Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just...

—Thomas Jefferson

Even before the guns cooled that hot third day of July a new crisis was at hand—the plight of the wounded. Gettysburg was now a manmade disaster unparalleled in American history. Over 20,000 men from both sides lay on the fields or crammed into any available shelter. Every church, private home, barn, stable, pigsty, or shed in and around the town was filled with critically wounded and dying men. Thousands of dead soldiers and horses were scattered for miles in the surrounding fields and woods. The wells had all been pumped dry by thirsty soldiers. As the armies separated themselves from combat, a new battle began in earnest—to rescue the survivors of both sides.

Tillie Pierce, along with Mrs. Weikert and her children, had been evacuated earlier that day to a farm down the Taneytown Road near Two Taverns. By late afternoon they realized the sounds of battle were over and decided to make their way back to the Weikert’s home. Tillie recounted in her diary:

As we drove along in the cool of the evening, we noticed that everywhere confusion prevailed. Fences were thrown down near and far; knapsacks, blankets and many other articles, lay scattered here and there. The whole country seemed filled with desolation.

Upon reaching the place I fairly shrank back aghast at the awful sight presented. The approaches were crowded with wounded, dying and dead. The air was filled with moanings, and groanings. As we passed on toward the house, we were compelled to pick our steps in order that we might not tread on the prostrate bodies.

When we entered the house we found it also completely filled with the wounded. We hardly knew what to do or where to go. They, however, removed most of the wounded, and thus after a while made room for the family.

As soon as possible, we endeavored to make ourselves useful by rendering assistance in this heartrending state of affairs. I remember that Mrs. Weikert went through the house, and after searching awhile, brought all the muslin and linen she could spare. This we tore into bandages and gave them to the surgeons, to bind up the poor soldier’s wounds.

By this time, amputating benches had been placed about the house. I must have become inured to seeing the terrors of battle, else I could hardly have gazed upon the scenes now presented. I was looking out one of the windows facing the front yard. Near the basement door, and directly underneath the window I was at, stood one of these benches. I saw them lifting the poor men upon it, then the surgeons sawing and cutting off arms and legs, then again probing and picking bullets from the flesh.

Some of the soldiers fairly begged to be taken next, so great was their suffering, and so anxious were they to obtain relief.

To the south of the house, and just outside of the yard, I noticed a pile of limbs higher than the fence. It was a ghastly sight! Gazing upon these, too often the trophies of the amputating bench, I could have no other feeling, than that the whole scene was one of cruel butchery.

Twilight had now fallen; another day had closed; with the soldiers saying, that they believed this day the Rebels were whipped, but at an awful sacrifice.

Saturday dawned and quickly the temperature rose as another hot and humid afternoon approached. The two armies were bloodied and battered—like two prize fighters unwilling to continue the contest—and stood a healthy distance from each other across the valley. Lee hoped Meade would attack and give the Confederates a chance to reclaim some measure of victory over the Union army, but Meade knew his shattered brigades were in no condition to advance though they had certainly won a great and decisive victory.

The Jacob Weikert House where Tillie assisted the doctors and the wounded. Photo credit: The Gettysburg Daily.

Tillie remembered that day as well: “On the summits, in the valleys, everywhere we heard the soldiers hurrahing for the victory that had been won. The troops on our right, at Culp’s Hill, caught up the joyous sound as it came rolling on from the Round Tops on our left, and soon the whole line of blue, rejoiced in the results achieved.” Most befitting of all, it was the fourth of July. By afternoon word had come that Vicksburg had surrendered to General Grant’s army in Mississippi. It seemed as if the Union victory was complete; that the war might soon be over.

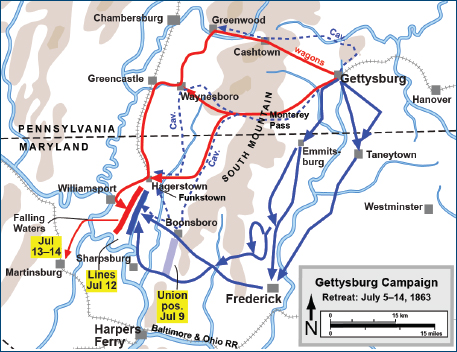

Lee wasted no time in making plans and issuing orders for his wounded army to retreat back through the Cashtown Gap and across the Potomac back into Virginia. The Army of Northern Virginia had lost a major battle, but they were not a defeated army. The prevailing mood of the Confederate troops was that the enemy’s superior position had been the key to their undoing on July 3. But some blamed Lee and his officers for making Pickett’s Charge in the first place. One was heard to say, “If Old Jack had been here, it wouldn’t have been like this.” The time for recriminations would come later. The task at hand was one of escape.

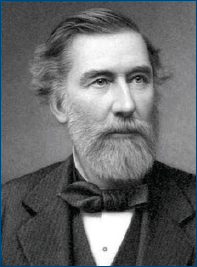

Brigadier General John Imboden

Lee summoned Brigadier General John Imboden, a cavalry officer whose troopers had been protecting Lee’s supply wagons in Cham-bersburg. Imboden was given command of a wagon train that would take the wounded who could be moved back to Virginia. Lee’s troops would follow along a different route. Low on ammunition and with ranks decimated by three days of hard fighting, Lee was in a dangerous situation. To retreat with so many wounded in the face of the enemy would take all his skill as a commanding general. If his army became trapped on the northern side of the Potomac, it could face total destruction if Meade’s army attacked.

Around noon, the sky opened and let loose a howling thunderstorm, drenching the wounded who were unable to find shelter and turned the fields of battle into muddy swamps. Major General Carl Schurz remembered, “A heavy rain set in during the day—the usual rain after a battle—and large numbers had to remain unprotected in the open, there being no room left under roof. I saw long rows of men laying under the eaves of the buildings, the water pouring down upon their bodies in streams.”

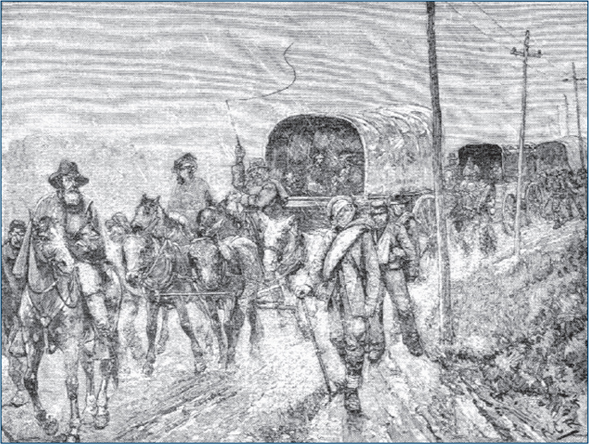

The storm made Imboden’s task to command the wagon train of wounded even more difficult. He later wrote, “The very windows of heaven seemed to have opened . . . The deafening roar of the mingled sounds of heaven and earth all around made it almost impossible to communicate orders, and equally difficult to execute them.” Around 4:00 PM, the vast column of wagons began to move out. Imboden’s orders were to get to Williamsport with all haste. There the men and horses would rest before crossing the Potomac. His 1,200 wagons were filled to capacity with wounded men.

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com.

Imboden wrote of the retreat that night:

The column moved rapidly, considering the rough roads and the darkness, and from almost every wagon for many miles issued heart-rending wails of agony . . . Scarcely one in a hundred had received adequate surgical aid, owing to the demands on the hardworking surgeons from still worse cases that had to be left behind. . .

Some were only moaning; some were praying, and others uttering the most fearful oaths and execrations that despair and agony could wring from them; while a majority, with a stoicism sustained by sublime devotion to the cause they fought for, endured without complaint unspeakable tortures, end even spoke words of cheer and comfort to their unhappy comrades of less will or more acute nerves.

A Vast Procession of Misery by Allen Christian Redwood.

No heed could be given to any of their appeals. Mercy and duty to the many forbade the loss of a moment in the vain effort then and there to comply with the prayers of a few. On! On! We must move on.

On the night of July 4, Ewell’s troops, who were still occupying Gettysburg, quietly prepared to withdraw. The townspeople had heard the massive bombardment and gunfire of the previous afternoon, but no one knew for sure what it all meant. Resident Sarah Broadhead noted the change of mood among the rebel soldiers in her diary: “Who is victorious, or with whom the advantage rests, no one can tell. It would ease the horror if we knew our arms were successful. Some think the Rebels were defeated, as there has been no boasting as on yesterday, and they look uneasy and by no means exultant.”

Daniel Skelly knew something was afoot and could not sleep that night:

On this night, I went to bed restless and was unable to sleep soundly. About midnight I was awakened by a commotion down in the street. Getting up I went to the window and saw Confederate officers passing through the lines of Confederate soldiers bivouacked on the pavement below, telling them to get up quietly and fall back. Very soon the whole line disappeared but we had to remain quietly in our homes for we did not know what it meant.

About 4 AM, there was another commotion in the street, this time on Baltimore, the Fahnestock building being at the corner of West Middle and Baltimore Streets. It seemed to be a noisy demonstration. Going hurriedly to the window I looked out. Ye gods! What a welcome sight for the imprisoned people of Gettysburg! The Boys in Blue marching down the street, fife and drum corps playing, the glorious Stars and Stripes fluttering at the head of the lines.

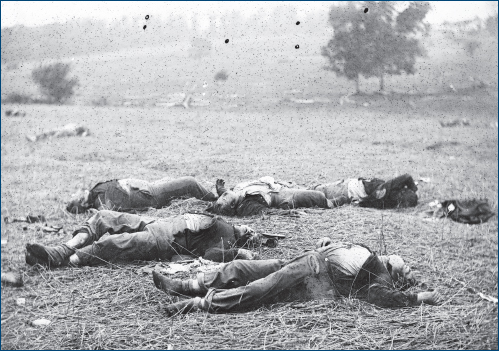

As Lee’s army withdrew toward the Potomac, he surrendered 4,000 wounded men to Union care. The following day, as Meade’s army moved out in pursuit of Lee, most of the army doctors went with the troops. Almost overnight, a town of 2,000 residents and a handful of surgeons was left in charge of more than 20,000 wounded men in dire need of care. The task of burying the dead also remained. The devastation—both of people and property—in and around Gettysburg was beyond description.

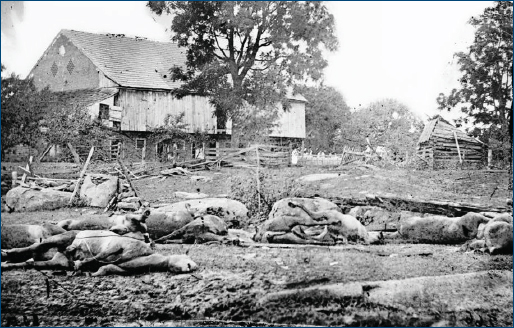

The bodies of Union soldiers killed during the fighting on July 1, near McPherson’s Woods, await burial. Photo credit: Timothy H. O’Sullivan, National Archives.

The Trostle barn near the Peach Orchard after the battle. The dead horses belonged to an artillery battery. Photo credit: National Archives.

The townspeople and volunteers from miles around came to Gettysburg to render aid. The government’s Sanitary Commission, an organization similar to today’s Red Cross, arrived almost immediately, setting up tents and organizing relief efforts. The wounded were eventually collected into improvised hospitals in tents and buildings where they received medical care until they were well enough to be discharged, moved to a proper hospital, or in the case of the Confederates to prison camps. In these relief efforts the Union wounded received aid first, but once under the care of a doctor, wounded Confederate soldiers were generally treated with the same care as their Union counterparts.

The dead, by necessity, could not receive such tender care. Strewn over miles of the battlefield and lying out for days in the July sun, most of the dead were unrecognizable. Neither army issued “dog tags” or any formal means of identification for the soldiers at that time. Men sometimes sewed their names onto a jacket, or scribbled their names, units, and addresses onto the inside cover of a diary they often carried, but that was the only means of identification at that time. The U.S. government also did not have a formal means of notifying the next of kin that a man had fallen in battle, so many men simply disappeared, buried in mass graves with others from their unit wherever they were killed on a battlefield.

The graves of Confederate soldiers await completion after the battle. Photo credit: Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Library of Congress.

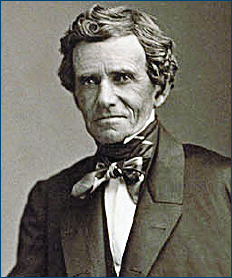

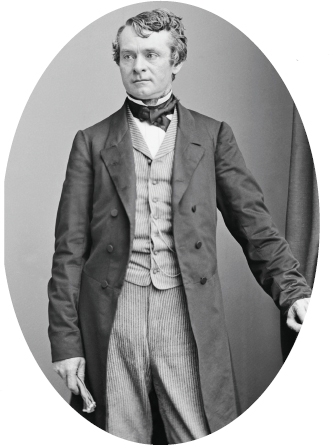

Samuel Wilkeson of the New York Times.

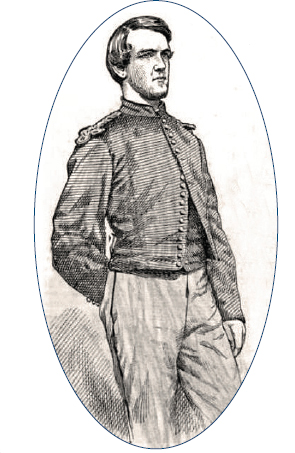

Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson

Tillie and Daniel were witness to the devastation wrought upon their quiet town following the battle. Tillie ventured out with her friend Beckie Weikert on July 5, escorted by an army lieutenant, to visit the summit of Little Round Top: “As we stood upon those mighty boulders, and looked down into the chasms between, we beheld the dead lying there just as they had fallen during the struggle. From the summit of Little Round Top, surrounded by the wrecks of battle, we gazed upon the valley of death beneath. The view there spread out before us was terrible to contemplate! Dead soldiers, bloated horses, shattered cannon and caissons, thousands of small arms. In fact everything . . . was there in one confused and indescribable mass.”

Daniel walked to the Round Tops from town the following day and noted that “the whole v countryside was covered with ruins of the battle. One of the saddest sights of the \ day’s visit on the field I witnessed near the Devil’s Den, on the low ground in that vicinity. There were twenty-six Confederate officers, ranking from a colonel to lieutenants, laid side by side in a row for burial. At the head of each was a board giving their names, ranks and commands to which they belonged . . . They had evidently been prepared for burial by their Confederate companions before they had fallen back, so that their identity would be preserved, and they would receive a respectable burial.”

Among the masses of people heading toward Gettysburg after the battle were relatives of soldiers coming to search for their loved ones while there was still time. One such search immediately gripped the nation. Sam Wilkeson, a war correspondent for the New York Times, had arrived at Gettysburg on July 2, to report on the epic battle. Both of his sons were in the Union army, including Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson of Battery G, 4th U.S. Artillery. This unit had been overrun at Barlow’s Knoll on the first day’s fighting, covering the retreat of the Eleventh Corps. Learning that his son had been killed in action Sam Wilkeson went to look for him after the battle had ceased.

Finding his son’s mangled corpse and learning of the desperate circumstances of his death, Sam Wilkeson sat next to the body and wrote an angry dispatch to his paper: “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a central figure of transcendingly absorbing interest— the dead body of an oldest born son, crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not to stay.” His writing touched the hearts of millions.

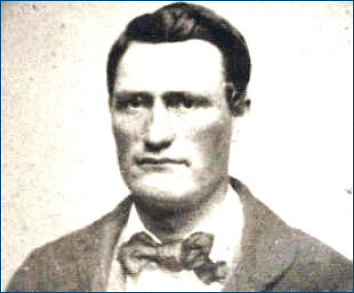

As the Gettysburg townspeople began burying the dead, the body of a Union soldier was discovered tucked off a street where he had crawled, mortally wounded, to die. His jacket had no badges, no signs of rank or unit, and his pockets contained nothing to identify him—no letters or diary. Yet in his hand he grasped a small photo of three young children. The last act of his life had been to gaze upon their faces.

The photo came into the possession of Dr. J. Francis Bourns, a Philadelphia doctor on his way to help the wounded from the battlefield. He hoped to locate the mother of the children in the photograph by publishing a detailed description of them in all the local papers. A major story ran in the Philadelphia Inquirer on October 19, 1863, entitled, “Whose Father Was He?” As the story grew in fame and as the photo of the children was printed onto thousands of small post cards, the nation waited in suspense. Would anyone identify the children?

Dr. Bourns soon received a letter from a woman in Portville, New York, who had not heard from her husband since the battle of Gettysburg. She requested a copy of the photograph. When she received it in the mail she looked upon the faces of her three children—Franklin, Alice, and Frederick—who were now fatherless. The woman’s name was Phylinda Humiston. Her fallen husband was Sergeant Amos Humiston of Company C, 154th New York Volunteers. Sergeant Humiston came to symbolize the thousands of missing men at Gettysburg and other battles, whose widows and orphaned children waited for them in vain.

Sergeant Amos Humiston

“The Children of the Battlefield, “ later identified as Frank, Frederick, and Alice Humiston.

To My Wife

You have put the little ones to bed dear wife

And covered them over with care

My Frankey Alley and Fred

And they have said their evening prayer

Perhaps they breathed the name of one

Who is far in southern land

And wished he too were there

To join their little band

I am very sad to tonight dear wife

My thoughts are dwelling on home and thee

As I keep the lone night watch

Beneath the holly tree

The winds are sighing through the trees

And as they onward roam

They whisper hopes of happiness

Within our cottage home

And as they onward passed

Over hill and vale and bubbling stream

They wake up thoughts within my soul

Like music in a dream

Oh when will this rebellion cease

This cursed war be over

And we our dear ones meet

To part from them no more?

—Amos Humiston, March 25th 1863

Three years after the battle, an orphanage was established at Gettysburg—called The Homestead Association—for the benefit of children whose fathers had been killed in the service of their country. Mrs. Humiston and her children were among the first to reside at the home. James Garfield, future president of the United States, was on the board of trustees. Dr. Bourns served as the first general secretary. The founding of the orphanage was reported nationwide for a citizenry still trying to understand the meaning of the great sacrifices made during the Civil War.

Amid all the human agony and loss during those first days of July 1863, there was at least one happy homecoming as Tillie Pierce made her way back to Gettysburg and to her father’s house on Baltimore Street:

Sometime during the forenoon of Tuesday, the 7th, in company with Mrs. Schriver and her two children, I started off on foot to reach my home.

As it was impossible to travel the roads, on account of the mud, we took to the fields. While passing along, the stench arising from the fields of carnage was most sickening. Dead horses, swollen to almost twice their natural size, lay in all directions, stains of blood frequently met our gaze, and all kinds

of army accoutrements covered the ground. Fences had disappeared, some buildings were gone, others ruined. The whole landscape had been changed, and I felt as though we were in a strange and blighted land.

I hastened into the house. Everything seemed to be in confusion, and my home did not look exactly as it did when I left. Large bundles had been prepared, and were lying around in different parts of the room I had entered. They had expected to be compelled to leave the town suddenly. I soon found my mother and the rest. At first glance even my mother did not recognize me, so dilapidated was my general appearance. The only clothes I had along had by this time become covered with mud, the greater part of which was gathered the day on which we left home.

As soon as I spoke my mother ran to me, and clasping me in her arms, said: “Why, my dear child, is that you? How glad I am to have you home again without any harm having befallen you!

Daniel and his friends realized the aftermath of the great battle would be one of a more businesslike opportunity as around 60,000 new customers were camped within the Union lines just outside town:

My friend “Gus” Bentley met me on the street and told me that down at the Hollinger warehouse where he was employed they had a lot of tobacco. “We hid it away before the Rebs came into town, “ he continued, “and they did not find it. We can buy it and take it out and sell it to the soldiers.” Like all boys of those days we had little spending money but we concluded we would try and raise the cash in some way.

I went to my mother and consulted her about it and she loaned me ten dollars. Gus also got ten, all of which we invested in the tobacco. It was in large plugs—Congress tobacco, a well known brand at that time. With an old-fashioned tobacco cutter we cut it up into ten cent pieces and each of us took a basket full and started out Baltimore Street to the cemetery, the nearest line of battle.

The soldiers helped us over the breastworks with our baskets and in a short time they were empty and our pockets filled with ten-cent pieces. The soldiers told us to go home and get some more tobacco, that they would buy all we could bring out. We made a number of trips, selling out each time, and after disposing of all our supply, and paying back our borrowed capital, we each had more money than we ever had before in our lives.

Young Daniel would play an even more important role in the recovery efforts in the following weeks, though:

In the days following the battle, the firm of Fahnestock Brothers received numerous inquires about wounded soldiers who were scattered over the field in the hospitals hastily set up at points most conveniently located to take care of the casualties. With Mrs. E. G. Fahnestock, I frequently rode back and forth among these stations, either in buggy or on horseback, looking for wounded men about whom information was sought. Sometimes it was difficult to locate them. We made other trips to the hospitals in the college and seminary buildings also. Frequently on these trips were included supplies of delieacte’s for the men. So it was that the people of Gettysburg assisted in every way in solving the problems that arose incident to the great battle.

Plans for a national cemetery for the Union dead were put into action soon after the battle. Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin ordered his agent, attorney David Wills, to acquire the Evergreen Cemetery and its surrounding land as a final resting place for more than 3,000 Union soldiers. William Saunders, a famous landscape architect, was commissioned to design the cemetery. He placed the fallen in rows of sweeping arcs, giving each state equal prominence. In early November, Union remains were transferred from their original burial sites to the graves within the cemetery.

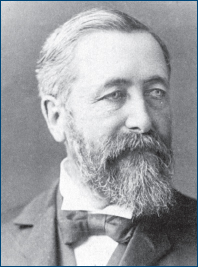

David Will.

Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin. Photo credit: Matthew Brady, Library of Congress.

William Saunders

A dedication for the Soldiers National Cemetery was planned for November 19, 1863, and David Wills invited the statesman Edward Everett, a premier orator of that time, to give the keynote speech. Only three weeks before the dedication, Wills also invited President Lincoln to attend and give “a few appropriate remarks” following Everett’s speech.

Lincoln began planning his remarks with care. He looked to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution for inspiration. The American people would expect him to provide some kind of meaning to their great sacrifices in a war nearing its third year with no end in sight. Lincoln would be speaking to a nation that would decide in one year if they would re-elect him as president. Many had underestimated Lincoln in the past, but no one realized he was about to make the greatest speech in American history, in just 272 words.