People Associated with the Discovery and Visual Representation of Birds of Paradise

This appendix is somewhat arbitrary and by no means comprehensive, and not all of the people mentioned in the book are listed. Where a portrait of an individual has been found, it is included. The size at which such images are reproduced – or even their inclusion – is not intended as a reflection of a person’s importance in the story of the birds of paradise.

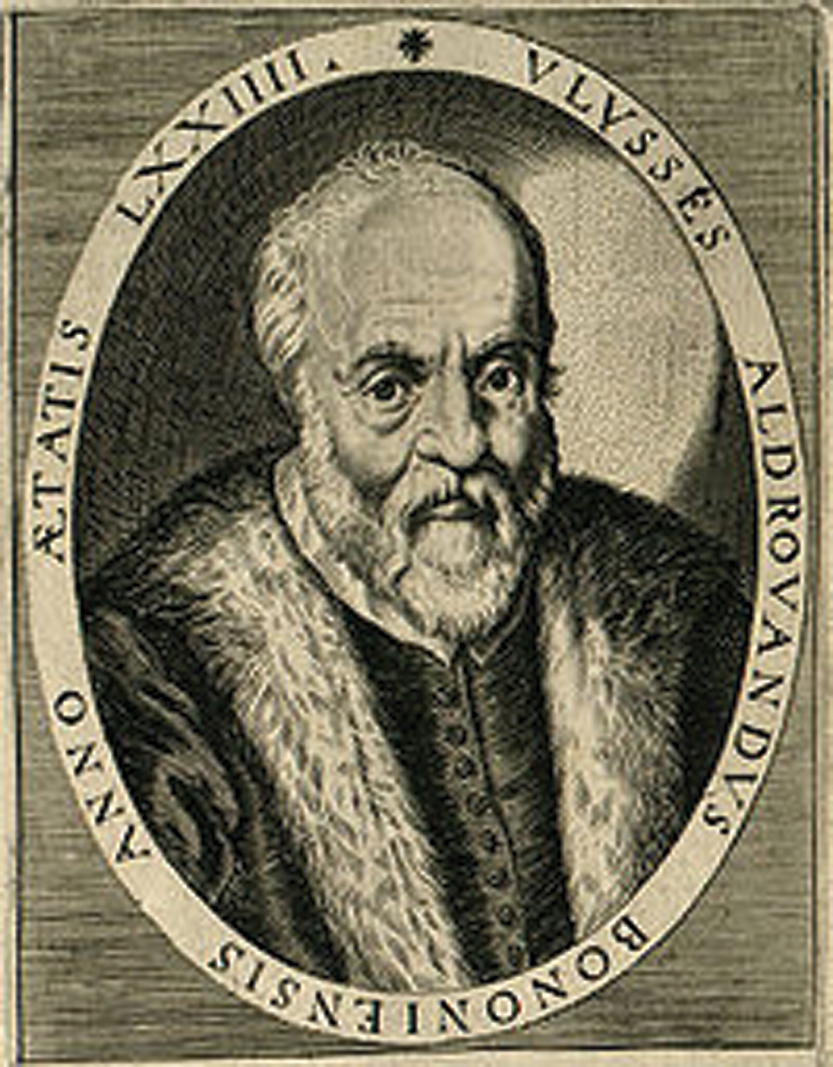

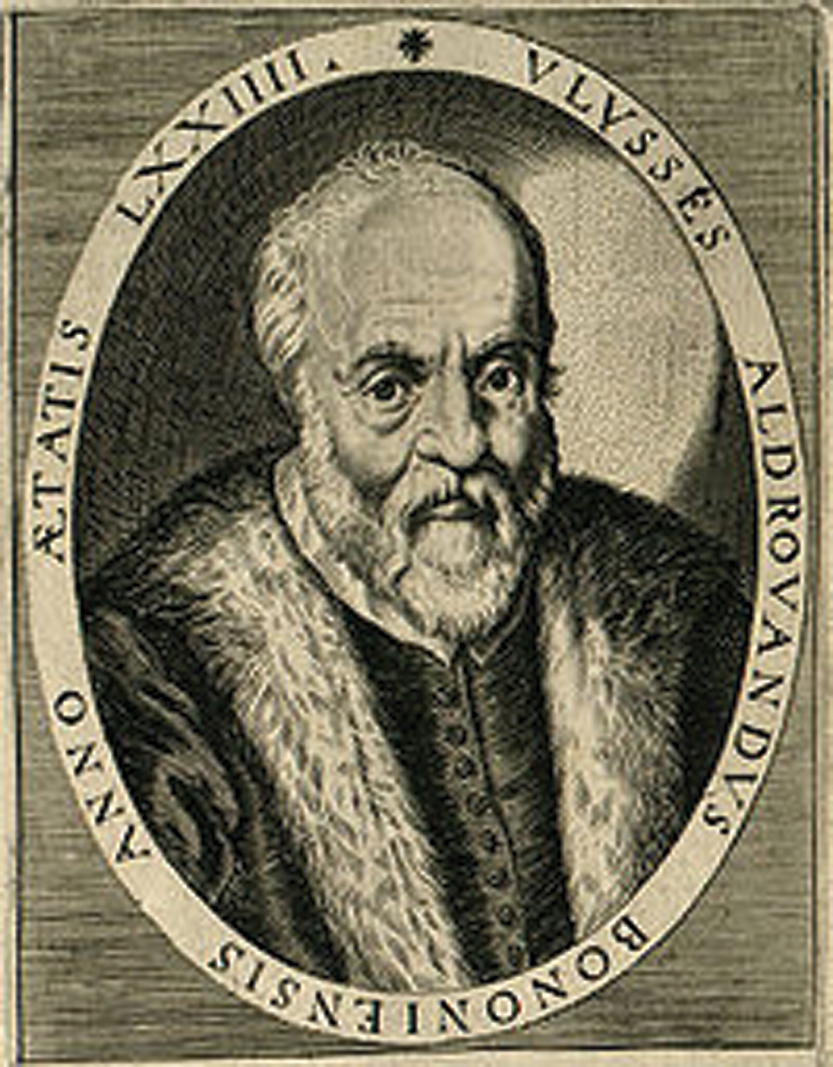

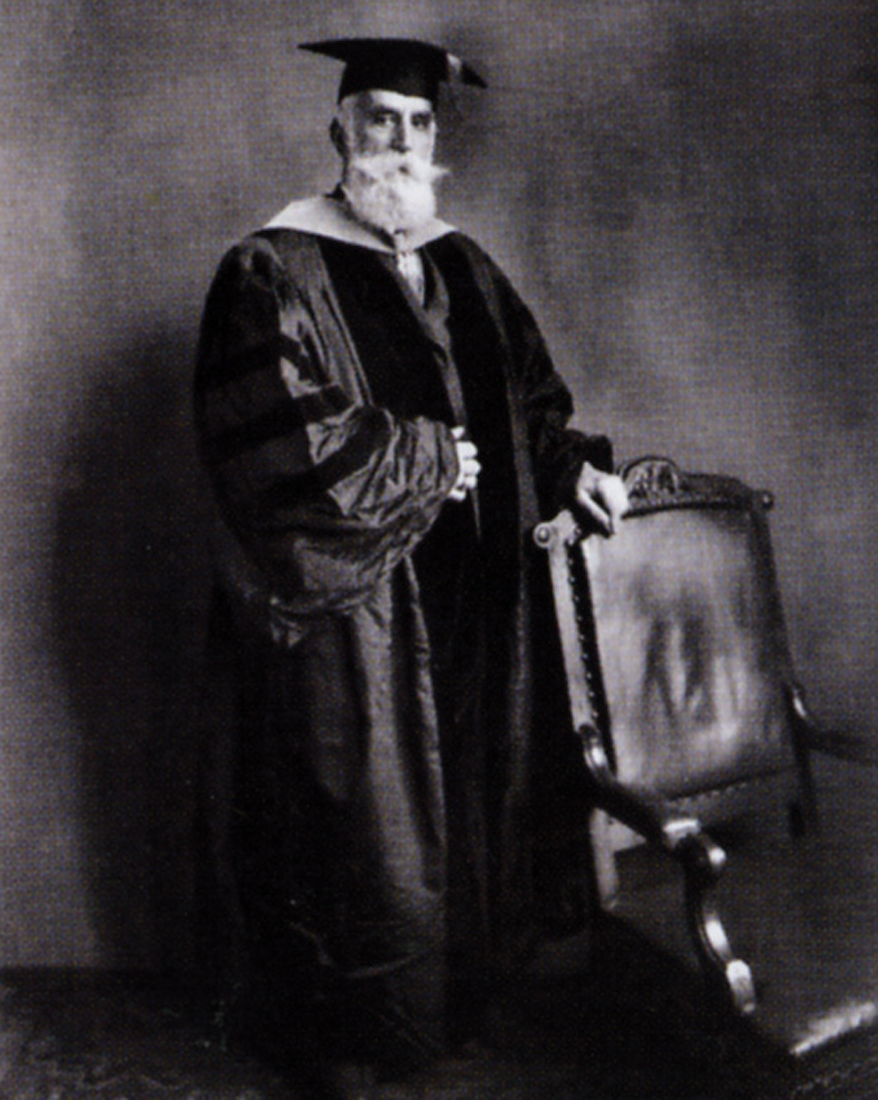

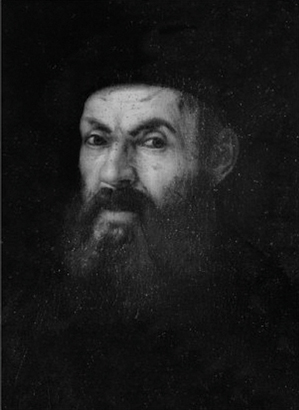

Ulysses Aldrovandus (1522–1605). Although he was professor of medicine at the University of Bologna, Aldrovandus was deeply interested in all aspects of the natural world and throughout his long life he collected specimens of everything he could find. Eventually, his collection was said to fill over 4,000 drawers. In 1599, at the age of 77, he started to publish accounts and illustrations of the specimens he possessed – and many, including dragons and mermaids, that he did not. Much of his information was based on a previous work written by a Swiss scholar, Conrad Gesner (1516–65). But whereas Gesner had arranged his entries alphabetically, Aldrovandus recognised the relationships between animals and grouped them, more scientifically, in families. He died in 1605 with only three volumes of his work, The Ornithologiae, completed. His pupils, however, continued his work, at first using his notes and then compiling the information themselves. The last of the 13 volumes of this great encyclopaedia appeared in 1667 over 60 years after its founder’s death.

Jacques Barraband (1761–1809). Despite the incredible beauty of his images, and the great influence they have had, comparatively little is known of Jacques Barraband, and it has not proved possible to find a portrait of him. He was the son of a weaver, and it seems that he worked originally as a tapestry designer at Gobelin’s, and later turned his hand to decorating porcelain at the famous factory in Sèvres. In his late twenties he came to the attention of François Levaillant who commissioned him to paint watercolours (to be used as the basis for engravings from which book illustrations were produced) of birds – mostly toucans, parrots, cotingas, rollers and birds of paradise. These watercolours stand among the finest paintings of birds ever produced. Barraband died at a comparatively young age in Lyon.

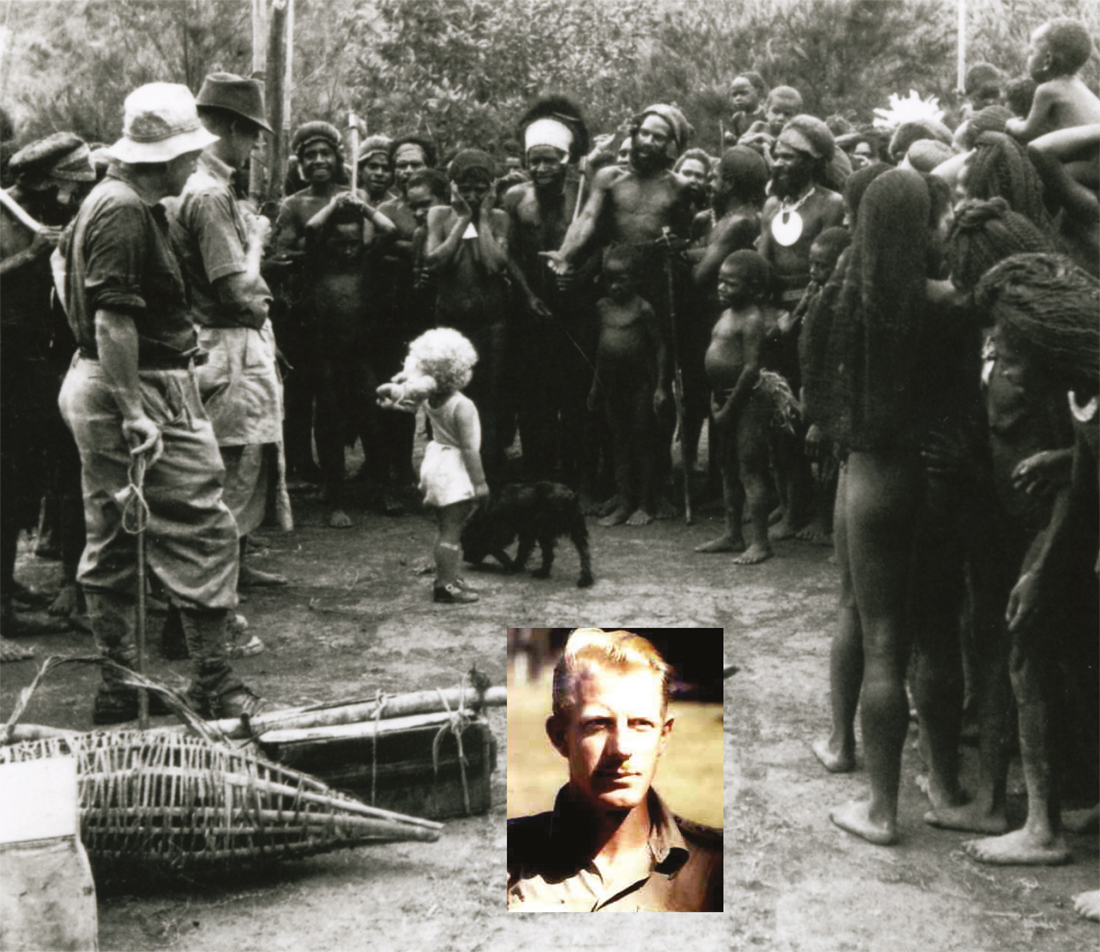

Captain Neptune Newcombe Beresford Lloyd Blood (1907–78?) (pictured with his daughter second from left, and inset) is something of a man of mystery. Even the date of his death remains uncertain. His daughter recalled him as a modest man who thought little of his exploits, yet he was responsible for saving many servicemen from the rigours of New Guinea’s jungles during World War II. He made several important contributions to ornithology and botany during his New Guinea patrols in the 1940s and 1950s.

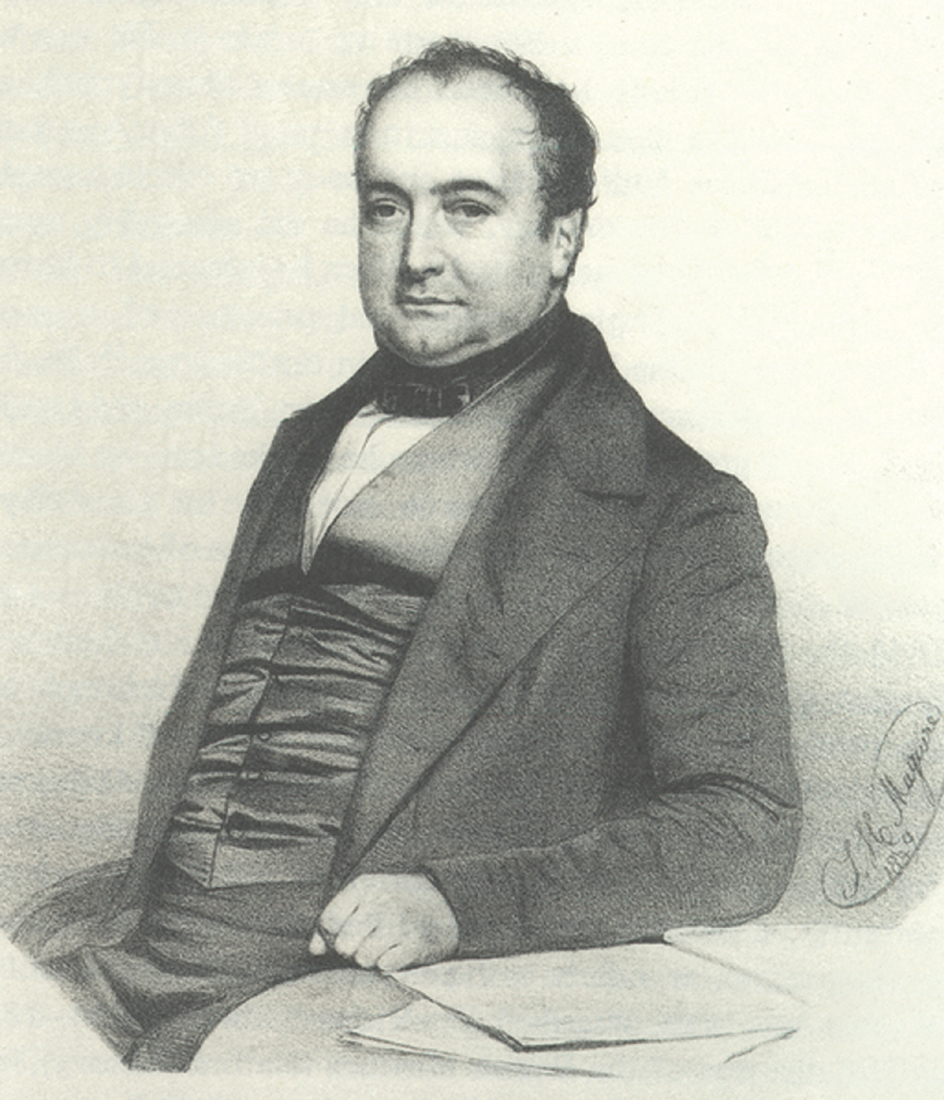

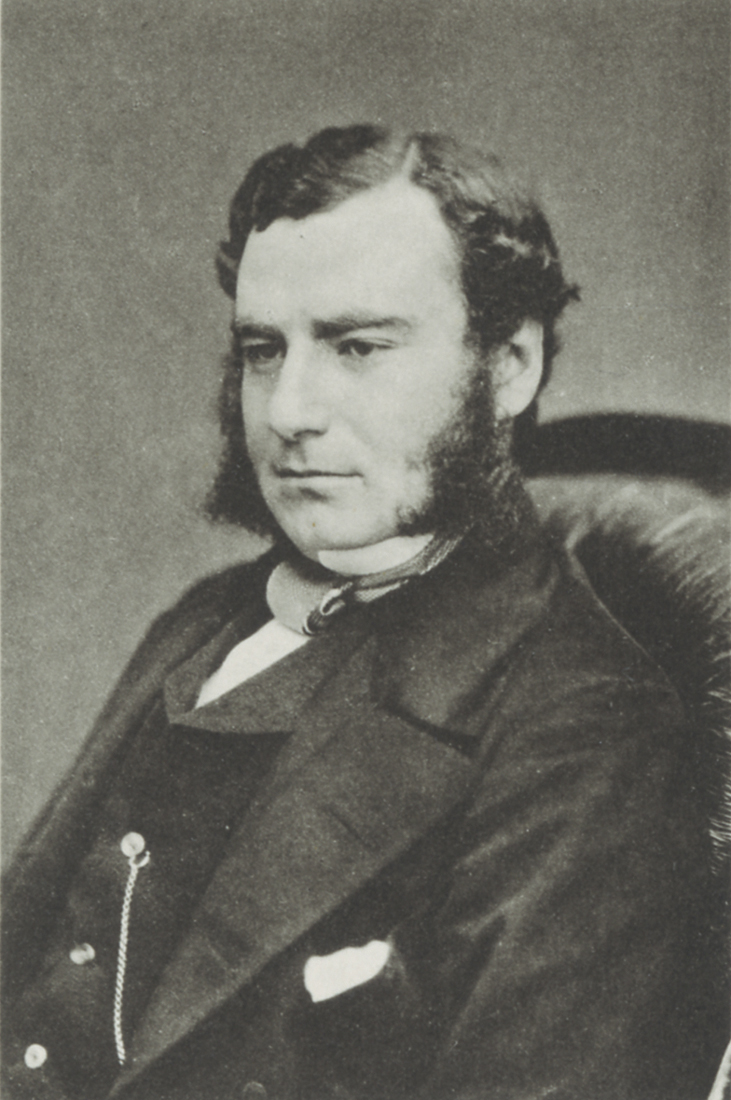

Charles Lucien Bonaparte (1803–57) was a nephew of Napoleon, and he spent much time in America where he championed John James Audubon. His great love was natural history but he was unable to shake off the family association with politics. A great supporter of democracy, he took part in various revolutionary activities and found time to father 12 children.

Raymond Ching (1939–) is widely acclaimed as one of the world’s most accomplished painters; natural history pictures are only part of his artistic repertoire. A New Zealander by birth, he has maintained studios in both his home country and in England, and his paintings have been exhibited in many parts of the world. Despite the wide range of his subject matter, birds of paradise are among his earliest and greatest interests.

Carolus Clusius (1526–1609). Charles Lecluse, to give him his un-Latinised name, became Prefect of the Imperial Viennese Medical Garden in 1573, but his natural history interests were broad and he had access to the emperor’s cabinet of curiosities. There he saw a bird of paradise skin and realised that the stories of the birds’ leglessness were mere myths. In 1593 he became a professor at Leiden University and established one of the first scientifically organised botanic gardens. But he also regularly visited docks to check on curiosities being brought back by ships from the east. As a horticulturalist, he became expert in breeding tulips with streaked and feathered petals and so became a key figure in the ‘tulipomania’ that swept western Europe in the 1600s.

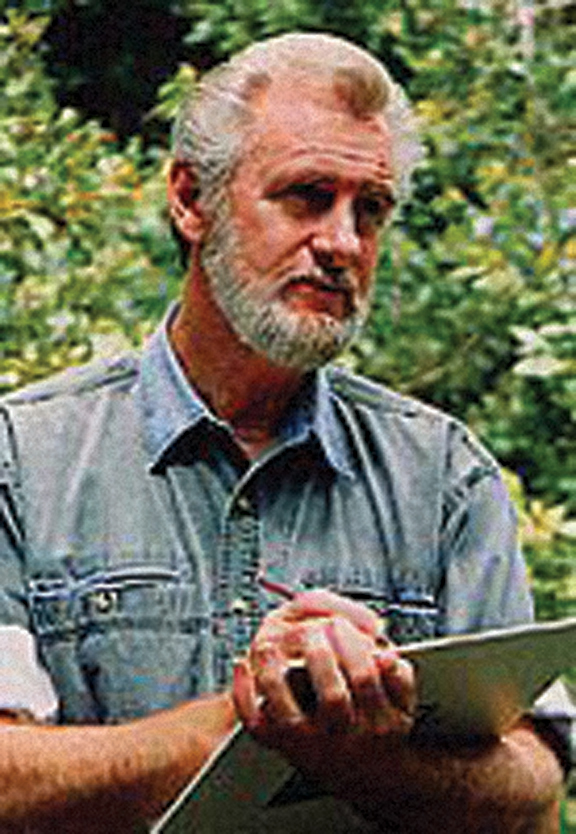

William Cooper (1934–). Australian born and bred, he began his career as a landscape painter but in 1968 he produced A Portfolio of Australian Birds, which immediately put him on the foremost rank of bird painters. Soon he took on the tradition established by John Gould and started to produce large-folio volumes containing paintings of all the species of a particular family, together with a text written by a taxonomist. His plates of birds of paradise, with texts by Joseph Forshaw, were published in 1977, but he has also produced equally authoritative and spectacular volumes on parrots, kingfishers, hornbills, and turacos. He lives with his botanist wife, Wendy, and paints birds, surrounded by the rainforest of northern Queensland.

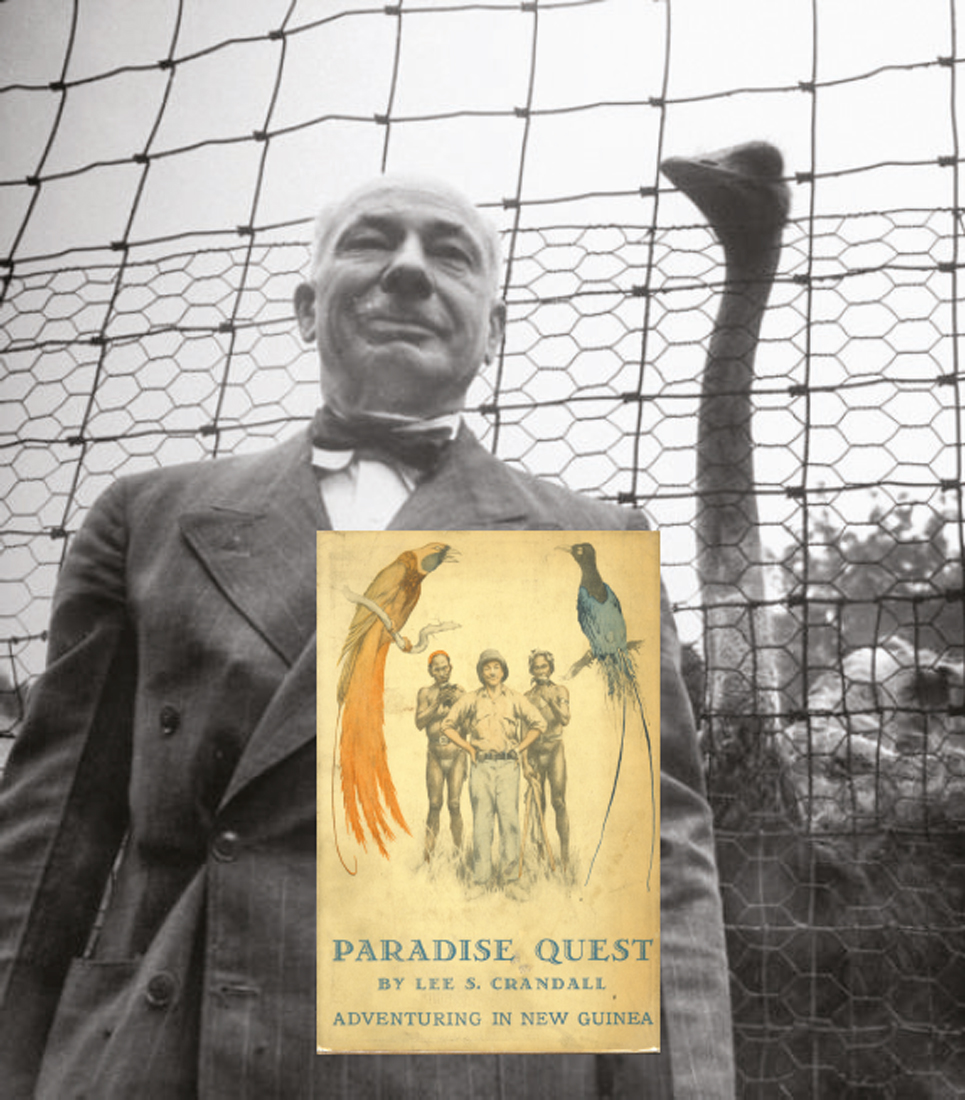

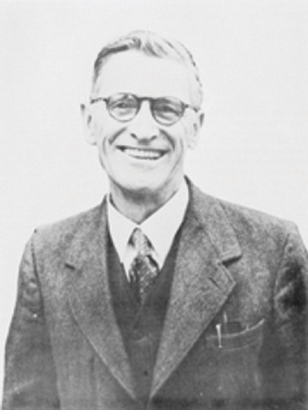

Lee Crandall (1887–1969). For many years Lee Crandall was the curator of the Bronx Zoo, New York, and was responsible for many innovations at that institution. His interest in birds of paradise resulted in his celebrated field trip to New Guinea during the 1920s, and the interesting book, Paradise Quest, which details his exploits. Subsequently, Crandall made observations of several species displaying in captivity, and for many years these observations were the only ones of their kind. Even today, they are still quoted. When asked why he was so interested in birds, Crandall always gave the same answer – ‘I don’t know’.

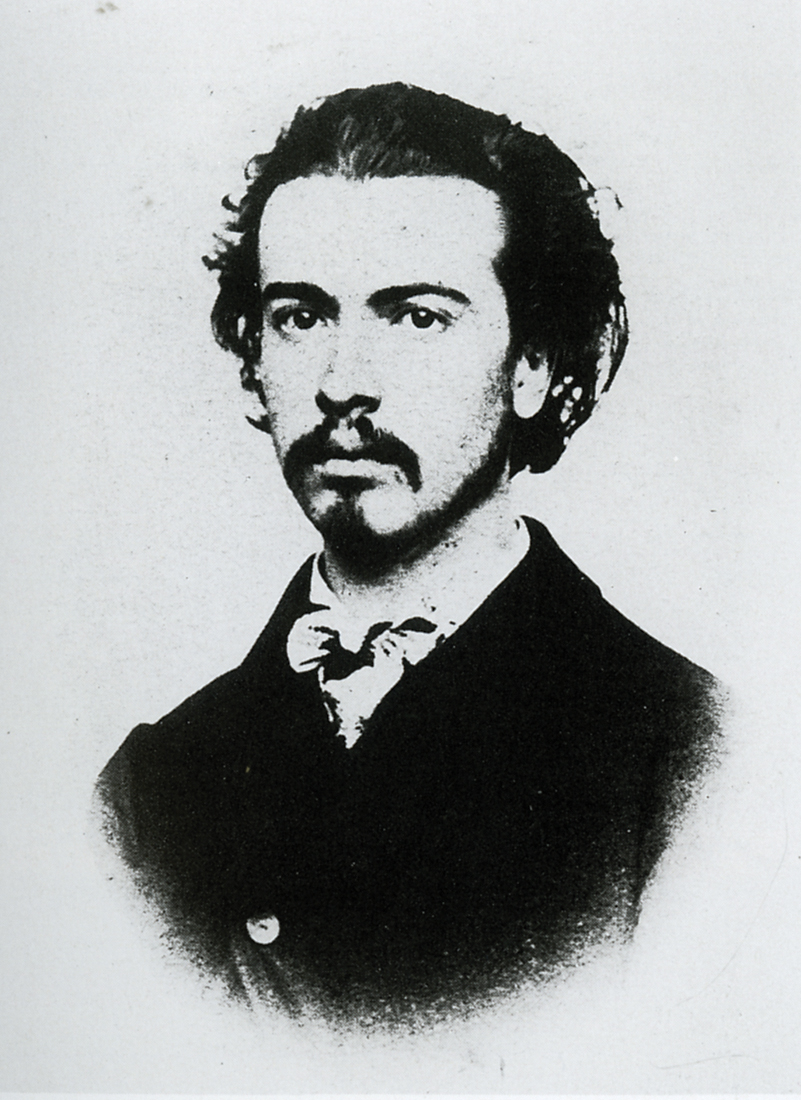

Luigi Maria D’Albertis (1841–1901) was a flamboyant Italian aristocrat who made significant contributions to the exploration of New Guinea. His most celebrated New Guinea adventure was to steam up the River Fly, for a distance of almost 1,000 km (600 miles), in a launch called the Neva. The voyage was an eccentric one, and included such acts as letting off fireworks to scare away hostile natives, engaging in pitch battles when such actions didn’t work, and keeping a pet snake on board to inhibit the pilfering of supplies. Weariness and ill health led to his return to Italy with important collections of natural history and ethnographical material. He retired to Rome where he lived alone, and died from cancer of the mouth. He once remarked that in his opinion it was easier to cross the Alps than to ascend an ordinary hill in Papua.

François Daudin (1774–1804). Despite having legs paralysed by a childhood disease, François Daudin excelled in physics and natural history. He became an expert in ornithology and the study of reptiles and amphibians. Although he published several important books during his short life, these were commercial failures, and he and his wife lived in poverty. She died of tuberculosis and he followed her less than a year later.

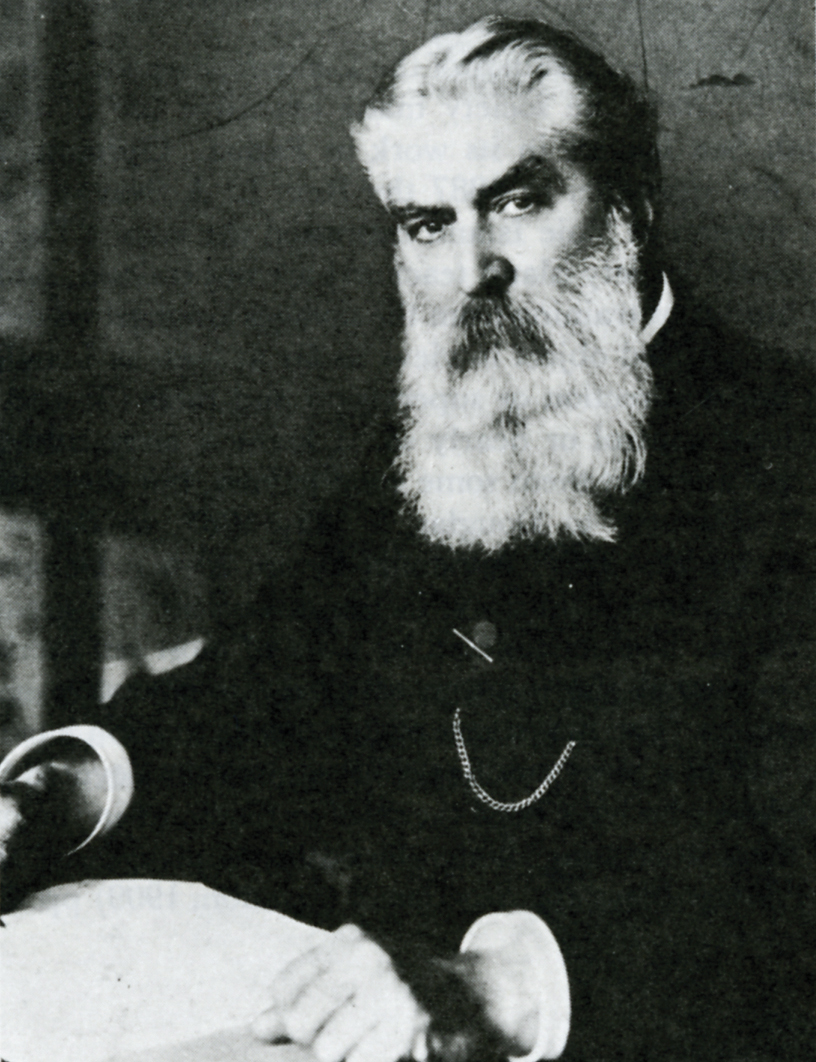

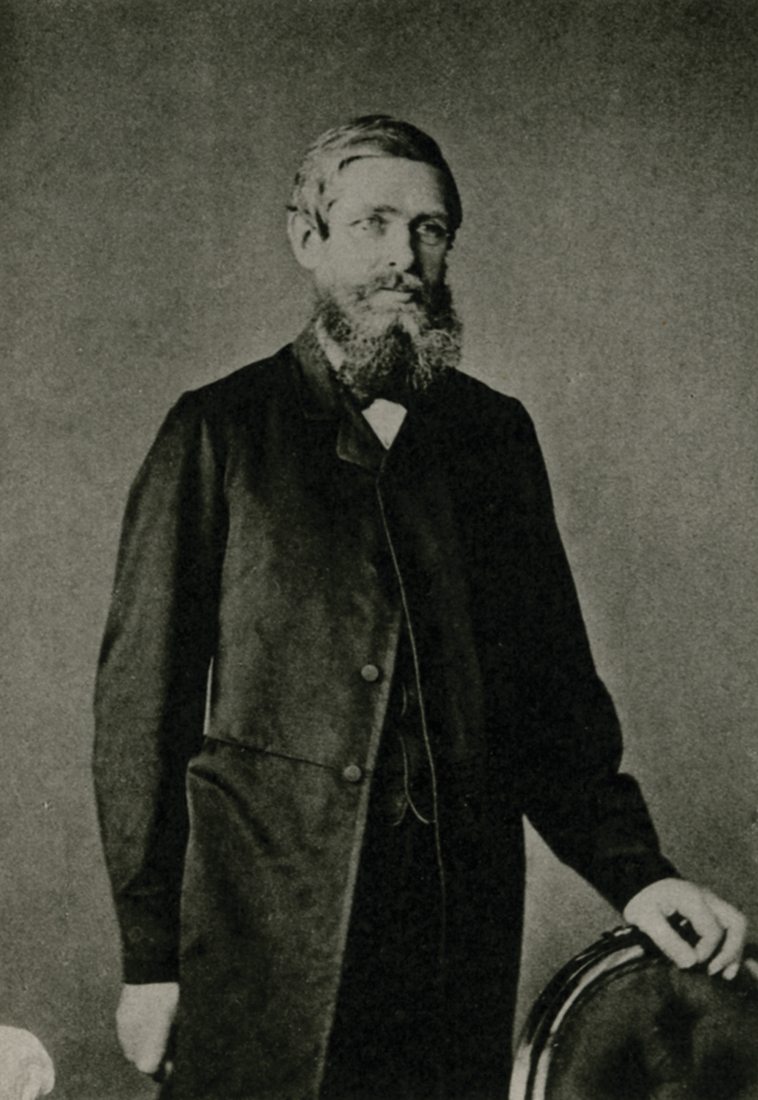

Daniel Giraud Elliot (1835–1915) had both a passion for birds and a great deal of money. He assembled one of the finest collections of bird skins in private hands. This was eventually acquired by the American Museum of Natural History, New York, of which he was one of the founders. He finished his scientific career as keeper of ornithology at the Field Museum in Chicago. He was both a competent artist and a lover of fine books and was determined to follow the fashion established by John Gould, and if possible improve upon it. He published his first book, on Pittas or Ant-Thrushes, in 1861 and illustrated it with his own drawings and others by Paul Louis Oudart. Then followed two other even larger volumes – on grouse, and a collection of previously un-illustrated North American birds in which his own work was once again supplemented by others, including the great Joseph Wolf. Next he tackled pheasants. And then the birds of paradise. The plates for these were once again drawn by Joseph Wolf. The volume on birds of paradise contains 37 hand-coloured plates, each c.60 cm × 45 cm (24 in × 18 in) when trimmed for binding – a size known as elephant folio. It must count as one of the most sumptuous of illustrated bird books, and Elliot, very appropriately, dedicated it to Alfred Russel Wallace.

Errol Flynn (1909–59). Adventurer, bar-fly, beachcomber, boxer, brawler, drifter, entertainer, freedom fighter, lover, platypus and bird fancier, prospector, self-confessed thief, sailor, writer, Hollywood icon, Errol Flynn packed almost every conceivable human activity into his whirlwind tour through life. He starred in almost 60 films, wrote two novels and an autobiography, before dying at the comparatively early age of 50 from the effects of a totally worn-out body.

Bruno Geisler (1857–1945) collected birds and ethnographical artefacts in New Guinea and other parts of the South Pacific, mainly for the Dresden Museum. He became the museum’s taxidermist but is best known for the paintings of birds that he produced for several important German publications.

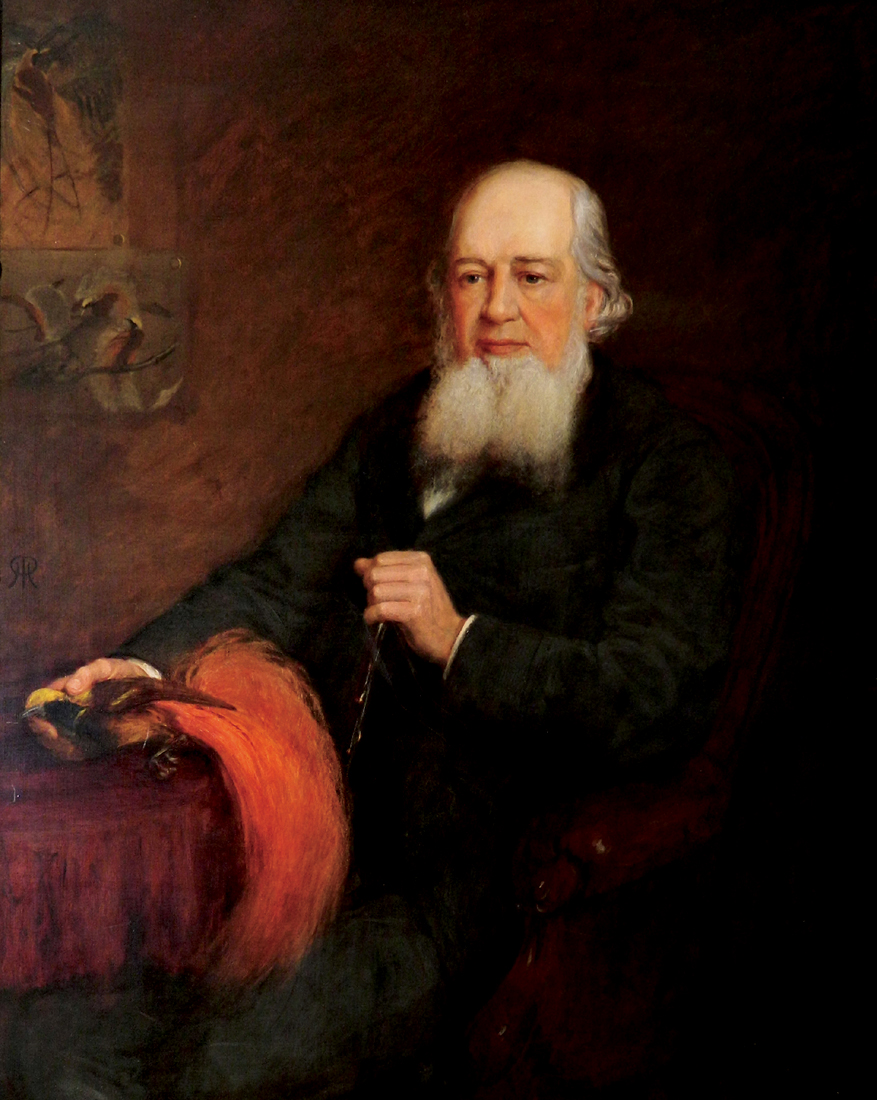

John Gould (1804–81), the son of a gardener working at Windsor Castle, was in 1827 appointed curator at the newly formed Zoological Society of London with the responsibility for preserving and mounting the bodies of many of the animals that died in the Society’s gardens – the London Zoo. While there, he began publishing illustrations of some of the birds whose skins were sent to the Society for classification. Initially, these were drawn by his wife, Elizabeth, and she continued as his principal artist for ten years thereafter. She died in 1841 at the age of 37, after giving birth to their eighth child. Gould, now operating as an independent publisher, engaged a series of other artists to draw his plates. Eventually he produced just one short of 3,000 of them. His work of classifying and often naming species gave him a considerable reputation as a taxonomist, and he was called upon to pronounce on whether the different specimens of finches brought back by Darwin from the Galapagos were in fact separate species or just local variants. Perhaps the least of his talents was the one with which he is most widely credited – painting birds.

John Gould with a specimen of Count Raggi’s Bird of Paradise. Two paintings of birds of paradise, perhaps preliminary studies, are pinned to the wall. H. R. Robertson, 1878. Oils on canvas, 127 cm × 101 cm (50 in × 40 in). Private collection.

Henrik Gronvold (1858–1940) was a Danish-born illustrator who travelled to Britain and, towards the end of the nineteenth century, took over the mantle of the great, but ageing, bird illustrators like Keulemans, Wolf and Hart. He particularly excelled at painting birds’ eggs.

William Matthew Hart (1830–1908) produced a huge number of lithographic plates of birds, based on his watercolours and oils – many of them for John Gould – but little is known of him and he has received only limited credit for his efforts. Born in Ireland, he spent most of his life in Camberwell, south London, and he is buried in the cemetery there.

Jack Hides (1906–38). Between the two World Wars, in the 1920s and 1930s, the eastern half of New Guinea was administered by an extraordinary group of young Australians. Aged mostly in their twenties and thirties, they led locally recruited men, known as policemen (shown with Hides), on patrols lasting months through little-explored and often totally unknown country, full of people armed with spears and stone axes who did not necessarily welcome visitors. Jack Hides led one of the most daring. So proud were his men of their government positions, and so disciplined their conduct, that they were quite prepared to give their lives during these arduous expeditions. The dying words of one were, ‘My light is going out, but it doesn’t matter – I am wearing the judge’s coat’ – a reference to Judge Murray, then head of New Guinea administration. Hides published several interesting and revealing accounts of these explorations, including Through Wildest Papua (1935), Papuan Wonderland (1936) and Savages in Serge (1937). He then resigned from the public service, and in 1937 led an expedition prospecting for gold. Like many before him, he had no success, and, perhaps debilitated from all the hardships he had endured, he died from pneumonia soon after his return.

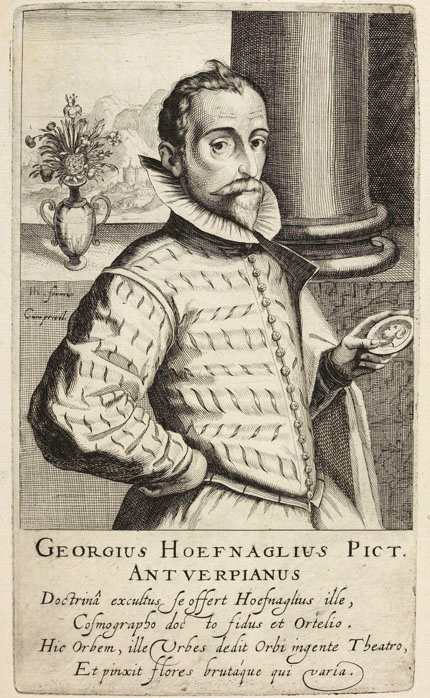

Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601) and Jacob (1575–1630). Joris (George) Hoefnagel was a Flemish-born painter and engraver who travelled to make a living. In his twenties he was in England where he painted a well-known picture of a wedding at Bermondsey; he also produced an early map of London. Later, he spent time in Munich before working for Emperor Rudolf II in Prague and Vienna. His son Jacob carried on the family tradition, and it is not always certain which of the animal pictures produced for the emperor were by the father and which were by the son.

Carl Hunstein (1843–88). Leaving Germany as a young man Hunstein travelled to America and then New Zealand, before moving on to New Guinea in search of gold. This proved something of a failure, and he joined forces with fellow Germans in search of birds of paradise. He was enormously successful and discovered several new species, but died in a tsunami while searching for others. It is said that during seven years among hostile tribes, he never once had occasion to use violent means of defence – preferring other ways of avoiding trouble.

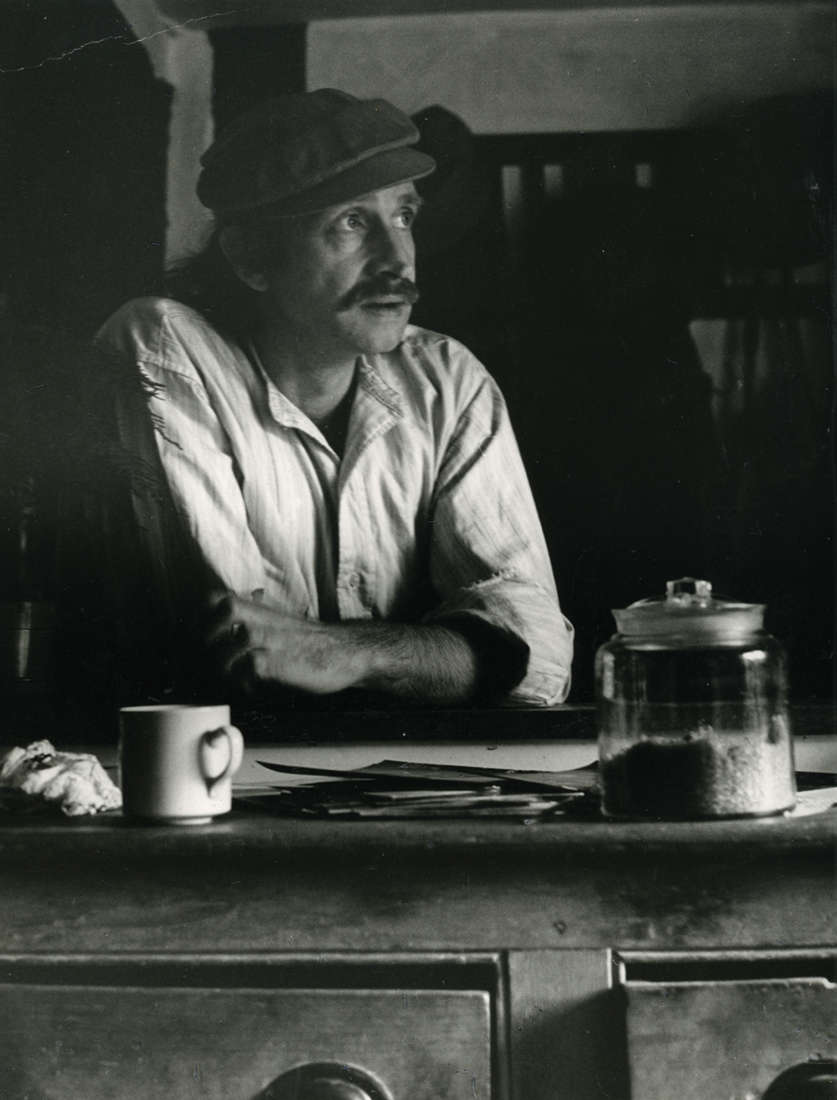

Tom Iredale (1880–1972). Raised near Workington close to the English Lake District, Tom Iredale travelled to New Zealand and then Australia where he pursued a career in museums, specialising in conchology and ornithology. He produced wildly eccentric books setting himself very much against ornithological orthodoxy. During the early 1950s his books on birds of paradise and the birds of New Guinea were made in conjunction with his wife, the painter Lilian Medland.

John Gerrard Keulemans (1842–1912) was an illustrator in Leyden when he came to the attention of Richard Bowdler Sharpe, who asked him to illustrate a book on kingfishers, and then persuaded him to settle in England. They worked closely together for the next 30 years. His work was soon sought after all over Europe for journals and books. The style changed little, with birds nearly always perched or at rest, and details of beaks, feet and plumage defined with meticulous accuracy, Foregrounds, leafy or rocky, are detailed and backgrounds fainter and more sketchy. His images were usually reproduced by lithography and often transferred to lithographic stone by Keulemans himself. He also provided such a service for other artists. In personality he was shy, polite, taciturn and withdrawn, totally absorbed, it seems, in his work.

Charles R. Knight (1874–1953). Although famed for his iconic and evocative images of dinosaurs and other prehistoric life, Knight regarded himself primarily as a painter of living animals and birds, and based his restorations of fossil remains on a lifelong study of extant creatures. A close connection with the Bronx Zoo and the animals that were constantly arriving there helped enormously in this. Curiously, he was regarded as legally ‘blind’ due to astigmatism and an injury to his right eye.

John Latham (1740–1837) was born at Eltham, then in Kent, and started working life as a medical doctor at nearby Dartford, but he had been fascinated by birds as a child and he continued to collect and draw all the specimens he could obtain. His medical practice flourished and earned him so much money that he was able to devote himself to his ornithological studies. His ambition was to list every bird known to science and where possible illustrate them with engravings that for the most part he drew, engraved, printed and coloured himself. His first publication, A General Synopsis of Birds, appeared in 1781. Five more volumes followed in 1785 and further supplements in 1787 and 1801. By this time his fortune was spent but he continued working, trying to keep pace with the new species that were flooding into Britain as explorers opened up the world. In 1801 he started on a new edition of his Synopsis which he called A General History of Birds. It contained 193 plates and listed 3,000 species. He continued drawing new species until just before his death in 1837 aged 97.

Reverend William Lawes (1839–1907) of the London Missionary Society spent much of his life at Port Moresby and translated the New Testament into Motu, the local language. A Six-wired bird of paradise, Parotia lawesii, was named in his honour.

René Primevère Lesson (1794– 1849), served in a medical capacity aboard one of the French exploratory expeditions to the South Seas. His great interest in natural history led him to collect specimens and make observations of the animals and birds that he saw. He was the first European naturalist to see birds of paradise in the wild. On his return to France he published several books on natural history subjects including one on birds of paradise, Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux de Paradis et des Epimaques.

François Levaillant (1753–1824), was born in Surinam (now the Republic of Suriname), studied in Europe, and made expeditions to Africa. Following these he wrote several lavish books, including a six-volume treatise on African birds, and he formed a collaboration with a number of artists, including Jacques Barraband, who painted hundreds of pictures for him. Levaillant went on to publish magnificent books on several bird families, but despite the sumptuous nature of these, he died in poverty.

Carl Linnaeus (1707–78). Carl von Linné, to use the Swedish version of his Latinised name, devised the system by which living organisms are given a universally recognised two-word scientific name. The first allocates an individual to a group of closely related organisms that he called a genus. Paradisaea, for example, is the generic name of closely related birds. The second name, such as apoda, defines the species to which a creature, in this case the Greater Bird of Paradise, belongs. Linnaeus, shown here in the dress of a Laplander, whose country he explored, was professor of medicine at Uppsala University, before he took the University’s Chair of Botany.

Ferdinand Magellan (1480–1521). The celebrated expedition that Magellan commanded completed the first circumnavigation of the Earth. Setting sail from Spain and rounding Cape Horn into the Pacific, the expedition returned to Spain by way of the Cape of Good Hope. It is often stated that Magellan completed the circumnavigation himself. He didn’t. He was killed during a battle in the Philippines, wounded first by a bamboo spear and finished off with other weapons. Only one of the five ships that originally set sail managed to return to Spain, and out of 237 men who had participated in the expedition, just 18 returned alive.

Lilian Medland (1880–1956), pictured with her husband Tom Iredale and their children Rex and Beryl, was born in Finchley, north London and, for the period, grew up to be a very independently minded woman, smoking and engaging in such activities as rearing lion cubs and raising salamanders. An attack of diphtheria when she was 27 left her deaf, but she continued to enjoy all sorts of outdoor activities. She moved to the Antipodes and married Tom Iredale – retaining her maiden name – later helping him with his various publishing projects and contributing illustrations. Her many paintings of birds of paradise – produced for his books – may lack technical finesse, but they have considerable charm.

Adolf Bernard Meyer (1840–1911) was instrumental in the development of the natural history museum at Dresden into one of the world’s great collections. He showed particular interest in rare and curious forms and also in birds of the South Pacific, especially birds of paradise.

Alfred Newton (1829–1907) was a crusty yet highly respected professor of zoology, but he wrote surprisingly poetic passages on ornithological matters close to his heart. His pet subjects were the Great Auk and the Great Bustard. He wrote a ground-breaking Dictionary of Birds, and one of the great classics of ornithological literature, Ootheca Wolleyana.

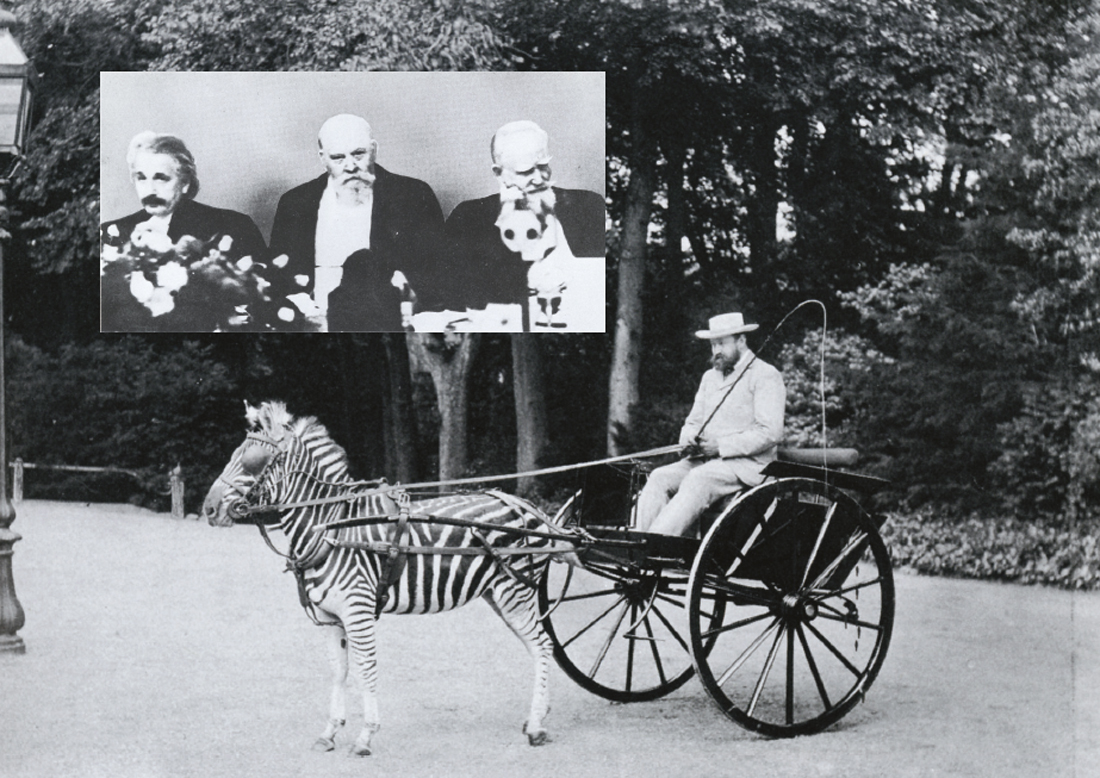

Walter, 2nd Baron Rothschild (1868–1937), shown with his zebra and trap and (inset) with Albert Einstein and George Bernard Shaw. In his day Rothschild was one of the most remarkable figures in zoology. A scion of the celebrated banking house, he proved himself entirely unsuitable for the activities for which his family was famous. Instead, he turned his attention to natural history and formed a fantastic collection of specimens and associated items, as well as a magnificent library; he also founded and funded a scientific journal, Novitates Zoologicae. Blackmailed by a woman with whom he’d had an affair, he was eventually forced to sell much of his collection, including most of his beloved bird of paradise specimens.

Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor (1552–1612). Enthusiasm for art and science has been blamed for the political disasters of Rudolf’s reign. Moving the Habsburg capital from Vienna to Prague in pursuit of his preoccupation, he made magnificent collections of paintings, sculpture, weapons, and all kinds of musical and scientific instruments, as well as living animals including birds. A long, indecisive war with the Turks ultimately led to his downfall. With no legitimate issue, he was stripped of power by his younger brother.

Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria (1858–89). Son and heir of Franz Josef, Emperor of Austria, Hungary and Bohemia, Rudolf was destined to rule over the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire. But he quarrelled with his father over a number of issues and, apparently, committed suicide with his lover, Mary Vetsera, at a hunting lodge known as Mayerling. This set in motion a chain of events that ultimately brought about the end of the Habsburg Empire and the start of World War I.

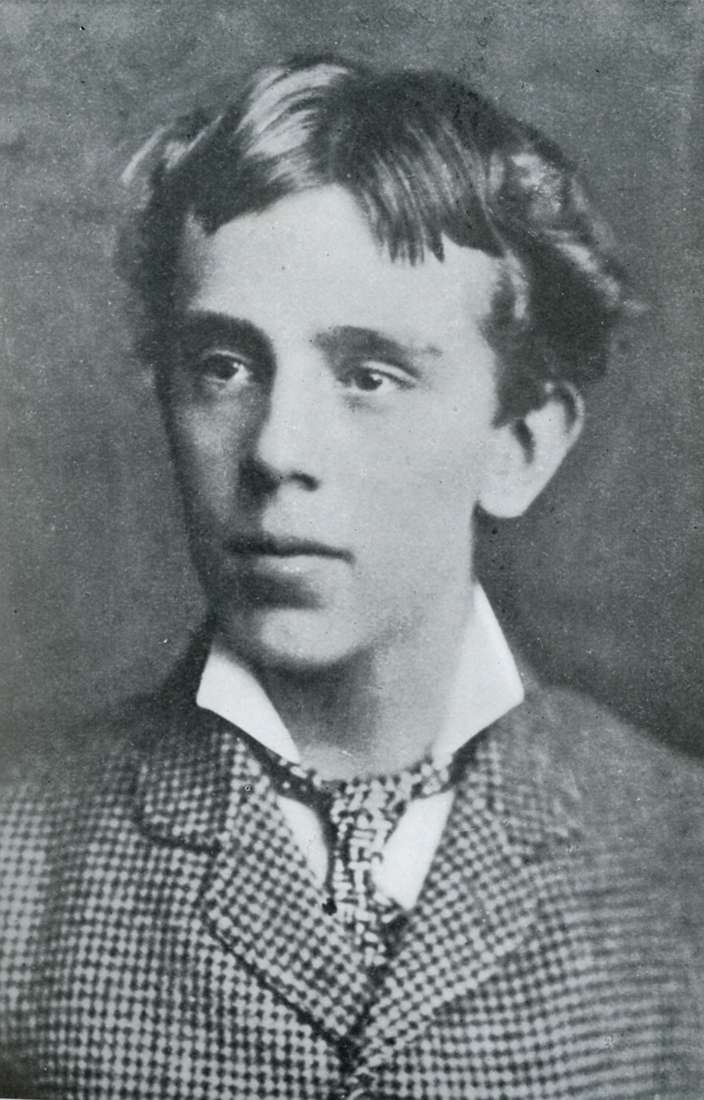

Richard Bowdler Sharpe (1847–1909), is an interesting and unusual character in the history of nineteenth-century ornithology. From fairly modest beginnings worked his way up to a position of considerable prestige in the zoological world and produced a number of important books. He met John Gould, who had a profound influence on his life, while fishing near Cookham in Berkshire, and he met his wife while wandering in the woods there. The married couple went on to have no fewer than twelve daughters, some of whom helped very expertly with the hand-colouring of plates for his books. His happy home life was shattered when he died suddenly on Christmas Day in 1909.

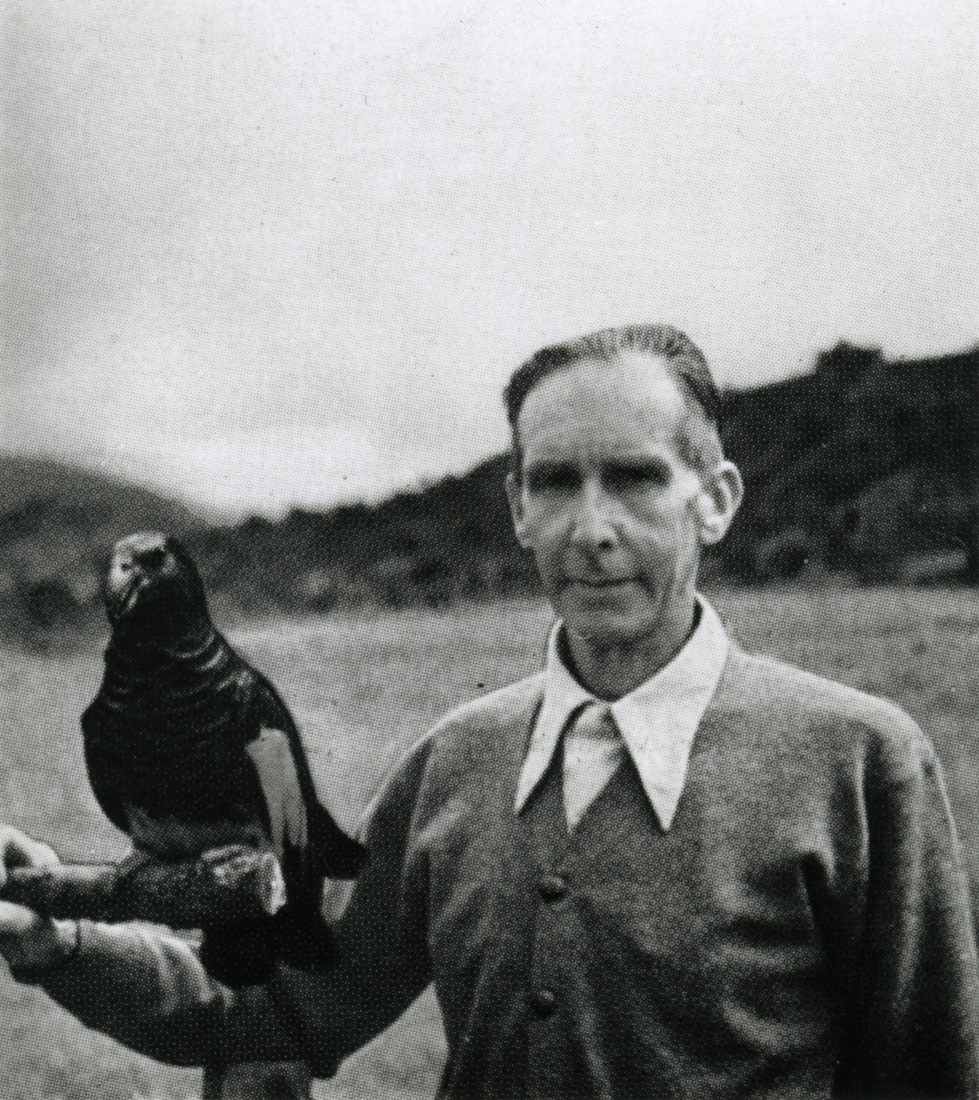

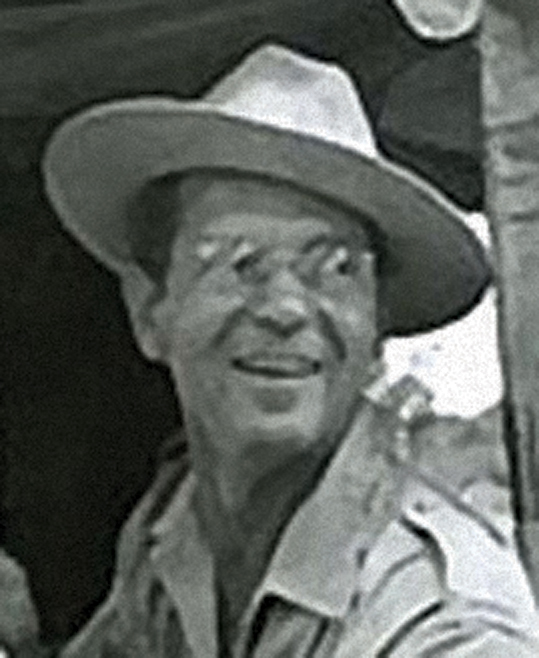

Fred Shaw Mayer (1899–1989) is shown here holding his tame Pesquet’s Parrot, a species which is found only in New Guinea. He was one of the last men to earn a living by collecting birds and animals and selling them, alive or dead, to museums and wealthy collectors. After working in many of the wilder parts of the Far East and the Pacific, he ended his career in charge of huge aviaries, full of birds of paradise, at Nondugl in the Wahgi Valley in the Central Highlands of New Guinea. The gardens there had been founded by Captain Neptune Blood, but the aviaries had been paid for by an Australian industrialist and bird enthusiast, Sir Edward Hallstrom, who intended that the birds should be sent to Taronga Park Zoo in Sydney, and to other zoos and parks in Europe. Eventually, however, Australian quarantine laws made exporting them impossible. Better known than Shaw-Mayer’s tame parrot was a pet Count Raggi’s Bird of Paradise which regularly performed displays for visitors to Nondugl. So popular did this bird become and so closely associated with Fred Shaw Mayer that it was known to those who saw it as ‘Fred Raggiana’. When he finally entered a retirement home in Australia, two aviaries were built in the grounds so that he could continue looking after his birds.

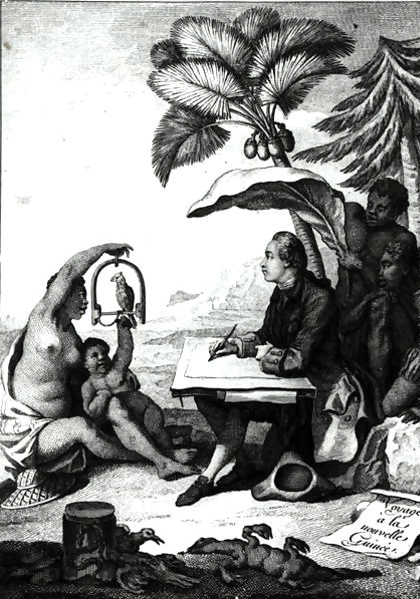

Pierre Sonnerat (1748–1814), pictured on the frontispiece of his book Voyage à la Nouvelle-Guinée, was in many ways a ground-breaking naturalist and explorer. Yet many of his written observations need to be taken with a pinch of salt. Despite this qualification, his books are fascinating and full of interest. Setting out from France, he travelled several times to Southeast Asia, and on to China, the Philippines and the Moluccas. He also visited Madagascar. He held some remarkably modern views on a number of matters, including the subject of racism. Being particularly impressed with the various cultures of India, he regarded the Brahmins as the most enlightened of all human beings.

Princess Stephanie (1864–1945). A Belgian princess by birth, she married Crown Prince Rudolph when she was just sixteen, and expected that one day she would rule over the Austro-Hungarian Empire. However, she was widowed when Rudolph committed suicide at Mayerling. Before this tragedy, the royal pair had birds of paradise named after them and Stephanie’s was a newly discovered Astrapia. After Rudolph’s death Stephanie married a Hungarian count – apparently appalling certain members of European aristocracy who thought the marriage was beneath her. In her later years she wrote an autobiography titled I Was To Be Empress.

Samuel Stevens (1817–99). Little is known of Stevens, and had he not operated as Alfred Wallace’s agent his name would have faded into history. However, he opened a natural history agency in London during 1848, one of his specialities being slides for the microscope, the material for which was sometimes obtained from Wallace and his fellow explorer Henry Bates. Doubtless, he handled the sale of many of the bird of paradise skins that Wallace sent back from his travels.

Erwin Stresemann (1889–1972), pictured being tattooed with the sign of the headhunter in Ceram during 1911, was born in Dresden of wealthy parents and travelled widely as a young man. He settled to become Curator of Birds at the Berlin Museum and one of the most distinguished ornithologists of his day. His most lasting achievement is the compilation of the Aves volume for the Handbuch der Zoologie, but perhaps of more interest to the general reader is his book Ornithology from Aristotle to the Present. His influence over a younger generation of evolutionary biologists was huge, and such was his prestige that after World War II he was allowed to travel freely through the divided city of Berlin from his home on the west side to the museum – which was in the eastern sector.

Carola Vasa (1833–1907), Queen of Saxony. As a young girl, Carola was considered one of the most beautiful of the royal princesses of Europe. A descendant of a deposed Swedish king, she married Albert of Saxony (with whom she is pictured), and became the last Queen of Saxony. Due to Saxony’s connection (through the Dresden Museum) with the discovery of birds of paradise, both she and her husband gave their names to new species. Pteridophora alberti was named after the king, and is still popularly known as the King of Saxony’s Bird of Paradise, and Parotia carolae is still called Queen Carola’s Six-wired Bird. She interested herself in social issues and became an ardent supporter of nursing and the women’s movement. Among other good works, she founded homes for the sick and handicapped.

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913). Wallace’s fame as a scientist rests primarily and justly on his co-authorship with Charles Darwin of the theory of evolution by natural selection that had occurred to him during a malarial fever when he was pursuing birds of paradise in eastern Indonesia. Far from resenting the fact that the theory became identified primarily with Darwin, he recognised that this was only just since Darwin had already assembled a huge mass of supporting evidence.

Wallace left school aged 14, but he was already fascinated by the natural world. After a few years spent assisting his brother as a surveyor and teaching at a school in Leicester, he left Britain to start exploring the tropics, first in Brazil and then Indonesia. He paid his way by sending batches of natural history specimens back to Europe where they were sold by his agent to wealthy enthusiasts. During his Indonesian journey he collected and prepared over 125,000 specimens. When, after eight years, he himself returned, he brought with him two living Lesser Birds of Paradise that he had purchased in Singapore. These he sold to the London Zoo for £300 plus free entry to the zoo. They may have been the first living birds of paradise to reach Europe, except for one that had been kept by the royal family at Windsor and had died 40 years earlier. During his last years he devoted himself to writing works not only on biogeography but on social issues such as land nationalisation and female suffrage, both of which he vigorously supported. He died, greatly honoured, aged 90.

Walter Weber (1906–76). Born in Chicago, one of eleven children, Walter Weber once exchanged a hundred of his drawings for a bottle of soda pop. His fortunes changed, however, and in 1949 he became staff artist and naturalist for National Geographic magazine, and it was for this organisation that he produced his influential images of birds of paradise.

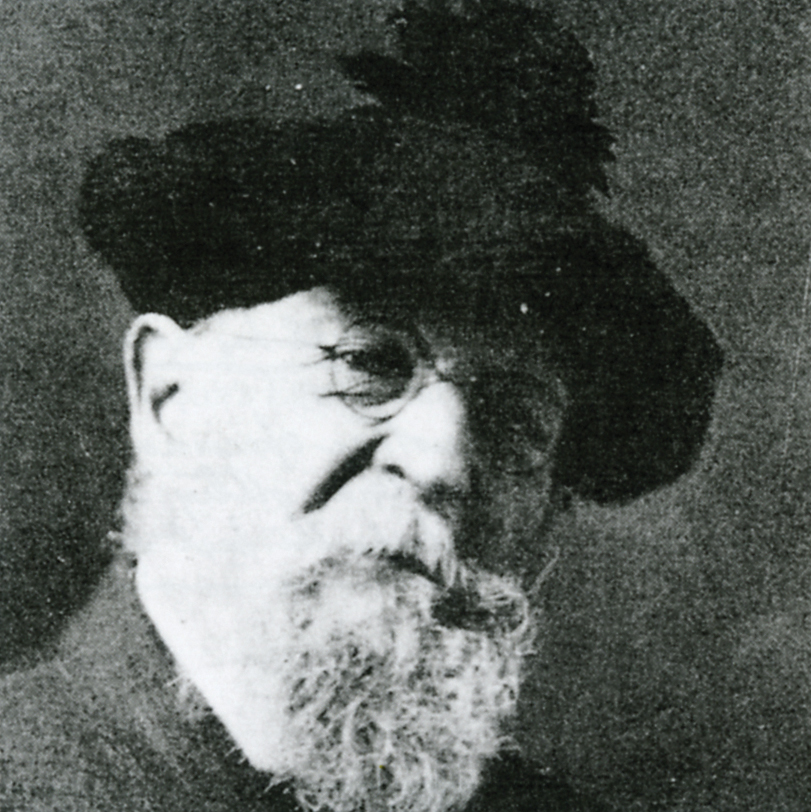

Joseph Wolf (1820–99). German born, Wolf moved to Britain during his late twenties and stayed for the rest of his life. He became one of the most acclaimed animal and bird painters of his era, and his work was sought after by wealthy collectors and publishers alike. Even the great artist Edwin Landseer admired him and once said that he must have been a bird before he became a man! His favourite subjects were, perhaps, birds of prey, but his illustrations of birds of paradise were among his finest achievements.