3.

LITERATURE & LEARNING

DEVON AUTHORS, BY BIRTH & ASSOCIATION

John Ford (1586–c. 1640), born at Ilsington, author of several plays including ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, is regarded as the only significant tragedian of the early Stuart era.

Robert Herrick (1591–1674) was a poet and vicar of Dean Prior from 1629 until 1646 (when removed by Oliver Cromwell) and again from 1660 until his death. London-born, he had a love-hate relationship with his adopted county. One poem suggested a degree of contentment with rural life which he would never have found in London, another referred to ‘loathed Devonshire’, and another still to Devonians as ‘as rude almost as rudest savages’. At the same time, he described with affection the local flora and fauna, some of the local scenes, and country customs of the county.

John Gay (1685–1732), born in Barnstaple, was a poet and dramatist best remembered for writing The Beggar’s Opera, said to have ‘made Rich [John Rich, his producer] gay, and Gay rich’.

Hannah Cowley (1743–1809), born at Tiverton, was the most successful woman playwright of her time, though little remembered today. She was the author of dramas including The Belle’s Stratagem and A School for Greybeards.

O. Jones, a journeyman woolcomber, is remembered as the author of Poetic Attempts (1786), and often referred to as ‘the Devonshire poet’, though little if anything else appears to be known about him.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834), born at Ottery St Mary, leading poet of the Romantic era, best remembered for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. In 1797, he and William Wordsworth (1770–1850) visited the Valley of the Rocks, Lynton, together and decided to write a prose tale, The Wanderings of Cain, but it was never completed.

Jane Austen (1775–1817) spent a holiday in Devon, and set her first novel, Sense and Sensibility (1811), in the village of Upton Pyne, 4 miles from Exeter. The marriage of Elinor Dashwood and Edward Ferrars was set in the village church. Dawlish is also mentioned in the novel.

Charles Dickens (1812–70) wrote the opening chapters of Nicholas Nickleby at Mile End Cottage, Alphington, where his parents lived from 1839 to 1843. The Fat Boy in Pickwick Papers was based on an overweight boot-boy he saw in the Turk’s Head, a fifteenth-century pub in Exeter, which he called ‘the most beautiful in this most beautiful of English counties.’ Pecksniff, in Martin Chuzzlewit, was based on a resident in Topsham. His Christmas short story A Message From The Sea opens with a description of Clovelly by one of the central characters, Captain Jorgan – ‘And a mighty sing’lar and pretty place it is, as ever I saw in all the days of my life.’

Charles Kingsley (1819–75) was born at Holne where his father was curate. His most popular novel, Westward Ho!, was as the title suggests based around North Devon.

Edward Capern (1819–94), ‘the postman poet of Bideford’, was born at Tiverton and spent most of his life in Devon. He was the author of a patriotic verse, ‘The Lion Flag of England’, which was published as a broadsheet and sent to troops fighting in the Crimea. The Prime Minister Lord Palmerston was so impressed with it that he sent for Capern and awarded him an annual pension of £60 from the Civil List.

R.D. Blackmore (1825–1900), educated at Blundell’s School, Tiverton (see p. 55), spent much of his life in Devon, the scenery of which inspired his novels Lorna Doone (Exmoor), and the lesser-known Christowell (Dartmoor).

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) briefly practised as a doctor at Durnford Street, Plymouth – not very successfully, it appears – before deciding to follow his vocation as a writer. His most famous Sherlock Holmes novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles, was set on Dartmoor and partly written while he was staying at the Duchy Hotel, Princetown, in 1901.

Eden Phillpotts (1862–1960), a prolific novelist, writer of short stories, poems and plays, lived firstly at Torquay and then at Broadclyst. Eighteen novels and two collections of short stories comprise his Dartmoor cycle, each one of the series taking a specific area of the moor and describing it faithfully.

John Galsworthy (1867–1933) was born at Kingston-upon-Thames, of Devon ancestry. During an affair with his cousin’s wife Ada, whom he married after her divorce, they moved to Wingstone Manor, Manaton, on Dartmoor. Unlike Ada, who missed the life of London, he preferred the solitude of Manaton, although she persuaded him to return to the city, where they settled until his death. His short story The Apple Tree, on which the film Summer Story was based, was set partly in Devon and inspired by the story of Dartmoor girl Kitty Jay, while another tale, A Man of Devon, was set in the Torquay and Kingswear areas.

Agatha Christie (1890–1976), born at Torquay, ‘the queen of crime’, creator of detectives Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, and author of the west end’s longest-running play The Mousetrap, was at one time reportedly the world’s best-selling author of thrillers. Some of her books feature references to local landmarks and areas of Devon, including Burgh Island, the cliffs at St Marychurch, the Imperial Hotel, Torquay, and Haytor.

Jean Rhys, born Ella Gwendolen Rees Williams (1890–1979), novelist and short story writer best known for Wide Sargasso Sea, spent part of her adult life in Devon. In 1939 she and her second husband Leslie Tilden-Smith settled there for some years. After moving away from the county she returned with her third husband Max Hamer. They lived in Cheriton Fitzpaine, where she was accused on more than one occasion of being a witch. After attacking her accuser with a pair of scissors, she was placed in a mental hospital for a few days. Some years later she died in Exeter Hospital.

L.A.G. Strong (1896–1958) wrote novels, short stories, poems, plays, books for children and non-fiction, as well as broadcasting and lecturing on drama and voice production. He is best remembered for Dewer Rides, a novel set on Dartmoor.

Henry Williamson (1897–1977) spent part of his life in North Devon, his experience of the countryside inspiring his most famous novel Tarka the Otter.

R.F. Delderfield (1912–72), novelist and playwright, was best remembered for A Horseman Riding By and To Serve Them All My Days. His brother Eric (d. 1996) was a noted writer of nonfiction, including titles on Devon historic houses and other aspects of local history, inn signs, and kings and queens.

Victor Canning (1916–86) was born in Plymouth, and though the family moved to Oxford in 1925, he always thought of himself as Devonian, and in later life lived at South Molton for a while. A prolific writer of mostly thrillers, he published 61 books and at least 80 short stories.

Alan Clark (1928–99), Conservative MP for Plymouth Sutton, published several books on military history before beginning his political career.

Ted Hughes (1930–98), Poet Laureate from 1984, bought a house at North Tawton and lived there from time to time until shortly before his death.

Marcia Willett (1945–), wrote several family sagas, including the Chadwick Family Chronicles trilogy, set mostly on Dartmoor and the South Hams area.

Nigel West, pseudonym of Rupert Allason (1951–), Conservative MP for Torbay (1987–97) and military historian, is author of several books on intelligence and security issues, and spy thrillers.

Michael Jecks (1960–) is author of the Templar series of West Country mysteries set on Dartmoor, and part-author of collaborative novels with fellow members of the Medieval Murderers.

Ian Mortimer (1967–), Dartmoor-based historian, author of several medieval histories and biographies, including The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England, and works on Edward III and Henry IV.

REFERENCES TO DEVON IN POETRY & SONG

‘More discontents I never had

Since I was born, than here;

Where I have been, and still am sad

In this dull Devonshire.’

Robert Herrick, ‘Discontents in Devon’

‘Fairest maid on Devon banks,

Crystal Devon, winding Devon,

Wilt thou lay that frown aside,

And smile as thou wert wont to do?’

Robert Burns, ‘Fairest maid on Devon banks’

‘How pleasant the banks of the clear winding Devon,

With green spreading bushes and flow’rs blooming fair!

But the boniest flow’r on the banks of the Devon

Was once a sweet bud on the braes of the Ayr.

Mild be the sun on this sweet blushing flower,

In the gay rosy morn, as it bathes in the dew;

And gentle the fall of the soft vernal shower,

That steals on the evening each leaf to renew!

O spare the dear blossom, ye orient breezes,

With chill hoary wing as ye usher the dawn;

And far be thou distant, thou reptile that seizes

The verdure and pride of the garden or lawn!

Let Bourbon exult in his gay gilded lilies,

And England triumphant display her proud rose:

A fairer than either adorns the green valleys,

Where Devon, sweet Devon, meandering flows.’

Robert Burns, ‘The Banks of the Devon’

‘So Lord Howard past away with five ships of war that day,

Till he melted like a cloud in the silent summer heaven;

But Sir Richard bore in hand all his sick men from the land

Very carefully and slow,

Men of Bideford in Devon,

And we laid them on the ballast down below;

For we brought them all aboard,

And they blest him in their pain, that they were not left to Spain,

To the thumbscrew and the stake, for the glory of the Lord’

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, ‘The Revenge’

‘’Tis eve! ’tis glimmering eve! how fair the scene,

Touched by the soft hues of the dreamy west!

Dim hills afar, and happy vales between,

With the tall corn’s deep furrow calmly blest:

Beneath, the sea! by Eve’s fond gale caressed,

’Mid groves of living green that fringe its side;

Dark sails that gleam on ocean’s heaving breast

From the glad fisher-barks that homeward glide,

To make Clovelly’s shores at pleasant evening-tide.’

Robert Stephen Hawker, ‘Clovelly’

‘Sweeter than the odours borne on southern gales,

Comes the clotted nectar of my native vales –

Crimped and golden crusted, rich beyond compare,

Food on which a goddess evermore would fare.

Burns may praise his haggis, Horace sing of wine,

Hunt his Hybla-honey, which he deem’d divine,

But in the Elysiums of the poet’s dream

Where is the delicious without Devon-cream?’

Edward Capern, ‘To Clotted Cream’

‘And bound on that journey you find your attorney (who started that morning from Devon),

He’s a bit undersized and you don’t feel surprised when he tells you he’s only eleven’

W.S. Gilbert, ‘The Lord Chancellor’s Song’ from Iolanthe, Act II

‘All ye lovers of the picturesque, away

To beautiful Torquay and spend a holiday

’Tis health for invalids for to go there

To view the beautiful scenery and inhale the fragrant air,

Especially in the winter and spring-time of the year,

When the weather is not too hot, but is balmy and clear.

Torquay lies in a very deep and well-sheltered spot,

And at first sight by strangers it won’t be forgot;

’Tis said to be the mildest place in all England,

And surrounded by lofty hills most beautiful and grand.’

William McGonagall, ‘Beautiful Torquay’

‘Take my drum to England, hang it by the shore,

Strike it when your powder’s runnin’ low;

If the Dons sight Devon, I’ll quit the port o’Heaven,

An’ drum them up the Channel as we drummed them long ago.’

Sir Henry John Newbolt, ‘Drake’s Drum’

‘Buy my English posies!

Kent and Surrey may –

Violets of the Undercliff

Wet with Channel spray;

Cowslips from a Devon combe –

Midland furze afire –

Buy my English posies

And I’ll sell your heart’s desire!’

Rudyard Kipling, ‘The Flowers’

WHAT FAMOUS AUTHORS WROTE ABOUT DEVON

Daniel Defoe (c. 1660–1731) described several county towns in A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724–6), although there is some doubt as to whether he actually visited them all, or relied partly on information from his friends who had, and were happy to save him the trouble. Devonshire was ‘so full of great towns, and those towns so full of people, and those people so universally employed in trade and manufactures, that not only it cannot be equalled in England, but perhaps not in Europe.’ He called Honiton ‘a large and beautiful market-town, very populous and well built.’ From Honiton, he continued:

The country is exceeding[ly] pleasant still, and on the road they have a beautiful prospect almost all the way to Exeter (which is twelve miles). On the left-hand of this road lies that part of the county which they call the South Hams, and which is famous for the best cider in that part of England . . . they tell us they send twenty thousand hogsheads of cider hence every year to London, and (which is still worse) that it is most of it bought there by the merchants to mix with their wines which, if true, is not much to the reputation of the London vintners.

Exeter, he noted, was:

Large, rich, beautiful, populous, and was once a very strong city; but as to the last, as the castle, the walls, and all the old works are demolished, so, were they standing, the way of managing sieges and attacks of towns is such now, and so altered from what it was in those days, that Exeter in the utmost strength it could ever boast would not now hold out five days open trenches – nay, would hardly put an army to the trouble of opening trenches against it at all.

Totnes he called ‘a very good town, of some trade . . . They have a very fine stone bridge here over the river, which, being within seven or eight miles of the sea, is very large; and the tide flows ten or twelve feet at the bridge.’ Plympton was ‘a poor and thinly-inhabited town,’ while Plymouth was ‘indeed a town of consideration.’ He recalled being at the latter town the year after the great storm (in other words, probably 1704), during August, ‘walking on the Hoo [sic] (which is a plain on the edge of the sea, looking to the road), I observed the evening so serene, so calm, so bright, and the sea so smooth, that a finer sight, I think, I never saw.’

John Keats (1795–1821) came to Teignmouth for a couple of months in 1818 to nurse his dying brother Tom, and while he was there he wrote part of his poem ‘Isabella, or the Pot of Basil’. He did not like Devon, writing to a friend Benjamin Bailey (13 March 1818) that he had had to wear a jacket for the last three days:

To keep out the abominable Devonshire Weather – by the by you may say what you will of Devonshire: the truth is, it is a splashy, rainy, misty, snowy, foggy, haily, floody, muddy, slipshod county. The hills are very beautiful, when you get a sight of ’em; the primroses are out, – but then you are in; the cliffs are of a fine deep colour, but then the clouds are continually vieing with them.

H.V. Morton (1892–1979), one of the first people to drive round England in the early days of motoring and write about his experiences, waxed lyrical about the virtues of Plymouth in In Search of England (1927), in which he said that:

Every boy in England should be taken at least once to Plymouth; he should, if small, be torn away from his mother and sent out for a night with the fishing fleet; he should go out in the tenders to meet the Atlantic liners; he should be shown battleships building at Devonport; he should be taken to the Barbican and told the story of the Mayflower and the birth of New England; and most important of all his imagination should be kindled by tales of Hawkins and Drake on high, green Plymouth Hoe, the finest promenade in Europe.

Bill Bryson (1951–), who had moved from his native America to live in North Yorkshire and decided he would take one last trip round Britain before moving back to his homeland for a while, visited Exeter, as related in Notes from a Small Island (1995). The city, he wrote, was ‘not an easy place to love’, and he remarked on how after the Second World War the city fathers were given ‘a wonderful opportunity, enthusiastically seized, to rebuild most of it in concrete.’ Restaurants posed a problem, at least for the customer looking for something modest that did not have ‘Fayre’, ‘Vegan’, or ‘Copper Kettle’ in the title, to say nothing of restaurant-less streets and ‘monstrous relief roads with massive roundabouts and complicated pedestrian crossings that clearly weren’t designed to be negotiated on foot by anyone with less than six hours to spare.’ He also marvelled at the logic of being offered a single train ticket to Barnstaple for £8.80, or a return for £4.40, and was impressed by the Royal Clarence Hotel’s offer of a special deal on rooms at £25 a night ‘if you promised not to steal the towels.’

DEVON LOCAL HISTORIANS

Llewellyn Jewitt (1816–86), a Yorkshireman who spent much of his life in Derbyshire, was Librarian of Plymouth Proprietary Library from 1849 to 1853, and published a History of Plymouth in 1872.

Richard John King (1818–79) was Plymouth-born but spent most of his life at Crediton. He was a prolific author, lecturer and journalist on historical and literary subjects and his books include works on Dartmoor and Totnes.

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834–1924) was not only a historian, but a prolific writer of magazine articles, novels, short stories, poems, non-fiction, hymns (notably the words to ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’) and folksong collector. At one time he had more titles listed under his name in the British Museum Library General Catalogue of Printed Books than any other English writer. His best-known book remains Devonshire Characters and Strange Events (1908).

Richard Nicholls Worth (1837–96), born at Devonport, was a senior writer on the Western Morning News for several years, as well as author of works on Devonport, Plymouth and Devon. His son Richard Hansford Worth (1868–1950) shared his interests, though his first love was Dartmoor, and Worth’s Dartmoor, the result of almost a lifetime’s study, was published posthumously in 1953.

William Crossing (1847–1928), born in Plymouth, spent most of his life in South Devon, living for a while at South Brent, then Brentor, then Mary Tavy. His books on the moor, including The Ancient Crosses of Dartmoor (1887) and A Hundred Years on Dartmoor (1901), have regularly been reprinted and are still regarded as among the most authoritative on their subject.

Henry Francis Whitfeld (1853–1908), editor at various times of the Western Daily Mercury and Western Independent, published Plymouth and Devonport in Times of War and Peace (1900).

C.W. Bracken (1858–1950), headmaster of Plymouth Corporation Grammar School from 1909 until his retirement in 1930, published a History of Plymouth the following year, reprinted with a postscript by W. Best Harris (see p. 50) in 1970.

R.A.J. Walling (1869–1949), another journalist who worked on several senior newspapers, was for a while editor of the only Sunday local, The Western Independent. A prolific writer of books on the West Country and of detective novels, his most enduring work, The Story of Plymouth, was published a few months after his death.

W.G. Hoskins (1908–92), born in Exeter, taught local history at Leicester and Oxford and did much to achieve recognition for local history as a subject worthy of academic study. His Devon (1954), part of the New Survey of England series, remains a standard work on the county. His other titles include The Making of the English Landscape (1955), Devon and its People (1959), and Two Thousand Years in Exeter (1960). In 1976 he presented a BBC TV series, The Landscape of England.

W. (‘Bill’) Best Harris (1912–87), a Welshman by birth, came to Plymouth as Senior Assistant Librarian in 1935, and was City Librarian from 1957 to 1974. He regularly wrote, broadcast and lectured on the history of the area, his best-known title being Stories from Plymouth’s History (1969). As a librarian he was naturally a passionate bibliophile. He once stopped three lorries taking books to a corporation refuse tip, bought the lot, and found several rare editions among the collections he had thus acquired.

Crispin Gill (1916–2004), born in Plymouth, assistant editor of the Western Morning News and later editor of The Countryman, made a lifelong study of the city in which he was born, publishing a two-volume history which was later reissued in one volume.

Chris Robinson (1954–), writer, artist and historian, has written and published several works on his home city, including Victorian Plymouth, Plymouth in the Twenties and Thirties, and 150 Years of the Co-operative in Plymouth. He has also presented shows on local radio, and runs a studio gallery on the Barbican.

From the age of the internet, David Cornforth (Exeter Memories) and Brian Moseley (Plymouth Data) have published invaluable and regularly updated histories of their respective cities online.

DEVON PUBLISHERS

All counties have, or have had, several publishers ranging from prestigious firms to cottage industries. This list highlights a selection, including the best-known, local history in most cases being their speciality.

Arthur H. Stockwell Ltd, Ilfracombe. Established in 1898, this has proved the longest-lasting to date.

David & Charles, Newton Abbot. Established in 1960 by David S. John Thomas and Charles Hadfield, this firm rapidly acquired a reputation for its railway and canal histories in particular. It later acquired the Readers Union Book Club, and in 2000 it was acquired by F & W Media International Ltd.

Forest Press, Liverton.

Halsgrove, Wellington. Although having recently moved from Tiverton to Somerset, Halsgrove began as Devon Books, official publishers to Devon County Council, and as such synonymous with high-quality local history titles including the ‘Community History’ series on individual Devon towns and villages.

Macdonald & Evans, Plymouth, were acquired by Harper & Row in 1985 and became Plymbridge Distributors. The company went into liquidation in 2003 and was acquired by the US-based Rowman & Littlefield, later National Book Network International (NBNi).

Obelisk Publications, Exeter.

Orchard Publications, Chudleigh.

Paternoster Press, a Christian publishing company founded in 1936 in London, which later moved to Exeter and was acquired in 1992 by a Christian book distributor, Send The Light.

Reflect Press Ltd, Exeter.

University of Exeter Press.

Webb & Bower, Exeter. Established in 1975 by Richard Webb (a former publicity director for David & Charles) and Delian Bower, it was briefly one of the most successful firms in the country with the runaway success of County Diary of an Edwardian Lady (1977) by Edith Holden (1871–1920), a facsimile of a wildlife diary from 1906 published with the author’s original watercolour illustrations. In 1991 the firm was scaled down and became Dartmouth Books.

Although not strictly publishers, some mention should be made of A. Wheaton & Co., one of the country’s oldest firms, established in Exeter in 1780 by James Penny as a printer and bookseller. It was acquired by William Wheaton in 1835 and taken over after his death in 1846 by his son Alfred, hence the initial in the title. Despite the destruction of the premises on High Street in the Second World War, the company went from strength to strength. In 1965 it moved to a newly built site at Marsh Barton, and next year it was taken over by Pergamon Press, becoming in the process a specialist in producing school textbooks for the British market. The publishing division closed in 1991, but the printing division, now Polestar Wheatons, remains one of the largest printers of British educational and scientific works.

DEVON SAYINGS, EXPRESSIONS & BELIEFS

If you touch a robin’s nest, you will have a crooked finger all your life.

If you destroy a colony of ants, you will always have bad luck. Ants are sometimes thought to be the remains of a fairy tribe.

Conversely, in the early nineteenth century, it was believed that people should kill the first butterfly they saw each year, if they wanted to avoid ill-fortune for the rest of the year. Fortunately, more enlightened attitudes now prevail.

If good apples you must have, the leaves must be in the grave (in other words, trees must be planted after the leaves have fallen).

If swallows fly high, it is a sign of good weather, but if they fly low, they are trying to avoid the coming storms.

To devonshire – to clear or improve land by paring off weed, stubble and turf by burning them and spreading them on the land. The expression is thought to date back to the early seventeenth century, but by Victorian times had been shortened to ‘denshire’ or ‘denshare’.

Dandelion leaves boiled in water with stinging nettles and watercress make a tonic which will ward off all illness, and dandelion flowers picked on St John’s Eve (23 June), hung in bunches around doors and windows, will repel witches.

If picked from a young man’s grave on the night of a full moon, the yarrow is a powerful aid when used to help cast spells, or in working witchcraft.

In Coryton, farmers believed that it was unlucky to take peacock feathers indoors, but in other parts of Devon they were used for ornament and decoration, and were said to bring good luck.

A robin entering a house will bring misfortune with it.

When rooks build nests deep into a tree, close in to the trunk, it is a sign of an impending bad summer.

In February, if farmers found that their hens had stopped laying, the milk from their cows turned pale and thin, or if the butter lost its colour, the snowdrop would be blamed if any were found in the house.

Dartmoor people say that when a snowstorm begins, Widecombe farmers are plucking their geese, and that when the rivers sound loud at night, it is a sign that rain is on the way.

When a full moon comes on a Sunday, the weather in the following month will be bad on land and sea.

The periwinkle, ‘sorcerer’s violet’, or ‘blue button’, was often used as an ingredient in love potions, and regarded as useful for calming hysterics in women. It was sometimes known as ‘cut-finger’ as it was a binder which would stem the flow of blood.

Fleas never infest a person who is close to death.

It is unlucky to go to sea in a ship that has no rats aboard.

Snake-cracking, or taking an adder by its tail and cracking it like a whip quickly to break its back, was once considered a popular sport on Dartmoor. If not done quickly enough, the ‘cracker’ would probably be bitten.

If a Devon maiden prunes the rose at Easter, on Midsummer Day she should pick a rose while the clock chimes twelve, fold it in white paper, and put it away safely in a drawer until new year’s day. She should then fetch it when she gets up on 1 January, and if she finds it is still fresh, she must pin it to her bosom. The man she will marry will meet her that day, and he will try and touch the rose ‘in a gentlemanly way’ if invited to do so. If the unwrapped rose has died, the maid will probably not find a husband at all that year.

A yew tree at Stoke Gabriel would grant your wish if you walked backwards around it seven times.

If three crows were seen together in the Hartland area, they would bring bad luck.

Early in the year, during wet weather, parents in Kingsbridge would tell their children to keep away from muddy lanes until the cuckoo came and licked up the mud.

Fruit stains on tablecloths or linen cannot be removed, until the season for the fruit that caused the stain has passed.

Sewing on a Sunday is not the done thing, as ‘every stitch pricks our Lord,’ while scissors should not be used on the Sabbath either. Hair and nails should not be cut on a Friday.

Finally, and somewhat tangentially, if someone does a Devon Loch, they fail at something when they are very close to winning, usually in a sporting context. The expression comes from Devon Loch, a horse owned by Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother which ran in the Grand National in 1956, and was the favourite to win until inexplicably falling over within 40 yards of the winning post. I say ‘tangentially’, as the animal appears to have had no connection with the county apart from his name.

DEVON DIALECT

Bay-spittle – honey

Crumpetty – crooked

Dashel – thistle

Frenchnut – walnut

Goocoos – bluebells

Goosegogs – gooseberries

Granfer Greys or chuggypigs – woodlice

Grockle – holidaymaker

Horse-long-cripple – dragonfly

Nointed – wicked

Onwriggler – unpunctual, or uneven

Oodwall – woodpecker

Pegslooze – pigsty

Quelstring – sweltering

Skimmish – squeamish

Smarless – smallest

Spuddling – struggling

Storrage – commotion

Devonshire dumplings – people of what are politely called ‘roly poly proportions’

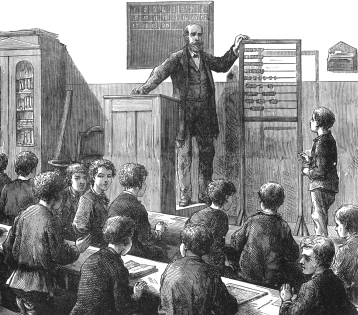

BLUNDELL’S SCHOOL, TIVERTON

Founded in 1604 from a legacy left by bachelor Peter Blundell, a merchant who had made his fortune in the cloth trade, the original premises were vacated when it moved to a much larger site and several more buildings about a mile away on the outskirts of the town in 1882. Now a co-educational day and boarding independent school, it has 350 boys and 225 girls.

Famous alumni

Sir John Eliot (1592–1632), statesman and staunch defender of rights of parliament against Charles I, who was imprisoned and died in the Tower of London

John ‘Jack’ Russell (1795–1883), the ‘sporting parson’ and dog breeder after whom a terrier was named

Frederick Temple (1821–1902), the Archbishop of Canterbury who crowned Edward VII

Sir J.C. Squire (1882–1958), poet, essayist and literary editor

A.V. (Archibald) Hill (1886–1977), physiologist and joint winner of the 1922 Nobel Prize for Medicine

Vernon Bartlett (1894–1983), journalist, author and politician

John Wyndham (1903–69), science fiction author

Donald Stokes, later Baron Stokes (1914–2008), industrialist and chairman of British Leyland Motors

Christopher Ondaatje (1933–), businessman, philanthropist and author

Richard Sharp (1938–), former England Rugby Union captain, said to have been the one after whom Bernard Cornwell’s fictional hero Richard Sharpe was named

George Pitcher (1955–), journalist, author and Anglican priest

Conversely, infamous alumni include:

Bampfylde Moore Carew (1693–1759), rogue, vagabond, imposter, confidence trickster and self-proclaimed king of the beggars.

He was believed to have given up his way of life and settled down after a handsome win on a lottery, which bearing in mind his past history, was probably more than he ever deserved.

C.E.M. Joad (1891–1953), philosopher, pacifist and radio broadcaster, expelled from the Fabian Society in 1925 for sexual misbehaviour at the summer school and barred from rejoining for nearly twenty years, and a persistent fare-dodger on trains until caught travelling without a valid ticket in 1948 and fined £2. The latter disgrace ended his broadcasting career.

Miles Giffard (1926–53), aspiring schoolboy cricketer who longed to turn professional and resented his father’s insistence on finding him more conventional employment. After one too many quarrels with his father, he battered him and then his mother unconscious, threw their bodies into a wheelbarrow and over the cliffs to die, and was hanged for murder.

Famous people who have taught at Blundells include:

Eric Gill (1882–1940), sculptor and typeface designer

Neville Gorton (1888–1955), Bishop of Coventry

C. Northcote Parkinson (1909–93), naval historian and author, of Parkinson’s Law fame

Sir Stephen Spender (1909–95), poet, essayist and novelist

Grahame Parker (1912–95), cricketer and rugby footballer

Mervyn Stockwood (1913–95), Anglican Bishop of Southwark

Malcolm Moss (1943–), Conservative MP

DARTINGTON HALL SCHOOL, NEAR TOTNES

Founded in 1926 by Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst, it was a co-educational boarding school which prided itself on its progressive methods, with a minimum of formal classroom activity and an emphasis on estate activities. At one time it had over 300 pupils. After negative publicity (including old pictures of the headmaster’s wife in a top-shelf magazine), falling numbers and financial problems it closed in 1987.

Famous alumni

Ivan Moffat (1918–2002), screenwriter and associate producer

Lucian Freud (1922–2011), painter

Oliver Postgate (1925–2008), creator of children’s TV programmes including The Clangers and Bagpuss

UNIVERSITY OF EXETER

University College of the South West of England was established in 1922 and became a full university on receiving its royal charter in 1955.

Famous alumni

Robert Bolt (1924–95), playwright and screenwriter

Frank Gardner (1961–), journalist and BBC security correspondent

J.K. Rowling (1965–), author of Harry Potter books

UNIVERSITY OF PLYMOUTH

Formerly Polytechnic South West, it became a university in 1992.

Famous alumni

Philip Payton (1953–), historian

Michael Underwood (1975–), TV presenter

LOCAL NEWSPAPERS

Several towns have their own newspapers. This list includes some of the more general titles:

Evening Herald

Sunday Independent

Western Morning News

Herald Express

Express & Echo

Mid-Devon Gazette

North Devon Gazette

South Devon Gazette

LOCAL JOURNALS & MAGAZINES

Devon Life

Devon Today

Dartmoor News

Dartmoor Magazine