How to Develop Appropriate Friendships That Benefit the Team

“I wouldn’t be able to survive the crazy if I didn’t have Jennifer there,” said Amalia, a physical therapist who works on a team with six others, including her best friend. “And believe me, there is so much crazy.” I’ll spare you the stories that ensued—mostly about their boss acting unethically, but also plenty of stories about their cranky and demanding patients—but it ended with her reiterating again how much her friendship made the job tolerable.

They have built a solid friendship: they both joined a roller derby team last year that practices together weekly, they frequently attend baseball games together with their husbands during the season, and they’ve done a couple trips to Las Vegas together. But it’s not how they moved their friendship to Frientimacy that impresses me as much as what they’ve done in the workplace that bears telling.

She and Jennifer made a pact to try to raise the morale of the other therapists, hoping to help offset what otherwise felt like a toxic environment. From decorating an unused bulletin board with “Getting to Know Your Therapist” photos and fun facts for the patients to see to coordinating holiday potlucks with everyone on the team—they recycled the energy their friendship gave them and shared it with the others.

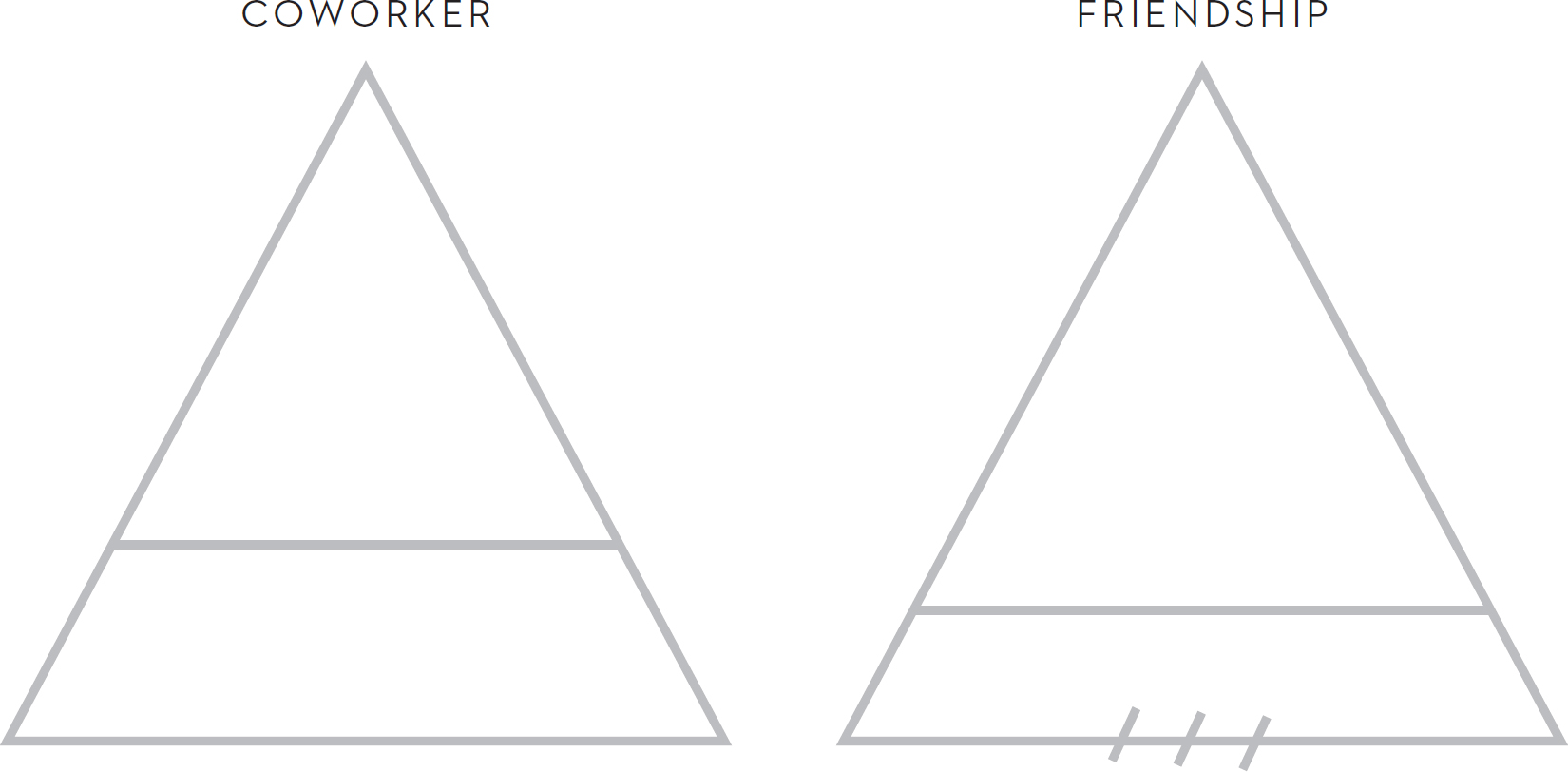

It’s all too easy to find our “Jennifer” and cling to the friendship that is developing, but if we want to move a friendship up the Triangle, we’d be wise to practice how we can best protect it from the pressures of work and use it to raise the sense of connection in our entire workplace.

Be Generous with Intentional Positivity to Everyone Else.

Our first call to order, as illustrated so beautifully by Amalia’s story, is to extend the Positivity we feel with each other to those around us.

Be the joy. The responsibility of those of us who are enjoying our friends at work is to recycle that joy to the rest of the team. Our friendship should be a gift to everyone around us—they should want to be around us. Because we are comfortable with one another and enjoy one another, we can help set a tone of gratitude, humor, and fun at our team meetings, parties, and desks. Our closeness should be felt as something that envelops others in it with us when we’re at work, not something that feels exclusive.

Express affirmation. To offset the insecurities that others might project on our friendship, we must make sure that no one doubts that we see and appreciate everyone else. It’s crucial for both people in the friendship to step up their game and be known as people who cheer-lead and voice appreciation. To that end, we’ll do all we can to never give anyone reason to worry that we are competing with them, trying to elbow our way in, speaking poorly of them, or sabotaging them. On the contrary, we hope that they feel nothing but love from us. (Especially true if we’re friends with the manager. The manager’s success is based on the success of the team—so be someone the manager can trust to intentionally help build up the members of the team.)

Increase the Vulnerability to Talk about Our Relationship

Second, both of us are going to step up our Vulnerability—in this case by being willing to honestly have conversations that can help safeguard our relationship from various possible threats.

Proactively talk about our relationship. If we’re mature enough to build these friendships, then we’re mature enough to talk about them.

Toward the end of a conversation one day about what they didn’t like at work, Jennifer asked Amalia, “What can we do to help make sure we don’t get sucked into the vortex of pessimism?” It validated there was an “us” and elicited a conversation that set them on the path to fostering fun around them.

And it’s always easier to do so before there’s a reason to do so. In other words, don’t wait until issues come up. Try to think through as many of them ahead of time as possible. We can easily say to each other, “Hey, I’ve been loving our friendship and to help protect it from all the stuff that can come up in a shared workplace, would you be willing to meet for drinks one night when we can talk through what would feel best to each of us?”

Some possible questions:

• How do you think others feel about our friendship? Is there anything we could do differently to help them feel better/less worried?

• What would be the worst-case scenario you could imagine? What, if anything, could we do to help prevent some of those things from ever happening? How would you want me to respond in that situation if, God forbid, we ever find ourselves in that worst-case scenario?

• What will be the hardest part of this working relationship for you?

• If one of us ever feels like we have to tell the other one something that might hurt our feelings—how would you want me to do that?

• What kind of scenarios tend to stress you out the most? And what signals do you give off that would help me see what you’re feeling?

• What boundaries do we want to put in place to help safeguard our working relationship and our friendship?

• If you could ask anything of me, what would it be?

• I know you well, but if you were to come with a warning label—what would it be? What could you share with me that would help me better protect us?

• What do you most need from me while we’re at work?

• What are some of the most supportive things I can do for you at work? What feels helpful?

Basically, we want to have as many conversations ahead of time so that we both feel more confident that we can rely on the relationship in meaningful ways and feel better equipped for having to handle situations as they arise. These conversations help set healthy expectations, reminding us that just because we’re friends doesn’t mean we won’t have some challenges ahead.

Keep clarity and confidentiality in each role. This one doesn’t need a ton of explaining, but we don’t break our confidences, or boundaries—either at work or in the friendship.

Most successful friendships at work include boundaries about how we treat each other differently at work than we do outside of work. One supervisor shared with me that they call it out by pretending to take a hat off when they say, “Okay, now I’m taking my friend hat off and am saying this as a boss.” Another clarified, “Some days my friend barely even says more than hello to me at work, and I’m completely okay with that as we’re both clear that we care for each other, but we have different roles in this building.” And as one cadet in the Marine Corps said to me, “What happens in the barracks at night has no bearing on whether I salute my superiors the next morning.” We don’t forget our separate roles . . . nor take it personally when we sometimes have to act differently in each setting.

Furthermore, we don’t tell our friend details or private information about projects or people at work that isn’t theirs to know. Obviously, the longer we’ve known each other, the more we’re mutually sharing and the safer we feel in the friendship. It’s unrealistic to think we won’t be processing decisions and ideas with each other that may put us into some gray territory, but that’s all the more reason to be clear ahead of time what details aren’t appropriate or when we need to be vague.

And, on the flip side, we don’t bring personal stuff we know about each other to work. For example, if we were at our friend’s house over the weekend, that probably doesn’t need to be mentioned during the Monday morning group share. We don’t need to hide that we’re friends, but we definitely don’t need to keep it in everyone’s face.

Lastly, look for ways to assure others that we aren’t talking about them. When a colleague references something they assume we know because our friend told us, we’ll be quick to say, “Oh, actually I didn’t know that. We’re very careful to not talk about anyone on the team.” A few blatant lines like that over time helps build the team trust.

View your friendship as the place to practice tough things. So often we mistake friendship as the place where we should let each other off easily, look the other way, expect blind loyalty, hope for favors, or avoid hurting feelings. That’s all backwards. The closer we are to each other, the safer we should feel to practice flexing the relational muscles that help us both become better people. Our closest friends are the ones who know us best (Vulnerability), love us most (Positivity), and are most committed to us (Consistency), so those are the best places for us to practice such things as:

• setting boundaries

• asking for what we need

• sharing how their actions left us feeling

• giving loving, but honest feedback

• receiving feedback with the best of assumptions

• praising them when jealous

• giving voice to the unspoken issue we’re tempted to avoid

• disagreeing respectfully

• revealing our insecurities and doubts

• expressing pride for ourselves without downplaying our strengths

• negotiating for our preferences and needs

The list could go on, but the point is, if we can’t practice doing these skills with our friends, then what chance do we ever have of feeling more comfortable doing these important actions with our vendors, our customers, and our other team members? Our relationships are where we grow so if we’re willing to take on the joy of having fun together, then it’s also our responsibility to take on the Vulnerability of growth that comes with deep friendship.

This means we don’t make excuses for each other without asking some honest questions. Neither do we confuse loyalty for keeping someone in a role that isn’t working out. And we practice giving and receiving feedback, honestly meaning it when we say, “Do you think I read that wrong?” rather than practicing the defensiveness we might put up with someone we aren’t as sure has our best interests in mind. One of the best gifts we can give each other is the chance to role-play hard things that we each have to do in our positions.

The moral of the story: make sure our friendship is making us a better person, a better leader, a better contributor. Friendship isn’t something to hide behind but rather something to expand us.

Spend More Time Together Outside of Work and Leave Work Time for Others (Consistency)

As time and attention become our most valuable commodities in our relationships, it’s important that we invest them to meet the needs of our team and protect our friendship.

Focus mostly on others while at work: This isn’t to say we can’t connect while at work, but we want to be very clear that the last thing our colleagues want is to feel left out or concerned that the two of us act as a unit. We don’t need to sit next to each other in team meetings, eat lunch together every day, or be seen sitting for long periods of time in each other’s office. We’ll purposely mix with others at work parties, check in with colleagues about their weekends, and extend help to those around us. We remember that friendship isn’t an all-or-nothing game, so just because we’ve found one person we love being around doesn’t mean we don’t still invest heavily in those around us with our curiosity, authenticity, and kindness. These actions, from both of us, help protect our coworkers and contribute to a more positive workplace.

Spend time with your friend outside of work: As we become closer to someone at work, it becomes increasingly important that we spend more time with each other away from the workplace. Extending the invitation to connect at other times not only ensures that our bonding isn’t as visible of a threat to the team and isn’t on the company’s time, but it’s the best way we can protect our friendship too. If we want to remain friends after the job eventually ends for one of us, the chances to do that increase exponentially if we’ve already practiced spending time together away from the office. This will take our friendship to a whole new level, allowing us to see each other in different areas of our lives, giving us the space to talk more about new subjects, and hopefully eventually meeting other people who are important to each of us.

HOW TO NAVIGATE THE WORKPLACE WHEN WE’RE NOT GETTING ALONG

But what about when things inevitably go wrong?

The quote I chose to open my book Frientimacy was by Dr. Frank Andrews, who sagely said, “It seems impossible to love people who hurt and disappoint us, yet there are no other kinds of people.”1 It’s a painful realization that it’s impossible to be close to someone without also suffering from hurt feelings, unmet needs, and shattered expectations. And, yes, even our friends at work will annoy us, frustrate us, and leave us questioning their actions.

That doesn’t mean it’s an unhealthy friendship, or that our friend is selfish or toxic. In fact, depending on how we both respond to it, it can be the catalyst that leaves us feeling closer, safer, and more trusting of each other down the road. Think of close family members or romantic partners—we don’t feel safe with them because they’ve loved us perfectly the whole time, we feel safe with them because we’ve gone through hard things and still love each other on the other side.

But how to get there?

The First Step: Prioritize the Work

First and foremost, let’s remember we have two relationships in this one person: a friend and a colleague. And much the same way healthy parents continue to love and “coparent” their children even when they are fighting (even if what they are fighting about involves the kids), we will commit to “coworking” well together—no matter what. We don’t want the “kids” to suffer by speaking badly of the other parent, trying to get them to pick sides, fighting in front of them, or sabotaging the efforts of the other to care well for them. Even if a couple gets divorced and brings that romantic relationship to an end, they can still choose to be positive, contributing, and healthy coparents. Think of our work as “the kids,” and when we’re in front of them, they are our priority, which also means the other parent they love is our priority too.

TWO RELATIONSHIPS

In a moment we’ll look at how to reconcile as friends, but before that, and even if that never happens, let’s be clear with each other that we are mature enough to work well together as colleagues. That could include:

• Writing a short email or note to our friend that says, “I just want you to know that even though I am still hurt/mad, you can be assured that while we’re at work I will do everything possible to continue to support you.” Clarifying our good intentions at work not only deescalates the situation for future reconnecting as friends, but it helps set the tone for both of us at work to be more thoughtful.

• Or having that conversation together: “I know we’re both hurt right now and that we may not be quite ready to move on from this, but would you be willing to at least talk through what would feel best to both of us while we’re at work? What can I do, or not do, to make sure this doesn’t impact your job?”

• Choosing to blatantly support our friend at work to signal to them, and everyone else, who they can trust us to be during this incident. Whether that’s advocating one of their ideas during a team meeting, giving them credit in front of others, or offering to help on a big project—we will take the high road and prove to ourselves, our friend, and our team that we can be trusted.

• Refusing to gossip. It’s so tempting when our egos are hurt to try to win over some supporters who can take our side—even more so if we feel they’ve already heard “the other side of the story.” But to cater to our wounds in this situation just adds more wounds—both to our friendship and to our reputation. When we think we’re winning people over, we’re really saying to them that they can’t trust us to not talk about them someday.

The Ultimate Goal: Peace

We don’t have to know right now if we’re going to make up, break up, or simply move the relationship down the Triangle a bit. What we do know is that we want to feel peace.

And the way there is through our Emotional Intelligence (EQ). At its simplest, EQ is the ability to:

1. accurately identify what we’re feeling at any given time and

2. know what we need to do to manage that feeling and move us back to a place of peace.

Recognizing our emotions sounds easy enough, but the authors of Emotional Intelligence 2.0 report that only 36 percent of people tested can correctly identify their emotions as they happen.2 That means two out of three of us are walking around misnaming our emotions. Nearly all of us know how easy it can be to say we’re hungry when we’re actually bored, to say we’re threatened when we’re really embarrassed, or to say we’re annoyed when we’re simply tired.

I know, for me, when the stakes are high it can be hard to peel back the onion of emotions enough to honestly inquire, what am I really, really, really feeling? Often my first response, after being triggered, might be to claim I’m mad or frustrated as though anyone would feel the same way if their friend did X. But that’d just me being emotionally lazy. In my best moments, I can hopefully land more clearly: I feel dismissed because they didn’t acknowledge how important that was to me, I feel insecure because I don’t know if I can trust them to want my happiness, or I feel let down because I really wanted what they were offered. I may have manifested it with irritation, but what am I really feeling?

Most of us wish we had more clarity in our lives, and yet we routinely neglect the information constantly being dispatched. Emotions are our brain’s way of sending us a message to pay attention to something that matters; any mistranslation risks us not receiving the intended message. Far too many of us are walking around ignoring, or blatantly dismissing, the very memos that our bodies are helpfully wired to deliver to us. What are we really feeling in this fight?

After we can name our emotions, we can then ask a few strategic questions, such as: What information does this emotion give me about myself and what I need? Is there anything I want to do with this information right now that might be productive or positive? What wisdom is available to me about how to best proceed?

This is the second step of EQ: taking responsibility for managing our actions in such a way that we can successfully return to contentment, or happiness, as soon as possible.

The more clarity we had in naming our emotions, the more a strategy for response becomes clear. For example:

• If we really felt envy (wanting something that someone else has) when our friend didn’t invite us to lunch with another colleague but mistranslated it as jealousy (fear of losing something or someone to someone else)—we might be at risk of wanting to sabotage their relationship rather than admitting we wished we had been there as well. We now can respond in a way that increases our chances of being included next time as opposed to reacting in such a way that we lose them both.

• Or if we really felt unappreciated when our friend appeared to take all the credit on a project (or sale) but mistranslated that as feeling betrayed—we might be at risk of devaluing their legitimate contribution rather than inquiring what kind of recognition we need. We can now respond in a way that increases our chances of being seen as opposed to reacting in such a way that leaves our friend feeling unappreciated.

• Or if we really felt angry at them for crossing a boundary we said was important to us but mistranslated that as disappointment—we might be at risk of sulking and trying to get attention from others rather than confronting our friend to better clarify our needs and preferences. We can now respond in a way that increases our chances of healthy communication with our friend as opposed to reacting in passive-aggressive ways.

If we can take the time to self-reflect enough that we can identify what we’re really feeling then we can better ask, “What response increases the odds of me returning to a place of peace as quickly as possible?”

The best path forward is always to try to repair the friendship—especially so if this is someone we’ve loved, cared for, or felt close to. We can try. The best-case scenario is that we learn more about each other through this miscommunication and feel closer on the other side. The worst-case scenario is we need to move the friendship down a notch or two on our Triangle (no matter how personally we took something, very rarely do the actions mean the other person needs to be dropped all the way down!). There we lower our expectations a bit, grieve the loss of what we thought we had, and feel proud that we strengthened our relational muscles by at least trying. We’ll then remember that this is someone we still treat with kindness, clarity, and curiosity—staying open to what might heal and grow at future times.

Above all, we’ll see two different relationship roles here—the colleague and the friend—and we’ll clarify which relationship sustained the injury, so we can hopefully keep the other one as protected and safe as possible while we heal this one.

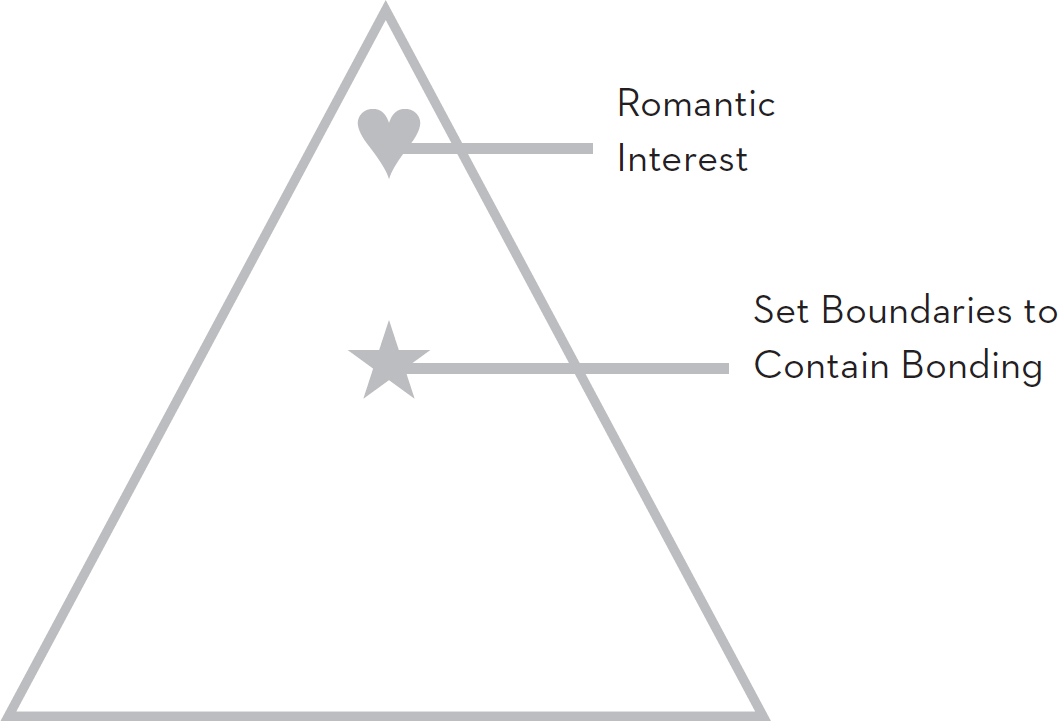

How to Protect Our Relationships from Unwanted Romantic Bonding

But just as some of us are afraid of fighting with a friend at work, some of us are also afraid of bonding too much with someone. There is perhaps no question with stronger opinions and more intense feelings than the topic of forming close friendships at work with the gender to whom we’re attracted. With more than 50 percent of women and 44 percent of men admitting they have had a “work spouse”3—a bond with a coworker that resembles that of a married couple but is purely platonic—the friendships are clearly happening. But that’s not to say we’re comfortable with it, at all. Especially if we’re the romantic partner of someone who has this close friendship. For just as the workplace is the number one place for friendships to start, it’s also the number one place where affairs begin.4 What makes it so hard, of course, is that the vast majority of affairs start off innocently with friendship as the only intention.

But as we now know, wherever there is Consistency, Positivity, and Vulnerability, so too will there be a bond. It’s impossible to work on a team with those three things and not feel close to each other. But this is where the Triangle might, again, be helpful. Seeing the progression of levels reminds us that perhaps the answer to whether we can be friends with people of the gender to whom we’re attracted is not so much a clear-cut yes or no across the board, as much as a “yes, but to an intentional degree.” For every story we hear of someone having an affair they swore would never happen, we can also find a story of two people maintaining and enjoying what they swear is a meaningful and completely platonic friendship.

Which is good news as we hopefully can get even better at maintaining platonic friendships with boundaries as we move further away from heteronormative conditioning that sees each other only as romantic, or sexual, interests. We not only desperately need more healthy cross-gender friendships in the workplace as we are all striving toward more equality for women (which includes mentoring, socializing, and friendships with men), but we also recognize just how lonely it would be to someone who identifies as bisexual if we believed they couldn’t be friends with anyone whom they might ever be attracted.

While this could be a whole book unto itself, here are a few guidelines I humbly offer:

1. We strive for the highest level possible of intimacy in our romantic relationship. Unfortunately, too many marriages and partnerships aren’t great examples of high Positivity, high Vulnerability, and high Consistency. We fall into patterns in which we hide parts of ourselves out of shame, avoid sharing things to minimize conflict, are too busy to really spend time together in meaningful ways, or have neglected all the actions of Positivity that leave us feeling close, including affirmation, enjoyment, empathy, and laughter. First and foremost, if we want to protect our romantic relationship from other bonds, we start by keeping that relationship as high on the Triangle as we possibly can—which also means having honest and loving conversations about all our other relationships. If we catch ourselves hiding something from them, that might be a warning sign we’re prioritizing another bond over this one.

2. We remember that attraction is not the same as action, that bonds aren’t all-or-nothing, and that we’ll inevitably bond with many people in many different ways. We’re healthiest and happiest when we have a full Triangle holding as many meaningful relationships as we can foster. While it’s a romantic notion that there’s one person out there who is meant to be our everything, the truth is that all of us are nourished in different ways by different relationships. Building a bond with someone else doesn’t mean we don’t love our life partner, that what we share isn’t special, or that just because we have room in our heart for more connection means that other connections are at risk. We will bond with lots of people in our lives to a varying degree of intimacy. And none of us are victims to how much we bond with someone—that is the result of the actions we take.

3. We ask the bigger question: To what degree are we comfortable bonding outside of a committed romantic relationship? This is a question all people will have to answer for themselves . . . hopefully with input from their romantic partner. For example, if we feel that the third level, familiarity, is as high up as we want a specific relationship to grow, then we want to be thoughtful to list what self-appointed boundaries feel best for containing the bond. In other words, if what moves people into the fourth level, commitment, are things like spending time outside of work, relying on each other for nonwork support, processing and asking advice about our personal relationships, or expressing our mutual adoration—we would be wise to clearly protect that line before we reach it.

One of my friends, Greg, whose best friend is a woman he used to teach with, has a rule called “Firsts and Bests” with his wife. Essentially, he not only makes sure she gets to hear things about his life from him first and gets the best of him, but it also means she gets first dibs on whether she wants to join him for a specific event; and she knows that certain actions (like buying flowers, in their case) is a gift reserved for her.

In a primarily male-dominated tech company, Amy and her fiancé have talked through a couple of strategies to help her strengthen her friendships in her field. Her fiancé joins her and her colleagues, as much as possible, for after-work drinks and rounds of pool with the stated purpose of “being her wingman” to help her have the chance to socialize and connect. In addition, they both agree that if there’s a coworker she ever feels some attraction to, she’d do everything she could not to spend alone time with him until the attraction passes. Their attraction-at-times-assumed approach normalizes that it will happen with hopes that admitting it can minimize shame and jealousy.

As there are so many different expressions of marriage, such varying degrees of personal maturity, and such distinct aspects of what would feel important to each of us, it’s impossible to give a clear list that would work for everyone. I always advise having a conversation with our romantic partners—even before there’s a specific friendship in question—about what we would each hope for, and need, when that situation arises. As one of my friends is good at saying, “It’s not that I don’t trust him, but I don’t trust the situation.” Let’s hold enough humility to realize that none of us are immune from feeling closer and closer to someone if we continue to practice the actions that create bonds.

With that said, unless you want to believe, and continue to reinforce, the disempowering caricatures that all women are out there trying to be temptresses and that all men are incapable of controlling themselves, it serves none of us to be scared of one another and make rules based on worst-case scenarios and fears. I’d love to believe, assuming I feel safe, that there isn’t anyone with whom I couldn’t ride an elevator, share a meal, or mentor. I obviously will listen to my intuition each time, but, in general, I will assume the best of others and trust my own wisdom.

WE ABSOLUTELY CAN DEVELOP HEALTHY BEST FRIENDS AT WORK

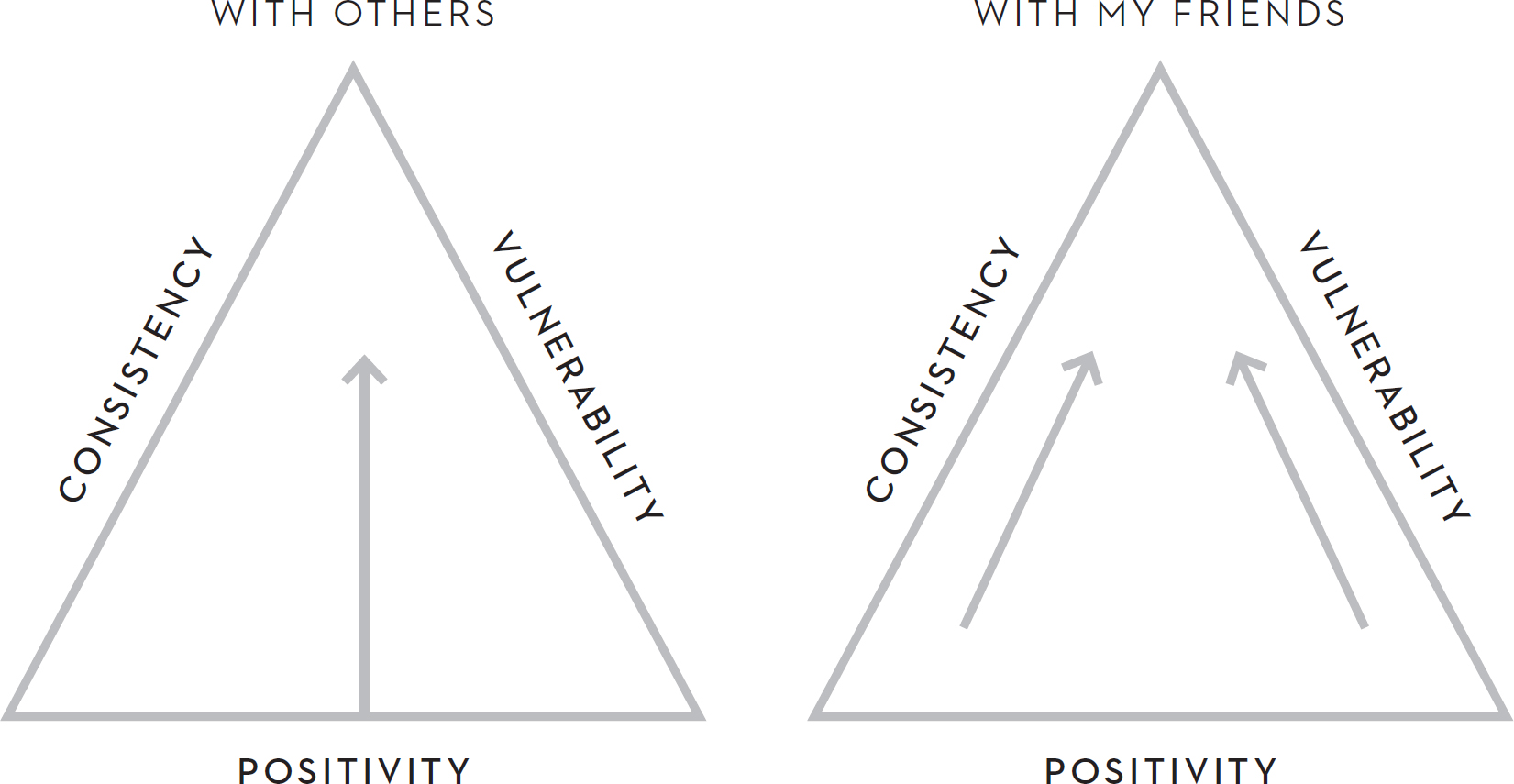

The details vary, but the support we feel from combining two of the most significant parts of our lives—our belonging and our work—can’t be minimized. There are millions of stories like Jennifer and Amalia. And if you want a closer friendship in your life that starts at your workplace, then I want it for you. Just remember, the three most important actions we can take as we deepen our own friendships at work are:

1. Positivity: Be extra intentional about expressing appreciation and kindness to everyone else around us.

2. Vulnerability: Increase our honesty to talk about our relationship and practice the hard things.

3. Consistency: Practice new ways of spending time together outside of work and leave work time for others as much as possible.

Hopefully more of us see the responsibility that comes with relationship. These connections, to be both meaningful and appropriate, aren’t just where we get to vent and get our own needs cared for, but they are also where we practice the skills that make us better people.