lower latency)—though the flash crash on May 6, 2010, suggested that it’s not always a good thing. On that day, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 1,000 points in a matter of minutes. Regulators and academics will be parsing the causes of that crash for some time to come, but the preliminary reading is that the plunge was caused by computer-programmed stop-loss orders—which are market orders to sell—that kicked in as stock prices dropped. At the same time, traders willing to buy had fled the market because their computerized trading activities had been programmed to shut down automatically in response to the sharp market drop. All of this happened in such a short amount of time that humans couldn’t exercise judgment to intervene fast enough. Exchange-traded funds were particularly affected, as we discuss in Chapter 12.

To prevent a recurrence of a flash crash, in 2010 the SEC is testing new rules on a limited number of stocks and exchange-traded funds. The rules require that trading in an issue stop for five minutes if its price has fallen by 10 percent or more in the preceding five minutes. The trading halt acts as a circuit breaker that gives the system a chance to cool down when it is in danger of becoming overheated. These stock-by-stock circuit breakers are being added to a system of marketwide circuit breakers that impose a similar pause in trading when the market as a whole moves too far too fast.11 If the tests are successful, the SEC may apply the stock-by-stock circuit breakers more broadly.

The new market structure has also raised serious concerns about fairness. It has created what some consider unreasonable advantages for a select few, those that benefit from co-location and flash orders.

- Co-location. In co-location, a market center allows very active traders, often hedge funds, to place their computer servers in close physical proximity to the market center’s own computers, giving these traders a lower latency than other market participants. The speed advantage may be only a millisecond or two, but that can mean the difference between gains and losses. Critics of co-location are urging the SEC to adopt a rule that would prohibit this type of favoritism.

- Flash orders. Another issue of concern is the use of flash orders by hedge funds and other active traders. These are orders sent to a market center that are immediate-or-cancel orders. They take advantage of a loophole in the consolidated quote rule that allows certain immediate orders to be submitted without being displayed. The advantage that traders gain from flash orders? They are able to test the depth of the market for a stock, without having to follow all the rules that apply to other market participants. The SEC is considering revising the consolidated quote rule to require inclusion of flash orders as quotations.

More generally, the SEC is worried that an increasing lack of transparency in stock trading will make it easier for industry insiders to make profits at the expense of public investors. As we’ve seen, the alternative trading systems don’t have to provide information to either the consolidated tape or quotation system unless volume exceeds certain levels. Nor do broker-dealers have to provide quotations for trades that are executed internally. That means that more than 25 percent of trading activity is not completely captured in the national reporting systems. The SEC is particularly concerned about the impact of this undisclosed trading on individual investors, although one academic study concludes that the lack of transparency imposes higher costs on everyone, including the sophisticated investors using dark pools.12

To ensure that the markets remain fair for all, the SEC has proposed that the threshold that triggers reporting of trades to the consolidated tape be lowered from 5 percent of nationwide volume to 0.25 percent, and it’s evaluating whether indications of interest in dark pools should be treated as bids and offers that must be reported to the consolidated quotation system. It’s also considering limits on internalization of orders within a brokerage firm. Mutual fund managers are generally not in favor of these proposals, since they would reduce the ability to trade anonymously—to the detriment of the individuals investing in the funds.

THE ROLE OF THE MUTUAL FUND TRADER

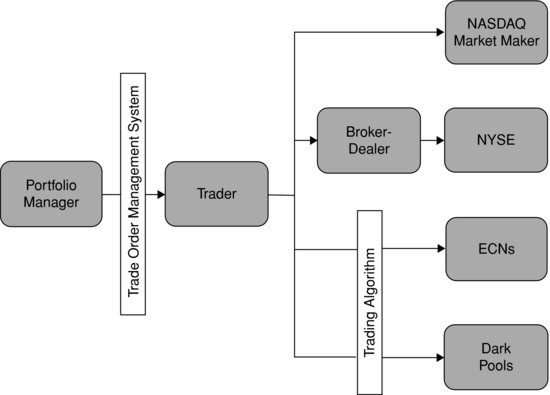

Executing a fund’s buy and sell orders on the best terms possible in this very dynamic environment is the challenge facing the mutual fund trader. Trading desks are usually organized around the type of funds that they serve, so a fund manager will normally have a bond desk, a money market desk, and an equity desk. Within each desk, traders are often assigned to particular portfolio managers and develop expertise in a specific type of security, whether municipal bonds or small company stocks. Figure 8.2 shows how traders act as a bridge between portfolio managers and market centers.

FIGURE 8.2 The Trader’s Role

We discuss in this section the responsibilities that traders have when executing buy and sell orders:

- Ensuring that the fund complies with all relevant rules

- Choosing a trading strategy that seeks to achieve best execution

- Selecting broker-dealers to execute trades

- Managing trading across multiple funds

After a trade is completed, the trading desk also works with investment operations to make sure that the settlement process goes smoothly. This is the back office aspect of a trade, when cash and securities actually change hands between buyer and seller. (Chapter 14 covers the process in detail.) We’ll concentrate on stock trading in our discussion. Fixed income traders have similar responsibilities, although they typically do not use brokers to execute trades for the funds. See the “Career Track” box for a glimpse at an equity trader’s typical day.

CAREER TRACK: MUTUAL FUND EQUITY TRADER

As an equity trader, a large part of your job involves communication— face to face, on the phone or by electronic means—with portfolio managers, broker-dealers, and the investment operations team. Let’s consider the handling of a typical trade, a buy of 40,000 shares of Highbury stock, which is currently trading at $47.

8:30 A.M. Before the market opens, the portfolio manager sends the trade to the desk electronically, through the order management system.

9:00 A.M. The manager calls the trading desk and gives you additional instructions: “There may be more behind it, so only do that size if you don’t have to push the price up too much.”

9:15 A.M. Since the stock is very liquid, you decide to try to execute most of the trade through a broker-dealer. You send an electronic message to the broker you’ve selected, then follow up with a phone call to your contact there. You give the broker a $46.75 limit order to buy 30,000 shares. You send through the trading desk’s electronic link to a dark pool an order to buy 10,000 shares at $46.80.

Morning. You monitor the progress of the order throughout the morning, talking with the broker periodically, but the broker has not found a counterparty prepared to sell at $46.75 or less. At noon, however, the dark pool has crossed buy and sell orders at $46.80 per share, resulting in the fund’s purchase of 10,000 shares.

1:00 P.M. In the afternoon, the broker calls to let you know that 50,000 shares are available at $47. Since part of your role is keeping the portfolio managers abreast of the latest market intelligence, you call her to relay this information. The portfolio manager wants to buy the 50,000 shares at $47 and sends you an order for another 20,000 shares electronically. You, in turn, convey the new instructions to the broker. You also enter another bid at $46.60 for 10,000 shares in the dark pool.

1:10 P.M. The broker calls to confirm that 50,000 shares have been filled at a slightly better price of $46.95 and follows up with an electronic message. You call the portfolio manager with the good news.

1:15 P.M. You ensure that the fill has been correctly entered in the trade order management system, so that the fund’s records will be properly updated.

2:00 P.M. The dark pool crosses buy and sell orders at $46.60, resulting in the fund’s purchase of the last 10,000 shares of the revised order.

As you can see, the trader’s job requires an attention to detail and good follow-up skills—in addition to an ability to read the markets.

Fund Compliance

Traders help to ensure that buy and sell orders comply with all the rules that are applicable to a particular fund, whether that’s a limitation established in the prospectus, a government regulation, or an internal policy. This can be straightforward, such as making sure that a fund doesn’t accidentally sell more stock than it owns. (Sounds simple, but when a fund complex holds thousands of positions, it can happen.) Special rules limit the amount of shares that a fund can purchase of any single company. Generally, a fund can acquire no more than 10 percent of a company’s voting stock. And many fund complexes put additional limits on the aggregate ownership of all their funds in a single company, such as 15 percent across all funds. Fund traders help monitor these and other restrictions, and it’s a critical role. If there’s an error that requires a fund to sell shares that should not have been bought, the fund management company may be required to compensate the fund for any losses.

To help traders with this task, most larger fund managers have computer systems that prescreen proposed trades to determine whether they are in compliance. In these systems, portfolio managers enter trades that are automatically checked before being routed to the trading desk. But even with these tools, fund traders must still remain vigilant, especially when handling trades that involve unusual or particularly complex circumstances.

Trading Strategy

Once the trader has confirmed that a proposed buy or sell is appropriate for a particular fund, it’s time to choose a trading strategy. The goal is simple: traders always seek the best execution possible for the fund—though there’s never a guarantee that they can achieve it. See “Doing Your Best” for a discussion of the difficulty of even defining the term. The decision is complex, since it involves both a selection of a venue and choice of approach for submitting an order within a market center.

Some of the more common trading strategies are:

Working orders. For NYSE-listed stocks, traders might decide to retain a broker who will work the order throughout the day on the exchange floor, on ECNs or through market makers not based on the exchange floor and therefore often called upstairs market makers. The trader might keep part of the order to work directly, sending bids and offers to one or more ECNs or dark pools. Other times, the trader might not give the broker the entire order at once, but instead place only part of the order at first, perhaps with a limit (“Take 25,000 Northanger to buy with a $46.50 top”). If the trade is going well, the trader can increase the order until the entire amount is placed. If not, the trader has not revealed the entire order and can later either place it with another broker or take back control of the order, executing it using the trading desk’s direct links to ECNs, dark pools, and other electronic trading centers. This multipronged approach is normally used for large or mid-size orders.

Basket trades. Another strategy is the basket trade, also known as a program trade, portfolio trade, or list trade. It’s often used when a trader has a long list of orders; that may happen when a fund needs to buy or sell a slice of its entire portfolio to either invest or raise cash. The trader will show the entire list to a small group of broker-dealers who compete for the business. Sometimes the list does not name the stocks but simply gives other details, such as market caps and price volatility of the stocks in the basket. If a fund is the selling stocks in a basket trade, the firm that offers the best combination of price and fees buys the full set of stocks at a specified price from the fund. Because the risk of the entire group of stocks taken as a whole is typically less than the risk of any single stock, funds can normally get a better execution when they trade stocks as baskets rather than one by one.

DOING YOUR BEST

While best execution is simple in concept, it’s been tough to define in practice. The normally precise SEC, for example, has not spelled out exactly what it means when it now refers to the term.

Seeking best execution entails balancing a number of factors. It’s assessed over time and over many transactions, rather than trade by trade. Best execution is not just getting the best price and incurring the lowest trading commissions and fees, although those are both extremely important. It also considers the risk of not executing a trade if price and cost are the only considerations. The ability to remain anonymous often factors into an assessment of best execution, since the fund might get a worse price or maybe even not be able to complete an order at all if its intentions become public.

If defining best execution is difficult, measuring it is even harder. One common approach is to compare the trade price to the average price for other similar trades made that same day using a measure called the volume-weighted average price, or VWAP. Another technique, called implementation shortfall, is to estimate the expected cost of a trade based on the trading pattern of a stock, and then see how actual results stack up against the estimates. (Estimated costs will be higher for more volatile or less liquid stocks.) Specialized consulting firms collect and store market data and provide fund trading desks with extensive reports analyzing their trade results using one of these two approaches.

Electronic trades. Working the order directly in electronic markets is the most common strategy for orders in NASDAQ stocks. That’s a change from the recent past, when traders almost always went to the market maker displaying the best quotes. While that’s still done today, it’s no longer the dominant practice. Electronic markets also offer an efficient way for the desk to trade small orders.

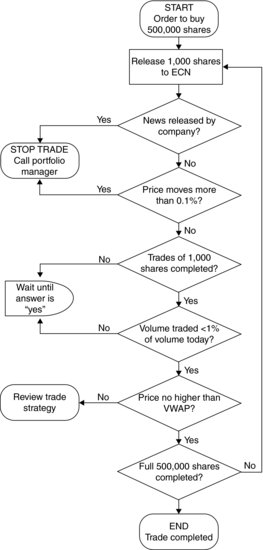

Algorithmic trading. For very large orders, on the other hand, traders today often opt for algorithmic, or algo, trading, using mathematical models or algorithms that are programmed into the trading desk’s computer systems. These models automatically submit a series of trading orders to an electronic network; the exact sequence depends on price movements in the stock or other factors. (Figure 8.3 gives a very simple example.) Algo trading allows the desk to easily break large orders into multiple, smaller orders, enabling the fund to maintain anonymity and reduce market impact.

FIGURE 8.3 A Simplified Trading Algorithm

Trading desks work closely with quantitative analysts to develop effective algorithms, and they track results to determine which work best in particular circumstances. They are constantly fine-tuning their approach, trying to gain even more of an edge.

Algo trading is a fairly new phenomenon linked to the rise of the alternative trading systems, but it has already had a profound effect on the markets. Because it breaks up large orders into small ones, algo trading has caused a dramatic decrease in average trade size.

Broker-Dealer Selection

A decision to work an order with a broker-dealer creates another decision point: which broker-dealer to choose? Again, seeking best execution takes precedence. The trader may choose a firm that has expertise in a particular sector or that has been active in the stock recently or that has demonstrated its ability to handle similar orders well in the past. Beyond best execution, traders may consider research services and must pay particular attention to the use of affiliated brokerage firms.

Soft dollar services. When selecting a broker, traders are permitted by law to consider not just how well the broker executes trades but also the research services that a broker supplies to help the portfolio managers make successful investment decisions. This research often consists of investment recommendations from the brokerage firm’s own team, familiarly known as Street research. At other times, the research may come from third parties at the broker’s expense. This third-party research may take the form of electronic data feeds and quotation services, such as Reuters or Bloomberg, rather than traditional investment analysis. That’s possible because the SEC defines research quite broadly. Many of these services are essential to the operations of fund managers.

Many brokers do not charge for any of these research services in hard cash dollars. They may instead expect to receive a certain level of trading volume from a fund. In many fund complexes, the portfolio managers give input to the trading desk on which brokerage firms have supplied the most valuable research, and the traders keep this information in mind as they direct orders. The commissions paid for these trading services may be higher than those charged by an execution-only broker that does not supply any research. In industry parlance, payments for trade execution and for research are bundled together in the commission. More lingo: the portion of the commission that compensates for a broker for providing investment research is called soft dollars.13

Soft dollar research has attracted considerable criticism in the past. Detractors argue that it’s inappropriate for investors to subsidize, through commission payments, a fund manager’s research process, which they contend should be included as one of the basic services provided in exchange for the management fee. They note that the system encourages portfolio managers to do more trading so that they can generate more in commissions. Defenders of soft dollars point out that Congress has specifically sanctioned the practice. They also argue that banning soft dollars would be likely to reduce competition in the fund industry, since smaller managers depend more on soft dollars than larger ones.

The practice is less controversial today. That’s partly because of the increase in electronic trading; the commission rates on these trades are very low and include execution services only, making the soft dollar pool much smaller. And SEC guidance on what can be paid for with soft dollars and how to design commission agreements has ended some of the most-criticized practices. “Independent Monitors” discusses the role of the board of directors in monitoring soft dollars and other trading issues.

INDEPENDENT MONITORS

As you can see, in some trading situations, the interests of the fund and of the fund’s managers can diverge. To make sure that funds are treated fairly, the SEC has given the independent directors on fund boards special responsibility for monitoring both trading policy and trade execution. Fund boards of directors must review all trades that take place between funds advised by the same manager or that involve an affiliated broker-dealer. Independent directors will also look at the manager’s soft dollar and trade allocation policies and practices. Nor do they neglect the big picture: they’ll review the overall quality of trading, often using reports from one of the firms that evaluate best execution.

Use of an affiliated brokerage firm. Traders working for larger financial services companies may need to consider one other factor in their choice of a brokerage firm. If their company also owns a broker-dealer, they must limit the fund’s trading with that firm. Under the provisions of the 1940 Act, the affiliate may only act as an agent for the fund, helping it to arrange trades with other, unaffiliated buyers and sellers; it may not buy or sell securities directly from the fund. Because of the conflict of interest, some funds prohibit affiliates of the fund manager from acting as a broker or severely limit the use of their services. The SEC has also placed restrictions on the purchase of securities in a public offering if the affiliate is part of the group underwriting the offering.

Trading Across Multiple Funds

A mutual fund manager can easily oversee a number of funds, and they all come to the trading desk to buy and sell. Traders are responsible for ensuring that each fund is treated fairly. They get involved with multi-fund issues in three ways: fund cloning, trade allocation, and interfund trades.

Fund cloning. In many fund complexes, one portfolio manager may be in charge of multiple versions of the same portfolio. For example, he may manage a mutual fund sold to U.S. investors only, a mutual fund sold to non-U.S. investors, and an account for single large client—all using the same investment approach. To manage these different customers fairly and efficiently, the portfolios may be cloned, meaning that their holdings are as closely aligned as is practicable in terms of percentage weightings.

At some money managers, the trading desk is responsible for implementing the cloning. The portfolio manager often personally manages the largest of her funds; the traders then replicate any changes in that fund in the smaller accounts. This is not always as easy as it may sound, since the smaller accounts may have special constraints imposed by the particular client, or it may not be feasible to obtain exactly the same securities at the same price for all accounts. The traders must then make adjustments as appropriate.

Trade allocation. When trading for multiple funds, trading desks usually bunch orders for the same stock, executing them all at the same time. That approach ensures that all of the funds are treated exactly alike, eliminating any accusations of favoritism. It works particularly well when the desk is able to complete the trade on the same day.

But what happens if only part of the trade has been completed by the close of business? How are the shares allocated among the funds that participated in the order? Generally, traders will allocate the stock on a pro rata basis, filling the same percentage of the initial order for each fund. But if one portfolio manager had provided slightly different instructions, the desk might need to make a judgment call on how that affected the ultimate execution and adjust the allocation accordingly. Very small funds might get precedence in the allocation, since, if not for their larger cousins, they’d have easily completed their orders. And very small trade executions, not uncommon when purchasing hot initial public offerings, may be rotated among funds on a predetermined schedule.

Interfund trades. Traders must also manage situations in which one fund is buying and another is selling. This may happen because funds have different cash flows or because two portfolio managers have opposing views on the outlook for a particular investment. The trader must determine whether to cross the trade between the two funds, without placing an order in the market. This saves both funds the execution costs, but the trader must be certain that the proposed transaction is in the best interests of both funds. The price on an interfund trade is determined by SEC regulation; it’s usually the last sale price for stocks and the average of the bid and the ask for other securities. All of these trades must be reviewed by the board of directors.

TRADING IN BOND FUNDS

While we have focused on transactions in stock funds, trading is arguably even more important in bond funds. Because returns on bonds are generally lower than stock returns, costs play a bigger role in determining fund rankings—and that includes the costs related to trading.

The sheer number of bond issues creates tremendous challenges. Because there are more bonds issued in a year than there are stocks trading, just tracking down the other side of a trade in a particular issue can be quite difficult. For example, bond fund managers might not be able to find a seller of a bond that they’re interested in buying. They might be offered a similar issue instead, and they’ll have to decide whether the substitution is consistent with their portfolio strategy. In other words, the line between trader and portfolio manager is much fuzzier in bond funds—sometimes the roles are even combined, especially in smaller firms.

The wide variety of types of bonds means that a trader must be familiar with many different submarkets. For example:

- U.S. Treasuries are extremely liquid and trade with very narrow spreads, so buying and selling them is only a challenge when extremely large blocks of securities—valued at billions of dollars—are involved.

- High-yield bonds are less liquid, and trading them can be quite complex. Their prices may be influenced by the issuer’s earnings outlook and perhaps by moves in its stock price, and spreads will vary widely, depending on the size of the issue and its credit quality. A smaller, lower-quality high-yield bond issue might trade by appointment only, to use a favorite trading desk phrase, while a larger one rated BB might be readily available.

- Traders working with structured securities need to be familiar with the complex characteristics of those issues, to understand how they’ll be affected by market factors, including economic news.

There’s no one place to turn to trade all these different types of bonds. There aren’t any bond exchanges like NASDAQ and the NYSE, which—despite their decreased market share—still have a significant place in stock trading. Instead, bond trading is widely dispersed.

Bonds can be bought and sold in one of two ways:

1. New issues. Bonds can be bought in the primary market when they are issued by a corporation or government. There is a steady flow of new issues, if only to replace the bonds that mature every year. The new issue market is particularly important in the municipal market. Traders must keep on top of the calendar of new offerings and make sure that the portfolio managers are aware of the timing of deals.

Even in the new issue market, different types of bonds are handled differently. U.S. Treasuries can be bought directly from the government through a program called Treasury Direct or indirectly through a primary dealer. Other types of bonds will generally be marketed through broker-dealers.

2. Dealer market. After they are issued, bonds can then be bought and sold in the secondary market. The bond market is an over-the-counter or dealer market, which means that investors transact with a broker-dealer who is either acting as principal or agent. If the investor is selling and the broker-dealer is acting as a principal, the broker will buy the bond for its inventory. When the broker-dealer already has a client on the other side of the trade, it will act as agent and simply trade the bonds from one party to the other—taking a small spread out of the price as compensation for its services.

In recent years, technology has started to bring more coordination to the bond market. For a long time, bond traders could get good pricing information only on government securities. Now, there are two separate systems providing consolidated trade price reporting. For corporate bond trades, the system is called TRACE, which stands for Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine, and it’s run by FINRA. The equivalent in the municipal bond world is the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board’s Real Time Transaction Reporting or RTRS system. But unlike stock trades, which are automatically reported almost instantaneously, there is a lag time in the reporting of bond trades: dealers need only report trades within 15 minutes of execution. All of the trade information—and much more—is available on Bloomberg. (And, yes, it’s related to the New York City mayor, who founded the company.) Virtually all professional bond traders have the Bloomberg information system on their desktop and use it constantly to access data about bonds.

Trade execution has also gone electronic in the bond world. TradeWeb is the largest electronic trading platform, and there are others, including BondDesk and MTS BondVision, that have developed a lead in specific niches. But there is a key difference between these systems and the ECNs in the stock arena: all of the bond platforms serve to connect investors to dealers. Direct trading between investors—each on an ECN or through a dark pool—is still only a minor component of bond trading.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Trading can have a significant impact on fund performance. Because a fund buys and sells in large size, it can have a market impact, driving up the price of securities it’s trying to buy and pushing down the price of securities it’s trying to sell. Other investors may try to anticipate a fund’s actions and try to earn a profit by front running them. Many mutual fund management companies have dedicated traders—working on trading desks—who focus on minimizing the cost of buying and selling investments.

Trading in U.S. stocks today is largely electronic and is widely dispersed among many market centers. The traditional stock exchanges—the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ—continue to play an important role in stock trading, although their market share has fallen dramatically in the past decade. In contrast, alternative trading systems have gained share. There are two types of alternative trading systems: electronic communication networks and dark pools, each operating with its own set of rules. Despite the diversity of their features, all of these systems allow investors to trade anonymously with each other without the involvement of a broker-dealer.

Mutual funds and other large investors have supported the development of alternative trading systems because they believe that trading through them creates less market impact. However, some industry observers are concerned that individual investors are worse off under the new system. That’s because the alternative trading systems are not always required to publicly report trade information. Also, the new systems have not yet been fully tested in extreme market circumstances, as demonstrated by the flash crash of May 2010. Preliminary analysis suggested that automation played a key role in the market plunge.

The mutual fund trader is charged with seeking the best execution possible by selecting the trading venue and approach that will enable the fund to implement its investment decisions at the lowest possible cost, considering both opportunity cost (meaning the cost of not trading) as well as direct costs such as spreads and commissions. As part of this process, the trader may select brokerage firms that provide important investment research in addition to trade execution services. The trading desk also plays a key role in helping a fund comply with all the relevant rules, including regulations on trading with affiliated firms, trade allocation, and interfund trading. All of these activities of the trading desk are overseen by the independent directors of the funds.

Because of the large number of bond issues, fixed income trading is arguably even more complex than equity trading. There are no central exchanges for bonds, with the result that trading is highly dispersed. Investors can buy bonds from the issuer in the primary market or through a dealer in the secondary market, often through an electronic network. Unlike stock investors, however, bond investors rarely trade with each other.