1960

It is an ordinary evening of a school day in Edinburgh, and I am spending the evening at a friend’s house. Her mother sits in an armchair near us in the sitting room, knitting and watching the news. The worst place to be in the world is the Belgian Congo and images unfold of African bush and simple mud houses along dirt streets. The presenter speaks a warning and her mother sends us from the room since the news report is too shocking for our tender ears and eyes. This is a novel turn of events so immediately on full alert; we sit outside the door trying to glean information. We don’t discover much, but our appetites have been whetted and we take to reading the papers about horrific tales of rape, murder, and cannibalism of priests, missionaries and nuns. The thought of the nuns at school being eaten is something to ponder.

That same year The Congo gained independence from Belgium’s particularly harsh administration. On that first independence day in June, Lumumba the first president before Mobutu’s coup, proclaimed:-

‘Our lot was eighty years of colonial rule … We have known tiring labour exacted in exchange for salary which did not allow us to satisfy our hunger … We have known ironies, insults, blows which we had to endure morning, noon, and night because we were ‘Negroes’ … We have known that the law was never the same depending on whether it concerned a White or a Negro … We have known the atrocious sufferings of those banished for political opinions or religious beliefs … We have seen that in the towns there were magnificent houses for the Whites and crumbling shanties for the Blacks, that a Black was not admitted in the motion-picture houses, in the restaurants, in the stores of the Europeans; that a Black travelled in the holds, at the feet of the Whites in their luxury cabins.’

17th November 1970

The country we had tried so hard to avoid and then struggled so hard to enter was the source of our greatest fears in the whole trip. Crazed cannibalistic rebels apart, one of the cruellest colonial regimes in Africa had existed here and the Congolese owed Europeans no favours.

Relief at arriving relatively unscathed after our recent ordeal, mixed with apprehension at how we’d be received. Tall grasses brushed both sides of the car and we cautiously proceeded. A muddy red track unused by any vehicle bigger than a bicycle for years, twisted between lush green vegetation leading us to our fate. Ross stopped the car.

‘I don’t think we should risk it. I’m going to get rid of it and throw it away.’

With that he took the gun out of the glove compartment, walked to the edge of the forest and performing a wide overhand throw dispensed of our weapon far into the greenery.

‘After the reaction of the customs officers when we entered CAR I think we’d just be inviting trouble if we kept it, especially if we didn’t declare it and then they discovered it.’

He climbed back into the driver’s seat and I felt a weight lift from my shoulders. We continued another hundred yards to the junction with a better-frequented road and approached a tiny hut marked ‘Douanes’ with a clear conscience ready to meet our first villainous Congolese customs officer.

The simple customs house stood alone in a clearing behind a flagpole with chickens pecking around outside its mud walls. We parked in a shady spot, gathered up our papers and stepped inside trying to look inoffensive. Under a framed picture of President Mobutu with signature heavy glasses and toque perched on his head, the officer shook our hands and welcomed us to his country. His clientele would normally be local travellers on foot or bicycle. We couldn’t imagine many other vehicles venturing up that dust track to keep him busy and his spruce appearance and efficient manner took us by surprise. He spotted that the carnet had been wrongly dated, something that customs officers in eight other countries had failed to notice. We expected a bad reaction and watched nervously waiting for him to grasp the opportunity to bribe or fine us. He shook his head at the careless blunder made in London showing a start date after the termination date, altered it with black pen and then requested some aspirin.

‘It’s hard to get hold of medicine in our small village,’

I translated his words to Ross, and like some fawning peon went to fetch some pills, grateful and relieved at such a small request. We suspected that our first aid kit’s reputation had run ahead of us, and gladly handing over a handful of aspirin we were free to go.

Sixty miles further up the road at Monga we knew that the immigration officer would have closed his office for the day so we stopped to rest. We watched Congolese walking or cycling along the roadside and going about their daily business. They were just like other Africans but as many as a third of them had enlarged thyroids. Deep in the forest a thousand miles from the sea there must be a lack of iodine.

18th November

Ours was the only vehicle travelling over the red mud. We climbed a gentle incline while the forest dripped around us and hid rustling secrets. Something moved on the road ahead and I peered through our insect-stained windscreen to see. A small troop of man-sized gingery monkeys looking like orang-utans but much hairier, heard our approach and within three seconds had disappeared into the tangle of greenery to either side, scooping up their babies as they scrambled to safety. The sight we hoped to catch at the spot where they vanished eluded us, while they probably had a good look at us from the leafy shadows. Our hopeful eyes strained for other wildlife sightings without reward until the immigration office distracted us with practicalities.

Again anticipating trouble at immigration we approached the office with friendly diplomatic smiles pasted onto our faces and again all went smoothly. We left with less trepidation than before. The people reacted to us the same as everywhere else and the trouble we had expected at every turn didn’t manifest itself. At first they looked unfriendly and suspicious of two foreigners in their strange car, but it only took smiles and waves for their whole expression to change as they reciprocated our friendliness.

By nine o’clock we arrived at another river, but this time a pontoon was in operation. The floating platform would be hauled across the river by ropes, and looked a much safer vessel than the raft of our recent adventure. We didn’t mind waiting in the least after our experiences over the last twelve days and felt like ‘old hands’.

Two pale girls also waited. They stood out like beacons amongst the smiling black faces. We guessed they had something to do with a mission, probably the American Baptists. Silent and joyless in their teenage years their mousy hair hung lank under straw hats to frame faces deprived of sun, a commodity not in short supply. Shapeless pastel cotton shifts covered thin shapeless bodies revealing nothing of arms and legs. Off-white socks hid ankles above cheap canvas shoes. I tried to catch an eye to say hello, perhaps enjoy a customary exchange of experiences. Not a flicker betrayed any willingness for social contact. This was a strange meeting of young white women in the heart of darkness.

A large wheel was fixed to a sturdy tree at each side of the crossing, with thick rope attached to each end of the boat. The rope went around each wheel and hung like a taut washing line above our heads. A shout from the man in charge prompted three others to heave on the forward rope and pull us closer to the other side. Ours was the only vehicle on board, and timings of crossings corresponded to the number of passengers and the workers inclination. We looked forward to a free passage across the swirling water which was only fifty yards wide but half-way across the ferrymen asked for presents. We parted with a few cigarettes and aspirin, a gift proportionate to effort and goodwill. They thought us mean but returned to their heave-ho, not in the mood for mutiny.

Bad roads followed but not as drastic as before until about five miles from Bondo when we met two young American men whose Jeep had skidded off the road into a sea of mud. We did our best to tow them out but even with the help of our ladders the task needed the power of a truck not our townie saloon car, and we risked pulling ourselves in with them.

‘We’ve come from Malawi and are heading for Mali,’ said Gary, ‘how about you guys?’

They had journeyed up from the south of the country through Kisangani. This was not their first problem with mud, and they were not the first people to advise us to stay on higher drier ground.

‘You wouldn’t believe the state of the roads back there,’ he said. ‘It’s the trucks that make it worse, and there doesn’t seem to be any maintenance programme, at least not during the rainy season. It was tough enough for us in the Jeep; you wouldn’t have a hope in that car!’

They planned to cross the border at Bangui as we had originally planned, and were interested in our alternative route. We didn’t fancy their chances of arranging a raft- crossing from this side of the river with a much heavier vehicle, and left them to make their decision.

‘Is there anything else we can do to help before we go?’ asked Ross after we’d failed to pull them out.

‘Well you could send someone out for us. We stayed at the Catholic mission in Bondo last night, it’s easy to find. Ask for Father Aloysius, he should remember us. If you tell him our situation he’ll know what to do. Just say Gary and John sent you.’

‘You stayed at the mission?’

‘Yeah, you should do the same. It’s not safe in this country after dark, and the police and army are not to be trusted, never mind the bandits. There are plenty of missions to choose from but we find the Catholic ones are the best. They make a small charge to cover their costs, oh and sometimes they’ll give you breakfast and dinner as well!’

No rain for two weeks made for reasonable driving conditions and we hadn’t realised how lucky we’d been until the heavens opened. We hit a wet patch as slippery as an oil slick carrying us careering sideways into a ditch. Luckily the car fared better than our nerves. Still shaken Ross stepped out and skidded as badly as the car, ending up on his back. Trying not to laugh at his slapstick performance, I helped him up. We clung on to branches to prevent another fall, manoeuvred the ladders, and got the car back on to the road. Cleaning up effectively was impossible and the reddish-brown slime carried back into the car with us on clothes, sandals and worst of all the ladders did nothing to enhance our living conditions. Since I still had to exit and enter through the driver’s door the mess spread badly, but it dried out in time and the worst could be scraped off.

At Bondo we tracked down Father Aloysius to report the message from the two stranded Americans. He set out immediately with a small truck and a length of sturdy rope. We felt part of the ‘bush telegraph’.

The ferry for crossing the next river was not in operation and it looked as if we might have to cross on dug-out canoes again.

‘When does the ferry leave?’ I asked a passing African.

‘Ne sais pas.’ The African shrugged. He didn’t know.

As in Bangassou every reply to our enquiries gave no, or at best vague information. This time unfazed by the prospect, we accepted the possibility of raft-building with resignation and decided to leave it until morning. It was pointless to fret about something over which we had no control, and our main worry would be the cost. Within two days we had accepted this mode of river crossing for our nearly-new car to be normal practice.

Meanwhile the petrol gauge had dipped dangerously low so we explored the town for supplies. Purchasing fuel didn’t involve anything as modern as a petrol station. Instead we had to visit ‘Comaco,’ a contracting company which had fuel supplies for their own trucks. Few cars existed or survived in the small town and most people relied on bicycles. We arrived at a fenced store and parked outside.

‘Nous cherchons l’essence,’ I explained to a man in oily overalls.

He nodded and led us over to a small stack of forty-five gallon oil drums. One of them was fitted with a hand pump. He quoted a price and we returned to the car for jerry cans. We filled them with his help and in turn lugged them back to the car parked outside the gates, pouring the fuel into the tank. An extra two cans were filled as spares as supplies could be scarce in this country, paid and headed back to what passed as a town.

To fill ourselves up we found bananas and mangoes in the market, but for the first time since leaving home we couldn’t track down any bread.

‘I think we deserve a beer,’ said Ross.

‘That’s a good idea;’ I replied, ‘I don’t think I can face any more chlorinated water today,’

‘I wonder if you can buy it here.’

In the town’s only small shop we had found the usual tinned sardines, corned beef, and basic bags of flour, sugar and maize meal but no cold drinks of any description, so we stopped a man in western dress to ask. He directed us to a nearby house. Thinking there had been a mistake we asked someone else and got the same reply with the added information that it was the doctor’s house.

Puzzled, we climbed side steps up to the first floor of the house, feeling like trespassers. A balding bespectacled man inched open the door.

‘Excusez moi, on nous a dit que vous avez de la bière,’ I ventured.

The smiling and somewhat bemused Belgian doctor insisted on inviting us in. He produced three bottles out of an ancient fridge and we sat down with him in his bachelor-status sitting-room diverting him from work. A desk in the corner was piled high with papers abandoned with our arrival. ‘Santé,’ said the doctor looking glad of an excuse for a break. Our payment would be to regale him with our experiences since leaving UK.

We returned to the mission to see if we could spend the night and take a badly needed shower. For a voluntary donation we were offered an evening meal and a room for the night. There was no shower but a monk brought us a fresh jug of hot water in our ‘cell’ for washing in Victorian style, placing it on the small wooden table next to an enamel bowl. We could use the visitors’ lavatory down the corridor.

Alongside silent monks we sat at a long refectory table watching the others for clues on the form. After Ross tried to make conversation with his neighbour, a senior monk intervened and told him that Brother John would not reply because like most of them he had made a vow of silence. The senior monks were exempt allowing them to manage the place. After grace the abbot talked to us while the others sat mute, passing dishes of small potatoes and stringy spinach along the line with a nod or half a smile. The small chunks of meat were wild boar and so tough they had to be swallowed in their entirety, but leaving any was unthinkable. I wanted to know who had caught the animal, and how; what other bush meat was available to them; did they raise chickens; and how much they grew themselves. But answers were not available in this conversation-free zone for such trivial exchanges so I kept my questions to myself.

Ten of their missionaries had been murdered six years ago, and the few survivors had all returned along with compassionate new recruits eager to restore some sort of order. Local people had suffered far worse at the hands of the rebels from beatings, rape, torture and ritual murder. Their homes, families and lives had been devastated and the monks offered humanitarian, medical, and spiritual support. Now things were slowly returning to what they called ‘normal’.

At half past eight a key turned in our door and we felt like prisoners. Sleeping indoors rather than in the car had been a luxury every other time we’d done it and I was looking forward to the same in spite of it being called a ‘cell’. We had half an hour before the noisy generator would be switched off, and all the lights with it.

The Abbot had given us the choice of one or two rooms and we’d opted for one. Our single bed was a concrete slab covered by a thin mattress and we soon discovered that comfort was impossible, let alone intimacy. It wasn’t long before Ross opted for the floor as a more comfortable option for us both as it was only a little harder than the bed but without the risk of falling off. Neither of us slept well because of the cold, which was the price of keeping to a route at higher altitude. We’d been given one thin blanket, and being locked in couldn’t go to the car for more clothes or our own lovely blanket. My mosquito bites kept me awake and by now my feet and ankles had swollen up badly with bites scratched too often during my sleep and becoming infected. I got up to dip a cloth into the water-bowl for dabbing at the hot red mounds. It helped for a while before I succumbed to scratching again, which would be to my cost later in the trip. A cockerel with a bad sense of the hour started to crow at three in the morning and with uncanny timing crowed again just as I had nodded off. He kept this up until dawn.

19th November

It was a relief to get up at six, and then we found that the time zone had changed shrinking the day by an hour. We drank black coffee and ate thin slices of homemade bread and pineapple jam for breakfast as silently as the monks but without their company. They’d been up since before daybreak, courtesy perhaps of the cockerel.

Neither of us could summon up much energy to arrange a river crossing, but we went through the motions. The same lack of reliable information surrounded us again like fog. At Comaco where we were looking to organise another raft, we met a Greek called Andreas who took us back to his shop to change a traveller’s cheque. He offered us a good exchange rate and a beer. Perhaps he’d spoken to the doctor, but beer and mornings don’t go together in my experience. It was good to talk, albeit in French, after the stilted conversations of the night before and this man had useful information. The road between Buta and Kisangani was virtually impassable and he wouldn’t even attempt to take his trucks through. Looking for a detour we brought out our map to make a plan.

Meanwhile it transpired that a new Monsignor was arriving on the opposite riverbank at midday bound for the Catholic mission. Consequently all efforts had been made for the VIP and the old ferry would be repaired by 11.30am when we could cross. Relieved of the task of organizing another river crossing we spent the rest of the morning chatting to Andreas and he produced more cold drinks and salami sandwiches. We got on to the subject of bushmeat and wild animals.

‘There are many wild animals here,’ his eyes sparked at the thought. ‘I would like to show you something, but you must tell no one. Do you promise?’

We nodded, intrigued. We finished our drinks and followed him outside. Plenty of game could be found nearby, and sworn to secrecy, he led us through tall grass on a narrow path for half a mile. We didn’t see any animals and assumed they were hiding in the dense bush, but arrived at a large wooden shed the size of a single garage. A heavy padlock and chain secured the double doors which he unlocked, looking over his shoulder and scanning the bushes for inquisitive eyes.

‘Et voila!’ he announced proudly. Packed from floor to ceiling were piles of elephant tusks. The biggest ones arched up to nearly touch the ceiling, and dozens of smaller ones wedged them in. It was a miserable sight. He boasted about the biggest ones and how big and old the animals had been. His shed load of ivory was worth a fortune on the black market and in a land devoid of proper controls he would probably get away with it. It was a struggle not to show disapproval to our kind host

‘Here, you can have this one as a souvenir,’ he offered generously.

Ross held up the small tusk to admire, and then passed it to me. A hollow centre ran halfway down the curved length where it must have been attached to the soft tissues of its victim. I visualised its bloody removal from the beast and shivered.

‘We would have trouble at the customs I’m afraid,’ said Ross.

‘Yes that’s true, but you can easily hide it in a corner of your car,’ insisted Andreas.

‘Thanks, it’s very kind of you,’ replied Ross, ‘but we’d rather not take the risk.’

At 11.30am we boarded the ferry which was another pontoon. Although the jetties at either side of the river had railings, the platform itself had none. It was nothing more than a bobbing raft, but too big to be held still as the paddlers in Bangassou had done. Ross boarded with supreme caution, and I stood on deck to attempt guidance.

The crossing was a miracle of precise timing we had learned not to expect and we arrived safely on the opposite bank before midday. To welcome the Monsignor a large crowd had assembled by the river, singing hymns in rich African harmony. Glorious arrangements of brightly-coloured flowers adorned the jetty and I wondered where they came from since all I’d seen for weeks was leafy growth. What a lovely impression the Monsignor would get of life here!

We’d been warned to expect the worst on the road to Buta and it lived up to its reputation. We were forced to stop several times in the full range of mud, deep pot-holes, rickety bridges, and sand that had become part of every journey. We thanked our lucky stars that the ladders always helped us out.

The travellers’ code we’d discovered in the Sahara also operated here for Europeans. A Belgian who stopped to chat told us we could get entry permits for Uganda at the frontier with the Congo so there was no need to go to Kisangani on the dreaded road. This was the one that the Australians in their Dormobile and the Americans in their Jeep had told us was virtually impassable.

It wasn’t only us who gained from these impromptu exchanges; we brought a taste of Europe to far-flung outposts and found ourselves eagerly invited into discussions.

‘That’s the best news we could get,’ I said to Ross as we drove on. ‘I didn’t fancy our chances on that road, or even a detour!’

‘No, neither did I. It sounds suicidal to use that road, so I’m glad we’ve been let off the hook. The only problem is the increase in mileage by going round East Africa. I’m not sure we can fund the petrol so we’ll have to do some calculations and maybe get some more money sent out if necessary.’

This last possibility was one we’d move mountains to avoid, as it would involve pleas to our parents and admission of failure, if only of our budgeting.

Repeatedly freeing the car from muddy situations had us covered in grime, slime and sweat by the time we got to Buta. We made a roadside stop and tried to make ourselves respectable with flannels, cold water, combs, and a change of tee shirt, but the mud still clung to our sandals and under our fingernails. To cheer ourselves up we succumbed to another glass of beer.

At eight o’clock we headed for the mission but everyone had already gone to bed and the main gate had been padlocked, so we parked just outside the grounds. After the previous night I can’t say I was disappointed!

20th November

Looking for bread again we had no luck. Everyone seemed to bake their own and no one had any to sell. There was another Comaco depot in town, so we stocked up with petrol and then set off on the detour to Isiro. It was a higher road deemed to be better than the main one since it had suffered less in the recent heavy rainfall. We found the alternative route slow and tiring, so realised that our chances would have been slim on the other road. The car took many bumps because we couldn’t judge the depth of pot holes under the puddles, and we soon had another puncture.

The forest spread dark and tall around us with shafts of sunshine struggling to dapple the leafy floor. While we changed the wheel the usual crowd gathered. Amongst them were pygmies, mainly men but also two women standing chest-high beside the other Africans watching. They giggled at us as Ross heaved a spare wheel from the back seat and I helped to loosen the flat one with a wheel wrench. Ross lifted the bonnet to inspect something and instantly shadows fell over the engine from numerous woolly heads bent over to see inside. Not wanting to spoil their entertainment I found Ross a torch. As we all looked into the engine, I felt a slight tug at my hair and turned to see one of the women looking guilty. She’d been feeling my hair to compare with her own, and might not have seen hair my colour before. I held out a lock and invited them to have a better feel, and grinning they all reached fingers forward. We had their full attention, and as we finally drove away on the fresh wheel, they all waved enthusiastically and laughed behind their hands. We could have been a travelling circus put on for their amusement.

Further along the road a snake slithered across the damp red track disturbed by our engine’s rumble and later a badger lumbered bear-like away from our noisy approach into the shelter of dripping vegetation.

Ten miles short of Baranga we’d exhausted the energy needed to reach the town. The drudgery of constantly freeing the car from difficulties, and with constant shaking and bumping when we were in motion had taken its toll. We stopped unable to go on. Somehow we felt safe enough to spend the night on this little-used road, and were too tired to care or even miss the comfort of a bed. Before dark a flock of birds descended on a nearby tree and I remembered the swallows in Algeciras five weeks earlier. They would be in South Africa by now. Their route took them over the Sahara too, but from Nigeria they could fly due south without our restricting need for dry roads and visas.

21st November

We had run short of food and tried again to buy bread. In a shop at Baranga the lady shopkeeper gave us some of her own, it was not for sale. We still had a tin of condensed milk to make a sickly but energy-giving sandwich.

The roads didn’t get any better and loud creaking noises were emanating from one of the back shock absorbers. Perhaps it had absorbed one shock too many. An investigation found that one of the rubber stops which had been welded back in place in Lagos, had fallen off, and now the other one had loosened. Without their protection the back axle had punched holes in the chassis of the car through repeated hammering from dreadful roads. To prevent further damage Ross had to drive more carefully and on roads full of pot holes our progress felt like snail’s pace.

Most of the bridges we came to looked perilously close to collapse. The first dilapidated crossing made us stop to stare at it in disbelief. Gaps, through which our wheels could easily fall, had to be bridged by the sandladders and this became the formula for the next few bridges too. Ross crossed over each one at a snail’s pace.

The ladders came in handy again when we were stuck in mud. A man who’d stopped to help was thrilled when Ross gave him the ladder we’d just used. We only ever used one at a time and it gave us more room inside the car. They had made a horrible mess of the seats, scratching the upholstery and leaving ingrained stains.

At four o’clock we arrived at Isiro and went straight to the mission hoping for a badly needed shower. A cool reception, possibly due to our unkempt appearance, prevented us from returning at a more convenient time for further enquiries. Instead we stayed dirty and went into town for petrol and a mechanic.

We met some friendly young Greek men who told us where to go for car repairs, and instructed a small African boy to take us there. The manager of the garage, another Greek called George, spoke good English. He promised to help us the next morning. We chatted for a while and soon beer was on offer along with a room for the night which we gladly accepted. Living and travelling the way we had been made that cold beer taste like nectar.

Greeks had established communities in the Congo before Belgium claimed it for a colony. They held a strong presence all over the country, setting up businesses in coffee, trade, fishing, and transport but stayed out of politics and kept their religion to themselves. They were survivors and only concerned themselves with commerce.

We went into town to buy some bread, successfully at last from a Greek baker, and then ventured into a building calling itself a hotel. We started to feel human again as we sipped cold drinks and our taut nerves relaxed. We were still lingering on the sweat-stained armchairs after nightfall, listening to the chanting of the cicadas and marvelling at being in the depths of Africa. Wanting to hang on to our upbeat mood we stayed on in the shabby establishment for a proper meal, leaving the bread for later. George came to find us and took us back to spend a very peaceful night with the luxury of a bed each that wasn’t made of concrete.

22nd November

Breakfast was coffee and a ham sandwich, another treat for us compared to chlorinated water and bananas squashed onto bread if we were lucky. Work started on the car an hour later.

They glued one rear-suspension bump stop back into position and replaced the other with a part salvaged from a wrecked Dodge. Thousands of miles of awful roads had given these protective blocks a machine-gun hammering, starting with the Saharan piste, and it was a miracle that the leaf springs hadn’t broken. Another fist-sized hole in the chassis was welded. Oil, water, brake and clutch fluid levels were all topped-up and our long-suffering car was once again ready for its next onslaught. The wheel alignment could have done with some attention but would have to wait.

The next two days would bring local festivities to celebrate the anniversary of Independence. Like our New Year it would involve the consumption of copious quantities of drink. The Greeks advised us against passing through the Congo customs until three days hence by which time the effects of alcohol would have worn off. Having already suffered at the hands of drunken officials we welcomed the chance for a rest, and celebrated with a long overdue wash.

Late in the morning our hosts left to visit one of their coffee plantations, and we waited until early evening for their return. There was nothing for us to do or organise and the enforced rest was bliss. The cook would prepare dinner for us – roast beef, beans, salad and chips – a feast that brought reality to some of our hungry fantasies. Their kindness knew no bounds, and when we left they refused payment for the work done on the car.

We managed about thirty miles on bad but not impossible roads with the only distraction and diversion being around an enormous spider about the size of a child’s hand sitting in the middle of the track. We poked the poor thing with the end of an umbrella and luckily for us it didn’t retaliate.

23rd November

Sleeping in the car again came hard after the comfort of a proper bed, not least because of invading mosquitoes. We stretched limbs stiff from an uncomfortable night, washed out dry mouths with the hated chlorinated water and set off. Big trucks had not used the roads we were on, so driving wasn’t too difficult in the absence of deep ruts. When we felt hungry we looked for a market but all trade had stopped because of the holiday. An old man carrying a branch of bananas was making his way up the road so we stopped the car and walked back to him offering to buy some. He looked threatened and backed away. We tried to gesture friendship but he kept hurrying away, and finally cried out something which sounded pretty desperate so we gave up and left him in peace.

Later we had more success in a village where an eager young man disappeared for a few minutes then emerged with an enormous branch of very ripe fruit. The bananas were falling off as he walked towards us. Because of language difficulties it seemed easier to buy the whole lot, but we doubted if we’d get through them all before they rotted. We could manage on banana sandwiches for at least one day after the good food in Isiro.

Ten miles from Faradje we had to slow down for a tribe of Vervet monkeys sitting in the road. They had strayed from nearby Garamba National Park. Continuing into the town we met up with the young Greeks from Isiro again. They had been visiting the game park and enjoying a break from work. We drove on to Aba.

As usual our first thought on arrival was a cold drink, so we asked for directions to the hotel. We parked outside and I was preparing to clamber out of the driver’s door in my customary undignified fashion. A van drew up beside us and the European inside told us there were no cold drinks at the hotel, but to follow him.

No longer surprised by this welcome, we arrived at Costas’ house, missives were relayed to the kitchen, and a small but mature Congolese cook wearing an apron appeared with a tray of strong Greek coffee, some creamed rice and cinnamon, and apples. Japhet padded barefoot across the red polished concrete floor on broad dusty feet. He bowed as he laid the food down, and backed away from the table respectfully. A few minutes later a stream of invective drifted out from the direction of the kitchen. In his own territory the humble servant was loudly wielding his power over his own underlings.

Conversation became easier with everyone speaking English, and we were delighted to accept a room for the night. We sat around a huge sitting room sparsely furnished but with worn upholstered armchairs for everyone. An enormous snakeskin stretched nearly the height of the room at its middle. It continued the length of the wall and tapered to a point at the end of the adjacent one.

‘I shot that python five years ago,’ said Costas, ‘It measured a full ten metres.’ He added proudly. ‘It was only about six steps from our front door, and when we cut it open there was a whole goat inside its belly.’

Later George’s nephew, who we’d met in Isiro, appeared and we talked away the afternoon about travelling and living in Africa. The repair to the bump stop that had been done in Isiro had loosened again, so Ross also discussed with him the options for a temporary fix until we got to Kampala in Uganda. ‘Temporary fixes’ were seeing us through equatorial Africa as they had done when we crossed the Sahara.

The busy noise of saucepans drifted through from the kitchen followed by a harsh volley of shouts in the local dialect. Costas disappeared for ten minutes and shortly afterwards dinner was announced. Three barefoot Congolese silently laid out salad, potatoes, tomatoes, bread and feta cheese. Japheth cast a critical eye over the proceedings, and rearranged some of the dishes.

We made up a party of seven. This being our first Greek meze we didn’t understand the need to pace ourselves through the meal, so our stomachs groaned when the first course was cleared away and we were faced with steak and chips, herring, and chicken in tomato sauce.

‘And here is the Queen Mary,’ announced Costas, as an enormous platter of spaghetti was carried to the table by two of the kitchen staff and put alongside the rest of the food.

Dessert of creamed rice and cinnamon finished off both the meal and us. To top it all we toasted each other with a glass of the liqueur Marie Brizard.

The organisation and sourcing of ingredients for what we’d just eaten must have been monumental. It was likely that all the fresh vegetables were home-grown, but the rest must have been brought in by special deliveries or by the Greeks themselves. The country’s infrastructure was practically nonexistent, the roads unreliable, and only good managers could enjoy a reasonable quality of living.

Between seven of us we ate about half of this feast, and we’d hardly dented the mound of spaghetti. Blatant over-catering gave Costas the reputation of a generous host and wise old Japheth knew that the remainder would be left for him to share out between the staff and their families. It was a game that was played out all over the colonies, even after independence, in a silent agreement to let both sides win. Costas disappeared again into another room.

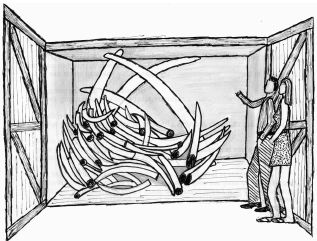

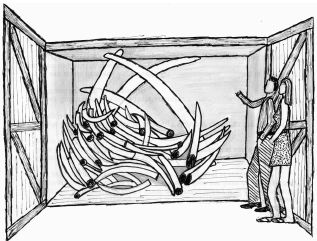

Sitting back replete after the marathon food fest the subject of war atrocities came up again. We sat out on the veranda to a shrill chorus of crickets, and moths throwing themselves against the yellow lights above our heads. During the uprising in 1964 the whites were attacked at night without warning in their homes. The rebels would burst out of the bushes with guns and dance around them. Their faces daubed with mud, and their bodies covered in leaves and feathers, to complete the picture they wore saucepans on their heads in an attempt to mimic military helmets. Their resulting comical appearance was a reality of horror. All the servants and factory workers ran into the bush when these trouble-makers arrived in town. Brutal men took what they wanted, helping themselves to food and women and generally throwing their weight around. The least show of resistance met with blows from fists and rifle butts. Dimitri showed us his deformed arm which had been repeatedly beaten with the butt of a rifle when he found himself in the way of an angry rebel. Driven out of their homes they watched helplessly from a distance for eight days as the order they had coaxed out of wilderness was trashed and vandalized. Treasured furniture shipped from Europe and painstakingly transported over miles of bush roads broke easily under hammer blows and burned with a strong flame under black cooking pots. The smell of roasting human flesh pervaded those eight gruesome evenings. Mostly it would be hapless villagers dragged out from their hiding places. Atrocities fuelled by the stash of Ouzo they had found in the Greeks’ houses were the stuff of pre-dinner entertainment and gave the perpetrators an appetite for the meat of their victims. In Aba all of the nuns and missionaries had been killed and eaten. Raw fear forced many village boys to join the rag-tag army and most were never seen again.

A loud banging of saucepans made us jump and two Congolese men with their faces painted white and their bodies covered in leaves, leapt out of the shadows at Ross and me, grabbing my arms. They had tin cans on their heads and carried bows and arrows as they danced around us.

‘What’s going on?’ I gasped, completely taken by surprise and adrenaline already pumping around my system, the pictures of torture, rape and murder fresh in my mind. Ross looked equally confused and had jumped to his feet. We both looked to our host for an explanation and saw Costas’ shoulders shaking and a hand covered his mouth. The men then all started laughing aloud at their staged joke. Costas had dressed up the staff to re-enact the rebel intrusion. We were grateful they hadn’t left us to face the scene alone and at least there were no guns involved.

Costas talked again about the violent chaos they had survived. Greek traders and businessmen kept out of politics, and they all managed to escape into the bush with minor injuries. From there some managed to flee the country, but our stalwart hosts had stayed. Not knowing how long their ordeal would last, they lay low until the rebel forces moved on to their next target. Most of their businesses and properties were ransacked or destroyed and they lost everything, as did all the European settlers. Men had started returning to get things up and running again, and it would be a while before they had any female company. Those few women and children who had come from Greece to be with them had mercifully been sent back to Europe at the first sign of trouble.

At the end of the evening Costas presented us with an ivory snail as a souvenir of the Congo. We didn’t enquire about its provenance but his generosity touched us and the next day he also pressed a kilo of coffee beans from his plantation into my hands. Another night in a comfortable bed made us feel properly pampered.

24th November

We enjoyed a light breakfast, and then I stayed in the house while Ross went to see about more car repairs. I heard raucous singing and went to the window in time to see a lorry crammed full of Congolese men and women going past, celebrating the anniversary of Mobutu’s coming to power with everyone already the worse for drink at ten o’clock in the morning.

‘We would have been sailing from Southampton to Cape Town today if we’d stuck to our original plan.’ I said to Ross when he returned.

‘Yes, but think what we would have missed!’ he replied.

In the afternoon Stavros took us to see his parents’ soap factory, ransacked by the rebels in 1964. We stepped warily over weeds which had taken over the path, looking for snakes, and followed him into a bare echoing concrete building. All of the machinery and vehicles had been taken away or destroyed. He took some photos then we headed for his old house, now inhabited by a Congolese family. At the entrance the pungent perfume of Frangipani hit us, and we spotted the surviving plant reaching up from a tangle of weeds defiantly producing fragrant waxy flowers in the chaos. A turbulent bougainvillea clambered high and wild over an adjacent Mopane tree, and the remnants of a stone wall guarded thin leggy geraniums with tiny red blooms that hinted at once carefully tended flower beds. Not a stick of furniture remained and the cold ashes of a cooking fire lay in the middle of the ‘sitting room’. A malodorous heap of accumulated rubbish and what smelt like sewage was piled up in a corner and a listless young woman sat on the floor with a rag-clad baby clinging to her breast. Stavros greeted her and she nodded and looked away. His lovely house had gone to ruin, and acknowledging his painful memories we returned in silence to Costa’s house to wait for dinner.

Still waiting for the festivities to finish we enjoyed another lazy afternoon, decadently taking showers and chatting away the hours. Stavros appeared later on and presented us with a finely carved ivory antelope as yet another souvenir of the Congo. We protested at such generosity, but he was determined to spoil us. At dusk Japhet had disappeared for the celebrations, so Andreas commissioned his own cook to prepare the next feast for us all.

Another evening of good food worked wonders on our deprived systems with dolmas, (spiced meat and rice rolled up in cabbage leaves and served with yoghurt), steak, vegetables and chips.

25th November

Having been thoroughly fed, watered and rested by our wonderful hosts, we said farewell and made an early start. They had made our memories of the Congo a good experience instead of the horror we’d expected and we couldn’t thank them enough. Fearing evil in this country we had found nothing but kindness.

The longer but less risky road took us north onto higher ground then east to Faradje. By this time midday was approaching but our bellies were still full and we didn’t waste much time looking for bread. We did manage to buy cigarettes to keep us going, and used up the last of our local currency on a badly needed pair of shorts for Ross. The roads had already improved and promised to continue to do so. With the prospect of better roads ahead in East Africa Ross decided to off-load the second sand-ladder and we deposited it in a ditch at the roadside. It wouldn’t be long before someone would claim it and put it to good use. I got back into the car by my own door at last. At Aba close to the border with Sudan we turned south once more.

Again apprehensive, we approached the customs at Aru, but as before they were efficient and very friendly with no hint of trouble at all.