Upgrading, defined as a sustained, generalized transition into higher-value-added products with growing efficiency and local content (Doner, 2009), is an increasingly elusive challenge facing manufacturing industries in developing economies. The growing stringency of rules within the global trading system, coupled with a trade slowdown (Auboin and Borino, 2017), widening technological gaps, and the emergence of China as a crucial player, has worked towards restricting the space for developing countries to stimulate local development through traditional industrial policies (Rodrik, 2015; Haque, 2007).

In this context, the only available avenue for upgrading appears to be the type of learning that the GVC literature, relying on governance-centric frameworks, has assumed to take place when developing country firms interact with MNC buyers. However, recent work has been skeptical of these benefits to developing country firms, noting instead that “induced searches” usually triggered by events of vulnerability in developing countries are more likely to spur upgrading (Pipkin and Fuentes, 2017).

This more recent work has found that firms in institutional environments with oligopolistic markets and state institutions of limited capacity (Schneider, 2013; Fuentes & Pipkin, 2016) tend to be subject to learning-averse inertia that can be broken only when firms face shocks or other conditions of vulnerability. It is only at such times that learning episodes are triggered and firms embark upon searches to innovate.

While these studies have made substantial progress in identifying sources of learning and elucidating how the state’s institutional capacity factors into these processes, they reproduce an assumption that has been both prevalent since the early industrial policy literature, and echoed by the GVC literature regarding the preexisting level of institutional capacity (in the case of the state) and absorptive capacity (in the case of firms) that is required in order to have successful innovation. In both cases, a high level of institutional or absorptive capacity2 appears to be an indispensable precondition for upgrading: in the industrial policy literature, state bureaucracies must display considerable institutional capacity to coordinate and administer services. Meanwhile, in both the FDI literature and GVC studies local firms must exhibit absorptive capacity in order to upgrade into profitable value chain segments, within the bounds permitted by the governance structures of value chains. Without absorptive capacity, firms are often stuck in low entry barriers and low margin segments, where they are often engaged in a race to the bottom of little value for innovation.

But what of contexts where no such options – either institutional or absorptive capacity – are available? The new industrial policy literature, where public/private coordination generates collective searches geared towards problem-solving (Cimoli, Dosi, & Stiglitz, 2009; Mazzucato, 2013; Sabel et al., 2012), and the new “induced search” framework (Pipkin & Fuentes, 2017) admit the possibility of upgrading and increased state capacity in imperfect settings. However, in both cases the likelihood that contexts with low institutional capacity or inadequate previous state experience will see innovation continues to be very low. Despite the literature’s efforts to prove otherwise, this reproduces a deterministic stance regarding the possibilities of innovation where neither private nor state actors have preexisting institutional capacity or experience in the problem at hand.

Brazil’s experience with pharmaceuticals provides an interesting case to examine the dynamics of upgrading in a context where neither absorptive nor institutional capacity is present. Consisting of an oligopolistic market where throughout the 20th century state institutions had limited capacity for either support or monitoring, pharmaceuticals featured a long history of lackluster performance, low capabilities behind low-road practices, and organized resistance to demands for quality control and modernization. However, generic drug3 introduction after 2000 enabled rapid upgrading among previously underperforming local firms, as well as a move towards exporting, foreign investment, and innovation.

One of the champions of this wave was EMS, currently the largest pharmaceutical firm in Latin America, with presence in Europe and North America, geared towards innovation in higher-value-added products such as biologics. Far from an isolated case, EMS is among a group of local companies whose reversal of fortunes after entry into generics enabled innovation efforts in more complex products. Until then, a handful of multinational firms held about 80% of the market, while hundreds of local firms held about 20% between 1970 and 2000. As of 2018, according to Bureau van Dijk’s corporate database the top seven local companies boast a total of 187 patents in the local market, versus, for example, six in machinery manufacturing, and 30 in plastics, considering the local firms among the top ten producers in other “transformation industries.”4 Following their turnaround in performance and quality, these previously underperforming firms have gradually pursued collaborations with universities, other firms, and the state to develop innovations. Their initial transformation via collective learning has improved the chances of focusing more recent industrial policy onto clearer targets, a feature of success stories mentioned in this volume (see chapter by Limoeiro and Schneider).

Building on the “induced search” framework, this chapter examines the role of a shock as a trigger for a process of collective learning leading to innovation, focusing on a case with low state and private institutional capacity. In the context of extreme technological gaps, low institutional capacity, and political domination by large economic groups, firm behavior can take the properties of an institutional trap. In this sense, the observed “inertia” of widespread low-road practices becomes a self-reinforcing phenomenon, where only a sufficiently large shock and effective collective efforts to build industry-wide public goods can induce firms to innovate.

In turn, by fostering problem-specific public/private interaction, collective learning incrementally builds institutional capacity among relevant state actors. Thus, this chapter closes the “loop” identified in the literature, by tracing the evolution of both firm and public-sector capabilities in what would have been, a priori, an unlikely scenario for innovation.

The chapter is structured as follows: the second section offers an overview of the pharmaceutical industry in Brazil, examining the specialization trajectory of firms and the emergence of false starts of learning in the context of technological gaps, political domination by large groups, and a lack of state institutional capacity. The third section describes the “shock” that induced vulnerability in firms’ strategies, and analyzes the process of collective learning it created. The fourth section then traces the effects of collective learning on firm trajectories, finding that the former enabled a rapid reversal of the marginalized position of local firms and a realignment of industrial and health policy goals. The fifth section concludes the chapter.

Until the late 1990s, the lackluster evolution of pharmaceuticals in Brazil was, as in many developing countries, marked by the juxtaposition of two seemingly conflicting goals: providing support for local industrial development on one hand, and ensuring access to medicines on the other (Shadlen & Fonseca, 2013). The latter was particularly pressing, as historically medicines were a luxury for the rich. In 1995, 2% of the population accounted for more than half of the pharmaceutical sector’s revenue, while 51% of the population accounted for 16% (Barros, 1999).

Two salient features of the industry interacted with demand-side pressures to determine local firm trajectories for more than four decades. First, a widening technological gap in the early postwar period cemented the rise of an international pharmaceutical industry with production capabilities that were absent in Brazil. Until then, small-scale local laboratories had transformed substances of animal and vegetable origin into ointments and balms. The emergence of synthetic approaches to antibacterial drugs created new classes of antibiotics using production techniques that quickly left Brazilian laboratories behind, just as foreign firms arrived.

Second, as multinational presence increased in the context of a widening technological gap, a lack of common goals across the industry prevented the emergence of a coalition behind upgrading similar to the “triple alliance” experienced in the petrochemical industry (Evans, 1979). Both MNCs and local laboratories had a tense relationship with the government over price controls but were divided on IP and industrial policy. Despite underlying tensions within trade associations, relations between local and multinational firms were relatively cordial (Gereffi & Evans, 1981), because politically it was in the interest of both for a national industry to exist, and because some of the larger local firms maintained supplier relationships with multinationals.

By 1977, MNCs had displaced local industry and acquired 34 of the largest laboratories (Gereffi, 1983). MNCs had also replaced local firms in the more technologically advanced stages of production, dividing the industry into two groups: a handful of MNCs that by then controlled 85% of production and the totality of the prescription market; and a large number of locally owned small and medium-size enterprises with scarce capabilities and financial resources. Together, hundreds of local firms held about 20% of the market until 2000.

In this context, attempts at fostering learning proved elusive. They were characterized by short-lived bouts of support for industrialization (through, for example, a lax approach to IP), coupled with price controls, and defined by political struggles between a few influential multinational interests and fragmented coalitions of numerous, but weaker, local contenders. Two vehicles for industrial policy aimed broadly at import substitution – the Executive Group of the Pharmaceutical Industry (Geifar) in 1962, and the Central Drug Agency (CEME) in 1971 – failed following substantial pressure from Abifarma, the industry’s most powerful industrial association, considered the voice of multinational firms in practice, despite its mixed membership. Abifarma’s central narrative depicted foreign firms as innovators and advocates of stringent IP, while local firms were low-road imitators with suspect quality practices.

Exacerbated by the perceived nationalistic slant of organizations such as CEME, these internal tensions prevented the emergence of what Evans (1979) has called a “triple alliance”5 of local and foreign capital with state-owned enterprises, a configuration of interests credited with supporting industrialization in sectors such as petrochemicals. Evans (1979) notes that CEME’s inability to become a potential ally and form collaborations typical of the “triple alliance” ultimately diminished the organization’s survival chances. Envisioned as a centralized system to purchase and distribute medicines among the poor as well as a boost to public laboratories, CEME sourced from all firms, although its purchases were partially designed to stimulate local companies. Abifarma lobbied against CEME, accusing it of displacing private activity. Between allegations of corruption, inefficiency, and political pressures, the agency shed most of its research and development functions by the late 1980s, focusing on its role as a purchaser (Bermudez, 1994).

Similarly, import-substitution-era protection deployed throughout the 1980s failed to induce learning among local companies. Despite macroeconomic instability, the industry benefited from support to promote verticalization, increasing technological content, and an expansion of local participation in more complex stages of production. However, there were only marginal increases in the production of raw materials, productivity fell, and local firms remained stagnant. The move towards market-based incentives in 1988 boosted MNCs, while among local firms it spawned deindustrialization and a wave of closures and acquisitions.

Beyond the role of demand pressures given the politically sensitive nature of medicines in a context of widespread inequality, three points that emerge from these failed attempts illustrate the challenges of building local capabilities under the middle-income trap. First, we have the significance of trade association Abifarma as the industry’s main private-sector interlocutor and powerful influencer of health surveillance and sanitary policy.

Behind the scenes, Abifarma often blocked unwanted resolutions, bribed Ministry of Health officials to accelerate the drug registration process, and dictated hiring practices within the Secretaria de Vigilancia Sanitaria (Souto, 2004). The fact that Abifarma’s membership also included local firms failed to galvanize opposition to these practices, as many of these firms maintained supplier relationships with multinationals and therefore did not oppose the agenda.

Second, the state’s low level of institutional capacity was particularly troubling in the context of its dual role as supporter and monitor of the industry. In its supporter role, the state had, as noted by the failure of industrial policy vehicles, little consistency or effectiveness. The sanitary surveillance and fiscalization functions under the Ministry of Health were, despite repeated attempts at reform, riddled with corruption and inefficiency as well as an inability to enforce quality regulations in the industry. In effect, the secretariat was seen as a rubber stamp to speed up registration processes for larger, often foreign firms, and was suspected of controlling the revolving door of short-lived political appointments therein (Piovesan, 2002; Souto, 2004).

Finally, macroeconomic conditions and the fickleness of industrial policy reinforced local firms’ focus on the short term. While in poorer India, the state was able to use instruments that on the surface were similar to those deployed at times by Brazil (public procurement, price controls, lax IP), a weaker currency in 1960s and 1970s India left the country with fewer options to import, forcing it to develop internal capabilities in API manufacturing and scaling up. The multiple exchange rate system behind import substitution also facilitated the entry of foreign capital as well as intermediate chemical imports to Brazil, encouraging firms to buy rather than build internal capabilities.

With extensive technological gaps, the predominant specialization trajectory centered around the least complex stages of production of small molecule drugs; in particular, product development and research took a back seat to capability building around commercialization. In contrast to Indian firms, Brazilian firms “learned” to copy the commercial logic of MNCs (Guennif & Ramani, 2012), investing large amounts in advertising.

Demand segmentation under widespread inequality reinforced the focus on marketing expenditures over production capabilities, resulting in a distorted cost structure vis-à-vis the average pharmaceutical firm outside Brazil (Frenkel, 1977). The wealthier segments consumed MNC-made brand medicines obtained through prescriptions from physicians who, given uncertainties about quality, tended to trust the reputation of international brands. The latter’s prices were inaccessible to most Brazilians, many of whom did not have regular access to doctors and relied instead on often-untrained pharmacists. These poorer segments had only sporadic access to medicines and inevitably bore the brunt of less expensive but often substandard products peddled by pharmacists.

Deepened by the secretary of health’s lack of capacity to either monitor or enforce regulations on firms and pharmacies,6 this uncertainty about medicine quality exacerbated the proliferation of marketing practices. As in most developing countries, the three steps that comprise production capabilities or the “quality tripod” in pharmaceuticals (good manufacturing practices, pharmaceutical equivalence, and bioequivalence) were far from institutionalized in Brazil until the turn of the century. In São Paulo, where most of the industry is concentrated, only 24% of plants operating in 1995 were found to be in compliance with good manufacturing practices, the lowest rung of the “quality tripod” (Vigilancia Sanitaria, 2000).

As MNCs focused their lobbying and marketing efforts on the profitable premium prescription market, they justified their high margins by blaming local laboratories for the prevalence of low-quality drugs. Thus, although they were not themselves exempt from low-road practices regarding quality,7 MNCs waged public campaigns that leveraged their reputation as innovators against criticism for high prices.

Instead of investing to improve product quality, local firms reacted by spending increasing amounts on marketing efforts targeting lower-end consumers via pharmacists. Called empurroterapia, this practice consisted of offering deals (such as two for one, etc.) to pharmacists as incentives to peddle their products – copies that were “similar” to MNC drugs but lacked quality guarantees. Thus, large numbers of local companies (all private and family-owned) became stuck at the low end of the market by competing against one another for less profitable segments such as OTC drugs and similares.

These practices escalated into a war that fueled deindustrialization (Magalhaes et al., 2003), particularly as import-substitution-era protection drew to a close in the late 1980s and market liberalization ensued. Escalating cost meant that marketing became at once costlier and more crucial to short-term firm survival than investments to improve products. This fostered interdependence between the strategies of local companies and those of MNCs.

Democratization brought along increasing pressures for the industry. While the 1988 Constitution contemplated reforms towards universal health care, freedom of press and increasing participation by consumer defense and other civil society groups put a magnifying glass over product quality and sanitary surveillance practices. Meanwhile, price liberalization, increasing trade openness via Mercosul negotiations, the loss of industrial policy, and impending changes in IP regimes had important implications for the operating practices of the industry.

Less stringent price controls triggered soaring drug prices and mostly benefited MNCs. The IP debate and the loss of industrial policy also benefited multinational firms, which doubled their efforts to wage campaigns about the low quality of Brazilian medicines to justify their higher prices. Most local firms, in contrast, experienced increasing fragility. Disappearing protectionism, the prospect of IP stringency, and competition from lower cost Mercosul neighbors and increasing imports of semi-finished medicines translated into further deindustrialization.

Similarly, liberalization left public agencies that traditionally interacted with the sector – such as sanitary surveillance technicians and industrial policy supporters from BNDES and FINEP – in disarray. In this context, the Camaras Setorial, or industrial councils, became the only forum of exchange with the government for these displaced public-sector agencies as well as the private sector and labor. Operating between 1988 and 1995, the Camaras8 were originally conceived as an instrument of industrial policy, but later evolved to accommodate shifting political priorities during the Collor era.9

There was initially one Camara for the entire chemical complex – a contentious aspect given the domination of the space by petrochemicals, its most developed industry. Members of the latter were more numerous, diversified, and closer to the technological frontier than those in pharmaceuticals. Final markets, cost and employment structure, and levels of integration among petrochemical firms were also markedly different, which created power asymmetries and prevented the emergence of sectoral agreements, relegating the concerns of the pharmaceutical industry. As the most vulnerable members of the Camara, local pharmochemical and pharmaceutical firms were, unlike petrochemical firms, uniquely affected by trade liberalization and imminent changes in IP. They initially resorted to supporting the demands of the petrochemical complex, in the hopes of securing the latter’s support for IP flexibility and the continuation of import-substitution-era protection. However, once the latter’s demands were addressed, the petrochemical group led by Petrobras exited the negotiations, leaving other producers in a frantic search for allies.

These internal distinctions among the different industries lumped together under the Chemical Complex Camara precluded the possibility of a comprehensive sectoral agreement of the type reached by the auto sector, where size, value chain homogeneity, and an ample participation of labor facilitated negotiations. None of this was true of the chemical sector, where beyond the role of Petrobras for petrochemicals, influence was much more diluted in fine chemicals; labor represented a much smaller portion of operating costs, and unionization rates differed considerably between local and foreign companies (Teodosio & Camara, 1996).

Beyond the considerable gap in organization and influence between petrochemicals and the rest of the Camara, vast differences in performance and institutional capabilities, and even incentives, existed within fine chemicals industries themselves. Local pharmochemical actors (represented by the association Abiquif) were better organized than those in pharmaceuticals, yet their superior levels of vertical integration left them more exposed to trade openness. Meanwhile, the MNC leadership of pharmaceutical associations was peripheral to the Camara, since reforms had created a bonanza among MNCs. Both sets of vulnerable actors – local pharmaceutical and pharmochemical firms – began to actively participate in the Camara, in the hopes of erecting regulatory barriers against their Mercosul competitors. This inability of the pharmaceutical industry in getting their agenda across in the presence of the petrochemical industry resulted in the creation of a subordinate Camara dedicated to pharmochemicals and pharmaceuticals. The evolution of discussions within nudged local producers, who began to realize that their traditional discourse about industrial protection and flexible IP would no longer be an effective way to enlist government support, as the Collor era prioritized the rule of free markets and dismantled protectionism, albeit without a strategy to manage the heterogeneous impact of liberalization.

The political isolation of these actors and their reputation as industrial policy dependents vis-à-vis the more organized and technologically complex petrochemical industry fueled the desire, among local producers and labor, to demonstrate their technical competency and concerns for broader public health issues. Gradually, pharmochemical and pharmaceutical producers reframed their concerns in terms of technical issues and the public health value of their activities (Buchler, 2005). Along with disgruntled unions, and displaced BNDES and Secretariat of Industrial Policy technicians, these producers turned to the Sanitary Surveillance Working Group situated under the new Camara.10 Thus, not only was the scope of discussions narrower, but the content soon became much more technical as local producers tried to appear “modern” and technically competent vis-à-vis the state. However, as Mello e Silva (1999) suggests, it was also part of a broader producer strategy to remain above the demands of labor.

Individual preferences evolved around two sets of issues: the establishment of an external tariff (TEC) for Mercosul, which in turn required harmonizing the industrial nomenclature of participating countries; and the development of regulations to incorporate public health considerations into the Mercosul agreement, including guidelines for product quality. Most of this was done without significant state presence. Although the Ministry of Health – and the Secretariat of Sanitary Vigilance (SVS) within, in particular – was formally slated to lead rule creation, the disarray therein11 left many of these discussions without official participation.12 The overall public-sector crisis, and the recent battles of prices and quality, contributed to a convergence of local interests around the elaboration of a set of rules for GMP in medicine manufacturing.13

During the TEC negotiations, Brazilian pharmachemical and pharmaceutical producers struggled to embed the new guidelines within regulations for public health and drug safety, which were not fully developed in any of the member countries at the time. This posed a considerable challenge for firms whose largest shortcoming was a lack of capabilities and technical knowledge in the very field where they now had to elaborate comprehensive rules. At the same time, the opportunity to use quality regulations as a commercial barrier provided an incentive for learning, since producers in neighboring countries were fewer and less vertically integrated than those in Brazil (Buchler, 2005). This had generated fears that a customs union would enable smaller countries that lacked their own pharmaceutical sectors to import semi-finished products from non-member countries and pass them off as their own (Correia, 2001).

Within the Sanitary Surveillance Working Group, Abiquif spearheaded systematic efforts to collectively elaborate a set of guidelines for GMP between 1992 and 1994. This allowed for a reconfiguration of local interests around deliberative experimentation and the construction of institutions geared towards quality improvements. Remarkably, the participation in this working group was fundamentally local: participants included Abifina, BNDES, Alanac, Fiocruz, São Paulo’s Center for Sanitary Surveillance, the Secretariat of Industrial Policy of the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Tourism, São Paulo’s Chemical Workers Union, and Unified Workers’ Central, among others.14

Abiquif’s lead in the Camara translated into Mercosul as well, becoming instrumental in the agenda of the Common Market Group’s Working Subgroup 3 (SGT III), in charge of Technical Norms. The Camara’s early groundwork became the basis for the overall agenda that was approved by the Common Market Group in 1992 to bring the pharmaceutical sectors of each country to a common standard of quality and manufacturing practices by 1994.15,16 Abiquif’s early groundwork made the organization an unofficial leader of diverse local actors throughout the supply chain with regards to quality regulations.

In this context, the collective definition of norms became an experimental search: between the pervasiveness of low capabilities and the lack of government leadership, firm associations were forced to take a hands-on approach at understanding quality regulations. Precipitated by the lack of government leadership, the search for answers that ensued took place in a collaborative environment geared towards norm creation. The specificity of GMP criteria revealed in collective deliberations exposed the amount of inexperience among local producers, who realized just how haphazardly they had operated. At the same time, a document with theoretical rules would help firms only to a certain extent. These gaps could not be filled by the public sector, since there was a lack of trained inspectors with enough up-to-date knowledge to walk firms through the new set of requirements. As a solution, participating associations began to collaborate in the organization of mock inspections of their members’ factories. As one of Abiquif’s representatives explains:

The problem throughout was that you couldn’t treat this as a theoretical discussion: you had to visit the plants, see how things worked in practice … and part of it was understanding that the SVS wasn’t going to work, so firms themselves sought to be inspected.17

Thus, technicians from several local firms collaborated not only in norm creation, but also in helping familiarize smaller and less capable firms with the new procedures. The few local firms that had international experience with these procedures, such as FDA certification, guided their peers through mock inspections. These gradual efforts soon put Brazil ahead of its neighbors in terms of the implementation of Mercosul regulations for the sector. While other Mercosul producers passively received the new framework, Brazilian medicine manufacturers actively revised their practices beyond the proposed template. Further, the set of rules on good manufacturing practices elaborated by the Camara became the most important framework resulting from Mercosul in the pharmaceutical sector. The level of detail therein made this framework a model followed by other Latin American countries attempting to regulate their pharmaceutical sectors, and was even used as a reference by the industry itself in its operations throughout the hemisphere (Lucchese, 2001).

The initial GMP focus of the Sanitary Surveillance Working Group enabled fundamental transformations in local firms’ approaches to production capabilities by narrowing down the areas in need of adapting, providing both a collaborative environment and a roadmap of specific tasks that made the catching up problem more accessible to individual producers regardless of preexisting capability levels. Similarly, the collective exercise of the Camara provided an implicit subsidy to the individual learning activities of producers that would not otherwise be able to cover the cost of hiring GMP advisors. This was particularly important given the meager profits of the majority of local firms in this period.

The transformative effects of the Camara soon reached the public sector, particularly as the debate moved forward towards the harmonization of sector-specific technical regulations for Mercosul. As Lucchese (2001, p. 205) notes:

A unanimous view among those who participated in this process in its first five years was that the work devoted to integrating technical regulations bolstered the need to modernize, both in the public sector (through the perspective of facilitating the entry of neighboring countries’ products), and in the private sector, which sought satisfactory rules as well as to expand (or at the very least, preserve) their markets.

Changes in attitudes precipitated by the collective learning experience of the Camara reached Health Ministry representatives (Lucchese, 2001; Fontes, 2002) and unions (Buchler, 2005), and have been recognized as a source of policies such as the generics initiative and Farmacia Solidaria program.

The guidelines became embedded in Brazilian law, known as the Programa Nacional de Inspeção na Indústria Farmacêutica e Farmoquímica (PNIFF).18 While at the national level, these rules came into effect in 1995, by then several local firms had become familiar with GMP regulations and inspection procedures. Insofar as producers needed this law to keep out foreign low-cost producers, they perceived GMP regulations as a credible commitment from the state and took steps to internalize them.

While the Camara worked on GMP rules in 1993, Abifarma focused on challenging Decree 793, an attempt to introduce generics, using the same strategies that had predominated historically: waging a public campaign intended to warn the public about the low quality of off-brand products, while its firms simultaneously refused to comply with government directives. This strategy of collectively ignoring unwanted regulations until the latter’s political backers weakened served Abifarma well until the turn of the century. Abifarma’s challenge was based on quality concerns, which added fuel to efforts around GMP within the Camara. Yet another unintended consequence of Abifarma’s criticisms of the deficient quality of Brazilian firms’ products and the unreliability of the sanitary surveillance team as a watchdog was the systematization of the collective learning process among local firms after the Camara’s demise.

After the Camara, Sindusfarma’s relatively new local leadership reoriented the organization’s profile towards offering training and leading conferences and workshops to expose its membership to state-of-the-art knowledge in regulatory, commercial, and technical issues, particularly those related to international standards in pharmacovigilance.

In part, Sindusfarma had originally planned a shift towards training as a depoliticization plan to revamp the association’s image through local leadership. However, the fact that no systematic learning activities took place until the aftermath of Decree 793 in 1994 suggests that this may have been a form of lip service at first. Another aspect that is indicative of this strategy is that multinational firms and their associations (including Sindusfarma) had only marginal levels of participation in the Camara’s deliberations prior to 1994. Having remained on the sidelines of the detailed work on GMP by local associations, these groups seem to have been largely unaware of the subtle changes experienced by smaller companies.

Sindusfarma had condemned Decree 793, claiming that while it supported the eventual introduction of generics, the state of local capabilities and monitoring made it unrealistic. Sindusfarma criticized the decree’s failure to include stringent pharmacovigilance criteria, and specifically, the verification of bioavailability and bioequivalence. As the syndicate was aware, these concepts were entirely new in Brazil and out of reach for even the more advanced local companies.

Despite ongoing mutual accusations between the industry and the SVS, the technical basis of Sindusfarma’s criticisms began a dialogue with surveillance technicians that gained momentum with the designation of renowned scientist Elisaldo Carlini as head of the secretariat. Gradually, the rapport between Sindusfarma president Omilton Visconde (the founder of local firm Biosintética) and Carlini gave way to a collaborative relationship geared towards the creation of scientific standards for a national pharmacovigilance framework.

Sindusfarma’s new proactive approach translated not only into an intensification of its involvement in the Camara, but also into an increasingly central role within Mercosul’s working group for the harmonization of sector-specific technical regulations (SGT-III), a move that boosted technical exchanges with the SVS. As the Camara began to lose favor – and a wave of deindustrialization weakened the local pharmochemical associations that had been relevant in it – Sindusfarma’s guidance became more significant and acquired a sense of legitimacy among local entrepreneurs.

The charismatic leadership of Visconde was also instrumental in gaining the reluctant trust of local firms and the public sector alike. Elected as representative of the pharmaceutical industry before the Confederation of National Industries (CNI), Visconde took the opportunity to propel this capacity into a leading role during the 1994 meeting of the National Health Council (CNS), where he and Carlini elaborated a proposal with extensive technical criteria to design an independent agency of sanitary surveillance modeled after the American FDA.19

Although both sectors still traded accusations on product quality, there was an apparent convergence of interests between producers and the government, as Piovesan (2002) notes, which facilitated the actions of a still-feeble SVS. Unlike in previous years, the improved relationship between the SVS and the private sector was not built on a lax approach to monitoring. With the PNIFF in effect, Carlini’s team conducted 740 inspections of laboratories between 1995 and 1996, as well as 304 re-inspections, which led to the closure of 80 laboratories with deficient quality and the cancelation of 200 products.20

In this period, Sindusfarma hired Lauro Moretto, a former foreign pharmaceutical firm representative who was better known for his work as a USP professor. Moretto was in charge of elaborating a plan to transform the role of Sindusfarma into a provider of a collaborative learning environment for firms regardless of ownership, bringing an international focus. As Moretto explains: “The goal was not to compete with universities; we assumed the role of teaching what schools could not teach. We organized symposia on new themes, such as bioavailability.”21

Training activities included industry experts, public-sector representatives, and university professors. In addition, Visconde encouraged an interpretive environment within Sindusfarma by systematizing monthly meetings on regulatory developments. Open to all members, these meetings provided a space for sector-wide debate as well as a transparent channel for the collective interpretation of new government rules.

While the scarce resources of smaller firms had traditionally been behind the lack of investment in learning, part of the problem was, as the Camara’s experience also revealed, that a large sector of the industry remained unconvinced of the value of investing in learning activities. In turn, this created a distorted perception of the cost structure of learning that made future investments less likely. Thus, a considerable task of Sindusfarma’s coordination was persuading entrepreneurs of the indispensable nature of changes in practices. As one official notes:

At the beginning we had to assume all the costs: we couldn’t charge participants any registration fees because the industry was not yet ready to invest. So we worked with human resources personnel from different firms to convince them of how important these trainings were to their firms. Then, things started to evolve, and gain professionalism. Dr. Moretto hired specialists in each area, so that they would make the program more specific and work alongside conference experts.22

Between 1993 and 1999, Sindusfarma organized 61 events geared towards professional training that benefited a total of 2,530 attendees in the same period. Unsurprisingly, the bulk of participation (almost 50% of attendees) concentrated in events that tackled the low level of technical capabilities in Brazil in connection to international regulatory structures, while workshops, seminars, and conferences on external trade, labor relations, tributary issues, and worker safety drew participants in smaller numbers (Moretto, 2009) Starting with an expanded GMP framework that included logistics and phytotherapeuticals,23 the increasingly crowded workshops deepened the Camara’s work on good manufacturing practices and eventually moved towards more complex issues of pharmacovigilance.

Indeed, in April of 1994, Sindusfarma organized the country’s first symposium on bioavailability and bioequivalence of medicines, with a record attendance of 108 participants. As the next step towards quality assurance after GMP, these concepts provide technical criteria to ensure the effectiveness and comparability of medicines. In this sense, the resolution of these issues was indispensable for the upgrading efforts of local firms, which had no alternative way to access this knowledge. In the words of an Aché employee:

When I went to university in 1990, nobody talked about bioequivalence and generic medicines. I was only able to acquire that knowledge after I graduated. I took courses, went to conferences, but the most important knowledge, the most practical and up-to date concepts I learned at Sindusfarma. For us, having that experience is essential, especially if it gives us access to specialized professionals in the area, because we have to deal with these issues every day and need a practical way to know what works and what doesn’t.24

In addition to the systematic organization of educational events, Sindusfarma began to edit a series of manuals and handbooks that detailed quality control procedures (including guidelines for storage, supplier relations, product analytics, and specific rules for different product categories), and provided updated guidance on pharmaceutical legislation. These materials became a crucial reference for smaller local firms, as a number of interviewees suggest.

Overall, these efforts contributed to creating a critical mass of actors that were eventually willing to translate this knowledge into changes in operating practices. The Camara’s GMP work had provided an indispensable first step for firm learning about the “quality tripod” – with the systematization of a GMP framework, some of the most vulnerable local pharmaceutical operations adapted and ensured their survival. With this first step in place, a critical mass of local firms created demand for trainings within the trade association, and benefited from the collaboration of local and foreign experts from industry, government, and academia.

Since the chief criticism about the potential for generics introduction was that such products were not the same as the original medicines, much interest in these trainings went to the next two rungs of the capability ladder: pharmaceutical equivalence and bioequivalence. As the larger local firms improved their productive capabilities, some made early investments to ensure bioequivalence. These investments, derived from the Camara’s collective learning environment, became instrumental to upgrading. Investing firms ensured large gains in market shares by reacting more quickly to the 1999 Generics Law.

Given that the previous effort to introduce generics in 1993 had failed, few expected the 1999 law to succeed. MNCs were the first to vocalize their antagonism and run advertisement campaigns to prevent its enforcement. With their profit margins under threat, these firms claimed that the initiative was a low road that would result in poor-quality medicines flooding the market. Even some local firms, which ostensibly stood to gain from the law, had negative or mixed reactions to it, while others indicated that they needed years to adapt to the law’s bioequivalence requirements. All agreed that it would take years before generics actually entered the market. Preparing for a long battle without any local takers, Minister of Health Serra himself traveled to India in 1998 to attract generics manufacturers to Brazil. However, in the first three months after the law went to effect, six local firms and one foreign one registered 51 generic products.

From then onwards, the pharmaceutical landscape became markedly different. Four Brazilian laboratories entered the market’s top ten. Having been first movers in generics, three of these firms increased their revenue drastically. Many more local firms joined the top 20. All upgraded production, quickly complied with increasingly stringent certification regulations, and became more profitable at the same time. Meanwhile, surveillance agency ANVISA gained importance as a monitor of quality standards, and the number of counterfeit drugs in the market fell rapidly.

In the literature, the quick adaptation of firms to the new standards has remained unexplained; similarly, the institutional changes originated in the Camara, as well as the learning activities taken up by associations, have received little attention. Traditional explanations for the drastic turnaround in firm performance tend to fall in two camps: the market and the state story. In the first, changes in firm practices are considered as natural reactions to market signals such as the 1996 Patents Law and the 1999 Generics Law. There is no learning among firms, but merely a changing signal towards resolving appropriability that sees generics as easily accessible “low hanging fruit.”25

The state story divides into two subgroups: the industrial policy and the savvy politician story. The first credits BNDES26 with orchestrating upgrading among local firms, drawing from the 2003 PITCE framework. The second and most prevalent explanation emphasizes the role of Health Minister Jose Serra in promoting generics as a response to the AIDS crisis.27 This narrative sees Serra as a champion of state activism and advocate of the right to break drug patents during health crises, as well as of using generics to prop up local firms behind the scenes.

However, none of these explanations can account for the rapid adoption of high-road practices among local firms, particularly given the profound lack of capabilities that characterized them historically. Industrial policy entered the picture only in 2003, with an instrumental role in aiding industry consolidation and further innovation, but too late to have affected the initial shift in practices that enabled local firms’ entry into generics. Similarly, Serra’s rocky relationship28 with both local and foreign companies over the issue and his efforts to court Indian companies into providing generics suggest the rapid uptake following the Generics Law was surprising to the minister himself.

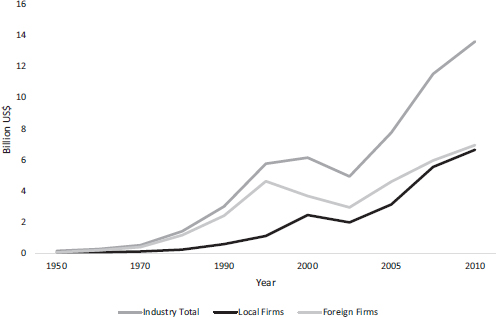

Here, the collective learning activities of the 1990s are linked to a turnaround in firm performance accompanied by innovation. Figure 14.1 shows the shift in the distribution of firm revenues (in constant 2005 US$) among local and foreign firms between 1950 and 2010; the leap in shares of local companies is an interesting feature of the post-2000 landscape. The Generic Law’s combination of strict requirements and familiar political conflicts uniquely offers an opportunity to test changes in behavior as well as performance, particularly those deriving from learning activities.

Given that early entry is the main predictor of individual share changes after the law, original data on early bioequivalence investments are used as an instrument to understand what determines early entry, through an original dataset with registration information for 1,272 products. Based on records of all bioequivalence and bioavailability testing conducted in Brazil prior to 2000 (that is, before such investments were legally required), this instrument traces investments directly connected to the collective learning activities spawned by the Camara Setorial in the dataset. Moreover, timing, content, and attendance data on collective learning activities – complemented by interviews – provide opportunities to connect investments by previously low-capability firms to collective initiatives.

The expanded model allows for unpacking movements along the “capability ladder” – where GMP knowledge represents an initial step and bioavailability and bioequivalence are advanced steps – while linking firm participation in collective learning in the 1990s to specific investments. This is facilitated by the fact that, until 2000, trade associations were the only source of information regarding bioequivalence for local firms, none of which conducted such tests before 1990.

The resulting model is:

LN _EntryTimei = β0 + β1Bioequivalence + β2Ownership + β3GMP + εi

Adding an interaction term to measure the joint effect of local ownership and GMP investments yields the following model, where the implementation of knowledge derived from collective learning by local firms explains 78% of the variation in entry timing following the Generics Law.

|

Coefficients |

Estimate |

Std. error |

t value |

Pr (> |t|) |

|

(Intercept) |

3.70746 |

0.05190 |

71.435 |

< 2e-16 |

|

Bioeq. yes |

−2.26381 |

0.04711 |

−48.049 |

< 2e-16 |

|

Ownership local |

−0.24901 |

0.10693 |

−2.329 |

0.02* |

|

GMP yes |

0.52265 |

0.07939 |

6.583 |

6.73e-11 |

|

Ownership local + GMP |

−1.40562 |

0.12885 |

−10.909 |

< 2e-16 |

|

Residual standard error: 0.7766 on 1,267 DF. Multiple R-squared: 0.7809, adjusted R-squared: 0.7802. F-statistic: 1,129 on 4 and 1,267 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16. |

||||

On average, firms that made innovative investments derived from collective learning activities ahead of the law entered the market earlier than other firms. As Figure 14.2 shows, these early bioequivalence investors experienced the largest positive changes in shares post-2000.

The difference in innovative bioequivalence investments between local firms directly exposed to collective learning and MNCs, which remained peripheral to discussions, emphasizes the influence of collective learning on firm behavior. Thus, and despite multinationals’ reputation for high-quality medicines, few of these laboratories implemented early testing, as Figure 14.3 shows.

This explains the apparent and often-cited “bias” of the Generics Law in benefiting local firms. In fact, the latter simply reacted faster, aided by quality-improving investments derived from the previous decade’s collective learning activities, in which multinational firms had been limited to no participation.

In sum, collective learning in the 1990s enabled the coevolution of informal institutions around quality. Collective learning appears to have propelled a shift in the three institutional functions that have been pointed out as indispensable to ensure upgrading and an escape from poverty traps, namely inducing cooperation, coordinating beliefs and complementary actions, and making credible commitments (Ang, 2016).

In Brazil, participation in early collective learning created the conditions to build the institutional function of inducing cooperation among firms, most significantly through a reframing of the agenda of industrial associations around the provision of quality-related knowledge as a public good. Examples of this include the coordination of mock plant inspections among local firms and associations such as Abiquif, as well as Sindusfarma’s systematization of training activities in the second half of the 1990s.

Similarly, the emergence of a group of first-mover firms whose participation in collective learning altered early investment strategies appears to have contributed to the institutional function of coordinating beliefs by inducing confidence in the new law and demonstrating profitability. These firms not only actively participated in workshops and other learning activities but also implemented these findings into early, innovative investments in testing. Their absorption of first-mover risk in implementing testing and entering the market early, which led to a rapid accumulation of market shares,29 helped convince other companies of the viability of generics, as well as change perceptions regarding the cost structure of learning.

In turn, this confidence in the new law contributed to ensuring its success in the face of familiar undermining collective action strategies, such as the ones that followed Decree 793. Coordinating beliefs could also help explain why these attitudinal changes towards quality, reflected on commercial and political practices around compliance with state directives, took place only among local firms, since foreign firms had a more subdued participation in the Camara. This explains the “expectation game” around the new Generics Law, and the inertia in reactions among multinational firms, which reproduced old political strategies since they did not believe their local counterparts had developed capabilities to be serious competitors.

In this context, the Ministry of Health’s pledge to expand access to medicines via generics and Anvisa’s role as a watchdog both performed an institutional function of making credible commitments that sped up the success of the Generics Law. As the following quote30 from a middle manager of a second-mover firm notes:

We Latinos create laws and then wait and see whether or not they will stick. In this case, when the industry saw that Anvisa was not going to grant registrations without bioequivalence, a lot of firms realized that they meant serious business.

At the same time, this new institutional capability displayed by Anvisa could itself be a partial result of Camara-era collective learning. This is because many of the technicians and officials that were instrumental in the design of the new agency took an active part both in Camara discussions around GMP and later throughout industry trainings. These technicians had themselves become vulnerable during a period when the Sanitary Surveillance Secretariat was criticized for its performance,31 and for what Piovesan (2002) refers to as its “low autonomy, administrative discontinuities, low technical capacity, and capture by private interests.”

With these three functions in place, the diffusion of a quality-based high road as the new norm of the sector was adopted by a wave of second- and third-comer firms. The gains of first-mover firms supported subsequent high-road practices (including exporting to and investing in innovation in highly regulated markets,32 conducting internal R&D and patenting, and manufacturing more complex products such as biologics, among others) that continue today.

Coordinating beliefs created a new cost structure of learning that stands in stark contrast with the one that had prevailed historically. Between 2000 and 2005, local firms reduced marketing expenditures by half and doubled their R&D expenditures in relation to net revenues, while foreign firms in Brazil increased marketing substantially and reduced their R&D expenditures.33

Similarly, while throughout the 1990s the sector’s spending on increasing GMP remained mostly unchanged – averaging only US$300,00034 per annum until 1999 – this figure grew to almost US$4 million in 200335 among companies with at least one generic product. A similar trend is visible in bioequivalence testing and new product registration, where overall investment went from just more than US$3 million in 1999 to US$23 million in 2000, climbing up to US$87 million in 2003.36 Among generics producers, the overall growth of learning-related investments at times outpaced investments towards expanding production capacity.

Finally, the sector’s transformation is visible in product quality. By the 2000s, the U.S. FDA estimated that Brazil had one of the lowest percentages of substandard and counterfeit drugs in Latin America, a notable feat given that poor-quality medicines still constitute an estimated 40% of production in Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico. In Brazil, less than 8% of all drugs in the market were considered substandard or falsified in 2012 (BMI, 2012); by 2018, this figure is estimated around 6% (Ozawa et al., 2018). Health surveillance data from São Paulo support these shifts. Between 1997 and 1998, serious irregularities were found in almost 200 products; between 1999 and 2006, however, this number dropped to 18. Similarly, although only 24% of industrial plants were found to be compliant with GMP in 1995, by 2000 70% of facilities passed the same inspection, while “offender categories” also registered significant improvements.

This study shows that upgrading is possible in the 21st century in the absence of the traditional preconditions in terms of institutional and absorptive capacity considered in the literature. During most of its postwar history, Brazil’s pharmaceutical industry seemed to be mired in a lackluster trajectory that was not unlike an institutional trap, where individual low-road behaviors had become interdependent and self-sustaining. The industry was marked by large technological gaps, an oligopolistic market structure, and a weak state that, in attempting to balance the demands of industrial development and medicine access under inequality and rising prices, failed to generate credible commitments either through industrial policy or as a monitor of the industry. Yet even in this context, a shock that threatened the behavior of the most vulnerable gave way to a fruitful process of collective learning that paved the way for both firm innovation and increased state institutional capacity.

The apparent impact of generic introduction on local firms and regulatory development was so stark that existing literature, ignoring the incremental and subtle learning of the collective learning process spurred almost a decade later, struggled to categorize it. Thus, the phenomenon was catalogued as either an industrial policy story (despite the fact that industrial policy was only introduced in 2003) or a scattered, seemingly obvious set of responses to a market signal. In cases that acknowledge some capability building (Guennif and Ramani, 2012; Shadlen and Fonseca, 2013), underlying learning dynamics are glossed over. Both cases see the Generics Law as a starting point for learning, yet they fail to explain how local firms that were so far behind basic rules of GMP just a few years earlier suddenly developed crucial technological capabilities.

The Brazilian case shows an incremental process of change that appears to have been successful in improving three institutional functions that are essential for policy effectiveness: credible commitments, inducing cooperation, and coordinating beliefs and complementary actions (WDR, 2017). In particular, the influence of collective learning on local firms’ coordinating beliefs would help to explain why MNCs did not seem to expect the Generics Law to have an immediate uptake. Having remained on the sidelines of learning efforts, most MNCs did not believe that local firms would be capable of complying with regulation so quickly.

Instead, MNCs reenacted through Abifarma the form of collective action they had become used to throughout the postwar period: resisting state enforcement of unwanted laws, disputing or collectively ignoring them until the state gave up enforcement efforts.37 This was the case, for example, when the government attempted to introduce generic medicines in 1993 and again in 1999; Abifarma waged a public campaign intended to warn the public about the low quality of off-brand products, while its firms simultaneously refused to comply with government directives. However, they met a changed environment, with transformed local competitors, as well as a state whose commitments were more credible, and linked to a system of complementary norms through a mandate to provide low cost, high-quality medicines to the poor.

The question remains whether the industry will be able to replicate the dynamics that first enabled innovation under an increasingly technologically, politically, and macroeconomically challenging environment. While there is a risk that firms may retreat into safe niches and “treadmill” (Pipkin and Fuentes, 2017), the industry has at this point amassed institutional capabilities that may be again repurposed, particularly considering the internal financial resources many upgraders have built.

Ang, Y.Y. (2016). How China Escaped the Poverty Trap. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Auboin, M., & Borino, F. (2017). The falling elasticity of global trade to economic activity: testing the demand channel. WTO Staff Working Papers No. ERSD-2017–09.

Barros, M.C. (1999). Antidumping e protecionismo. São Paulo: Aduaneiras.

Bermudez, J. (1994). Medicamentos genéricos: uma alternativa para o mercado brasileiro. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 10(3): 368–378.

Biehl, J. (2004). The activist state: global pharmaceuticals, AIDS and citizenship in Brazil. Social Text 22(3):105–132.

Business Monitor International. (2012). Brazil pharmaceuticals and healthcare reports. Retrieved from BMI research database.

Buchler, M. (2005). A Camara Setorial da industria farmoquimica e farmaceutica: uma experiencia peculiar. Rio de Janeiro Camara Setorial Records, Working Group on Sanitary Surveillance, Aug. 1993.

Bureau Van Dijk (BVD), Orbis (2018). Available at: Subscription Service (Accessed: July 2018).

Capanema, L. (2006). A indústria farmacêutica brasileira e a atuação do BNDES. BNDES Setorial, 23, 193–216.

Cimoli, M., Dosi, G., & Stiglitz, J. (2009). Industrial Policy and Development: The Political Economy of Capabilities Accumulation. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly. 35(1, Special Issue: Technology, Organizations, and Innovation) (Mar. 1990), 128–152.

Correia, T. (2001). O Mercado de Medicamentos no Brasil durante a década de 1990 e regulacao do setor farmaceutico. Monografia em Economia. Campinas: Unicamp.

Csillag, C. (1998). Epidemic of counterfeit drugs causes concern in Brazil. The Lancet. 352. August 15, 1998.

Diniz, E. (1993). Articulacao dos atores na implementacao da politica industrial: a experiencia das camaras setoriais – retrocesso ou avanco na transicao para um novo modelo? Estudo da Competitividade da Industria Brasileira. Campinas.

Doner, R.F. (2009). The Politics of Uneven Development: Thailand’s Economic Growth in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eisenberg, D., Davis, R.B., Ettner, S.L., Appel, S., Wilkey, S., Van Rompay, M., & Kessler, R.C. (1998). Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 280(18): 1569–1575.

Evans, P. (1979). Dependent Development: The Alliance of Multinational, State, and Local Capital in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Evans, P. (1983). State, local, and multinational capital in Brazil: Prospects for the stability of the Triple Alliance in the ‘80s. In: Latin America in the World Economy: New Perspectives, ed. D. Tussie. London: Gower and St. Martins.

Fontes, P. (2002). A quimica da cidadania. São Paulo: Viramundo.

Frenkel, J. (1977). Tecnologica e competicao na industria farmaceutica Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Finep.

Frenkel, J. (2002). Estudo da competitividade de cadeias integradas no Brasil: mpacto das zonas de livre comercio. Cadeia Farmaceutica, Ministerio do Desenvolvimento, Industria e Comercio Exterior, Brasilia.

Fuentes, A., & Pipkin, S. (2016). Self-discovery in the dark: the demand side of industrial policy in Latin America. Review of International Political Economy 23(1): 153–183.

Gereffi, G., & Evans, P. (1981). Transnational corporations, dependent development, and state policy in the semiperiphery: a comparison of Brazil and Mexico. Latin American Research Review 16(3): 31–64.

Gereffi, G. (1983). The Pharmaceutical Industry and Dependency in the Third World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Guennif, S., & Ramani, S. (2012). Explaining divergence in catching-up in pharma between India and Brazil using the NSI framework. Research Policy 41: 430–441.

Haque, I.U. (2007). Rethinking Industrial Policy. UNCTAD Discussion Paper No. 183 (UNCTAD/OSG/DP/2007/4).

Hollis, A. (2002). The importance of being first: evidence from Canadian generic pharmaceuticals. Health Economics 11(8): 723–734.

Filho, S.B. (2006). Pesquisa e desenvolvimento de fármacos no Brasil: estratégias de fomento. Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Ciencias Farmaceuticas.

Frost & Sullivan. (2004). Strategic Analysis of the Brazilian Pharmaceutical Markets. December 2, 2004. Accessed September 2013.

Lemos de Capanema, L., Palmeira, P., & Pieroni, J. (2008). Apoio do BNDES ao Complexo Industrial da Saúde: A Experiéncia do Profarma e seus Desdobramentos. BNDES Working Papers.

Lins Rodrigues, C. (2012). Políticas de Saúde, Desenvolvimento tecnológico e medicamentos: licoes do caso brasileiro. Campinas.

Lucchese, G. (2001). Globalizacao e regulacao sanitaria: os rumos da vigilancia sanitaria no Brasil. Fundacao Oswaldo Cruz.

Magalhaes, L., et al. (2003). Estrategias empresariais de crecimiento na industria farmaceutica Brasileira: investimentos, fusoes e aquisicoes, 1988–2002. IPEA Working Paper No. 995.

Mazzucato, M. (2013). The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. London: Anthem Press.

Mello e Silva. (1999). A generalizacao dificil – A vida breve da camara setorial do complexo quimico seguida do estudo de seus impactos em duas grandes empresas do ramo. São Paulo: Anna Blume/Fapesp.

Moretto, L. (2009). A era educacional do sindusfarma. São Paulo: Grafica Grecco Eds.

Ozawa, S., Evans, D., Bessias, S., Haynie, D., Yemeke, T., Laing, S., & Herrington, J. (2018). Prevalence and estimated economic burden of substandard and falsified medicines in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open 1(4): e181662–e181662.

Pacheco, M. (1983). Abusos das Multinacionais Farmacéuticas. Rio de Janeiro: Civilizacao Brasileira.

Pipkin, S., & Fuentes A. (2017). Spurred to upgrade: a review of triggers and consequences of industrial upgrading in the global value chain literature. World Development 98.

Piovesan, M. (2002). A construcao politica da Agencia Nacional de Vigilancia Sanitaria. Fundacao Oswaldo Cruz.

Prado, A. (2011). A indústria farmaceutica Brasileira a partir dos anos 1990: A lei dos genéricos e os impactos na dinamica competitiva. Leituras de Economía Política, Campinas 19: 111–145.

Quental, C., & Gadelha, C. (2008). Medicamentos genericos no Brasil: impactos das politicas publicas sobre a industria nacional. Ciencia e Saude Coletiva 13: 619–628.

Rodrik, D. (2015). Premature deindustrialization. Journal of Economic Growth 21(1).

Sabel, C., Fernandez Arias, E., Hausmann, R., Rodriguez Clare, A., & E. Stein. 2012. Export Pioneers in Latin America. Rochester, NY: SSRN.

Schneider, B. (2013). Hierarchical Capitalism in Latin America: Business, Labor, and the Challenges of Equitable Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shadlen, K., & Fonseca E.M. (2013). Health policy as industrial policy: Brazil in comparative perspective. Politics & Society 41(4): 561–587.

Souto, A. (2004). Saúde e Política: A vigilancia Sanitária no Brasil – 1976 a 1994. São Paulo: SOBRAVIME

Souto, A. (2007). Processo de Gestao na Agencia Nacional de Vigilancia Sanitaria-ANVISA. Instituto de Saúde Coletiva. Salvador: Universidade Federal da Bahía.

Souza, G. (2007). Trabalho em vigilância sanitária: o controle sanitário da produção de medicamentos no Brasil. Instituto de Saude Coletiva, Universidade Federal da Bahia.

Teodosio, R., & Camara, M. (1996). Abertura e competitividade no complexo químico Brasileiro: 1990–1995. Ciencias Sociais/Humanas, Londrina 17(3): 294–300.

Urias, E. (2009). A Industria Farmaceutica Brasileira: Um Processo de Co-Evolucao de Institucoes, Organizacoes Industriais, Ciencia E Tecnologia. Unicamp.

Vigilancia Sanitaria (2000). Inspection Results for Pharmaceutical Plants in the State of Sao Paulo in 1995 and 2000. Centro de Vigilancia Sanitaria CVS/SP Archives.

World Bank. (2017). World Development Report 2017: Governance and the Law. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Health Organization (2005). National policy on traditional medicine and regulation of herbal medicines. Geneva: 2005. Report of WHO global survey.