4

THE HEART SUTRA has two versions: a shorter text and one that is longer. The shorter text, which came to be known first, has been chanted in regions where Chinese ideographs are used. The longer text has been chanted in Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, and Mongolia.

Although there is a Sanskrit version of the shorter text, it is seldom chanted. The principal Chinese version that corresponds to the Sanskrit version is a translation by Xuanzang (604–664). His name is also spelled Hsüan-tsang, Hiuen-tsiang, Yüan-tsang, and Xuanzhuang.

The Xuanzang version is the shortest of all extant Chinese renditions of the sutra, with the main part consisting of only two hundred seventy-six ideographs. It is regarded as supreme in its clarity, economy, and poetic beauty. It is commonly chanted in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Consequently, East Asian teachers who have founded Buddhist groups in the West rely primarily on the Xuanzang version.

The Heart Sutra’s story weaves its way through the life and work of this ancient Chinese monk. My source is a biography by Huili, a disciple who edited many of Xuanzang’s translations. After Huili’s death, Yancong, another student, completed the biography in 688. Titled Biography of the Tripitaka Dharma Master of the Da Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty (Datang Da Ci’en-si Cancang Fashi Chuan), it is regarded as the most detailed and accurate biography of Xuanzang available.1 Here, in brief, is his story:

In the autumn of 629, twenty-six-year-old Xuanzang broke the Chinese imperial prohibition on traveling abroad and set off on a journey westward for India in search of authentic dharma.2 After diligently seeking out the best scholars in Buddhist philosophy and extensively studying Mahayana as well as earlier scriptures in Shu (Sichuan in western China) and Chang’an — the capital city of the newly formed Tang Empire — he realized something crucial was lacking. He particularly wanted to obtain scriptures not available in China at that time, and find solutions to unanswered questions on the “Consciousness Only” theory in the Yogachara (Meditation Practice) School — the most advanced Mahayana philosophy.

After his fellow travel companions had given up and his local guide attempted to stab him, Xuanzang continued alone on a skinny, aged horse. He traversed the vast, flowing sand dunes on Central Asia’s caravan path in the southwestern tip of the Gobi Desert. (This intercontinental route was named the Silk Road by the German geologist Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877.)

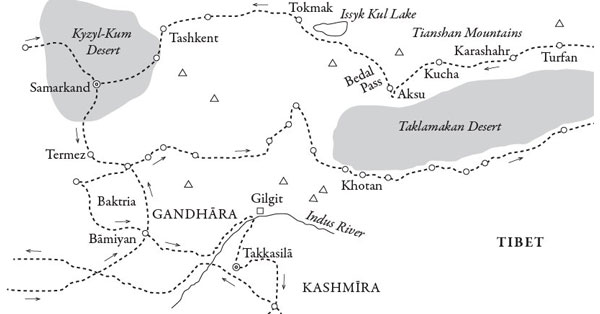

FIG. 1. Xuanzang’s routes: China–India.

Xuanzang slipped through the five watchtowers of the Yumen Barrier, the furthest western outpost of China, on his way to Hami. He walked for days, getting lost under the brutally scorching sun. Thirsty and exhausted (probably to the point of hallucination), Xuanzang found himself surrounded by grotesque evil spirits. Again and again, he invoked the name of his guardian deity, Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, but the spirits persisted. As he fervently chanted the Heart Sutra, they were finally driven away.

The scripture Xuanzang chanted had a special personal meaning. When he was studying in Shu, he came upon a poor monk who had festering sores all over his body. Pitying his sickness and stained clothes, the young Xuanzang took him to a local temple where he found money with which the monk might purchase food and clothes. As a token of his gratitude, the sick monk taught Xuanzang the Heart Sutra. Xuanzang continued to study and chant it for years.

When Xuanzang reached the temple in Hami, the king of the oasis state invited him to the palace and made offerings. The envoy of Turfan, who was also present, noticed Xuanzang’s profound personality and reported back to his king about the monk who had just started a long pilgrimage. Xuanzang was unable to resist a cordial invitation sent by the Buddhist king of Turfan, so he made a detour to visit Turfan, crossing the northeastern end of the Taklamakan Desert through the southern foot of the snowcapped Tianshan Mountains.

The king, overjoyed and impressed, asked Xuanzang to be the preceptor of the nation. Although he politely declined, the king forcibly insisted. Xuanzang fasted to show his determination to continue his search. Three days passed. When the king saw that Xuanzang was already becoming emaciated, he withdrew his command and asked Xuanzang to stay for one month and give dharma discourses to his subjects. Upon the monk’s departure, the king made an offering of clothing suitable for his travel ahead, a large amount of gold and silver, and hundreds of rolls of silk — enough to sustain his journey for twenty years — along with letters of introduction to twenty-four kings and khans in the Eastern and Western Turkestan regions. He also provided thirty horses and twenty-four helpers.

When Xuanzang and his large caravan were on their way to the next oasis kingdom of Karashahr, they were stopped by a group of bandits who had just killed all the Iranian merchants traveling ahead of his caravan. Fortunately, the guide of Xuanzang’s expedition gave the bandits money and everyone got through. In the flourishing kingdom of Kucha, the king, with a great many Theravada home-leavers, welcomed him with music and feasting. After a three-month sojourn, Xuanzang pushed westward to Aksu in an attempt to cross the Bedal Pass through the high and steep Tianshan Mountain range covered with glaciers. During an arduous climb in a snowstorm, the pilgrim lost one-third of his crew as well as many oxen and horses, which succumbed to freezing and starvation.

Reorganized at the southern side of the huge Lake of No Freezing, Issyk Kul, the shattered caravan made it to Tokmak. There Xuanzang was greeted by the Great Khan of the Western Turks, who reigned over most of Central Asia and beyond. The Khan also tried to persuade him to stay, but eventually Xuanzang had him write notices of safe passage to the rulers of nations on the path of the monk’s impending journey. It was the summer of 630. Almost a year had now passed.

After stopping in a forest with a number of small lakes, Xuanzang visited villages and kingdoms on the northwestern side of the Tianshan Mountains, meticulously recording their names and locations. He journeyed through more kingdoms west of Tashkent until he crossed the Desert of Red Sands, Kyzl-Kum. Finally he arrived in Samarkand, a prosperous trading kingdom of Sogdians, most of whom were Zoroastrians. Its king was unfriendly to the pilgrim at first but soon changed his attitude, not only taking the precepts from the monk but asking him to ordain other monks as well.

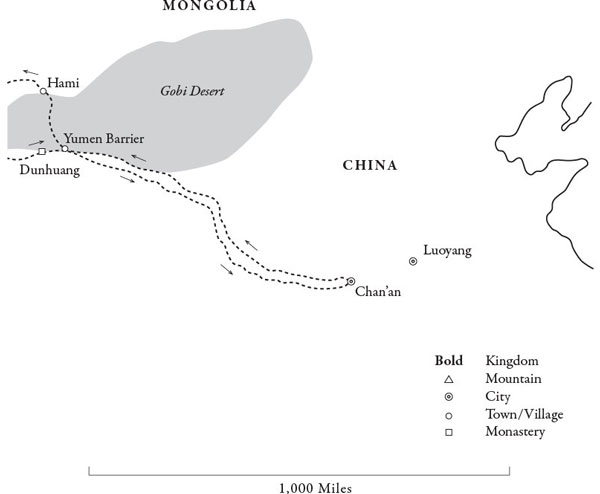

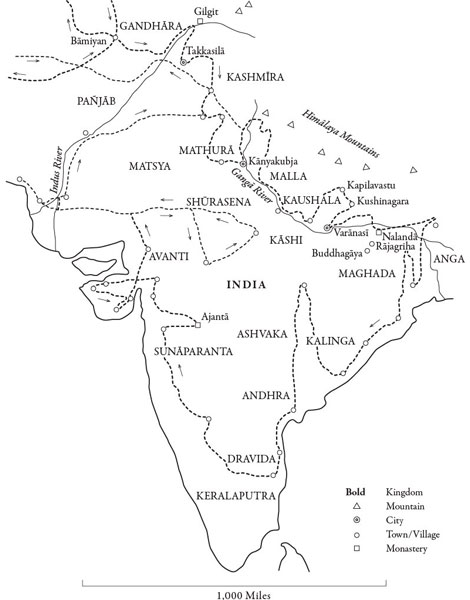

From Samarkand, Xuanzang turned south, visiting ancient Buddhist sites in Termez, Kunduz, Balkh, and Bamiyan. He then set out to the southeast, passing the Gandhara and Kashmir regions. Entering the subcontinent of India, he visited sacred sites in Mathura, Shravasti, Lumbini, Kushinagara, Sarnath, Vaisali, and Buddhagaya (present-day Bodh Gaya).

In the autumn of 632, after a three-year journey in which he miraculously escaped myriad dangers, Xuanzang arrived at the Nalanda University Monastery in the kingdom of Magadha in northeastern India. Buddhism was flourishing, and Nalanda, with over ten thousand students, was the center of Buddhist studies. Xuanzang met the abbot Shilabhadra, a renowned master of Yogachara, said to have been one hundred and six years old. Three years before, Shilabhadra had had unbearable pains in his limbs and wanted to end his life by fasting. But Manjushri Bodhisattva, deity of wisdom, and two other bodhisattvas appeared to him and said that a Chinese monk was on his way to study with him. From that moment, Shilabhadra’s pains went away. The old master recognized Xuanzang as the monk he had awaited.

Shilabhadra (circa 529–645) came from a royal family based in Samatata in eastern India. After traveling in search of a master, he arrived at Nalanda, where he met Dharmapala (530–561). Dharmapala was a young and brilliant leader of the monastery, as well as a theorist in the Yogachara School, which practiced a succession of stages of bodhisattvas’ yogic meditation. This school had been established by Asanga and his brother Vasubandhu in the fourth century, based on the philosophy that all existences are representations of the mind and no external objects have substantial reality. Dharmapala was the compiler of the Treatise on Realization of Consciousness Only, in which he included ten other thinkers’ commentaries.3 At age thirty, Shilabhadra represented his master, Dharmapala, and established a reputation by defeating a non-Buddhist thinker in a debate. He later became Dharmapala’s successor.

FIG. 2. Xuanzang’s routes: India.

In the company of thousands of other students, Xuanzang listened to Shilabhadra’s lectures. For five years, he studied various Buddhist texts, the Sanskrit language, logic, musicology, medicine, and mathematics. He also conducted an in-depth investigation of the Consciousness Only theory under the tutelage of Shilabhadra. Xuanzang then proceeded to write a three-thousand-line treatise in Sanskrit entitled Harmonizing the Essential Teachings in an attempt to transcend differences between the major Mahayana theories: Nagarjuna’s Madhiyamika and Asanga’s Yogachara. It was highly praised by Shilabhadra as well as other scholarly practitioners, and came to be widely studied. Xuanzang also wrote a sixteen-hundred-line treatise entitled Crushing Crooked Views, advocating Mahayana theories.

After collecting scriptures, visiting various Buddhist sites, and giving discourses in the eastern, southern, and western kingdoms of India, Xuanzang continued to study with dharma masters in and out of Nalanda. When Xuanzang received permission from Shilabhadra to return to China, King Harshavardhana — ruler of the western part of northern India — eagerly invited Xuanzang to his court in Kanykubja on the Ganges. He was a supporter of Hinduism and Jainism, as well as various schools of Buddhism. In the twelfth month of 642, the monarch invited spiritual leaders from all over India to participate in an exceedingly extravagant philosophical debate contest. Representing Nalanda, Xuanzang (whose Indian name was Mahayanadeva) crushed all his opponents’ arguments and was announced the winner by the king. Harshavardhana then provided the homebound pilgrim with his best elephant as well as gold and silver, and organized a relayed escort for Xuanzang’s caravan all the way up to China.

In an early part of his journey home, one box of scriptures carried on horseback was washed away in the crossing of the Indus River. Xuanzang spent some months waiting for its replacement. From Kashmir, he and his party climbed through the Hindu Kush and Pamir mountains. They stopped at the great Buddhist kingdom of Khotan, then toiled through the southern end of Taklamakan Desert. From there, they made a brief stop at Dunhuang before going back to the Yumen Barrier, where they waited for imperial permission for Xuanzang to finally reenter his homeland. Bearing relics and images as well as 657 Sanskrit sutras and commentaries, all carried by twenty-two horses, Xuanzang returned to Chang’an at the beginning of 645. It had been a sixteen-year journey. Hundreds of thousands of people greeted him.