SUNDAY, MAY 29, 2011. In the morning after my transfiguring dream, on this day of rest, I perceive, for the first time on our journey, a profound desire to slow down, to pause, to delay any further discoveries of pain or sorrow or even the slightest inconvenience suffered by my uncle and grandfather on theirs. We enjoy breakfast at our ease, lingering at our table to consume with unhurried delectation the last crisp croissants accompanied by fine local honey that we spread with a leisurely knife. Checkout time at Le Bellevue is noon, and we dawdle at packing until the morning hours have all but slipped by. Even then, our bags secured in our sturdy little Meriva, we postpone our departure for still another hour, taking advantage of the hotel manager’s indulgence to occupy a chaise on the rooftop deck while we indolently gaze at the wrinkled blue sea. This is not mere Sunday loafing, I tell myself, it is anxious reluctance. I am deeply aware that our next destination remains a place of infamy within the annals of French and Holocaust history, and, like Jaques’ schoolboy, I find myself “creeping like snail unwillingly” toward tomorrow’s appointment.

At length, we can procrastinate no longer and drive off to the west and south. Returning to the autoroute, we retrace our path to Friday’s intersection with the road to Carcassonne but then continue south on the expressway toward Perpignan and Barcelona, my spirits sent soaring once more by those lyrical names on the green overhead signs. We’re aware that we don’t have far to travel today, so by mid-afternoon we leave the expressway for a smaller highway that hugs the Mediterranean coast and takes us through a settlement called Port Barcarès. It is just a dot on our Michelin map and we imagine a picturesque fishing village inhabited by a colorful array of grizzled watermen and their saucy voluptuous women pulling an honest yet humble existence from beneath the waves. Instead, we find an ersatz town of condos, restaurants, and docks for the outsized compensatory yachts that belong to the Beautiful People who congregate along this portion of the Côte d’Azure. Just outside the port, we come upon a “naturist” community made up of little colonies that sport such names as Eden and Aphrodite, Apollo and Odysseus. We consider taking a prurient detour to try to catch a glimpse of the inhabitants but find that our way is barred by an unsmiling, fully clothed sentry. We retreat, slightly abashed, and spend the next several miles giggling to ourselves at the unlikely prospect that we would ever want to live in such a community. It’s not for us, we conclude, but vive la différence.

We return to the main road and are soon on the western edge of Perpignan near the city airport, where our room for the night is located. For most of our journey, I have endeavored to find charming local lodgings that reflect their particular surroundings, but tonight is an exception. Given what I imagine will be a rather grim encounter next morning, I have made reservations at a nondescript Comfort Inn, a chain motel only a few miles away from Rivesaltes. We find the room to be bland but perfectly acceptable and almost immediately drive into Perpignan for dinner and a little sightseeing.

Now the capital of the departement of Pyrénées Orientales, Perpignan was founded toward the beginning of the tenth century and soon came under the control of the counts of Barcelona. One of those counts, James the Conqueror, founded the kingdom of the island of Majorca in 1276 and established Perpignan as the capital city of the mainland territories of the kingdom. In the next century, the city lost nearly half its population to the Black Death, and during the following three hundred years it passed repeatedly from Spanish to French control and back again as the spoils of many wars between the two countries. Since 1659, the citizens of Perpignan have lived under the French flag, although many street signs today appear in both French and Catalan. In 1963, the Catalan surrealist painter Salvador Dali declared that the city’s railway station was the exact center of the universe and acknowledged that some of his best ideas had come to him as he sat in the station’s waiting room. In Dali’s honor, the city has erected a sign on one of the platforms that reads Perpignan: Centre du Monde.

On this warm late spring afternoon, we leave our car near the thirteenth-century castle of the kings of Majorca and stroll around the high castle ramparts and through the narrow winding streets of the medieval city until we come upon an Italian restaurant in the beautiful Place de la République. We eat heartily; I find myself talking and laughing in an unusually animated manner. Mindful of my appointment in the morning, I have decided this evening to adopt as my mantra Stephen Sondheim’s “Tragedy tomorrow, comedy tonight!” As we return to our motel on the edge of town, however, my spirits sag and sleep comes late.

Monday dawns cloudy and windy. We eat a hurried breakfast in the Comfort Inn’s generic dining area, near a table of pilots and flight attendants who are catching a plane at the Perpignan-Rivesaltes Airport. After loading the Meriva, we set off grimly in search of the nearby camp. A memorial museum dedicated to those who were interned at Rivesaltes is in the planning stages, and I have been in e-mail contact with Elodie Montes of the museum staff. In my last message, I confirmed that I would be seeing her at about 10:00 a.m. today. Anxious to be prompt—on top of my other anxieties—I have left what I assume will be plenty of time to find the site, which, given that it will be the location of a nationally supported museum, I further assume will be clearly marked. To my vast annoyance and frustration, we discover that my assumptions are utterly wrong.

Returning to the A9 autoroute, we become stuck in Perpignan’s rush-hour traffic and then are slowed by an enormous bottleneck caused by a massive construction project involving six lanes of traffic and at least as many exit ramps going off in different directions. Thanks to Amy’s considerable navigational skills, we manage to get off the A9 and onto route D614, which leads us into the center of the small town of Rivesaltes. Spotting a sign reading Musée-Mémorial du Camp de Rivesaltes, we follow its arrow north on the D5, assuming that all will now be easy. But we then come to a traffic circle in which the D5 intersects with the D12, with no further indication of which road to follow. Over the next thirty or forty minutes, we try first one route and then the other, once following another road—the D18—which intersects with D12—but never again seeing another sign indicating that the Musée-Mémorial is any closer than Paris.

Frustrated beyond measure, I can barely take in the landscape, which varies between the verdant vineyards that produce the distinctive wines of the Pyrénées Orientales departement and arid plains that stretch to the rising uplands of the Pyrenees Mountains to the west. The scudding low clouds that obscure the higher peaks match my dark mood.

Finally we see a low building off to our right. We cannot make out what its small sign proclaims but decide that in this storm of uncertainty, we have reached a temporary port. The building proves to have nothing whatsoever to do with the camp—it’s a vocational training center—but luckily the receptionist speaks English and kindly allows us to use her telephone. I reach Ms. Montes almost at once. She was expecting my call but is stuck at the museum’s main office in Perpignan for the next several hours. She gives me detailed directions to the camp entrance and promises to meet me there tomorrow morning at 10:00. So Amy and I decide to push on to our destination for the next two nights, the nearby village of Prades.

But now that we know how to find the camp, my curiosity gets the better of me. We drive a few more kilometers up the D5 until we reach an almost indecipherable crossroads. To the right, a rough dirt road leads off into a tangle of unkempt undergrowth. To the left, standing forlornly by the side of the highway, are three small monuments. One pays tribute to the Spanish Republicans who were interned here after the Civil War. One is for the Gypsies. One is in memory of the Jews.

After a few moments spent gazing at the monuments, we wordlessly drive down the dirt road into a vast, empty, silent space. To our right are a half-dozen giant metal windmills, their blades revolving slowly through the humid air. We see scrubby trees that somehow take sustenance from the dusty grey clay soil. The roadway is treacherous, pocked by deep ruts. A sense of sorrowful abandonment overhangs all.

We come to the ruins of what was once the camp’s main gate, two immense vertical columns supporting the horizontal. There are coils of rusted, abandoned barbed wire twisted among the undergrowth. Driving through the gate, we come upon crumbling brick barracks, most of them open to the cloudy sky. I can drive no longer; we stop and step outside the car into as bleak and desolate a landscape as I could ever imagine. There is the sound of the ever-present wind in the scrubby trees and other than that a silence as profound as might be experienced at the bottom of the ocean.

I am seized by a sadness unlike any I have felt since we landed in Europe nearly three weeks ago. Suddenly I feel an irresistible urge to flee. Amy and I share a glance, we fling ourselves back into the car, and with all speed we make our way out of the camp, head south around the perimeter of Perpignan, and drive up into the foothills of the Pyrenees toward Prades. Neither of us speaks for miles.

Finally, I decide to treat my missed connection with Elodie Montes as a reprieve, an opportunity to return to the role of carefree tourist before tomorrow’s resumption of my pursuit of Alex and Helmut. Indeed, there is much to relish on the journey to Prades, as the highway snakes upward through rock formations and a red-tinged soil reminiscent of the stunning scenery of the American Southwest. Occasional herds of sheep and goats appear in well-tended upland fields and the sky slowly clears as our altitude increases. By the time we reach our destination, my spirits have risen accordingly.

A small village just thirty-five miles from the Spanish border, Prades was founded in the ninth century. Its soaring St. Peter’s Church dates from the eleventh century, with important renovations in the seventeenth century giving it one of the largest and most ornate altarpieces in all France. But its innate beauty aside, there are two reasons why the rest of the world knows about Prades: the monk and mystic Thomas Merton, author of the influential autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, was born here in 1915, and the great cellist Pablo Casals lived here for many years during his self-imposed exile from Spain following the defeat of the Republican forces in 1939. It is the Casals legacy that has inspired me to stay in Prades while visiting Rivesaltes. I am rarely so fulfilled as when I am on pilgrimage.

Our hotel is a lovely stone building that was built as a tannery two hundred years ago. After we check in, we stroll up a steep hill to the city’s main square, which fronts the church of St. Peter. The square is neatly bounded by plane trees, the gnarled trees with the sometimes twisted trunks often painted by Van Gogh; Amy and I have actually taken to referring to them as Van Gogh trees. There are several cafés along the square. We choose one, order sandwiches and beer, and spend a peaceful hour relaxing, reviving, and reveling in the joyful fact of our good fortune to be in such a remote yet beautiful portion of the planet.

We then walk into the cool, dim interior of the church, where we admire the celebrated altarpiece. I reflect contentedly that I am in the same exalted surroundings where Maestro Casals played Bach when he put Prades on the map with his first international music festival in 1950. I imagine that I can hear the echoes of his profound performances reaching me across the decades, and my unsettling memories of this morning are temporarily banished. I am a happy pilgrim as we walk back down the hill to our hotel hand in hand.

But the next morning comes all too soon, and I head back alone to meet Ms. Montes. Amy has decided that after nearly three weeks on my schedule, she needs some time to herself, so she plans to spend the day reading and researching a project of her own by the side of the hotel’s swimming pool. As I drive the thirty miles or so to my appointment, I juggle two conflicting fears. One is that Ms. Montes will stand me up, and the other is that she will appear but will have nothing of consequence to show me. To try to allay those fears and also to brighten up the cloudy day, I slip one of my favorite recordings into the Meriva’s CD player: the Goldberg Variations by Bach, the second of the two commercial performances of the piece made by the great eccentric Canadian pianist Glenn Gould, released just weeks before his death, at age fifty, in 1982. In addition to being a superb pianist, Gould liked to drive, so the thought of his accompanying me on this journey down the mountain enhances my deep enjoyment of the music.

As I take the final curves on the road before arriving at the entrance to the camp, I bet myself that Ms. Montes won’t show. Indeed, when I arrive at the lonely crossroads with the three memorials, I am alone in the vast emptiness. But it is only 9:50, and within five minutes, a little white Renault rounds the bend, pulls up beside me, and a trim young woman emerges holding a folder. It is Elodie Montes. Within minutes I discover, both to my satisfaction and my sorrow, that my other fear was groundless as well.

THE CAMP DE RIVESALTES had its origins in 1935, when the French army, noting that the southwest corner of the country—near the Mediterranean and so close to Spain—was strategically important, requisitioned a little more than fifteen hundred acres of land to build a military base. Roughly two-and-a-half miles long by one mile wide, the base was completed three years later and named Camp Joffre after General Joseph Joffre, a Rivesaltes native who was the commander-in-chief of French forces during the First World War. When the Spanish Republican forces were defeated in early 1939, Camp Joffre was one of several sites, along with the camp at Agde, where refugees from Spain were housed. Within a year, the camp expanded to take in other “undesirables,” including refugees from Nazi Germany, Gypsies, and, especially after the Statut des Juifs of October 1940, Jews. In the last months of 1940, families of these undesirables were moved into the barracks originally intended for French colonial troops. Then, in early January 1941, the camp was euphemistically renamed a centre d’hébergement, an “accommodation center.” Men, women, and children were placed in segregated barracks arranged in a series of îlots, or blocks, designated A through K. The foulest chapter of the history of Camp de Rivesaltes had begun.

Within a very short time, utter misery seized those interned there, due to overcrowding, filth, disease, squalor, exposure to the elements, inadequate food and medicine, and—perhaps most debilitating of all—an utter lack of any meaningful way to pass endless hours behind barbed wire in the vast empty space. Men and women had separate barracks, with an additional section of the camp set aside for mothers with children under six years of age. The barracks themselves, with concrete walls and floors and a single entrance, were each about a hundred fifty feet long and contained up to a hundred people. They slept on bunk beds, the top bunk reached by a rickety ladder, with the beds lined up against each long wall, a narrow aisle stretching between them. As was the case at Agde, the internees at Rivesaltes slept on thin mattresses filled with straw, which was rarely if ever changed. In the four corners of each barracks, there was a tiny room reserved for the very elderly, the very ill, mothers with nursing infants, and, in some cases, someone who claimed—either via election or through sheer intimidation—the title of barracks chief. The one or two windows in each barracks contained no glass; thus it was either stiflingly hot or bitterly cold, depending on the season. The camp’s population continued to expand, until by May 1941, there were an estimated ninety-five hundred people representing sixteen nationalities.

Contemporary accounts of the living conditions at Rivesaltes were stark. One social worker wrote, after visiting one of the barracks, “It was dark, cold, and humid, and there was no heating. And seizing you by the throat upon entering, a bitter odor of human sweat which floats in this den which is never aired out.” Another left this report: “The living quarters are very badly maintained and, with only rare exceptions, are repugnantly filthy. It is impossible to get rid of the vermin that have taken hold there, since there does not exist a systematic disinfecting mechanism. In general, the internees possess only the garment and the underwear that they wear, and the hovels in which they live make it impossible for them to properly look after their clothing.”

The food, such as there was, was bad. Meals always consisted of a thin soup made with potatoes, squash, turnips, parsnips, or cabbage. Occasionally, bread was served along with the soup, but never meat. There was also corn, but not the sort of sweet corn found growing stalk by stalk in the lush fields of Iowa or Illinois. This was feed corn, usually served by French farmers to their pigs; in Rivesaltes, it was fed to the Jews. In the spring of 1941, a representative of a Jewish relief agency visited Rivesaltes and reported that “while the normal daily ration required by a human being lies between 2,000 and 2,400 calories—the essential requirement being 1,500 calories—most of the internees consume barely 800 calories.” The relief worker went on to point out that, due to the cold in the barracks and the often inadequate clothing worn by the unfortunates in the camp, many of those precious calories were lost every day to the exertion of shivering.

One latrine served every three or four barracks. Like the barracks, the latrines were made of concrete. To use the latrine, a person would walk the forty or fifty yards from the barracks, climb a half-dozen steps to a platform divided into five or six spaces that offered the bare minimum of privacy, stood or squatted on two pieces of wood, and contributed to the contents of the large petrol tanks below. From the same relief worker’s report of 1941: “Access to lavatories is generally difficult because of the mud surrounding them. They are so poorly maintained and so rarely disinfected that not only is there a dreadful stink but also a permanent risk of infection, especially during the hot season when flies and mosquitoes proliferate and spread contagious diseases. Rodents have appeared, which besides attacking the food reserves also carry harmful bacteria.”

When the first internees arrived at the newly organized accommodation center of Rivesaltes in January 1941, they found the water pipes frozen and, thus, access to showers nonexistent. This obstacle to cleanliness persisted even with the arrival of warmer weather, as there were few washbasins and the flow of water was frequently interrupted. For weeks, those trapped within the barbed wire were only rarely able to wash themselves and even then, hastily and incompletely. Another eyewitness account declared, “Some internees have not undressed for six months. One can only imagine their present state of destitution.”

The consequences of living in crowded, unhealthy living quarters with a seriously inadequate diet and almost total lack of hygiene quickly manifested themselves. Many prisoners—for that is what they were—soon fell ill. Cases of tuberculosis, dysentery, and enteritis, on top of simple malnutrition and exposure, swept through the camp. Many prisoners died in the arms of family members or, even more wretchedly, alone on their mattresses of straw. Medical facilities within the camp, not surprisingly, were insufficient. Severe cases were occasionally moved to the St. Louis Hospital in Perpignan; an exasperated social worker wrote of the institution, “although it resembles the worst medieval general hospitals, it continues to receive patients.”

In August 1941, the U.S. State Department forwarded a memorandum on conditions at Rivesaltes—written by a relief worker hired by the American Jewish Congress—to a Monsieur de Chambrun of the Foreign Ministry of the Vichy government. The memo concluded, “No self-respecting zoo-keeper would allow the animals in his care to be housed under the conditions prevailing here.” There is no evidence of any reply from the ministry.

Rivesaltes, it must be said, was not an extermination camp. No one there died by design of the authorities. There were no roll calls, no guard towers, no snarling police dogs, no overt brutality meted out by the French guards. There was at least one instance, reported by a survivor whose testimony was videotaped by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, of a coordinated sexual assault by French soldiers. This witness told of soldiers entering one of the women’s barracks and going up and down the center aisle, lifting blankets bunk by bunk to decide which women to take back to their quarters. But for the most part, prisoners were not hounded, harassed, or humiliated.

They were simply left alone in that vast empty space to lean into the constant stiff winds that blew winter and summer, the mistral that stirred up the dust and dirt into little cyclones of torment in the dry season and wrinkled the puddles that covered the endless mud when it rained. They were left alone with no books or newspapers to read, no work to accomplish, no place to walk but on the well-worn path to the latrine, no place to sit but on their bunks in their crowded, uncomfortable barracks, nothing to do but wait or hope or dream increasingly threadbare dreams. Children played with stones and sticks. The days seemed endless . . . and yet they ended far too soon for many prisoners of Rivesaltes.

In August 1942, the Vichy government ordered that part of the camp at Rivesaltes be reorganized as the Centre National de Rassemblement des Israélites, or the National Center for the Gathering of Jews. Foreign-born Jews in the Unoccupied Zone were rounded up, brought to Rivesaltes, and temporarily housed in blocks F, J, and K. Beginning on August 11 and continuing until October 20, nine convoys of prisoners, including both these newly “gathered” Jews and those who had been residents of Rivesaltes for the prior two-and-a-half years, were all loaded onto boxcars and cattle cars and shipped to the extermination camps of Eastern Europe.

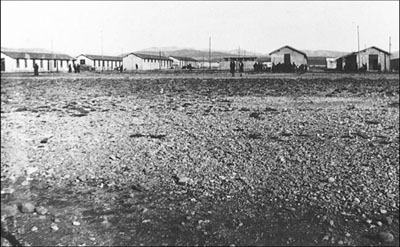

Barracks within the enclosure of Camp Rivesaltes, circa 1941. Today the flat sandy ground is overrun with scrubby stunted evergreens that push their way into what remains of those structures.

(Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

During the years 1941 and 1942, about twenty-one thousand internees passed through Camp Rivesaltes. More than two hundred died in the camp, including fifty-one children aged one year or younger. More than twenty-three hundred were shipped to their slaughter.

In November 1942, the German army invaded the Unoccupied Zone and, finding the camp no longer useful for its murderous purposes, ordered the closing of Rivesaltes on November 25. But nearly two years later, after the liberation of France, Rivesaltes was reopened as Camp 162 to house German and Italian prisoners of war. During the following two years, nearly ten thousand inmates lived there. As proof that the harshness of the camp’s climate respected no national boundaries, more than four hundred POWs died in the camp before it was closed again in 1946.

But the unhappy history of Camp Rivesaltes was far from complete. Beginning in 1954, France waged an eight-year war against the independence-minded population of Algeria, which had existed as a French colony for more than a hundred years. Within that country, there was a sizable population of Algerians, mostly Muslims, who had fought for the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and in both world wars. In the war for Algerian independence, those soldiers, known as Harkis, once more took the side of the French government, and after Algeria secured its independence in 1962, the Harkis were subject to often brutal reprisals from their newly independent countrymen. Many tens of thousands of Harkis were shot, burned alive, castrated, dragged behind trucks, and tortured in other unspeakable ways. Thousands of Harkis fled to France, thinking that the country for which they had fought would shelter them. Instead, the French government refused to recognize the right of these former soldiers to live peaceably within French society and confined more than twenty thousand Harkis behind the same barbed wire fences in Camp Rivesaltes that had imprisoned the Jews twenty years earlier.

Even in the twenty-first century, Rivesaltes has served as a prison for “undesirables.” As recently as 2007, the better-preserved barracks were home to immigrants, many of them also Muslim and in the country without proper papers. The camp, constructed as a base for the French army to prepare for the defense of its homeland, has instead largely served as a place of misery and anguish for nearly eighty years.

ONE OF THE FIRST PIECES of documentary evidence from my grandfather and uncle’s long, sad journey through France that found its way into my hands is a list of Rivesaltes detainees that I discovered among the holdings of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. Listed above such names as Szpitzman, Lippmann, Stern, Levy, and Wiesenfelder, Alex and Klaus Goldschmidt were among twenty men who entered the gate of Camp de Rivesaltes on January 14, 1941—the date it officially opened as an accommodation center—and were assigned to Block K, Barracks No. 21. A dossier was filled out for each of them—No. 222 for Alex and No. 223 for Klaus Helmut—listing their names, the city of their birth (misspelled in Alex’s case), their nationality (German), their religion (“Israelite”), their marital status, and their profession (“salesman” and “student,” respectively).

For six months, they survived the brutal cold, the never-ending mistral winds that Alex declared sapped his strength, the flies and vermin, the suffocating boredom that was only occasionally leavened by letters from his wife and children, and the wretched, inadequate food. Neither of them was particularly robust to begin with, and they both lost considerable weight during their time in Rivesaltes. Alex’s weight dropped from 136 pounds to 104, Helmut’s from 127 pounds to just 94. By the time spring came to the Pyrenees and the chill of their barracks gave way to oppressive heat, Alex feared that they would not live to see another winter. His apprehension was intensified by the brutal evidence of his immediate surroundings. In a letter written to my father in early 1942, Alex declared, “We saw people literally dying of hunger before our eyes.”

Partly to pass the time and partly to earn a small salary that might aid them in acquiring more and better food, Helmut took a job in the camp infirmary, first as an assistant and later as a medical orderly. In that same letter, Alex reported that “part of Helmut’s job was to transfer the dead—sometimes 2 or 3 a day—and carry the bodies out. These were men who, had they had some degree of nourishment, would not have died.”

In his own letter to his older brother, written the following spring, Helmut recounted his days and nights in Block F, the Rivesaltes camp hospital. Given the severe deprivations he and his father faced daily during their imprisonment, I’m struck by the ironic, sometimes almost playful tone my uncle struck in his narrative. Since I never knew him, of course, his words are all I have to form an impression of his character. I must say that I find him very appealing.

First, along with two Spaniards, I was what one could best describe as a “Girl Friday” in the three barracks that served as the infirmary. Then I was “promoted” and made responsible for cleanliness. I had to make the beds of the seriously ill patients (Careful! Lice!), distribute medicine (“pill giver”), take patients’ temperatures, etc. Part of my job took place in the operating room: I served as the Infirmius, in cases of death to help carry off the dead, which was almost a daily occurrence. I also became adept at helping with bandaging. In dealing with sick people I learned a lot, but it was truly not easy. There were two main reasons that prompted me to stay in the job: 1) I didn’t want to and couldn’t do without the meager pay, and 2) I saw no other way to stay out of the Jewish Tent where I visited Father every evening while he was ill. There the care and treatment were even worse. Of course, I didn’t get fat in Block F either.

During those first six months of 1941, as Helmut and Alex struggled to stay alive in Rivesaltes, their dire situation was somewhat ameliorated thanks to the successful attempts of three family members to achieve what they had failed to do: attain freedom in America. The first to make the crossing were Johanna Behrens, the sister of Alex’s wife, Toni, and Johanna’s husband, Max Markreich. Max and Johanna emigrated to the West in 1939, spent months in a displaced persons facility in Trinidad, and finally reached safe haven in the United States in January 1941. Immediately, Max began writing letters on behalf of his relatives and some friends he had made during his time in the West Indies. He wrote to the Mizrachi Organization of America to request that a tallith (a traditional prayer shawl) and a set of prayer books, with texts in both Hebrew and English, be sent to the camp he’d recently left in Port of Spain, Trinidad. And on March 17, he wrote an impassioned letter to a New York Jewish relief organization called the National Refugee Service with regard to Alex and Helmut. “Dear Sirs,” the letter begins,

Alex Goldschmidt is my brother in law, he emigrated together with his son in May 1939 to Cuba, but they could not be landed, because the emigrants on the S/S “St. Louis” got no permits for debarcation. So they returned again to Europe and my relatives came to France, where they have been placed at once in an internment camp. Since that time they changed their stay at several times, and according to a letter which I received just now from Mrs. Goldschmidt (Berlin) they are now in the camp: Ilot K, Bar. 21, Camp Rivesaltes, Pyr. Orientales.

They are all in fear of their lifes, because they will not be able to suffer the awful privations a longer while. And therefore it is necessary to send Affidavit to the American Consul in Marseille on behalf of the above named persons in order to give them an opportunity to emigrate to the States. Owing to the fact that I am a newcomer and without the necessary connexions I beg you to take care of the unfortunate people and to help them as soon as possible.

Hoping to hear from you at your earliest convenience I remain, yours very truly, Max Markreich

His letter seems to have had an effect. About five weeks later, on April 24, Max wrote to a Mr. Coleman at the National Refugee Service, “I have the pleasure to inform you that I was able to procure an affidavit on behalf of Mr. Alex Goldschmidt and his son Helmut in the Camp Rivesaltes. I hope that this fact will facilitate the endeavours to incite the raising of the passage from France to the United States in favour of both internees. Yours very truly.”

The other Goldschmidt family members who managed to escape Nazi Germany and emigrate safely to the New World were my parents, Günther and Rosemarie. Thanks to their membership in the Jewish Cultural Association (the details of which I describe in The Inextinguishable Symphony) and thus their ability to earn a small salary, plus the intercession on their behalf of a former student of my mother’s father (a violin teacher, Julian Gumpert), Günther and Rosemarie were able to book passage on a Portuguese ship called the SS Mouzhino, which left Lisbon on Tuesday, June 10, 1941. The ship docked at Ellis Island on June 21, and my parents were met by Lotte Breger, a schoolteacher who had raised money to help pay for their passage, and Max Markreich, who had received a letter from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee informing him of the date and time of the Mouzhino’s arrival. Within a few days, Günther and Rosemarie Goldschmidt visited the Immigration and Naturalization Service to sign their important “First Papers,” documents indicating their intention to become American citizens as early as the law permitted. They also changed their names, becoming in the course of the afternoon George Gunther Goldsmith and Rosemary Goldsmith.

Thus, with close relatives on American soil and the affidavit process having begun, Alex and Helmut Goldschmidt’s fortunes improved markedly. No longer were they mere “undesirables”; they were now “undesirables” with American “connexions.” The French authorities reacted accordingly, and the wheels of the clumsy machinery that held them captive began slowly to turn in their favor.

The first indication that something had changed was their transfer to a new block of barracks within the confines of Rivesaltes. In early June, they left Block K and were moved to Barracks No. 43 within Block B, a portion of the camp reserved for those detainees with relatives in foreign lands and very real means to join them. From their new barracks, Alex and Helmut wrote a long letter to Günther and Rosemarie, dated June 19, 1941, two days before the young immigrants caught their first exhilarating glimpse of the Statue of Liberty. Alex was, understandably, all business; Helmut could hardly contain his enthusiasm. “Dear Children,” began Alex,

I hope that you will soon have completed your journey across the big pond and that it will have been, in spite of everything, relaxing and beautiful for you after all the strenuous see-saw days of your emigration. I wish you, with all my heart, a full measure of happiness and may all your hopes and plans be fulfilled.

I don’t know whether you received our airmail letter which was sent to Lisbon. It was taken to the post office on May 30th. I’ll briefly repeat that, thanks to Uncle Max M.’s enterprise and his efforts on our behalf, Helmut and I now have affidavits. But I’m not quite sure whether that is enough. Yesterday I was notified by HICEM [an international organization dedicated to helping European Jews emigrate to safety] that the Joint Distribution Committee has deposited $1,000 to cover Helmut’s transportation expenses. Please tell Uncle Max as soon as possible; he is also trying to arrange for our travel costs. In case he has obtained ticket money for us, please ask him to keep it for us.

Last year, in October, when we were sent to Montauban, we lost all our baggage except for my book bag in which I had our documents and my private letters, so we don’t have anything decent to wear, not even underwear or shoes. Even though I assume that before we emigrate—unless it does not happen at all because of some overwhelming event—we shall each receive from the Joint a suit, a pair of shoes, and a set of underwear; what we have now is completely useless. No tramp would consider our suit and shoes worth taking along, and it is urgently necessary, if one wants to get a job or a profession over there, to have some basic things.

The latter worries me a lot, with my meager knowledge of the language. To become completely dependent on my children would be dreadful. I know it would be a crime, after what we have gone through in the last 22 months, to await the end of the war here if there is any alternative. But since one mustn’t gamble with the fate of one’s family and one’s own, the most intensive efforts must be made to get us over there as quickly as possible. I hope to be my old self again in a few months provided it all doesn’t take too long. I am sure that you two are doing everything in your power to get affidavits for Mother and Eva as quickly as possible, so that I can hope to see you all once more in the not-too-distant future. It is this thought that keeps me going and will continue to keep me going.

When we sailed off on May 13, 1939, on the “St. Louis” and you waved to us for such a long time from the dock, we could not have had an inkling that our voluntary separation would become such a long and involuntary one. Please give my regards to Uncle Max and Aunt Johanna. With many good wishes and loving regards, Yours, Father.

P.S. Please send the stamps back for Helmut.

At the bottom of the second page of Alex’s letter, Helmut hurriedly scribbled a few lines of his own:

Dear Rosemarie, dear Günther, I’m sure you can’t imagine how very happy I was when we found out from Mother that everything has now worked out for you after all!! I’ll continue to keep all my fingers crossed! I hope you received our letter sent to the “Mouzhino.” I’ll hasten to finish this so that Father’s letter can go off. More soon . . . And so: Good Luck!!! And then: until we meet again!!! Love, Yours, Helmut.

Nineteen days after they sent that letter to America, on July 8, 1941, Alex and Helmut left Camp Rivesaltes. They had been spoken for; they had “connexions”; they were, it seemed, finally bound for freedom. Placed on a train heading east, they made their way to a new camp near Aix-en-Provence, a camp reserved for refugees with a promising future. I can only imagine the relief they must have felt at leaving behind that vast bleak badlands at the foot of the Pyrenees.

TUESDAY, MAY 31, 2011. What I don’t have to imagine, however, is the image of those badlands themselves. They are here, all about me, as Elodie Montes guides me around the ruins of Rivesaltes. Like me, Elodie has a personal connection to this unholy place. Her grandfather was one of the many thousands of refugees from Spain who were interned here in 1939. When I learn of this essential bond that we share, I wrap her in a spontaneous and heartfelt embrace; she is no longer merely a museum curator but a kinsman of blood and grief.

In the Meriva, we drive slowly for twenty minutes along the dirt roads that wind through the vast expanse, Elodie occasionally pointing out certain landmarks: the relatively grand building that once housed the camp commandant; the Harki barracks, which still retrain a trace of the Algerian designs that some energetic Harki children painted to brighten the concrete gloom; abandoned rolls of barbed wire that lie twisted and rusting among the stunted evergreens that grow wild where once there was only sand and flat desolation. She directs me to Îlot F, the former block of barracks reserved for women with young children. This barracks will soon serve as the central exhibit of the planned museum, and Elodie provides me with a brief history of the project.

A partially reconstructed barrack in Îlot F, part of the planned Rivesaltes museum.

In 1993, after years of abandonment during which a veil of neglect had descended over this bleak plain, the journal of a Swiss nurse who had worked on behalf of the children of Rivesaltes in 1941 and ’42 was published. Four years later, Friedel Bohny-Reiter’s searing words (“The moans of the tormented linger in the air. Even despair has disappeared from these aged, ashen, doleful faces.”) were transformed into a documentary film, just as plans were announced to destroy the camp and erase its memory forever. The film inspired action. In 2000, the French minister of culture included Rivesaltes in a list of historic monuments to be developed, and the governing body of the departement of Pyrénées Orientales gave its unanimous approval to a memorial museum. Over the next decade, Holocaust historian Denis Peschanski was named to lead the overall design team, Rudy Ricciotti won a competition to serve as the architect of the memorial, funds were raised, and construction began. But progress has been slow. Elodie hints diplomatically that she suspects that the right-wing government of President Nicolas Sarkozy has dragged its feet somewhat over the issue of full funding for the memorial. Block F, a tiny portion of the vast holdings of the original camp, has been mostly cleared of its scrubby undergrowth, but that and a rebuilt barracks and latrine are the sole visible evidence that something is being built here to commemorate the brutal legacy of this place.

I did not come here to see a museum, however, but to bear witness. I ask Elodie if she knows which of these ruined remains of crumbling concrete once served as my grandfather and uncle’s dwelling. She pauses, looks down at her folder of papers, and says quietly, “You mean Îlot K, Barracks 21?” Yes, I do. “We can walk there from here.” From Block F, we follow a path westward for a few minutes. We come to a small road that she tells me once served as the boundary between F, the block for women and young children, and K, reserved for Jewish men. Then, after another short distance, Elodie stops before what remains of a building on our right, gently places her right hand on my left shoulder, and nods.

Like most of the ruins on this desolate plain, what was once Barracks 21 has lost its roof and much of its walls. Thorn bushes push through vestiges of windows and crowd the threshold, requiring us to step over them to enter the former interior. Within the broken walls, we stand on a floor made up of the remains of the collapsed roof, invasive weeds, and the inevitable debris and decay of decades: flakes of concrete, random little piles of earth, a shred of faded blue cloth, a small animal skeleton in a corner, some rusty nails, a broken brown bottle, scattered ribs of agave cactus plants, bits of shattered wood. Rot surrounds us.

Elodie picks her way slowly through the obstructions to what remains of the opposite wall, describing how the bunks would have been arranged on either side of the long-vanished aisle. I follow mutely, trying to comprehend that this ruin once was home to eighty, ninety, or one hundred men, two of whom were my grandfather and uncle. Elodie turns to tell me something and then, seeing the stricken look in my eyes, bows her head and starts to weep. “Oh, I . . . I am so, so sorry,” she gasps. We embrace again, huddled against the chilly wind, sharing our sorrow.

More than a little dazed by the bleak surroundings, I stand before what remains of Îlot K, Barracks 21, where Alex and Helmut were housed for six months in 1941.

We return silently to the car and I drive her back to her Renault. I thank her profusely for her time, her information, her empathy, and her kindness, and I ask if I may continue to stay in touch via e-mail. She assures me that my inquiries will always be welcome. We shake hands, possibly mutually embarrassed by our two hugs, and she drives off. I wave, stand still for a long minute, then climb slowly into the Meriva and head back along the treacherous road to Barracks 21.

I stand before what remains of the front entrance. I am alone, with only the wind for company as it sighs heavily, ruffling my hair and growing goose bumps along my arms. I close my eyes, trying my utmost to imagine this blasted heath as it was seventy years ago, when eight or nine thousand souls were crowded together in forced “accommodation,” living on limited rations of nourishment and hope. My imagination fails.

I step up into the space bounded by what remains of 21’s walls and discover that my legs no longer have the strength to support me. I collapse in a corner amid the rubble and find myself speaking aloud to Alex and Helmut. I tell them over and over how sorry I am for them, sorry for the cold and the heat and the wind and the rain and the hunger and thirst and the anxiety and the loneliness and the boredom and the fear and the frustration and the stink and the flies and the sickness and the sadness. I tell them how happy I am that they had each other. I tell them how I wish I could have saved them. I tell them how glad I am that I came all this way to see for myself, and how determined I am to tell their story. And I tell them that I miss them, that I miss them, oh God, that I miss them.

And then I can tell them no more, as I sit crumpled in my little corner, crying like a lost child.

Presently I compose myself, pocket a shard of ceiling as a souvenir, and, before I take my leave of this abandoned place, take out a blue ballpoint pen to scratch a graffito on what is left of a wall. “For Alex and Helmut Goldschmidt,” I write, “who lived in this barracks from Jan to June 1941. I will never forget.”