Gettysburg was the price the South paid for

having Robert E. Lee as commander.

—Shelby Foote

Tillie was so tired from her work the night before that she didn’t wake up until late in the morning:

The first thought that came into my mind, was my promise of the night before.

I hastened down to the little basement room, and as I entered, the soldier lay there—dead. His faithful attendant was still at his side.

I had kept my promise, but he was not there to greet me. I hope he greeted nearer and dearer faces than that of the unknown little girl on the battlefield of Gettysburg.

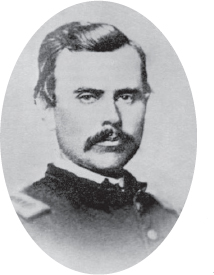

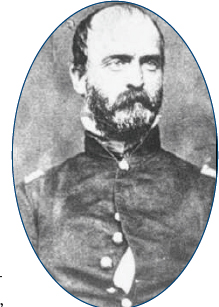

Brigadier General Stephen Hinsdale Weed

As I stood there gazing in sadness at the prostrate form, the attendant looked up to me and asked: “Do you know who this is?” I replied: “No sir.” He said: “This is the body of General Weed; a New York man. ”

At 4:30 AM, just before dawn, Lee rode over to meet with Longstreet at his field headquarters. Longstreet appealed to Lee that his scouts had found a route to outflank the Union army, but the commanding general intended to go on with the attack. Longstreet later wrote:

I was disappointed when he came to me on the morning of the 3d and directed that I should renew the attack against Cemetery Hill, probably the strongest point of the Federal line. For that purpose he had already ordered up Pickett’s division, which had been left at Cham-bersburg to guard our supply trains. In the meantime the Federals had placed batteries on Round Top, in position to make a raking fire against troops attacking the Federal front... I stated to General Lee that I had been examining the ground over to the right, and was much inclined to think the best thing was to move to the Federal left.

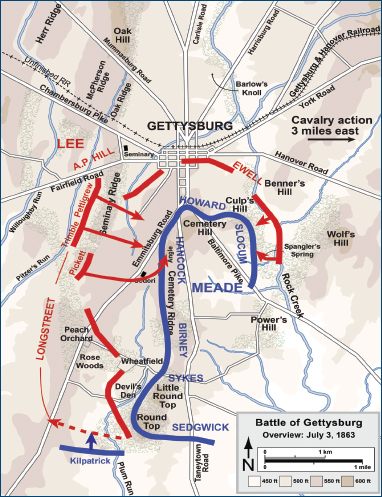

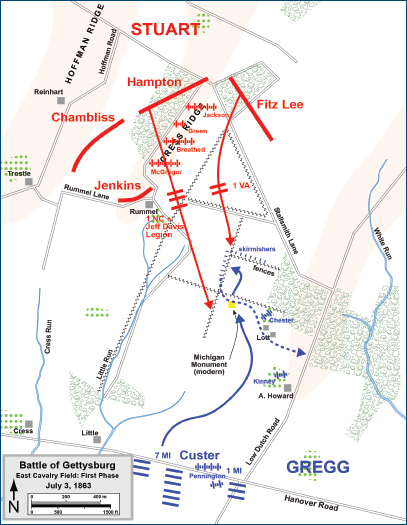

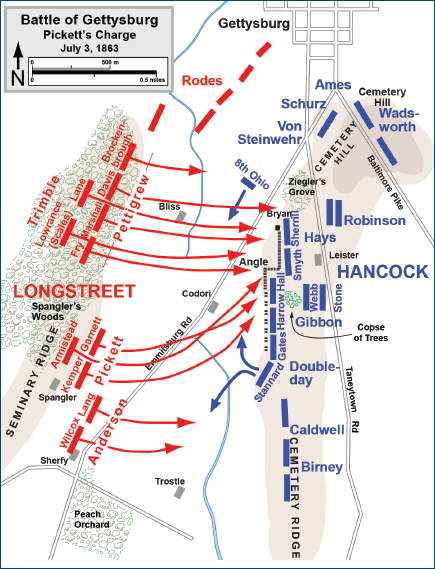

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com.

“No,” he said; “I am going to take them where they are on Cemetery Hill, I want you to take Pickett’s division and make the attack. I will reinforce you by two divisions of the Third Corps. ”

“That will give me fifteen thousand men,” I replied. “I have been a soldier, I may say, from the ranks up to the position I now hold. I have been in pretty much all kinds of skirmishes, from those of two or three soldiers up to those of an army corps, and I think I can safely say there never was a body of fifteen thousand men who could make that attack successfully. ”

The general seemed a little impatient at my remarks, so I said nothing more. As he showed no indication of changing his plan, I went to work at once to arrange my troops for the attack.

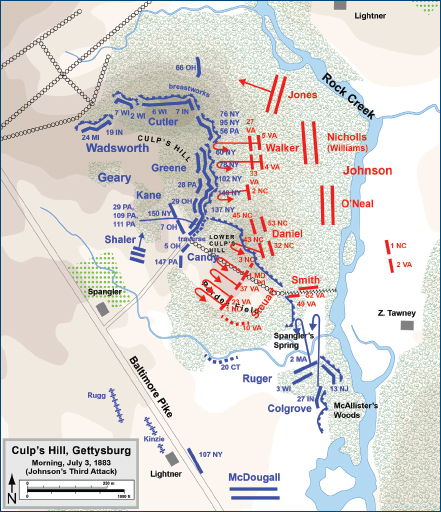

Band of Brothers—July 2, 1863. The brave men of the 1st Maryland emerge from the woodline into a wall of musketry on Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg. Illustrated by Don Troiani.

As ordered, Ewell sent Johnson’s division forward against Culp’s Hill at first light. When Lee realized Longstreet’s attack would not be ready for some time, he sent a message to Ewell to call off the attack. Ewell sent a quick reply: “Too late to recall.” The result was three more fruitless and costly assaults against Culp’s Hill, now heavily reinforced and in broad daylight, uphill, against a well-entrenched Union line. The slaughter was frightful. The two days of fighting at Culp’s Hill cost Johnson 2,000 casualties, a third of his division, and another 800 from reinforcing brigades.

To complete the tragedy, the Confederate assault on July 3, resulted in two units of Marylanders facing off against each other. The 1st Maryland Battalion Infantry of Brigadier General George H. Steuart’s Brigade in the Confederate Army attacked within thirty yards of the Union’s 1st Maryland Potomac Home Brigade. Recruited from the same counties in Maryland, former friends, neighbors, and kin now took aim at each other as the Confederates were ordered to charge the Union positions.

Major William Goldsborough, who commanded the Confederate 1st Maryland Battalion Infantry, described the fight:

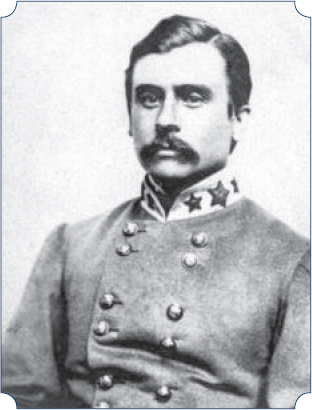

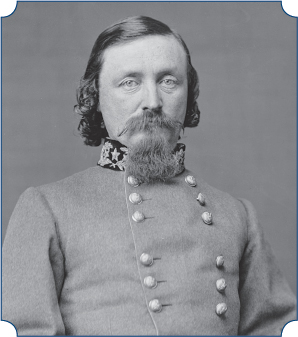

Brigadier General George Hume Steuart

A more terrible fire men were never subjected to, and it was a miracle that any escaped... But the little battalion of Marylanders, now reduced to about 300 men, never wavered nor hesitated, but kept on, closing up its ranks as great gaps were torn through them by the merciless fire of the enemy in front and flank, and many of the brave fellows never stopped until they had passed through the enemy’s first line or had fallen dead or wounded as they reached it.

But flesh and blood could not withstand that circle of fire, and the survivors fell back to the line of log breastworks, where they remained several hours, repulsing repeated assaults of the enemy, until ordered by General Johnson to fall back to Rock Creek.

General Steuart was heartbroken at the disaster, and wringing his hands, great tears stealing down his bronzed and weather-beaten cheeks, he was heard repeatedly to exclaim: “My poor boys! My poor boys!”

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com.

Colonel James Wallace of the Union’s 1st Maryland wrote, “The 1st Maryland Confederate Regiment met us and were cut to pieces. We sorrowfully gathered up many of our old friends and acquaintances and had them carefully and tenderly cared for.”

Among the fallen was John Wesley Culp of the 2nd Virginia Infantry. Originally from Gettysburg, he had moved to Shepherdstown, Virginia, in 1858. Ironically, he was killed on his uncle’s property. With Culp’s demise passed the only knowledge of the last words in a note meant for another native of Gettysburg: Mary Virginia Wade. The final words were from her fiancé, Johnston “Jack” Skelly (brother of Daniel Skelly), fatally wounded at the Second Battle of Winchester, Virginia, less than a month earlier. Tragically, none of the three was ever to know the fate of the other two.

Mary Virginia Wade, nicknamed “Ginnie” by her family and friends, was a twenty-year-old seamstress who lived with her mother and younger brother in Gettysburg. On the morning of July 1, as the battle neared town, the Wades fled to the nearby home of Ginnie’s sister, Georgia Mc-Clellan, and her newborn son on Baltimore Street. Ginnie spent most of the day distributing bread to Union soldiers and filling their canteens with water. She was determined to do everything she could for the men.

Mary Virginia Wade

After the Union Army had retreated to Cemetery Hill, her sister’s house lay between the armies. Confederate sharpshooters were firing at targets near the house, sometimes killing or wounding men in the yard or the nearby vacant lot. The cries of these wounded men made sleep impossible that night, and Ginnie risked her life to take water to these fallen soldiers. The women spent the next day handing out bread and water to any Union men who came knocking asking for food.

Early on the morning of July 3, Ginnie awoke early to bake more bread for the men. The day before, she and her mother had made yeast that they left in the kitchen to rise overnight. As Ginnie went about kneading the dough, the house came under fire from Confederate sharpshooters. Seeing movement in the house that the Confederates may have assumed to be Union soldiers taking cover in the kitchen, they opened fire. A bullet penetrated the outer door of the north side of the house, and a second door between the parlor and the kitchen, and hit Ginnie in the back under her shoulder blade. The bullet pierced her heart and killed her instantly.

Hearing the cries of Ginnie’s mother and sister, Union soldiers came and helped wrap the young woman’s body in a blanket and carried her to the basement. Ginnie’s mother, assisted by the soldiers, later returned to the kitchen— now stained by her daughter’s blood. Together they finished baking fifteen loaves of bread, all of which were given to the hungry men.

Ginnie Wade was the only civilian killed during the fighting at Gettysburg, and was hailed in the weeks to come as a national hero. Her name was misreported in the newspapers as Jennie Wade, and that is how history came to remember her.

Lieutenant Haskell saw Meade ride along Cemetery Ridge the morning of July 3, commenting that the general “rode along the whole line, looking to it himself, and with glass in hand sweeping the woods and fields in the direction of the enemy ... He was well pleased with the left of the line today, it was so strong with good troops. He had no apprehension for the right where the fight now was going on.” If Lee did try to assault his center, Meade had two of his veteran divisions of Hancock’s Second Corps defending Cemetery Ridge.

As the fighting on Culp’s Hill ceased a strange quiet fell over the battlefield. The heat of the day lulled many to sleep, exhausted at their posts. Haskell recounted, “Eleven o’clock came. The noise of battle has ceased upon the right; not a sound of a gun or musket can be heard on all the field; the sky is bright, with only the white fleecy clouds floating over from the West. The July sun streams down its fire upon the bright iron of the muskets in stacks upon the crest, and the dazzling brass of the Napoleons. The army lolls and longs for the shade, of which some get a hand’s breadth, from a shelter tent stuck upon a ramrod. The silence and sultriness of a July noon are supreme.”

Colonel Edward Porter Alexander.

Photo credit: The Photographic History

of The Civil War in Ten Volumes.

Yet across the way on Seminary Ridge, Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s corps artillery chief, was deploying over 163 cannons in a line over two miles long to bombard the Union center. Lee planned to make a concentrated strike against the Federal batteries along Cemetery Ridge to clear the way for a massive infantry assault of three divisions commanded by Trimble, Pettigrew, and Pickett. The j nine infantry brigades would have to advance over a mile of open farmland and cross the Emmitsburg Road to assault the Union line. Pickett, a favorite of Longstreet’s, would command the attack, and thus the ensuing battle would be forever remembered as Pickett’s Charge.

Major General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble

Behind the guns, hidden from view in the trees along Seminary Ridge, Lee’s infantry assembled in their brigades, preparing to attack. The ranks of men lay down with flags lowered, instructed not to cheer as officers passed. Most knew they were about to take part in a desperate undertaking that many would not survive. These men and their officers were Lee’s finest, hailing from all parts of the Confederacy. Few, if any, of these men owned slaves and they were not fighting for slavery. They had volunteered to protect their homeland and their families. They believed in Lee, who had brought them here and ordered them to make this attack. If they succeeded, they knew the war could be over by sundown.

Many have wondered why Lee planned such a desperate attack. He knew by now that he was facing all seven of the Army of the Potomac’s infantry corps. There could be no element of surprise in this assault—and the enemy now held the high ground and the stone wall from which they could rain down a devastating fire. Yet Lee was a bold and aggressive commander. The fate of the Confederacy lay in his hands. This opportunity would never come again—all the chess pieces were in place. He had enough combat power for one more major effort to win the field. His troops had come so close to victory the day before. They had come this far, and to back away now would have been to admit defeat.

“It would be a bad thing if I could not rely on my brigade and division commanders. I plan and work with all my might to bring the troops to the right place at the right time. With that, I have done my duty... on the day of battle I lay the fate of my army in the hands of God.”

—Robert E. Lee

Lieutenant Haskell remembered the moment Lee’s guns opened fire on Cemetery Ridge just before 1:00 pm:

Major General James Johnston Pettigrew

We dozed in the heat, and lolled upon the ground, with half open eyes. Our horses were hitched to the trees munching some oats. A great lull rests upon all the field. Time was heavy, and for want of something better to do, I yawned, and looked at my watch. It was five minutes before one o’clock.

What sound was that? There was no mistaking it. The distinct sharp sound of one of the enemy’s guns.. .In an instant, before a word was spoken, as if that was the signal gun for general work, loud, startling, booming, the report of gun after gun in rapid succession smote our ears and their shells plunged down and exploded all around us. We sprang to our feet. In briefest time the whole Rebel line to the West was pouring out its thunder and its iron upon our devoted crest. From the Cemetery to Round Top, with over a hundred guns, and to all parts of the enemy’s line, our batteries reply .. . To say that it was like a summer storm, with the crash of thunder, the glare of lightning, the shrieking of the wind, and the clatter of hailstones, would be weak. The thunder and lightning of these two hundred and fifty guns and their shells, whose smoke darkens the sky, are incessant, all pervading, in the air above our heads, on the ground at our feet, remote, near, deafening, ear-piercing, astounding; and these hailstones are iron, charged with exploding fire ...

War correspondent Charles Coffin was at Meade’s headquarters when the firing began and later recalled:

Every size and form of shell known to British and to American gunnery shrieked, whirled, moaned, and whistled, and wrathfully fluttered over our ground. As many as six in a second, constantly two in a second, bursting and screaming over and around the head-quarters, made a very hell of fire that amazed the oldest officers. They burst in the yard,—burst next to the fence on both sides, garnished as usual with the hitched horses of aides and orderlies. The fastened animals reared and plunged with terror. . . sixteen lay dead and mangled before the fire ceased. . .

A shell tore up the little step at the head-quarters cottage, and ripped bags of oats as with a knife. Another soon carried off one of its two pillars. Soon a spherical case burst opposite the open door,—another ripped through the low garret. The remaining pillar went almost immediately to the howl of a fixed shot...

Forty minutes,—fifty minutes,— counted watches that ran, O so languidly! Shells through the two lower rooms. A shell into the chimney, that daringly did not explode. Shells in the yard. The air thicker, and fuller, and more deafening with the howling and whirring of these infernal missiles...

A shell exploding in the cemetery, killed and wounded twenty-seven men in one regiment! And yet the troops, lying under the fences, —stimulated and encouraged by General Howard, who walked coolly along the line,—kept their places and awaited the attack.

Amid this chaos, Hancock calmly rode his horse behind the ranks of his infantry taking cover along the wall. His calm, determined fearlessness was an inspiration to his men. When a subordinate officer complained of the risks he was taking Hancock replied, “There are times when the life of a corps commander does not count.”

As Pickett’s Charge was about to move forward, Stuart led his entire cavalry division south from the York Pike toward the rear of the Union army. Stuart’s cavalry would then circle behind the Union lines and cause havoc by attacking from behind. If Stuart could capture and hold the Baltimore Pike behind Culp’s Hill, it would sever the enemy’s communications and supply. Combined with Pickett’s assault this attack posed a mortal threat to the Union army if properly executed.

Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com.

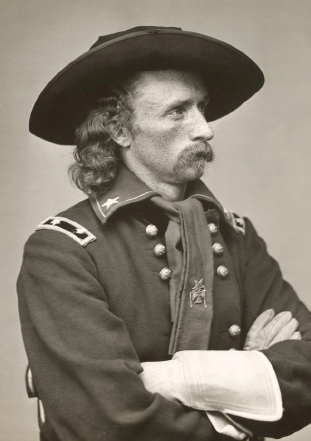

Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer. Photo credit: George L. Andrews, National Archives.

Directly in Stuart’s path, however, were two brigades of union cavalry under Brigadier General David M. Gregg. One was commanded by Colonel John B. Mclntosh and the other was a newly formed 7th Cavalry from Michigan under a firebrand officer Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer.

As the 1st Virginia Cavalry charged across a field to attack Union skirmishers, Gregg ordered Custer to lead a counter attack. Custer led his regiment forward crying, “Come on, you Wolverines!”

The ensuing combat between mounted cavalrymen was at point-blank range using sabers and pistols. Custer had his horse shot out from under him and without missing a beat, he took the mount of his bugler. The Virginians were forced back, only to have Stuart counterattack with troopers from all three of his brigades.

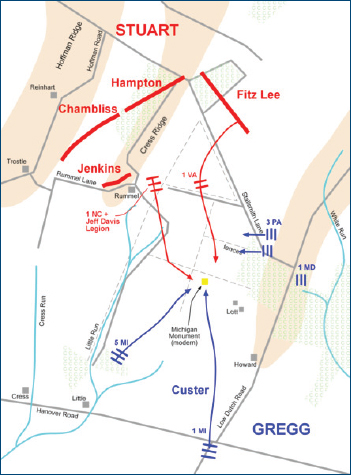

Gettysburg East Cavalry Field, final actions. Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com.

Come on, you Wolverines! Custer leads the Michigan Brigade, Gettysburg—July 3, 1863. Illustrated by Don Troiani.

Again, Custer led the charge to meet the rebel horsemen midfield. A trooper remembered, “As the two columns approached each other the pace of each increased, when suddenly a crash, like the falling of timber, betokened the crisis. So sudden and violent was the collision that many of the horses were turned end over end and crushed their riders beneath them.”

Attacked on three sides the Confederate forces were forced to pull back. Custer’s brigade had lost over 200 men, and Stuart’s command almost as many. But the fight was over. Stuart’s cavalry had been stopped, and the threat to the Union rear was squelched. Pickett’s infantry, about to make their assault on Cemetery Ridge a few miles away, would have to win the day on their own.

Major General George Edward Pickett

On Seminary Ridge the Confederate guns were nearing the end of their ammunition. Colonel Alexander, who was in command of the guns, knew he had to retain some ammunition to support the infantry. He sent a message to Longstreet that the time for the infantry attack had come. Pickett delivered the message to Longstreet, as Porter later noted: “Longstreet read it, and said nothing. Pickett said, ‘General, shall I advance?’ Longstreet, knowing it had to be, but unwilling to give the word, turned his face away. Pickett saluted and said, ‘I am going to move forward, sir,’ galloped off to his division and immediately put it in motion.”

As the guns fell silent a Confederate officer remembered, “A deathlike stillness then reigned over the field, and each army remained in breathless expectation of something yet to come still more dreadful.”

“General Pickett commands one of the divisions in Longstreet’s corps. He wears his hair in long ringlets, and is altogether rather a desperate looking character.”

—Colonel Arthur James Lyon Fremantle

For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it’s all in the balance, it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet, it not only hasn’t begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and those circumstances which made more men than Garnett and Kemper and Armistead and Wilcox look grave yet it’s going to begin, we all know that, we have come too far with too much at stake and that moment doesn’t need even a fourteen-year-old boy to think This time. Maybe this time with all this much to lose than all this much to gain: Pennsylvania, Maryland, the world, the golden dome of Washington itself to crown with desperate and unbelievable victory the desperate gamble, the cast made two years ago.

—William Faulkner, Intruder in the Dust

Lieutenant Haskell noted the moment along the Union lines: “The artillery fight over, men began to breathe more freely, and to ask, ‘What next, I wonder?’ The battery men were among their guns, some leaning to rest and wipe the sweat from their sooty faces, some were handling ammunition boxes and replenishing those that were empty. Some batteries from the artillery reserve were moving up to take the places of the disabled ones; the smoke was clearing from the crests.”

Suddenly there was a shout—”Here they come!

Quickly the ranks of three Confederate divisions, over 12,000 men, moved through the woods and arrayed themselves for battle nearly a mile from the Union line. As the units stood in their brigades along the forest line, Pickett rode before the ranks of his division, and yelled, “Up, Men, and to your posts! Don’t forget today that you are from Old Virginia!” The troops raised their hats and cheered as others gave the famous rebel yell.

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com.

The Confederate brigades planned to advance by marching almost a mile across the open fields, not stopping to fire until they reached the Emmitsburg Road, which lay two hundred yards from the Union line. All units would converge at the center of the Union line where a small copse of trees stood at a corner of the stone wall, forever known afterward as “the Angle.” If the artillery had silenced the Union guns the infantry could then advance and attack Cemetery Ridge to split the Union line in two. Hill’s corps was held in reserve to reinforce any breakthrough. Success or failure now rested entirely on the infantry.

“Regiment after regiment and brigade after brigade move from the woods and rapidly take their places in the lines forming the assault,” reported Haskell. “More than half a mile their front extends; more than a thousand yards the dull gray masses deploy, man touching man, rank pressing rank, and line supporting line. The red flags wave, their horsemen gallop up and down; the arms of eighteen thousand men, barrel and bayonet, gleam in the sun, a sloping forest of flashing steel. Right on they move, as with one soul, in perfect order, without impediment of ditch, or wall or stream, over ridge and slope, through orchard and meadow, and cornfield, magnificent, grim, irresistible.”

Rock of Erin, July 3, 1863. The 69th Pennsylvania volunteer infantry defends Cemetery Ridge from. Pickett’s Charge. Illustrated by Don Troiani.

Waiting for the Confederates along the Union line were massed infantry four-ranks deep in some places, laying flat behind the wall with loaded muskets, ready for the time when the enemy would be within range. Charles Coffin witnessed the advance: “Every man was on the alert. The cannoneers sprang to their feet. The long lines emerged from the woods, and moved rapidly but steadily over the fields, toward the Emmitsburg road. Howard’s batteries burst into flame, throwing shells with the utmost rapidity. There are gaps in the Rebel ranks, but onward still they come.”

They were at once enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke and dust. Arms, heads, blankets, guns and knapsacks were thrown and tossed in to the clear air.... A moan went up from the field, distinctly to be heard amid the storm of battle.

—Lieutenant Colonel Franklin Sawyer, 8th Ohio

Lieutenant Finley of Pickett’s Division later wrote, “Still on, steadily on, with the fire growing more furious and deadly, our men advanced ... as we neared the Emmitsburg Road, the Federals behind the stone fence on the hill opened a rapid fire upon us with muskets . . . Men were falling all around....”

As the Confederates reached the Emmitsburg Road they encountered a strong rail fence lining each side of the lane that could not be pulled down. As the Confederates climbed over the obstacle, the Union defenders fired volley after volley of musketry into their ranks. Devastated, some rebel units, unable to sustain the terrible losses, began to retreat. Others were cut down in entire rows by enfilading artillery fire raining down from Little Round Top and from batteries firing canister to their front.

Yet, behind the leading units in the Confederate formation were additional brigades in support. Among these was the brigade led bv Lewis Armistead. At the road, the decimated Confederates returned massed volleys of their own toward the blue coats 200 yards away, both sides enveloped in smoke and fire.

Brigadier General Lewis Addison Armistead

Amid the carnage General Hancock took a bullet to the thigh and was lowered from his horse. A tourniquet was applied to prevent him from bleeding to death, but he refused evacuation until the battle had been decided.

High Water Mark—July 3, 1863. Lewis Armistead leads the attack over the stone wall at the Angle. Illustrated by Don Troiani.

Not far away, Hancock’s best friend, Armistead, his black hat raised upon the tip of his sword, led the survivors of Pickett’s Charge the last 200 yards to the wall at the copse of trees. With their ranks decimated by rifle and canister fire, Armistead knew the moment of decision was at hand. Turning to his men, sword raised, he yelled above the deafening roar of battle, “Come forward, Virginians! Come on, boys, we must give them the cold steel! Who will follow me?”

Lieutenant Finley advanced with Armistead and later recalled, “When we were about seventy-five or one hundred yards from that stone wall, some of the men holding it began to break for the rear, when, without orders, save from captains and lieutenants, our line poured a volley or two into them, and then rushed the fence ... The Federal gunners stood manfully to their guns. I never saw more gallant bearing in any men. They fired their last shots full in our faces and so close that I thought I felt distinctly the flame of the explosion.”

With a chilling rebel yell, the Confederates swept over the stone wall and captured the Union battery placed near the Angle driving the defending infantry back from their wall. War correspondent Charles Coffin witnessed the action:

Men fire into each other’s faces, not five feet apart. There are bayonet-thrusts,

saber-strokes, pistol-shots... hand-to-hand contests ... men going down on their hands and knees, spinning round like tops, throwing out their arms, gulping up blood, falling; legless, armless, headless. There are ghastly heaps of dead men. Seconds are centuries; minutes, ages; but the thin line does not break!

The Rebel column has lost its power. The lines waver. The soldiers of the front rank look round for their supports. They are gone,—fleeing over the field, broken, shattered, thrown into confusion by the remorseless fire from the cemetery and from the cannon on the ridge. The lines have disappeared like a straw in a candle’s flame. The ground is thick with dead, and the wounded are like the withered leaves of autumn. Thousands of Rebels throw down their arms and give themselves up as prisoners.

Armistead went down with wounds to his arm and leg just moments after storming the wall. Captured by Union soldiers, he was carried on a blanket to the rear where he was met by Captain Henry Bingham, an officer on Hancock’s staff who later wrote to Hancock of the exact exchange:

I dismounted my horse and inquired of the prisoner his name. He replied General Armistead of the Confederate Army. Observing that his suffering was very great I said to him, General,

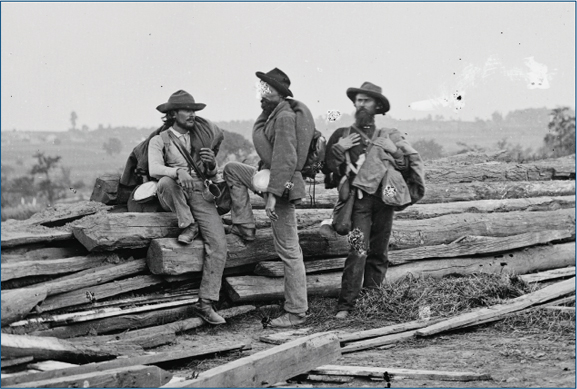

Three Confederates taken prisoner at Gettysburg posed for this photo a few days after the battle. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

“If the men I had the honor to command that day could not take that position, all hell couldn’t take it.”

—Major General Isaac Trimble

I am Captain Bingham of General Hancock’s staff, and if you have anything valuable in your possession which you desire taken care of, I will take care of it for you.

He then asked me if it was General Winfield S. Hancock and upon my replying in the affirmative, he informed me that you were an old an valued friend of his and he desired for me to say to you, “Tell General Hancock for me that I have done him and done you all an injury which I shall regret the longest day I live.” I then obtained his spurs, watch chain, seal and pocketbook. I told the men to take him to the rear to one of the hospitals.

Along the Union line the soldiers knew that they had at last won a decisive victory over their adversary, who had whipped them time and again until this day. Thousands took up the taunting chant, “Fredericksburg! Fredericks-burg!” upon the shattered legions of Lee’s army as they stumbled back toward Seminary Ridge. The Confederates had suffered over 50 percent casualties, including over 3,000 men taken prisoner. The copse of trees at the Angle would go down in history as the high-water mark of the Confederacy—the farthest advance of their army, and also perhaps the closest the South ever came to winning its independence.

Lee, watching the disaster unfold from Seminary Ridge, rode out alone to meet the survivors as they streamed back to the trees. Alexander Porter noted, “Lee, as a soldier, must have at this moment have foreseen Appomattox—that he must have realized that he could never again muster so powerful an army, and that for the future he could only delay, but not avert, the failure of his cause.” Yet Lee showed no anger, fear, or disappointment of any kind as he reached out to his wounded soldiers and told them, “This has all been my fault.” Colonel Fremantle, who witnessed Lee’s actions, was awed by his strength of presence and character:

He was engaged in rallying and in encouraging the broken troops, and was riding about a little in front of the wood, quite alone—the whole of his Staff being engaged in a similar manner further to the rear. His face, which is always placid and cheerful, did not show signs of the slightest disappointment, care, or annoyance; he was addressing to every soldier he met a few words of encouragement, such as, “All this will come right in the end: we’ll talk it over afterwards; but, in the mean time, all good men must rally. ”

I never saw troops behave more magnificently than Pickett’s division of Virginians did today in that grand charge upon the enemy. And if they had been supported as they were to have been,—but, for some reason not fully explained to me, were not—we would have held the position and the day would have been ours.

—Robert E. Lee

He spoke to all the wounded men that passed him, and the slightly wounded he exhorted “to bind up their hurts and take up a musket” in this emergency. Very few failed to answer his appeal, and I saw many badly wounded men take off their hats and cheer him. He said to me, “This has been a sad day for us, Colonel—a sad day; but we can’t expect always to gain victories. ”

I saw General Wilcox come up to him, and explain, almost crying, the state of his brigade. General Lee immediately shook hands with him and said cheerfully, “Never mind, general, all this has been MY fault— it is I that have lost this fight, and you must help me out of it in the best way you can.” In this manner I saw General Lee encourage and reanimate his somewhat dispirited troops, and magnanimously take upon his own shoulders the whole weight of the repulse. It was impossible to look at him or to listen to him without feeling the strongest admiration.

Pickett was equally devastated at seeing his proud division cut down before his eyes by enemy fire. When approached by Lee to reform his division he replied, “General Lee—I have no division.”

Fearing an enemy counterattack, Lee pulled together his shattered brigades in a defensive line, but the Union troops never came. The Army of the Potomac had suffered equal losses over the past three days of this epic battle and was content to see the rebels go. Lieutenant Haskell had the honor of informing Meade that the day had been won:

General Meade rode up ... no bedizened hero of some holiday review, but he was a plain man, dressed in a serviceable summer suit of dark blue cloth, without badge or ornament, save the shoulder-straps of his grade, and a light, straight sword of a General. . . . his soft black felt hat was slouched down over his eyes. His face was very white, not pale, and the lines were marked and earnest and full of care. As he arrived near me, coming up the hill, he asked, in a sharp, eager voice: “How is it going here?” “I believe, General, the enemy’s attack is repulsed,” I answered.

By this time he was on the crest, and when his eye had for an instant swept over the field, taking in just a glance of the whole—the masses of prisoners, the numerous captured flags which the men were derisively flaunting about, the fugitives of the routed enemy, disappearing with the speed of terror in the woods—partly at what I had told him, partly at what he saw, he said, impressively, and his face lighted: “Thank God. ”