On crossing the Potomac, the army appears

to be morally transformed...

—Régis de Trobriand

The Army of the Potomac began leaving their camps at Fredericksburg on June 13, marching north toward ?Ü. Frederick, Maryland, to shadow Lee’s army. Thus began a long twenty-seven-day march in blazing hot weather for two massive armies seeking battle. The morale on both sides was high as all men knew the stakes of losing this fight. George T. Stevens, a surgeon in the 77th New York Volunteers, recalled, “The men were eager, notwithstanding their comfortable quarters, for active campaigning. The health and spirits of the soldiers of the corps had never been better, and in spite of the failure at Chancellors -ville, they felt a great deal of confidence. So the order to move was received with pleasure, and we turned away from our pleasant camps willingly.”

The following day, Lee’s Second Corps, under the command of Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell, attacked the Federal garrison at Winchester, Virginia, capturing 4,000 prisoners, scores of supply wagons, horses, hundreds of rifles, and twenty-eight cannons. With the Confederate army now well supplied, the road north lay wide open for Lee’s invasion. Ewell ordered his cavalry brigade into Pennsylvania as far north as Cham-bersburg. He wanted the faster moving mounted troops ahead of his corps to help raid and capture supplies.

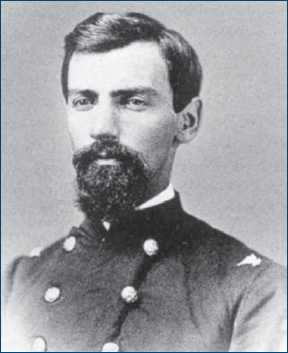

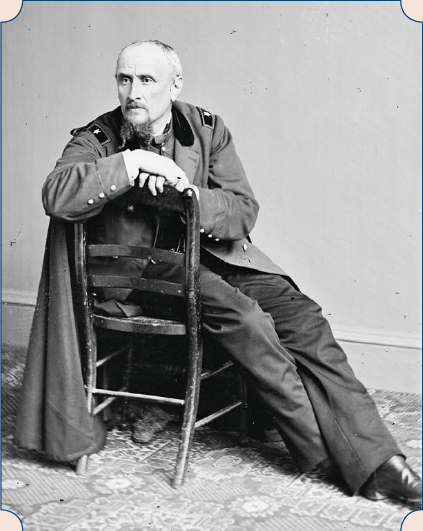

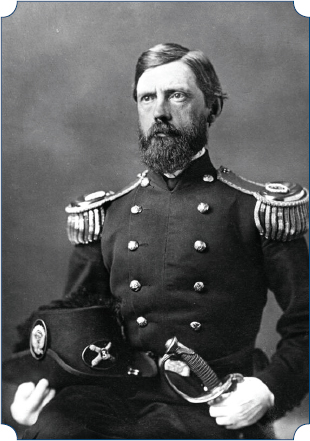

Lieutenant General Richard Stoddert Ewell. Photo credit: National Archives.

Among the fallen from the battle at Winchester was Union Corporal Johnston “Jack” Skelly, a Gettysburg native. Mortally wounded, he wrote a farewell note to his fiancée back home—Mary Virginia Wade. By a stroke of good luck he met a close friend just before he died, Private Wesley Culp, another Gettysburg resident who volunteered for the Confederacy. Wesley had gone to school with both Jack and Mary. When he came across Jack at a field hospital the wounded soldier gave him a note to pass on to Mary.

“Ewell is rather a remarkable looking old soldier, with a bald head, a prominent nose, and rather a haggard, sickly face; having so lately lost his leg above the knee, he is still a complete cripple, and falls off his horse occasionally.”

—Colonel Arthur James Lyon Fremantle

Corporal Johnston “Jack” Skelly

Mary Virginia “Ginnie” Wade

The loss at Winchester stunned the North, and Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin raised the call for 50,000 volunteers to defend the state against the Southern army’s move north. Tillie Pierce wrote about Gettysburg’s home grown militia: “I remember one evening in particular, when quite a number of them had assembled to guard the town that night against an attack from the enemy. They were ‘armed to the teeth’ with old, rusty guns and swords, pitchforks, shovels and pick-axes. Their falling into line, the maneuvers, the commands given and not heeded, would have done a veteran’s heart good.”

Private Wesley Culp

Lieutenant Colonel Rufus Dawes

The Union veterans Tillie envisioned were at the moment setting out for Maryland and then Pennsylvania to confront Lee’s army. Colonel Rufus Dawes was commander of the 6th Wisconsin, one of five regiments of the elite “Iron Brigade.” In a letter to his fiancée on June 15, he wrote: “We are to march this morning positively. I think the whole army is going, for the order is from General Hooker ... The regiment will go out strong in health and cheerful in spirit, and determined always to sustain its glorious history. It has been my ardent ambition to lead it through one campaign, and now the indications are that my opportunity has come.”

On June 15, Ewell led his Second Corps across the Potomac River near Hagerstown, Maryland. His was the first Confederate corps to enter Pennsylvania a week later on the 22nd. Over the next week they marched through Greencastle to Chambersburg, then east to Gettysburg, where Tillie Pierce saw them for the first time, and northward to York County. Ewell’s corps wanted to be in position for Lee to threaten Harrisburg, the state capital. Along the way, Ewell’s troops levied towns for supplies of all kinds—food for the troops and horses for the cavalry. They took lots of property, even though Lee had ordered that nothing was to be seized or destroyed by his men outside the direct needs of the army. The order was quietly ignored by the hungry soldiers, but for an invading army, they took no revenge against the northern civilians—no homes were burned or families harmed.

Many of those who lost property in the wake of Lee’s invasion fared better than civilians in the South, who had suffered during Federal occupation. At Fredericksburg in December 1862, undisciplined Union troops had pillaged the town. As the Army of the Potomac left Virginia to pursue Lee that summer of 1863, they left behind a countryside devastated by war.

The southerners were impressed by the Pennsylvania country through which they were marching. Summer was in full bloom with fields of waving wheat, orchards laden with ripe fruits, and quiet pastures of cattle beside the huge red barns of the Pennsylvania Dutch. Cavalryman James H. Hodam recalled, “The cherry crop was immense through this part of the state, and the great trees often overhung the highway laden with ripened fruit. The infantry would break off great branches and devour the cherries as they marched along.”

The country through which we passed towards Gettysburg seemed to abound chiefly in Dutch women who could not speak English, sweet cherries, and apple-butter. As we marched along, the women and children would stand at the front gate with large loaves of bread and a crock of apple-butter, and effectually prevent an entrance of the premises by the gray invaders. As I said before, the women could not talk much with us, but they knew how to provide” cut and smear, “as the boys called it, in abundance.

—James Hodam, 17th Virginia Cavalry

On Sunday the 28th retreating Union militia set fire to the mile-long Columbia Bridge over the Susquehanna River to prevent its capture. “The scene was magnificent,” wrote a reporter. “The moon was bright, and the blue clouds afforded the best contrast possible to the red glare of the conflagration. The light in the heavens must have been seen for many miles.” By the next morning Ewell had received new orders from Lee. He would lead his men back the way they had come, south toward Gettysburg, and link up with A. P. Hill’s and Longstreet’s forces advancing eastward from Chambersburg.

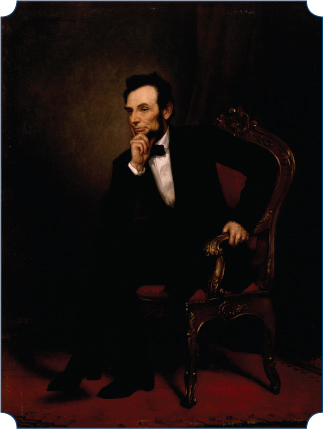

At the end of June, President Lincoln was concerned that Commanding General Hooker would lose his nerve when facing Lee a second time on the battlefield. Promoted to command after General Burnside’s disaster at Fredericks-burg in December 1862, Hooker had been quoted during the retreat by the New York Times as saying that “nothing would go right until we had a dictator and the sooner the better.” A few weeks later Lincoln promoted Hooker to command the army and wrote to him, “I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain success can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship.”

President Abraham Lincoln painted by George Peter Alexander Healy. Photo credit: White House Collection.

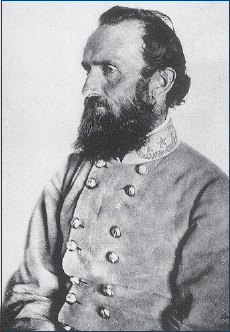

Three short months later, during the first week of May, Hooker failed to deliver that success and the Army of the Potomac had to retreat after General Lee’s crushing victory at Chancel-lorsville. It was perhaps Lee’s greatest victory, but also the costliest. Among the thousands of fallen soldiers was Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Lee’s greatest corps commander. After his death on May 10, Lee confessed in a letter to his son Custis, “It is a terrible loss. I know not how to replace him.”

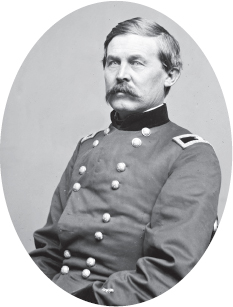

General Hooker skillfully regrouped his army and had set them in motion to follow Lee’s advance into Maryland, with five of his seven infantry corps ready to enter Pennsylvania and challenge Lee. But Lincoln could not afford to lose another battle. With his own officers questioning Hooker’s ability to lead, the General knew he had also lost the confidence of the President and, thus, resigned command on June 28. Lincoln now chose Major General George Gordon Meade to replace Hooker. Only days before the largest battle of the Civil War, the Army of the Potomac suddenly had a new commander.

Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson

BRITH NAME: George Gordon Meade, General of the Unoin Army

BRON: December 31, 1815 in Cadiz, Spain

DLED: November 6, 1872

Major General George Gordon Meade photographed by Matthew Brady. Photo credit: Library of Congress; illustrated by Ron Cole.

George Meade was born in Cadiz, Spain, the eighth child of eleven born to Richard Worsam Meade and Margaret Coats Butler. His father was from Philadelphia, and was a wealthy merchant serving in Spain as a naval agent for the United States. Financially ruined by the Napoleonic Wars, his father died when young George was not yet a teenager. The family, in danger of financial collapse, returned to the United States in 1828.

In part because West Point offered young men a free education, George entered the academy in 1831, graduating nineteenth in his class of fifty-six cadets in 1835. He served one year with the 3rd U.S. Artillery in Florida, fighting in the Seminole War before resigning his commission to begin a career as a civil engineer.

In 1840, George married Margaretta Sergeant and they had seven children who gave him seven children over the years. George returned to the army as a second lieutenant in the Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1842.

Between 1846 and 1848, Meade served in the Mexican War, for which he was promoted to first lieutenant for bravery at the Battle of Monterey. When he returned to the United States, Meade was assigned further civil projects, such as building lighthouses and breakwaters in Florida and New Jersey. He was promoted to captain in 1856. When the Civil War broke out, Meade was working on a surveying mission to the Great Lakes region.

Promoted to brigadier general of volunteers in August of 1861, Meade took command of the 2nd Brigade of the Pennsylvania Reserves and helped design the construction of defenses around Washington, DC. The brigade fought with McClellan’s army during the Battle of Seven Days at which Meade suffered wounds to his arm, back, and side. He recovered in time to fight again at Second Bull Run. At the Battle of South Mountain he was given command of the 3rd Division, First Corps and fought bravely with his troops yet again.

Meade had established himself as a “fighting general,” earning the respect of his troops and the officers above him. At the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Meade took command of the First Corps when its commander, Joseph Hooker, was wounded. Meade was wounded again, this time in the thigh, during this battle. At Fredericksburg that December, Meade’s division made the only breakthrough of the Confederate lines, attacking Lieutenant General “Stonewall” Jackson’s corps. Promoted to major general and given command of Fifth Corps, Meade would fight again at Chancellorsville in May 1863.

In the pre-dawn hours of June 28, a special messenger reached Meade, who was encamped with the army near Frederick, Maryland. In a letter from Halleck, Meade was promoted to command the Army of the Potomac, with orders to confront Lee as he invaded Pennsylvania. Unknown to Meade at the time, that confrontation was only three days away.

Meade was an inspired choice by Lincoln. He was a proven combat leader, one without political ambitions, and Lincoln knew he could count on him to defend Pennsylvania from Lee’s invasion. Where other generals had shown timidity in opposing Lee aggressively, Meade knew his duty was to seek battle.

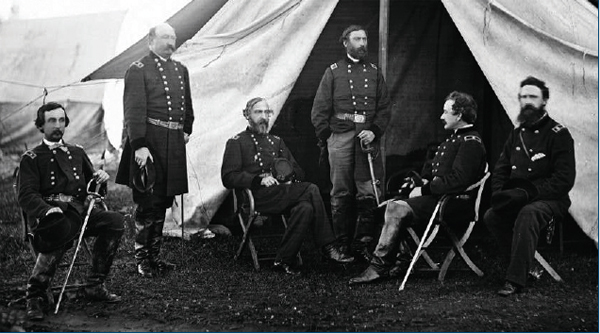

In a plain little wall-tent, just like the rest, pen in hand, seated on a camp-stool and bending over a map, is the new “General Commanding” for the army of the Potomac. Tall, slender, not ungainly, but certainly not handsome or graceful, thin-faced, with grizzled beard and moustache, a broad and high but retreating forehead, from each corner of which the slightly-curling hair recedes, as if giving premonition of baldness—apparently between forty-five and fifty years of age—altogether a man who impresses you rather as a thoughtful student than as a dashing soldier—so General Meade looks in his tent.

—Whitelaw Reid

General Meade (seated at center) with generals on his command staff at Culpeper, Virginia, in September 1863. Gouverneur K. Warren is on the left. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

On the night of June 30, he wrote his wife: “All is going on well. I think I have relieved Harrisburg and Philadelphia, and that Lee has now come to the conclusion that he must attend to other matters. I continue well, but much oppressed with a sense of responsibility and the magnitude of the great interests entrusted to me . . . Pray for me and beseech our heavenly Father to permit me to be an instrument to save my country and advance a just cause.”

The battle at Gettysburg over the next three days was the crowning moment for Meade in a lifetime devoted to the service of his country. As a topographic engineer, Meade knew the importance of holding the key terrain on any battlefield. In the early hours of the fighting, Meade entrusted his best officers to lead in his stead and to make decisions that could win or lose the battle before he was even on the field. In this he was most ably served by Buford, Reynolds, and Hancock, who collectively saved the heights near Gettysburg from falling into Lee’s hands.

Meade’s great success on July 3, in defeating Pickett’s Charge was quickly followed a few weeks later by what many considered his greatest failure. With the Potomac River flooded by heavy rain and his only pontoon bridge captured by Union cavalry, Lee was trapped on the northern bank, dug in behind fixed positions in front of Williamsport. Meade was cautious, though, and this time to a fault.

The caution and thoroughness he displayed at Gettysburg worked against him, faced off with Lee now on the defensive. Just miles away was Antietam where a year earlier, under very similar circumstances, Lee had fought tenaciously against a Union attack that became the single costliest day of fighting in American history. Surely this was on Meade’s mind as he contemplated attacking at Williamsport.

With his most aggressive and able corps commander, Winfield Scott Hancock, wounded at Gettysburg, his remaining officers voted against attacking Lee at a council of war on the evening of July 12. Meade agreed to wait one more day until he had a proper reconnaissance of Lee’s position. That same evening, Lee’s engineers improvised a pontoon bridge and his army escaped over the Potomac. The old fox had slipped the noose.

Lincoln was anguished by the news. The president was quoted as saying, “We had them within our grasp. We had only to stretch forth our hands and they were ours. And nothing I could say or do could make the Army move.”

Meade promptly and furiously offered his resignation from command. This gesture Lincoln quickly (and wisely) refused, instead offering his thanks for what was accomplished at Gettysburg. Meade’s failure to prevent Lee’s escape has been a point of debate ever since. Meade retained command of the Army of the Potomac and served under Ulysses S. Grant for the remainder of the war.

Meade continued in military and public service after the war as a commissioner of Fair-mount Park in Philadelphia from 1866 until his death in 1872. The lighthouses he designed still stand as monuments to the life of peace he wished to pursue as a civil engineer.

Meade should be remembered as one of the great Civil War generals. He was one of the few combat leaders who appreciated changes in technology and tactics that made frontal assaults a tragic waste of human lives. The greatest compliment to Meade’s abilities as an army commander came from Robert E. Lee. On the night of June 28, 1863, when Lee received word that Meade had been promoted to command the Union army, he told his fellow officers, “General Meade will commit no blunder in my front, and if I make one he will make haste to take advantage of it.”

At Gettysburg, when the country needed a careful and thoughtful leader, Meade was there. His trust in his subordinates, his careful movement and deployment of vast numbers of men, guns, and supplies to Gettysburg, and his foresight in sensing Lee would attack his center line on July 3, were all marks of a great general. He was one of the few Union generals to face Robert E. Lee in open battle and to defeat him.

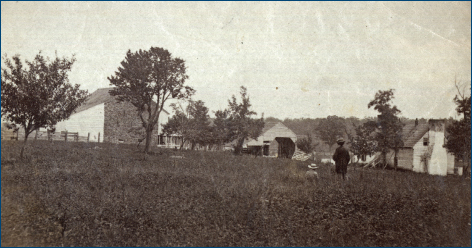

Gettysburg in 1863 taken from the Chambersburg Pike. Photo credit: Matthew Brady, Library of Congress.

On June 26, one day before crossing into Pennsylvania, General Lee told another officer, “We have again out-maneuvered the enemy, who even now don’t know where we are or what are our designs. Our whole army will be in Pennsylvania the day after tomorrow leaving the enemy far behind, and obliged to follow us by forced marches. I hope with those advantages to accomplish some signal result, and to end the war if Providence favors us.” A great battle awaited them somewhere north of the Shenandoah Valley, he said, pointing on the map in the vicinity of Gettysburg.

A few days earlier, on June 22, Lee had finalized his plan of advance with cavalry leader General Stuart. He ordered Stuart to use part of his five brigades to guard the mountain passes behind Lee’s army and lead a second force to protect the right flank of Ewell’s Second Corps as he led the way into Pennsylvania. Lee also approved a raid to circle Hooker’s army eastward if Stuart found no resistance to his movements. When Stuart set out on his mission on June 25 he encountered large units of Hooker’s army on the march. Surely, these enemy units blocking his path counted as resistance according the Lee’s orders.

“He is commonly called Jeb Stuart, on account of his initials; he is a good-looking, jovial character, exactly like his photographs. He is a good and gallant soldier...”

—Colonel Arthur James Lyon Fremantle

Stuart then made a fateful decision—he would reach Ewell’s corps by making a wide circle around Hooker’s army, going on a weeklong raid arcing through Rockville, Maryland, and on to Pennsylvania. Prideful of his near defeat at Brandy Station, Stuart felt compelled to seek glory and restore his reputation.

Nineteenth-century armies relied on the cavalry to serve as their eyes and ears—a general’s best means of tracking enemy movements and scouting terrain were via his cavalry. By taking his mounted troopers on a glorious encirclement of the Union army, Stuart broke contact with Lee’s headquarters. And in doing so, Stuart directly disobeyed Lee’s instructions and put the commanding general in the dark on the movements of the enemy during the critical days between June 25 and July 2. Lee was therefore unaware that Hooker’s army was crossing the Potomac River at Edward’s Ferry in pursuit of his forces. As Lee’s divided army moved into Pennsylvania, he moved blindly, not knowing the whereabouts of his foe or the nature of the terrain in front of him.

The Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg in 1863. Photo credit: Matthew Brady, Library of Congress.

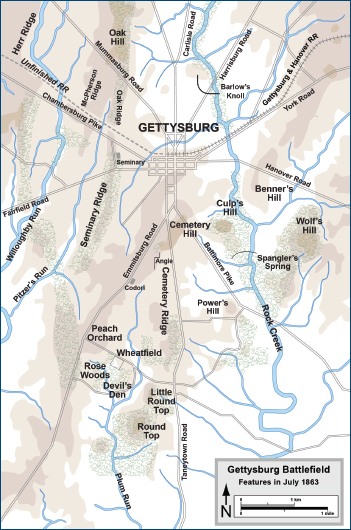

Gettysburg lies only ten miles from the Maryland border and is the seat of Adams County. In 1863, the road networks around Gettysburg were extensive. Ten major roads branched out from the town like the spokes of a wagon wheel in all directions. Anyone traveling in this part of the state would have a hard time not passing through the bustling town. Gettysburg was prosperous, with a population of about 2,400 residents. It was surrounded by rich farm country and was the home of two schools of higher learning: Gettysburg College and the Lutheran Theological Seminary. The town itself was laid out in neat rows of streets filled with brick and stone houses, stores, workshops, churches, and a small railway station. The chief industry of the time was carriage making.

Daniel Skelly in 1863, age eighteen. Photo credit: Gettysburg National Military Park.

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com.

Daniel Skelly was an eighteen-year-old employee of the Fahnestock Brothers dry goods (clothing and supplies) company in Gettysburg. He wrote of those days, “The month of June, 1863, was an exciting one for the people of Gettysburg and vicinity. Rumors of the invasion of Pennsylvania by the Confederate army were rife and toward the latter part of the month there was the daily sight of people from along the border of Maryland passing through the town with horses and cattle, to places of safety. Most of the merchants of the town shipped their goods to Philadelphia for safety as was their habit all through the war upon rumors of the Confederates crossing the Potomac.”

Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill, Jr. Photo credit: National Archives.

Lieutenant General James Longştreet

“General Longstreet is an Alabamian—a thickset, determined-looking man, forty-three years of age. He was an infantry Major in the old army, and now commands the 1st corps d’armee. He is never far from General Lee, who relies very much upon his judgment. By the soldiers he is invariably spoken of as ‘the best fighter in the whole army.’”

—Colonel Arthur James Lyon Fremantle

“Dixie”

I wish I was in the land of cotton,

Old times they are not forgotten;

Look away! Look away! Look away! Dixie Land.

In Dixie Land where I was born,

Early on one frosty mornin,

Look away! Look away! Look away! Dixie Land.

Those rumors proved all too true. Confederate Lieutenant Generals A. P. Hill and James Longstreet began moving their troops across the Potomac on June 24. On the far bank, the men were allowed to build fires and rest. Each man was given a shot of good whiskey to bolster him against the cold rain. General Lee crossed the river in a rain shower as a band hailed their commander with the tune “Dixie.” Lee was met on the Maryland shore by a delegation of ladies who welcomed him as a savior and presenting a huge wreath for his horse, Traveller.

By nightfall on the 26th, Lee’s army was camped south of Greencastle, Pennsylvania. As they entered the town the following morning, the fife and drum of the 48th Alabama Regiment played “The Bonnie Blue Flag.” The British observer Colonel Arthur Fremantle described his arrival with troops from Major General John Bell Hood’s division:

This is a town of some size and importance. All its houses were shut up; but the natives were in the streets, or at the upper windows, looking in a scowling and bewildered manner at the Confederate troops, who were marching gaily past to the tune of “Dixie Land.” The women (many of whom were pretty and well dressed) were particularly sour and disagreeable in their remarks. I heard one of them say, “Look at Pharaoh’s army going to the Red Sea.” Others were pointing and laughing at Hood’s ragged Jacks, who were passing at the time.

This division, well known for its fighting qualities, is composed of Texans, Alabamians, and Arkansans, and they certainly are a queer lot to look at. They carry less than any other troops; many of them have only got an old piece of carpet or rug as baggage; many have discarded their shoes in the mud; all are ragged and dirty, but full of good humor and confidence in themselves and in their general, Hood. They answered the numerous taunts of the Chambersburg ladies with cheers and laughter.

The Confederate soldiers were certainly in good spirits. The fruits of their invasion literally fell into their hands as captured provisions were plentiful. The men often joked that C.S.A. (Confederate States of America) actually meant corn, salt, and apples, which were the standard issues of their rations. Edward Alexander Moore, an artillerist in Longstreet’s corps, wrote of their sudden change in diet: “I give the bill-of-fare of a breakfast my mess enjoyed while on this road: Real coffee and sugar, light bread, biscuits with lard in them, butter, apple-butter, a fine dish of fried chicken, and a quarter roast lamb!”

Longstreet’s men encamped just outside Chambersburg alongside Hill’s troops. Lee arrived the following day, Sunday, June 28, and established headquarters in a quite grove called Messersmith’s Woods. Lieutenant William Owen, an artillery officer in Longstreet’s command, described the scene: “The general has little of the pomp and circumstance of war about his person. A Confederate flag marks the whereabouts of his headquarters, which are here in a little enclosure of some couple of acres of timber. There are about half a dozen tents and as many baggage wagons and ambulances . . . Lee was evidently annoyed at the absence of Stuart and the cavalry, and asked several officers, myself among the number, if we knew anything of the whereabouts of Stuart. The eyes and ears of the army are evidently missing and are greatly needed by the commander.”

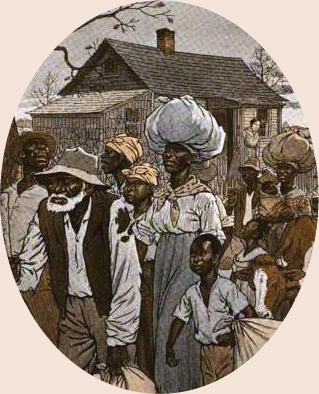

African American refugees fleeing north away from. Lee’s invasion. Illustrated by Rodney Thomson.

For the African American residents of Gettysburg, rumors of Lee’s invasion were terrifying. If captured by the rebels they would likely be put in chains and returned to slavery. Elizabeth Salome “Sallie” Myers, a Gettysburg schoolteacher, wrote of their terrible plight: “Every report of raiding would set the Africans to migrating, they were so afraid they’d be carried off into slavery. They looked very ragged and forlorn, and some exaggerated their ills by pretending to be lame, for they wanted to appear as undesirable as possible to any beholder who might be tempted to take away their freedom.”

A bank clerk from town remembered that “a great many refugees passed through Gettysburg going northward. Some would have a spring wagon and a horse, but usually they were on foot, burdened with bundles containing a couple of quilts, some clothing, and a few cooking utensils.... The farmers along the roads sheltered them nights. Most of these here poor runaways would drift into the towns and find employment, and there they’d make their future homes.”

What these refugees lacked in material possessions they made up for with hope—hope for a future free of slavery. They dreamed of a place where their children would be educated and make a life for themselves; of controlling their own destinies. By 1863, Lincoln desired to provide that very future for them by ending slavery in America forever.

At the time of the start of the Civil War, over three million African Americans remained in chains in the South. Another million slaves lived in the border states that were still loyal to the Union. However, the war that began in 1861 was not fought to end slavery. The Confederate States of America were formed, in fact, to gain southern independence in reaction to an overpowering domination by northern political interests. Lincoln’s sole purpose at the war’s start was, as he wrote in a letter to Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune in August 1862, “to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery.” Lincoln felt he had no constitutional authority to deprive citizens of their property, including slaves, even in a war of rebellion.

But as the conflict dragged into its second year with no end in sight, Lincoln’s opinion began to shift. He saw an opportunity, using the authority as Commander in Chief, to free the slaves of those states in rebellion; this would be a way to help win the war. On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued a proclamation that he would order the emancipation of all slaves in any state of the Confederacy that did not return to Union control by January 1, 1863. He also began pushing for the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery on American soil.

First reading of the “Emancipation Proclamation” of President Lincoln painted by Francis Bicknell Carpenter. Photo credit: White House Collection.

The Emancipation Proclamation redefined the war by making the abolition of slavery a primary goal for the Union. General de Trobriand summarized the effect: “It was no longer a question of the Union as it was, that was to be re-established, but the Union as it should be. That is to say, washed clean from its original sin. We were no longer merely the soldiers of a political controversy, we were now missionaries on a great work of redemption, the armed liberators of millions. The war was ennobled. The object was higher.” As Lee advanced into Pennsylvania, the Army of the Potomac knew it could not suffer another defeat; it had to win.

Brigadier General James Régis de Trobriand. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

That night a mysterious stranger was brought to Longstreet’s chief of staff, Lieutenant Colonel Moxley Sorrel: “At night I was roused by a detail of the provost guard bringing up a suspicious prisoner. I knew him instantly; it was Harrison, the scout, filthy and ragged ... He had come to ‘Report to the General, who was sure to be with the army,’ and truly his report was long and valuable.” The Federal army had crossed the Potomac three days ago and was far into Maryland. Harrison knew the locations of five of the enemy’s seven army corps. Three were already at Frederick with two more marching north from Frederick toward South Mountain. He also brought news that General Meade had taken command of the army. This information was already twenty-four hours old.

Lee had not heard from Stuart for three days now. Stuart had never before failed him. But even now Lee was unaware of Stuart’s location, and he had only the word of a paid spy on which to plan his next move. The time for action had come, though, and Lee did not hesitate. Sorrel noted, “It was on this, the report of a single scout, in the absence of cavalry, that the army moved .. . [Lee] sent orders to bring Ewell immediately back from the North about Harris-burg, and join his left. Then he started A. P. Hill off at sunrise for Gettysburg, followed by Longstreet. The enemy was there, and there our General would strike him.”

Brigadier General John Buford. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

As Meade took command on June 28, intelligence on Lee’s army became clearer. Spies in Hagerstown, Maryland, estimated the enemy’s strength at 80,000 men and 275 cannons. Meade knew Lee had sent Ewell’s corps north to York and Carlisle while Longstreet’s and Hill’s troops remained in the vicinity of Cham-bersburg. Orders were given to keep the Federal army marching northwest from Frederick to Taneytown, where Meade set up his headquarters. To screen the advance of the army, Brigadier General John Buford was ordered to take two brigades of cavalry into Gettysburg and defend the town if attacked.

Lee began moving his army east toward Gettysburg on Monday the 29th, with Hill’s Third Corps camping in Cashtown for the night. Longstreet’s First Corps would follow on the 30th as far as Greenwoood, and Ewell’s Second Corps would march south from Carlisle. Major General Henry Heth, commanding the lead division of Hill’s corps, ordered a brigade to Gettysburg on the 30th to find supplies, especially shoes, for his ill-equipped soldiers.

“Battle Cry of Freedom”

Yes we’ll rally round the flag, boys, we’ll rally once again,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom,

We will rally from the hillside, we’ll gather from the plain,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

(Chorus)

The Union forever! Hurrah, boys, hurrah!

Down with the traitor, up with the star;

While we rally round the flag, boys, rally once again,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

We are springing to the call of our brothers gone before,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

And we’ll fill our vacant ranks with a million freemen more,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

(Chorus)

We will welcome to our numbers the loyal, true and brave,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

And although they may be poor, not a man shall be a slave,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!]

Thus, by Tuesday, June 30, the Union and Confederate armies were on a collision course toward Gettysburg. Meade had only been in command of his army for two days; his troops were stretched out along the roads from Frederick—hot and exhausted from hard marching. He was about to face the legendary Robert E. Lee in what could be the decisive battle of the war. Yet Meade did have one precious advantage over Lee—he knew where his enemy was, while Lee, without cavalry, was advancing blindly.

Daniel Skelly recalled the growing tension among the people of Gettysburg: “The 28th and 29th were exciting days in Gettysburg for we knew the Confederate army, or a part of it at least, was within a few miles of our town and at night we could see from the house-tops the campfires in the mountains eight miles west of us. We expected it to march into our town at any moment and we had no information as to the whereabouts of the Army of the Potomac.”

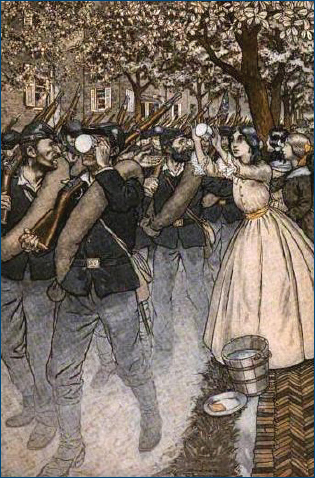

Tillie Pierce witnessed the arrival of the first Union soldiers at Gettysburg on Tuesday, June 30:

A great number of Union cavalry began to arrive in the town. They passed northwardly along Washington Street, turned toward the west on reaching Chambersburg Street, and passed out in the direction of the Theological Seminary.

It was to me a novel and grand sight. I had never seen so many soldiers at one time. They were Union soldiers and that was enough for me, for I then knew we had protection, and I felt they were our dearest friends. I afterwards learned that these men were Buford’s cavalry, numbering about six thousand men.

A crowd of “us girls” were standing on the corner of Washington and High Streets as these soldiers passed by. Desiring to encourage them, who, as we were told, would before long be in battle, my sister started to sing the old war song “Our Union Forever.” As some of us did not know the whole of the piece we kept repeating the chorus.

A little less than Tillie’s estimate, Buford had just under 3,000 men in his command and a battery of six cannon. Daniel Skelly also watched on Chambersburg Street as thousands of cavalry rode through town and thought, “Surely now we were safe and the Confederate army would never reach Gettysburg ... General Buford sat on his horse in the street in front of me, entirely alone, facing to the west in profound thought... It was the only time I ever saw the general and his calm demeanor and soldierly appearance ... made a deep imnression on me.”

Washington Street, Gettysburg, in 1863. Photo credit: Ken Gloriando.

General Buford was a West Point graduate and a veteran of the early fighting against the Sioux Indians in Texas. In 1862, Buford had fought at Second Bull Run and Antietam. At Brandy Station he commanded a division of cavalry against Stuart’s troopers. His experience was about to prove invaluable over the next three days. As he moved his troopers into the open fields north of Gettysburg they encountered Confederate soldiers in Brigadier General James Pettigrew’s brigade sent to Gettysburg for supplies. Under strict orders not to bring on a fight, the rebels fell back to Cashtown and reported their discovery of Union cavalry occupying Gettysburg.

Buford sent scouts in all directions to locate and identify what enemy units were in front of him. He knew what was at stake. A half mile behind them, just outside the town, was a low ridgeline called Cemetery Hill. At each end of that ridge were larger hills: Culp’s Hill to the north and two hills at the southern end named Little and Big Round Top. It was well known that in any battle, whoever controlled the high ground possessed a great advantage over an attacking force. Buford knew he had to delay Lee’s army long enough for the Union infantry to reinforce him and protect those heights, so he deployed his men in a series of two defensive lines centered along a wooded hill north of Gettysburg named McPherson’s Ridge.

Water for the marching troops. Illustrated by Rodney Thomson.

At 10:30 PM he sent a message to Major General John F. Reynolds, who commanded three of the infantry corps that were approaching Gettysburg from the east. He reported that Hill’s entire corps was at Cashtown, nine miles away to the west. Enemy pickets were in sight of his own along the Chambersburg Pike. Longstreet’s corps was behind Hill’s, perhaps by a day’s march.

It was a gala day. The people were out in force, and in their Sunday attire to welcome the troopers in blue. The church bells rang out a joyous peal, and dense masses of beaming faces filled the streets, as the narrow column of fours threaded its way through their midst. Lines of men stood on either side, with pails of water or apple-butter, and passed a “sandwich” to each soldier as he passed. At intervals of a few feet, were bevies of women and girls, who handed up bouquets and wreaths of flowers. By the time the center of the town was reached, every man had a bunch of flowers in his hand, or a wreath around his neck... The people were overjoyed, and received us with an enthusiasm and a hospitality born of full hearts.

—Colonel J. H. Kidd, 6th Michigan Cavalry

A captured enemy courier told him that Ewell’s corps was advancing toward Gettysburg from Carlisle from the north.

Buford knew that by morning he would face an entire rebel corps of 25,000 men. By all accounts, Buford saw that Lee was concentrating his whole army at Gettysburg. If Ewell’s corps made it to the town by the next day, two thirds of Lee’s army—50,000 soldiers—would advance against whatever Union forces could reach Gettysburg in time. When one of his brigade commanders spoke confidently of whipping any rebels the next day, Buford said, “No, you won’t. They will attack you in the morning; and they will come ‘booming’—skirmishers three deep. You will have to fight like the devil to hold your own until supports arrive.”

Major General John Fulton Reynolds. Photo credit: Reynolds family papers, Franklin & Marshall College.

The McPherson Farm photographed just after the battle in 1863. Photo credit: Matthew Brady, Library of Congress.

Reading Buford’s report Meade sent orders for Reynolds to advance his First Corps to Gettysburg in the morning with the Eleventh and Third Corps to follow. Reynolds was given command authority to act in Meade’s stead on the battlefield should there be action the next day. Meade would remain at Taneytown—fourteen miles from Gettysburg—to stay at the center of his army as events developed. Meade’s objective, in sending Reynolds to Gettysburg, was to force Lee into attacking his army on ground of his own choosing.

At Cashtown, Hill listened with disbelief that his troops had encountered Federal cavalry at Gettysburg. Brigadier General James Pettigrew insisted they had tangled with Union troopers before withdrawing. Hill believed his subordinate officer had only encountered local militia, as he had just been informed by Lee that the closest Union troops were near Middleburg, Maryland, several days away. General Heth asked his corps commander if he had any objections to advancing his division to Gettysburg in the morning. Hill replied, “None in the world.”

Major General Henry Heth

“All is going on well. I think I have relieved Harrisburg and Philadelphia, and that Lee has now come to the conclusion that he must attend to other matters. I continue well, but much oppressed with a sense of responsibility and the magnitude of the great interests entrusted to me ... Pray for me and beseech our heavenly Father to permit me to be an instrument to save my country and advance a just cause.”

—George Gordon Meade