7

In Print for One Thousand Years

JOHANNES GUTENBERG’S invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century led to a wide circulation of the Bible and other books in Europe and eventually throughout the world. The earliest known printed sheet, however, is that of the Sutra of Great Incantations. Discovered in Korea, it is dated 751, preceding Gutenberg by seven centuries.1 The earliest surviving copy of a printed book is that of the Diamond Sutra, dated 868, which was brought to England from one of the caves in Dunhuang on the Silk Road by a Hungarian archaeologist named Aurel Stein, who was leading the British Expeditionary Party in 1907.2

Founding Emperor Tai of China’s Song Dynasty sent his messenger to the lord of the western region of Shu in 971, and ordered the carving of printing blocks for the Tripitaka. Printing technology had already been developing in this region. By 983, the carving of the canon was completed, and over 130,000 woodblocks were transported to the capital city of Kaifeng in central China. Printing started in the following year. This epoch-making edition of the Tripitaka is known as the Shu version.3

Members of the Tartar tribes of Manchuria, the Khitan, completed printing of a Chinese-language Buddhist canon in 1054. The print has been lost, but its table of contents still exists and shows that the Heart Sutra was included in this printing.4 This version of the canon became the basis for the stone-carved sutra on Mount Fang (present-day Mount Danjing, Henan Province). A stone rubbing of the Heart Sutra shows that it has a Chinese title, but the text is a Chinese transliteration of the shorter Hridaya text written out by Maitribhadra, a northeastern Indian monk who came to Khitan in the early tenth century.5

Following the publication of the Shu version of the Tripitaka, versions of the Tripitaka in Chinese-originated ideographs were printed in China, Korea, and Japan. (Presumably Xuanzang’s version of the Heart Sutra was included in all versions of the printed Mahayana Tripitaka.)6 As one of the most widely demanded scriptures in the ideographic canon, the Heart Sutra has been independently printed quite frequently, using the woodblock of the sutra taken from the entire set of printing plates. This makes it a text that has been in print for more than a thousand years — one of the longest living texts in the history of printing.

The woodblocks of the Shu version of the Tripitaka, however, were destroyed during an invasion by the armies of the northeastern Chinese kingdom of Jin in 1126. That leaves the woodblocks of the Korean Tripitaka as the oldest existing plates of the Buddhist canon.

In 1011, Emperor Hyeon of the northern Korean kingdom of Goryeo initiated the reprinting of the Shu version of the Tripitaka with the intention of protecting the nation from invasions by the Khitan. The printing was concluded decades later, but the woodblocks were destroyed in war. Additional sutras were subsequently collected, and printing of an expanded edition of the Goryeo Tripitaka was completed in 1087. The plates for this later version were burned during the Mongol invasion of 1232. But in 1236, under imperial order, monk-scholars led by one named Suki started comparing all available versions of the scriptures in order to establish an entire text for the expanded Goryeo Tripitaka. (Suki later published his team’s comparative annotations in thirty fascicles.) In 1251, the printing was complete. Among the 52,382,960 engraved characters in this version, not a single mistake has been found.7 After being moved twice by imperial edicts, the 81,137 woodblocks of the Goryeo Tripitaka — carved on both sides, and including 1,511 scriptures — found their home at the Haein Monastery in South Korea. They have been there since 1398.8

This Tripitaka became the basis for three versions of the ideographic canons published in Japan, the last of which is the one-hundred-volume Taisho Canon (Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo), edited by Junjiro Takakusu and others, published between 1923 and 1934. The Taisho Canon, which with over 120,000,000 characters is the world’s largest printed book, is an invaluable source and the one most frequently referred to by Buddhist scholars today.

• • •

As part of my research for the present book, I wanted to see the Heart Sutra as it appears in the Goryeo Tripitaka, in its living environment. In late October of 2004, I flew to Busan, a southeastern port city of the Korean Peninsula. Taijung Kim, a renowned calligraphy and painting teacher, met me with one of his students, Hyuntaik Jung, at a hotel in Busan. It was about a three-hour drive, and much of our communication was done with an improvisational mixture of spoken languages and written ideographs.

In a guest facility of the monastery, I was given an unfurnished room of traditional hermitage size — roughly ten by ten feet, in a large building called the Authentic Practice Hall, now being used as an office and residence quarters.

That afternoon, my new calligrapher friends and I had less than one hour to visit the large, modern-style museum of the monastery. There, a printing plate for the forty-fifth fascicle of the Avatamsaka (Flower Splendor) Sutra was displayed behind a glass case. It was dated 1098, so it must have been a surviving block from the second Goryeo Tripitaka. The size of the board, oriented vertically, is seventy by twenty-four centimeters. In the center of the relief surface, a column of characters indicates the title and the fascicle number of the sutra. Such a column is usually shown at the front spine of a book as a quick reference for the title of the sutra. A print from this slab must have therefore been folded in half and intended to be a book. Thus, we can guess that the second Goryeo version was in book format as opposed to scroll format.

The writing on the printing plate is engraved in reverse, of course. The printed text in Chinese reads vertically, progressing from right to left. Though there is no punctuation, there are paragraph changes. The prose has no character spaces, but in the poems, each verse is followed by a blank space the size of a single ideograph. If the plates I saw were typical, I estimated one plate to have a maximum of twenty-six columns, with twenty-two characters per column.

Next to the Avatamsaka plate was a display of the Heart Sutra. Unfortunately, it was a blackened copper replica. I had wanted to know how worn out it was, compared with the blocks of other sutras. This “woodblock” made of copper had almost no signs of wear. Nevertheless, the replica shows us the format of the Heart Sutra plate in the later Goryeo edition. Metal tabs, nailed to the edges, keep the plates from sticking to each other and allow airflow between the plates.

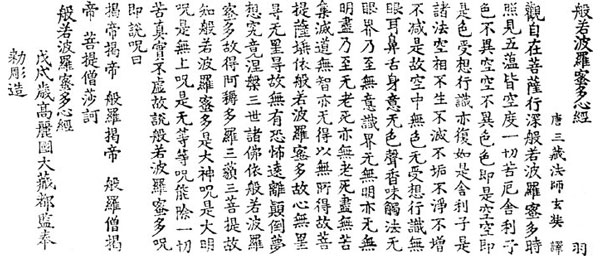

FIG. 3. Later Goryeo version of the Heart Sutra. Chinese. Print.

There is no extra column for the title of the sutra in the center. This means that the later Goryeo version prints must have been mounted on scrolls. Fourteen characters each are carved on twenty-five columns per plate, making it smaller than the earliest version.

I had previously seen a photographic reproduction of the Heart Sutra in this later version of the Goryeo Tripitaka. It showed that the title of the sutra was Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra, without the first word, Maha. Underneath this title was the single symbol yu (“feather”), an ideograph from the One Thousand Character Text by Zou Xingsi (d. 521) of the southern kingdom of Liang, composed of unrepeated symbols. Here, yu served as a library index code for the sutra.

The colophon of the scripture read as follows: “In the senior-water dog year, the Director of the Tripitaka Bureau engraved this under imperial command.” The Chinese cyclical calendar combines the ten elements — five (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water) times two (“senior” and “junior”) — and the twelve zoological signs. These symbols collectively cover the span of sixty years, which represents a complete calendar cycle. This cyclical calendar is a common system in East Asia, where the calendar based on imperial eras changes frequently in accordance with the monarchic reigns. Here we can determine that the “senior-water dog year” corresponds to 1238 C.E.

As in the prints of other sutras in the later Goryeo version, each character of the Heart Sutra is exquisitely written and engraved. Most characters are tall, and what makes this edition calligraphically unique is that the characters are slightly tilted toward the left. Tilting is generally avoided in East Asian calligraphy. In this case, however, it works mysteriously well, creating a kind of hypnotic effect.

Each line seems to have been carved quickly but very precisely, often with beginning or ending pressure points, which loosely correspond to serifs in Western calligraphy. Seeing these meticulously carved characters, I could believe the legend that the wood carvers made three full prostrations after carving each ideograph. Looking at each one of these printed characters, I too felt like making three bows.

The aesthetic supremacy of the Goryeo version of the Tripitaka is widely accepted. And because of its consistent calligraphic style, it is believed that a single (now unknown) calligrapher wrote over fifty-two million characters before a team of carvers engraved them.

Soon after this, I went to the museum bookstore and asked a woman behind the counter, who seemed to be the manager, if she had a print of the Heart Sutra for sale. She took out a folded print from her file and showed it to me. It was printed in light gray with an attachment in Hangul — the Korean phonetic script — mixed with a small number of ideographs.

Evidently, this print was made for tracing the sutra. The attachment is a prayer with blank columns for the devotee’s name and address as well as the date. At the end, it says in ideographs, “To be enshrined inside the stomach of the Shakyamuni Buddha image.”

I gestured to the woman that I wanted to buy it. She wordlessly indicated that she would simply give it to me. I accepted it, bowing with my hands together, at which time she signaled that the attachment was not useful to me and quickly cut it off with a knife. She was about to throw it away when I stopped her and said I needed it. (Later, when I took time to examine it, I found four ideographs in the middle of the Hangul prayer: “my diseased father and mother.” Perhaps she sensed that I was not going to offer a prayer in Korean for my parents.)

Shamelessly I motioned to her that I would very much like to see more prints of the sutra. She searched her file once again, showed me a print in dark black ink, and gestured that it was the last piece she had. When I asked her how much it was, she indicated again that it was a gift to me. Overwhelmed, I bowed deeply once again.

That night I rested well in my tiny room in the ancient compound of Haein-sa, until the bells and drums started sounding at three o’clock in the morning, followed by chanting voices from the Avalokiteshvara Hall right next door.

Haein-sa means “monastery of ocean-mudra samadhi.” As described in the Avatamsaka Sutra, this samadhi represents a state of absorption in meditation like a calm ocean that reflects all beings and all teachings. One of the three major temples in Korea, this monastery, as the keeper of the Tripitaka woodblocks, represents the dharma treasure. It is the largest Buddhist training center in the country, with about two hundred resident monks. My visit to the monastery coincided with an interim period, so I saw only thirty or so monks, along with some lay workers in residence. (An American Zen teacher in a Korean Buddhist order later described this monastery as “the Oxford University of Korean Buddhism.”)

The next morning I saw Weonjo Sunim, a young attendant monk of the abbot and my host. I asked him if it would be possible for me to enter the sutra storehouse and take some pictures, to which he replied, “It’s not allowed to go inside, but I will show you the buildings.”

That afternoon, we climbed up the steep granite stairs in the back of the Buddha Hall. I told him that I was doing research on the Heart Sutra.

He smiled and said, “Oh, the Heart Sutra is the most important sutra in Korea. Do you understand the sutra?”

“I hope so.”

“My teacher says if you understand the Heart Sutra, you understand the entire buddha dharma.”

Quickly recalling my previous statement, I said, “In that case I must say I don’t understand the Heart Sutra.” We laughed.

Right behind the flight of the stairs, there stood a wide building of plain wood with a slightly arched roof. Weonjo pointed to the sign above the front entrance, which read “Sutra Hall.” We went through the short hallway into a courtyard and entered the central altar room of the storehouse building — the Dharma Treasure Hall. A dozen laypeople were sitting inside. They noticed my monk friend in his gray robe and bowed to him. After he returned their bows, we made nine full prostrations to the golden image of Vairochana Buddha.

We then went out from the Sutra Hall for worship into the courtyard, sandwiched by the storehouses. Each storehouse is fifteen kan long and two kan wide. (One kan in Korean, or one ken in Japanese, is roughly ten feet.) On each end of the courtyard stands a building of a similar structure, two kan in length. These buildings have vertically latticed, glassless windows all the way around.

Weonjo took me to one of the windows, through which we could see black-lacquered printing slabs stacked sideways like books, showing their vertical ends with engraving of the categories, sutra titles, and fascicle numbers. There were ten levels of plain wooden shelves, supported by bare pillars standing on square stone bases on the earthen ground.

Weonjo and I went around the building to the end, where we could see the central walkways through the building. It is said that each step in the process of manufacturing these printing slabs alone — cutting the white birch wood to size, submerging it in seawater, boiling it in fresh water, and drying it in the shade — takes three years to complete. The slabs are then cut exactly to size and engraved on both sides, which takes a number of years, and are finished with a coat of black lacquer. Indeed, the production of these blocks took a total of sixteen years. They have survived wars, fires, weather, and insects. Only a few blocks were found missing in 1915, and they were replaced some years later.9

“We haven’t found a better way to store them,” Weonjo said. In fact, some years prior to my visit, the monastery had constructed a multimillion-dollar building with the latest facilities, but found it inadequate to store the national treasure. So they decided to keep the woodblocks in the old way and use the new building as a study hall.

In response to the story of my research on the Heart Sutra and my lifelong admiration of the Goryeo Tripitaka, Weonjo said, “You might like to have a piece of the sutra. I will bring it to your room at four o’clock this afternoon.”

I thanked him, assuming that he would bring me another print of the Heart Sutra. But instead he brought a copper replica of the printing block of the sutra, placed in a beautiful cardboard box and wrapped in cloth.

How marvelous!