3

Wisdom of the Steppe

On Burkhan Khaldun, one wise person such as Old Jarchigudai could know everything there was to be known, but hidden in the tall standing grass of the steppe were traces of men who had built empires that stretched beyond the realms of Temujin’s imagination. They had left accounts of their successes and failures and advice to future inhabitants carved on the stones across the steppe. Temujin could not read the stone inscriptions, but he was mesmerized by them and knew he would need to learn from their valuable lessons.

The nomadic herders and hunters who had passed over the land in earlier centuries had various names: Kirgiz, Tatars, Naiman, Merkid, Uighurs, and Xianbei, but the most important and famous were the Huns, who created the first steppe empire in Mongolia under their leader Modun in 209 BC.1 According to legend, the Huns shared a close mythical connection to the wolf. The title of their ruler, shanyu, who was also a spiritual leader, may have originated from the word for wolf.

As nomads requiring grass and water and roaming from place to place, the Huns constantly searched for the right relationship with the ever-changing spirits of the landscape. According to Chinese accounts, the Huns, whom the Chinese called Xiongnu, gathered three times a year to offer sacrifices to heaven, Earth, and their ancestors.2 The tribal gatherings provided occasions for ancestral ceremonies of the type from which Temujin and his family had been ostracized soon after the murder of his father. The largest gathering of the year occurred in the fall, when the animals were fattest and healthiest after a summer of grazing. The shanyu carefully controlled the rituals, as this was also the time when taxes were collected.3 Based upon the number of animals owned by a herder and the weather the preceding summer, the shanyu assessed and collected tribute.

The activities that Temujin saw at the court of Ong Khan resembled those of the Huns more than a thousand years earlier. At the Hun gatherings, the shanyu heard appeals, issued judgments, settled feuds, and performed the practical tasks of administration. The acquisition and distribution of goods were the most important part of the political and religious office of the leader, and the two roles were closely entwined. The sacrifice of animals, invocations to the gods, wafting incense, great pots of boiled or charred meat, abundant skins of fermented mare’s milk, and mass rituals involving thousands of people created a powerful spiritual and sensory drama of importance around tax collection and to smooth administration of government.

In the early years of the Hun Empire clear signs of a state cult had already appeared. The Chinese chronicler Sima Qian, who lived at the same time as Modun, wrote that the Huns worshipped “Heaven and Earth and the gods and spirits.” Every day “at dawn the shanyu leaves his camp and makes obeisance to the sun as it rises, and in the evening he makes a similar obeisance to the moon.”4 They often buried their dead with images of the sun and quarter moon. From the beginning of the Hun Empire, their religion glorified the ruler. In a letter to the Chinese court, the shanyu claimed, like the Chinese emperor, to have been chosen by heaven.

During decades of generous rainfall, the luxuriant grasses of the steppe permitted the Huns’ herds to flourish, and with increased milk and meat production, their children grew more numerous and stronger. As their grazing needs surpassed the available pastureland and as these children matured, the older ones left with some of their family’s animals to seek new pastures farther away. Successful herders constantly required more land, and this need created a persistent push outward from the Khangai Mountain valleys and steppe, off the Mongolian Plateau and into farms and villages from China to Europe. Along the way, the Huns occasionally raided the sedentary villagers and, when they had to, traded their prized animals.

Precursors to the Turks and Mongols, the Huns stretched across the continent, reaching India to the south and France to the west. From China to Rome, scholars, soldiers, and bureaucratic clerks began to record their passing, always couched in derogatory comments about these mysterious and fierce people. As the Huns pushed into distant parts of Europe and Asia, they broke into distinct tribes that gradually lost contact with their home base in Mongolia and became small, independently roaming kingdoms.

The Huns left no written record, so our understanding of their history is based on the contemporary accounts of their enemies, supplemented by modern archaeology. The challenge of recording unbiased information about these tribes was demonstrated by the fate of a Chinese court historian in the year 99 BC. The Huns had just routed the Chinese army, but the historian pleaded with the outraged Chinese emperor for mercy for his defeated commanding general. This recommendation so outraged the emperor that he had the historian castrated.5 Facing such dangers, scholars tended to be careful as to what they wrote about the barbarian tribes.

By the time of Attila, the most infamous of all the Huns, in the fifth century, the tribe had reached the western edge of the Eurasian steppes in the land where they had established their own kingdom and to which they gave their name, Hungary. By this point, Huns controlled much of eastern Europe and campaigned throughout Europe, from the Balkans to the Rhine. From their new base on the plains, close to the centers of European civilization, the Huns raced wherever they detected the alluring scent of wealth and weakness, and in the fifth century, the decaying Roman Empire reeked of this irresistible smell.

In the fourth century, Roman warrior and historian Ammianus Marcellinus described the Huns as people from the “Frozen Ocean . . . a race savage beyond all parallel.” What he wrote of the Alan, a steppe tribe related to modern Ossetians, also seemed true of the Huns, with whom they shared a herding lifestyle and political affiliation: “Nor is there any temple or shrine seen in their country,” he declared with amazement, “nor even any cabin thatched with straw.”6

Attila, though he was not the most important or successful leader of the Huns, became the most famous as chroniclers expressed both terror and fascination at his attacks on Rome and cities across Europe. He became the prototype of raiding barbarians everywhere. By his time, the Western Huns had been far from Mongolia for generations, and along the way they had absorbed religious and cultural traditions from many of the peoples they conquered and encountered. They augmented their core beliefs, borrowing a worship of the sword from the Scythians, and absorbing Christian elements into their ideology.

Greek observers and Chinese envoys reported that the Huns practiced scapulimancy, divining the future by reading the cracks and fissures in the charred shoulder blades of sheep, a practice still followed by the Mongols at the time of Temujin. The Huns also consulted seers like Jarchigudai, who read omens and predicted the future, as well as shamans, who were referred to as priests in Greek. Little of the Hun language has survived to indicate precisely what these shamans were called, but the occurrence of the term kam, which is Turkic for shaman, in personal names suggests that the term originated with them.7 The similarity and interchangeability of the words khan and kam for king and shaman in steppe history is a reflection of the near inseparability of religious and political power at that time. Powerful military leaders were considered spiritually gifted and powerful. Only a strongly spiritual individual would win in battle. Such strong leaders were usually men, but often on the steppe women possessed the same mixture of spiritual, military, and political power.8

Latin chroniclers described Attila the Hun as the Flagellum Dei, the Whip of God, sent to punish and scourge humanity. This description would later be applied to many steppe conquerors, including Genghis Khan and Tamerlane.

The steppe nomads did not think of themselves as land conquerors, because land, in their world, seemed nearly infinite. They conquered water, a much scarcer resource. They sought to control rivers and lakes and often called one another by the body of water near where they lived. Attila was the first of the Hun rulers to claim not just the Danube River but all the waters of the Earth. He considered himself ruler of everything within the great sea that surrounded the land. His name, Attila, meant something like Father of the Sea, derived from the same root as Turkish talay or Mongolian dalai for sea.9 Roman chroniclers translated his name into Latin as Rex Omnium Regum, King of Kings,10 and described him as “the lord of Huns, and of the tribes of nearly all Scythia . . . the sole ruler in the world.” Attila named his son and successor Tengis, meaning “ocean” in Turkic and Mongolian.11

While the Huns left a vivid mark on world civilization, they could sustain little direct connection to their original homeland in Mongolia. Following their successful expansion, they were unable to maintain a united world empire, as a series of steppe confederations replaced one another through the millennium. After Attila died in 453, the Hun empire in Europe quickly dissolved. By this time the land they controlled in Mongolia had fractured into competing states, and gradually the Huns faded away, absorbed into many different tribes, nations, and empires. The Huns inaugurated the first imperial era on the steppe, and they lived on in myth and memory long after their eclipse.

Sometime before the eighth century, a new lineage of Turkish khans began to unite the tribes around them from the center of the Khangai Mountains, the original heartland of the Hun nation. They built the first steppe city, their capital Kharbalgas, meaning Black City, near the Orkhon River.12 Almost in reaction to the wandering ways of the Huns, the Turkish khans embraced an ideology of fierce isolation in their homeland, which they called Otukan (Ötükän).

The Turks became the first steppe people to record their history and ideas in wonderful detail. When Temujin left his sanctuary of Burkhan Khaldun, he found the steppe covered with Turkish inscriptions. Instead of lugging heavy books, scrolls, or tablets around with them from one camp to another, steppe nomads carved their messages on stones, thousands of which remain today scattered across the steppe, on the sides of cliffs, scratched into boulders, and carved into mountaintops.13

For centuries, preliterate hunters and herders had left their marks by laboriously carving images onto stones. We find illustrations of deer with elaborate antlers elegantly springing toward the sky, shamans beating drums and dancing in a trance, camels and horses pulling carts. Nearly life-size statues of people from earlier epochs graced the sacred landscapes of the steppe, buffeted by the elements, but respected by the tribes who fought in their wake.

Then, at about the sixth century, the old images gave way to written messages carved on stones in Chinese characters, Sogdian and Sanskrit script, or Turkic runes. For more than five hundred years before Temujin was born, these earlier nomads had been recording their ideas. The steppe nourished an ancient and hardy civilization that spoke in many languages with a loud and clear voice.

Many of the informal inscriptions boasted of a great hunt or offered a single phrase praising a beautiful horse, beloved person, or simply “O, my home,” and “O, my land.” Others commemorated the life and history of the area, and larger ones honored important leaders. The steppe people communicated with heaven through rocks and by carving inscriptions on the sides of mountains. The inscriptions had to be open to the light and sky and not hidden inside a building or buried in the pages of a book, as though they were shameful or secret.

The oldest official state-sponsored memorial appeared in the sixth century in Sanskrit, the sacred language of India, and Sogdian, a trade language related to Persian but written with a Semitic alphabet. This bilingual stone column was mounted on the back of a Chinese turtle-dragon figure, symbolizing the power and authority of the state. Moved from its original location and taken to the mountain town of Tsetserleg, the stone still stands serenely and majestically in the courtyard of a jewel-like Buddhist monastery that fortuitously escaped the socialist plague of destruction that eradicated many religious structures in Mongolia during the twentieth century. The stone was saved by the fact that it had been carried into a museum and turned into history, preserving a message that had survived fourteen centuries. The combination of Chinese, Indian, Persian, Turkic, and Semitic elements demonstrated the cultural complexity and pluralism flourishing on the steppe more than five centuries before Temujin’s birth.

These first inscriptions were called “stones of law,” nom sang, derived from the Greek word nomos, meaning law, and the Persian sang, for stone. The Mongols eventually adopted this phrase to mean “library,” a meaning it still holds in the Mongolian language today.14 The engraved words affirmed the sanctity of the khan, who sponsored the stones and attested to the blessing of history and the spirit world’s approval of his rule. Without such support, the earth, sky, wind, or rain would have thrown down the monument, broken it, and buried it. The engraved words did not just represent the dictates of the state; they were “the great stone of law.”15

Most of these stones appeared in the two centuries between 552 and 742, when a series of Turkic empires controlled large stretches of surrounding territory with their competing clans assuming and losing power in a sequence of short-lived dynasties. For a thousand years up until then, information about the steppe nomads came from their enemies. Beginning with the Turks, the steppe nomads recorded words about themselves.

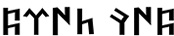

Although the earliest stones erected by the Turkish khans were written in the Sogdian language, the Turks quickly began recording messages in their own language to convey the full complexity of Turkish life, culture, and thought. They wrote in Turkic runes, a simple alphabet of thirty-eight letters well suited to carving in stone or wood, in use on the Asian steppe centuries before the Vikings began writing with similar runes. The Turkic runes consisted of distinct letters, each of which looked very much like a horse brand, similar to ones that continued to be used in Mongolia until the modern era. The people called themselves the Sky Turks (Kök Türk), which they wrote in runes but in the Semitic fashion from right to left— .

.

Temujin had found his whip near the Tonyukuk stone, whose text included the first written use of the name Turk by the steppe tribes. Tonyukuk, a general, offered a final record of his life and advice to future generations of nomads and their leaders, speaking directly through the stones: “I, Tonyukuk,” the inscription began with proud authority. The writing clearly identified the intended reader of the inscription: “You, my younger siblings and the children of my sisters and all my relatives,” or “You, my Turkish people.”

An inscription in stone, like all attempts to write history, should be approached with skepticism. Its author is eager to impose a particular point of view and to provide an account of events for contemporary and future generations. Inscriptions, whether political, religious, or personal, are made as a form of propaganda. Their creation is often accompanied by the destruction of rival messages carved in stone or wood. Inscriptions are intended to restrict the truth and confine knowledge to a single, highly staged image. They are often land deeds or other claims to property or glory, assertions of dubious rights, or boasting to God and humankind of the sponsor’s meritorious deeds.

Yet despite the dubious credibility of what is presented as fact, such inscriptions reveal how people thought and what they valued. In choosing to exaggerate military deeds, acts of compassion, and declarations of love or of sexual conquest, the text reveals what the rulers valued most. What was omitted is always as important as what was included. Historical lies are still cultural truths. They tell us what the people wanted us to believe and what they feared, what they respected and what they despised or desired. The stones clearly exposed the ideals of the era.

Tonyukuk stressed the urgent necessity of tribal unity if his people were to prevail against the enemies perpetually surrounding them. “To bend a thing is easy while it is slender; to tear asunder what is still tender is an easy thing,” he wrote. “But if the slender thing becomes thick, it requires a feat of strength to end it, and if the tender thing coarsens, a feat of strength is required in order to tear it asunder.” By uniting, the tribes could become thick and more difficult to “tear asunder.”

Of all the Turkic stones scattered across Mongolia, the two largest are close together on the Orkhon River, near Karakorum, where the Mongols eventually built their imperial capital. One stone from the year 731, during the Second Turkic Empire or Khanate, honors the life of the general Kultegin, and the other from 734 honors the life of his brother Bilge Khan. Together they had defeated the Tang dynasty’s Emperor Xuan Zong in 721, an incredible achievement for a steppe tribe fighting against the largest military state in Asia.

These monuments were not mere historic markers; they consisted of large stone slabs more than twelve feet high, with carvings on four sides, planted within sight of one another at a distance of about half a mile. “Hear my words from the beginning to the end, my younger brothers, and my sons, and my folks and relatives, hear these words of mine well,” commanded Bilge Khan, the emperor of the Turks. “A Land better than the Otukan Mountains does not exist!”16 It is the center of the world, and who controls it has power over all. “The place from which the tribes can be controlled is the Otukan Mountains.” The point is repeated for emphasis. “If you stay at the Otukan, and send caravans from there, you will have no trouble.”

From the whole of humanity, the Sky had chosen the Turks to live in this ideal place where beautiful rivers watered the land and luxuriant steppes nourished the animals. The inscriptions explained that the First Turkic Empire had violated its destiny when the tribe chose to settle near the Chinese cities of the Tang dynasty, where the sweet foods and words seduced and enervated the nation. The Sky punished them by destroying their empire. Now with this second empire, the Turks once again had the opportunity to flourish in this place, the center of the world. The inscriptions affirmed that law extended beyond the customs of a particular tribe or the commands of an individual khan. Certain moral principles persisted no matter who ruled. The legal and religious ideology of the Turks was simple, direct, and carved into stone.

The stones evidenced belief in a powerful divine law that superceded any individual. As soon as people were created, “over the human beings, a supreme law was created,” pronounces Bilge Khan’s edict.17 This law is known as Toro (Törö). The Turks identified themselves as the people of the law. The Mongols adopted the same concept and used a similar word: tor (töre). Despite regional difference in custom and language, all recognized a set of ultimate principles guiding life. To be civilized was to follow these moral principles, which are natural, divine laws, not man-made ones. Toro is close to the word for birth in Mongolian, suggesting that these principles are there from the moment the Universal Mother created life and at the moment of each person’s birth into this world. They are part of the inner light born within each child that can be seen shining from an infant’s eyes.

Juvaini, who lived among the Mongols near the Turkic stones for a year, examined them and attested to their importance to the Mongols. He described one occasion when new stones were found. “During the reign of the Great Khan [Ogodei], these stones were raised up, and a well was discovered, and in the well a great stone tablet with an inscription engraved upon it. The order was given that everyone should present himself in order to decipher the meaning.”18 That particular stone had been engraved in Chinese and could not be translated until they brought someone from China to do so.

Although some steppe tribes adopted elements of Christianity, Buddhism, and Zoroastrianism, the Sky Turks sternly rejected foreign religions along with other external influences.19 Instead, the Turks developed their own national religion or state cult derived from their ancient animism, without priests or scriptures. They depended on shamans and soothsayers to communicate with their ancestors, to control the weather, predict the future, and commune with heaven. Unlike priests in other religions, shamans had no scriptures, and in a sense each shaman was a different religion, assembling a mélange of stories, rituals, clothes, and sacred objects in a highly idiosyncratic manner; the more unusual their spectacles, the more awe they inspired. What united them was their ritual of beating the drum, dancing, chanting, and going into trance. Theirs was a religion of action and motion, not merely of being or believing.

The messages on the official Turkish stones were more political than spiritual, encouraging the nomads to “follow the water and the grass” and to avoid the customs of the settled nations.20 The Turkic stones offer a clear picture of the steppe as the center of the four sides of the world with the sun rising and setting to the east and west, the forest in the north, and the great Tang Empire to the south. The stones reveal important information about the people of lands far beyond their own, not only other Turks and the Chinese, but also Tibetans, Avars, Kirgiz, Sogdians, and the people of distant Byzantium, which they called Rum.

The writers of the stones understood the temptation of foreign goods and foreign religious ideas, and they proclaimed this mortal danger to the steppe nomads. The messages repeatedly warned of straying away from the steppe and its way of life. The people should stay on the steppe, obey their khans, and worship the sky and earth.

Bilge Khan articulated a clear political and moral message beyond praising his Ashina clan and boasting of his power. He saw that the Turkic dynasty before him had been seduced by civilized life in China and, like the Huns who headed for Europe, they never returned.21 And so he warned his fellow nomads to avoid sedentary civilizations. He warned them in clear terms of the demise of his Turk predecessors who went to live in China: “Your blood ran like a river, and your bones piled up like a mountain; your sons worthy of becoming lords became slaves, and your daughters, worthy of becoming ladies, became servants.” The same sentiment was recorded later by another Turk who warned against contact with other civilizations. “When the sword rusts the warrior suffers, when a Turk assumes the morals of a Persian he begins to stink.”22

Despite the vehement denunciation of all things foreign, the stone texts show clearly that the Turks had already absorbed many ideas from foreigners, particularly the Chinese and Sogdians. The early Turkic engravings displayed a sophisticated cosmography. Father Tengri ruled the heavens, Mother Umay ruled the earth, and the khan ruled the people. The primary spiritual force of the Turkic state was the Sky. Tengri was not a supreme God so much as a vast reservoir of spiritual energy that inspired and guided men by granting them power and fortune or denying them. The sky was an ocean of light and functioned like a giant spirit of the universe, animating humans by granting them a soul and a destiny. In the same manner that the Sky provided the destiny of animals and people, it granted tribes, clans, and nations their individual destinies.

According to some accounts, Tengri was a broader concept of the divine and not confined merely to the sky. The Islamic scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari, writing about the beliefs of the Turks (whom he called Infidels) around the year 1075, offered this view: “The Infidels—May God destroy them!—call the sky Tengri; also anything that is imposing in their eyes they call Tengri, such as a great mountain or tree, and they bow down to such things.”23

The Turkic Tengri was the same heaven worshipped by Temujin as Tenger.24 As a somewhat removed sacred presence in the universe, Tenger rarely intervened in daily affairs. It designated someone on Earth to manage the mundane affairs of the people, and this was the khan. People could discern the thoughts and words of the divine through the actions of their ruler. Tenger spoke to people only when it was necessary to reinforce the power of their designated khan. To explain why the Turks had suffered from such ill fortune in an earlier era, the inscription on Tonyukuk’s memorial offered that heaven must have said: “I had given you a khan; but you abandoned your khan.”25 The text makes it clear that no person actually heard these words; Tonyukuk deduced this meaning based on the punishments the people had endured. It was the Will of Heaven, not the Voice of God.

The inscriptions carved into stones and dotted across the steppe display a fierce fatalism by a people resigned to a preordained destiny who felt no need to place a supernatural explanation on whatever happened. At death, one’s mortal remains of bone and flesh rotted and the immortal part of the soul simply flew away or rose up to the sky. One may be tempted to think that the soul departed the body and went to heaven, but no such destination was stated. If the Turks of that time believed in an afterlife or in reincarnation, they did not reveal it through their written messages.

Life is simply life, and death is death. When Kultegin died in 731, his elder brother Bilge Khan recorded his grief. “I mourned. My eyes, which have always seen, became as if they were blind, and my mind which has always been conscious became as if it were unconscious.” He voiced a simple message that became a persistent theme in steppe spiritual philosophy in the coming centuries: “Human beings have all been created in order to die.” In facing such pain, the Turks had to look to their own disciplined minds for guidance. “When tears came from the eyes, I mourned holding them back, and when wails came from the heart, I mourned turning them back. I mourned deeply.”26 Despite Bilge Khan’s demonstrable pain, there is no sense that heaven should or could have intervened in the life of a single person, not even a person as high ranking and important as the khan’s brother. Precisely the same fatalism permeated the life and deeds of Temujin. Action was always more important than mourning or complaining.

History shows that nations often enjoy the richest luxuries and raise the most imposing monuments to themselves immediately before they fall. Rather than marking the height of Turkic imperial power on the steppe, the impressive Turkic monuments chronicled the end of their great empire, when rulers proclaimed their greatness through their words more than through their accomplishments. The boasts carved on the stones endured, but the empire of the ruling Ashina dynasty perished. Their former subjects, the Uighurs, rose up, overthrew them, and declared a new empire in the year 742 with the justification that the sacred land Otukan had withdrawn its blessing and abolished the charisma of its khan from the prior dynasty and bestowed it on the Uighurs. Over the coming centuries, descendants of these early Turkic tribes would found far greater empires in India and modern-day Turkey, but their heyday in Mongolia had ended.

Temujin could not read the inscriptions on the Turkish monuments, but in time he acquired followers who could. The important lessons of the Turkic rulers passed into the oral history and the lore of the steppe. Temujin was able to absorb many of these lessons and, just as important, to learn from their failures. These earlier Turkish rulers had been much more successful in creating an empire and in dealing with outside nations than the khans he had known, so he paid close attention to their messages. And yet he showed no compulsion to obey their instructions or commands.

Though interesting and important, the advice outlined on the stones was not to his mind part of the immutable law of the heavens. It offered temporary solutions to the problems of a particular situation. Temujin decided that he could pick and choose which piece of advice to accept and which to ignore. He agreed with the stones’ spiritual teachings about Earth and the Will of Heaven and their injunctions about unity and the corrupting influence of cities, but he rejected their isolationism and antiforeign sentiment. In time, he came to believe that the steppe tribes could not have a good life without products and goods from distant places. He founded his empire on military strength and victory in battle, but to secure and expand it, he decided to encourage and facilitate trade.

The stones on the steppe and the experiences of the earlier Huns and Turks showed him two contrasting paths. Temujin searched for a new path between the total dispersion of the Huns across Eurasia and the stubborn but unrealistic isolation of the early Turks. He wanted to remain Mongol while conquering the world.