War consists not only in battles, but in well-considered

movements which bring the same results.

—John C. Fremont

The soldiers who occupied Gettysburg that day were from Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell’s Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. Advancing with two other corps from Fredericksburg, Virginia, through Maryland and into Pennsylvania, the Confederate army under General Robert E. Lee was on the offensive. Confident from victory over the Union’s Army of the Potomac at Chancellorsville in May, Lee had championed the idea of a new invasion of the North. It was a bold plan to win Southern independence in a single campaign, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis was behind the initiative. Robert E. Lee was the Confederacy’s greatest military commander. Graduating second in his class at West Point in 1829, Lee went on to serve in the corps of engineers. A protégé of General Winfield Scott, Lee served with valor and distinction under Scott during the Mexican War from 1846 to 1848. By the start of the Civil War, in April 1861, Lee was still only a colonel but already his reputation accorded him great respect.

BIRTH NAME: Robert Edward Lee, General the Confedente Army

BORN: January 1807, Stratford Hall, VA

DIED: October 12, 1870, Lexington City, VA

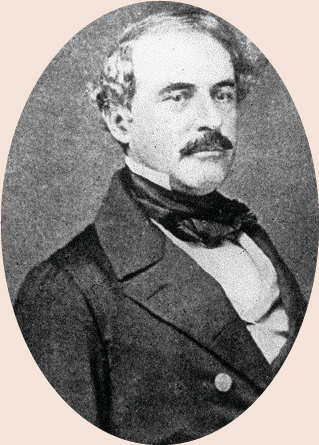

General Robert E. Lee photographed in 1862 by Julian Vannerson. Photo credit: Library of Congress; illustrated by Ron Cole.

Robert Edward Lee was born on January 19, 1807, to Revolutionary War hero and Virginia Governor Henry “Light Horse” Harry Lee III and Anne Hill Carter at Stratford Hall Plantation, Virginia. One of six children, Lee began life in difficult times, losing his father when he was only eleven years old. With the help of relatives, Anne Carter raised the children herself and saw to their education.

A promising student of mathematics at an early age, Robert secured an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point when he was seventeen. There he distinguished himself by graduating second in his class in 1829. Two years later he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis, great-granddaughter of Martha Washington. They would have seven children over the years, three boys and four girls. All three of Lee’s sons became officers in the Confederate army. Robert inherited his father’s estate in 1857, including the Arlington plantation across the Potomac from Washington, DC.

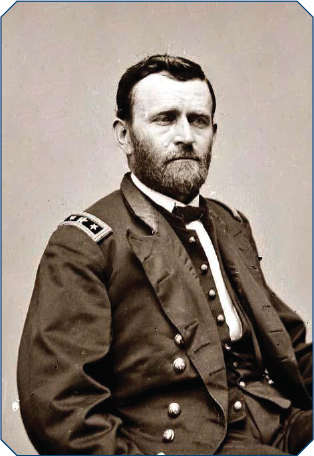

Lee served as a lieutenant of engineers at a number of civil projects until the Mexican War in 1846. That year he served as an aide to General Winfield Scott on his triumphant march from Vera Cruz to capture Mexico City. It was in this campaign that Lee earned commendation from the commanding general for his skill and courage as a scout. He also met and served with Ulysses S. Grant, to whom he would eventually surrender at Appomattox in 1865.

After the war Lee was promoted to colonel and served as the superintendent of West Point for three years. He finally received a combat command when he was assigned to the Second Cavalry regiment in Texas in 1855, where he faced off against Apache and Co-manche raiders. He later commanded the detachment that put down John Brown’s uprising at Harper’s Ferry in 1859. After Texas seceded from the Union in February 1861, Lee returned to Washington and was appointed Colonel of the First Regiment of Cavalry in March.

Of utmost importance to Lee was adherence to duty. The idea that the South would attempt to leave the Union and form a new country troubled him deeply. He wrote to his son William Fitzhugh in 1861, “I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union.” When asked by a friend if he intended to resign from the army to join the Confederacy he replied, “I shall never bear arms against the Union, but it may be necessary for me to carry a musket in the defense of my native state, Virginia.”

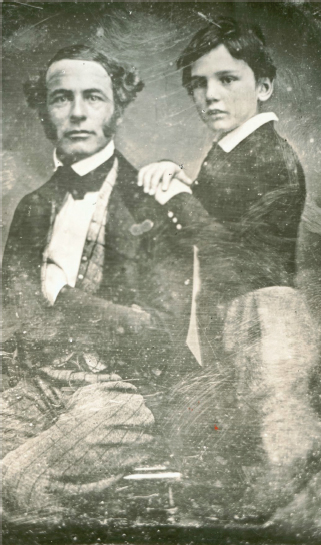

Robert E. Lee, around age forty-three, when he was a Brevet Lieutenant Colonel of Engineers, c.1850. Photo credit: Matthew Brady.

The same day the Virginia state government met to debate joining the Confederacy on April 18, 1861, Lincoln offered Lee the rank of major general and command of the Union army. Yet, Lee knew that Lincoln was raising an army of volunteers to invade the South, and that Virginia would join the Confederacy. He refused to accept command of an army that would be ordered to invade his home.

Lee resigned from the United States Army on April 20, and accepted command of the Virginia state forces three days later. He wrote to his sister, “With all my devotion to the Union, and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relative, my children, my home. I have, therefore, resigned my commission in the Army, and save in defense of my native State (with the sincere hope that my poor services may never be needed) I hope I may never be called upon to draw my sword.”

Upon the formation of the Confederate States Army, Lee was promoted to one of its five full generals. A year later, Lee was given command of the Army of Northern Virginia on June 1, 1862, during the fighting against George McClellan’s invasion of the peninsula. In the months that followed, Lee would prove more than a match for a succession of Union generals ordered south to try to capture Richmond.

An aide to Jefferson Davis once said that “Lee is audacity personified.” The Gettysburg campaign was in every way an extension of Lee’s character as a man of action. By the summer of 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia was at its strongest. Lee must have known that the tide of war would soon crush the Confederacy. He believed the attack into Pennsylvania was their best hope for winning independence while the South retained the initiative to make such a campaign.

Robert E. Lee, around age thirty-eight, and his son, William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, around age eight. Photo credit: Encyclopedia Virginia.

Lee had every faith in his men and officers. He wrote of his soldiers before Gettysburg, “There never were such men—in any army before and there never can be better in any army again. If properly led, they will go anywhere and never falter at the work before them.” Lee’s belief in his men was central to his thinking when he ordered Pickett’s Charge on July 3, at Gettysburg. His iron will could not accept the possibility of defeat on such a crucial field of battle.

When Lee surrendered to General Grant at Virginia’s Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, 1865, they both set a tone for the reconciliation between the states that followed. Lee had refused the desire of many Confederate officers to disband the army and fight a guerrilla war against the federal government. Grant, in turn, gave Lee the most generous terms of surrender possible, allowing his troops to return to their homes. Lee also welcomed the end of slavery saying, “So far from engaging in a war to perpetuate slavery, I am rejoiced that slavery is abolished. I believe it will be greatly for the interests of the South.”

Lee was revered by his soldiers more than any other American officer in history. An eyewitness to the surrender at Appomattox recorded, “When, after his interview with Grant, General Lee again appeared, a shout of welcome instinctively ran through the army. But, instantly recollecting the sad occasion that brought him before them, their shouts sank into silence, every hat was raised, and the bronzed faces of the thousands of grim warriors were bathed with tears. As he rode slowly along the lines, hundreds of his devoted veterans pressed around the noble chief, trying to take his hand, touch his person, or even lay a hand upon his horse, thus exhibiting for him their great affection.”

After the war, Lee would go on to great achievements in peace, accepting an offer to serve as the president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia. Whatever his private misgivings were about the federal government he publicly supported reconciliation with the North and signed an oath of allegiance to the United States. Lee also appealed to President Johnson for an amnesty and pardon for his role in taking up arms against the government. His pardon was not granted until 1975 by President Gerald Ford.

Lee passed away on October 12, 1870, at the age of sixty-three in Lexington, Virginia. Over the years, Lee’s memory became honored by both sides as a great general, a man of principle, and a man who, in the end, proved he was as equally great in the service of peace as in war. In 1874, Benjamin Harvey Hill described Lee as “... a foe without hate; a friend without treachery; a soldier without cruelty; a victor without oppression, and a victim without murmuring. He was a public officer without vices; a private citizen without wrong; a neighbor without reproach; a Christian without hypocrisy, and a man without guile. He was a Caesar, without his ambition; Frederick, without his tyranny; Napoleon, without his selfishness, and Washington, without his reward.”

At the request of General Scott, Lincoln approved offering Lee command of the Union Army at the start of the war, but Lee knew that the army Lincoln was forming would be ordered into the southern states to put down the current rebellion. It would require that he turn against the people of his native state of Virginia. Lee decided this was something he could not do, so he resigned his commission in the United States Army and returned home.

Writing to his sister on April 20, 1861, Lee explained: “With all my devotion to the Union, and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relative, my children, my home. I have, therefore, resigned my commission in the Army, and save in defense of my native State (with the sincere hope that my poor services may never be needed) I hope I may never be called upon to draw my sword.” Three days after writing this letter, Lee accepted command of the military forces of Virginia. Within months he was promoted to one of only five full generals in the newly formed Confederate States Army.

Lee’s first opportunity to lead an army in the field came a year later, in June 1862. Union General George McClellan had landed the massive Federal army on the Virginia peninsula and was advancing toward Richmond. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia, was wounded in the early fighting and Lee was given command. Seizing the initiative, Lee attacked in what became known as the Battle of Seven Days, forcing McClellan’s army back to the coast, where they eventually retreated to Maryland.

“General Lee is, almost without exception, the handsomest man of his age I ever saw. He is fifty-six years old, tall, broad shouldered, very well made, well set up—a thorough soldier in appearance; and his manners are most courteous and full of dignity. He is a perfect gentleman in every respect. I imagine no man has so few enemies, or is so universally esteemed. Throughout the South, all agree in pronouncing him to be as near perfection as a man can be. He has none of the small vices, such as smoking, drinking, chewing, or swearing, and his bitterest enemy never accused him of any of the greater ones. He generally wears a well worn long gray jacket, a high black felt hat, and blue trousers tucked into his Wellington boots. I never saw him carry arms.”

—Colonel Arthur James Lyon Fremantle

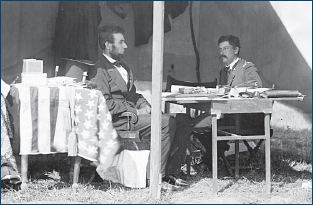

President Lincoln meets with General McClettan after the Battle of Antietam, October 3, 1862. Photo credit: Ahxander Gardner, Library of Congress.

McClellans defeat was a humiliating setback for Lincoln’s war effort and a significant victory for Lee. The troops under his command realized they had a brilliant and daring general leading them, and they began calling him “Marse Lee”—a reference of respect as master. Over the next twelve months, three decisive Confederate victories were achieved under Lee’s command: Second Manassas, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville.

Major General George B. McClellan. Photo credit: Matthew Brady.

In September 1862, Lee took his army into Maryland on his first invasion of the North. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac attacked them at Antietam in what became the bloodiest day in American history. Lee’s army fought with their backs to the Potomac River, crushing the Union assaults against their lines. Both sides suffered terrible losses, and Lee pulled his army back across the river into Virginia to safety. Lee’s daring and tactical skill saved his army from defeat, but their retreat to Virginia allowed Lincoln to claim this as a major Union victory.

Even with Lee’s impressive victories, the war approached disaster for the Confederacy by 1863. The Union had seized control of the Upper Mississippi in February 1862, took key forts in Tennessee, and won a defensive battle at Shiloh. And much further to the south, Union forces had captured New Orleans in May 1862, cutting off the Mississippi to foreign trade and depriving the Confederacy of her most vital port.

By the summer of 1863, Grant was leading a siege against the fortress city of Vicksburg in Mississippi, defended by 30,000 Confederate soldiers. If Grant were to take this major river city, the entire Mississippi river would fall under Union control, splitting the Confederacy in two. The strength of the Union army and northern industry was growing stronger while the Confederacy weakened. Every battle, victorious or not, cost the South thousands of men that could not be replaced. Time, it seemed, was running out for the South. Their only route to victory lay on the battlefield—so all eyes looked now to General Lee to deliver that victory, the one general who repeatedly crushed the Union armies sent to invade Virginia.

Major General Ulysses S. Grant. Photo credit: Matthew Brady.

... Nothing gave me much concern so long as I knew that General Lee was in command. I am sure there can never have been an army with more supreme confidence in its commander than that army had in General Lee. We looked forward to victory under him as confidently as to successive sunrises.

—Colonel Edward Porter Alexander

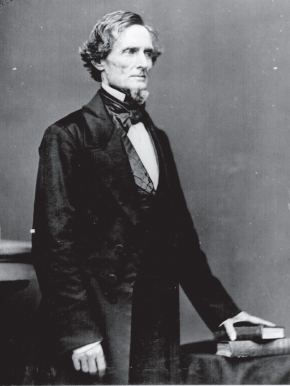

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America. Photo credit: National Archives.

Lee’s plan was to move the Army of Northern Virginia north through the Blue Mountains using Major General J. E. B. Stuart’s cavalry to screen their movements from the enemy. Once he crossed the Potomac River into Maryland, Lee would take his army into Pennsylvania, where they could “live off the enemy’s land” and capture much-needed supplies. By threatening to occupy Harrisburg, the capital of Pennsylvania, Lee hoped to draw the Army of the Potomac out of Virginia and into the open fields where it could be decisively attacked. A major victory over the Army of the Potomac would likely draw Union forces away from the southern states, win foreign recognition, and even force Lincoln to the peace table.

Lee had every confidence in his men and in his own ability to defeat the enemy. Writing after his victory at Chancellorsville, Lee noted, “There never were such men—in any army before and there never can be better in any army again. If properly led, they will go anywhere and never falter at the work before them.” An aide to President Jefferson Davis commented that “Lee is audacity personified.” Lee now staked that reputation in an all-out campaign to bring the war to an end by invading the North.

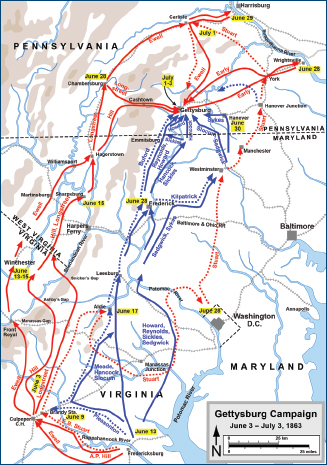

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com.

On June 3, 1863, Lee’s army slipped away from their defenses at Fredericksburg and moved northwest toward Culpeper, intending to cross the Rappahannock River and enter the Shenandoah Valley. Two days later, Major General Joseph Hooker, commanding the Army of the Potomac, received intelligence that Lee’s forces were on the move. He telegraphed a message to his superiors in Washington, proposing an attack on Lee’s defenses at Fredericksburg and then to move on to Richmond. President Lincoln immediately replied, “If Lee would come to my side of the river, I would keep on the same side, and fight him or act on the defense ... Lee’s army, and not Richmond, is your sure objective point.”

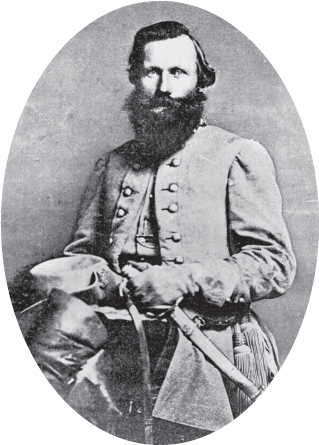

Major General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart. Photo credit: George S. Cook, National Archives.

Major General Joseph Hooker. Photo credit: Matthew Brady, Library of Congress.

During those first weeks of June, Lee’s army was protected from Union view behind a screen of cavalry commanded by Major General J. E. B. Stuart. In an effort to break through and gain information on Lee’s intentions, on June 9, General Hooker sent his own cavalry to make a surprise attack on Stuart’s camps across the Rappahan-nock River at Brandy Station. In what became one of the largest cavalry battles in U.S. history, Hooker’s effort almost succeeded. Stuart and his command were caught off guard by the dawn attack, but skillfully rallied a defense. By dusk, the Union cavalry was compelled to withdraw north of the river, thus giving the Confederates a tactical victory.

Stuart claimed a victory, but the Richmond newspapers criticized his leadership. The Richmond Enquirer wrote that “General Stuart has suffered no little in public estimation by the late enterprises of the enemy.” The Richmond Examiner described Stuart’s command as “puffed up cavalry,” that suffered the “consequences of negligence and bad management.” Stuart was considered by many as the Confederacy’s most brilliant cavalry leader and a national hero, so such harsh words cut him deeply. And this wounding of his pride would have dire consequences for the Pennsylvania campaign in the coming weeks.