Male Paradise Riflebird. Raymond Ching, 1976. Watercolour (details), 73 cm × 50 cm (29 in × 20 in). Genesee County Museum, New York.

Male Paradise Riflebird. Raymond Ching, 1976. Watercolour (details), 73 cm × 50 cm (29 in × 20 in). Genesee County Museum, New York.

Male Paradise Riflebird. Raymond Ching, 1976. Watercolour (details), 73 cm × 50 cm (29 in × 20 in). Genesee County Museum, New York.

Genus Ptiloris

New Guinea is certainly the headquarters of the birds of paradise, but the three species known as riflebirds all live in Australia. It is true that the largest and most spectacular of them also lives on the other side of the Torres Strait in New Guinea, but the two others are exclusively

Australian and don’t occur anywhere else. One of these two species, the Paradise Riflebird, has the most southerly distribution of any member of the family; in fact its range lies hundreds of kilometres to the south of any other bird of paradise.

Yet despite this rather unusual geographical range, the riflebirds are in some other respects fairly typical members of the bird of paradise family, for their appearance conforms to one of the standard body patterns. Like Six-wired birds, or the Superb, they are relatively compact in shape. The males have incredibly soft, black plumage glossed and sheened – according to the light – with grape greens, purples and blues, and they have a roughly triangular breast shield of blue or green that appears to the eye to be made of metal.

Their English name is a puzzle. A specimen that arrived at the Edinburgh Museum in 1824 was labelled ‘Velvet Bird’. This seems reasonably descriptive, bearing in mind the remarkably soft texture of the body plumage, but other slightly later specimens were called Riflebird. Why, is something of a mystery. François Lesson, travelling on the French ship La Coquille which visited Sydney in 1824, stated that it was because the first specimens were shot by a rifleman stationed at Port Macquarie a little farther to the north. Others have suggested that it is because the bird’s call resembles the crack of a rifle, though in fact all three species usually produce a double note. Another possible explanation is that some male riflebirds display standing on the top of a tree stump making themselves very obvious targets for soldiers wanting rifle practice. Yet another suggestion, put forward by an erudite professor of zoology at Cambridge University named Alfred Newton (1829–1907), held that the name probably arose:

because in colouration [the birds] resembled the well-known uniform of the rifle regiments of the British Army, while in the long and projecting…plumes and short tail a further likeness might be traced to the hanging pelisse and the jacket formerly worn by members of those corps.

Although it might be supposed that the riflebirds from Australia would have been the first to be taken to Europe, this is not the case. The species now known as the Magnificent Riflebird occurs in northern Queensland but also in many parts of New Guinea, and it was birds that were collected in New Guinea that first came to the attention of European scholars. Several trade skins preserved by Papuan natives arrived in London and Paris during the last years of the eighteenth century, and a painting of one of them still exists. The artist is unknown, but the picture is in a portfolio, now in the Natural History Museum in London, that was assembled by the ornithological writer John Latham.

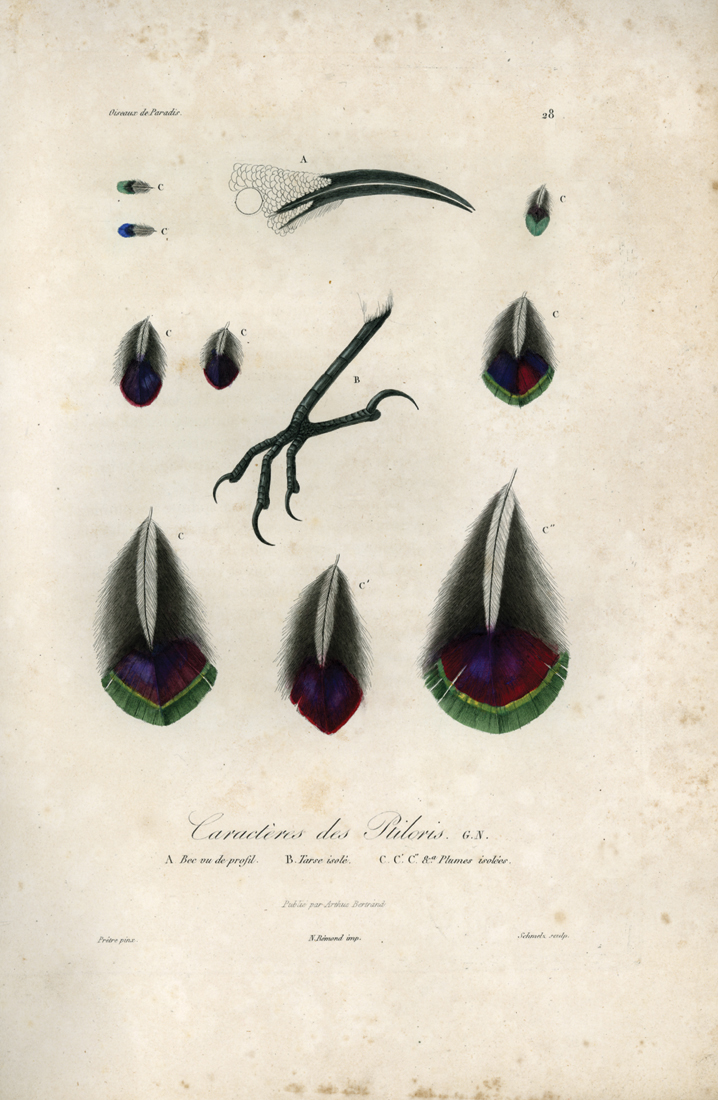

Another specimen – perhaps even the same one – served as a model for one of Jacques Barraband’s paintings. An engraving copied from this watercolour was published during the first decade of the nineteenth century, but, surprisingly, it wasn’t until 1819 that anyone thought to give the species a scientific name. It is now known as Ptiloris magnificus. Ptiloris has a curious and perhaps slightly inappropriate meaning – feathered nose. The name magnificus is more fitting, for this is certainly the largest and arguably the most magnificent of the riflebirds.

However, its more southerly relative has an equally splendid name, Ptiloris paradiseus – the Paradise Riflebird. Similar in overall appearance, it is only slightly more modestly feathered. It occurs in parts of eastern Australia that are now very familiar (from Rockhampton in the north to Newcastle in the south), but it was not described until 1825. Although the eastern coastal regions of Australia began to be settled from 1790 onwards, the hills now known as the Great Dividing Range, just 80 km (50 miles) or so inland, presented an almost impenetrable barrier to the colonists. Attempts to cross or explore it ran into all manner of problems, and those who participated endured great hardships despite being only a few kilometres from settlements. Much of the land has now been opened up, of course, but the difficulty of the terrain during those early years of settlement is undoubtedly the reason for the comparatively late discovery of the Paradise Riflebird.

Two of the earliest paintings of male Magnificent Riflebirds.

Jacques Barraband, c.1800. Watercolour, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

Anonymous, c.1790. Watercolour, 21 cm × 20 cm (8½ in × 8 in). The Natural History Museum, London (The Latham Collection).

It is now one of the better-known birds of paradise and its habits have all been fairly comprehensively studied. Even the nest is well known, which is certainly not the case with many other members of the family. One peculiarity that has been discovered in this regard is that individuals of the species sometimes line their nest with snake skin!

In 1849 John Gould, newly established as a publisher, decided to embark for Australia to collect birds – for the first and last time in his career – as reference for a forthcoming book. In northern Queensland, he discovered a third species of riflebird. Small in size, it is common within the restricted area it inhabits and in most respects is similar to the Paradise Riflebird, which is widespread further south. Gould named it Ptiloris victoriae, Queen Victoria’s Riflebird, so starting the trend, which subsequently became so widespread among those describing bird of paradise species, for naming their discoveries after royalty.

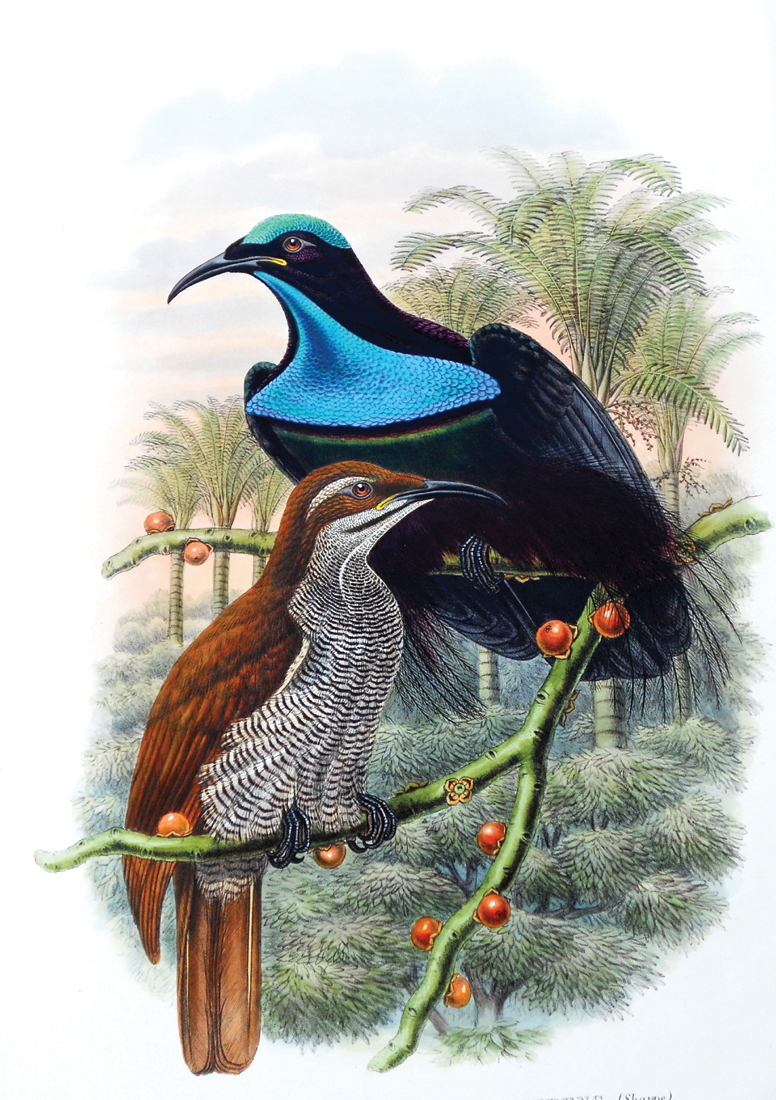

Magnificent Riflebird, male and female. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

Riflebird feathers, plus beak and foot. Coloured engraving by Jean-Gabriel Prêtre from René Lesson’s Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux de Paradis et des Epimaques (1834–35).

Riflebird plumage is not obviously spectacular. An ornithological artist, faced with a museum specimen, would not see a need to invent a particularly dramatic display, as some certainly did when trying to divine the display postures of other birds of paradise. A riflebird male has no particularly curious plumes as the males of so many species have, and the flank plumes it does possess are comparatively modest, with its beautiful breast shield conforming to a farly standard formula. So, judging from nineteenth-century illustrations, such as those by Barraband, Gould, Wolf or anyone else, the male riflebird is a conservative and undemonstrative creature. Nothing could be farther from the truth. He manages to create his spectacular effects with wings that anatomically appear to have no other function than to fly.

Queen Victoria’s Riflebird, male and female. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

Paradise Riflebird, male and female. W. T. Cooper, c.1968. Watercolour, 45 cm × 33 cm (18 in × 13 in). This painting was produced to illustrate Cooper’s first book, A Portfolio of Australian Birds (1968). Private collection.

Queen Victoria’s Riflebird, studies of a male in various stages of display. W. T. Cooper, c.1976. Pencil and watercolour. 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

A male Victoria’s Riflebird, standing on his stump or on a horizontal branch higher in the canopy, begins his performance by suddenly jerking his body erect and opening his beak to expose its brilliant yellow gape. It is a sure sign that a female is nearby. With an explosive jerk, he opens his black wings and holds them as wide apart as he can. Slowly, he raises and lowers himself, bending and straightening his legs like an exercising athlete. As the female moves around in the nearby vegetation, he swivels on his perch to keep facing her so that she always sees him at his most impressive. His wings are now extended and expanded so extremely that they almost meet over his head and he appears to have transformed himself into a looming black disc. By now the female may be so intrigued that she flies towards him and lands beside him on his stump. His ecstasy mounts and he leans backwards, almost quivering with the muscular strain involved. Then, if she remains, he lowers one wing, simultaneously raising the other to its utmost extent and hiding his head behind it. If she is still there, he begins to alternate the position of his wings, lowering one and raising the other with such force that the lower hits the upper with an audible thump. At the same time, he bends his neck from side to side so that his head remains hidden behind whichever wing is uppermost. The switching of his wings becomes swifter and swifter. The iridescent band at the bottom of his chest flashes in the sunlight. The female moves so close to him that she is embraced by each wing alternately until finally he sways to one side rather more extremely, closes both his wings, and hops on to her back. Copulation is then achieved in a brief second.

The riflebirds may not, at first sight, be among the most spectacular members of the bird of paradise family, but few others can outdo the males in the athleticism and pumped-up virility of their displays.