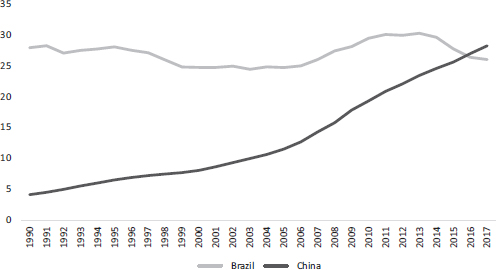

Figure 11.1 GDP per capita as a percentage of the U.S.: Brazil and China, PPP, 1990–2017

This chapter seeks to understand the possible drivers of future income and employment growth. Its key finding: Brazil needs to dramatically improve its performance across all industries in terms of firm-level innovation if the country is to generate lasting gains in incomes and provide better jobs for its citizens. This is even more important because Brazil is aging rapidly, and the boost the country has enjoyed thanks to its young and growing labor force is disappearing.

Productivity growth is a measure of whether a firm, industry, or country is using its assets more efficiently over time to produce more output with the potential to generate more jobs and more affordable products – both by resources being shifted to more efficient firms and by innovation, and, more importantly, including the adoption and use of existing technologies by firms. Brazil has abundant natural resources, an increasingly educated labor force, and some world-class companies in industries ranging from agribusiness and aeronautics to oil drilling. However, in aggregate the country uses its assets poorly. As documented in this chapter, if Brazil were to use its existing assets as productively as the United States, Brazil’s income per capita would increase almost threefold. This is not, as is often argued, because Brazil specializes in the wrong activities and should be promoting more production in a few specific industries. Rather, the country is inefficient in most of the activities it undertakes, with most firms far from the global technological frontier. Shifting Brazil’s production structure to be the same as that of the United States would raise productivity by just 68%; making all Brazilian industries work as efficiently as their counterparts in the United States would boost productivity by more than 400%.

The chapter analyzes some of the factors that may be behind Brazil’s low innovation. Among the most important are: (1) insufficient external and internal market competition due to a business environment that favors incumbents and prevents firms from having access to existing technologies at globally competitive prices; (2) government policies that have protected and subsidized less-efficient firms rather than foster competition and innovation; and (3) fragmented government institutions for business support that have allowed ineffective policies to persist. Many entrepreneurs have accordingly allocated their talent to unproductive activities, namely seeking continuation of these state privileges, rather than to productive activities such as investing in innovation. This chapter recommends a policy shift with the objective to change the relationship between business and the state from one governed by perks and privileges to one built on creating a level playing field that incentivizes all entrepreneurs to invest in innovation.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows. Section 2 highlights why productivity growth driven by innovation is needed and urgent. Section 3 discusses policy barriers to innovation. It focuses on barriers to market integration and business-support policies that shield incumbent firms from competition and thereby enhance the profitability of investing in securing continued state privileges over investing in innovation. Section 4 explores barriers to investment in agricultural innovation. Section 5 assesses these policies from the perspective of shared prosperity. Section 6 concludes with a discussion of the importance of strengthening government capabilities to better design and implement innovation policies.

The average Brazilian today is no better off than a generation ago relative to the United States: Brazilian per-capita income in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms remains about 25% of U.S. levels. In contrast, the average Chinese has caught up and surpassed Brazil in per-capita income terms over this period (see Figure 11.1).

The lack of convergence in living standards is associated with a poor record in productivity growth. Productivity growth is a critical driver of development in all countries. Yet Brazil has not been good at it, with labor productivity since the mid-1990s increasing only around 0.7% per year and total factor productivity (TFP) growth declining by 1% over the 1996–2015 period. It is true that since the early 2000s, Brazil has experienced a significant increase in per-capita incomes and a remarkable reduction in poverty. However, the drivers of these improvements are unlikely to be sustained. Most importantly, Brazil’s income growth has relied predominantly on an increase in employment, as many young people have entered the labor force for the first time. With the population aging rapidly, this source of growth will soon be exhausted.

Boosting TFP growth to 2.5% per year – a rate achieved in Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s – would raise Brazil’s growth potential permanently to 4.4% even without an increase in investment.2 Of course, the gains to Brazil’s potential growth would be even higher if national savings and investment rates could also be raised alongside productivity growth.

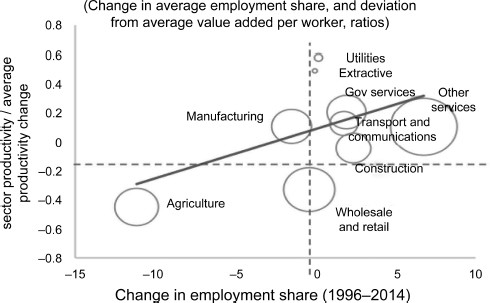

While structural change has contributed to increasing productivity in the past, Brazil’s structural composition is not the main source of its productivity gap. Productivity growth can be driven by structural change, namely a reallocation of resources from less to more efficient industries, and by innovation including technology adoption. Is Brazil’s low productivity growth explained mainly by structural change? Would shifting more resources to a few specific manufacturing industries be the solution? Figure 11.2 shows changes in employment shares and the relative productivity of groups of industries, measured as the log of the ratio between sectoral productivity and average productivity between 1996 and 2014. For positive gains to occur through structural change, sectors would either be in the top right quadrant (e.g., other services, where labor has shifted into relatively high-productivity sectors) or in the bottom left quadrant (e.g., agriculture, where labor has shifted out of low-productivity sectors). The graph shows that structural change did play a positive role in Brazil, but that this was limited mainly to a shift between agriculture and other services. In spite of subsidies to manufacturing, the sector is on the left side of the graph since it lost workers over this period. A recent study across 35 economic sectors shows that if Brazil had the same sectoral labor allocation as the United States, aggregate productivity would increase 68%. But if Brazil had the same sectoral productivities as the United States, aggregate productivity would increase 430% (Veloso et al., 2017). Hence, low Brazilian productivity relative to the United States is mainly due to low productivity “within” most activities.

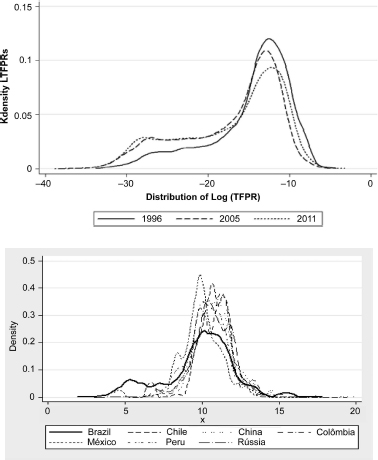

Low productivity is not explained by what Brazil produces but by how its firms produce. Low productivity is a systemic economy-wide problem, with insufficient innovation in all activities. In a well-functioning economy, the process of competition results in more resources being allocated to more innovative firms, allowing them to adopt better technologies, expand output, and generate more jobs – with less productive firms either learning from their competitors or downsizing and exiting. This process leads to TFP distributions within industries that are relatively narrow and concentrated around a high and growing average level. However, in Brazil, the dispersion of real TFP across firms within the same industry averaged across manufacturing is high and asymmetric with a fat lower tail (Vasconcelos, 2017). High dispersion implies that all less-efficient firms could produce more output with the same amount of inputs if they adopted better technologies. Furthermore, the distribution in Brazil became more dispersed through time, with more firms concentrated into the low tail of the TFP distribution in 2011 than in 1996 (left-hand side of Figure 11.3). And compared to international peers across both manufacturing and services industries, the fat tail of low-productivity firms is larger and the average productivity is lower in Brazil (right-hand side of Figure 11.3). In fact, the dispersion of productivity presented in Brazil is the largest among the countries analyzed. Disaggregating the data at the sectoral level shows that the problem affects most sectors of the economy, albeit to different extents (Barbosa Filho and Correa, 2017). Potential productivity gains from within-industry reallocation of resources to the most efficient producer are in the order of 40% in manufacturing and more than 250% in retail (De Vries, 2014). Brazil could achieve dramatic gains in productivity at the sectoral and firm level by using its existing assets and resources more efficiently – allowing workers to shift and be employed by the more innovative expanding firms.

Figure 11.2 Labor shifts from agriculture to higher return services contributed to productivity

Source: IBGE, WDI, Groningen, World Bank staff calculations.

Note: Size of the circles refers to size of sectoral employment share in the economy.

Source: Vasconcelos (2017); Barbosa Filho and Correa (2017).

Many existing policies impede rather than support the allocation of entrepreneurial talent and investments in innovation. These policies shield incumbent firms from competition and thereby enhance the profitability of investing in securing continued state privileges over investing in innovation. They include international and domestic trade barriers impeding integration into domestic and global value chains, and business-support policies that protect incumbent firms from competition.

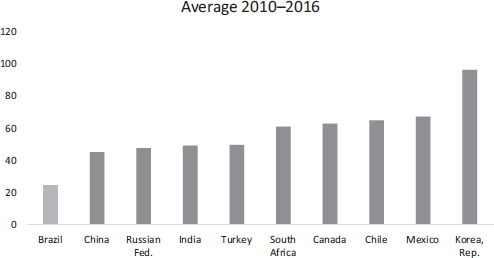

Openness to trade in Brazil is limited, reflecting a highly interventionist and protective policy stance. Brazil has one of the lowest indicators of trade openness in the world, with exports plus imports as a share of GDP at 24.7% over the 2010–16 period relative to the worldwide average of 51.3% (Figure 11.4). Protective trade policies including high tariff and nontariff barriers to imports contribute to this lack of global integration. Brazil’s average (trade-weighted) effective tariff rate was 8.3% in 2015, the highest rate in comparison to other emerging and advanced economies (Figure 11.5).3 Beyond tariffs, NTMs (nontariff measures) and procedural obstacles to trade are widespread, raising the costs of trade. The coverage ratio, or percentage of imports subject to at least one NTM, is higher in Brazil than in other countries: 89% for technical barriers, 66% for sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and 65% for quantity controls – well above the world average. Between 2008 and 2014, Brazil was second only to Indonesia in the number of LCRs (local-content requirements) used, with 17 LCRs in force.4

Figure 11.4 Brazil has a lower trade share than peers (2010–16 average)

Source: Estimations using UNCTAD TRAINS and UN COMPTRADE data.

Figure 11.5 Brazil has higher trade costs than peers (2015 average effective tariffs)

Source: Estimations using UNCTAD TRAINS and UN COMPTRADE data.

At the firm level, integration into global value chains (GVCs) offers particularly important potential innovation benefits. GVC participation can bring positive effects on productivity and innovation through three main channels: specialization in tasks, access to a larger variety and quality of intermediate inputs, and knowledge spillovers from multinational enterprises. Stronger integration in GVCs (as both buyers and sellers) is associated with higher productivity levels of Brazilian firms. Indeed, the differences among Brazilian firms are much larger than in other countries, probably because integration overall has been so limited.5

High costs of information and communication technologies (ICT) affect connectivity and may reduce the rate at which new technologies are adopted. As of September 2017, Brazil was the most expensive of 57 surveyed countries for buying an iPad: it cost more than twice as much as in California and Hong Kong.6 Brazil is one of the five countries (out of 125) with the highest cost of adopting digital technologies (Figure 11.6), with tariffs adding 16% and special taxes adding an additional 5% to the cost of a basket of ICT goods and services. The estimated increase in annual ICT adoption by firms due to the removal of these tariffs and special taxes in Brazil is significant, with increases in end-user consumer demand ranging between 17% and 37%. Removing these ICT tariffs and taxes could increase GDP per capita by 1.5% per year (Miller and Atkinson, 2014). In addition to increasing average incomes, technology adoption has the potential to boost productivity growth, employment creation, and wages. Higher employment and wages are found for both higher- and lower-skilled workers as a result of investment in ICT capital by manufacturing firms in Argentina (Brambilla and Tortarolo, 2018), increased high-speed Internet use in Colombian manufacturing firms (Ospino, 2018), and a greater share of labor using the Internet in Mexican manufacturing firms (Iacovone and Pereira-López, 2018).

A key reason for persistent resource misallocation and limited competition arguably is the high regulatory and administrative barriers against doing business in Brazil. Brazil’s cost of doing business is high and persistent enough to have earned it a special name – Custo Brasil. What is often less appreciated is that while incumbents have learned to live with high costs of doing business, Custo Brasil is a more onerous impediment to new entrants and young, growing firms. Since it is more difficult for innovators and disruptors to grow, competition may be dampened and incentives for incumbents to change may be correspondingly reduced (Klapper et al., 2006).7 Key components of Custo Brasil in addition to the inadequate state of the country’s physical infrastructure include regulatory obstacles such as entry barriers (Fuentes and Mies, 2017); high tax rates and an extraordinarily complex tax system; high interest rates and a weak insolvency regime; and cumbersome processes to operate a business, including time and cost to register property, obtain construction and environmental permits, and bid under government contracts – together with variations in many of these regulatory requirements across municipalities and states.8

Business-support policies further distort resource allocation and dampen incentives for innovation. Subsidies, directed credits, tax exemptions, local-content requirements, government procurement preferences, and other business-support policies are often justified to compensate for Custo Brasil, in addition to promoting other objectives such as regional development and the support of “national champions.” However, there is little evidence that they have had much impact (IADB, 2017). Instead, they have created substantial rents that have sheltered inefficient companies, made it more difficult for new investors to enter the market, and thus allowed substandard business practices to persist.9 Moreover, despite limited benefits, the cost of business-support policies has been very high. Federal spending on business-support policies more than doubled in real terms in the past decade, jumping from R$125 billion in 2006 to R$267 billion in 2015, or around 4.5% of GDP – with tax exemptions being the main driver behind this overall expenditure rise, followed by subsidized credit and general spending (Figure 11.7).

Tax exemptions (TEs) have achieved little impact at high fiscal cost. TEs are by far the most important component of federal spending on business-support policies in Brazil, accounting for almost 61% of total spending and 2.9% of GDP in 2015. TEs have doubled in real terms over the past decade, from R$79.6 billion to R$162.8 billion between 2006 and 2015, a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.3%. Incentive programs purportedly aimed at promoting innovation include the following?

Figure 11.7 Total federal fiscal spending on business-support policies grew to 4.5% of GDP

Source: Dutz, Barroso, et al. (2017).

The fiscal incentives created by the Lei de Informática (Informatics Law), instituted in 1991 and renewed most recently in 2014, promote increased local content of ICT hardware and related electronics assembly plus investments in local R&D operations. The program was intended to assure ICT hardware and related electronics firms outside the Zona Franca de Manaus (ZFM) that they would not remain at a competitive disadvantage for not relocating there. Similarly, the Lei do Bem (Fiscal Incentives Law), instituted in 2007, sped up and expanded incentives for investments in R&D, authorizing companies that invest in R&D and meet certain requirements to claim tax incentives automatically for certain types of spending.

The incentives for R&D and innovation provided by the Lei de Informática have not been effective. Kannebley and Porto (2012), using firm-level data from 2000 to 2010 on 65,000 firms, show that the law has been ineffective in stimulating productivity-enhancing R&D, as beneficiaries have not been able to produce internationally competitive ICT products. Although the policy has incentivized all ten leading global ICT hardware firms to produce locally, Brazil continues to rely on imports of intermediate goods, registering a negative trade balance over 2010–14 in all eight identified ICT hardware-related subsectors, with a worsening of the trade balance in seven of these subsectors over this period. Moreover, Brazil’s exports of final ICT goods have also been falling over these past five years at a CAGR of −16% (Zylberberg, 2016). Regarding the Lei do Bem, while the program has had a positive impact, its performance in boosting R&D intensity is significantly below what would have been expected for such a program (Devereux and Guceri, 2015). More broadly, based on cross-country evidence, Bravo-Biosca, Criscuolo, and Menon (2013) show that TE support for R&D has a positive impact on employment growth only in incumbent firms with relatively low growth rates, while it has a negative effect on firm entry and on the employment of firms at the top of the growth distribution. This suggests that R&D TE incentives are likely to favor incumbent firms and slow down the reallocation process.

The program has a significant TE component. Launched in October 2012 for the period 2013–17, its stated objective was to protect the local auto industry against imports and to support technology upgrading. The program raised the IPI (Tax on Industrialized Products) by 30% for all passenger cars and light commercial vehicles, thereby also raising the import cost for finished vehicles to penetrate the Brazilian market. The program then enables vehicle producers, assemblers, and distributors to offset this tax increase by up to 30 percentage points if they meet several requirements for local production or sourcing, minimum spending on R&D, or engineering and vehicle labeling for energy efficiency. While the program has been effective in limiting imports, it seems to have failed to make the Brazilian car industry competitive, as it appears to have had no impact on production and employment levels, and little on innovation (Sturgeon et al., 2017). A simple comparison with the agricultural machinery industry, which does not enjoy the same type of protection, shows that the expansion of the two industries has been very similar, such that the program did not alter industry competitiveness enough to have a positive effect on output and jobs in the automobile sector. It resulted in smaller-scale production and higher consumer prices. Most of the protection is in the form of trade barriers. As such, most of the cost is borne by consumers through higher domestic sales prices. The program has been found to be noncompliant with WTO rules.

A comparison of management quality technologies across countries also suggests insufficient competition and technology adoption. A large literature has recently developed on management quality. One output of this research is the development of a management quality index at the firm level, which can be aggregated to compare countries. A causal link has been established between the adoption of better management practices and firm-level productivity growth, increased employment, and increased wages (Bloom et al., 2013). Management quality differences can explain up to 35% of the income gap between countries; estimates suggest that around a quarter to a third of cross-country and within-country TFP gaps appear to be management-related (Bloom, Sadun, & Van Reenen, 2016). Across countries, Brazil not only lags Mexico, Poland, Chile, Turkey, and Argentina on average, but its tail of poorly run firms is fatter than for Mexico, China, and the United States: almost one-fifth of Brazilian firms were classified as poorly managed, nine times more than in the United States (Figure 11.8; Bloom et al., 2014; Maloney and Sarrias, 2017). And even for the best Brazilian performers, management practices would need to improve to reach the level of global leaders. Product market competition could encourage firms across the management quality spectrum to work harder, both thinning the badly managed (trimming the left tail) and incentivizing survivors (moving the whole distribution to the right).

Source: Prepared by Daniela Scur using World Management Survey data, www.worldmanagementsurvey.org.

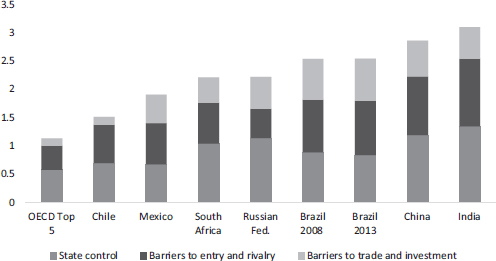

Source: Product Market Regulation WBG OECD database.

Note: OECD top five are Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the U.K.

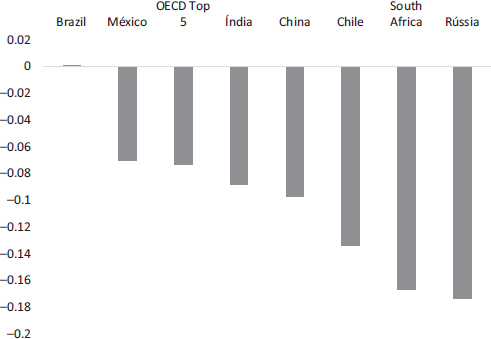

Figure 11.10 Brazil is the only country with no reduction in restrictiveness to competition

Source: Product Market Regulation WBG OECD database.

Note: OECD top five are Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the U.K.

The impact of greater product market competition on productivity and innovation is quantitatively large. A 10% decrease in the average manufacturing price-cost margin in Brazil, as would likely occur with greater competition, is associated with an increase in labor productivity growth of more than 3% per year. These results matter even more because Brazil seems to suffer from significantly higher barriers to competition than comparator countries (Figure 11.9). Restrictions to international trade are particularly notable, as is the fact that Brazil is the only country among comparators where the overall restrictiveness of policies and regulations did not improve between 2008 and 2013 (Figure 11.10).

Agriculture stands out as the only sector with consistently high rates of productivity growth in Brazil. Indeed, unlike in manufacturing and (to a lesser extent) services, where Brazil lags the rest of middle- and high-income countries, in agriculture Brazil is a leading innovator with high rates of productivity growth. Prior to the 1970s, Brazil produced a negligible quantity of soybeans; today, it exports 80 times more than 40 years ago, and is the world’s largest exporter (with the United States remaining the largest producer).

Brazil’s impressive agricultural productivity growth over the past decades has been made possible by both increased input use and the adoption of new technologies. Brazil has been the top country, jointly with China, in average annual agricultural TFP growth over the past five and a half decades, including both crops and livestock. And over the most recent decade (2005–14), it has continued to benefit from higher TFP growth than most comparator countries except China, France, and India (Figure 11.11). TFP growth was made possible through innovations facilitating more productive use both of existing cultivated land as well as of significant amounts of previously underutilized water and land resources, such as huge areas of previously less productive tropical and semi-arid lands in the Cerrado.

Agricultural productivity growth over the past decades highlights the innovation benefits of (1) being globally open, subject to world prices; and (2) having relatively effective public policies – even though their cost efficiency and mix could be improved to promote further productivity growth and competitiveness. More efficient agricultural production and expansion were supported by public policies focusing on agriculture innovation (agriculture research, extension, and education). Combined with private research and development, these policies helped especially the most efficient larger producers to find ways to increase yields of crops and cattle ranching by adapting production technologies to the specific ecological and topographic conditions of Brazil’s various biomes. Agricultural expansion also was supported by an increase in the volume of rural credit (including both subsidized credit and commercial and family producers’ debt rescheduling), especially after the macroeconomic stabilization of the mid-1990s. Importantly, favorable export policies and the reduction of import tariffs on food in the early 1990s maintained a competitive playing field and enabled the boost in productivity. This is a key difference to the industrial sector and may explain why subsidized credit and other policy interventions were associated with increases in productivity.

Despite past success, Brazil’s agricultural support policies may be running into their limits and could be much more effectively targeted. The net level of support provided by Brazil’s agriculture public policies and programs has historically been low and even negative until 2000 due to taxation (see Figure 11.12). Current support to the sector amounts to just 3.8% of gross farm receipts, which is equal to only 0.55% of total GDP (compared to an average of 1% in OECD countries). However, these policies are distortionary, relying heavily on directed (earmarked) and subsidized agriculture credit as the main tool to operationalize them, as well as subsidized farm prices administered through direct government purchases and various subsidized agricultural insurance programs. These support policies distort credit markets overall and farmers’ production decisions, as many of these programs are targeted to specific crops, livestock products, and inputs, and often vary by region. Moreover, the bulk of subsidized rural credit benefits Brazil’s largest farmers, who have access to market financing and hardly require additional support. If these policies and programs were reformed to focus state support on small and medium-size firms and allow the development of complementary market-based support solutions for large commercial agriculture where feasible, the sector could see a further boost in productivity and competitiveness.

Brazil can rely on its homegrown agricultural innovation capacity to make the necessary transition while closing the domestic productivity gap. Brazil’s federal agricultural research institute, Embrapa, has pioneered the adaptation of international crops and cattle ranching to Brazil’s tropical and semi-arid regions, a key factor behind the country’s success in recent decades. Brazil has also pioneered a range of low-carbon agriculture technologies, and some states have successfully mobilized international support to reconcile productive land use with preservation of forests and native vegetation. Brazilian producers, supported by world-class publicly funded agricultural research, have developed technologies that, if widely deployed, would allow Brazil to increase production at least twofold without the need to further reduce its globally significant forest resources.

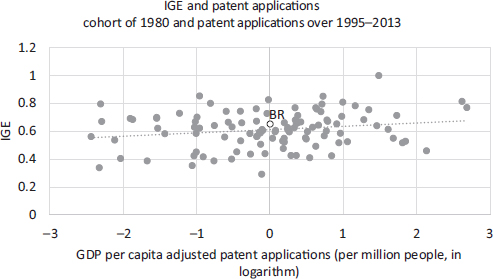

Across the world, productivity growth offers the opportunity to reduce poverty, foster shared prosperity, and enhance social mobility. Globally, higher productivity growth has been associated with a greater increase in shared prosperity. Between 2004 and 2014, the income of the bottom 40% of the population increased faster in countries with more rapid productivity growth (Figure 11.13). As emphasized by Milanovic (2016) among others, the process of globalization has been extraordinarily beneficial for the world’s poor. Innovation has also been a driver of some measures of social mobility in various OECD countries, including in Finland and the United States (Aghion et al., 2016, 2017). Across the globe, the cohort of people born in the 1980s experienced greater social mobility in economies that had higher patent applications per million inhabitants, controlling for GDP per capita in constant 2010 U.S. dollars (Figure 11.14). An increase of 10% in country patent applications per million inhabitants is associated with a 0.42% higher social mobility. Brazil, too, experienced rapid poverty reduction, but this was achieved despite slow productivity growth and started to revert once favorable external conditions receded.

Many around the world are concerned that recent technological advances may reduce rather than increase economic opportunities for the poor and vulnerable. Innovation is accelerating globally, with some technological changes now taking place at an exponential rather than linear pace and yielding new opportunities from industry 4.0 trends such as artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of things, autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, and other advances. These technological shifts may displace unskilled workers, change the patterns of trade, and thus create risks for the poor and vulnerable (Hallward-Driemeier and Nayyar, 2017).

However, these concerns may be less relevant for Brazil than for advanced economies. Brazil’s distance to the productivity frontier is sufficiently large that the effects of technology adoption on enterprise competitiveness and through this on output and demand for workers likely offset any negative impacts on employment from relative price effects and substitution away from lower-skilled workers. In other words, Brazil still has plenty of opportunities to lift all boats through catching up, as has occurred in many emerging markets over the past three decades (Milanovic, 2016).

Figure 11.14 Countries with higher patent applications have greater social mobility

Source: Vijil et al. (2018).

There is also evidence that greater innovation is directly associated with improved opportunities for social mobility. For example, the cohort of Brazilians born in the 1980s living in states with higher patent applications per million inhabitants (controlling for state GDP per capita, constant PPP 2010) experienced higher social mobility; an increase of 10% in state patent applications per million inhabitants is associated with a 0.73% higher social mobility (Figure 11.15). A similar positive association with greater social mobility exists for Brazilians who live in states with relatively greater access to the Internet. Given that entrepreneurial talent is evenly distributed across the population, innovation opens the door for less well-off individuals to move from low to high income within one generation. A business environment that spurs innovation by new entrants (instead of protecting incumbents) is among the potential drivers of this positive relationship.

The reforms needed to provide benefits from the new opportunities created by technological advances are the same as those needed to boost domestic integration and global competitiveness. Focusing on the impact of new technologies and shifting patterns of globalization on manufacturing-led job development in developing countries, Hallward-Driemeier and Nayyar (2017) emphasize that manufacturing can remain an important part of a successful development strategy, but the dual benefits of productivity gains and job creation for unskilled workers may come in somewhat different combinations. Services enhanced by digital technologies also will likely provide new opportunities, both tradable services on their own, such as financial, ICT, and business services as well as services embedded and bundled with manufacturing goods (or “servicification”), such as in pre-production R&D and design and in post-production advertising and marketing, apps on electronic devices, and after-sales consulting. Yet these productivity-enhancing products may generate fewer low-skilled jobs at given output levels than less digitized manufacturing processes. Hallward-Driemeier and Nayyar (2017) make the case that these challenges require countries to emphasize with even greater urgency the competitiveness of their business environment, the capabilities of their workers and firms, and their connectedness to global markets.

Figure 11.15 IGE and patent applications cohort of 1980 and patent applications over 1995–2013

Source: Vijil et al. (2018).

For Brazil, this means that reforms lowering the costs of doing business and supporting adoption of new technologies, including building absorptive capacity through education and management upgrading, are urgent. Opportunities risk shifting to other countries. The lack of connectedness and lower levels of capabilities of workers and managers are challenges in Brazil that, if left unaddressed, could jeopardize the realization of these opportunities in both services and “servicified” manufacturing. As discussed in the previous section, Brazil is one of the countries with the highest cost of adopting digital technologies. Removing tariffs and special taxes on ICT goods and services could lower prices and increase business and end-user demand. Education and training policies will need to adapt to exploit ongoing global technological change. The changes in the skills demanded by Brazilian employers require prioritizing innovation policies, changes in education and training policies, more flexible labor markets, and increased investments by firms to allow Brazilian companies to take full advantage of new opportunities.

In addition to supporting workers directly through active labor market policies, competition policy, access to finance, and measures to facilitate the establishment and growth of new firms can considerably ease the adjustment burden and create new opportunities. Competition policy has an important role to play to ensure that consumers benefit from lower prices as a result of market integration. For instance, the Brazilian competition authority (CADE) has recently investigated potential anti-competitive practices in the markets for cement, LPG, retail fuel, and salt – all products directly consumed proportionally more by poorer workers (such as LPG) or indirectly affecting relatively more the poor. More generally, policies to reduce barriers to entry and growth of new firms and to cut the operating costs for all businesses can boost the net employment gains from increased competition by allowing high-performance companies to rapidly expand output and create more jobs. Overcoming market failures such as information barriers could have a particular positive impact on more innovative companies. The redesign of business-support policies along these lines is discussed in the next chapter.

New technologies and government support for technological upgrading can preserve jobs by increasing competitiveness even in industries facing potentially higher competition from abroad. In principle, there are opportunities for upgrading firm capabilities in all industries, including those that have traditionally been viewed as having low technological content. The evolution of Compania Hering, a large textile and garment company, contradicts the image of this industry as being static, relatively backward, and only surviving behind a high protective tariff wall. It illustrates how support entities like SENAI could promote innovation even in industries where technological development is assumed to play a limited role. SENAI may wish to consider adapting its existing high-tech spaces (Institutos SENAI de Inovação or ISIs) so that they can promote productivity upgrading in all industries, including traditional industries such as textile and garments. SENAI may also wish to consider broadening the education of manpower in a way that would enable graduates to move into other industries if and when industries such as textiles and garments decline (Piore and Ferreira Cardoso, 2017).

Accelerating productivity gains to allow inclusive economic growth requires significant changes in policies and institutions. This chapter has shown that there is little prospect of sustained income gains in Brazil without enhancing competition and tackling the vast policy-induced barriers to productivity growth. This requires a significant change in public policies across a range of areas, reorienting state intervention, and creating greater space for Brazilian firms to compete in domestic and international markets. In addition, policies to support the necessary adjustment of workers and firms and shelter those unable to benefit immediately from new opportunities are needed as a complement.

International experience suggests that virtually no country has achieved high income levels without effective business-support policies, but this requires functioning institutions that minimize rent seeking. Thus, dismantling the existing policy framework in Brazil should not mean the elimination of all state support. Instead, the focus of reform should be on changing institutional frameworks to ensure the design and implementation of policies that promote competition and innovation, facilitate economic and social adjustment, and avoid rent seeking.

Strengthened institutional arrangements to design, implement, and coordinate better government actions are required to support the policy shift advocated in this chapter. For it to succeed, policymakers will need to overcome the resistance of powerful vested interests and champion a new role for the state in the economy. Brazil’s state has the ability and talent to drive this process forward. Yet it gets little return from the large institutional apparatus it has created. Political incentives drive short term and often rent-seeking behavior. And fragmentation leads to the poor coordination of policies across ministerial portfolios as well as across all levels of government. To overcome these constraints, new institutional arrangements are needed, based on the principles of transparency regarding policy design and implementation, policy contestability linked to rigorous evidence of impact, and improved coordination of policies both within government and between government and business.

At the heart of the changes advocated in this chapter is a different relationship between businesses and the state. Addressing the lack of competitiveness of many enterprises, in addition to creating adequate incentives and a competitive environment, requires a rethinking and rebalancing of existing business-support policies. Policies need to shift from transaction and compensation to addressing the key constraints to competitiveness – including strengthening firm capabilities for innovation and competitiveness and prioritizing technology adoption and diffusion while facilitating the adjustment of uncompetitive incumbents. This requires rebalancing public initiatives from their current sectoral focus to broad innovation support – including management upgrading programs, programs that strengthen linkages from local suppliers to GVCs and large enterprises, and programs that facilitate technology adoption. It also requires moving from generic R&D tax incentives, which are costly and ineffective, to target potentially innovative ventures with evidence-based policy instruments. Only if augmented by a different set of business-support mechanisms will the changes in economic incentives resulting from the removal of policy-induced distortions achieve their full effect.

Acemoglu, D., Akcigit, U., Alp, H., Bloom, N., & Kerr, W. (2017, November). Innovation, Reallocation and Growth. Mimeo.

Aghion, P., Akcigit, U., Hyytinen, A., & Toivanen, O. (2017). Leaving the American Dream in Finland: The Social Mobility of Inventors. Mimeo.

Aghion, P., Akcigit, U., Bergeaud, A., Blundell, R., & Hemous, D. (2016). Innovation and Top Income Inequality. Mimeo, Harvard.

Barbosa Filho, F.H., & Pulo Correa, P. (2017). Distribuição de produtividade do trabalho entre as empresas e produtividade do trabalho agregada no Brasil. In A Anatomia da Produtividade no Brasil, ed. R. Bonelli, F. Veloso e Armando, & C. Pinheiro. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, pp. 109–142.

Bartelsman, E., Haltiwanger, J., & Scarpetta, S. (2013). Cross-country differences in productivity: the role of allocation and selection. American Economic Review 103(1): 305–334.

Bloom, N., Eifert, B., Mahajan, A., McKenzie, D., & Roberts, J. (2013). Does Management Matter? Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(1): 1–51.

Bloom, N., Lemos, R., Sadun, R., Scur, D., & Van Reenen, J. (2014). The New Empirical Economics of Management. Journal of the European Economic Association 12(4): 835–876.

Bloom, N., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2016). Management as a Technology? Stanford: Mimeo.

Brambilla, I., & Tortarolo, D. (2018). Investment in ICT, productivity and labor demand: the case of Argentina. Policy Research Working Paper No. 8325, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Bravo-Biosca, A., Criscuolo, C., & Menon, C. (2013). “What Drives the Dynamics of Business Growth?” OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers No. 1. Paris: ECD Publishing.

Devereux, M., & Guceri, I. (2015). Can ‘the Good Law’ get better? An impact study of Isenção Fiscal em Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento, ‘the Good Law.’ Mimeo, Centre for Business Taxation, University of Oxford.

De Vries, G.J. (2014). Productivity in a distorted market: the case of Brazil’s retail sector. The Review of Income and Wealth 60(3): 499–524.

Dutz, M. (2018). Jobs and Growth: Brazil’s Productivity Agenda. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Dutz, M., Barroso, R., Basto, J.B.T., Fleischhaker, X.C.C., Nucifora, A., & Vijil, M. (2017). Business Support Policies in Brazil: Large Spending, Little Impact. Background paper to Um Ajuste Justo: Análise da eficiência e equidade do gasto público no Brasil. Brasilia: World Bank.

Endeavor B. (2017). Índice de Cidades Emprendedoras – Brasil 2017. Sao Paulo: Endeavor Brasil.

Foster, L., Haltiwanger, J., & Krizan, C.J. (2001). Aggregate productivity growth: lessons from microeconomic evidence. New Developments in Productivity Analysis: 303–372.

Foster, L., Haltiwanger, J., & Krizan, C.J. (2006). Market selection, reallocation, and restructuring in the U.S. retail trade sector in the 1990s. Review of Economics and Statistics : 748–758.

Fuentes, R., & Mies, V. (2017, October). Technological Absorptive Capacity and Development Stage: Disentangling Barriers to Riches. Mimeo.

Hallward-Driemeier, M., & Nayyar, G. (2017). Trouble in the Making? The Future of Manufacturing-Led Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hsieh, C.-T., & Klenow, P. (2009). Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India. Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(4): 1403–1448.

Hsieh, C.-T., & Klenow, P. (2014). The life cycle of plants in India and Mexico. Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(3): 1035–1084.

Iacovone, L., & Pereira-Lopez, M. (2018). ICT adoption and wage inequality: evidence from Mexican firms. Policy Research Working Paper No. 8298, World Bank, Washington, DC.

IADB (Inter-American Development Bank). (2017). Assessing Firm-Support Policies in Brazil. Office of Evaluation and Oversight. Washington, DC: IADB.

Kannebley Jr., S., & Porto, G. (2012). Incentivos fiscais à pesquisa, desenvolvimento e inovação no Brasil: uma avaliação das políticas recentes. Discussion Paper, No. 236, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC.

Klapper, L., Laeven, L., & Rajan, R. (2006). Entry regulation as a barrier to entrepreneurship. Journal of Finance 82(3): 591–629.

Maloney, W., & Sarrias, M. (2017). Convergence to the Managerial Frontier. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 134(C): 284–306.

Milanovic, B. (2016). Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. Belknap Press.

Miller, B., & Atkinson, R. (2014). Digital Drag: Ranking 125 Nations by Taxes and Tariffs on ICT Goods and Services. Mimeo, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), Washington, DC.

Ospino, C. (2018). Broadband Internet, labor demand and total factor productivity in Colombia. Policy Research Working Paper No. 8318, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Piore, M., & Ferreira Cardoso, C. (2017). SENAI + ISIs: the Silicon Valley consensus meets organizational challenges in Brazil. MIT-IPC Working Paper No. 17–005.

Reis, J.G., Iootty, M., Signoret, J., Goodwin, T., Licetti, M., Duhaut, A., & and Lall, S. (2018). Brazil’s Globalization and Integration of Output Markets Agenda. Mimeo, Washington, DC: World Bank.

Restuccia, D., & Rogerson, R. (2017). The causes and costs of misallocation. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(3): 151–174.

Stone, S., Flaig, D., & Messent, J. (2015). Emerging policy issues: localisation barriers to trade. Working Party of the Trade Committee, TAD/TC/WP(2014)17/FINAL, OECD, Paris.

Sturgeon, T., Chagas, L.L., & Barnes, J. (2017). Rota 2030: Updating Brazil’s Automotive Industrial Policy to Meet the Challenges of Global Value Chains and the New Digital Economy. Cambridge, MA: Industrial Performance Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Syverson, C. (2011). What determines productivity? Journal of Economic Literature 49(2): 326–365.

Vasconcelos, R. (2017). Misallocation in the Brazilian Manufacturing Industry. Available from: http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/bre/article/view/61801.

Veloso, F., Matos, S., Ferreira, P., & Coelho B. (2017). O Brasil em comparações internacionais de produtividade: uma análise setorial. In Anatomia da Produtividade no Brasil, ed. R. Bonelli, F. Veloso, & A. Pinheiro. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, pp. 63–107.

Vijil, M., Amorim, V., Dutz M., & Olinto P. (2018). Productivity, Competition and Shared Prosperity. Mimeo.

Zylberberg, E. (2016). Redefining Brazil’s Role in Information and Communications Technology Global Value Chains. MIT-IPC Working Paper 16-003. Cambridge, MA: MIT.