19

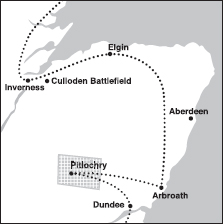

Pitlochry

My base for the next few days before rejoining Boswell and Johnson was the tourist town of Pitlochry with the attractive River Tummel winding through it. The town, however, isn’t especially attractive. It is filled with stores catering to visitors, and unless you drive well off the main road into the residential area, you would have no idea that Pitlochry has any permanent population.

The town advertises itself as the “Gateway to the Highlands” and even if it isn’t quite that it was good enough for my needs. I stayed just off the very busy main road in a large, rambling guest house built in 1881 and hosted by an easy-going, quick-to-laugh Irishman named Jim. Jim’s breakfasts were delightful: fresh juice (I kept looking for the orange trees in the backyard), tasty sausage, well-cooked eggs, and opera. The last was a pleasant surprise: a background of Mozart, Bellini, Rossini, and Verdi, most of which I could identify, to Jim’s surprise. “You Yanks think you know a bit of opera, eh?” he said with a challenge one morning. Moments later Jim walked out of his kitchen, chef’s hat in place, singing at full voice an unfamiliar Irish song. I conceded.

Before succumbing to yet another castle, I drove three miles into the Grampian Mountains to the Pass of Killiecrankie, another memorable battle site. It is spectacularly situated in a steep, heavily wooded gorge through which runs the fast-moving River Garry. The explorer Thomas Pennant described it as “a scene of horrible grandeur.” It’s part of a natural corridor linking the Scottish Highlands and the Lowlands, therefore a likely place for a battle. The one here took place on July 27, 1689, and if you guessed that it somehow involved the Jacobites you would be correct.

In fact the first of the Jacobite rebellions occurred at this time, shortly after the Stuart King James VI (of Scotland) and II (of England) was chased off the throne and fled to France. The rebellious clans were led by John Graham of Claverhouse, viscount Dundee, while the government opposition—mostly Lowland Scots—was led by another Scot, the Highlander General Hugh Mackay. His army was making its way through the narrow pass headed to Jacobite-held Blair Castle when Dundee’s soldiers attacked; they charged forward into Mackay’s line. Swords swung, heads rolled, and the blood flowed. Within a matter of minutes the outcome was decided: Mackay’s men could not advance and were pinned down, and they fled in a rout. Mackay joined them, leaving behind nearly two thousand men dead, wounded, or captured—nearly half of his army. Dundee was mortally wounded, however, and the attempts by others to follow up the victory failed, as, ultimately, did the Jacobite cause.

There is an amazing story about one moment in the battle that has become a part of the lore of Killiecrankie. It has to do with one of the government’s soldiers, one Donald MacBean. During his retreat MacBean found himself on a rocky ledge with his enemy in hot pursuit and seemingly only one avenue of escape: jumping hundreds of feet below into the River Garry. Instead MacBean made a prodigious and still-hard-to-believe eighteen-foot leap across the gorge to the rocks on the other side. MacBean left a colorful memoir in 1728 that detailed his narrow escape. Visitors to Killiecrankie can see the site of this dramatic incident as they walk over the area.

So much for battles, though; it was time for more castles. First up: Glamis, a castle associated with royalty since 1034 when King Malcolm II was wounded and brought here to die. Not a good omen, perhaps, but things worked out fine for the king. Work on the castle as it survives today—and it is quite handsome inside—was begun in 1400; it has prospered over the years because of its royal associations. Queen Elizabeth’s mother, the Queen Mum, was born here, and so was Princess Margaret.

Not too far away is Menzies Castle, built in the sixteenth century and occupied until 1918. Its condition had declined precipitously until Clan Menzies acquired the dilapidated structure in 1972 and began a restoration, which is still under way. The restorers have done a splendid job, leaving the interior mostly empty and using occasional pieces of period furniture to suggest how the rooms might have looked. One of them is known as “Prince Charlie’s Room” because the Young Pretender slept there in February 1746 when he was retreating with his army toward Inverness. There is also a death mask of Charlie on the wall, not at all grisly. The castle seemed truly medieval, and the tour was very instructive and appealing.

Finally, because I was so close to the town of Kirriemuir I couldn’t resist seeing the home of another well-known Scottish writer: J. M. Barrie, the creator of Peter Pan. It took a bit of wandering around the small town before I located the unpretentious two-story cottage where he was born in 1860. Barrie recounted in a memoir written in 1896 that “On the day I was born we bought six hair-bottomed chairs, and in our little house it was an event.” Presumably so was his birth, although Barrie was one of ten children, so perhaps it really wasn’t as big a deal as getting the chairs after all. Two of those chairs survive and are still in the house. Outside was a small wash house with a communal pump where the young Barrie and his friends acted out his first play, written when he was seven. There was also an exhibit showcasing costumes and the program from the first production of Peter Pan in London in 1904. Barrie left Kirriemuir at the age of eight to attend Glasgow Academy; he died in 1937 at the age of seventy-seven.

I knew I had put things off long enough. Leaving Kirriemuir and the celebration of Barrie’s achievements, I headed to Blair Castle in spite of the “horrible grandeur” that I knew awaited me there. Blair Castle at Blair Atholl, some five miles from Pitlochry, was the scene, I hated to recall, of my great embarrassment years ago during my first visit to Scotland. It was there that I met the gracious Iain, tenth duke of Atholl, and greeted him with—my teeth are starting to itch as I write this—“Good morning, Duke.” I’ve already described the scene, but arriving on the spot I could not delete the memories. I wondered as I approached Blair if the duke would still be there, a much older man to be sure, but still able to recognize the bald American who offered such a laughable insult many years before. I hoped to see him again and apologize.

Blair is a fascinating, eye-catching castle. It has the requisite turrets and high walls, but it also has lovely landscaped grounds with herds of cattle grazing peacefully and strutting peacocks picking their way through the car park. Bagpipers usually play at the front of the castle as visitors arrive; they are members of the Atholl Highlanders, a select group of men retained by the duke as his private army. It’s the only private army in Scotland, and the privilege was granted to the Atholls by Queen Victoria in 1844.

The castle goes back to 1269 and has seen its share of winners and losers, Jacobites and royalists, adventurers and politicians. The family was badly split during the Jacobite Rising when the duke and his second son supported the government and the eldest and youngest sons were Jacobite enthusiasts. And yes, Bonnie Prince Charlie stayed here for a while on his march southward to capture Edinburgh. The effects of war and the economic depression forced the family to open the castle to the public for the first time in 1936; it has since become one of Scotland’s most visited castles, thanks in large part to the efforts of the tenth duke, my friend Iain.

I took the tour of some thirty rooms, and they were as magnificent as I remembered from years before. But I saw no sign of the duke’s presence. Back outside later I stood listening to the bagpiper, and when he took a break, I invited myself into conversation. I first told him an abbreviated version of my embarrassing story on meeting the duke, and he smiled. “He was indeed a very fine man, the duke was,” he said, “but he died in 1996, I’m afraid.” I knew the duke would have had to have been old, but I was surprised and deeply saddened when I heard that. “He passed away quietly. I miss him. I think we all do. A lot has changed here since his passing, and not for the better. The castle is now in the hands of a family charitable trust. It’s not the same, my friend. I’m glad you met him when you did. You met a great man.”

I discovered later that the tenth duke, who was childless, had placed the castle, its contents, and the surrounding estate into a trust in 1995, the year before his death. His action ensured that Blair would remain open to the public and be cared for by a private corporation. That was good. But I couldn’t get over my regret that I never had the opportunity to apologize to the duke for my faux pas. I was sure he had forgotten it; he had far more important matters to deal with. But I really would have given a lot for the opportunity to thank him for his kindness. I drove back to my lodging in Pitlochry and drank a toast in his honor. I told Jim my little story the next morning. He was sympathetic: “If you’d called me, I’d have shared that drink with you,” he said. I wish I had.