After the cancellation of the Batman TV series in 1968, the character basically disappeared from view as far as the general public was concerned. The camp craze that surrounded Batman came to an abrupt end, and all of the “POWs,” “BAMs” and “ZAPs” that went along with it faded from the national spotlight. However, the years immediately following the show’s demise were incredibly eventful ones for the Batman of the comic books. DC Comics was left with a commodity that to the majority of the general public appeared to be washed up—but to many comic book fans, Batman remained a treasured icon. So in an ironic twist, the end of the TV series and Batman’s widespread popularity would end up leading to a major revitalization of the character.

But before we start examining that revitalization in detail, we need to back up just a bit and look at what was happening in the world of Batman comics during the last half of the Batman TV series’ three-year run. In 1967, Batman’s premier New Look artist Carmine Infantino was promoted to editorial director of DC Comics. Since Infantino’s modernized visual interpretation of Batman did not jibe with Bob Kane’s “old school” approach, Kane found himself increasingly at odds with DC over the character he had created. But as we have noted earlier in this book, even though Kane had received sole credit for the creation of the Batman character, Kane’s Batman comic art had almost always been a collaborative effort. Indeed, Kane had begun hiring uncredited ghost artists to help him illustrate Batman stories within the first few months of the character’s existence. Since the efforts of so many individual artists were responsible for making Batman into the icon he had become, it was probably inevitable that Kane’s influence regarding the character’s development would eventually wane to nothing.

This fact obviously did not sit well with Kane. There is no doubt that he loved all of the limelight and financial gain he received for being Batman’s sole creator—and he was content to enjoy those spoils while basically doing none of the day-to-day work required to create the Batman comic art that bore his name. But by the mid–1960s, Kane certainly had to see the handwriting on the wall. His character had evolved to a point where he would never have any significant control over it again, and DC was starting to make sure that the writers and artists who were creating new Batman comic stories would be publicly credited for their work—the era of Kane’s ghost artists doing all the work and Kane getting all the credit was over.

It is sad to note that after doing so little and receiving so much, Kane’s final years at DC were marked by him brazenly asserting that he deserved even more creative credit for Batman than he had been given. The most glaring example of Kane’s selfishness relating to the Batman character occurred in September 1965, when he wrote an open letter to a Batman fanzine called Batmania. Kane wrote the letter in order to respond to public comments made by Bill Finger earlier that year—in these comments, Finger had stated that he was far more involved in the creation of the Batman character than he had ever been given credit for. Kane was furious over Finger’s claim that he was as responsible for the existence of Batman as Kane was.

Kane’s long letter to Batmania is fascinating to read, because in vociferously defending himself against Finger’s claim, he basically resorts to telling out-and-out lies about how involved he was in the creation of Batman comics during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. In the letter, Kane states that in the “Golden Age” of the character, he penciled, inked and lettered the strip himself. He goes on to claim that ninety percent of the mid–1960s New Look Batman stories were drawn by him as well. Obviously, these were outrageously false assertions—earlier in this book, we have examined a number of artists who ghosted for Kane during this time period such as Jerry Robinson, Dick Sprang, and Sheldon Moldoff. In the letter, Kane even accidentally reveals how totally disconnected he had become from the Batman character by the mid–1960s—for example, at one point he refers to the 1950s Batwoman character as one of his “villains.”1

In fairness to Kane, he still made a point of recognizing Finger’s valuable contributions to the development of the Batman character in his letter. But this small gesture of goodwill does not make up for the fact that he was willing to be so deceitful in order to portray himself as the sole architect of Batman’s continuing success. In short, Kane certainly deserved credit for creating Batman, perhaps even sole credit because he was the one who initially undertook the task to create a new costumed comic hero in the wake of Superman’s success. That said, however, the untruths Kane was willing to put forth regarding his ongoing involvement in Batman comics, untruths like the ones found in this letter, will always stand as a mark against his personal character. Incidentally, Batmania might very well have been uncomfortable with the amount of shameless self-interest found Kane’s letter—they chose not to publish it in the fanzine until 1967. By that time, it was obvious that Kane’s efforts to retain control of the Batman character would not succeed. Kane retired from DC and regular Batman comic work that same year, not long after Infantino’s promotion to editorial director.2

Even though Kane would no longer be a part of Batman’s ongoing development at DC, he would continue to enjoy the spoils of being recognized as the character’s sole creator. The income he had earned through Batman comics and the 1960s Batman screen projects made him a wealthy man. And the staggering success of the 1960s screen Batman also brought him a certain degree of celebrity. Kane’s Batman fortune and fame would continue to grow over the years, reaching its zenith in 1989—that year, he would get the opportunity to be a focal point of the Batmania surrounding the character’s fiftieth anniversary and the release of the 1989 film Batman. (We’ll discuss Kane’s involvement with the Warner Bros. Studios Batman film series later in the book.)

There is another point I feel I need to make before we completely leave the era of the 1960s camp Batman behind. As I mentioned at the end of the last chapter, there are a substantial number of Batman fans that feel the 1960s Batman TV series and film are insults to the character because they chose to play Batman for laughs. These fans feel much the same way about the Batman comic stories of the late 1960s, because during this time DC basically hopped on the camp bandwagon and created stories featuring the character that had the look and feel of the Batman TV show. But I find it fascinating to note that even during the camp Batman’s peak period, Batman was still Batman—in other words, he never lost his uniqueness or his timeless appeal.

To illustrate this point, please allow me a moment to recap one of my favorite Batman comic stories of all time. “Hunt for a Robin-Killer” was first published in Detective Comics #374, April 1968. The story was written by Gardner Fox, penciled by Gil Kane and inked by Sid Greene. The story is not one that is considered “great” by most Batman comic fans—in fact, it never has been reprinted in any sort of “Best of Batman” anthology released by DC Comics. But it has remained a personal favorite of mine because it presented such a compelling depiction of Batman as a crimefighter and detective.

“Hunt for a Robin-Killer” tells the tale of Batman tracking down a vicious criminal named Jim Condors after Condors brutally beats Robin almost to death. At the opening of the story, Batman and Robin are raiding the hideout of a gang of criminals. During the raid, Condors makes a sneak attack on the Boy Wonder while Batman is occupied taking down the gang. (Condors holds a grudge against Robin because the young hero apprehended Condors’s brother during a solo case.) Batman finds Robin, bloodied, bruised, and perilously close to death, and rushes the boy to a nearby hospital. Overcome with grief, Batman then goes on a manhunt to find the criminal who had come so close to killing his junior partner. Batman has a hard time keeping his feelings of rage and vengeance under control during this intensely personal case, but in the end he uses his superior detection skills to find Condors and bring him to justice. The story ends with Robin being released from the hospital, still weak, but ready to take his place alongside his mentor.

“Hunt for a Robin-Killer” is a well-written, realistic crime drama that features Batman and Robin fighting non-costumed thugs similar to characters one might find in a 1940s film noir production. And Kane and Greene’s art is every bit as strong as Fox’s story—their work features unusual panel layouts, deep perspective, and wonderfully realistic, expressive characters. Fox, Kane and Greene perfectly capture the essence of Batman and his world in “Hunt for a Robin-Killer.” In the tale, Batman descends on criminals with a vengeance that fills them with terror. At one point, he even appears in menacing silhouette in a doorway, a dark vigilante bent on apprehending Robin’s attacker. “Hunt for a Robin-Killer” depicted Batman in a manner not that far removed from the character’s late 1930s–early 1940s adventures—and it hit the newsstands just as the Batman TV series was airing the last of its third season episodes! To me, the story stands as proof that all of the camp silliness that the 1960s Batman craze delivered did nothing to lessen the power of the Batman character.

And that power was about to grow even stronger with the cancellation of the Batman TV series. Free from the masses who enjoyed regarding Batman as a silly, throwaway piece of pop culture, DC Comics decided to let a new breed of comic book writers and artists return the character to his dark late 1930s roots. This new era in Batman comic history began with a story that appeared in Batman #217, December 1969, entitled “One Bullet Too Many.” The story was written by Frank Robbins, penciled by Irv Novick and inked by Dick Giordano. In “One Bullet Too Many,” Dick Grayson moves out of Wayne Manor in order to attend college at Hudson University outside of Gotham City—obviously, this means the end of Batman and Robin working regularly together as a team. Bruce Wayne decides that this major change in his life should bring about major changes in Batman’s career as well—Batman will once again become a mysterious figure who prowls the night as a lone vigilante.

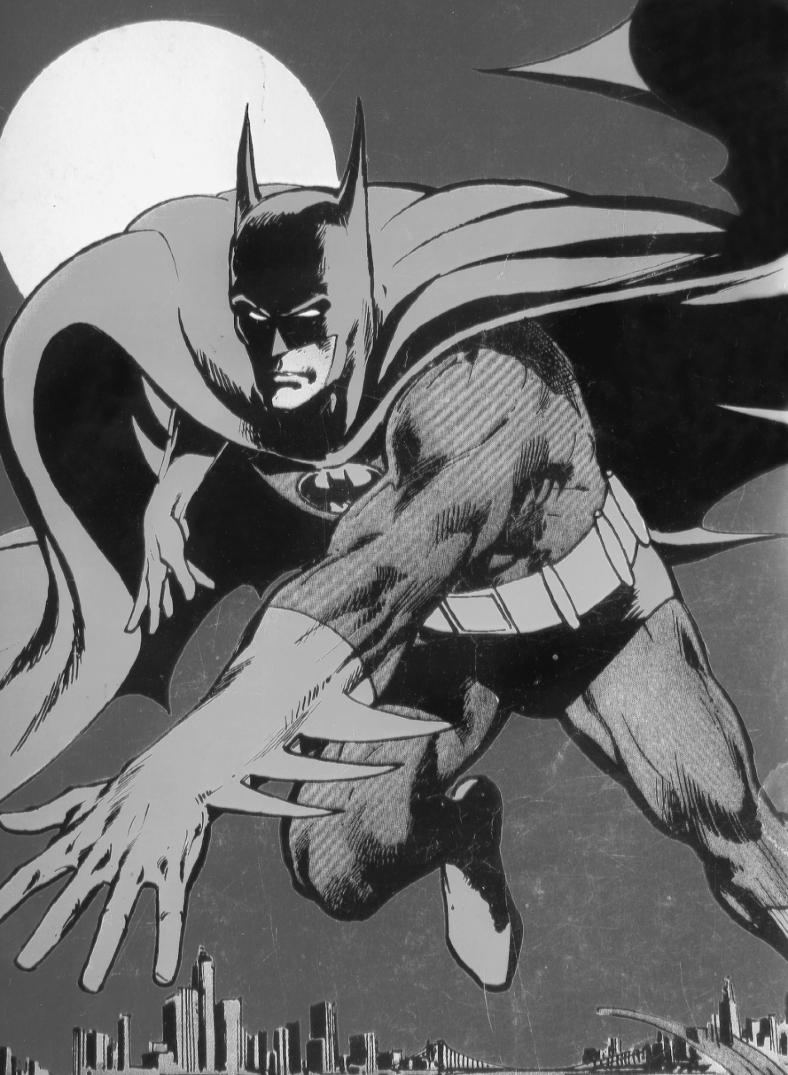

Batman in 1974, returned to his dark roots. Art by Neal Adams.

Writer Denny O’Neil and artist Neal Adams were the most notable storytellers in this new era of Batman comics; their first Batman collaboration was the story “The Secret of the Waiting Graves” published in Detective Comics #395, January 1970. In the tale, they depicted Batman as a grim detective whose costume featured the long ears, angular cowl and dramatically flowing cape of Bob Kane’s and Bill Finger’s original vision. In “The Secret of the Waiting Graves,” Batman travels to Mexico and encounters a wealthy couple by the name of Muerto that have discovered a rare kind of flower which has the power of conferring immortality on anyone who regularly smells its fragrance. But the fragrance also drives anyone who smells it long enough completely mad, so Batman decides to destroy all of the flowers. After he does so, the Muertos age over a century in just the matter of a few seconds and fall over dead. “The Secret of the Waiting Graves” ends with Batman standing over the Muertos’ fresh graves, a grim expression on his face. O’Neil’s dark, emotionally complex script and Adams’ intricate figural renderings made the story’s Batman seem far more realistic than any previous version of the character had been. But at the same time, the supernatural forces he faced in the tale also gave him a mysterious, horror movie–type of quality.

Comic book fans immediately embraced the O’Neil-Adams version of Batman. Throughout the first half of the 1970s, they created a host of tales featured in Batman and Detective Comics that were hailed as Batman classics from the moment they were released. Their story “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge!,” published in Batman #251, September 1973, was especially important, because in it they returned the Joker from the silly prankster he had become in 1950s and 1960s comics to the leering, homicidal madman found in Kane and Finger’s original work.

In “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge!” the villain is ruthlessly hunting down members of his old gang because one of them betrayed him to Batman and the Gotham Police, leading to his arrest. The Joker kills his former henchmen one by one, with Batman hot on his trail. Batman finally catches up to the Joker at a seaside aquarium that has been closed due to a recent oil spill. The Caped Crusader manages to save the Joker’s last surviving henchman just as the villain throws the henchman into a tank containing a ravenous shark. Batman then chases the Joker down on the oil-slicked beach, bringing him to justice with several savage punches. “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge!” delivered the first modern age view of a dark hero in cape and cowl battling a murderous, mirthless clown in a moody, film noir–like setting. In other words, it virtually provided a blueprint for all of the classic Batman/Joker confrontations that would follow in the coming decades.

O’Neil and Adams were also responsible for creating one of Batman’s all-time greatest comic book foes, Ra’s Al Ghul. Ra’s appeared to be a middle-aged man of far eastern descent who was in possession of great wisdom and strength—but basic appearances could not begin to scratch the surface of his real history. Thousands of years old, Ra’s Al Ghul was able to rejuvenate himself in a bubbling cauldron of chemicals known at the Lazarus Pit. Ra’s felt that the planet was on the verge of being destroyed by the reckless actions of twentieth century humankind, so he wanted to wipe out most everyone on Earth in order to restore the planet to what he considered to be its “natural balance.” Obviously, Batman opposed Ra’s’ plan to purge the planet of most of its humans, but his relationship with the villain was far more complex than a standard “good guy vs. bad guy” scenario.

Batman first met Ra’s Al Ghul in “Daughter of the Demon,” a story published in Batman #232, June 1971. Right from the first panels, it was obvious that Ra’s was going to be unlike any other villain Batman had ever faced. In the story, Batman learns that Robin has been kidnapped and is being held prisoner by an unknown criminal. (Even though Dick Grayson had been sent off to college, Robin still made occasional appearances with Batman in Batman comic titles.) Just as Batman begins to investigate his partner’s abduction, Ra’s steps out of the shadows of the Batcave and tells the crimefighter that he has deduced his secret identity. Ra’s also reveals that his beautiful daughter Talia, whom Batman had met on an earlier case, has been kidnapped in a similar manner. Ra’s proposes that they work together to rescue Robin and Talia.

Clues left by the kidnappers lead Ra’s and Batman to the hideout of an organization known as the Brotherhood of the Demon, located high in the Himalayan Mountains. But by the time he reaches the hideout, Batman has deduced that the person behind Robin and Talia’s abduction is none other than Ra’s himself. When Batman confronts Ra’s with this information, Ra’s admits it is true that he staged the entire scenario. Ra’s then reveals why he went to all this trouble. Talia is in love with Batman, and Ra’s wants to retire from running his criminal organization—so he set up a test to see if Batman was worthy of becoming his son-in-law and heir! Ra’s informs Batman that he has passed this test, and the story ends with Talia kissing the stunned crimefighter on the cheek.

Needless to say, Batman did not take Ra’s and Talia up on their offers. In fact, over the years he worked to thwart a number of Ra’s’ schemes to wipe out most of the people on Earth. But opposing Ra’s did not keep Batman from having feelings for Talia—he was captivated by her beauty and spirit, even though she was in his eyes every bit as much of a criminal as Ra’s himself. And opposing Batman did not keep Ra’s from having feelings for his enemy—Ra’s kept Batman’s secret identity a secret in the hopes that the crimefighter would one day change his mind about joining his organization and marrying his daughter. In other words, though Batman and Ra’s were mortal enemies, there were deep psychological connections between them that almost bordered on a familial relationship. These connections helped to make some of Batman’s battles against Ra’s Al Ghul among the best Batman comic stories ever published.

While Neal Adams’ Batman art is often given the majority of the credit for visually returning the character to his “creature of the night” roots, there were a number of other talented artists who produced equally memorable Batman images during the 1970s. Dick Giordano not only inked a substantial amount of Adams’ Batman art, but he also was the main illustrator of many excellent Batman stories featured in Batman and Detective Comics. (Just a few pages back, we noted Giordano’s inking efforts on the story which began this new era in Batman comic history, “One Bullet Too Many.”) Also, Jim Aparo’s excellent Batman renderings, which featured the realism of Adams’ style coupled with the strong lines of more traditional comic artwork, were a welcome fixture of countless stories featured in The Brave and the Bold and Detective Comics. Aparo’s close association with the character continued well into the late 1990s, making him one of the most prolific Batman artists of all time.

As Batman’s comic book world began to grow darker and more sophisticated, the first-ever reference books designed for serious Batman fans were published. The 1971 anthology book Batman from the 30s to the 70s contained classic Batman comic stories ranging from his 1939 debut all the way up to O’Neil-Adams works such as “The Secret of the Waiting Graves.” And the 1976 book The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes Volume 1: Batman by Michael J. Fleisher provided a wealth of information on the thousands of characters appearing in Batman comic stories between 1939 and 1965. Unfortunately, while that book was very comprehensive, its focus was too narrow—it made no attempt to cover all of the changes the character had gone through during the camp Batman craze of the 1960s and the O’Neil-Adams led revamp of the 1970s.

Batman’s comic book world might have been growing more serious during the 1970s, but the character’s lighthearted 1960s screen works kept right on winning new fans. Since youngsters were still being drawn to this incarnation of Batman, the character was featured in a variety of kiddie television cartoon series from the late 1960s all the way up to the 1980s.

The first of these series was Filmation’s The Batman-Superman Hour, which first aired on CBS in late 1968 and early 1969. Contrary to the program’s name, Batman and Superman never appeared together—they each starred in their own cartoon adventures. Batman’s cartoons in the series were very similar in tone to the third season of the live-action Batman TV series—they featured Robin and Batgirl working with the Caped Crusader, battling familiar villains such as the Joker, Penguin, Riddler and Catwoman. In 1969, CBS repackaged The Batman-Superman Hour’s Batman cartoons into a Batman-only series entitled Batman with Robin the Boy Wonder. Like so many Saturday morning kiddie cartoons, Filmation’s 1968–69 Batman cartoons were of decidedly poor quality—their animation was very cheaply produced, and their scripts were unbearably silly. In the cartoons, the part of Batman was voiced by Olan Soule and the part of Robin was voiced by Casey Kasem.

Filmation’s next series of Batman cartoons, The New Adventures of Batman, was no better. The New Adventures of Batman first aired in 1977 on CBS, and it too was burdened with terrible production values. To make matters worse, Filmation decided to add a new character to the series—Bat-Mite! (As discussed in Chapter 5, Bat-Mite was an interdimensional imp in an ill-fitting Batman costume who appeared in Batman comic stories of the late 1950s and early 1960s.) The New Adventures of Batman was already bad enough due to its poor animation and stories, but adding one of the silliest regular characters ever to appear in the pages of Batman comics made them doubly awful. Incidentally, Adam West and Burt Ward provided the voices for Batman and Robin in The New Adventures of Batman, but not even the presence of the legendary screen Caped Crusaders of the 1960s could help to salvage the series.

The longest-running television cartoon program to feature Batman was the Hanna-Barbera series Super Friends, which premiered on ABC in 1973. The Super Friends were a team of DC heroes similar to the one found in the DC comic title Justice League of America. The team included Superman, Batman, Robin, Wonder Woman and Aquaman, as well as a variety of other heroes that appeared as occasional guest stars. The Super Friends series ran on ABC under slightly varying titles (The All-New Super Friends Hour, Challenge of the Super Friends and The World’s Greatest Super Friends) until 1979. In all of these versions of Super Friends, the part of Batman was voiced by Olan Soule and the part of Robin was voiced by Casey Kasem, reprising their roles from the 1968–69 Filmation Batman cartoons.

The series was revived by Hanna-Barbera and ABC in 1984 under the title Super Friends: The Legendary Super Powers Show, and in 1985 under the title Super Powers Team: The Galactic Guardians. As he had for 1977’s The New Adventures of Batman, Adam West provided Batman’s voice in Super Friends: The Legendary Super Powers Show and Super Powers Team: The Galactic Guardians. In these Super Friends incarnations, the part of Robin was again played by Casey Kasem.

Like Filmation’s Batman cartoons, the 1970s incarnations of Super Friends were by no means “high-class” productions—they featured lackluster animation and stories designed for very young audiences. The 1980s SuperFriends were far more ambitious than their predecessors, especially in terms of their scripts, presenting stories that thoughtfully adapted some of DC’s most cherished comic book traditions.

For example, an October 1985 episode of Super Powers Team: The Galactic Guardians entitled “The Fear” depicted Batman’s origin on screen for the very first time. The episode was written by Alan Burnett, who would go on to co-produce the landmark animated television series Batman: The Animated Series in the early 1990s. In “The Fear,” Batman faces one of his longtime comic book foes, the Scarecrow, who dresses up like his namesake and is obsessed with inflicting fear on his victims. While chasing the Scarecrow, Batman inadvertently runs into the Gotham City alley where his parents were killed. The crimefighter is paralyzed with fright after memories of his parents’ murders come flooding back to him. Batman realizes that in order to defeat the Scarecrow, he must overcome his fears surrounding his parents’ deaths; he does just that, and the Scarecrow is captured at the end of the episode.

When surveying the history of the Batman character’s screen appearances, “The Fear” stands out as sort of a “missing link.” The episode bridged the gap between the campy, kiddie-oriented screen Batman found in the 1960s Batman TV series and film, and the darker, more emotionally complex screen Batman found in the Warner Bros. live-action Batman films. For the first time, Batman was brought to the screen as a character that was unequivocally scarred by deep personal tragedy. It is interesting to note that this first glimpse of a serious screen Batman featured none other than Adam West voicing the character! Ironically, the actor who was the icon of the 1960s camp Batman craze helped to usher in the era of a darker screen Batman.

Still, with the exception of “The Fear,” most of Batman’s cartoon appearances from the 1960s up through the 1980s were decidedly “kiddie” in nature. And since Batman was a character that appealed mainly to children during this time period, there was no shortage of Batman toys being produced. The most notable of these toys were the line of Batman action figures and accessories made by the Mego Company in the 1970s. Mego manufactured a line of 8" figures billed as “The World’s Greatest Superheroes” which included Batman, Robin and Batgirl, as well as the villains the Joker, Penguin, Riddler and Catwoman.

The plastic figures themselves were outfitted in wonderfully detailed cloth costumes. Along with these figures, Mego offered accessories such as the Batmobile, the Batcycle and the Batcopter, as well as a large Batcave playset. All of Mego’s Batman toys tended to reflect the look of the 1960s New Look comic stories, as well as the 1960s Batman TV show and film. For the first time, a large part of the Batman mythos had been realized in miniature form by one specific toymaker. By collecting Mego Batman toys, children could bring Batman’s world to dazzling three-dimensional life right in their own homes.

Now, back to the world of Batman comics. While not as prolific as comic creators like O’Neil, Adams, Giordano or Aparo, writer Steve Englehart and artists Marshall Rogers and Terry Austin made a tremendous impact on the Batman character with a series of stories that appeared in Detective Comics from August 1977 through April 1978. These stories featured familiar allies such as Robin, Alfred and Commissioner Gordon, and familiar villains like the Joker and the Penguin, but several new Englehart characters thrown into the mix added a narrative depth not often found in comic books of the time.

One of these characters was Silver St. Cloud, a successful businesswoman with whom Bruce Wayne fell in love, and during the course of their romance she deduced that he was actually Batman. Another was Rupert Thorne, the corrupt President of Gotham City Council, who tried to stop Batman from interfering with his criminal activities by falsely accusing the Caped Crusader of being an outlaw. Englehart also resurrected a Batman villain that had not appeared in Batman comic stories since the early 1940s—Hugo Strange was an evil scientific genius whose criminal schemes accidentally led him to discover that Bruce Wayne was actually Batman. (In Englehart’s stories, Batman had a much harder time than usual keeping his identity a secret!) Englehart’s storytelling in these comics, a mixture of adventure, intrigue and romance featuring characters old and new, was so sophisticated that many readers considered his Batman to be the “definitive” depiction of the character.

Englehart’s stories were made all the more compelling when coupled with the art of Rogers and Austin. While similar to the art of Neal Adams, Rogers and Austin’s work rendered Batman and his world in a more strongly linear, almost architectural fashion. This style perfectly suited Englehart’s complex plots, and made Batman seem closer to the “real” world than ever before.

The climax of the Englehart-Rogers-Austin Batman saga was a two-part Joker story that ended with Batman battling his arch nemesis high atop an unfinished skyscraper in a fierce thunderstorm. A bolt of lightning sends the Joker tumbling off of a girder to his apparent doom. (But as all Batman fans know, he’ll find a way to survive and torment our hero yet again as he has many times before.) Just at this moment of triumph, Batman is handed a tremendous personal sorrow—Silver leaves him because she is unable to cope with his double life.

Englehart’s Detective Comics scripting run featured a welcome addition to the Batman mythos that is worthy of note. In his stories, Englehart referred to Batman by the nickname “The Dark Knight.” As we discussed in Chapter 1, this nickname was first used in the story “The Joker” which appeared in Batman #1, Spring 1940—but the nickname had been used very sparingly in Batman comic stories after that. Englehart’s decision to resurrect the practice of referring to Batman as “The Dark Knight” would have far-reaching implications—eventually, the phrase would become DC’s official second name for Batman.

Incidentally, the Englehart-Rogers-Austin Batman saga has remained very popular with serious Batman fans over the years, so it has been reprinted in a number of different book formats. For example, in 1999 the stories were published in a stand-alone book entitled Strange Apparitions.

The revitalization of the Batman character in 1970s comic stories, combined with the blockbuster success of the 1978 Warner Bros. motion picture Superman starring Christopher Reeve in the title role, led to the first attempts to produce a new live-action Batman screen work. In 1979, Michael Uslan and Benjamin Melniker set up a production company called BatFilm Productions to finance a Batman film that would be far more serious in tone than the 1960s TV show.3 The project was not realized at this time, but it laid the groundwork for Batman’s return to the big screen a decade later. (We’ll discuss Uslan’s and Melniker’s efforts in detail next chapter.)

Batman and Robin in “The Malay Penguin,” Detective Comics #473, November 1977. Art by Marshall Rogers and Terry Austin.

The 1960s screen Batman works had been so staggeringly successful that Uslan and Melniker certainly had their work cut out for them in terms of trying to convince the entertainment industry that a Batman screen work could be so much deeper than a silly camp romp. Ironically, this point probably could not have been made any more clearly than it was by a television production featuring Batman and Robin released the very same year that Uslan and Melniker formed BatFilm Productions. Adam West and Burt Ward reprised their roles as Batman and Robin in the 1979 NBC two-part television comedy special entitled Legends of the Super Heroes. The special was produced by Hanna-Barbera as sort of a live-action companion to their Super Friends cartoon series. Legends of the Super Heroes marked the only time that the Batman character appeared in a live-action screen production between the Batman TV show’s 1968 cancellation and the 1989 Warner Bros. motion picture Batman.

The first part of Legends of the Super Heroes was called “The Challenge,” and it featured Batman, Robin, and a host of DC heroes battling a host of DC villains who had created a bomb that was powerful enough to kill everyone in the entire world. The only one of these villains from Batman’s mythos was the Riddler—the part was played by Frank Gorshin, reprising his role from the 1960s Batman TV show and film. The second part of Legends of the Super Heroes was called “The Roast,” and it featured Ed McMahon as himself, hosting a celebrity roast–style event for the DC heroes who had appeared in “The Challenge,” including Batman and Robin.

Simply put, Legends of the Super Heroes was a torturously bad production. The production’s attempts to create tongue-in-cheek humor by mixing the comic book world with the real world never really had a chance to succeed—that strategy had worked so well for the 1960s screen Batman, but it came across as dreadfully stale by the late 1970s. Being painfully unfunny was not the only problem that Legends of the Super Heroes had—it also suffered from ridiculously cheap-looking sets and woefully bad special effects.

Adam West and Burt Ward must have been mortified once they realized just what a mess they had gotten themselves into by agreeing to appear in the show. Poor Adam West looked as if he had to suffer even more than Burt Ward did. West was fitted with a new cowl for Legends of the Super Heroes that wasn’t long enough in the neck area to allow it to smoothly taper down to his shoulders. Consequently, the loose cowl flopped around his neck the entire program, making it look like he was sporting a double (or triple) chin!

Whether one is a fan of the 1960s Batman screen works or not, one must admit that those works were very well-crafted—their writing, acting, costumes and production values were almost always top-notch. Legends of the Super Heroes was every bit as bad as the 1960s screen Batman was good. Fortunately, Legends of the Super Heroes basically dropped out of sight immediately after it first aired—if too many viewers had gotten the chance to see the special, the general public’s opinion of Batman might well have fallen so low that the entertainment industry would never have risked producing a new Batman screen work!

Eventually, the special did make its way to the home video market—it was released on DVD by Warner Bros. in 2010. One might wonder why Warner Bros. even bothered to release such an awful program on home video. The most likely answer to that question is that Legends of the Super Heroes is one of those productions that is so bad it has become sort of, well, legendary. Trust me, it is so bad that you really have to see it to believe it—so if you are brave enough, it is out there waiting for you!

Fortunately for Batman fans, a much better Batman work with the word “legends” in the title appeared the year after Legends of the Super Heroes first aired. In 1980, DC published the landmark three-part series entitled The Untold Legends of the Batman. The Untold Legends of the Batman marked the first time the character appeared in a stand-alone miniseries, and it retold the origins of all of the major characters in Batman’s world, heroes and villains alike. In the series, Batman is afraid that one of his enemies has discovered his secret identity because someone has been leaving him threatening messages in the Batcave. As he tries to deduce who the culprit might be, he recalls the events that led him to become a crimefighter, as well as some of his most memorable cases. At the end of the series, he discovers that he himself actually left the messages—his bizarre actions are the result of a brain trauma he suffered during a recent case, which has caused him to suffer from temporary schizophrenia. Written by Len Wein and illustrated by Jim Aparo and John Byrne, The Untold Legends of the Batman served as an excellent “summing up” of over 40 years of Batman history, as well as an homage to all of the talented artists and writers who had contributed to that history.

In the early 1980s, Batman was in somewhat of a creative slump. Over a decade had passed since DC’s new generation of writers and artists had revitalized the character, and as wonderful as that revitalization had been, it seemed as if it was time for something new to happen in Batman’s world. In 1983, DC Comics tried to force the issue by introducing a second Robin character. Jason Todd was introduced in issues of Batman and Detective Comics as a young circus aerialist who performed in a trapeze act with his mother and father, Trina and Joseph. Trina and Joseph were helping Batman to find Killer Croc, a criminal with freakish, reptilian-like skin. Croc was becoming a very powerful figure in Gotham’s underworld, and he had vowed to become even more powerful by murdering the Caped Crusader.

Detective Comics #526, May 1983, marked Batman’s five hundredth appearance in the magazine and, to commemorate this auspicious anniversary, the Jason Todd storyline was brought to a dramatic climax. The issue featured a 50-plus page story written by Gerry Conway entitled “All My Enemies Against Me,” which depicted dozens of Batman’s foes, including the Joker, Penguin, Riddler and Two-Face, teaming up to kill Batman before Killer Croc could get to him. In the story, Batman is able to round up and defeat all of his enemies, including Killer Croc, but not before Croc murders Trina and Joseph Todd. At the end of the story, Bruce Wayne decides to make the orphaned Jason his ward, just as he had done with Dick Grayson many years earlier.

“All My Enemies Against Me” set the stage for Jason to adopt the identity of Robin. Of course, Dick Grayson was still fighting crime as Robin, so for the next year or so, the plots of both Batman and Detective Comics moved Jason toward becoming Robin, and Dick toward adopting a new crimefighting identity. Finally, in Batman #368, February 1984, Dick passed on his costume to Jason, formally ending his partnership with Bruce. This decision was reached without any rancor between Bruce and Dick—Bruce wanted Jason to become Batman’s full-time partner, and Dick was ready to establish a life outside of Batman’s shadow. Dick then designed a sleek, capeless costume that was primarily blue in color, and dubbed himself “Nightwing.”

The Robin character’s return to Batman’s world on a basically full-time basis was met with generally negative reviews from Batman fans. Many felt that tradition dictated that Dick Grayson should be the only character to ever don the Robin costume. Plus, the Dick Grayson Robin’s occasional presence in Batman stories kept both “pro–Robin” and “anti–Robin” Batman fans happy—a part-time Robin allowed for appearances of the Batman and Robin team, as well as solo Batman appearances. Fans were also put off by Jason’s origin being such an obvious retread of Dick’s origin. Nevertheless, the Jason Todd Robin remained a fixture of Batman’s comic book world for the next few years.

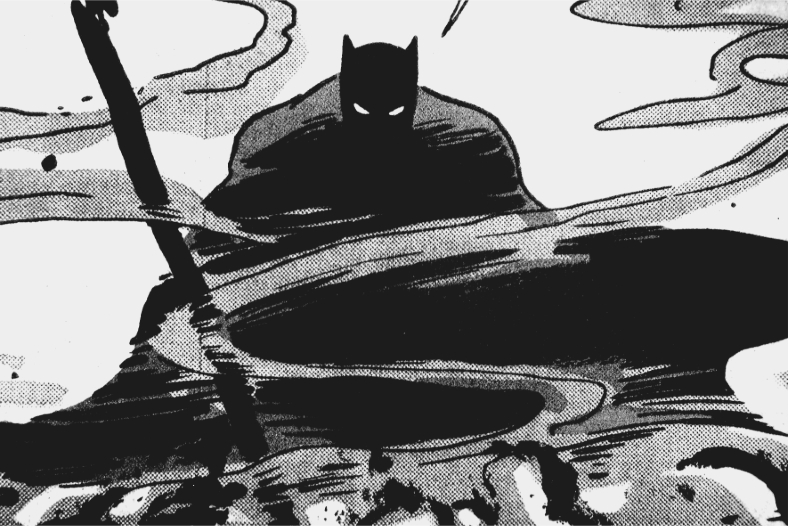

Batman and the Joker in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns #3, “Hunt the Dark Knight” (1986). Art by Frank Miller, Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley.

A form of the comic book commonly referred to as a “graphic novel” was beginning to grow in popularity in the mid–1980s. Graphic novels were basically very high-quality comic books—they featured more pages, heavier paper and better printing than their dime-store counterparts. In 1986, the first-ever Batman graphic novel was published, and it presented a complex, startlingly new version of Batman that completely changed the course of the character’s history. Writer-artist Frank Miller’s four-part Batman: The Dark Knight Returns was set in an indefinite future, and it told the story of what the end of Bruce Wayne’s Batman career might be like.

In Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Wayne is a 55-year-old alcoholic who has given up fighting crime because his second Robin Jason Todd was brutally murdered by the Joker a decade earlier. Gotham City has been overrun by criminals, and Wayne feels powerless to do anything about it. But finally he comes to the realization that he cannot just remain idle while his city crumbles, so he dons his costume for a last series of adventures. One of the first criminals he brings to justice is Harvey Dent, who had supposedly been rehabilitated from his Two-Face persona through plastic surgery and psychiatric counseling.

Batman faces off against a very dangerous and powerful Gotham street gang known as the Mutants, who have vowed to murder his longtime ally Commissioner Gordon. He brings down the leader of the Mutants with the help of an adventurous young girl named Carrie Kelley. Like her predecessors Dick Grayson and Jason Todd, she too adopts the guise of Robin. This new Batman and Robin team is soon faced with an even deadlier enemy, the Joker. The madman snaps out of the catatonic state he has been in for a number of years upon learning that Batman has returned to action. The Joker’s reign of terror finally ends once and for all—Batman gravely wounds the villain when the two fight at a county fair. There the Joker chooses to end his own life, twisting his neck until his spine snaps.

The United States government wants the new Batman and Robin team stopped because they feel they are lawless vigilantes, so they send one of their special agents to put them out of commission. That special agent is none other than Superman, who has just returned from defending the United States from a nuclear attack launched by the Soviet Union. In nuclear winter conditions, Batman and Superman engage in an apocalyptic battle on the very street where Bruce Wayne’s parents were murdered decades earlier.

Superman “wins” the battle because Batman fakes his own death. Carrie is in on the plan, so after Bruce Wayne’s elaborate funeral, she exhumes his body and he goes right back to fighting crime. But not as Batman—he has given up that identity forever, and he will now continue his war on crime as a far more covert operative.

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns was beautifully written and stunningly illustrated, but it was Miller’s richly detailed vision of Batman that really made the series so special; his Batman inhabited a world even more closely tied to reality than the O’Neil-Adams Batman or the Englehart-Rogers-Austin Batman. And the reality Miller created for Batman in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns was an immensely tragic one. The murder of Bruce Wayne’s parents had filled Bruce with a grief that was so crushing, so all-encompassing, that his Batman persona had become more than just a disguise—it had become a kind of psychological escape for Bruce, a wraithlike alter ego that was almost completely separate from his thoughts and actions..

Page after page in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Miller brought readers a Batman that was both haunted and hauntingly real. The physical peril he faced, the calculations he made while striving to prevent crime, the self-doubts he dealt with, all made him seem like an actual, flesh-and-blood person. And the reactions his quest for justice inspired were much the same reactions our world would likely have if there really was a Batman. In Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, politicians and pundits debated the legitimacy of his actions on television news programs, while the general public responded to him with varying degrees of hero worship. Miller’s insights into how our culture perceives heroism, evil and social responsibility were by turns chilling, satirical, inspiring and depressing, but at all times riveting.

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns was a tremendous critical and commercial success, and this success ended up not being confined to the relatively small population of comic book fans. Warner Communications, the parent company of DC Comics, released the series as a one-volume paperback through their publishing company Warner Books. This version of Batman: The Dark Knight Returns sold very well at major bookstores throughout the country, and paved the way for the general public to start taking Batman more seriously than they did when he was viewed as a campy TV show character.

Batman’s re-entry into the general public’s consciousness via Batman: The Dark Knight Returns had a very positive effect on the plans for producing a new Batman motion picture that were commenced by Michael Uslan and Benjamin Melniker back in the late 1970s. Due to a number of corporate takeovers and partnership changes (we’ll discuss those events in more detail next chapter), this Batman film project was now in the hands of Warner Bros.—and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns made Warner realize that a serious screen Batman could be a highly marketable property.

But before Batman would return to the movies, his comic book world underwent a number of radical changes brought on by the phenomenal success of Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. First off, DC Comics completely revamped his relationship with his old ally Superman. Since the mid–1950s, the two heroes had been sharing adventures in World’s Finest Comics and were depicted to be the closest of friends. But Miller’s portrayal of these titans as enemies resulted in DC making relations between Batman and Superman much chillier. DC canceled World’s Finest Comics in January 1986, and from that point on, DC’s two greatest heroes would maintain a relationship that ranged from strained to outright adversarial whenever they appeared together.

This change made for some interesting dramatic tension in stories that featured both Batman and Superman. Even though the heroes basically still worked to achieve the same goal of stopping crime wherever they might find it, their methods were so different that conflict would sometimes arise between them. Batman’s frightening “creature of the night” approach to fighting crime was often at odds with Superman’s straightforward “friendly public servant” approach. This rapport between the crimefighters seemed to be much more true to both of their characters than the three-decades-old tradition depicting them as close confidants.

Another 1980s Batman graphic novel that ended up having a long-range effect on the history of the character was Batman: Son of the Demon, which was written by Mike W. Barr and illustrated by Jerry Bingham. Batman: Son of the Demon was first published in 1987, and told the tale of Batman and his longtime foe Ra’s al Ghul joining forces in order to hunt down a dangerous terrorist known as Qayin. Of course, in Batman’s eyes, Ra’s normally fell under the definition of “dangerous terrorist” as well, but Qayin was such a threat to the world that Batman was willing to work with Ra’s to bring Qayin down.

In Batman: Son of the Demon, Batman and Ra’s’s daughter Talia finally give into their love for one another and become a couple. Talia becomes pregnant with Batman’s child, and at first they are both thrilled at the prospect of starting a family together. But Talia eventually becomes so worried that Batman will unnecessarily risk his own life protecting the child that she lies to him about the pregnancy, saying she has suffered a miscarriage. The story ends with Talia giving birth to the child, a boy, and giving him up for adoption to an unnamed couple. It would take nearly two decades for the implications of Batman: Son of the Demon to greatly affect Batman’s comic history—in 2006, writer Grant Morrison introduced Batman and Talia’s son into the regular continuity of Batman comic stories. We’ll discuss Morrison’s version of the character, a young man named Damian Wayne, later in the book.

The success of Batman: The Dark Knight Returns led DC to contract Frank Miller to create another four-part Batman series. In the series, Miller would retell Batman’s origin in a manner in keeping with the tone he established in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. However, this series would not first be published as a graphic novel, but as stories appearing in regular issues of Batman comics. Batman: Year One, written by Miller and illustrated by David Mazzucchelli, ran in Batman #404, February 1987, through Batman #407, May 1987.

Batman: Year One focuses on Bruce Wayne’s decision to become a costumed crimefighter, and his very first exploits as Batman. As Wayne is returning home to Gotham City after training himself as a fighter, detective and scientist, police officer James Gotham is moving to Gotham to start working for the Gotham City Police Department. Wayne’s very first attempt at fighting crime goes very poorly—he is attacked by several prostitutes, including one named Selina Kyle, and shot by Gotham Police officers. Despite his wounds, he is able to make it home to Wayne Manor—as he sits in his home gravely injured, a huge bat crashes through the window, giving him the inspiration to don the disguise of a bat. Gordon’s first days with the Gotham Police go just as badly—he immediately works to rid the force of corruption, which leads to him being brutally attacked by several corrupt cops.

Batman in Batman: Year One #2, “War Is Declared” (1987). Art by David Mazzucchelli and Richmond Lewis.

Wayne dons his Batman disguise for the first time, and his exploits instantly become the stuff of legend. He even crashes a dinner party being attended by many of Gotham’s crime bosses and crooked politicians to let them know that he plans on bringing them all to justice. This leads corrupt Gotham City Police Commissioner Gillian Loeb to order the Gotham Police to apprehend Batman by any means necessary. A Gotham Police SWAT team eventually corners Batman in an abandoned building, but Batman is able to elude capture by using a sonar device to attract all of the bats in a cave beneath Wayne Manor to him. In the chaos caused by the swarming bats, Batman makes it back to Wayne Manor. Batman’s noble intentions begin to sway Gordon—Gordon begins to see Batman not as a criminal, but as a potential crimefighting ally.

Batman also has a deep effect on Selina Kyle, inspiring her to don a costume and fight crime—disguised as a cat, she attacks a major crime boss named Carmine Falcone. Falcone, hoping to gain back control of his city which has suddenly seemed to go so crazy, unleashes a plan to kidnap Gordon’s son in order to force Gordon to end his fight against Gotham’s corrupt system. Bruce Wayne, sans his Batman costume, is able to foil the kidnapping plot. Gordon is not able to get a look at the man who heroically saved his son, so Batman’s identity still remains unknown to him—but Batman has proven that he is indeed Gordon’s staunch ally. The final panels of Batman: Year One show Gordon on the roof of the Gotham City Police Department, waiting to meet with Batman about a criminal who has threatened to poison Gotham’s water supply. That criminal refers to himself as “The Joker.”

Batman: Year One’s brilliant re-imagining of Batman’s beginnings was hailed as an instant classic. Miller’s compelling storytelling and Mazzucchelli’s spare, no-nonsense artwork had captured Batman in a far more realistic manner than any previous Batman work ever had—indeed, most every panel in Batman: Year One could have been easily acted out in our real world. And Miller and Mazzucchelli’s interpretations of Batman’s supporting characters such as James Gordon and Selina Kyle were every bit as compelling as their interpretation of Batman himself.

Batman: Year One had rendered Batman and his world as an intricate, logical crime drama, and the results were so powerful that the series would prove to be one of the most influential Batman works of all time. (This fact will be made very obvious by the number of times we’ll be discussing it later in this book.) After its initial run in Batman, Batman: Year One was released as a one-volume graphic novel, and enjoyed a commercial success equal to that of Batman: The Dark Knight Returns.

In addition to spawning Batman: Year One, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns also had a significant impact on the future of the Jason Todd Robin character. The graphic novel caused DC to rethink their inclusion of Jason in Batman’s world because it had given voice to most Batman fans’ dislike of Jason. Frank Miller’s decision to have Jason meet his grisly end at the hands of the Joker seemed to be little more than a very thinly veiled expression of Miller’s contempt for the character. This contempt mirrored how poorly Jason was being received by longtime Batman fans. Simply put, DC knew they had a problem in terms of where to go with the Jason Todd Robin, and Miller’s “Jason editorializing” in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns only made the problem that much more obvious.

Premier Batman writer Denny O’Neil had been promoted to editor of DC’s Batman comic titles in 1986. Right after Batman: Year One debuted, O’Neil immediately instigated changes to the Jason Todd Robin character in an effort to make him more popular. In the story “Did Robin Die Tonight?” (Batman #408, June 1987), Jason’s origin, so meticulously set up over the course of dozens of issues of Batman and Detective Comics, was completely nullified.

In the opening of “Did Robin Die Tonight?” Dick Grayson was again Robin, and he and Batman were trying to capture the Joker. In the process, Robin was wounded and almost killed, which led Batman to decide to end Robin’s career. Dick was unhappy about this, but he accepted it—but he also told his mentor that he would continue to fight crime in another guise. (Of course, this allowed Dick to continue appearing in other DC stories as Nightwing, which the character had been doing for the past two years or so.) Just as Batman returned to being a strictly solo crimefighter, he encountered a tough street kid named Jason Todd who was in the process of stealing the tires off of the Batmobile!

In subsequent issues of Batman, Batman eventually took Jason in just as he had Dick (and the first version of Jason!) and make him his partner. This second version of Jason proved to be just as unpopular as the first version. Consequently, O’Neil and company decided to do something very drastic to determine whether or not Jason would continue to be a part of Batman’s world. DC held a phone-in poll for Batman fans to determine whether Jason would die at the hands of the Joker, in effect making Jason’s fate as depicted in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns the character’s “official” fate, or whether he would survive the Joker’s attack. The poll was held in mid–September 1988 and, not surprisingly, the fans voted to kill off Jason. So in a series entitled “A Death in the Family” (Batman #426, December 1988 through Batman #429, January 1989), Jason was severely beaten by the Joker, and then killed in an explosion that the madman had set.

DC’s decision to allow the Jason character to be killed off sparked quite a bit of media coverage. All of the major news media outlets knew a potentially compelling headline when they saw one, and “ROBIN THE BOY WONDER DEAD” certainly was a headline that would grab the public’s attention. Of course, many people did not pay enough attention to the details of the story to realize that it was not the “classic” Dick Grayson Robin that DC had eliminated, but his very unpopular successor.

Most comic book fans had followed the genre long enough to know that even though Jason was gone, a new Robin was bound to be introduced before too long. After all, Robin remained one of the most recognizable comic book characters of all time—he was far too valuable a property to simply abandon. These comic book fans were right, of course: Plans were underway to introduce yet another Robin into Batman’s comic book world even before the ink was dry on issues of “A Death in the Family.” (We’ll discuss this third Robin later in the book.) So DC’s decision to portray “the death of Robin” as a major, irrevocable milestone in the history of the Batman character really amounted to nothing more than a crass publicity stunt.

The demise of another Batman icon was handled with considerably more thought and finesse in a graphic novel entitled Batman: The Killing Joke, released in late 1988. Written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Brian Bolland, it told the chilling tale of the Joker gunning down Barbara Gordon as part of an elaborate plan to drive Commissioner Gordon insane.

In Batman: The Killing Joke, the Joker thinks back on his life and contends that the only reason he became an insane, murderous criminal was because of monstrously bad luck. The Joker remembers himself as an unsuccessful comedian who agreed to help some criminals pull off a robbery at a chemical plant where he had previously worked. Unknown to the comedian, the criminals had come up with a clever master plan to make their role in the robbery look insignificant—they made the comedian wear a red hood and cape, so it seemed that he was the costumed mastermind of the robbery.

Batman and the Joker in Batman: The Killing Joke (1988). Art by Brian Bolland.

The comedian’s sole reason for taking part in the robbery was to obtain money for himself and his pregnant wife. But right before the robbery was to take place, his wife and unborn baby were killed in a freak accident. In spite of this tragedy, the criminals still forced him to don the guise of “the Red Hood” and help them. Batman broke up the robbery attempt and the comedian fell into a vat of acid, turning his skin white and his hair green.

As far as the Joker is concerned, the loss of his wife and his fall into the acid drove him insane—in fact, the Joker feels that anyone would be driven insane if they had to face the kind of horrific events he faced. In order to prove this theory, he shoots Barbara Gordon and photographs her terribly wounded body. The Joker then kidnaps Commissioner Gordon, holds him prisoner at a run-down amusement park, and forces him to look at these awful pictures of his beloved daughter over and over again—the criminal will drive the Commissioner mad just to prove that his actions are not his fault, it is the random cruelty of life that is responsible for his insanity.

Batman eventually tracks the Joker down and saves the Commissioner—in spite of all the Joker’s efforts, Gordon has retained his sanity. And Barbara has survived the Joker’s attack—but she will be confined to a wheelchair for the rest of her life. While in the process of apprehending the Joker, Batman tells the criminal that Gordon is still sane. Batman goes on to tell the Joker that Gordon has proved the criminal wrong, people can strive to overcome tragedy and lead meaningful lives. Batman: The Killing Joke ends with Batman trying to convince the Joker to try to rehabilitate himself—maybe Batman can even help him find his way out of the maze of insanity and violence that his life has become. The Joker tells Batman that it is far too late for that; consequently, the war between them will simply go on and on.

Batman: The Killing Joke’s combination of Moore’s emotionally deep storytelling and Bolland’s realistic, beautifully detailed art made the graphic novel among the greatest Batman comic works of all time. And the book included an ingenious nod to the history of the Joker character—its exploration of the villain’s origin as “the Red Hood” was inspired by the classic comic book story “The Man Behind the Red Hood!” which was first published in Detective Comics #168, 1952. (We discussed that story in detail in Chapter 5.)

But the most ingenious aspect of the book was that even though it gave the Joker a far more detailed backstory than he had ever received before, it was made clear that this backstory was only a possible origin of the criminal, not the “definitive” one. The Joker says during the course of the book that he thinks he remembers what happened to him in terms of his wife dying and his fall into the acid, but because he is so mentally unstable, his memories of these events tend to vary wildly. Consequently, Batman: The Killing Joke did not tie the character down to any specific pre–Joker identity, allowing the roots of his psychotic behavior to remain largely a mystery.

Batman: The Killing Joke’s most long-ranging contribution to Batman mythos was that the Joker’s horrific actions ended the crimefighting career of Batgirl. Batgirl’s demise had far more impact on Batman fans than the death of Jason Todd in “A Death in the Family.” As previously mentioned, killing off the unpopular Jason on the basis of a phone-in poll seemed like nothing more than a cheap publicity stunt, so it carried little emotional resonance for Batman fans. But the Barbara Gordon Batgirl had been a character that had remained popular with many Batman fans over the years, so seeing her taken out of action so completely was somewhat of a shock to them.

Barbara’s injury turned out to be a plotline that lasted for decades. In the world of comic books, characters are often gravely injured or killed, but writers will often concoct some way to bring that character back to full strength after just a short time. This was not the case with Barbara—she remained paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair. She became a computer expert and, after dubbing herself “Oracle,” began assisting Batman and other heroes in the gathering of information pertaining to cases they were working on. Barbara’s transformation from Batgirl to Oracle seemed to emphasize Batman: The Killing Joke’s hopeful concept that people have the power to overcome adversity and find purpose in their lives, if they are only willing to look deep inside of themselves to find that power.

Incidentally, DC did eventually decide to rewrite Barbara’s history so that she could return to action as Batgirl after the events of Batman: The Killing Joke—but that rewrite did not debut until late 2011, 23 years after Batman: The Killing Joke was first published. We’ll discuss Barbara’s second round of Batgirl adventures much later in the book.

Interestingly, Frank Miller’s Batman works and the Moore-Bolland Batman: The Killing Joke ended up being widely regarded as the best Batman graphic novels of the 1980s, even though Miller’s and Moore’s interpretations of the character were so radically different from one another. Miller saw Batman as a soul so tortured that he was almost as unbalanced as the criminals he fought. Moore’s Batman was undoubtedly very grim and driven, but he was most definitely not mentally unstable. In fact, the whole point of Batman: The Killing Joke was that heroes like Batman and the Gordons were able to find a way to hold themselves together in the wake of enormous personal tragedy. This characteristic was one of the main things that separated them from villains like the Joker.

Obviously, Moore’s version of Batman was far closer in spirit to the way Batman had usually been portrayed since his 1939 debut. But while Miller’s version of the character did not have the strength of tradition behind it, many Batman fans found it to be a compelling new way of interpreting their hero. At any rate, by the late 1980s there were many Batman fans who felt that the character should be portrayed as being mentally stable, and just about as many who felt that he should be portrayed as mentally unstable. Batman’s adventures were about to begin proliferating at such an incredible rate that before long, there would be enough different kinds of Batman stories being published to keep both of these camps relatively happy.

Nineteen eighty-nine was the year that was going to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Batman character’s debut in Detective Comics #27, and DC Comics was preparing to celebrate the occasion very proudly and publicly just as they had when Superman turned 50 the year before. Of course, Batman’s anniversary ended up being commemorated in a manner far larger than any celebration DC could have ever assembled. In June 1989, the long-awaited Warner Bros. motion picture Batman starring Michael Keaton as Batman and Jack Nicholson as the Joker was released, and it became one of the most commercially successful films of its time. We’ll discuss that film in detail next chapter.