How to Develop Relationships at Work That Are Vulnerable

Of the Three Requirements, Vulnerability is undoubtedly the scariest one for most of us—especially in the workplace. When we think about encouraging it in the workplace, our brains conjure up images of employees crying in boardrooms, of employees gossiping and processing their personal drama instead of working, and of awkward trainings where we might all have to share our feelings.

But ask us what we want most from our coworkers and we’ll say things like:

• “I just want to feel appreciated for what I am doing.”

• “I want to feel safe sharing my ideas without feeling judged.”

• “It’d be nice to know my boss actually cared about me, as a person, not just as a means to an end.”

• “I wish I didn’t feel like I had to conform in order to be valued.”

• “I can see what we need, but no one ever asks me for my opinion.”

Then, ask the leaders and they’ll add to the list:

• “I wish I knew what my team really thought. Sometimes I’m afraid they just tell me what they think I want to hear.”

• “I think my team is capable of more, but that they’re so afraid of failure they prefer to play it safe.”

• “I often feel caught in the middle—feeling like I have to toe the party line and yet wanting to just be honest with them about what’s going on.”

• “I struggle between wanting to be closer to my team and worrying that then they won’t respect me.”

• “Sometimes I wish I was allowed to simply say, ‘I don’t know the right answer,’ without feeling like I’d look weak or incompetent.”

And you’ll see that despite our fears of Vulnerability gone bad, it’s actually Vulnerability at work that we desperately want. Not because we’re eager to come in and disclose our personal lives, but because we know how important it is to feel seen for who we are, even at work—or, maybe, especially at work. To that point, what continuously correlates with higher level of loneliness at work is how people answer the question about whether they “have to hide their true selves at work.”1 We want to be accepted for who we are. Work is not only where we spend most of our lives, but it’s where we’re making one of our biggest contributions. Why would we not want that significant side of us seen, recognized, valued, and accepted?

VULNERABILITY IS DEVELOPED

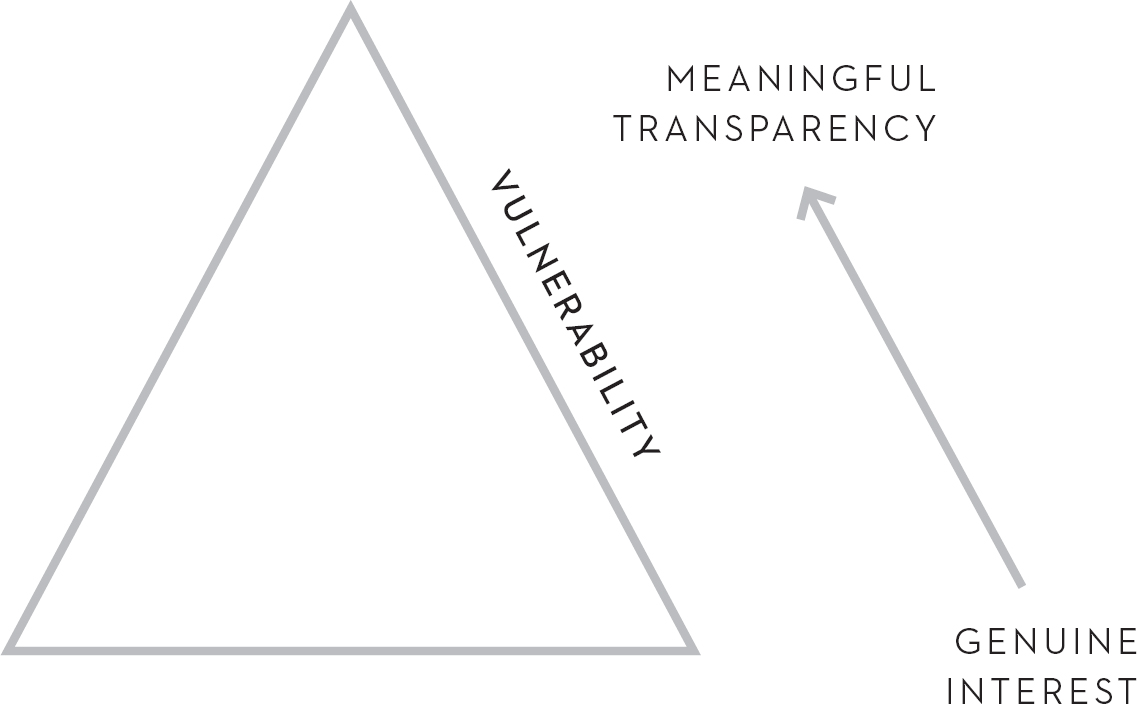

At the bottom of the Triangle, it’s not appropriate to confide and process our lives with someone with whom we don’t have a history of Consistency, but we can aim to be genuine in sharing who we are and be curious in learning more about the other. We won’t tell others everything about what we’re thinking, reveal our lives to them, or probe for juicy details—but we can aim to show up with authenticity in the context in which we’re connecting. At a bare minimum, we will show up with genuine interest—for who they are, in what we’re willing to share about ourselves, and for what this relationship could become.

The goal of Vulnerability is to get to know each other, which we do incrementally as we practice Consistency and Positivity with someone. When we’re asked what matters most to us in a relationship, most of us rank honesty at, or very near, the top.2 We want to believe that people are showing us who they really are, and we deeply want to believe we can do the same, without fear of judgment, exclusion, or punishment.

But, Vulnerability, perhaps more than Consistency or Positivity, is the one requirement our culture struggles with the most when it comes to “how much?” How honest should we be? How expressed can we be? How much of “us” can we show? How many of the details can we whisper? The Triangle provides us with the visual reminder that, again, it’s not whether to be honest, but to what degree.

Our goal is to be authentic in a way that is balanced by the level of relationship we have with someone. As we move up the Triangle, we will both practice increasing our Vulnerability in our shared context, eventually moving to sharing more in other areas of our lives, and slowly moving up to levels where we’re not only each sharing, but where we’re more likely to be processing our feelings, confiding our fears and shame, and shining proudly in who we are.

At the Top of the Triangle we experience meaningful transparency, both feeling that we either know everything there is to know about the other person, or at least that we’re willing to explore it together. Ideally, there is little need up there for filters, masks, or off-limit subjects because we feel secure in our commitment (highest level of Consistency) and complete acceptance (highest level of Positivity).

The most important thing is to keep in mind that there is a spectrum, a range of what’s appropriate to share and who needs to know what. We must work to find a baseline on which we can try to show up with as much genuine interest as any specific context calls for when interacting with most people. Then, with those who matter to us, we can hopefully move those relationships up the Triangle as we increase Vulnerability in conjunction with Consistency and Positivity.

HOW TO DEVELOP VULNERABILITY

Vulnerability, the willingness to lower our defenses and drop our protective armor, is the only way we will ever be seen. We might feel safe if we keep that smile plastered on our face, that polished image on our social media profiles, that commanding personality that makes people fear us, that poker face that leaves us feeling like we have the upper hand, or that ability to hide our feelings behind our jokes and laughter; but that pretense of safety comes at a huge cost of not really feeling known, seen, or understood.

If we want a high-performing team—either because we want to enjoy our time at work more or because we care about accomplishing our goals—then it’s not a matter of if we need more Vulnerability, but rather how we can create that “psychological safety” that is present in the best of teams.

In some ways, this might be the hardest chapter in the book to write, because “appropriate Vulnerability” will undoubtedly look very different in each of our contexts. A group of social work case managers might routinely end the day debriefing their cases with one another, talking about when they were personally triggered, and safely expressing their feelings. But it’s less expected that a group of lawyers would make the time to do the same, what with the valuing of billable hours, their likelihood of being out with clients, and being in an industry in which facts trump feelings. And while we can attest that lawyers represent one of the loneliest professions (so something probably needs to change), it’s beyond the scope of these pages to be able to determine what the ideal looks like for every industry, team, or culture.

But there are four guidelines I’d like to suggest, the first one filled with a long list of ways we could potentially practice Vulnerability no matter where we work.

Vulnerability Is More Than Disclosure

Vulnerability is not about everyone telling everyone everything. Not even close.

On the contrary, what we’re going for isn’t necessarily more disclosure as much as it’s more authenticity, empathy, curiosity, and courage. This isn’t about bringing more of our personal life drama to work as much as it’s about having the bravery to deal with the drama that is work. This isn’t about asking everyone on our team to reveal more as much as it’s about reducing judgment interruptions, and the fear of being embarrassed if we think outside the box. Vulnerability isn’t always about saying more as much as it’s about showing up more—showing up with honesty and hope when morale is down, showing up with courage and resilience when change is inevitable, showing up with kindness and clarity when hard conversations beckon.

Vulnerability is the remembering that we are human beings whose hearts and feelings not only can’t be shut off for eight hours a day but that we wouldn’t want them to be. We know that we aren’t our greatest despite our feelings, but because of them. Our Vulnerability is what allows us to celebrate our team wins, innovate creative solutions, empathize with our customers, and forgive our leaders for not living up to our expectations.

Vulnerability is the portal to feeling accepted, good enough, wanted, and valued. We want our vast experience to be helpful, our strengths to be appreciated, our ideas to be taken seriously, and our contributions to matter. For that to happen, we have to be willing to let those experiences, strengths, ideas, and contributions be seen. To feel accepted, we have to feel known; and to feel known, we have to reveal ourselves.

Examples of Vulnerability at Work

Brainstorming and Problem Solving. For many, this is one of the most vulnerable actions we can take—the sharing of our ideas. What if no one thinks it’s a good idea? Or worse, what if everyone goes in this direction, it doesn’t work, and I feel responsible?

In consulting various companies, I find myself in conversations all too frequently with employees who say something along the lines of, “It’s so frustrating because all he would have to do is . . .” Then a cascade of wisdom about what they wish their supervisor would do comes pouring out. To which I always ask, “Have you shared this with them?” Nine out of ten people say no. Oh, some will assure me that their boss wouldn’t listen or try to convince me it doesn’t really matter—they can just keep doing their job. But their venting behind the supervisors’ backs not only hurts the team that might benefit from that idea, but these employees are clearly frustrated and ultimately less engaged as they convince themselves that their ideas don’t matter.

One of the most powerful acts of brave Vulnerability we can practice is voicing our opinions and ideas. That doesn’t mean pushing them, fighting for them, or refusing to support other ways, but it does mean being willing to speak up when we see a problem and offer solutions when we can.

One manager of an internal communications team I worked with bravely, and vulnerably, led one team off-site meeting by asking all the people on her team to anonymously write down one problem they saw that they thought was either hurting the team or was a missed opportunity. She then wrote them all up on the whiteboard and facilitated a conversation about how these problems might be addressed.

As we build our relationships with one another, we practice “psychological safety,” which is the one most necessary ingredient on every high-performing team. We have to believe that we can say something without being embarrassed, dismissed, ostracized, or punished.

Celebrating, Cheering, and Pride. Vulnerability isn’t only acknowledging the shame we feel around our insecurities, but it’s also recognizing we have just as much, if not more, shame around our success.

Pride, like joy, is one of the feelings that brings the most Positivity, and yet it’s a vulnerable feeling that comes with guilt for far too many. Pride doesn’t mean we think we’re better than everyone, just as to feel inspired doesn’t mean we think we’re more inspired than everyone. We can feel pride, and should feel pride, and still celebrate and cheer for the success of others. True humility isn’t thinking less of ourselves, downplaying our success, or dismissing compliments; true humility sees how amazing we are and believes that everyone else is too. We don’t need more false humility in this world, and we definitely don’t need more people thinking less of themselves. We have big problems, and we need people who believe they can solve them. If Vulnerability is about being seen, then of course, we definitely want to be seen for our good too.

I routinely ask my friends, “Tell me something you’re proud of in your life right now.” I figure if we can’t practice being proud with our friends, then what chance do we have of showing up in the world with the confidence we need for facing the critics, the obstacles, and the fears? The workplace, in embracing more Vulnerability, has the chance to also shine brighter.

Showing Our Creativity. Sharing our creativity, in any form, is one of the most vulnerable acts because not only does creativity hinge so very much on uncertainty, but it can so often feel like a piece of us is on display, naked.

While some industries live in the world of creativity—advertising, performance art, music, fashion, research and development, media, and architecture, to name a few—creativity is a skill that is in growing demand across our workforce. A recent IBM study of 1,500 CEOs revealed that creativity is the single most important skill for leaders,3 and in a workforce preparedness study conducted by The Conference Board, 97 percent of employers said that creativity is of increasing importance.4

But we won’t have it on our team without practicing Vulnerability. Our employees aren’t going to volunteer that risk in a vacuum.

This was brought home for me as I recently facilitated an off-site meeting for a design team that scored high in Vulnerability. At first, I had been surprised because they all work remotely, which often isn’t correlated to high Vulnerability scores. And they had such diversity on the team that commonalities that might have helped them feel close weren’t immediately apparent. But, as Lee said, “Hey, when every week you’re each putting your ideas and designs in front of each other, knowing the end product will look nothing like what you are starting with, you have no choice but to be vulnerable.”

A couple things we can learn from teams that practice this skill regularly: the more you do it, the easier it becomes as you get less attached to any one form of your creativity; and the more everyone does it, the more likely everyone learns to practice empathy, Positivity, and encouragement as they all know what it feels like to have their work on display.

Responding to Conflict. It is not conflict that hurts a relationship, or organization, as much as our response to that conflict. The two most damaging responses tend to be avoiding the frustration and letting it fester in order to keep a façade of peace, or blowing up bombs of blame, shame, and anger.

The cost of ignoring conflict, in addition to the missed opportunity to learn more about each other and build the trust that we can solve problems together, is high turnover, passive-aggressive communication, a dysfunctional team, loss of productivity, and broken trust.

And I’ll guess that most conflicts we avoid aren’t some clear and obvious malicious monsters everyone on the team sees. Yes, there is bullying, blatant grievances, and palpable problems, but it’s frequently the less straightforward conflicts that we dodge: giving honest feedback to an employee, sharing our disagreement on the best approach to a problem, telling a coworker we took offense to his or her comment, or not expressing a need we have for our workplace comfort and effectiveness.

Jacob says that while he has a lot of good ideas, he hates “fighting about the best way forward, so it’s easier to just sit back and let everyone else figure it out.” To have people back down, wait and see, or simply withdraw is not only a massive loss of possibility for the organization and team, but it means one more employee who doesn’t feel seen. Ironically, it’s often the people who hate conflict the most who have the greatest superpower for bringing harmony to a team, if only they’d be willing to stay engaged and help influence the tone of the conversation.

Learning how to confront issues in mature and healthy ways takes incredible Vulnerability. We know what to expect if we just swallow our feelings (or go home and complain to someone else when we’re in charge of the narrative!), but we step right into uncertainty when we choose to engage. Vulnerability invites us to be less defensive, more present, and in touch with our feelings—all qualities that can turn conflict into connection.

Honoring Diversity and Inclusion. Diversity isn’t just getting our numbers right, it’s making sure we hear more voices, experiences, and perspectives. In other words, diversity for optics isn’t the same as diversity when we really see the unique contribution. But that takes Vulnerability, because we don’t know what we don’t know.

All too often we hire diversity because we love the idea of having new voices added into the mix, and yet in reality we don’t bring the curiosity that encourages those voices. To hire them means we may have to learn to do things differently. To welcome them means admitting our viewpoint isn’t the only, or the best, one. To hear them means we have to stop speaking and start listening. Those calls are all born from Vulnerability—that place where we don’t have complete control.

If our goal is for our employees “to feel seen in a safe and satisfying way,” then how can we ask questions in a way that assures them we not only won’t punish them for their answers but will appreciate their perspective? Are we willing to hear the answers to “What might we not see that you do?” or “What might you need that we haven’t thought of yet?” To ask this of our oldest and youngest employees; to ask this of people with different work styles, strengths, and personalities; to ask this of those who come from other countries, religious backgrounds, and political leanings; to ask this of the minority gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation; to ask this of those who have physical or mental challenges; to ask this of those who have worked primarily outside of our industry—this is what it means to value diversity.

Living with chronic pain, Peter expended so much energy every day simply trying to hide this truth. He downplayed it, minimized it, and tried to pretend it simply didn’t bother him. But when a friend asked him, “If you could change anything at work, what would it be?” it got him thinking how even a few hours of working alone in quietness every afternoon would feel like a game changer. His friend then responded, “That’s not an impossible request, you know.” An eventual conversation with his boss inspired her to ask everyone on the team that same question, which resulted in a lot of people feeling like their needs were taken seriously.

Jaysmine, an African American woman, says she just wishes that people weren’t so afraid of talking about racism at her workplace. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve watched us avoid the conversations we need to have because our senior leaders are afraid of saying or doing the wrong thing.” It takes Vulnerability to say, “We won’t do this perfectly, but we want to try. Will you help us?”

Our companies won’t benefit from the beauty of diversity until, and unless, we are vulnerable enough to let those diversified voices impact and change us.

Apologizing. Apologizing is a tricky business. It’s perhaps one of the most courageous choices a human can make, because it’s truly a lowering of our defenses. “We are wired for defensiveness,” says psychologist Harriet Lerner, author of Why Won’t You Apologize? “It’s very hard for humans to take clear and direct responsibility for specifically what we have said or done.”5

We don’t always know how the other person will respond. Will it lead to the outcome we hope for? What will they end up thinking about us? How will we feel afterward? Furthermore, most of us don’t even know how to do it well, when we should do it, or why. But apologies—recognition that we broke a social rule, unintentionally or not—can do more to repair trust in a relationship than nearly any other act of Vulnerability. An apology tells the other person we see them and their hurt feelings and that we care enough to want to reestablish better expectations.

But here’s the tricky part: the answer isn’t for all of us to apologize more.

Much has been said about women’s tendency to over-say “sorry.” We apologize for asking someone to fix what they messed up, for having a differing opinion, for taking someone’s time, and for expecting people to do their job. Vulnerability in many situations might mean being brave enough to take up space without apologizing.

Conversely, considering that our culture has not been stellar at encouraging, modeling, or expecting men to practice Vulnerability, it would make sense that those muscles probably aren’t as well developed. Lerner points out that while “in all cultures studied, men apologize less frequently than women,” it’s not because they refuse to do it as much as that they don’t think they’ve done anything wrong.

Gabriel lamented to me, “I honestly didn’t think I needed to apologize. I obviously didn’t mean to offend her and she tends to be overly sensitive.” But he said that watching the news of men in power refusing to apologize to people whom they’ve hurt softened him enough to try. The connection left him feeling greater respect for her and increased trust in their working relationship.

Whether we each fit those gender norms or not, the gift in Vulnerability is for each of us to be more reflective as we ask ourselves if we are more likely to hide behind our apologies or our defensiveness. But either way, our goal is to hide less.

And the list could go on. It takes Vulnerability to:

• Ask for help, support, or resources.

• Admit we don’t know the answer.

• Risk and reward failure.

• Share how we feel about a situation, conversation, or idea.

• Reveal our personal crises and disabilities when we need extra support.

• Be touched or impacted by the stories of injustice in our line of work.

• Tell someone about the inappropriate behavior we experienced or witnessed.

• Stand up for ourselves and ask for what we need.

• Resist conformity and value uniqueness.

• Try a new method, to experiment.

• Give and receive feedback without defensiveness and blame.

Hopefully, we can all nod our heads in agreement that our workplaces would be better off if we had more healthy examples of Vulnerability.

Vulnerability Inherently Comes with Risk So Don’t Wait for It to Feel Easy

We’ve got to realize that risk isn’t something to avoid, no more than we should try to avoid sweating when we exercise. When we want to push ourselves physically, we understand that sometimes that means gulping for air in a sprint, grunting through one more rep with heavier weights, or stretching a little further in our yoga move. We aren’t shocked when there’s discomfort, or even a little soreness. And the same is true for innovation, leadership, and personal growth: there’s no way to achieve it without awkwardness, a little emotional sweat, and risk.

Feeling uncomfortable isn’t a sign that it’s wrong, bad, or to be avoided; on the contrary, when we’re changing culture, learning new skills, and getting to know people in more meaningful ways, discomfort is to be expected. Even those of us reporting insecurity in our conversational skills, social anxiety, and shyness can’t allow those to prevent us from participating. We can pay attention to our energy to help inform us how we might need to engage differently, or more thoughtfully, but we can’t let it stop us. Even the most extreme introverts still need to be seen and feel connected.

Now the obvious caveat is that there’s a big difference between discomfort and an injury. The goal, as you’ll see in the next principle, is to train up to Vulnerability in such a way that we keep everyone as safe as possible. But to be clear: we won’t reach healthy Vulnerability without some anxiety, resistance, or heavy breathing along the way. What that means is that we don’t judge whether to practice it based on whether we feel fear or not. We will. Almost always.

Every time we choose to show up with authenticity, find the courage to voice our opinion, decide that we’re going to ask for what we need, or risk not conforming to groupthink or traditional culture, we will risk something. Sometimes it’s risking being misunderstood or judged; sometimes it may mean risking our paycheck, our reputation, or our brand.

We practice it because we value what’s on the other side: We value courage and innovation. We value diversity and inclusion. We value impossible solutions to our massive problems. We value love, acceptance, and hope. We value personal and emotional health. We value bold ideas, brave leadership, and high ethics. We value human connection and healthy relationships. We value feeling seen and seeing others. None, absolutely none, of these things are possible without Vulnerability.

To that point, I love the story that Dr. Brené Brown, the leading expert on Vulnerability, shares in Dare to Lead about asking one question to several hundred military special forces. Instead of spending her time trying to convince them that Vulnerability wasn’t a sign of weakness, she simply asked, “Can you give me a single example of courage that you’ve witnessed in another soldier or experienced in your own life that did not require experiencing Vulnerability?” And, of course, no one could.6

Vulnerability Must Be Practiced Safely

Similar to how we’d never advocate running a marathon without building up to it, Vulnerability is best practiced in incremental and escalating ways. In general, our Vulnerability should match, or be balanced, with our Consistency. The lower we are on the Triangle with each other—due to not knowing each other well, or because that relationship doesn’t feel safe due to lack of consistent behavior—then our Vulnerability will appropriately be low to reflect that. Just because we know Vulnerability is the way to connection doesn’t mean we want to be, or should be, connected closely to everyone.

As we increase our Consistency, feeling as though we have a structure, or pattern, for our relationship that feels reliable, we can practice increased Vulnerability. As we develop a history with each other of not being punished for sharing, we will feel more safe stretching what we can reveal or share.

In that study dubbed “The 36 Questions to Fall in Love” in which researchers validated that bonding had less to do with matching people up and more to do with helping them get to know each other, they found that the methodology with the highest success rate for consistently bonding people was “sustained, escalating, reciprocal, personalistic self-disclosure.” The best way to help build a relationship is to continue to share bits and pieces of ourselves with each other in an incremental and ongoing way.7 Not all at once, but bit by bit, we create a strong bond.

The Best Vulnerability Starts with, and Leads Back to, Positivity

But we don’t want just any bond. We want a positive bond that feels good to both people, and to the whole team. That’s why we mustn’t forget that while the two arms up the sides of the Triangle—Consistency and Vulnerability—must increase incrementally, they both rest on the base of Positivity.

Which, as a reminder, ideally comes before, during, and after anything we share with each other. In other words:

• We initially need something to feel good enough that we want to share something.

• Then, while we’re sharing, we’re looking for minor acts of Positivity to encourage us to keep sharing—whether that’s a nodding head, eye contact, sustained interest, appropriate reactions, or follow-up questions.

• And, after we share, when we’re at risk of feeling our most exposed—after the joke, the whispered insecurity, the exposed emotion, or the potentially silly idea—what we need more than anything is validation that we made the right decision to share.

It sounds so easy to validate someone for sharing, but I’ve encountered many Vulnerability hangovers that could have been prevented had a particular response been offered.

One of the most powerful ways we can transform culture is to become swifter with our positive responses. Every time we can thank people for what they shared, express affirmation for what they tried, or validate the feeling they expressed—we decrease the odds of them walking away feeling unseen or misunderstood, and we increase the odds of them feeling safer next time.

And when it’s our turn to practice Vulnerability, one of the best ways we can help others give us the Positivity we need is to encourage the response we most want. By saying, “Hey, I want to share what might be a harebrained idea with you, but instead of judging it, I’m hoping you could help me think through how we might theoretically make it happen,” we increase the odds of the support we want. We can respond to someone’s unsolicited advice with, “Thank you so much for trying to solve this, but honestly, what I think would feel better to me is simply your sympathy right now,” to hopefully spark his compassion instead of his fixing. We can get back on the sharing train after someone interrupts us or sidelines the conversation with, “Sorry, I wasn’t quite done sharing yet . . . hopefully you’ll give me a few more minutes of attention,” to invite her to better listening. We don’t have to walk away feeling unseen just because others aren’t reading our minds.

Granted, I know all of this can sound hard to do, if not impossible. But asking for what we need is at the heart of Vulnerability. To share something is one thing, but to admit it matters to us, and that the response of someone else can impact us, is perhaps one of the most vulnerable places to be. And yet, it’s through this portal that closeness and safety are developed.

Remind yourself of these two truths as often as you can:

1. Most people didn’t wake up today wanting to disappoint us or respond in any way that hurts us.

2. And most people haven’t been trained in relationship health, so they don’t know what they don’t know.

Both truths remind us that we don’t need to take their responses personally, and if anything, we just need to keep showing up with a willingness to model the contagious behaviors we hope to someday see from them.

VULNERABILITY IS REQUIRED

Our workplaces will benefit, as will we personally, if we believe we’re seen in a way that feels safe and satisfying. We can do that when we practice healthy Vulnerability:

1. Vulnerability is more than disclosure.

2. Vulnerability inherently comes with risk, so don’t wait for it to feel easy. It never will.

3. Vulnerability must be practiced safely in an incremental way in conjunction with Consistency.

4. Vulnerability should start with, and lead back to, Positivity.

Do we want a workforce that is creative, proud, authentically expressed, and diverse? Do we want a team that values one another, solves problems together, apologizes appropriately, and takes greater risks? Do we want to feel as accepted in our failure as in our success? Do we want to belong even if we don’t fit in? Do we want to believe we’d be supported if we go through a personal crisis?

Please say yes. I know it’s scary to think of “adding more Vulnerability” into our work, but all that really means is asking us to show up with courage, openness, empathy, and curiosity—things we already possess. Vulnerability isn’t “adding more” of something as much as it’s a refusal to keep asking us all to pretend that “less is better.” Compartmentalizing us doesn’t work. Fully human is who we are. Fully human is what our workplaces need.

We can see each other in safe and satisfying ways.

THREE WAYS TO INCREASE VULNERABILITY

1. Engage in “Small Talk” with New People. Few of us love trying to make conversation with people we don’t know well, and yet it’s the currency of connecting. It’ll be hard to get to meaningful stuff if we have nothing to build upon. So have a couple questions in your repertoire: an easy one: “So what did you do this last weekend?” a favorite one: “What got you into this profession?” as also, as perfectly suggested in an op-ed titled “The Awkward but Essential Art of Office Chitchat,” practice turning the “how are you” question into a conversation by sharing why you’re good: “I’m good. I just started a book/podcast/TV show and I’m really enjoying it. Have you heard of it?” Or mention something office-related, a shared common experience: “I’m good. They restocked the cold brew in the kitchen and it’s so strong. Have you tried it?”8

2. Clarify What We Need. Let’s tell someone what would be more meaningful to us or what behaviors we’d prefer. Instead of stewing, complaining, or venting, think of a situation in which we can try to practice telling someone what would feel better to us going forward.

3. Focus on Highlights and Lowlights for Deepening the Relationship. My favorite question with friends is to ask them to share one current success in their life and one challenge. This week at lunch, ask a friend to share how she’d answer that question!

THREE WAYS FOR MANAGERS TO INCREASE VULNERABILITY

1. Facilitate Personal Sharing. Maybe it’s gathering everyone up on Monday morning to check in with one another over coffee for twenty minutes, or paying for a weekly lunch when everyone eats together, or allotting some of our time during team meetings—whenever the time is, use it wisely for the purpose of some personal disclosure. Sample questions are available at www.thebusinessoffriendship.com.

2. Encourage Pride. We all crave feeling proud, and yet we often feel guilty for feeling it; so let’s help our team boost their confidence and normalize how important it is for us to take pleasure in our accomplishments. We’ll look for opportunities to tell them when we’re impressed with them, we’ll ask them to tell all of us what they’re doing this month that leaves them feeling the proudest, and we’ll help facilitate them in expressing when they see the accomplishments and contributions of one another.

3. Name the Uncomfortable. It’s easier to justify and make excuses, to look the other way, and to hope that conflict and hard emotions simply resolve themselves. But we’ll see those as opportunities for us, and our team, to practice our Vulnerability. Then we’ll be the ones to ask, “What are you feeling right now?” when we sense a mood shift; “Is everything okay between you two?” when we pick up on tension; “What do you need right now to feel peace again?” when we know someone is stuck; and “What’s the hardest part of this for each of you?” when the team is facing an obstacle.