TUESDAY, MAY 17, 2011. We awaken to find fair May overthrown, her sweet state usurped by an illegitimate and bullying November. Rain falls in sheets, often flung in our faces by sudden squalls, and the mild temperatures of our first week are mere teasing memories. But I enjoy the thought that we will be experiencing Hamburg rather as a sardonic anonymous traveler described its weather back in the eighteenth century, calling it “on the whole somewhat raw, damp and cold most days of the year, just like most of the people.” Alex and Helmut had a similar climatological encounter on a May day in 1939 during their one visit to Hamburg, when they thought they were bidding their final farewells to their European lives.

We drive our Meriva to the Oldenburg Bahnhof, or train station, and purchase, for twenty-nine euros, a ticket that would allow Amy and me to travel anywhere by train throughout Lower Saxony and as far east as Hamburg, and to take as many rail journeys as we’d like, between 9:00 a.m. today and 3:00 a.m. tomorrow. We are deeply impressed by this evidence of Germany’s support for public transportation We consult the bright-yellow schedules that adorn the central waiting area, and learn that we can board a train on Track 7 at 9:46, arrive in Bremen at 10:39, change trains, and pull into Hamburg at 11:42, having traveled a distance of roughly two hundred kilometers. At precisely 9:46, I discover, and not for the first time, that in Germany the trains do indeed run on time.

Our train to Bremen is a local that stops at several hamlets along the way and in the larger community of Delmenhorst. My father used to tell me that, in his day, Delmenhorst was known as a linoleum manufacturing center and that you could always smell the nascent floor covering from the station. So as we roll into town, I lower a window and inhale deeply, but perhaps because of the wind and rain and perhaps because I have no idea what linoleum smells like, I notice nothing out of the ordinary.

I think of my father again during our brief stopover in the bustling train station in Bremen. As a boy, he frequently accompanied his mother on rail journeys to Bremen to visit her family of well-to-do coffee importers. As a child, he made many a visit to the city’s thirteenth-century St. Peter’s Cathedral and a single visit to the crypt of the eleventh-century Church of Our Lady, where he was so terrorized by its collection of mummified remains that he still shuddered to speak of it in his tenth decade of life.

Our next train leaves promptly—naturally—at 10:50 and pulls into the immense Hamburg Hauptbahnhof two minutes early. The Central Station, as it’s known in English, opened for business on St. Nicholas Day, 1906, and claims to be the busiest railway station in Germany and, after Paris, the second busiest in all Europe. Today, the hordes of Hamburgers thronging the station are made more imposing by the umbrellas they wield as they stride rapidly through the vast interior, which includes twenty separate tracks and an overhead emporium with restaurants, flower shops, bakeries, and a fully stocked pharmacy.

We find our way to the U-Bahn, or subway, and navigate the underground system for a distance of six stops, emerging at St. Pauli Landungsbrücken, just steps from the River Elbe. The foul weather surprises us anew with its undeniable rudeness. Leaning into a stiff wind, our eyes assaulted by sheets of horizontal rain, we trudge slowly down one of several movable bridges leading to the long landing pier that for more than a century and a half has been an embarkation point for transatlantic voyages. The tide is high, gulls wheel and shriek overhead, and the clouds and mist conspire together to reduce visibility to mere yards. Through the gloom, however, it is possible to see a neon sign on the opposite bank of the Elbe advertising a long-running production of the musical The Lion King.

The long pier, more than the length of seven football fields, was heavily bombed during the Second World War and rebuilt during the 1950s and ’60s. Despite today’s wind and weather, restaurants along the pier are serving English-style fish and chips and traditional German brews. Several hundred yards to the west, a sizable Greek tanker is tied up, and immediately in front of us, a small catamaran is readying for a tour to the island of Helgoland in the North Sea. It is, apparently, just a normal Tuesday on the Hamburg docks.

On such a day as this, I repeat to myself over and over, on a May evening seventy-two years ago, my grandfather and uncle set off on a voyage from this very spot—a voyage that was supposed to end in freedom for them and eventually for the whole Goldschmidt clan. I lean on a railing and squint through the wind and rain, trying to peer past the decades and conjure up a vision of their unfortunate vessel. There is water on my cheeks, the fresh mixing with the salt in the manner of the River Elbe giving way seventy miles downstream to the inexorable pull of the sea.

BEGINNING IN 1847, a new fleet of ships began weighing anchor from the port of Hamburg and sailing to destinations all over the globe. Most of the journeys ended in the New World, in Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Guayaquil, and Havana; in New Orleans, Baltimore, Boston, Montreal, Halifax, and New York City. These were the ships of the mighty Hamburg Amerikanische Packetfahrt Actien Gesellschaft—literally, the Hamburg American Packet-Shipping Joint Stock Company—or HAPAG for short, also known simply as the Hamburg-America Line. In the company’s early years, HAPAG ships made the crossing from Hamburg to New York via Southampton in forty days. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the journey had been reduced to less than a week.

Many celebrated ships flew the blue and white HAPAG flag. In September 1858, the SS Austria caught fire in the middle of the North Atlantic and sank, killing 463 of its 538 passengers. Among the survivors was Theodore Eisfeld, the music director of the New York Philharmonic, who had managed to lash himself to a plank and drifted on rough seas for two days and nights without food or water before being rescued. In 1900, the 16,500-ton SS Deutschland made history by sailing from Hamburg to New York in just over five days, maintaining a speed of twenty-two knots. Twelve years later, HAPAG’s Amerika was the first ship to send radio signals warning the luxury liner Titanic of icebergs in the vicinity.

But in the storied chronicles of the Hamburg-America Line, which merged in 1970 with Bremen’s North German Lloyd to form today’s Hapag-Lloyd Corporation, no ship rivals the infamy of the SS St. Louis. She was built by the Bremer-Vulkan Shipyards in Bremen, at the time the largest civilian shipbuilding company in the German Empire, and launched on May 6, 1928. Her maiden voyage, with stops in Boulognesur-Mer, France, and Southampton, England, en route to New York City, began on March 29, 1929. The St. Louis was among the largest ships in the entire HAPAG line, weighing 16,732 tons and measuring 575 feet in length. Diesel powered, gliding through the water on the strength of twin triple-bladed propellers, she regularly reached speeds of sixteen knots as she sailed the trans-Atlantic route from Hamburg to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and New York, and on occasional cruises to the Caribbean. Her cabins and tourist berths were designed to accommodate 973 passengers. She was, in every measure of the phrase, a luxury liner; her gleaming brochures proclaimed, “The St. Louis is a ship on which one travels securely and lives in comfort. There is everything one can wish for that makes life on board a pleasure.”

By the spring of 1939, the St. Louis had been serving its largely well-heeled clientele for ten years. The single voyage for which she remains most famous was about to commence, brought about by the confluence of several interlocking events.

On January 24, 1939, Nazi Field Marshal Hermann Göring appointed Reinhard Heydrich to direct the Central Office for Jewish Emigration. The Final Solution to what the Third Reich termed the Jewish Problem still lay several years in the future; for now the goal was simply to get as many Jews out of Germany as possible. Heydrich knew Claus-Gottfried Holthusen, the director of the Hamburg-America Line, and knew also that, since 1934, the Reich had become the majority shareholder in HAPAG, thus compromising the independence that the shipping company had enjoyed for the past ninety years. And Heydrich was aware that HAPAG had recently been troubled by financial setbacks exacerbated by the uncertain international situation. On its last voyage from New York, for instance, the St. Louis had sailed with only about a third of her berths occupied.

Heydrich immediately recognized an opportunity that would be mutually beneficial for the Reich and for HAPAG. He informed Göring and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels about the facts as he saw them, and by the middle of April, they had arranged that the St. Louis would sail from Hamburg to Havana, Cuba, on May 13, bearing nearly a thousand Jewish refugees. Everyone involved was satisfied. Göring relished the opportunity to demonstrate to Chancellor Hitler that he was ridding the Reich of Jews. Goebbels perceived the nearly perfect propaganda possibilities: Germans would be pleased that more Jews were leaving the country, while the international community, still shocked from the reports of Kristallnacht violence, would observe that Germany was graciously allowing its Jews to leave unharmed and unimpeded—and on a luxury liner, no less. The Hamburg-America Line would turn a profit on a voyage at a time when it sorely needed one. (While the St. Louis passengers would be refugees, to be sure, they would be charged the standard fares of 800 Reichsmarks for first class and 600 Reichsmarks for tourist class.) And last, and certainly least, the Jews themselves would surely appreciate this highly civilized manner of being booted out of their own country.

The unmistakable message of the November Pogrom had sunk in for a majority of Germany’s Jews, and they began a determined scramble to flee. In 1938, the number of Jewish émigrés from Germany numbered about thirty-five thousand. During the following year, that figure nearly doubled, to sixty-eight thousand. In the days and weeks following Kristallnacht, lines were long outside foreign embassies and consulates in all major German cities, as Jews waited to obtain the necessary papers to apply for visas. While every German Jew felt the pressure to leave, some were under more immediate duress than others.

After nearly a month of unspeakably harsh treatment in Sachsenhausen, Alex Goldschmidt was released on December 7, 1938, and informed in no uncertain terms that he had six months to leave the country of his birth or face a second arrest. So my grandfather shakily returned home to Oldenburg and, after spending a week or so recovering from his ordeal and talking matters over with his family, he took the train to Bremen and visited the Cuban consulate. There he applied for permission to emigrate to Cuba in the spring, filling out an application for himself and one for his son Helmut. They planned to establish residency in the New World and to send for the rest of the family a few months later. It must have seemed an eminently logical and sound strategy.

Cuba was among the few places on earth that even considered taking in Jewish refugees during the months following the November Pogrom. In July 1938, delegates from Cuba and thirty other countries gathered in France for the Evian Conference, to discuss what to do about the increasing number of Jews who wanted out of Nazi Germany. Once both the United States and the United Kingdom made it clear that they had no intention of increasing their quota of immigrants from Germany and Austria, the Evian Conference adjourned with most of the countries following the lead of its major players. The conference was ultimately considered a tragic failure, with Chaim Weizman, the future first president of Israel, declaring that “the world now seemed to be divided into two parts: those places where the Jews could not live and those where they could not enter.” Cuba, at least, presented itself as a theoretical haven, and Alex, his determination still intact despite his weeks in Sachsenhausen, saw the island nation as a practical solution to his family’s latest challenge.

Over the next several months, the Goldschmidt family did all it could to conserve its resources, as Alex knew that many fees, both legal and extralegal, would accompany the emigration process. Now that his business had been officially liquidated, he had no steady source of income. So on December 28, Alex moved his family from the apartment on Ofenerstrasse to a smaller, less expensive apartment on Nordstrasse, just a few blocks from the railroad station.

Alex, Toni, Eva, and Helmut spent the next few months nervously waiting for news from the Cuban consulate in Bremen. Finally, in early March 1939, the family learned that Cuba had granted visas for Alex and Helmut. But the next day, a letter arrived from Manuel Benitez Gonzalez, the director-general of Cuba’s Office of Immigration, informing them that Alex and Helmut would each have to purchase a special landing certificate if they intended to disembark in Havana. The price for each certificate was 450 Reichsmarks, a small fortune given the ever more Spartan circumstances of the Goldschmidt family.

Alex realized that they would have to tighten their belts yet again before the journey west. So on March 21, they moved to an even smaller apartment at 17 Staulinie. They were now only a block from the train station, close enough that the constant chug and chuff of engines caused their walls to shiver.A month later, the so-called Benitez certificates arrived. Alex placed the precious documents along with the visas into a cardboard folder, which he stored under his mattress. He checked their safety every night and every morning and several times during the day; other than his wedding ring, he owned nothing of greater value than those four pieces of paper.

The time had now come to secure passage to Cuba. He purchased two tourist class tickets for the May 13 voyage of the St. Louis, at a price of 600 Reichmarks (about $240) each. Alex was also obliged to pay an additional 460 Reichsmarks (about $185) for what the Hamburg-America Line termed a “customary contingency fee.” This additional expense covered a return voyage to Germany should what HAPAG called “circumstances beyond our control” arise. The line insisted that this “contingency fee” was fully refundable, should the journey proceed as planned.

Alex returned to Oldenburg in triumph, bearing his precious purchases. They had been extremely expensive, but now he had everything he needed—visas, landing certificates, tickets—to apply for a passport. On Monday, May 1, he and Helmut visited the Oldenburg offices of the Emigration Advisory Board to fill out individual applications for the “issuance of a single-family passport for domestic and foreign use.”

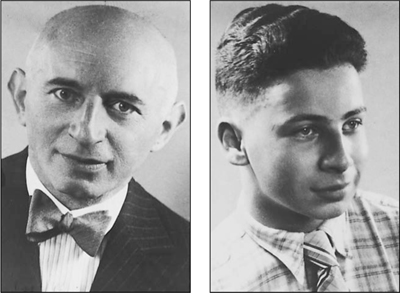

The photos taken of Alex and Helmut that they used for the passports that enabled them to board the St. Louis. These were also the photos that, attached to the space above our rear-view mirror, accompanied us on our journey.

Father and son completed their forms in much the same manner. On the line marked “profession,” Alex wrote “salesman” and Helmut “student.” Thanks to this application, I know that my grandfather’s eyes were gray and my uncle’s were blue. On the line marked destination, they both wrote “Cuba.” Both practiced the same small deception: under their address, which they listed as 17 Staulinie, there was a line requesting any previous addresses within the last year. Although the family had in fact moved twice in the past twelve months, they declared that they had lived on Staulinie “for years.” Perhaps Alex thought that a history of frequent moves might indicate a troublesome lack of stability. Whatever the reason, their white lie seems to have passed unnoticed.

Under their signatures—both of which included the repulsive required “Israel”—appeared the official assurance that “the applicant is not listed in the register of banned permits” and two questions posed by the Gestapo: “Is it assumed that the applicant wants to use the permit to avoid prosecution or execution?” and “Is it assumed that the permit to travel would endanger the internal or external security or other demands of the Reich?” To each question, on each application, an official wrote, “Nein!”

One week later, their applications were approved and their passports issued. The passports cost three Reichsmarks each and were valid from May 9, 1939, to May 9, 1940. With the St. Louis scheduled to depart the following week, the family’s flight to freedom was about to begin.

Meanwhile, about 450 kilometers southeast of Oldenburg, another family was also preparing to escape from Germany aboard the St. Louis. Joseph Karliner owned a general store, which sold groceries, hardware, and fertilizer, in a small town in Silesia, near the German-Polish border. On the night of the November Pogrom, his store was ransacked, and the next morning he was arrested and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp near the German city of Weimar. Like Alex Goldschmidt, Joseph Karliner was held prisoner for about three weeks and was released on condition that he leave Germany within six months. He, his wife, and their four children initially purchased permits to emigrate to Shanghai, China. But when they learned that the Cuban consulate in Hamburg was selling visas and landing certificates for emigration to Cuba, the Karliners sought refuge in the Caribbean nation instead, hoping it would be a stepping-stone to the United States. They followed much the same procedure as had Alex and Helmut, and by early May 1939, the Karliners set off for Hamburg and the luxury liner St. Louis.

The ship was being readied for her voyage to Havana inside shed 76 on the Hamburg waterfront, where she had lain at anchor since her most recent return from New York City. Her captain was Gustav Schroeder, known as “the smallest officer in the German merchant navy”; he stood only five feet, four inches tall. Captain Schroeder may have been short but, at age fifty-three, he was also in superb shape, the result of a twenty-minute regimen of calisthenics every day. He was apparently a real German in his personal habits, bringing to his command the traits of punctuality, order, and precision, as well as a courtliness of manner suggesting an earlier era. Captain Schroeder had thirty-seven years at sea behind him, but in May 1939, he had spent a mere four months at the helm of the St. Louis. He was also, despite six years of recruitment efforts by Germany’s ruling party, a fervent anti-Nazi.

The courtly and courageous Gustav Schroeder, captain of the SS St. Louis beginning in February 1939.

(Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Captain Schroeder was well aware of the dangers associated with his refusal to join the National Socialists. His predecessor, Captain Friedrich Buch, who had commanded the St. Louis since her maiden voyage ten years earlier, had also resisted becoming a party member. Then, in February 1939, Captain Buch was suddenly and summarily dismissed from the bridge at the end of a return voyage to Hamburg, hustled off the ship by agents of the Gestapo, the secret police, and delivered to an unknown fate. Nevertheless, Captain Schroeder was determined to maintain his independence. He politely but firmly declined even to wear an official Nazi lapel pin.

He was unable to ignore the facts, however, that among his crew of 231 were 6 firemen who were in reality undercover Gestapo agents, and that his second-class steward, Otto Schiendick, was a Nazi provocateur connected to the Abwehr, or German military intelligence. When Claus-Gottfried Holthusen informed Captain Schroeder of the unusual circumstances of the upcoming voyage to Cuba, the captain realized that the comfort of his passengers could be severely compromised by the political sympathies of his steward and the so-called firemen. He summoned his crew to a stateroom of the St. Louis and told them in no uncertain terms that they would, in ten days’ time, be expected to serve a full complement of Jewish passengers. He concluded with a stern admonition that any crew member who could not promise to perform his job with professionalism should promptly resign his commission. Neither Schiendick nor the firemen uttered a word.

Over those next ten days, and under the watchful eye of Gustav Schroeder, the crew of the St. Louis stocked the ship with all the luxuries of first-class ocean travel: caviar; salmon, both smoked and fresh; the finest cuts of meat; hundreds of cases of robust German beer and mellow Rhine wine; even the highest-quality toilet paper. Often, Captain Schroeder and his purser, Ferdinand Mueller, ignored orders from HAPAG headquarters to substitute cheaper meats or to remove fine cameras from the ship’s shop and expensive cosmetics from the hairdressing salon. The captain had decided that since the refugees had paid full fare, they deserved no less than any other St. Louis passengers had enjoyed.

The refugees had been purchasing tickets on a first-come, first-served basis since the voyage to Havana had been announced in mid-April. The last of the tickets was sold on Sunday, May 7; the ship was fully booked, all cabins and berths accounted for. By Friday, May 12, more than nine hundred refugees had begun streaming into Hamburg, making their way to the pier below the Landungsbrücken. The city was in the midst of a jubilant observance of its 750th birthday, and the brightly colored bunting and ornate Japanese-style lanterns hanging from streetlights provided a festive appearance. Yet Hamburg’s streets were also lined with red-and-black swastika flags, and the banners flew from the masts of nearly every ship in the harbor, the St. Louis included.

That afternoon, several dozen passengers made the slow walk up the gangways to board the St. Louis. They were Orthodox Jews who were following the Sabbath requirement that no journey can commence between sundown on Friday and dusk on Saturday. Given the extraordinary nature of this voyage, HAPAG officials had waived all usual boarding procedures.

On the following day, May 13, the rest of the passengers, including Alex and Helmut and the four Karliners, passed through shed 76 and made their way on board. It was a cold, raw, rainy day, which must have exacerbated the refugees’ feelings that, no matter the ugliness and terror of the previous months and years, today they were leaving their homeland under forced circumstances, very possibly never to return. My father, who traveled from Berlin that day to say goodbye, recalled that the gloomy weather seemed an appropriate backdrop to his feelings of foreboding. Herbert Karliner, Joseph’s younger son, remembers that he and his siblings were tremendously excited at the prospect of an ocean voyage, but his parents and the other adults on board were clearly saddened and subdued. HAPAG officials and Captain Schroeder, however, were doing everything in their powers to make their passengers feel welcome and to allay their fears. The crew politely assisted the passengers with their luggage, graciously ushered them to their cabins, and made them feel at home aboard the ship. This was the first time in years that Alex, Helmut, and the other refugees had been treated with respect by German officialdom. There was a momentary break in the courtesy when Steward Schiendick and his fireman gathered around the piano in the nightclub on B Deck and began singing a boisterous medley of Nazi songs, but Captain Schroeder put a stop to it immediately and sternly warned the miscreants against any further troublemaking.

Down on the pier, under a makeshift tent that had been hastily erected against the rain, a band organized by the Hamburg-America Line played through its repertory of popular tunes to serenade the departing refugees. As the afternoon advanced, the musicians performed such favorites as “Vienna, City of My Dreams,” “Muss I Denn”—a traditional German melody that twenty years later became a number-one hit for Elvis Presley as “Wooden Heart”—and several of the Hungarian Dances by Hamburg’s most famous musical son, Johannes Brahms.

But as evening descended, the refugees’ gloom deepened, and ersatz jollity soon gave way to the finality of farewell. At precisely 7:30 p.m., the ship’s horn uttered three mighty blasts, the gangways were hauled up, and the hawsers were loosed from the pilings. Slowly, ever so slowly, the St. Louis edged away from the pier into the River Elbe and toward the North Sea.

My father stood on the dock, surrounded by other solemn well-wishers, first waving to Alex and Helmut as they leaned over the railing toward him, and then merely watching as the ship grew smaller, his father and brother sailing away into the fog. As an old man, he wrote down his memories of those moments: “I felt somehow that I would never see them again. Even now, so many years later, there are times when I hear the eerie, moaning sound of the ship’s horn, when I see the disappearing boat before my eyes, getting more and more enshrouded by clouds and rain, engulfed by an uncharted future.”

TUESDAY, MAY 17, 2011. It is probably high time to come in out of the rain. The low clouds, insistent winds, and steady showers cast a spell reminiscent of that May evening so long ago, but try as I might, I cannot even remotely recreate in my mind what it must have been like for the refugees on board the St. Louis as it pulled away from this pier or for those, like my father, left standing on this very spot as they cheerfully waved and silently wished the voyagers well. So with a last long look at the iron waters of the Elbe, we trudge back over the landing bridge to St. Pauli Hafenstrasse, the main boulevard that parallels the river.

It is still only mid-afternoon, and before we return to the Hauptbahnhof for our journey back to Oldenburg, we set out on two musical pilgrimages. We first walk north along the Helgoländer Allee for a quarter-mile or so until we reach one of the most notorious avenues in all Germany, the Reeperbahn. For centuries, as long as Hamburg has been a world port, sailors, salesmen, and other roustabouts have stumbled up from the waterfront to join the lascivious parade of lusts and self-indulgence for which this thoroughfare and its side streets are known. Sex shops and honky-tonks, clip joints and night clubs, arcades and saloons and shadowy, nameless interiors promising every pleasure under the sun and moon operate twenty-four hours a day, lit by lurid neon at night and, on this gloomy day, by the gray sky and the eager, furtive desires of the passersby. In the midst of this hormone-fueled atmosphere, the Beatles found their identities and grew into master musicians between 1960 and 1962.

We walk about six blocks west along the Reeperbahn until we come to the corner of a cross street called Grosse Freiheit (“Great Freedom”) and a monument known as the Beatles Platz. Metal statues of all five Beatles (their first bassist, Stuart Sutcliffe, played with them in Hamburg) surround a circular plaza made of black concrete to resemble a spinning phonograph record. We pay our solemn, devoted respects and then walk up Grosse Freiheit to the Indra, the night club where the Beatles first performed in Hamburg as teenagers newly liberated from Liverpool.

As I gaze at the Indra’s elephant logo and try to imagine walking inside fifty years ago to hear the still-ragged yet already brilliant sound the Beatles developed in this manic laboratory, I reflect on the rightness of paying homage to this music in this place. Like millions of my generation, I was thrilled, moved, and electrified when I first heard the Beatles, on radio station KXOK in my hometown of St. Louis. Like so many of my contemporaries, I think I was initially attracted to the band’s youthful, vibrant sound at least in part because they were a joyful antidote to the grief that had descended on America when its vibrant young president was assassinated just seventy-six days before the Beatles made their stunning debut on the Ed Sullivan Show.

Then I take the next step and realize another, more personal reason that I’d fallen in love with the Beatles: they made me happy. That was no small thing, growing up as I did in a family that lived steeped in sorrow every day, a sadness that could be traced in large measure to the tragic voyage that began right here in Hamburg. What a joyful relief it had been for my eleven- and twelve-year-old self to retreat to my room and listen to those revelatory songs of love and hope. My parents had their unhappy memories and their own music. The Beatles were mine. As we begin to retrace our steps, we walk through the Beatles Platz and I lay my hand on the statues of John and Paul and whisper, “Thank you.”

I was aware of a gulf between my music and my parents’ music in my youth, but that gap began to close as I grew older and came to love what Bach and Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, Tchaikovsky and Mahler and Debussy had left for me to discover. One master I didn’t take to right away, however, was Johannes Brahms, who was born here in Hamburg in 1833. I once told my mother that I couldn’t figure out why everyone made such a fuss over Brahms. She paused a moment and then said to me, “You will. Wait till you’re forty-five or fifty. Then you’ll understand.”

She was right, more than right. There’s an underlying melancholy in nearly every note Brahms wrote that may only speak to us once we comprehend the transitory nature of all things, an understanding and appreciation of life that only a certain number of years on this earth can provide.

The Beatles still thrill me, still please me with their vibrant sounds of youthful exuberance. Brahms reassures me in the manner of a wise and kind companion who is equally comfortable in the presence of fleeting joys and immutable sorrow. I feel deeply fortunate that, as I continue this journey in Alex and Helmut’s footsteps, I can turn to all of them.

Brahms was born no more than a mile or so east of here. We retrace our steps along the Reeperbahn, under skies that are still gray but no longer rainy. Leaving the St. Pauli district, we turn right on Budapest Strasse and left along the leafy Holstenwall, walking on for several blocks until we come to the Johannes Brahms Platz, an empty, rather soulless expanse of pavement. Around the corner, we find a monument to Brahms on the approximate site where his birthplace stood until it was destroyed in an Allied bombing campaign in 1943. Amy takes my picture as I pose beside the monument and I hum to myself the solemn opening lines of the “All flesh is grass” movement from his magnificent German Requiem.

A few steps away, on Peterstrasse, we find the Brahms Museum. The docent on duty on this quiet Tuesday afternoon shares her memories of days long gone on the waterfront, when dredgers scooped up sand from the bottom of the Elbe to aid in the river’s navigation, making a high-pitched squealing sound as they worked. “How Brahms would have hated that,” I observe, and she laughs.

Brahms endured a love-hate relationship with this city all his life. As a young boy, he played the piano in some of the roughest bars in St. Pauli and was subjected to unwanted attention from the prostitutes and their customers, experiences that, he later claimed, scarred him for life and made a loving relationship with a woman impossible. Brahms hoped for years that the Hamburg Philharmonic would hire him to be its music director, but despite his many accomplishments and honored status, the orchestra never did. For that reason, Brahms insisted, he lived the life of a vagabond and never found true happiness. Yet his music touched the hearts of listeners the world over, and when he died in 1897, alone in his cramped apartment in Vienna, the flags on all the ships in Hamburg harbor flew at half mast.

As we head back to the Landungsbrücken U-Bahn station, I catch a final glimpse of that harbor and think again of the departure of the St. Louis and how Alex and Helmut must have felt on that dreary day. Despite all they had endured, they must have felt some measure of hope knowing that the voyage that would deliver them and their family to a better world was finally underway.

Forty minutes later, we are sitting comfortably in our seats on the train returning us to Oldenburg. It’s warm and dry and, nestled on Amy’s shoulder and rocked by the rhythm of the rails, I fall into a peaceful doze. But, despite myself, my thoughts are with the voyagers out on the ocean, and I recall some rueful words from Brahms’ beautiful Schicksalslied, or Song of Destiny: “It is our lot to find rest nowhere.”