WAR FOR INDEPENDENCE, 1588–1620

Drill, training and supervision

William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg (1560–1620), portrayed in his early thirties. He was ‘the other stead-holder’: each province had its own lord steward, but at various dates during the war these functions were combined in the persons of fewer individuals: at first William Louis in Groningen and Friesland, Maurice in the other provinces. William Louis grew up and was educated with his cousin Maurice and brother John, with whom he worked to develop the new-model army. He was the author of a famous letter to Maurice in 1594 that first described and illustrated the infantry ‘caracole’ by ranks of shot. In the same letter he provided Maurice with Dutch translations of the drill commands he had found in a work by the early 2nd-century Graeco-Roman author Aelian. Maurice went on to use most of these, and translated them into several languages. (Anonymous, c. 1600; RM)

Finding their inspiration in the study of the classical authors, and finally commanding all the rebel forces, Maurice of Nassau and his cousins William Louis and John continued their search for an effective army. At each court new ideas were first tested on the table, with lead model soldiers, then tried out with real soldiers. The desire to emulate the classics, and to create structure where vagueness had ruled, resulted in the famous training manuals of De Gheyn and Van Breen. These manuals were only meant to train recruits to go through all the same necessary steps (De Gheyn mentions that he has left out all the ‘playful’ unnecessary additions). Even more important was the introduction of a fixed set of verbal commands for a fixed set of actions. By this means men could follow orders quickly, with everyone knowing what to do, where to go, at what pace, and what to expect. Commanders and troops could now give and follow orders without hesitation, automatically.

It took a while for the troops (and the onlookers) to get used to all this marching around, which was quickly dubbed ‘drillen’ (‘turning around in circles’). Commands consisted of two parts: the preparatory order, and the executive order. More than 400 years later some of the exact same commands are still in use in the Dutch army, for example ‘Rechtsom keert’ (‘About face’). On a ‘march’ command, soldiers had to step off with their left foot (right if moving backwards). The pace was set by the drummers, who could beat a slow march, a quick march, a charge or a retreat. Drill in unison, two-part commands, fixed pace and men starting with the same foot: all these combined meant a unit would manoeuvre in step, and everything should tick like clockwork. It was perhaps not explicitly realized then (and is still overlooked by the majority of historians) that drill also increases a unit’s morale and steadfastness, creating esprit de corps. These are exactly the qualities needed to field smaller, shallower and more isolated units successfully.

Less often illustrated than pikemen and musketeers, this is one of Maurice’s ‘targeteers’ (from ‘targe’, a round shield). Men armed with sword and buckler were quite common in most armies of the 16th century, to defend commanders and ensigns and to break into pike blocks, and in 1580 each Dutch company was to have six of them. He wears breast-and-back plates with faulds to protect the belly, and note the hook at his right hip (see also page 44). The buckler was shotproof, so heavy and eventually unpopular; ceremonial bucklers were much lighter, and Maurice kept them longest in the guard of his army. He also devised a special version to be used during sieges: it had a vision slit to allow peeping over parapets without getting shot. His own life was saved by one of these shields during the siege of Groningen in 1594, when the English commander Francis Vere had a similar experience. Commanders would specifically request them during sieges, as the Count of Solms did at Hulst in 1595. (Van Breen, 1618; RM)

Planned or not, Maurice took full advantage of these new attributes. The new drill and organization meant that he could field three tactical units with the same number of men that his opponents concentrated in one. The troops had to practise all the time, even during the winter and on the march. This included firing practice; for example, at least once a fortnight groups of 20 to 30 men had to fire a minimum of four shots at man-shaped targets (muskets at a greater distance than calivers). Once a year every ten to 15 groups would compete for prizes (and punishment for those who still made basic errors, like failing to hit the target, or walking around dangerously with the barrel not pointing upwards). Officers had to study for tests too, requiring perfect scores; examples of these tests might be ‘First question: 20,000 foot and 5,000 horse – How much does it cost to pay them for one month?’; or ‘How many hours does it take them to throw up a rampart around their camp?’

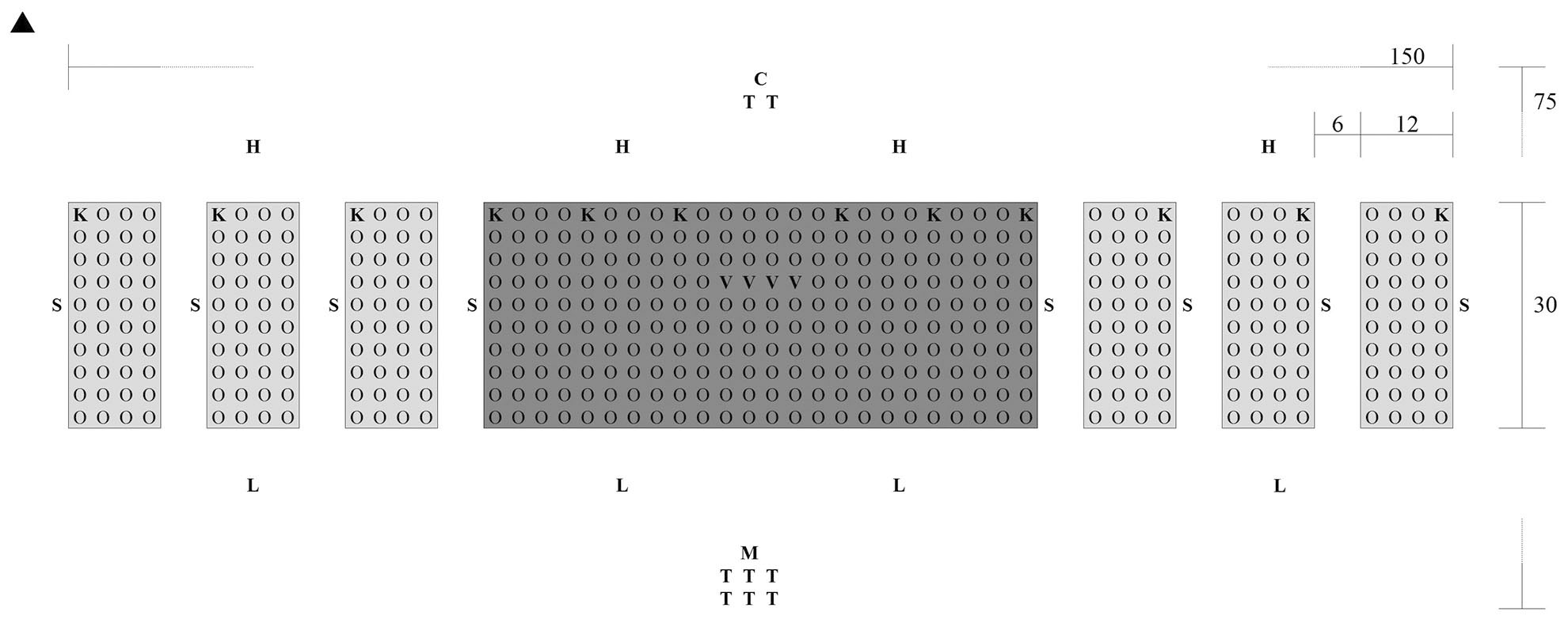

Formation of a 500-man division of four companies, in ten ranks; dimensions at right are in feet; dark shading = pike, pale shading = shot.

(Key:) C = colonel, H = captains, K = corporals, S = sergeants, V = ensigns with flags, L = lieutenants, T = drummers; M = second-in-command, usually lieutenant-colonel or sergeant-major, who would command a division if their regiment provided more than one. The division’s commander and the captains would always be closest to the enemy, the lieutenants and second-in-command the furthest; officer seniority was from right to left. Each corporal was supported by a lance-corporal in the rear rank of his file. Any calivermen, as distinct from musketeers, would form the outermost files of the shot. In Maurice’s time the first two ranks of pikemen were more heavily armoured than the other ranks. The drummers shown at the front would only be there if the division was operating alone. (Author’s drawing)

At some time during the early 1590s regimental and army exercises were added, even wargames between opposing ‘armies’. This allowed commanders to gain experience and men to get used to large-scale manoeuvres. Army exercises had another advantage: the preliminary inspections enabled the government to discover fraud more easily. It was hard enough to ensure that enough money was available to pay the whole army, and trickier to determine whether each company received pay for its real strength and not the usually higher ‘paper strength’. After one such early surprise roll-call near Zelhem during a march to Grol (Groenlo) in July 1595, 1,000 absent men were struck off the payroll. Such precautions, together with regular payment (every seven, later every six weeks), and year-round employment, made sure that companies stayed much closer to their paper strength and that experience was preserved. During the early days William Louis tested most new ideas on the Friesland Regiment, which became the best-drilled and most up-to-date corps. Maurice was hesitant to risk it in open battle until the rest of his standing army had caught up, by 1597.

In a matter of a few years, all the plans and ideas had been tested and distilled into a set of most effective commands, drills and formations, which went on to deliver victory at Nieuwpoort (1600).

Organization

William’s drive to reorganize and standardize continued under Maurice, to be finalized as state resolutions. As if to underline the reforms, the men now started to be called ‘soldier’ (soldaat), instead of the earlier ‘servant’ (knecht). As before, a company’s cadre of officers consisted of a captain, two lieutenants, two sergeants, three corporals, two drummers, and – left in camp – a quartermaster and a barber-surgeon. Companies with more than 150 men also had a fifer, exchanged for a provost in 1599; so-called double companies – usually colonel’s companies, and not always actually twice as big – had an extra sergeant. Besides these officers, a 150-strong company in 1589 had 39 pikemen (always the tallest men in the unit), ten halberdiers, three sword-and-buckler men/cadets, 30 musketeers, 52 calivermen, and three boys. Accepting the realities of life in the field, one of the soldiers would be appointed as a sutler. New recruits were trained by the corporals, and the eldest cadet was responsible for the company’s arms and armour.

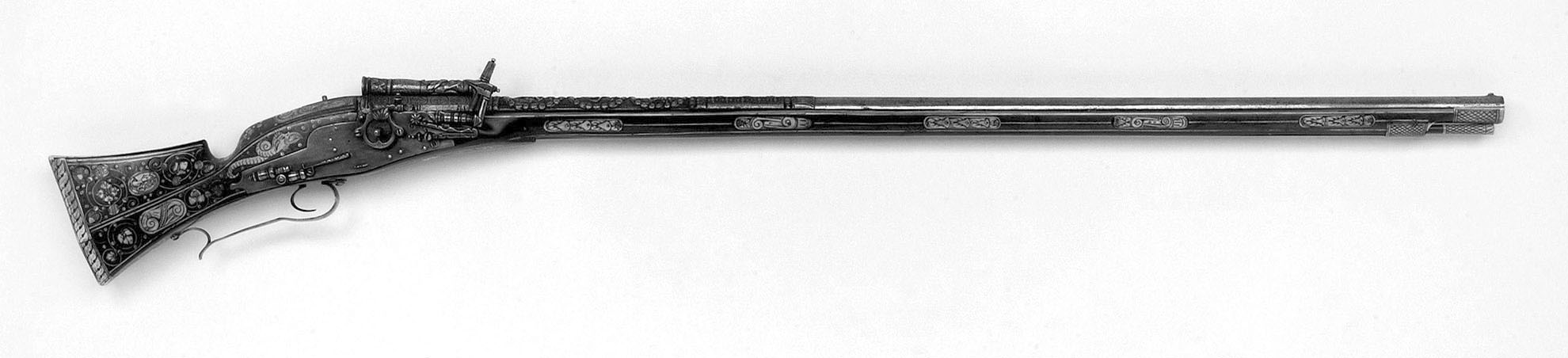

Expensively inlaid private-purchase firearms of the early 17th century; while mechanically identical, normal issue muskets would not be decorated in this way.

Matchlock musket, early 1600s, about 5ft 3ins long (160cm).

Within a decade halberdiers had disappeared from the regulations, and by 1597 companies had been equally divided between pike and shot. Twelve years later the caliver was finally stricken from the official organization and started to be phased out. Many captains had preferred muskets over calivers long before that, but they were forced to employ them, perhaps because the caliver’s lighter weight and higher rate of fire made it better suited to operate on the flanks. Alongside the calivermen, most sword-and-buckler men also disappeared, although the bodyguards of dukes and princes might still be equipped with halberd or sword-and-buckler. (In 1596 the government suggested in vain that companies should be equipped with only a single type of weapon, retaining several mixed companies for garrison duties alone.) When calivers disappeared, a company’s firearm-to-pike ratio also changed. From 1600 or so the ideal company had equal numbers of pikes, muskets and calivers, and when calivers disappeared the pike ratio in the company climbed from one-third to half, perhaps to better counter horse. In the early 1620s this ratio was made official.

Wheellock from around 1625, 5ft long (150cm). These and snaphaunces were expressly forbidden among the rank-and-file of the shot, though individual officers might own such expensive weapons. Note the long trigger guard, reminiscent of the old bar-trigger of the previous century.

Matchlock musket of around 1625, just over 5ft long (154cm). (All photos RM)

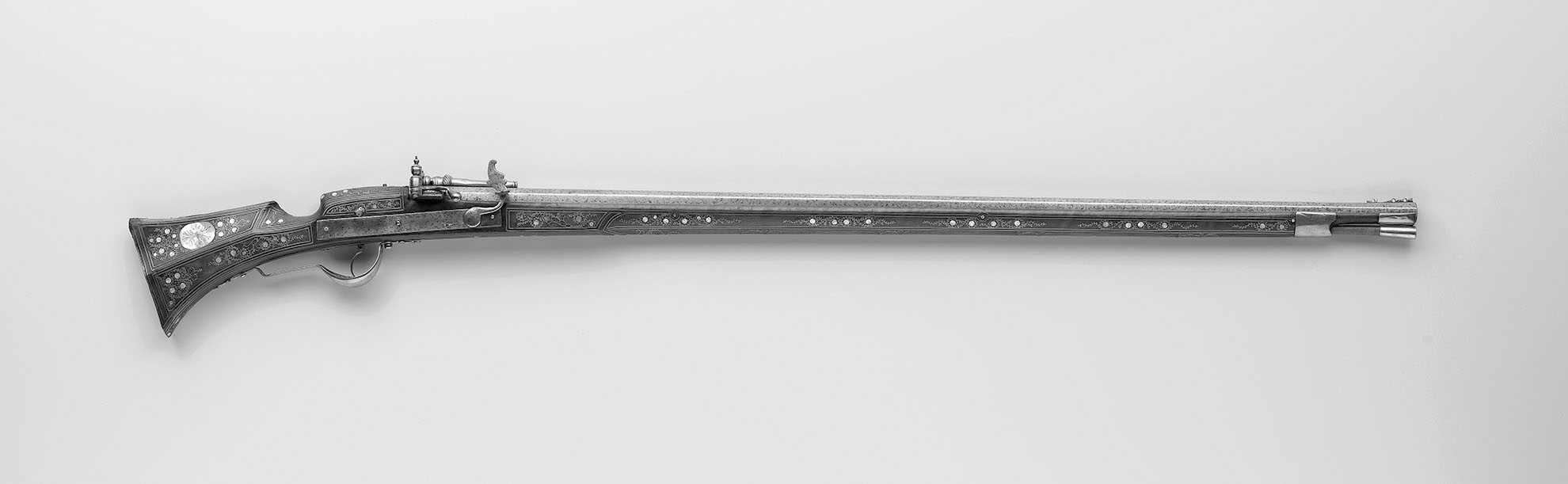

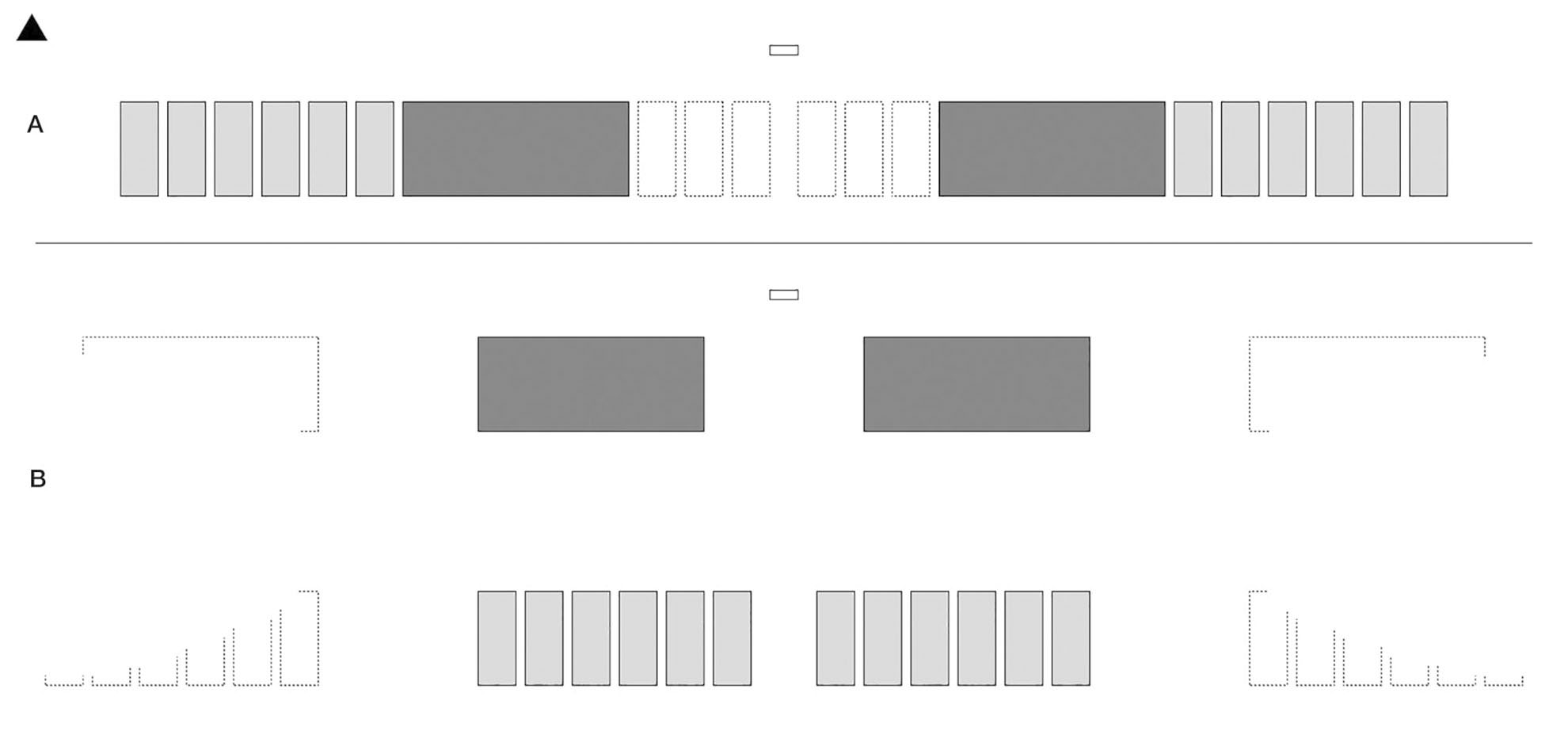

A 1,000-man pair of divisions, in (A) the earlier wide formation, 450ft wide (137m), and (B) the later deep formation, only 200ft wide (60m). Dark shading = pikes, pale shading = muskets, white = vacated positions.

(A) Half the musketeers of each division, originally in the central gap, have moved out left and right to join those on the outside flank of their own pike block; however, at this date the pike blocks maintain the 100ft (30m) central gap, which was vunerable.

(B) This shows how Maurice solved the wide formation’s weakness against cavalry, by concentrating the muskets behind the pike blocks, and closing the central gap to 50ft (15m). This allowed higher densities of men in both pike and musket units, and the musketeers were better protected by the pikes.

The formation’s leader, usually a colonel, would be on horseback and have several drummers with him (small block at front centre), and – if this formation comprised the whole regiment – the regimental banner or colonel’s ensign. (Author’s drawing)

Regiments still did not have a fixed number of companies, but they did become administrative entities of their own, with their own colonel and a colonel’s company. This latter was often larger and usually included quite a number of young noblemen, volunteering for a year or so to learn the trade while usually serving as ordinary pikemen. Regimental staff consisted of a lieutenant-colonel, a sergeant-major (who outranked captains), a drum major, and – left in camp – a quartermaster and a provost; a chaplain might also be present. During a campaign a government-appointed commissioner joined the regiment, to sniff out fraud and to keep a steady flow of recruits coming to make up for any losses. John van Oldenbarneveldt (1547–1619) was the country’s ‘grand pensionary’, roughly comparable to a prime minister. It was he who ensured that the necessary bureaucracy ran smoothly, maintaining financial and political stability. In June 1604 Maurice explained to the government that an army could never be in the field longer than three to five months without losing up to a third of its number to disease and battle casualties.

Beyond regiments there were no fixed groupings, but John of Nassau-Siegen notes that in an army the ratio of foot to horse should be three to one. There were higher ranks than colonel, of course, up to the captain-general or commander-in-chief. Several deputies would always travel with each army, to report back to the government on a daily basis. In 1596 it was decided to increase the standing army to 12,000 men. This included the first foreign regiments in permanent service: one English (Francis Vere), one Scottish (Alexander Murray), one German to be formed from all the Germans in other companies (in 1599 under Ernst Casimir), and one new French regiment (in 1599 under Odet de la Noue). No doubt drilling became more effective once soldiers were put together according to their mother tongue: command leaflets were printed in Dutch, English, French, German and Scottish. When Maurice took over in 1588 the whole army had 129 foot companies or 19,000 men. In 1600 it counted 264 foot companies, or 35,000 men. By 1607 that had increased to 353 foot companies, or 55,000 men.

In the field

Maurice fielded three tactical units for the ‘manpower price’ of one former unit. Maximizing the use of his expensive manpower, he made units shallower: ten ranks was the new norm, not the 30 ranks still common elsewhere in the early 1600s. He formed the men from the inactive rear ranks into new units, extending the line. A 1584 pamphlet stated that a unit would anyway collapse in rout after it had lost its front three to four ranks; indeed, the first experiments were done with five ranks only, and in his notes John of Nassau-Siegen mentions that the only reason to add another four or five ranks is because ‘you have plenty of people’.

During deployment ranks were 6–7ft (180–210cm) apart and files either 3ft (90cm) or 6–7ft. During battle, ranks and files would close up to 3ft intervals. If things got really bad, pikemen would close both ranks and files up to only 18ins (45cm), but then they would not be able to turn. These distances were measured by holding out arms or weapons. Each man had a fixed position in the formation, so no matter the disorder the unit could quickly reform. On the battlefield, several companies were now combined to create – ideally – a 500-strong division, initially called a ‘troop’ ; the surplus men too few to make an extra file were posted behind it. A division would deploy in the traditional way of a block of pikes (with its banners in the centre) with – at around 10ft (3m) distance – two flanks (‘sleeves’) of firearms, with the muskets closest in and the calivers on the outside.

For battle, two divisions would be deployed next to each other in a pair. The shot between the two pike blocks would then move out to join those on the outside flanks, but initially the pike blocks would keep their original interval of about 100ft (30m). Two or more division-pairs would form a brigade, with any unpaired division left acting as a reserve. During the march, units would split into (usually) four parts: firearms at front and rear, both pike parts in the middle, each of the same width and always ten ranks deep. If a column of march was formed by a single company, each of these parts might have anything from two to seven files; if it was a larger formation, then each part might be up to 50 files. On the field these four parts would form up to the left: i.e. the first halted, then the others lined up on its left side, forming a division or pair of divisions. Because each part was always the depth required for battle, they could quickly deploy into battle formation.

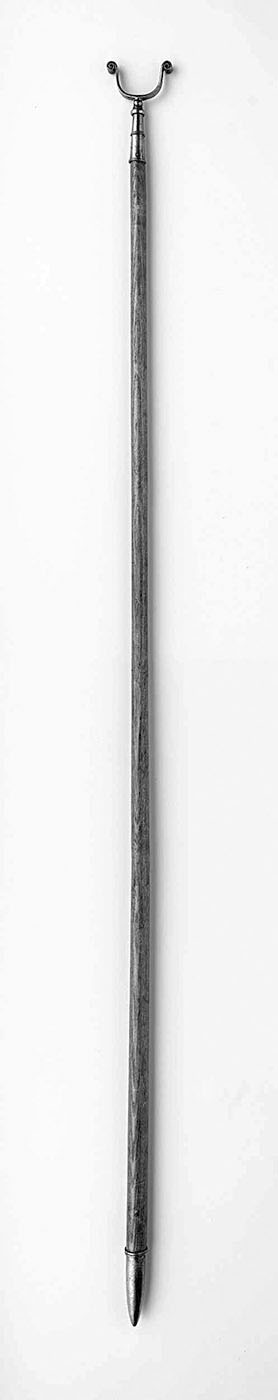

Musket rest, first half of the 17th century, 5ft (150cm) long. (RM)

Three brigades formed an army, being called respectively the ‘advance guard’, the ‘battle’ and the ‘rearguard’. On the march, brigades took turns marching at the head, as did the divisions within each brigade. On the battlefield, each brigade would form one line, so the army deployed in three supporting lines, with divisions or division-pairs in a chequerboard formation. Experienced commanders could and would adapt to particular situations. For example, in 1602 during the siege of Ostend, Francis Vere ordered his men, defending a wide breach against a 2,000-strong Italian assault, to fall and lie prone just as the enemy was about to shoot. After the Italian volley Vere’s men quickly rose up, unharmed, to fight off the attackers.

John of Nassau-Siegen also had some non-regulation ideas. A general should ride a horse, never go in front of his units, and never join a unit, otherwise he would lose his overview of the whole. When a mêlée was inevitable, two ranks of musketeers should be put in front of the pikemen. These should hold their fire until the opponents charged, and after their volley they should either kneel under or retire through the pikes. Other important tips in John’s notes are that it is always best to attack slowly and purposefully, and that units should never change direction during an attack.

Sometime after Nieuwpoort, Maurice made two important changes to improve the army’s steadfastness and flexibility. Brigades would now deploy from right to left, so the first one to arrive on the field would take up a position with its division-pairs one behind the other, then the next brigade would march to extend these three lines to the left, and so on. This improved command and control, and immediately created depth the better to counter cavalry. Scaling this down, divisions and thus division-pairs likewise changed from wide to deep formation. The muskets were now posted 50ft (15m) behind their pikes, with ranks marching out to the sides to shoot in turn between the blocks. This allowed the two pike blocks to stand closer together, also around 50ft. Maurice designed this formation to overcome the shallower infantry formation’s weakness against cavalry. According to his half-brother John, musketeers could now feel safe behind their pikes and focus more on their job (which was, according to John, to shoot at pikemen and officers, not musketeers). Moreover, the pikemen would no longer be disordered by musketeers running for cover during a cavalry charge (which cost the Spanish dearly at Nieuwpoort and Xanten); and the two pike blocks now stood close enough together to discourage enemy horse from advancing through the gap – if they tried, they would soon receive a deadly fire in both flanks, instead of riding down fleeing musketeers.

Musketeer’s bandoleer with ‘the 12 apostles’ and a bullet-bag, first half of the 17th century. (RM)

Another big advantage of the new method was that divisions and division-pairs could now be grouped in threes, without the need to adapt a division’s individual deployment to the situation (as was still necessary at Nieuwpoort). This turned the previously ‘odd-man-out’ division extra to a division-pair into an integral part of a deployment, with brigades often formed up as a wedge (see diagram on page 35). Within the same brigade, divisions would be deployed 50ft (15m) apart, or with a gap still wide enough to allow a division to march through. Brigades would be 200–300ft (60–90m) apart laterally; the first line was 200–300ft in front of the second line, the third line 400–600ft (120–180m) behind it. All these numbers and formations were personally penned by the men at the top of the chain of command, such as Frederick Henry and Simon Stevin.

Maurice practised and showed off these deployments – and the speed with which his drilled army could achieve them – at every opportunity when an enemy army was near enough to be discouraged by the sight (e.g. Gulik, Rees).

Combat drill

Maurice drilled his men not only to deploy in certain formations, but also to fight as a single entity, on command, without losing control. His units could thus continue to fire with the same efficiency as in the first volley. William Louis pointed out that a big problem of the old system was that units lost cohesion because calivermen would fan out in a screen, shooting from behind any kind of cover.

John’s notes explain the drill in great detail. First for the pikemen: when cavalry were near they should close up, the first five ranks lowering their pikes with the butt against their foot. If fighting foot, they should hold their pikes horizontally and advance forcefully. When threatened on several sides, the five files on each side should turn to face the threat and lower their pikes.

John’s notes on firearms are more extensive, and show the many modes of fire that the United Provinces’ foot had mastered. In small units, if the men had to pass through their unit they would simply walk between the files. In larger units, e.g. a division, each firearms ‘sleeve’ would be divided into three or four sub-groups each led by a corporal. Each of these would close up their files to their flank file, forming pathways no wider than 6–7ft (180–210cm) wide between each sub-group. Now, if the men had to pass through their unit, each rank of each sub-group would file along these pathways, thus increasing the speed and decreasing the chance of disorder. Forming these sub-groups was usually done immediately after the first volley by the front rank. In a deep division-pair, files would close up into the gap between the divisions.

(1) Skirmishing. One or all files of a sub-group would advance about ten paces in front of the unit, angling towards its centreline. At the designated spot, the front man/rank would fire, turn and fall back past the others. The next would then step up, and so on. The cycle could repeat, or move along the line, and could be executed on several sides. This looping around was identical to the procedure used for firing practice (the ‘kranendans’ or crane dance). This skirmishing by sub-group was the precursor of later platoon fire, in which the whole sub-group fired as one instead of rank by rank.

(2) Skirmishing Advance, either by rank or by file. If by file, the outermost file halts, quarter-turns and fires, while the next file starts the same cycle. After that next file fires, the first file moves adjacent to it; the two then do the same with the next pair, until all files are back in formation. If by rank, the front rank would wheel, then after firing each man would start to walk back the moment the unit had advanced past him.

(3) By Rank. When advancing, the next rank would pass the one that had just fired. When halting or in melée, each man would walk back through the formation, while his file moved up one position. A stationary unit could similarly fire to one or both flanks, using ranks as files. If cover was present, the ranks would ‘cycle’ up to it, then back again. If the unit was retreating – facing away from the enemy – the rear rank would halt, quarter-turn, shoot, then pass through the unit to become the new front rank.

(4) By Unit. The unit would halt, the firearms would open files to 6–7ft and fire along the lanes between files, either by rank in quick succession starting with the rear rank, or all men together. In case of a threat from flank or rear, the men would first turn to face it and then open ranks to create the firing lanes. If threatened on several sides, the five files on each side would do so.

(5) Square. The firearms take shelter under the pikes, except for the best among them, who take up positions in the unprotected corners, holding their fire until the very last moment.

The soldiers’ equipment

There were no regulations regarding uniforms, but the province usually supplied units with their clothes, often referring to unmentioned colours and patterns. Units recruited together could be expected to look the same. Again, blue is the colour most often mentioned in government papers. These also show that English troops invariable arrived dressed in red, while in 1598 Swiss troops still wore their traditional outfits. Plumes continued to be popular, orange-and-white being the most frequently seen. Officers, especially the higher ranks, usually wore orange sashes around waist or right shoulder. Extra money was reserved to purchase clothes for fifers and drummers, and a banner for each company. Guard companies would look fancier – more elaborate collars, and the like.

Maurice experimented with even bigger shields than shotproof bucklers. These swordsmen wore similar helmets and half-armour to the mounted pistoleers (reiters), and note that this man also has greaves to protect his shins. While they proved effective in mock fights against trained pike units in 1595, such soldiers were only deployed in Maurice’s guard , and probably not for long: their heavy shotproof armour and ‘Roman’ shields must have quickly exhausted them in combat. Shields like this were made in The Hague until the late 1610s, but only of wood and leather, for ceremonial purposes. Maurice also experimented with pike-and-buckler men, but they too were not seen outside his ‘laboratory’. (Van Breen, 1618; RM)

Arms and armour were increasingly supplied from central stores, purchased nationally and internationally. Armour was blackened. The 1599 resolution states that pikemen were to be equipped with a sword, a gorget, a breast-and-back plate, a pike of at least 18ft (6m), and a helmet. One in four also had to have arm and leg protection, i.e. pauldrons fastened to their gorget and tassets to their breast plate.

Calivermen were now required to wear a helmet. Each was to have a sword, and a caliver with a bore of 20 bullets to the pound, but actually shooting balls weighing only 24 to the pound (lighter than several years earlier), which were able to wound at 600ft (180m). Wheellocks and snaphaunces (see below, ‘Coalition War/ The soldiers’ equipment’) were expressly forbidden. Musketeers also had a sword and a helmet, plus a rest, and a musket with a bore of ten bullets to the pound, but shooting balls at 12 to the pound; from a 4-ft (120cm) barrel, these could wound at 800ft (240m). Not mentioned but of course expected were powder and/or priming flasks, bandoleers, etc., as described above.

Any halberdiers and sword-and-buckler men still present would have been equipped like pikemen. Stiff fines were meted out for not wearing regulation armour, or for shortening pike or musket – all popular methods of lightening the load. Until about 1615 bucklers continued to be made in Holland in small numbers, but were no longer shotproof. In the 1590s Maurice had experimented with larger than normal numbers of bucklers, for both swordsmen and pikemen, and even with Roman-inspired rectangular shields carried by even more heavily armoured men. Although these last proved very effective for men breaking into pike blocks – as witnessed during 1595 army exercises – they only saw service for a short while in Maurice’s own guard. The general culture was one of simplification and standardization: eventually, only pikes and muskets would survive.

One last piece of equipment, and yet another way to protect the foot against enemy horse, was the cheval-de-frise, (interconnected) 6ft-long poles (180cm) with a metal spike, deployed in front of the firearms men. Though not always present, an army would certainly take them along for the initial phase of a siege, to use before ramparts were ready.