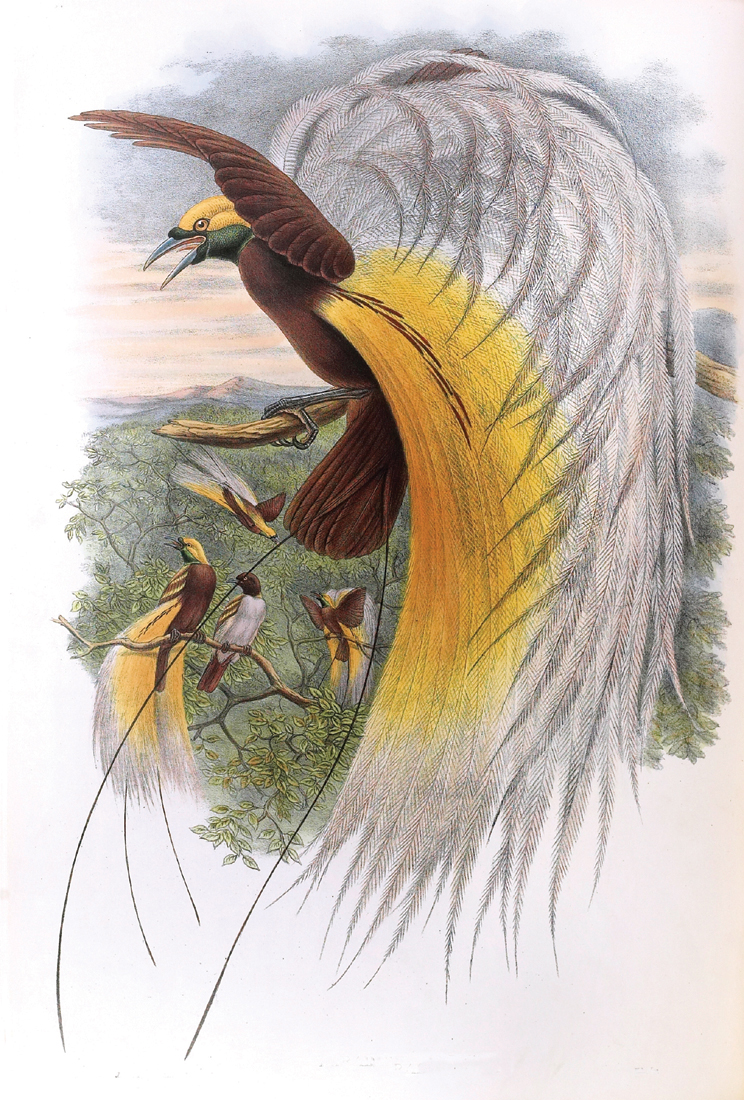

King Bird of Paradise, male. Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour. 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

To the human eye, birds are among the most beautiful and intriguing of all nature’s creations. Even a single stray feather, picked up by chance on a country walk, is a thing of wonder if examined closely. Its form, delicacy, and its colouring – sometimes subdued, sometimes gaudy – each have the power to astonish. And even the most familiar of species – the soberly dressed house sparrow or the common starling, for instance – are creatures of subtle beauty when viewed with fresh eyes.

There are, of course, whole families of birds well known for the astonishing visual impact of their plumage. Take, for example, the pheasant family. It boasts many spectacularly coloured species – the peacock, the tragopans and monals, or even the common pheasant itself – that defy description in words. Many other families contain kinds that are equally remarkable.

But one family stands out from the rest, not just because of the exquisite appearance of many of its species, but also because of the sheer extravagance of variety, colour and form that these creatures parade. These are birds that truly live up to their name: birds of paradise.

From the moment of their introduction to the European mind in the early sixteenth century, their unique beauty was recognised and commemorated in the first name that they were given; birds so beautiful must be birds from paradise! This naming extravaganza even continued into the nineteenth century when newly discovered species were named after illustrious crowned heads of Europe – Prince Rudolph’s Blue Bird of Paradise, Princess Stephanie’s Bird of Paradise, the Emperor of Germany’s Bird of Paradise. The list of royal names goes on and on. Nor were splendid names enough to satisfy the inquiring minds of those who encountered the birds. In the early days all manner of fanciful stories and theories grew up to explain the mystery of their phenomenally beautiful appearance, and the tales quickly acquired mythical status. And as far as mystery is concerned, these birds are still wrapped in enigma.

Of course, we now know much more than the European scholars of the early sixteenth century who received the first specimens from the then remote lands somewhere far to the east. But there is much that is still unknown.

A major reason for this mystery surely lies in the nature of the birds’ main homeland, the great island of New Guinea. Shrouded in exotic mystery, this island stronghold is one of the world’s last truly wild places. Its jungle-covered mountain ranges and steamy, tangled lowlands provide some of the most formidable and daunting of terrains. Add to this the ferocious reputation of New Guinea’s inhabitants, and the island has represented something of a fortress against exploration and industrial exploitation. In the coming decades this state of affairs will doubtless change, but for the time being much of the island remains in a virtually pristine state, and many bird of paradise secrets stay intact.

Most people with an interest in ornithology will recognise the gloriously plumed Greater Bird of Paradise, but to many it comes as something of a surprise to learn that this species is not alone. In fact, more than 40 distinct species are currently recognised. Among these are quite astounding differences in size, shape and colour patterning. The tiny King Bird of Paradise, for instance, with its exquisite red plumage, metallic green breast band and peculiar curled ends to the tail feathers (which are otherwise no more than naked quills), seems to have little in common with the metre-long Black Sicklebill sporting a shimmering tail and long, slender, down-curved beak. Yet all the species are bound together by underlying structural affinities.

King Bird of Paradise, male. Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour. 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

Two male Black Sicklebills with a female. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

Two species of plume bird, both males. Watercolours by Jacques Barraband, c.1802, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Lesser Bird of Paradise. Red Bird of Paradise. Private collection.

These similarities are much more apparent in the females of the various species. Often these soberly plumaged birds (it is only the males of each species that are spectacularly adorned) are remarkably alike, even though their respective males look so very different.

The species generally referred to as plume birds are the ones that conform in appearance to general expectations. Characterised by great bunches of lace-like flank plumes coloured variously yellow, red, white or even blue, it is these species that provide the basis for the iconic images of birds of paradise that grace all manner of postage stamps and advertising campaigns.

The national airline of Papua New Guinea carries a plume bird as its logo, and advertisements for the country or its products rarely – if ever – appear without one. In fact, New Guinea is characterised by the image of the bird of paradise. Its national sport may be rugby league, its cultural heritage may be summed up in the dramatic masks and tribal artefacts made by the indigenous peoples, its image often reduced to photographs of tribesmen in spectacular costumes, but its most widely known residents are birds of paradise.

That this family of birds has always exerted a hold over the minds of humans is shown by the manner in which the peoples of New Guinea have prized them from time immemorial. Indeed, the very nature of their tribal customs is defined by the extravagant use of, and trade in, bird of paradise feathers.

Curiously, the production of ethnographical artefacts and works of art hardly reflects this great cultural interest – in traditional New Guinea tribal art there is little or nothing that uses the bird of paradise motif, at least in terms of sculpture or painting. It is a well-worn idea that art is often the product of the need to possess. An artist may paint a bird, a flower, a woman, a view, because he or she wants to own that image, to possess it. New Guinea tribesmen did, of course, own the actual birds themselves. Why would they need the help of art to facilitate that urge? They possessed the birds quite literally, and adorned themselves in the most fantastic ways with the feathers. Nor were they oblivious to the fundamental purpose of this extravagant ornamentation. When a New Guinea tribesman arrayed himself with gorgeous plumes and feathers, and danced, he too was displaying and advertising his sexual desirability.

Queen Carola’s Six-wired Bird of Paradise. Detail from a watercolour by William T. Cooper, c.1976.

King Bird of Paradise. Detail from a hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Magnificent Bird of Paradise. Detail from a watercolour by William T. Cooper, 1976.

The Five Senses and the Four Elements – an early representation of a Greater Bird of Paradise, painted using an imported dried skin as a model. Though seemingly wingless and legless, it is propelling itself through the open window – perhaps returning to paradise! Jacques Linard, 1627. Oils on canvas, 103 cm × 150 cm (41 in × 60 in). Musée des Beaux-Arts, Algiers.

Paint and Plumes. Errol Fuller, 2012. Oils on panel, 46 cm × 66 cm (18 in × 26 in). Private collection.

Once these same feathers reached the western world their impact was immediate. Here it manifested itself through art and fantastical stories and myths, while princes and emperors displayed power and taste by acquiring the rarely imported specimens for their cabinets of curiosities and museums. The impact may indeed have taken a more veiled, symbolised, form, but it was still profound and eventually led to a manner of human adornment strangely parallel to that shown among New Guinea peoples. Through the nineteenth century and on into the first decades of the twentieth, it was the very height of fashion to add the most bizarre concoctions of feathers as appendages to finely crafted hats and clothes. But this time it wasn’t the males who were displaying their loveliness; it was the most fashionable of ladies!

In 1522 the first of many, many bird of paradise plumes arrived in Europe. Within just months they had attracted the attention of a celebrated artist, Hans Baldung Grien. His picture may be a comparatively flimsy affair, but it began a tradition among artists that continues to this day. The list of artists who have felt compelled to draw or paint birds of paradise is studded with some illustrious names: Brueghel, Rubens, Rembrandt, Millais. Then there are men who actually specialised in painting birds: Barraband, Wolf, Hart, Gould, Keulemans. And, of course, there are modern painters. Walter Weber produced a series of iconic images for The National Geographic Magazine during the early 1950s, William T. Cooper illustrated two major monographs on birds of paradise, and Raymond Ching is known throughout the world for his poetic and highly charged paintings.

Greater Bird of Paradise. Charles R. Knight. Oils on panel, size, date and whereabouts unknown. Copyright Rhoda Knight Kalt.

It is an inevitable consequence of a book that attempts to trace the history of these birds through their appearance in art, that the work of these few men will feature to what may seem a disproportionate degree. Many people have painted birds of paradise, but only a few have produced work that is worthy of particular attention, or has significantly added to the body of work that went before them. One reason for this (and it applies almost as much today as it did in past times) is that these birds are difficult to see. In days gone by it was virtually impossible, but even in the twenty-first century it is by no means easy. They rarely occur in zoos or aviaries, and a trip to New Guinea – daunting in itself – will not necessarily lead to seeing birds in ways that are helpful to the artist. Another reason is that these are extraordinarily difficult birds to capture in paint or pencil, even if good views are obtained. They do not always conform to the shapes that more familiar birds adopt, and making sense of the extravagant ornamental plumage – the metallic breast shields and throat gorgets, the axe-shaped feather fans, the lace-like plumes – is not an easy exercise.

Male Lesser Birds of Paradise with a female. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart and John Gould from Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88).

Eleven bird of paradise species from five distinct genera that lack the more extravagent features usually associated with the family.

(Top row, from left). Paradise Crow (Lycocorax pyrrhopterus); Glossy-mantled Manucode (Manucodia ater); Long-tailed Paradigalla (Paradigalla carunculata); Crinkle-collared Manucode (Manucodia chalybata). All images except Paradigalla hand-coloured lithographs by W. Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98). Paradigalla, watercolour by Lilian Medland from Tom Iredale’s Birds of Paradise and Bower Birds (1950).

(Middle row, from left). Short-tailed Paradigalla (Paradigalla brevicauda), hand-coloured lithograph by H. Gronvold from Ibis (1912); Sickle-crested Bird of Paradise (Cnemophilus macgregorii); Curl-crested Manucode (Manucodia comrii), both images hand-coloured lithographs by W. Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

(Bottom row, from left). Loria’s Bird of Paradise (Cnemophilus loriae); Wattle-billed Bird of Paradise (Loboparadisea sericea); Jobi Manucode (Manucodia jobiensis); Trumpet Bird (Manucodia keraudrenii). All images except Jobi Manucode hand-coloured lithographs by W. Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98). Jobi Manucode, watercolour by Lilian Medland from Tom Iredale’s Birds of Paradise and Bower Birds (1950).

This book is not a complete cultural history of the birds of paradise and their effect on man. It is focused very much through western eyes. The matter of the birds’ influence on, and importance to, the peoples of New Guinea is only touched on: that is a subject for another book.

Nor does it include photographs, despite the fact that in recent years many wonderful images have been captured by camera. Photography, however, is beyond the scope of the present work, although it would make a splendid subject for another.

The book is certainly not intended as a complete monograph of the Paradiseidae, with each species described in detail. It is more in the nature of a tour through art and history with a good deal of ornithology thrown in. Its central idea is to showcase the breathtaking beauty of these birds and the enormous interest that surrounds them. As it is something of a historical ramble, the chapters are ordered according to the sequence in which the birds representing the various genera made their appearance in Europe.

According to generally accepted opinion, the species currently recognised are divided into sixteen genera, but only eleven of these genera are featured here in detail. The other five contain species – eleven of them – that are less visually spectacular and have histories that are, perhaps, less absorbing. They represent earlier stages in the evolutionary history of the bird of paradise family before the males abandoned their parental duties to devote themselves to the sexual displays that now dominate their lives and made them creatures of such extraordinary and extravagant beauty.