Tommy Caldwell going for a 40-footer on Broken Brain (5.12), Indian Creek, Utah

Tommy Caldwell going for a 40-footer on Broken Brain (5.12), Indian Creek, Utah

Climbing is bound by the laws of physics. Physics determines how a climbing move should be made, whether or not your foot will stick on a hold, and why a cam holds a fall. Physics also determines how much force is generated in a climbing fall. The thing about climbing physics is that although it deals with relatively simple concepts (like gravity), the real-world physics of climbing gear and climbing gymnastics is extremely complex.

This chapter discusses

![]() Newton’s laws of motion and how they relate to a falling climber,

Newton’s laws of motion and how they relate to a falling climber,

![]() how gravitational potential energy becomes kinetic energy—the energy of motion—in a fall,

how gravitational potential energy becomes kinetic energy—the energy of motion—in a fall,

![]() how the belay method can drastically affect the impact force in a leader fall,

how the belay method can drastically affect the impact force in a leader fall,

![]() what the fall factor is and how it influences impact force,

what the fall factor is and how it influences impact force,

![]() how the UIAA tests ropes to measure their impact force.

how the UIAA tests ropes to measure their impact force.

For some climbers, enduring this chapter might be more painful than grinding up a feldspar-lined off-width. If you find your eyes rolling up into your head, your eyelids drooping, or your brain screaming for diversion, don’t worry. Just start with the sidebar on relevant lessons, drop the book, load your pack, and go climbing—but while you’re at it, study the physics of gear placements, direction of pull, fall trajectories, and climber/belayer weight differences. If you’re a true glutton, a student of physics, or just really bored, read on for a deeper understanding of climbing physics.

NEWTON’S LAWS OF MOTION

Issac Newton pondered a falling apple. He may as well have considered a falling climber while devising his laws of motion, which define the motion of bodies.

The rate of acceleration of an object is proportional to the force applied to the object. Gravity definitely seems to tug harder some days than others, but it actually pulls us toward the earth’s center with a constant force that is equal to our body weight. In a free fall, gravity accelerates a falling climber’s body at 9.8 meters per second2 (32.2 feet per second2). Thus, a climber in free fall will fall 4.9 meters the first second, and because the falling climber is accelerating and not continuing at the same speed, they will fall three times farther the next second, and five times farther the third second. The body accelerates for about five seconds until it reaches approximately 122 miles (196 kilometers) per hour—terminal velocity: the speed where wind drag balances gravitational pull.

A falling climber accelerates at 9.8 meters per second2 until the rope arrests the fall. If the rope were a cable, the climber would halt almost instantly; the rapid deceleration would create a massive impact force on the climber and the protection, damaging the climber’s internal organs and blowing out the climbing anchors. Dynamic climbing ropes stretch to control the climber’s rate of deceleration, thereby limiting the impact force on the climber and the gear.

Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. When we stand, the ground pushes up with a force equal and opposite to our body weight. While climbing, the hand- and footholds support a force equal to our weight (when we use the holds to oppose each other, they support more than body weight). In a fall, the rope creates a force to catch us; this is called the impact force. The impact force on the rope pulls on the belayer, who must oppose the rope’s pull. The top anchor holds a force equal to that of the climber and the belayer combined (if we ignore rope drag), and the rock surrounding the top anchor opposes the forces created by the anchor—hopefully—or else the anchor fails. The forces created in a lead fall begin with the falling climber, then transfer through the rope to the belayer, anchors, and ultimately the rock to fulfill the equal-and-opposite reaction of Newton’s third law.

POTENTIAL AND KINETIC ENERGY

When climbing, you work to move your body mass upward against gravity. Some of the energy used to climb becomes gravitational potential energy—energy stored due to the pull of gravity and your position above the earth. If you take a leader fall, potential energy quickly converts to kinetic energy—the energy of motion—as gravity accelerates your body downward. The farther you fall, the faster you go, as your body’s potential energy becomes kinetic energy.

As you climb, you store more potential energy. If you fall, the potential energy becomes kinetic energy, the energy of motion.

Herein lies the double whammy of “running it out”: a longer fall increases the chance of hitting something and increases the speed at which you hit it. The more speed you have, the more energy available to smash your bones if you hit a ledge.

Setting protection decreases the length and speed of a potential fall. The obvious conclusion: more protection means more safety . . . to a point. More protection also means more time spent fiddling with gear, more physical and mental energy devoured, and more gear carried. Every leader should seek a balance between safety and efficiency.

In a clean fall on a vertical or overhanging face with no ledges to hit, the rope absorbs most of the energy by stretching. Some energy also goes into overcoming rope friction from the carabiners and the rock, and perhaps lifting the belayer. If the impact force is high, some energy might go into forcing the rope to slip through the belay device and belayer’s hand, provided that she’s belaying with a device that does not lock the rope. If the fall isn’t clean and the climber hits a ledge, much of the energy can go into breaking his bones.

When top-roping, a fall is halted almost immediately. A short fall creates less chance of hitting something, and it also limits the amount of potential energy transformed into kinetic energy, so the speed of the fall is slow. This is what makes top-roping so safe.

IMPACT FORCE

In a lead fall, the climber’s body exerts an impact force on the rope that must be countered by the belayer. Friction at the high carabiner and from the rope running over the rock and through other protection allows the belayer to feel less impact force than the leader. The force on the top protection equals the force on the climber and the belayer combined. The magnitude of the impact force created is largely determined by

![]() the belay method,

the belay method,

![]() the fall factor,

the fall factor,

![]() body weight,

body weight,

![]() rope elongation.

rope elongation.

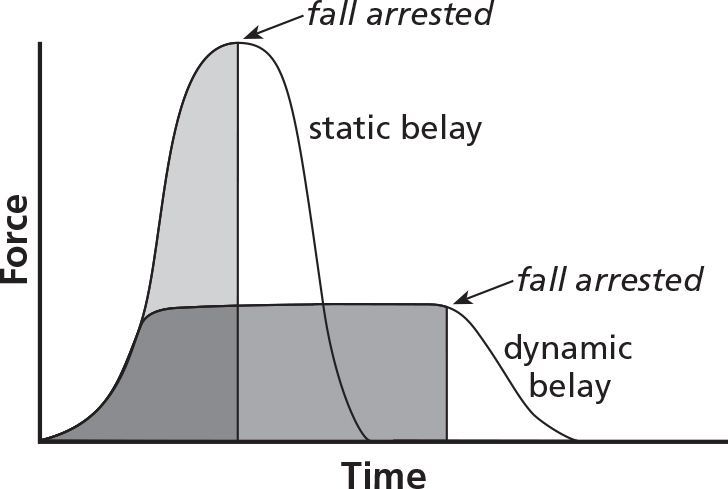

BELAY METHOD

A dynamic belay, where some rope slips through the tube- or plate-belay device as the fall is stopped, arrests a fall more gradually. This can dramatically decrease the impact force in a fall with a high fall factor (see next section). The dynamic belay is usually unintentional—a belayer’s hand can hold only so much force, so some rope automatically slips in a hard fall. A good belayer might also intentionally let some rope slip through the device if the climb is overhanging so that the climber does not smack the wall as hard.

If the belayer uses an assisted-braking device, the rope locks tight in a fall. If the belayer is also tightly anchored, the belay will be almost totally static and will create the highest impact force possible for that fall. Assisted-braking belay devices should be used only when the protection is bomber, such as on well-bolted sport climbs or trad routes with perfect crack protection. Even on such routes, climbers should be aware that the impact force can be massive if the leader falls while close to the belay. On overhanging climbs, a static belay can cause the leader to swing hard into the wall, a mistake that has caused numerous broken ankles.

Using an assisted-braking belay device in conjunction with an upward-pull anchor as shown here creates a very static belay, particularly when there is not much rope between the belayer and the leader. This could cause marginal pieces to fail or cause the leader to swing violently into the wall.

If the belayer is on flat ground and using an assisted-braking device, she can jump up as the force of the fall comes onto her. This is similar to having some rope slip through the belay device; it adds some dynamics to the belay and decreases the impact force. These differences are significant. A larger belayer will need to intentionally move upward with the force of a fall in order to prevent a hard fall by a smaller climber. Larger belayers can provide soft catches with an assisted-braking device by standing a short distance away from the wall and stepping or jumping upward as the force of the fall hits the end of the rope. An easier and more reliable way for a larger belayer to give a softer (more dynamic) catch is to use a regular tube or plate device.

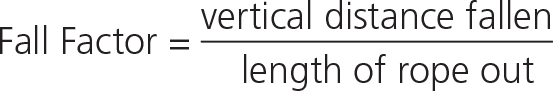

FALL FACTOR

The higher the fall factor, the greater the impact force in a fall. The important concept of the fall factor is that falls close to the belay create the highest forces because only a little rope exists between the belayer and the climber to absorb the energy of the fall. As the leader gets higher up the pitch, more rope comes into the system to stretch and absorb energy, so the force created in a fall decreases (provided that the leader has regularly placed protection).

The fall factor takes into account the amount of energy released in a fall and the length of rope available to absorb it. Two falls with equal fall factors theoretically create the same impact force regardless of the distance fallen (if the rope, climber weight, and belay method remain the same). Obviously, a longer fall might be more dangerous because of the increased chance of hitting something, but the forces generated are similar because the long fall has more rope available to absorb energy. The longer fall is also more severe because the force impacts the climber and anchors for a longer time.

A true factor-2 fall can occur only when the leader is directly above the belay on a vertical wall with no protection, so the fall is twice the length of the rope out. A factor-2 fall creates the greatest force possible on the climber and belayer if the belayer is using a device that allows minimal rope slippage. If the belayer is using a tube or plate device, rope will slip through the device, which significantly decreases the forces but could burn the brake hand of the belayer. The force of such a fall comes directly onto the belayer and the belay anchors, making it a hard catch and creating an exceptionally high load on the belay anchors. Recent studies have shown that true factor-2 falls cause enough force to injure the belayer—it is best to climb in such a way that you never take a factor-2 fall. Safe climbers avoid factor-2 falls by setting solid protection just above the belay and by climbing with a free soloist’s control if a runout off the belay is necessary. The first few pieces of protection in a pitch are critical because they decrease the fall factor and back up the belay anchors.

As you climb up a pitch, more rope feeds into the system. More rope means more capacity to absorb energy. A 10-foot fall from 100 feet above the belay creates substantially less force than a 10-foot fall near the belay, because the rope stretches more in the longer fall.

The fall factor is the distance that you fall divided by the amount of rope out. In this case, a 30-foot fall on 45 feet of rope makes a fall factor of 0.67.

BODY WEIGHT

On any given day, your body weight is a fixed amount; gear and clothing add to your effective weight. Larger climbers create higher impact forces when they fall, so they might consider climbing on thicker ropes and placing extra protection or setting beefier belay anchors in some situations.

ROPE ELONGATION

A dynamic lead rope is really just a long spring. When a rope catches a fall, most of the kinetic energy goes into stretching the rope and is ultimately dissipated as heat that is caused by friction between the rope fibers; some of the energy even transforms into molecular changes in the rope fibers.

As you climb higher up a pitch, the length of rope between the climber and the belayer increases. More rope out means more capacity for the rope to stretch and absorb energy, which results in a lower impact force and a longer fall. Some ropes stretch more than others to give a soft catch; these low-impact-force ropes decrease the force on the protection, climber, and belayer, but the extra stretch might increase your chances of hitting a ledge.

As a dynamic climbing rope catches a fall, the force on the climber, belayer, and anchors builds as the rope stretches. At the instant when the rope reaches its maximum stretch, the load reaches its maximum impact force. Then the force diminishes until the top anchor holds only the climber’s weight and some of the belayer’s weight.

MOMENTUM AND IMPULSE

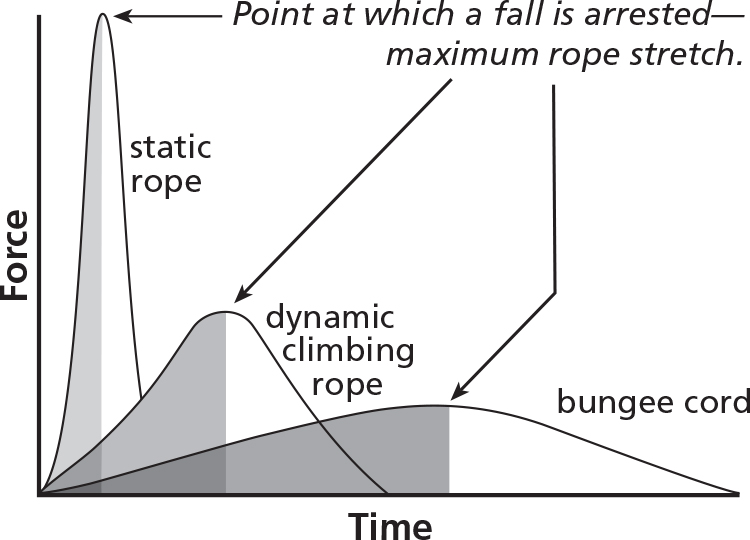

The momentum of an object equals its mass times its velocity. The faster an object is moving or the heavier it is, the more momentum it has. If you graph the impact force as it grows from zero to the peak force, the area under the curve equals the impulse, which is the change of a falling climber’s momentum. You can calculate the impulse by multiplying the climber’s mass by his change in velocity.

A falling climber slows from maximum velocity the instant the rope begins arresting the fall to zero velocity once the fall stops, which occurs at the instant of peak force. The change in velocity, therefore, equals the maximum velocity reached in the fall, because the final velocity is zero. In a clean fall, the length of the fall determines the maximum velocity.

The static rope doesn’t stretch much in a leader fall, so the duration of the impulse is short, causing the impact force to spike. A dynamic climbing rope stretches enough to keep the forces reasonable without dropping the climber too far. A bungee cord, on the other hand, stretches so much that the time to arrest the fall is relatively long. This keeps the impact force low but increases the length of the fall so much that the climber is likely to get battered on the way down.

Halting a fall creates a given impulse—equal to the climber’s mass times the maximum falling velocity. As mentioned above, this is the area under the force-versus-time curve. A static rope stretches little, so it stops a leader fall quickly. The rapid arrest drives

A dynamic belay increases the time to arrest the fall, thereby decreasing the impact force. A static belay halts the fall rapidly, creating a much higher peak force. The impulse is the same for either belay method, so the area under the force-versus-time curves is equal.

Lilla Molnar pondering fall potential during a first ascent in the Purcell Mountains, Canada

A dynamic climbing rope is a compromise between the static cord and the bungee. It stretches just enough to keep impact forces in worst-case falls within a range that the human body can tolerate. A dynamic rope creates the same impulse to stop a falling climber as a static rope or a bungee, but it creates much less force than a static rope and stretches far less than a bungee.

STRENGTH OF CLIMBING GEAR

Climbing gear is designed to be functional, light, and able to withstand climbing falls. The list below shows the range of strengths for various pieces of gear from different manufacturers.

CLIMBING GEAR STRENGTH RANGE |

||

|

kilonewtons |

pounds |

Nuts and Cams |

||

Micronuts |

2–7 |

450–1,575 |

Small wired nuts |

4–7 |

900–1,575 |

Medium wired nuts |

6–12 |

1,350–2,700 |

Large wired nuts |

10–12 |

2,250–2,700 |

Small cams |

3–10 |

675–2,250 |

Cams |

12–14 |

2,700–3,150 |

Rope |

18–22 |

4,000–5,000 |

Carabiners |

||

Full strength |

23–25 |

5,175–5,625 |

Gate-open strength |

7–10 |

1,575–2,250 |

Cross-loaded strength |

7–10 |

1,575–2,250 |

Locking carabiners |

23–30 |

5,175–6,750 |

High-Strength Cord |

||

5.5–6 millimeter |

14–21 |

3,150–4,800 |

Nylon Cord |

||

5 millimeter |

5–5.7 |

1,134–1,280 |

6 millimeter |

7.4–8.7 |

1,653–1,955 |

7 millimeter |

10–14 |

2,250–3,210 |

Webbing Slings |

||

8–12 millimeter Spectra/Dyneema |

22 |

4,950 |

18 millimeter nylon |

22 |

4,950 |