HOME-DEFENCE & EXTERNAL OPERATIONS

Civic guards

Cities had had their own burgher guards since medieval times, and many retained their old names throughout the war. Each unit was the size of a ‘corporalship’, perhaps 30 men. Later the bigger cities reorganized them on the basis of numbered districts. During the first decade of civil war they played an active part; with the power to open or close the gates to approaching rebels or royalists, they often decided which side the town would join. They saw little action except during sieges.

John VII, Count of Nassau-Siegen (1561–1623), at the age of 54; in 1601–02 he had served as a field marshal in the army of the States’ Protestant ally Sweden in its war against Poland. Raised with his brother William Louis and cousin Maurice, he too played an important role in the army reforms. Invaluably for historians, his many writings are still preserved; they include manuals, and a kind of flow-diagram for every level of command and every situation. Between 1596 and 1598 it was John who commissioned De Gheyn to make the plates illustrating the individual arms drills, and he founded the military college led by John Jacob von Walhausen (1580–1627). (Van de Passe, 1615; RM)

Besides the volunteer civic guard, from at least the 1570s there were paid militias (‘waardgelders’). Most were organized by individual cities, recruited from among the poorest inhabitants. They were called up for a single campaign, to replace the garrisons of large frontier cities in Holland so that those professional soldiers could join the field army. In 1623, for example, 6,000 were recruited. They were not allowed to serve in their own city, however: e.g. in 1622 the Amsterdam militia had to go to Zwolle, and the Leiden militia to Grave. Individual garrisons might be as big as 40 companies, and in some cities one in every four men was a soldier. Paid militia were organized like the regular army, but without the camp officers. Every 12 days each company had to be drilled, and every two months as many companies as could be assembled had to exercise together. Their equipment followed the regulations for professionals. During the last decades the gorget seems to have become a sign of rank for militia and civic guard officers, who adopted buff coats in preference to plate corselets and tassets.

Fighting for allies

The foot troops of the States’ Army did not only march into battle on home soil, nor did they comprise the whole infantry of the United Provinces. The Dutch received contributions of money and troops from other countries throughout the war against Spain, and they likewise supported their allies. At the start of the conflict Huguenots rode to the aid of the Nassau brothers, and the brothers marched to help them in France (e.g. Moncontour, 1569).

After the whole country rose in revolt, France and England each sent contingents. By 1600 most of these had been absorbed into the national army as English and French regiments. Returning the favour, nine Dutch companies joined Drake’s and Norris’s failed expedition to Corunna and Lisbon in April–June 1589 (the ‘English Armada’). In 1599 some of the English regiments were sent back to England on two occasions, each time numbering around 2,000 men. In 1592 the French king was supported at Dieppe by 20 Dutch companies, including the guard companies. Two years later 22 foot companies and five cornets (cavalry squadrons) were sent overland to assist France against Spain, joined on the march by another 16 foot companies and four cornets. In 1595 three Dutch regiments were sent, and the United Provinces funded 3,000 new recruits in France; an extra 15 companies, led by Maurice himself, also briefly entered the fray at Calais. The following year another new regiment was financed.

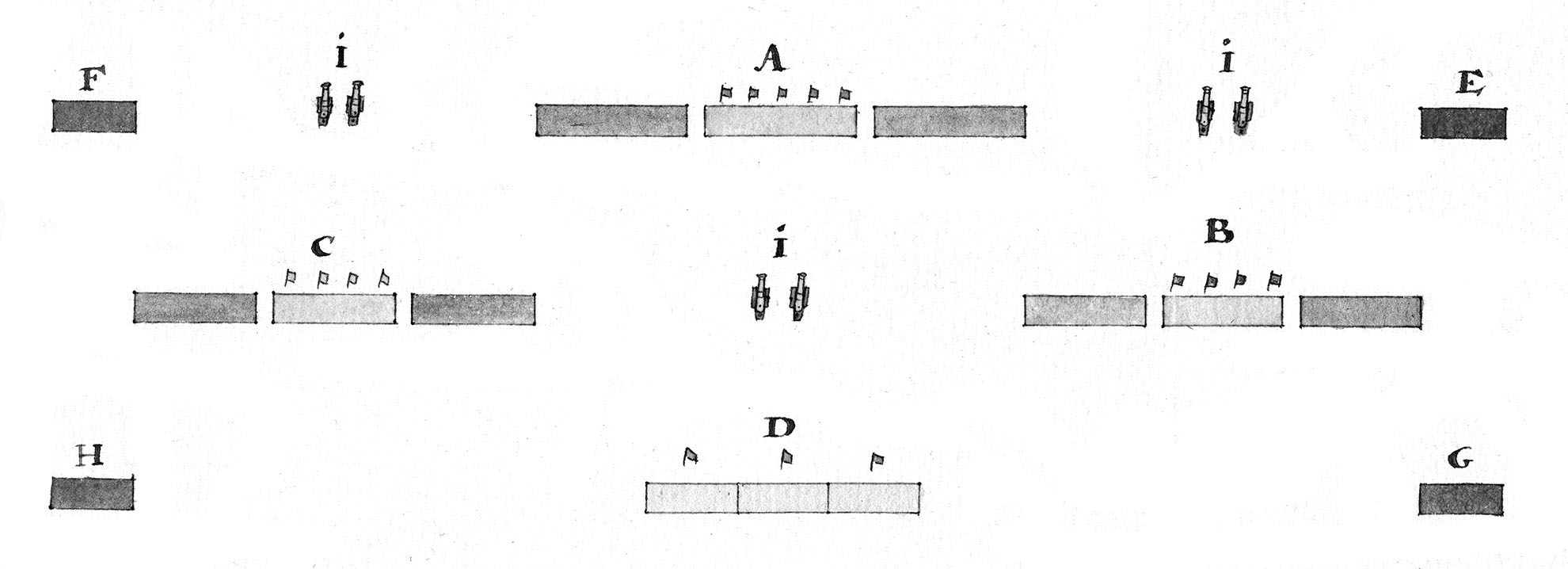

Battle order for the expedition to take Luanda in Angola from Portugal in 1641; the force sailed from Brazil. Depicted are three wide divisions of pike and shot (A, B and C) totalling 13 companies; three companies of ‘Brazilians’ (D); six guns (i); and, at the corners, four flintlock companies (E, F, G and H), no doubt forming the skirmish screen. (Detail of the 1641 original: KV A04b-1454-148)

Protestant forces in Germany were supported with money, equipment and recruits, but also with interventions. In 1615 Frederick Henry took a peace-keeping force of the nation’s entire horse and many musketeers to put an end to a conflict in Brunswick, and his imminent arrival quickly convinced the opponents to cease hostilities. In 1620 Frederick Henry marched into Germany again, now commanding 35 Dutch cornets and five guns, as well as 2,200 newly recruited English foot carried on 200 carts. He was supposed to join an army raised by Protestant princes, numbering around 12,000 foot and 4,000 horse, south of Frankfurt am Main. The princes had agreed that he would then take general command and seek out battle; however, when he arrived they refused to hand over their individual commands. The whole army remained passive, and the Dutch contingent returned home later that year.

The United Provinces also supported Venice in its war against the Pope and thus the Catholic League; from 1606 arms and training officers were sent, and in 1617 three specially recruited regiments arrived in Venice. These first participated in the siege of Gradisca, then served as marines in the Venetian fleet. A year later another regiment arrived, all veterans who had served under Maurice. The Dutch troops stayed until 1620.

Brazil and Angola

Economic advantage was an important war aim, and such gains could be achieved in faraway places that also needed protection, as far afield as South America and south-west Africa.

From the early 1600s Dutch merchants organized their seagoing enterprises into big share-holding companies, chief among them the West Indies Company (WIC) and United East Indies Company (VOC). If possible, local alliances were made, but the companies still needed land-based military forces to protect their trade interests and carve out monopolies. Most men were recruited in Europe, and sometimes these were used by the States’ national army before being shipped overseas, as happened in 1629. The VOC army would grow into a large but scattered force, engaged all over Asia, but the biggest overseas army during this period was maintained by the WIC.

In New Amsterdam (today’s New York) several small ‘wars’ were fought, but the majority of the manpower went to Brazil, where rivalry with Portugal (then in dynastic union with Spain) broke out into full-blown warfare in the first half of the 1620s, and again in 1630–41. In Brazil the Dutch made allies among local Indian tribes who rose against Portuguese rule, and these contributed large contingents to several battles (e.g. San Salvador de Bahia). A number of Indians were brought to Holland to learn the language so they could act as interpreters. Others sailed to Europe to be soldiers, serving as scouts in the States’ field army; the last one retired some time around 1660. Many local Indians were recruited into the WIC army in Brazil, where they served alongside Europeans and mulattos (men of mixed race) as skirmishers. There were a few major clashes in Brazil (e.g. Porto Calvo and Guararapes, both twice), but most warfare was a guerrilla affair of exhausting patrols, long-distance raids and vicious ambushes. These men operated in small units and had to carry and haul along their own provisions. In 1631 the WIC army in Brazil counted 36 companies. The last force recruited to serve there was all of 6,000 strong, armed entirely with firearms; the first half arrived in 1648, the rest a year later, when the Portuguese victory in the second battle of Guararapes proved decisive.

These conflicts spilled across the South Atlantic to Angola, which was the origin of most of Portugal’s slaves for their Brazilian sugar plantations. By 1624 an alliance had been concluded with a Congolese king to overthrow the Portuguese in Angola. In 1641, 20 companies and six guns landed to take Luanda, and after its capture 1,500 men were stationed there. These took part in several inland expeditions together with Congolese forces (e.g. Namboa Angongo and Kombi).

Throughout the period Europeans were dressed and equipped as per regulation, though it is not known whether the pikemen carried their full armour; musketeers seem to have left their helmets at home, preferring hats. Mulattos and other locals wore local clothes and used the same European weapons, but do not seem to have been employed as pikemen. The Indians’ primary weapon was the bow and arrows; at home they went naked, but in the army they wore a simple loincloth. By 1640 flintlock-equipped companies had become an integral part of the WIC’s Brazilian army, and four flintlock companies took part in the Luanda expedition in Angola. In 1648 the army received 1,000 flintlocks, shooting bullets of 20 to the pound from a 3½ft-long (105cm) barrel; the flintlock was, of course, much better suited to patrols and raids than the heavier matchlock. These men probably also carried a 6–8ft spear (180–240cm) instead of a sword, and had a cartridge bag instead of ‘the 12 apostles’. Their companies had trumpeters instead of drummers, underlining their primary use as skirmishers.