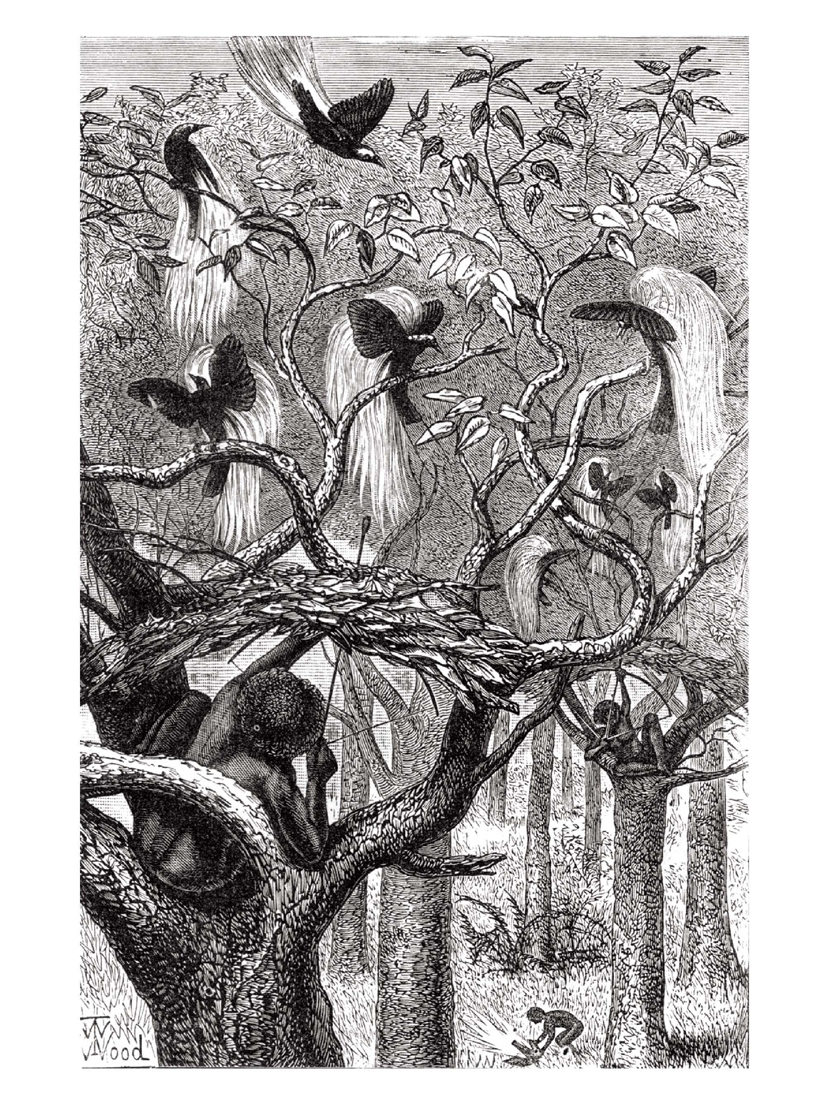

Papuans hunting the Greater Bird of Paradise on the Aru Islands. Engraving by T. W. Wood for A. R. Wallace’s celebrated book The Malay Archipelago (1869). The picture is misleading in that the plumes of the displaying birds are shown as if sprouting from above, instead of beneath the wings.

Nature seems to have taken every precaution that these, her choicest treasures, may not lose value by being too easily obtained. First we find an open, harbourless, inhospitable coast, exposed to the full swell of the Pacific Ocean; next, a rugged and mountainous country, covered with dense forests, offering in its swamps and precipices and serrated ridges an almost impassable barrier to the central regions; and lastly, a race of the most savage and ruthless character… In such a country and among such a people are found these wonderful productions of nature. In those trackless wilds do they display that exquisite beauty and that marvellous development of plumage, calculated to excite admiration and astonishment among the most civilized and most intellectual races of man…

Alfred Russel Wallace. ‘Narrative of Search after Birds of Paradise’, Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (1862).

End to the Squandering of Beauty

(Entry of the Birds of Paradise into Western Thought).

Raymond Ching, August to December, 2011.

Oils on canvas, 180 cm × 240 cm (6 ft × 8 ft).

Two or three [men of Aru, New Guinea] begged me for the twentieth time to tell them the name of my country. Then, as they could not pronounce it… they insisted I was deceiving them, that it was a name of my own invention. One old man… was… indignant. ‘Ung-lung!’ said he. ‘Who ever heard of such a name? Ang lang, that can’t be the name of your country’ Then he tried to give a convincing illustration. ‘My country is Wanumbai – anybody can say Wanumbai. But N-glung! Who ever heard of such a name? Do tell us the real name of your country… then when you are gone we shall know how to talk about you.’ The whole party remained convinced I was deceiving them. They then attacked me on another point – what all the animals and birds… were preserved so carefully for. I tried to explain… that they would be stuffed, and made to look as if alive, and people in my country would go to look at them. But this was not satisfying; in my country there must be many better things to look at… They [the Aru men] did not want to look at them [the birds]; and we, who made calico and glass and knives, and all sorts of wonderful things, could not want things from Aru to look at… The old man said to me, in a low, mysterious voice, ‘What becomes of them when you go on to the sea?’ ‘Why, they are all packed up in boxes,’ said I. ‘What did you think became of them?’ ‘They all come to life again, don’t they?’ said he… and he kept repeating, with an air of deep conviction, ‘Yes, they all come to life again, that’s what they do – they all come to life again.’

Alfred Russel Wallace. The Malay Archipelago (1869).

Arfak Six-wired Bird of Paradise. John Latham, c.1780. Watercolour (copied from an engraving by Pierre Sonnerat), 15 cm × 12 cm (6 in × 5 in). The Natural History Museum, London.

Feathers from Paradise. Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.