MONDAY, MAY 23, 2011. After the deep emotions of the past week, today we need do nothing more strenuous, either physically or emotionally, than being tourists in the sunny French countryside. Our hosts in Montauban are wrapping up a holiday in the Pyrenees today and will welcome us to their home tomorrow. So until tomorrow afternoon, we are free to follow the call of the open road.

We wish a warm farewell to the staff of The Inn of the Twelve Apostles and are on that inviting road by 8 a.m. Had I known then what I would later learn, I would have taken the country road to Neufchâteau and Sionne, but instead we choose to spend a few hours on the limited-access A31 speeding south. The highway takes us around Dijon, birthplace of the great eighteenth-century composer Jean Philippe Rameau and the city that lends its name to a famous condiment (though we are surprised to learn that nearly all of the mustard seed used for Dijon mustard is imported from Canada). We leave the expressway a few miles north of Lyon, preferring to see the land up close from a series of D roads as we travel west and south. We cross the Loire, the longest river in France, and pass vineyards, orchards of apple and cherry trees, and fields of artichokes and asparagus. The land becomes hilly and we frequently notice the remains of ruined castles from antiquity and restored tenth-century châteaux commanding the surrounding landscape from the tops of hills.

As lunchtime approaches, we drive into the ninth-century hill town of Montbrison, birthplace of the conductor and composer Pierre Boulez. Maestro Boulez was my mother’s boss for several seasons, when he conducted the Cleveland Orchestra in the early 1970s. As we search the narrow streets of Montbrison for a fromagerie, I regale Amy with Boulez stories: of how the orchestra members made fun of his devotion to contemporary music and his disdain for Romantic composers by calling him “The 20th Century Limited”; of his brilliant recording of Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” a performance so enthralling that it was chosen by the Soviet government to represent Russian art at the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka; and of how M. Boulez once chatted very amiably and without a hint of condescension with my brother and me at an after-concert party when we were both still in our teens.

Our hunt for fromage is successful and we leave the town with an aromatic cylindrical block of its signature blue cheese, Fourme de Montbrison, a cheese that has been manufactured in the region for centuries and has earned the coveted certification known as Appellation d’origine contrôlée, or AOC. Signifying that a cheese or wine possesses certain distinct qualities, has been produced for many years in a traditional manner, or enjoys an uncommon reputation because of its geographical origin, the mark of the AOC is highly prized, particularly in this land of so many arrogant affineurs. General Charles de Gaulle once famously alluded to the fractious nature of France by asking, “How can one possibly govern a country that has 246 varieties of cheese?”

But if balky governance is the price to pay for such a luscious repast, we tell ourselves, it may well be worth it. We lunch in a lush green field spotted with bright yellow daisies, surrounded by cloud-topped hills. We are in the Auvergne, a sparsely populated region of forests, streams, and extinct volcanoes, where the ancient language of Occitan is still spoken and was brought to music lovers worldwide by Joseph Cantaloube in his hauntingly beautiful “Songs of the Auvergne.” The sun is bright and warm, the bread and cheese delectable, and once more it is hard to remember the pain that has brought us to this splendid setting.

In late afternoon, we reach the charming village of Saint-Nectaire, named after St. Nectarius, who came from Rome in the fourth century to bring Christianity to ancient Gaul. Nectarius discovered a temple dedicated to the god Apollo and forcibly reorganized it into a Christian church that still stands guard over the village as the Basilica of Notre Dame. For his trouble, Nectarius was surprised in his sleep and run through by a devout Apollinian, which hastened Nectarius’s elevation to sainthood. Today, St. Nectaire is renowned for yet another local artisan cheese, which also proudly bears the stamp of the AOC. It is my favorite cheese of the entire journey, and we purchase several wedges, some for tomorrow’s lunch and the remainder as gifts for our hosts in Montauban.

In the lengthening shadows of the oncoming evening, we follow the winding road higher and higher into the range of mountains known as Les Puys until the road straightens, the trees fall back, and we find ourselves on the banks of a glittering lake that reflects the image of the mountains beyond. We have reached our destination for the night, a village called Chambon-sur-Lac, with a population of about 350 souls. At the aptly named (for once) Hotel Bellevue, we are given a small room with an immense breathtaking view over the lake. We dine on local fowl, vegetables, and salad, a meal concluded with the flourish of yet another example of delicious fermented curd, which sends us up to bed repeating the wisdom of Monty Python: “Blessed are the Cheesemakers!”

In the clear, crisp air of morning, we continue on our way as the road rises above the timberline to an altitude over eight thousand feet. The shaggy coats of the cattle and sheep that graze here are designed for cold temperatures. For the first time on our journey, we are obliged to engage the Meriva’s heater. At the top of the pass, we climb out of the car and shiver both from the cold and in exaltation at the glorious view of craggy volcanic rocks and alpine fields and, in the shimmering distance, what seems to be the whole of southern France stretching invitingly before us. But even as I revel in the natural beauty all around me, I once more consider what has brought me here and how much our happy jaunt differs from Alex and Helmut’s journey to the south of France in 1940.

For a minute or two, I am seized by a mad impulse to stay up here with the sheep and the bracing mountain air and to forsake this nonsense of following in my relatives’ footprints. I could remain above the trees and live on cheese, I tell myself, until it’s time to fly back home. Enjoy myself on high and leave the sadness down below. But even as I tempt myself, I realize it’s all for naught; my journey may indeed be folly, but I have come here with a job to do. So with a last look at the indistinct panorama stretching away to the horizon, we climb back into the car and begin winding our switchback way to sea level, out of the pure incorruptible atmosphere of the mountains and down to the scene of the crime.

Once we return to the flatlands, we again follow express highways, which speed us west and south. We continue to see the sweet green highlands of the Auvergne on our left for miles, but by mid-afternoon we notice a profound change in the landscape. The basic color of the countryside is no longer green but a tan-to-russet shade of brown. The broad trees of farther north have given way to scrubby growth reminiscent of the American Southwest. The sun flares down relentlessly as we leave the expressway at the outskirts of Montauban and follow detailed directions to the home of our hosts, Jean-Claude and Monique Drouilhet. Their two-story house is topped with terra-cotta tiles, giving it a distinctive Mediterranean appearance. Their garden contains a number of subtropical flowers and cactus plants that thrive in hot, dry conditions. With a start, we realize that we have arrived in that storied part of the world known as the South of France.

Jean-Claude and Monique come out to greet us and we embrace warmly. He is a man of middle height, with a full head of gray hair and a ready smile under sparkling eyes. She has an exotic dark complexion and seems just a bit restrained next to her buoyantly enthusiastic husband.

Jean-Claude was born in 1934. At seventeen, he entered the teachers’ training college in Montauban with the intention of becoming an elementary and middle school teacher. He graduated four years later and then spent the next two years teaching middle school and studying agronomy at the University of Toulouse, about thirty miles to the south. In January 1958, he was drafted and sent to fight in Algeria as part of France’s nearly eight-year war to deny Algerians their independence. Jean-Claude served more than two years in the war, attaining the rank of sergeant, before returning to Montauban, where he taught middle school biology and geology and established a school radio station that was entirely staffed by students.

In the midst of his tour of duty in Algeria, Jean-Claude had obtained a leave to marry Monique. She was born in 1937, the daughter of a French army officer who spent much of World War II fighting General Rommel’s army in North Africa, leaving his wife and Monique and her three siblings alone for the duration. After the war, Monique stayed with a godmother in Normandy, where food was more plentiful, before returning to Montauban to take and pass the civil service exam. She joined the city’s Administration for Public Finances and served as the chief controller of taxes.

When Amy and I enter their comfortable home, we immediately notice the many examples of Native American art and crafts that Jean-Claude and Monique have collected: paintings, sculptures, blankets, and dreamcatchers are everywhere. When we are all seated in the bright living room with glasses of wine, the windows thrown open to welcome the late afternoon breeze, Amy, who grew up in the West, asks Jean-Claude about his obvious interest in Indian heritage. He smiles and says, “I believe it is an article of faith for many Native Americans that everything is connected. And I think my love of American Indian art and your presence in our house today are both undeniably connected to what happened here in Montauban 181 years ago.” He leans forward in his chair and weaves for us an amazing tale.

When the earliest French settlers journeyed to the New World in search of furs and fish, they established alliances with many Native American tribes. Among their closest allies and trading partners were the Osage, whose territory included parts of present-day Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. The painter George Catlin, who captured the likenesses of many Native Americans, described the Osage as “the tallest race of men in North America, either red or white; there being indeed few of the men at their full growth being less than six feet in stature, and very many of them six-and-a-half, and others seven feet.”

By the early eighteenth century, so deep a measure of trust had been established between the French and the People of the Middle Waters, as the Osage referred to themselves, that a French explorer named Étienne de Veniard invited a delegation of chiefs to Paris. There they were presented at court, took in the splendors of Versailles, went hunting with King Louis XV in the royal forest preserve of Fontainebleau, and attended an opera conducted by André Campra. Upon their return to their homeland, the Osage chiefs regaled their people with the splendors they had seen. The grandson of one of the chiefs, a young man named Kishagashugah, was so dazzled by what he had heard that he vowed, “I also will visit France, if the Master of Life permits me to become a man.”

Many years later, in 1827, having indeed grown to sturdy manhood, Kishagashugah decided to fulfill his vow. He gathered eleven of his fellow People of the Middle Waters and many furs, which he knew were highly prized in Europe, to present as gifts to the current king of France. The twelve outfitted a raft to take them down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where they would board an oceangoing vessel for the Atlantic crossing. All went well until they ran into a thunderstorm just north of St. Louis. Their raft capsized, their rich store of furs sank to the bottom of the river, and they only just managed to escape to shore with their lives.

Bedraggled and dispirited, their well laid plans thwarted, Kishagashugah and his followers fell into the clutches of a sharper and charlatan named David DeLaunay, a French-born resident of St. Louis who ran a sawmill and a boardinghouse but now saw an opportunity to make some real money as an impresario. He convinced the Osage that he was the right man, with all the right connections, to introduce them to the crowned heads of France. Six of the tribe smelled a rat and decided to return to the Middle Waters, but Kishagashugah and five of his companions joined DeLaunay aboard the steamship Commerce and made their way down the Mississippi to New Orleans. From there, they sailed upon the good ship New England and landed at Le Havre, France, on July 27, 1827.

Pandemonium greeted their arrival. DeLaunay had sent word ahead that he was bringing with him real-life savages from the New World, and by the time the New England dropped anchor in the harbor, a large percentage of Le Havre’s population was swarming over the docks, hoping to catch a glimpse of them. Protected from the curious cheering crowd by a phalanx of soldiers, the Osage rode by carriage to the city’s finest hotel, where they were wined and dined for ten days. The Indians attended the theater and made a few other well-choreographed appearances, spectacles open to anyone willing to pay DeLaunay a handsome fee for the privilege of gawking at them. Though all the money went to DeLaunay, the Osage profited in other respects. One young warrior reported later that while in France, he had been “married many times.” On August 7, they embarked via steamboat for Rouen, where the crowds, once more primed by DeLaunay’s publicity apparatus, had been waiting for four days.

On August 13, the caravan reached Paris. On August 21, at 11:00 a.m., Kishagashugah and his colleagues were afforded the honor of an audience with King Charles X at the beautiful royal palace of Saint Cloud, which overlooked the Seine a few miles west of Paris. His Majesty declared that he was very pleased to welcome his visitors, reminding them that the Osage had always been faithful allies of the French in the New World. The queen proudly introduced the royal children. There was music and food in abundance. Then Kishagashugah, his face painted the Osage tribal colors, red and blue, holding before him a ceremonial staff ornamented with feathers and ribbons, said to the king, “My great Father, in my youth I heard my grandfather speak of the French nation, and I formed then the purpose of visiting this nation when I should become grown. I have become a man, and I have accomplished my desire. I am today with my companions among the French people whom we love so much, and I have the great happiness to be in the presence of the King. We salute France!”

The encounter between these two separate worlds made news in both France and the United States, as newspapers documented the Indians’ every move. The correspondent for the Missouri Republican wrote, “The six Osage Indians, who lately arrived in France, make a considerable figure in Paris. They have been introduced at Court, caressed at diplomatic dinners, admired at the grand opera, and in short distinguished as the social lions of the day. Messieurs les Sauvages eclipse Milords Anglais.”

His great ambition realized, Kishagashugah was now amply ready to return to the Land of the Middle Waters. But he had not fully understood the terms of his agreement with David DeLaunay, who now informed him that he had arranged many more engagements throughout France, opportunities for ticket-buying citizens to gaze at the exotic visitors from across the ocean, all the while further lining DeLaunay’s pockets. So instead of going home, the Osage began wandering across France, displaying themselves to crowds that, as the novelty wore off, became smaller and smaller. After many months of this itinerant life, DeLaunay was arrested and thrown into prison on charges of fraud. Their protector and translator now taken from them, the Indians found themselves on their own, strangers in a very strange land.

They tried for a while to continue their pocket Wild West Show and managed to book themselves appearances in Italy and Switzerland, in addition to their remaining dates in France. When the tour ended, three years after their arrival in France, they found themselves destitute and alone more than five thousand miles from Osage Country, with no means to get home. Fortunately, word of their situation reached the sympathetic ears of Louis William Valentine Dubourg, the bishop of Montauban. Bishop Dubourg had done missionary work among the Osage years earlier and had lived near their ancestral homeland when he was the first bishop of St. Louis, Missouri, and the founder of what later became St. Louis University. Now hearing of the sad plight of these Osage, the bishop sent for Kishagashugah and his fellows.

So it was that in the spring of 1830, those six Native Americans, who had arrived in France with such fanfare and were now nearly starving, slowly crossed the fourteenth-century bridge over the River Tarn and presented themselves at the gates of the Montauban Cathedral. A curious crowd gathered as the bishop called for food and drink for the Indians and solicited funds to finance their return to America. In late April, the necessary money raised, the six Osage sailed for home. Two of them died during the crossing, but Kishagashugah survived to complete his long-dreamed-of pilgrimage.

That is not the end of the story, however. In the late 1980s, while still teaching natural sciences at the middle school, Jean-Claude came across a reference to Montauban’s Osage connection. Intrigued, he researched the descendents of Kishagashugah and discovered that the tribal government of the modern Osage Nation is headquartered in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, the county seat of Osage County. He wrote to the mayor of Pawhuska, suggesting that after all these years, the People of the Middle Waters and the citizens of Montauban should renew their acquaintance. Thus was born the sister-city relationship between Montauban and Pawhuska—the relationship that led me to Jean-Claude and his kind assistance and hospitality.

“So you see,” says Jean-Claude with a smile, “because Kishagashugah came to Montauban to honor his vow to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather, you have come to Montauban . . . to follow in the footsteps of your grandfather.” I look away, my eyes suddenly full of tears.

“I think the native peoples of your country are quite right,” continues Jean-Claude, his voice a bit huskier than before. “Everything is connected.”

ONCE UPON A TIME, many years ago, there was a colorful country of wide plains and towering peaks, inhabited by noble swordsmen and gentle damsels, husbandmen and troubadours, shepherds and poets, a land that went by the name of Occitania. Its borders encompassed most of what is now southern France, as well as parts of Italy and Spain and the principality of Monaco. It had its own flag, which featured a distinctive twelve-pointed star, and its own unique language, known as Occitan, which appeared for the first time in written form in the tenth century but had existed as a spoken language for at least two hundred years before that. During the early Middle Ages, in the time of Charlemagne and the Visigoths, Occitania was politically united, but eventually the country came under attack by the kings of France and gradually lost its independence. One of the turning points in Occitania’s attempt to remain a self-governing entity came in 1621, when a poorly armed but determined gang of Occitan fighters barricaded themselves in the church of St. Jacques and held off a regiment of King Louis XIII’s army for three months before surrendering. Over the next three centuries, the language and some of the customs of Occitania began to fade from the world’s awareness. But in the past hundred years or so, its distinctive voice has been heard again, as Occitan is now taught in public schools. In no other place has that revival been more vibrant than the site of that three-month siege of 1621: the city of Montauban.

Not everyone in Montauban shares a gauzy, fairy-tale view of Occitania. In most respects, the city’s sensibilities are firmly rooted in the present day. It is the capital of the departement of Tarn-et-Garonne, with all the administrative concerns that accompany such a designation. The metropolitan area of Montauban is home to more than a hundred thousand people; two of the principle industries are agriculture and the manufacture of cloth and straw hats. The city is an important hub in the extensive railway system of France, with high-speed trains departing for Paris, Nice, and Bordeaux several times a day from its grand nineteenth-century station, the Gare de Montauban-Ville-Bourbon. On weekend afternoons, enthusiastic fans jam the Stade Sapiac to cheer on US Montauban, a rugby football club. Montauban is also home to a university; a theater; a daily newspaper, Le Petit Journal; and an orchestra, Les Passions, devoted primarily to baroque music.

But the city is well aware of its past, and many citizens are quick to remind visitors that their city’s name is spelled Montalban in the Occitan language. The city’s chief architectural wonder is the bridge spanning the river Tarn. Construction of the bridge began in 1303 on orders from King Philip the Fair and was completed more than thirty years later. Nearly eight hundred years old now, it handles heavy automobile and truck traffic as nimbly as it did carriages and oxcarts during centuries past. The seventeenth-century Place Nationale, the striking town marketplace, is surrounded by pink brick houses above double rows of arcades. During the Terror of the French Revolution, those unfortunates who were about to meet their deaths at the guillotine were first brought to the Place Nationale so a bloodthirsty mob could jeer and throw vegetables at them.

Olympe de Gouges, a playwright, journalist, and early feminist, born in Montauban in 1748, was guillotined in Paris, partly because of her uncompromising stand on behalf of women’s rights. Also born in Montauban, in 1749, was André Jeanbon Saint-André, the man who suggested blue, white, and red as the colors of the French flag. Thirty-one years later, the city witnessed the birth of its most celebrated resident, the great painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. Montauban’s fine art museum, located at the eastern end of the old bridge, is named for Ingres. In 1944, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was transported from the Louvre in Paris and hidden in a vault beneath the Musée Ingres to prevent the Nazis from carrying it off.

Montauban also houses the Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation. Its holdings include a painting by G. R. Cousi depicting the infamous event of July 24, 1944, when four members of the Resistance were hanged from two graceful plane trees in a public square in Montauban. The square is known today as the Place des Martyrs. Although no major battles were fought there, Montauban certainly contributed its share of martyrs and other victims to the sorrowful history of France during the Second World War.

After France’s formal declaration of war on Germany on September 3, 1939, and the decrees relating to the internment of German citizens in France on September 14, there followed an eight-month period largely devoid of military activity, a time that came to be known as the “phony war.” That phrase, attributed to William Borah, a U.S. senator from Idaho, abruptly disappeared from common usage on May 10, 1940, when Germany launched its lightning assault upon Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. It defeated those countries within weeks, and in less than a month, German tanks had swiftly circumvented the supposedly invulnerable Maginot Line and swept into France.

When the German army stormed into Paris in the early morning hours of June 14, the troops marching exultantly down the Champs Elysées and under the Arc de Triomphe encountered a nearly deserted city. Along with thousands of its citizens, the French government had fled Paris and headed south, first to Tours and then to Bordeaux. Paul Reynaud, the prime minister of what was known as the Third Republic, turned for assistance to Marshal Henri-Philippe Pétain. The general had made his reputation as the architect of the French strategic victory at the battle of Verdun during the First World War. But Verdun later became a symbol of the folly of that “war to end all wars.” Over the course of eleven months in 1916, nearly seven hundred thousand French and German soldiers died in the effort to move the battle lines a few thousand yards in either direction. Twenty-four years later, as the Germans approached Paris, Renaud asked Pétain to serve as his vice prime minister. Then on the evening of June 16, two days after German troops had entered Paris, Renaud resigned and recommended that a new French government be created with Marshal Pétain as its prime minister. The general was eighty-four years old.

A debate ensued over how to respond to the overwhelming might of the German forces. Renaud argued for continuating French defensive efforts, moving the government to French colonies in North Africa, and relying on the French navy rather than its ravaged army. But with the countryside still in chaos, Pétain and others opted simply to surrender. Shortly after noon on June 17, Pétain took to the national airwaves and declared, “France is a wounded child. I hold her in my arms. The time has come to stop fighting.” Listening to the radio broadcast while at lunch at a bistro in the southern port city of Marseille, the French composer Darius Milhaud felt his heart break and witnessed other patrons of the restaurant weeping in despair. He wrote later, “I realized clearly that this capitulation would prepare the soil for fascism and its abominable train of monstrous persecutions.”

Five days later, on June 22, the world witnessed one of the most elaborately staged surrender dramas in its anguished annals of humiliation. Adolf Hitler himself insisted that the armistice be signed in the very same railroad car and on the very spot where, twenty-two years earlier, the Germans had surrendered at the end of World War I. Hitler had the train car removed from a museum and brought to a little clearing in the forest of Compiègne, about forty miles north of Paris. French officials signed the armistice, believing it to be a temporary document. A real and lasting peace treaty would emerge after the expected German defeat of Great Britain, which was assumed to be only a few months if not weeks away, now that nearly all of Western Europe had fallen before the might of Germany’s Blitzkrieg. But at the beginning of June, as France was falling, British forces staged a miraculous retreat from the French coastal city of Dunkirk, escaping across the English Channel to fight another day. Britain did not fall, so the provisional armistice remained on the books until the Liberation.

Under the terms of the armistice, France was divided into two main parts. The Occupied Zone—about 60 percent of the country, including its most economically robust regions, beginning north of the river Loire and then extending south to the Spanish border to include the entire Atlantic coastline—was administered by a German military governor operating from Paris. The Unoccupied Zone—south and southeastern France, about forty departements in all—was ruled by Marshal Pétain and his government, newly removed to the French city of Vichy. Ostensibly the French government administered the entire country, although the armistice acknowledged and respected “the rights of the occupying power.” Everyone was fully aware that all real power flowed from Berlin and not Vichy. Pétain was a puppet.

France was required to deliver to the German police any refugees from the Third Reich whom the government in Berlin might demand. The French negotiators objected to this provision at first, declaring it a betrayal of those who had entered their country seeking asylum from Germany. But when the Germans made it clear that they would not yield on this demand, the French surrendered once again. In the next few months, a band of Gestapo agents visited a number of internment camps in the Unoccupied Zone and made a list of about eight hundred refugees; the Vichy government duly delivered them. Among those sent back to Germany was Herschel Grynszpan, the man who Nazi officials blamed for the pogrom known as Kristallnacht, since Grynszpan’s assassination of a German diplomat in Paris in early November 1938 ostensibly triggered the campaign of violence. Once returned to Germany, Grynszpan was never seen again.

On July 1, 1940, the French government, including the members of Parliament, gathered in the town of Vichy, located in the Auvergne region of south-central France. Like Martigny-les-Bains and Contrexéville, Vichy long enjoyed a reputation as a spa town because of its thermal waters. In the 1860s, Emperor Napoleon III took the cure five times. He built lavish homes in Vichy for his mistresses and glittering casinos for his courtiers. Vichy was chosen to be the seat of the new government in part because of its relative proximity to Paris (about four hours by train) and partly, thanks to its Napoleonic legacy, because it was the city with the second-largest hotel capacity in all of France.

Within days, the world would learn of the shocking new direction in which the Vichy government would lead France. On July 10, the senators and deputies who remained from the Leon Blum–led Popular Front National Assembly of 1936 voted overwhelmingly to revoke the constitution of the Third Republic and to grant Pétain full powers to declare a new one. The vote, taken in the ornate Vichy opera house, was 569 to 80; those who voted in the negative were later lauded for their courage and celebrated as the Vichy 80.

Pétain wasted no time putting his new authority to use. Within forty-eight hours, he issued three constitutional edicts. The first one bestowed upon him the title of Chef de l’État Français, or head of the French state. The second declared that the head of state possessed a “totality of government power”—legislative, executive, judicial, diplomatic, and administrative—and was thus responsible for creating and executing all of the country’s laws. The third edict, dissolving the Senate and Chamber of Deputies indefinitely, condemned France to the authoritarian rule of one man: Marshal Pétain.

On July 12, Pétain addressed the country and declared, “A new order is commencing.” The French national motto—Liberty, Equality, Fraternity—forged in the revolutionary fires of 1789, was replaced with a slogan long espoused by right-wing groups: Fatherland, Family, Work. Democratic liberties and guarantees were immediately suspended in favor of a paternalistic, top-down system that emphasized government control of the individual and unfettered corporate power. Pétainists condemned what they called the indecency and depravity of the previous regime, with its tolerance for jazz, short skirts, and birth control, and called for the reintroduction of traditional family values to daily life. The crime of délit d’opinion, or felony of thought, became illegal, and citizens were frequently arrested for publishing, or even uttering, criticism of the regime. Former Prime Minister Paul Reynaud, who had essentially turned over control of the government to Marshal Pétain, was arrested in September 1940 and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Almost immediately, the Vichy government began a dual campaign promoting the emergence of this new “true France” and affixing blame for the country’s quick and humiliating defeat on the battlefield in the spring. At the heart of both efforts was the desire to weed out “undesirables,” those whose treachery, Pétain believed, had undermined what otherwise would have been a decisive victory against the German invader. These undesirables, long termed the Anti-France by the right wing, included Protestants, Freemasons, foreigners, Communists, and Jews.

Although additional undesirable elements of the French population, including Gypsies, left-wingers, and homosexuals, were targets of official discrimination, the campaign of anti-Semitism that began almost immediately after the establishment of the Vichy government was nothing short of an all-out assault. The French undoubtedly studied the Nazis’ Nuremburg Laws for guidance, but the flood of edicts and ordinances that began in July 1940 was not prompted by orders from Berlin. Henri du Moulin de Labarthète, who served as Marshal Pétain’s chief of staff, declared unambiguously, “Germany was not at the origin of the anti-Jewish legislation of Vichy. This legislation was, if I dare say it, spontaneous, native.” In 1947, Helmut Knochen, a German storm trooper and the director of the security police in France, recalled that “we found no difficulties with the Vichy government in implementing Jewish policy.”

The objective of the new government’s initial laws was the restriction of the rights of foreigners living in France, measures that, while affecting foreign Jews, weren’t specifically anti-Semitic. On July 13, Pétain issued an edict stating that “only men of French parentage” would be allowed to belong to the civil service. On July 22, another decree was announced, this one allowing the government to revoke the citizenship of all French men and women who had acquired their status since the passage of the liberal naturalization law of 1927. The next day saw the passage of a law that called for the annulment of citizenship and the confiscation of the property of all French nationals who had fled France after May 10, the start of the German offensive, without an officially recognized reason. This was the first measure that seemed specifically aimed at Jews, and among those singled out was Baron Robert de Rothschild, who had helped to fund the agricultural center at Martigny-les-Bains. The Vichy officials justified this new law by charging that Rothschild and his co-religionists had revealed themselves to be “Jews before they were French” by abandoning their country at the very moment it needed them most; thus, they declared, these people no longer deserved the honor of French citizenship.

Over the next ten weeks, more laws were issued in the Vichy regime’s by now undisguised attempt to solve its “Jewish problem.” On August 27, the Daladier-Marchandeau ordinance of 1939, prohibiting anti-Semitism in the press, was repealed, and several notorious Jew-baiting publishers were permitted to renew their activities in print. On August 16, the government announced that, henceforth, only members of the newly created Ordre des Médecins would be allowed to practice medicine, whether as doctors, dentists, or pharmacists. The catch was that membership in the Ordre was restricted to persons born in France of French fathers, and by now the designation “French” was in the process of being radically redefined. On September 10, a similar decree was announced that affected the practice of law. The Vichy minister of the interior, Marcel Peyrouton, declared that doctors and lawyers were under an obligation to exclude from their ranks those “elements” who by certain “acts or attitudes” had shown themselves “unworthy to exercise their profession in the manner the present situation demands.”

The definition of what constituted a “French” person and what constituted a Jew was spelled out in a decree issued on September 27. Taking its cue from the notorious 1935 Nuremberg Laws, the measure stated that anyone who had more than two grandparents “of the Jewish race” was a Jew. The law went on to declare that any Jew who had fled to the Unoccupied Zone was henceforth banned from returning to the Occupied Zone. It also called for a census of Jews in the Occupied Zone to be conducted within the coming month, required that the word Juif now be stamped on identity cards belonging to Jews, and called for yellow signs to be placed in the windows of stores owned by Jews. The signs were to carry the words, in both French and German, “Jewish Business.” Other stores, of their own volition, soon began sporting signs that read “This business is 100 percent French.”

The culmination of this legal attack on the rights and position of Jews living in France was the Statut des Juifs, or Statute on Jews, enacted by the Vichy government on October 3, 1940. The law began by reiterating that anyone with more than two Jewish grandparents would be considered a member of the Jewish “race”; from now on spouses of Jews would also be designated Jewish. But the main intent of the statute was to affirm the second-class standing of the Jews of France by specifically banning them from many positions in public life. Henceforth no Jew could be a member of the officer corps in the military or a civil servant, such as a judge, a teacher, or an administrator; no Jew could work as a journalist, a publisher, a radio broadcaster, or an actor on stage or in films; no Jew could work as a banker, a realtor, or a member of the stock exchange.

Other anti-Semitic statutes would follow in the coming months, laws that called for the confiscation of radios and telephones from Jewish homes in France, established curfews that allowed Jews to be on the public streets for only certain hours every day, and confined Jews to using only the last car in the trains of the Paris Métro.

Though the drumbeat of official anti-Semitism had been growing ever louder since the establishment of the Vichy regime in July, the cymbal crash of October 3 was a stunning blow to the Jews of France, who had certainly heard tales of Nazi atrocities from across the German border but who had never expected such measures would be enacted in their homeland. Raymond-Raoul Lambert, the CAR director who had met the St. Louis passengers at Boulogne-sur-Mer, wrote in his diary after the announcement of the Statut des Juifs, “I wept last night like a man who has been suddenly abandoned by the woman who has been the only love of his life, the only guide of his thoughts, the only inspiration of his action.” It would not be long, however, before feelings of betrayal would give way to fears of a far greater danger than a broken heart.

But where the Jews saw peril in the Statut, others saw opportunity. If one of the stated goals of the still-new government was the segregation of Jews from mainstream French society, then exceptional vigor in the pursuit of that goal could only win favor in the eyes of Vichy officials. On October 4, an addendum to the previous day’s law authorized officials throughout France to place under confinement or into conditions of forced labor any foreign-born Jews who might be living in their jurisdictions. Thus a young man from Montauban whose meteoric rise through the French bureaucracy had been propelled by tragedy saw his opening.

René Bousquet was born in Montauban in 1909, the son of a radical socialist notary. As a boy, he became fast friends with Adolphe Poult, whose father, Emile Poult, was the chief executive of a successful French confectioner. The firm, Biscuits Poult, was founded in 1883. It manufactured cakes, biscuits, wafers, tarts, and cookies of all shapes and sizes, which were consumed with relish in Montauban, site of its main factory, and throughout France. Emile Poult was thus a wealthy man, and his son Adolphe and René Bousquet spent many happy hours together at the Poult family estate.

The River Tarn, which flows through Montauban, has long been the source of the worst flooding in all Europe, with the possible exception of the Danube. In March 1930, following a winter of high snows near the river’s source in the Cevennes Mountains and exceptionally heavy spring rains at lower altitudes, the Tarn flowed deep and fast through Montauban, rising more than fifty-six feet above its normal level in just twenty-four hours. In what was subsequently termed a millennial flood, about a third of the surrounding departement was under water, thousands of houses were swept away, much of the low-lying regions of Montauban were destroyed, and more than three hundred people drowned.

Many of the town’s inhabitants helped to save the victims of the flood, including Adolphe Poult and René Bousquet, each almost twenty-one years old. The two friends saved dozens of lives in nearly thirty-two hours of continuous exertion. Then, his judgment probably compromised by exhaustion, Adolphe misstepped, fell into the raging river, and was swept away. His body was never recovered.

For what were termed his “belles actions,” Bousquet became something of a national hero, awarded both a gold medal and the Legion of Honor. He also won the undying affection and loyalty of his friend’s father, Emile, who was devastated by the loss of his son and embraced young René as his surrogate heir.

Over the next ten years, Bousquet quickly rose from one high-profile position to the next, initially boosted by his celebrity and then well served by his unerring ability to cultivate mentors. Bousquet began as the protégé of Maurice Sarraut, a socialist senator and the publisher of an influential newspaper in nearby Toulouse. In April 1938, Sarraut became minister of the interior in the government of the Popular Front and appointed his protégé to the position of sous-préfet, or ministerial representative, for a city in northern France. In 1940, shortly after the armistice, Bousquet, at age thirty-one, was serving as prefect. But Sarraut had been swept out of power with the rest of the Third Republic. In order to remain in favor with his new superiors in Vichy, Bousquet knew that he would have to do something to catch their attention.

He saw his chance in the edict of October 4, which gave prefects the authority to intern or place under house arrest any foreign-born Jews within their jurisdiction. Bousquet did some research and found that in the nearby departement of Vosges, there were sixty German Jews living in a camp in Sionne. He quickly called his counterpart in Vosges and offered to take these “undesirables” off his hands. The other man agreed, leaving Bousquet with a nice cache of refugees but with no place to house them. Bousquet asked Émile Poult, now a powerful figure in the largely right-wing French business world, if he knew of a space sufficiently commodious to house sixty Jews for a few weeks. The older man offered his dear young friend the use of his factory in Montauban. The area within the factory gates where trucks were loaded with their daily shipments of cookies and cakes was large enough for sixty cots, with extra space for exercise. The high walls that surrounded the factory would make escape unlikely and its location was highly convenient: just a few hundred yards down the street from the Montauban railway station.

Thus, on October 13, 1940, Grandfather Alex and Uncle Helmut arrived at the Gare de Montauban-Ville-Bourbon on a train from the north. They and their fifty-eight fellow undesirables were quickly marched about two blocks down the Avenue de Mayenne, turned right, and walked through the open gate of Biscuits Poult, which would serve as their address for the next four weeks.

I really have no idea how Alex and Helmut spent that month within the walls of the cookie factory. I like to think that they were allowed to walk around the lot several times a day, that they were fed generously, and that M. Poult begrudged them at least one wafer or tartelette from his vast inventory at each meal. I cannot imagine how they came to terms with being prisoners held behind secure walls after the comfort of their initial warm welcome in France. I know that on November 6, Marshal Pétain, on a tour of the Unoccupied Zone, made a stop in Montauban, where he gave a speech in the Place Nationale before a wildly cheering crowd. Perhaps Alex and Helmut could hear bits of the celebration from the open-air Poult courtyard. I know that two days later, on November 8, the prefect of the departement of Tarn-et-Garonne sent a memorandum to the chief of police of Montauban that stated, “Per our telephone conversation, I have the honor of requesting from you a patrol to accompany sixty foreign Jewish refugees to Camp Agde. Those individuals will assemble at noon in the custody of the municipal police at the Poult building. The train is due to depart for Agde at 3:30 p.m.” Indeed on the following day, November 9, 1940, two years to the day after Kristallnacht, under the watchful eyes of the police, Alex and Helmut walked back up the Avenue de Mayenne to the station and boarded a train heading south to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, as their forced odyssey through France continued.

René Bousquet, whose friendship with Emile Poult brought my relatives to Montauban, continued his rapid rise through the ranks of the Vichy regime. Less than two years later, he was made secretary-general of the national police. In that capacity, he planned and carried out the infamous roundup of more than thirteen thousand Jews on July 16 and 17, 1942. His victims were first held for five days at an enclosed bicycle track in Paris—the Vélodrome d’Hiver, or Winter Velodrome—and then shipped to various extermination camps. After the war, Bousquet was tried on charges of “compromising the interests of the national defense” and received a sentence of five years of dégradation nationale, or a ceremonial loss of rank. But that judgment was immediately lifted because Bousquet made a convincing case that, while appearing to collaborate with the Nazis, he had been secretly assisting the Resistance all along. After lying low for a while, Bousquet returned to politics and helped finance François Mitterrand’s successful campaign for president in 1981. Then, in the late 1980s, the Romanian-born Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld filed a complaint against Bousquet for crimes against humanity. After many delays a trial date was set, but before Bousquet ever saw the inside of a courtroom, he was assassinated in his own home on June 8, 1993. The gunman was reportedly a right-wing sympathizer who did not want the full story of René Bousquet to be revealed.

Bousquet’s imprisonment of the Jews at the Velodrome in Paris in July 1942 was one of the shameful preludes to the mass deportations that began the following month when the Vichy government approved transports that delivered the Jews of France to the killing centers of Germany and Poland. In late August 1942, the spiritual descendant of the bishop of Montauban, the gentle man who welcomed the Osage and helped them return to their homeland in 1830, raised his voice in protest. Pierre-Marie Théas, bishop of Montauban since 1940, wrote a pastoral letter condemning the deportations, declaring, “I give voice to the outraged protest of Christian conscience and I proclaim that all men and women, whatever their race or religion, have the right to be respected. Hence, the recent antisemitic measures are an affront to human dignity and a violation of the most sacred rights of the individual and the family.” He planned to mail his letter to his fellow priests in the surrounding parishes so that they could help amplify his protest.

But his secretary, Marie-Rose Gineste, warned the bishop that if he put his remarks in the mail, agents of the Vichy government would no doubt intercept the envelopes and destroy their contents. So she made multiple copies of his letter, which also implored parishioners to save Jews from deportation, mounted her bicycle, and over the next four days pedaled more than sixty-five miles over hilly roads through towns, villages, and hamlets to each parish in the surrounding region. On the following Sunday, August 30, Bishop Théas’s letter was read from every pulpit to packed congregations, the only exception being a church with a Vichy sympathizer as its priest. In response to the call, many French families began to shelter Jews in their homes.

Bishop Théas was arrested by the Gestapo in 1944, and sent to the concentration camp known as Stalag 122, which was located near the forest of Compiègne, the site of the French surrender. He survived the ordeal and died of natural causes in 1977 at the age of eighty-two. Marie-Rose Gineste took an active role in the Resistance, hiding Jews, forging identity cards, and leading many Jews to safe houses in the surrounding countryside. She remained in Montauban and continued to ride her sturdy little bicycle until she was eighty-nine years old. Then, in December 2000, she donated the bicycle to the Holocaust memorial at Yad Vashem in Israel. She died in the summer of 2010, aged ninety-nine.

For their efforts on behalf of humanity, Bishop Pierre-Marie Théas and Marie-Rose Gineste were both named by Yad Vashem as “Righteous Among the Nations.”

THURSDAY, MAY 26, 2011. I learn all this during two rich, full days under the hot southern sun of Montauban, in the bracing company of Jean-Claude and Monique. Wednesday begins with a tour of the town. Jean-Claude points out local landmarks. We see the bullet holes that remain in the stone walls of the church of St. Jacques, where the outnumbered Occitan irregulars were defeated in 1621. There are the slightly raised cobblestones in the Place Nationale where tumbrels paused so that townspeople might jeer and hurl vegetables at the condemned victims of the Revolution on their way to the guillotine. Next is a little stone plaque on Rue Adolphe Poult, almost invisible on an embankment by the River Tarn, heralding the bravery of the young man during the great flood of 1930. Jean-Claude also takes us to the Place des Martyrs, where the four members of the Resistance were hanged in 1944. The public square still contains the withered stump of one of the four trees.

We visit the Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, which displays posters from the Pétain era illustrating the dangers of the international Jewish conspiracy that the National Revolution was determined to defeat. In one poster, taken from an exhibition called Le Juif et la France, a bearded man with an enormous nose, his eyes popping and beads of lascivious sweat breaking out on his forehead, fondles with clawlike fingers a globe of the world. In another, a righteous French policeman holds two wriggling, shifty-eyed men by the scruffs of their necks. They, too, sport oversized noses and are both clutching bags that are presumably filled with ill-gotten money. The poster is captioned with a single word: Assez! or Enough! When I ask Jean-Claude if he recalls seeing this sort of ugly propaganda in his youth, he sighs and says, “Everywhere.”

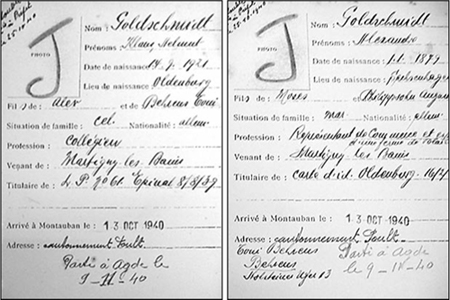

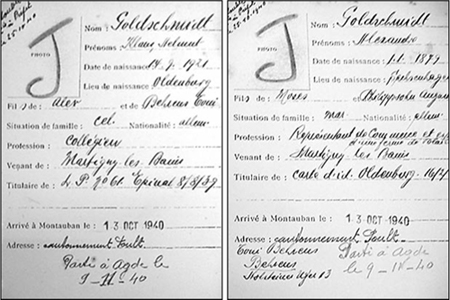

Our next stop is the Montauban city archives. There, in the police files from 1940, we find the index cards that helped me trace the movements of Grandfather Alex and Uncle Helmut. Both cards feature a red letter J in the upper-left corner, along with the assurance that the local prefect examined the cards on October 25. The cards note their arrival in Montauban on October 13 and their departure for Agde on November 9. They list Helmut’s profession as student and Alex’s as salesman and poultry farmer, revealing that my grandfather must have retained pleasant memories from his brief months in Martigny-les-Bains. Both cards indicate that Alex and Helmut’s address while in Montauban was the “Cantonnement Poult,” or the temporary quarters provided by the proprietor of the cookie factory.

Again, I experience that curious mix of excitement and sorrow that always seems to accompany any tactile evidence of my relatives’ existence. I cherish them because I possess so few items that speak to their once having lived, breathed, and walked this earth. Yet virtually everything I discover along this journey is another strand of the net that slowly but inexorably closed around them during their time in France. I hold the cards close and, when no one is looking, kiss them quickly, one after the other.

Our final destination for the day is another public square in Montauban, this one dedicated to the memory of the French soldiers who fought in the wars of the twentieth century. There are separate monuments for each of the world wars, for Algeria, and for Vietnam. The square is dominated by a twenty-two-foot statue called Hope Chained, a monument dedicated to the thousands of people deported to their deaths in Eastern Europe during the 1940s. I am humbled and honored to learn that Jean-Claude has organized a small memorial service in memory of Alex and Helmut.

From the files of the central police station of Montauban in 1940, the identity cards of Alex and Helmut. The father is listed as a salesman and a poultry farmer, the son as a student. Probably more important to the authorities, though, was the defining “J.”

About two dozen people, alerted by a notice Jean-Claude placed in the local newspaper earlier in the week, have gathered in the square as the shadows of early evening begin to lower the temperature of a blazing afternoon. Jean-Claude has asked a local florist to deliver a basket of red, yellow, and white daisies, over which is a small red banner that reads, “For my grandfather Alex and my uncle Klaus-Helmut.” He has also brought along two flags on aluminum poles. He plants them in the grass on either side of the concrete path leading to the base of the Hope monument, the site of our little ceremony. Both flags are red, white, and blue: the French Tricolour and the American Stars and Stripes. The American flag was presented to Jean-Claude by his Osage friends in Oklahoma, and it incorporates an image of End of the Trail, the doleful sculpture by James Earle Fraser, into its design. While it seems odd in this context, I reflect that it’s not so inappropriate to recall the extermination of the Native American population when mourning the evil that humans have wrought.

Shortly after 6 p.m., Jean-Claude says a few words in French, explaining what has brought Amy and me from America to join them this evening. He introduces Eugène Daumas, a member of the Tsigane, or Gypsy, population, who speaks briefly about the six thousand men, women, and children of his kind who were deported from France between 1940 and 1946. Then I hand the basket of flowers to Amy and, in halting English, tell the assembled of my conflicted feelings, of my anger at those Montaubanians of seventy-one years ago, of my bottomless gratitude to those gathered today, and of my particular gratitude to Jean-Claude and Monique for the honor and kindness they have shown my family on this memorable day. Amy and I walk to the base of Hope Chained, where we place the flowers and I whisper a few words to Alex and Helmut. The crowd slowly disperses into the warm evening. With no further words passing between us, Jean-Claude and I embrace.

On Thursday morning, we four take a drive north and east of Montauban to the village of Septfonds. Locally, the town is renowned for the seven springs for which it is named and for its production of colorful straw hats. But beyond the immediate horizon, the name Septfonds has a far more malevolent meaning, one that Jean-Claude wants to be sure we learn. About two miles outside the town limits, we come upon an immaculately kept cemetery, the final resting place for eighty-one Spanish men and boys who crossed the border into France as refugees from the bloody Spanish Civil War. At a camp set up in Septfonds more than fifteen thousand men, women, and children lived in cramped, highly unsanitary conditions from early 1939 until the beginning of 1941, when the camp became a prison for Jews and other undesirables subject to the racial laws of the Vichy regime. The peaceful Spanish cemetery is its own memorial to the ordeal of the Spanish refugees. To find any mention of what happened to the Jews of Septfonds, we must get back into the car and drive several more miles over the rolling countryside.

Fortunately, Jean-Claude knows the way, as there are no road signs. We soon come to a small, enclosed patch of field set off from the surrounding farmland by a low fence. Within is an empty replica of a barracks, modeled after the inadequate shelters provided to the thousands of Jews who survived here for months until they were shipped East. There is also a granite monument in the shape of a headstone, erected in memory of those interned and deported from here between 1939 and 1944.

It’s a cloudy day with a cool breeze, a welcome relief after yesterday’s unrelenting sun. An almost complete silence prevails, broken only by the occasional bird song or the sound of the black-and-white cows mooing in an adjacent pasture. The four of us keep the silence, my thoughts a jumble of sadness for the long-dead victims and deep appreciation for the pastoral peace of the landscape.

Next, we drive a few miles to the stunning medieval village of Saint-Antonin-Noble-Val, founded by the ancient Celts in the ninth century. We walk the narrow, winding streets, admiring old wooden doorways and stone gargoyles, the eleventh-century abbey, and a shop selling eighteenth-century clocks. In the market square, Jean-Claude shows us a centuries-old chopping block, complete with an iron sluice for the quick disposal of blood, where many generations of chickens met a sharp, quick end. Also in the square is a stone monument to the local partisans who contributed to the Resistance. I point it out to Jean-Claude who rolls his eyes, grimaces, and says emphatically, “Oh, yes . . . every village and town in France has erected a monument to their heroic Resistance fighters. With such brave people in every corner of France, how on earth did Philippe Pétain ever come to power?” It is a question for which he seems to know the answer, so I do not press him but vow to bring it up again later.

By the time we return to Montauban in the late afternoon, the warm southern sun has reappeared. At Jean-Claude’s suggestion, we cross to the western side of the Tarn and drive through thinning traffic to the Avenue de Mayenne, a bedraggled little boulevard of shuttered shops and posters advertising athletic shoes and an upcoming outdoor concert by an Algerian rapper. We leave the car at an unused market square, walk half a block, and suddenly I am staring at the walls of what served for four weeks as my grandfather and uncle’s forced domicile seven decades ago. Above graffiti-covered sheet metal gates are red lacquered panels bearing the words “Émile Poult” and “Biscuits.” Above that are arched windows of green glass bordered by red and white bricks. A block and a half up the avenue is the railroad station. Again, I call upon my imagination to help me visualize an image from the past, to recreate the scene of Alex and Helmut trudging in a line of their fellow prisoners down the street from the station in October and then retracing those steps in November. But my eyes only reveal to me the soiled pavement, empty save for a discarded water bottle and an underfed terrier trotting along the gutter, sniffing the ground as he goes. Once again, I tell myself ruefully, I am too late.

The abandoned Poult cookie factory on the Avenue de Mayenne in Montauban that served as Alex and Helmut’s forced domicile for a month in 1940.

We walk around the corner, along the Rue Ferdinard Buisson, to an alleyway that leads to the rear of the abandoned Poult factory. Once again, we are blocked by a high metal gate, but it is possible to push a section aside and glimpse the courtyard where, presumably, the prisoners slept and took what little exercise was allowed them. The concrete floor of the enclosure has been pierced by weeds; everywhere are unmistakable signs of neglect and ruin. My relatives have moved on. There is nothing to do but go home.

This evening, our last in Montauban, Jean-Claude pours us drinks on the patio of the Drouilhet home, accompanied by the family cat whom Jean-Claude insists has no name, although Monique cuddles the cat and calls it Chou-Chou, a term of endearment that literally means “cabbage cabbage.” After a dinner of chicken, pasta, and a local vintage, Jean-Claude recalls his pleasure at visiting his Osage friends in Pawhuska and breaks into a vigorous solo performance of Oklahoma, “when ze wind comes right behind ze rain!” We all join in and then warble “Tonight” from West Side Story, “Fugue for Tinhorns” from Guys and Dolls, Elvis’s “Heartbreak Hotel,” and a few more show tunes and rock ballads, leaving me to reflect, not for the first time, how successful our musical exports have been in burnishing America’s reputation around the world.

After the laughter dies down and the sun has long set, I remind Jean-Claude of his remark regarding the Resistance memorial in Saint-Antoine-Noble-Val. I observe that he’d sounded a bit cynical and wonder what he thinks of contemporary attempts to honor those who fought both the Nazi invaders and the French collaborators.

Grinning a bit sheepishly, he replies, “I hope I never sound cynical where the Resistance is concerned. I do get a little impatient when officials today pretend no one collaborated and everyone resisted. That is simply not true and no amount of whitewashing will make it true . . . any more than trying to whitewash away your history of annihilating your native people will make that truth go away.”

Jean-Claude pours himself a bit more wine and continues. “My father fought in a local Resistance group called Prosper, and so did my uncle. The Nazis captured my uncle and sent him to Buchenwald, and he never returned.” He looks at Monique and then back at me. “This is why I have been so eager to help you in your search for your relatives. Doing this research is a way for me to pay tribute to my father and my uncle and all Resistance fighters.” He pauses, takes another drink. “This is my heritage, you see. And it is my duty, as a Resistance man today, to help you and to show the respect which is due to the members of your family who suffered so much.”

I hold Amy’s hand tightly, smile at Jean-Claude, and whisper, “Merci!”

After a moment, Jean-Claude grins at Monique and says, “There is, after all, a history of Resistance here in Occitania. We still look fondly at those bullet holes from 1621 . . . for us, 390 years is not so long ago. And 1940 and 1942, that is only yesterday. We continue to resist today. Only last year an international seed and chemical company came here and tried to get our farmers to grow genetically altered corn. We resisted . . . and we won! We kicked the bastards out!”

Jean-Claude jumps to his feet, walks rapidly inside, and returns a minute later with a well-thumbed book in his hand: an English edition of The Plague by Albert Camus. “Camus was born in Algeria, where I fought to stay alive for more than two years,” he says passionately. “He knew that the fight against fascism and racism and corporatism is never solely in the past, and never really over. That is what la peste, the plague, is . . . an enemy of humankind that may retreat from time to time but never is truly defeated.” He opens the book to the last page and reads aloud.

“The plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; . . . it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests . . . it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.”

Jean-Claude closes the book, sits down, drains his glass. After a minute, we all stand, reluctantly acknowledging the late hour and the end of this long, intense day. We wish one another goodnight. As Jean-Claude and I clasp hands, he says to me with a rueful smile, “Tomorrow as you drive south, and for the rest of your time in Europe, and when you get back to America . . . watch out for rats!”

I will, I assure him. I will.