Two male Arfak Astrapias with a female (detail). Hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Two male Arfak Astrapias with a female (detail). Hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Two male Arfak Astrapias with a female. Hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Genus Astrapia

The Black and Brown Sicklebills are not the only birds of paradise to have developed extravagantly long tails. Another group also has them. These are the Astrapias, birds whose tails, along with the throats and breasts, have become the main physical focus of evolutionary change. There are five distinct species and each has a tail of breathtaking beauty. Males of three species have tail feathers so long and broad that they make the bodies of the birds look tiny in comparison, an illusion reinforced by the fact that each feather widens gracefully and gradually towards its extremity. With a subtle barring that is unnoticeable unless the feathers are examined closely, the spectacular tails are much sought-after by native Papuans as crowning ornaments for their headdresses. A fourth species has a tail shorter in comparison (although by no means short) that terminates in a flattened, slightly rounded bob, while the fifth species may have the most extraordinary tail of them all. Its two central feathers are the longest of any bird of paradise. White in colour, they are extremely narrow for their entire length, and they end in pointed black tips.

The throats and breasts of all these species are equally striking, and almost unbelievable in their depth and richness of colour. On the living bird the variety and combinations of iridescent and lustrous greens, blues, turquoises, pinks, reds and oranges dazzle as the creature twists and turns in the light. In fact they literally fool the eye, for any pigments that might make up these colours are absent. The colour that the viewer perceives is made up by refraction of light. It is the feather’s structure that is the determining factor. At certain angles little or no light is reflected back to the viewer, so the feathers appear black. But as the viewing angle alters, the refracted light creates a whole array of changing iridescent hues and glosses. Birds in the genus Astrapia are not the only species in the family that have developed this peculiarity; many show it to similar effect. Nor is it at all uncommon in birds of other families. There are aspects to the structure of feathers that allow the development of this strange phenomenon, and in creatures such as birds of paradise or hummingbirds it is taken to extreme – and spectacular – levels.

The first Astrapia to reach England was brought, surprisingly, by that great panjandrum of eighteenth-century science, Sir Joseph Banks. In September 1770, Captain Cook in his ship The Endeavour, after sailing up the eastern coast of Australia, threading his way through the treacherous reefs, shoals and islets of the Great Barrier Reef, turned west and passed through the Torres Straits. New Guinea lay just to the north, but the seas along its southern coast were shallow and muddy and it was impossible to make a full landing. Eventually a few men, led by Cook himself, set out in a pinnace and waded ashore. Among the men was the young wealthy Banks who was travelling as ship’s naturalist in some luxury with his own servants. As they walked along the beach Papuans appeared, making hostile gestures and Cook decided to return to the ship. So there is no posibility that his expedition collected any birds of paradise from New Guinea itself, let alone a species that lives in the mountains.

However, The Endeavour continued westwards. The ship was now, after two years away, homeward bound and travelling along the route used by traders carrying spices and bird of paradise skins. Eventually it made landfall at the small island of Savu. Here the Dutch East India Company had a representative, a German named Johan Lange, whose job was to safeguard company interests. He and the local rajah received Cook with some mistrust, but there was an initial exchange of gifts, and Cook decided it was politic to present The Endeavour’s last live sheep to his host. The rajah then took a great fancy to a greyhound that the self-indulgent Joseph Banks had brought with him, and Banks reluctantly handed it over. Maybe the rajah, in exchange, gave Banks a strange black bird skin that had arrived on the island with some of the more usual bird of paradise specimens. If Banks did not acquire it at that meeting, then he almost certainly did so soon afterwards, for The Endeavour stayed on for three days and Banks made a detailed survey of the island.

When at last the expedition reached England, Banks’ strange black bird with its iridescent throat was thought so wonderful that the species was named ‘the Gorgeted Bird of Paradise’. His original specimen, sadly, is now lost. A year or so later, however, further examples arrived in France. There it became known as ‘L’Oiseau de Paradis a Gorge d’Or’.

Eventually the species was given the slightly more prosaic scientific name, Astrapia nigra – the first word meaning ‘shining’ and the second black. Today it is commonly known as the Arfak Astrapia, simply because the species is found only at high altitudes in or near to the Arfak mountains of north west New Guinea. Despite having been discovered more than 200 years ago, the species is still very little known, and such is the apparent rarity of the species that its display has never been observed.

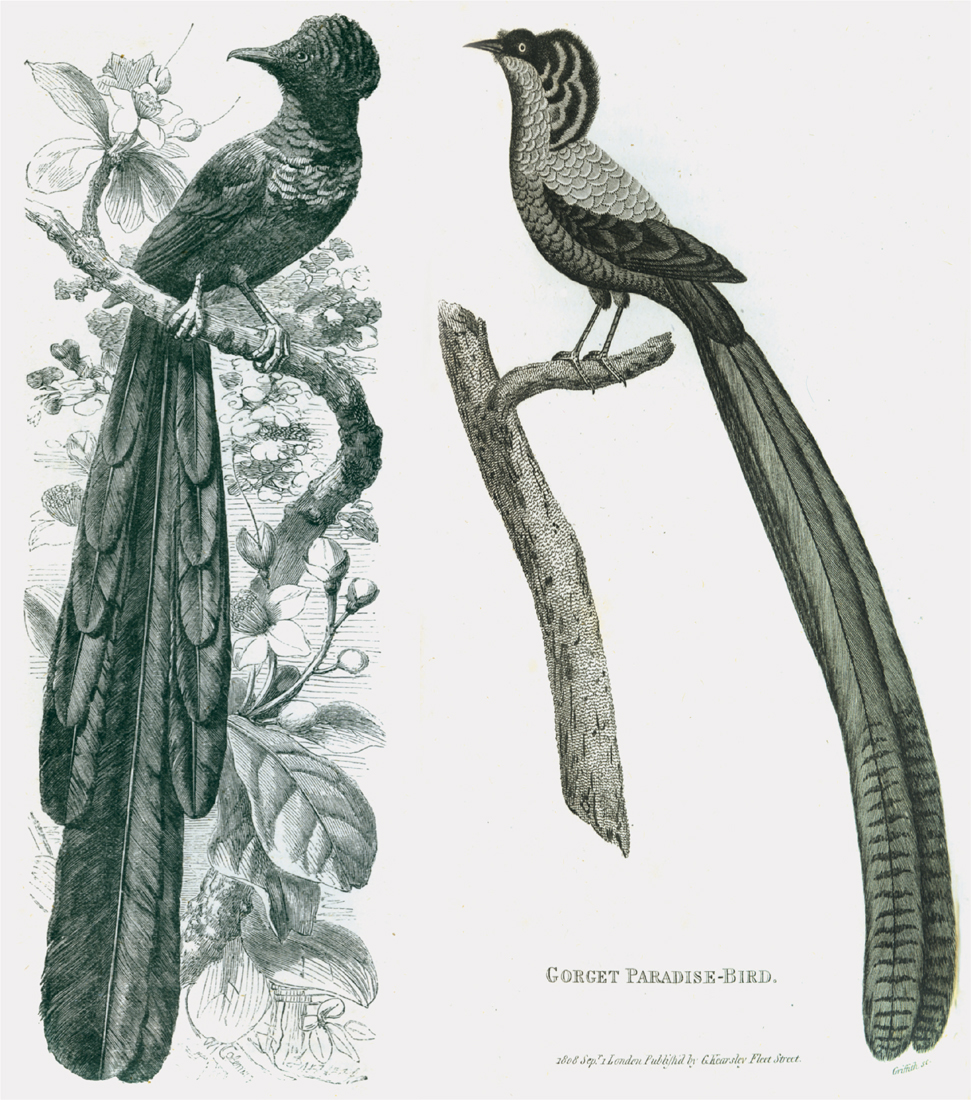

Before it was lost, the English ornithologist John Latham drew a crude portrait of Joseph Banks’ specimen of a male Arfak Astrapia. Later he used his picture to produce this hand-coloured engraving for his book A General History of Birds (1821–1828).

It was more than 100 years before the western world became aware that there was a closely related species. During the year 1884, the German gold prospector Carl Hunstein was working far from the Arfak Mountains. In fact he was operating in the south east, at the opposite end of the great island of New Guinea. Undeterred by grim warnings from friendly Papuans, and accompanied by just a solitary native attendant, Hunstein decided to explore. Climbing high into the jungle-clad mountain ranges, he left civilisation far behind and boldly stepped where no European had gone before. Two years later, in 1886, his German colleagues Otto Finsch and Adolf Bernard Meyer briefly summarised his journey for the English ornithological journal Ibis:

Here the vegetation was sufficient to convince the practised eye that heights had been reached… never before attained. … There appeared a world of new trees and new plants. … The stay in this region, where continuous precipitation renders the preparation of birds very laborious… was an excessively hard task, and one that could only be undertaken by a man of steel and iron… a person of untiring industry and unbroken strength. Avoiding the scattered habitations of the natives, who were by no means friendly, Hunstein passed his time in the bush.

He eventually emerged with three great avian prizes – specimens of three previously unknown (and very spectacular) bird of paradise species. One was the Blue Bird, the second was the Brown Sicklebill, and the third was a new species of Astrapia. Naturally, Hunstein sent his specimens back to Germany for scientific description, and his three new birds were named after Germanic dignitaries. The Sicklebill received Meyer’s name, but the other two species were given rather more illustrious associations. Currying favour with the crowned heads of Europe being a pastime that was very much in vogue, the opportunity was seized to name these two remaining species after a royal couple. The Blue Bird, as has been mentioned, was named Paradisaea rudolphi after Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, and the third bird was called Astrapia stephaniae, after his wife. Sadly, as has been related, the honour didn’t bring the couple much luck and the marriage ended in tragedy when the prince committed suicide. Poor Hunstein fared little better. He perished in a tidal wave during 1888 while trying to reach New Britain in a forlorn search for more new birds of paradise.

The first illustration of Princess Stephanie’s Astrapia (male). Hand-coloured lithograph by Gyulu von Madarasz from Zeitschrift für die Gesammte Ornithologie (1885).

Female Arfak Astrapia. Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

Male and female Princess Stephanie’s Astrapias. W. T. Cooper, 2005. Acrylic on panel, size unknown. Private collection.

Just a few years later, yet another Astrapia species was discovered, and this one has perhaps the most splendid of all bird of paradise throats. Indeed it was given the Latin name splendidissima, which speaks for itself. Commonly known as Rothschild’s Splendid Astrapia, it occurs only in the highlands of central New Guinea and was first described by Walter Rothschild (1868–1937), the eccentric English lord and scion of the famous banking family. Although he never travelled to New Guinea, it was Rothschild – via a network of agents and adventurous naturalists – who, during the last decades of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth, was instrumental in the discovery of many spectacular species – birdwing butterflies, giant tortoises, and cassowaries, as well as birds of paradise. Eventually he acquired so many specimens that he built his own museum for them at Tring, his family home north of London.

Rothschild’s Splendid Astrapia, male. Charles R. Knight. Oils on panel; size, date and present whereabouts unknown. Courtesy of Rhoda Knight Kalt and Richard Milner. Copyright Rhoda Knight Kalt.

There was now a great burst in the identification of new species as explorers, prospectors, entrepreneurs and even governments looked to New Guinea as a potential source of wealth. Three great colonial powers, Britain, Germany and Holland, carved the island apart in a political sense, although none of them was able to make any real inroads in terms of dominating the land. The bulk export of bird skins brought some small revenue but lone explorers, like Hunstein, who when working in the interior lived largely off the land, were allowed to operate freely. Such people quickly realised that money, or glory, could be gained by finding new or rare species and sending specimens back to museums or private individuals, like Rothschild, in Europe or America.

To the modern mind it seems curious that the collecting was almost exclusively of specimens for museums rather than actual living birds, but there are two very practical reasons for this. First, it was almost impossible to keep captive birds alive in the highly dangerous conditions under which the collectors were operating. Second, birds of paradise are not necessarily easy to sustain when removed from New Guinea. Some success has certainly been had, but too often it is short-lived.

An interesting painting of Rothschild’s Splendid Astrapia was produced by Charles R. Knight (1874–1953), the American artist celebrated for evocative and iconic images of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. Although these ‘prehistoric’ pictures were necessarily works of the imagination, Knight’s usual method when painting extant creatures was to use a living model. He was regularly notified when an unusual bird or animal arrived at the Bronx Zoo, and would rush off to sketch it, filling in a fanciful background back home in the studio. Perhaps his model for the Astrapia was a living bird that survived for a while in New York. Birds of paradise were by no means a speciality of Knight’s, so it is difficult otherwise to understand why he would have singled out this rather unusual and little known species as a subject. Certainly, several other bird of paradise species reached New York in the years when Knight was painting.

During 1928 Lee Crandall (1887–1969), Curator of Birds for the New York Zoological Society, undertook an expedition to New Guinea with the intention of securing live birds. Perhaps because he was operating at a comparatively late date with better logistics, he was enormously successful. But the success was also due to Crandall’s sheer determination and bravery. After leaving Port Moresby, Papua’s capital, bound for Australia his ship foundered on a reef. Everyone on board was immediately rescued but Crandall refused to leave without his birds, and these couldn’t be saved at the time. He remained for several days aboard the slowly sinking vessel until arrangements could be made for an evacuation that would include all of the precious birds. He eventually reached America in 1929 with no less than 40 live paradise birds, and he made detailed observations of several of them as they displayed, even though they were in captivity. Among these were a Sicklebill and a species known as the Huon Astrapia.

The Huon Peninsula juts out eastwards from the northeast coast of New Guinea and its mountain ranges are somewhat isolated from the island’s main mountain chain. Presumably, it is this separation that has led to the evolutionary development of several distinct species there. One is a plume bird, the Emperor of Germany’s. There is a Six-wired, Wahnes’, that has developed a long tail very much in contrast to its close relatives, which all have comparatively short ones. And there is the Huon Astrapia, a rather plump creature with a broad, blunt-ended tail that is sufficiently different from other birds in the genus to qualify it as a separate species. Not discovered until 1911, it is another of the forms that first came to light as a result of the collecting mania of Lord Rothschild, and his name is commemorated in its scientific title, Astrapia rothschildi.

Once again, it is the Australian bird specialist W. T. (Bill) Cooper who has produced a definitive picture of the species. He painted it for his monograph on the family that was published in 1977. To produce this superlative work, he spent some time in New Guinea, observing and sketching the birds in the wild.

There is a significant difference between artworks prepared as informative illustrations and paintings produced primarily for aesthetic reasons. In the latter the artist may paint whatever he sees or feels, and if his talent is great enough, he will be able to express precisely those things that he wants to say about his subject by eliminating or highlighting anything that he wishes. The illustrator, however, paints what he knows to be there, whether he can actually see it or not. He is intent on producing a picture of a bird that will include all the details of the creature’s plumage. If he knows that his bird should have six white spots on the wing, he will paint six, even if only five are actually visible on his model. His fundamental job is to inform the viewer of the precise ‘geography’ of his subject. Another artist, pursuing this same subject without the restrictive demands of completeness and precision placed on the illustrator, may choose to paint only what he sees or what he feels about the bird. As he looks at his model, a trick of the light or angle of view may mean that only two of the six white spots are visible and he might, therefore, choose to show only two. In the same idea lies the reason why a hand-drawn illustration may often be more useful than a photograph; the photo will show how its subject appeared at a precise moment in time, but not how it might look at any other.

Two hundred years of Astrapia illustration.

Arfak Astrapia, male. Engraving by W. S. Coleman from J. G. Wood’s Illustrated Natural History (1876).

Arfak Astrapia, male. Engraving by Mrs Griffith from George Shaw’s General Zoology (1809).

Study for an illustration of Rothschild’s Splendid Astrapia. W. T. Cooper, c.1976. Pencil and watercolour, 45 cm × 33 cm (18 in × 13 in). Private collection.

Two paintings of a male Arfak Astrapia, both of which have been subjected to rough handling at some point during their history. Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolours, each 87 cm × 52 cm (35 in × 21 in). Private collection.

These differences of approach are made clear if the paintings of Bill Cooper are compared with those of Jacques Barraband. Most of Cooper’s pictures are conceived as illustrations for twentieth-century bird books, and they achieve their end with great clarity and sophistication. They provide the reader with all the visual information needed to come to an exact understanding of the plumage of the species before him or her.

Jacques Barraband approached things from a rather different position. He, too, was producing pictorial images that would be the basis for a book, but he was working at a much earlier period, when the requirements of these pictures were by no means so clearly defined. Neither did he know (at this comparatively early period) which characteristics were of critical importance in identifying a particular species. In his eighteenth-century studio, he simply placed a stuffed bird (and there need be no doubt that he was using stuffed birds as models) in a certain light, arranged matters so that all was as decorative as possible, viewed the bird from his chosen angle, and proceeded to paint exactly what he saw. The resulting pictures certainly contain many exquisite details of the subject’s plumage patterns, but in terms of a total guide to the bird’s features they are not always as complete as we have come to expect from the work of modern-day illustrators. But what Barraband may have neglected to offer us in completeness of plumage detail, he more than makes up for in the truly startling beauty and power of his pictures.

As far as Astrapias are concerned, there is one more species to be described, but it was discovered at a very late stage and so it is included in ‘The Final Glories’.